Abstract

Background:

The majority of expected deaths occur in hospitals where optimal end-of-life care is not yet fully realised, as evidenced by recent reviews outlining experience of care. Better understanding what patients and their families consider to be the most important elements of inpatient end-of-life care is crucial to addressing this gap.

Aim and design:

This systematic review aimed to ascertain the five most important elements of inpatient end-of-life care as identified by patients with palliative care needs and their families.

Data sources:

Nine electronic databases from 1990 to 2014 were searched along with key internet search engines and handsearching of included article reference lists. Quality of included studies was appraised by two researchers.

Results:

Of 1859 articles, 8 met the inclusion criteria generating data from 1141 patients and 3117 families. Synthesis of the top five elements identified four common end-of-life care domains considered important to both patients and their families, namely, (1) effective communication and shared decision making, (2) expert care, (3) respectful and compassionate care and (4) trust and confidence in clinicians. The final domains differed with financial affairs being important to families, while an adequate environment for care and minimising burden both being important to patients.

Conclusion:

This review adds to what has been known for over two decades in relation to patient and family priorities for end-of-life care within the hospital setting. The challenge for health care services is to act on this evidence, reconfigure care systems accordingly and ensure universal access to optimal end-of-life care within hospitals.

Keywords: Palliative care, hospital, terminal care, consumer participation, satisfaction

What is already known about the topic?

The majority of expected deaths, across the developed world, are within the hospital setting.

Optimal end-of-life care is not available for all who die in the hospital setting as evidenced by recent reviews outlining patient and family experience of end-of-life care.

What this paper adds?

An outline of what patients and family members from the developed world state is most important for end-of-life care in the hospital setting.

Data to inform policy makers and health care professionals when considering models of care for people with palliative care needs within the hospital setting.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

The development and implementation of models of end-of-life care for the hospital setting should be based within data outlining what is most important for patients with palliative care needs and their families.

The message from patients and families has remained consistent for over two decades with the challenge now being how to successfully deliver this care within the hospital setting.

Introduction

Most people state their preferred place of death is at home;1 however, the majority of deaths in the developed world occur in hospitals.2,3 In this review, ‘hospital’ refers to all acute inpatient care excluding psychiatric, hospice or inpatient specialist palliative care, and alcohol and drug treatment centres. In addition to the large number of known hospital palliative care deaths, it is estimated that at any given time almost a quarter (23%–24%) of all hospitalised patients have palliative care needs.4,5 Despite positive policy initiatives emphasising options to better support people to die at home,6,7 and an indication that advances in palliative care provision are enabling more people to die in the setting of their choice,8,9 the number of people requiring inpatient palliative care is expected to increase primarily due to the population ageing, increased burden and complexity of chronic illness, more people living in single person households and care needs exceeding community resources. Across the developed world, providing optimal end-of-life care for patients dying in our acute hospitals continues to be a priority.3,10,11

Despite the high proportion of expected hospital deaths, not all inpatients dying in this setting receive best evidence-based palliative care.12–14 The focus on cure and dominance of the biomedical model15,16 within hospitals makes it difficult to provide person-centred, holistic care that is grounded in comfort and dignity.12,14,17 Within the biomedical model, a dying patient is often viewed as a ‘failure’,17 which inadvertently prevents honest communication between clinicians and patients and/or families, leaves families feeling helpless and leads to unnecessary suffering as a result of patients receiving futile medical treatments and/or poor symptom management.18 While there is no uniform understanding or definition of what constitutes a ‘good death’,19 patients and families across the developed world have identified maintaining control, good symptom management, an opportunity for closure, affirmation of the dying person, recognition of and preparation for impending death and not being a burden as being crucial.19–21 Better understanding inpatients’ and families’ experience and/or satisfaction with end-of-life care in the hospital setting is vital for identifying targeted areas for improvement.22 However, identifying the most important elements of care, specifically from the perspectives of patients and families, is crucial to optimising hospital end-of-life care and guiding service development and/or redesign.

Aim

This systematic review aims to identify the five elements of end-of-life care that quantitative studies suggest are most important to hospitalised patients with palliative care needs and their families.

Method

The searches for this systematic review were undertaken during the first quarter of 2014 and focused on ‘importance’ and/or what elements of care that patients and/or families (next-of-kin, significant others, surrogates and/or informal caregivers) perceive enhance their satisfaction with and/or experience of hospital end-of-life care. For the purposes of this review, ‘experience’ was defined as an outline or description of an event or occurrence; ‘satisfaction’, as a measure of fulfilment in relation to expectations or needs and ‘importance’, as being of great significance or value.23

Eligibility criteria

Quantitative studies generating primary data were included if published in an English peer-reviewed journal between 1990 and 2014. The decision to limit inclusion to quantitative studies was taken to enable ranking of importance. Papers were included if they reported empirical patient and/or family data articulating ‘importance’ in relation to end-of-life care in hospital or satisfaction data that were statistically analysed to denote relative importance through identifying which components of care affected higher satisfaction levels. Papers were excluded if they were qualitative, did not provide primary data from patients or family members, were not in English, provided outcome measures that did not focus on the concept of importance, provided little or no focus on end-of-life care in the hospital setting, described experience and/or satisfaction only (without providing data to inform understanding of the care elements related to this), reported on a primary data set already included without relevant new perspectives provided or received a quality rating of 2 or less for ‘relevance to question’, with this being one of a suite of measures developed for appraising evidence for palliative care guidelines in Australia.24

Search

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and key words (Table 1) were developed (C.V. and J.P.) with support from a health service librarian and informed by key terms from known publications in this area. A search of relevant electronic databases was performed in March 2014, with slight variances made to these terms to account for different database requirements.

Table 1.

Search terms used.

| 1. dying, death, ‘end of life’, terminal, ‘terminal care’, terminally ill, palliative, ‘final day*’ (combine with ‘or’) |

| 2. ‘good death’, ‘consumer satisfaction’, ‘patient satisfaction’, perspective*, important, experience (combine all with ‘or’) |

| 3. Hospital, acute care, intensive care, emergency, inpatient* (combine all with ‘or’) |

| 4. Patient*, family, families, consumer*, carer* (combine all with ‘or’) |

| 5. Adult* |

| 6. Qualitative or quantitative |

| 7. 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and 5 and 6 |

| 8. Limit ‘7’ with 1990 – current and English language |

Slight variations with truncations were used to account for database requirements.

Information sources

Databases included the following: Academic Search Complete (EBSCO), AMED (OVID), CINAHL (EBSCO), MEDLINE (EBSCO), MEDLINE (OVID), EMBASE (OVID), PsycINFO (OVID), PubMed and Cochrane. Desktop searching of the internet via Google and Google Scholar search engines, CareSearch and handsearching was also completed. The reference lists of all included studies and other relevant reviews were searched manually to identify other potentially relevant papers.

Study selection

Articles returned from the electronic database searches were imported into Endnote (version X5), and the titles and abstracts of all papers examined (C.V.) to ascertain whether they met the inclusion criteria.

Data collection and items

Data were extracted into an electronic proforma in Microsoft Word. Items included the country in which the study was conducted, level of evidence, aim, design and method, participants and setting, outcome measures, results and care elements highlighted as important (Table 3). Two articles25,26 reporting on different aspects of the same data set were included because one25 reported on the whole data set, while the other reported on importance from the perspective of patients with cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).26

Table 3.

Extraction of data from included studies.

| Source, country | Aim | Design and method | Participants and setting | Outcome measures | Results/top five elements of importance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osborn et al.,28 USA | To identify areas requiring improvement in end-of-life care in the ICU | Descriptive design Surveys posted to caregivers 4–6 weeks post bereavement. Data analysis was performed to describe associations between two tools so a performance-importance grid evolved providing data about the areas of high importance and low satisfaction |

15 hospitals with an ICU. All caregivers who had a loved one die within an ICU (or within 30 h of transfer out of an ICU) between August 2003 and February 2008 | Family Satisfaction in the ICU (FS-ICU) and the single-item Quality of Dying (QOD-1) questionnaires | RR of 45%, n = 1290. 79 incomplete data sets therefore total for analysis: n = 1211 The five areas ranked as of highest importance were as follows: 1. Level of control over the care of the family member (1/24) 2. How well the nurses cared for the family member (2/24) 3. How well the ICU staff treated the family member’s pain (3/24) 4. Feeling supported in the decision making process (4/24) 4. The courtesy, respect, and compassion the family member was given (4/24) (Both items ranked equally as 4/24) 5. How well the ICU staff treated the family member’s agitation (5/24) High QOD-1 scores significantly (p < 0.05) associated with perceived nursing skill and competence; support for family as decision makers; family control over the patient’s care; ICU atmosphere Three areas noted as highly important but with low satisfaction scores: 1. Atmosphere of the ICU (p = 0.03) 2. Level of support given for decision making (p = 0.03) 3. Amount of control over care (p ⩽ 0.01) |

| Heyland et al.,35 Canada | To identify key areas of end-of-life care requiring improvement from the perspectives of patients and families | Descriptive design Face-to-face survey using a validated tool. This tool is the result of several studies including those reported below. Statistical analysis to derive relative importance of elements conducted through association with the global rating of satisfaction |

Inpatient, outpatient and home care clients from a large region of Canada, (inpatient data only provided here). Older patients with advanced disease with an estimated prognosis of 6 months or less, and their caregivers. |

CANHELP questionnaire (www.thecarenet.ca) | RR for hospital patients: 54%, n = 256 (77% RR for all care settings) RR for hospital family caregivers: 45%, n = 114 (76% RR for all care settings) The top five elements noted as important for patients include the following: 1. Doctors and nurses preserve patient dignity (1/37); 2. Good care when family/friend not present (2/37); 3. Appropriate tests and treatments used for medical treatment (3/37); 3. Health care workers work as a team (3/37); 3. Doctors and nurses compassionate and supportive (3/37); 4. Well informed doctors and nurses about the patient’s health problems to give you the best possible care? (4/37); 5. Adequate environment for care (5/37); 5. Physical symptoms adequately assessed and controlled? (5/37) (Those noted as 3 above had equal data ratings) The top five elements noted as important for family caregivers include the following: 1. Trust and confidence in doctors (1/38); 2. Availability of doctors (2/38); 3. Doctors and nurses compassionate and supportive to family caregiver (3/38); 4. Doctors and nurses compassionate and supportive to patient (4/38); 5. Doctors take a personal interest in patient (5/38). |

| Young et al.,34 UK | To explore the determinants of satisfaction with care at the end-of-life for people dying following a stroke in hospital | Descriptive design Postal survey of bereaved relatives followed by exploratory analyses to identify determinants of satisfaction |

Random sample of informants who had registered a stroke death across four Primary Care Trusts in London (2003) | Survey tool adapted from the Views of Informal Carers Evaluation of Services (VOICES) questionnaire. The stroke-specific version was adapted following a literature review, interviews with 21 professionals and 6 bereaved carers. This study focuses on data from the domains: last hospital admission and care in the last 3 days of life |

N = 183 (RR = 37%) with n = 126 (76%) died in a hospital setting. Data related to this setting and related to satisfaction determinants only are reported here. High satisfaction with hospital doctors and nurses predicted by the following: able to discuss worries and fears with hospital staff about deceased condition, treatment or tests (p = 0.004); doctors and nurses knew enough about deceased’s condition (p < 0.001) and role of carer (spouse/partner V other) (p = 0.049) High satisfaction with health and social services in the last 3 days of life predicted by: Enough help available to help with personal care needs (<0.001); Involved in decisions about the deceased treatment and care (p = 0.006); Felt the deceased died in the right place (p = 0.041) Rankings for the top five areas of importance: 1. Doctors and nurses knew enough about the deceased’s condition (focus on doctor) (1/7); 2. Enough help available to help with personal care needs (2/7); 3. Doctors and nurses knew enough about the deceased’s condition (focus on nurse) (3/7); 4. Able to discuss worries and fears with hospital staff about deceased condition, treatment or tests (focus on doctor) (4/7); 5. Felt that the deceased died in the right place (5/7); |

| Rocker et al.,26 Canada NB: This study reports on data used within the Heyland 2006 study (reported below) |

Describe key elements of end-of-life care and the relative importance of these from the perspective of people with advanced COPD as compared to people with cancer. | Descriptive design Face-to-face questionnaire starting with an open-ended question and followed by the provision of 28 elements for rating. Comparative statistics used to determine differences/similarities between patients with COPD and cancer in relation to rated elements of importance. |

Five teaching hospitals. Older patients with advanced COPD with an estimated prognosis of 6 months or less. | Survey tool developed following literature review, expert opinion and focus groups with patients, enabling a tool with 28 elements of care organised into five domains. | Patients = 118 (COPD) and 166 (cancer) Top five elements rated ‘extremely important’: 1. Not to be kept alive on life support when there is little hope for a meaningful recovery (COPD: 55%; Ca: 58%); 2. Symptom relief (COPD: 47%; Ca: 37%) 3. Adequate plan of care and availability of home care resources (COPD: 40%; Ca: 44%) 4. Trust and confidence in doctors (COPD: 40%; Ca: 65%) p < 0.01 5. Not to be a physical or emotional burden on family (COPD: 40%; Ca: 47%) |

| Heyland et al.,25 Canada NB: This study uses the same data set as reported above by Rocker et al.26 |

Describe key elements of end-of-life care and the relative importance of these from a patient and caregiver perspective. | Descriptive design Face-to-face questionnaire starting with an open-ended question and followed by the provision of 28 elements for rating. Caregiver and family questionnaires identical in content. |

Five teaching hospitals. Older patients with advanced disease with an estimated prognosis of 6 months or less, and their caregivers. | Survey tool developed following literature review, expert opinion and focus groups with patients, enabling a tool with 28 elements of care organised into five domains. | RR = 77%; Patients n = 440; Caregivers n = 160 The top five elements noted as important for patients include the following: 1. To have trust and confidence in the doctors looking after you (1/28); 2. Not to be kept alive on life support when there is little hope for a meaningful recovery (2/28); 3. That information about your disease be communicated to you by your doctor in an honest manner (3/28); 4. To complete things and prepare for life’s end (life review, resolving conflicts, saying goodbye) (4/28); 5. To not be a physical or emotional burden on your family (5/28); 5. Upon discharge from hospital, to have an adequate plan of care and health services available to look after you at home (5/28); |

| The top five elements noted as important for family caregivers include the following: 1. To have trust and confidence in the doctor looking after the patient (1/25); 2. To not have your family member be kept alive on life support when there is little hope for a meaningful recovery (2/25); 3. That information about your family member’s disease be communicated to you by the doctor in an honest manner (3/25); 4. To have an adequate plan of care and health services available to look after him or her at home, after discharge from hospital (4/25); 5. That your family member has relief of physical symptoms such as pain, shortness of breath and nausea (5/25); |

|||||

| Baker et al.,32 USA | To examine factors affecting family satisfaction with end-of-life care in the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT) | Descriptive design Initial prospective cohort study with patients randomised to usual care or intervention. Intervention included access to palliative care clinical nurse specialists. This study reports on after death interviews conducted by telephone 4–10 weeks after patient death. Descriptive and statistical analysis used to convey data and look for relationships between scores |

Five teaching hospitals. Caregivers for seriously ill, hospitalised adults who died from an expected death at least 48 h after admission between February 1993 and January 1994. | After-death interview consisting of eight items adapted from previous studies of satisfaction with terminal care. Satisfaction measures focused on two areas: patient comfort and communication/decision making | RR of 78% (n = 767) Satisfaction with patient comfort decreased as financial impacts increased (p < 0.5) Satisfaction with patient comfort greater when family preferences for care were followed (p < 0.0001) Satisfaction with communication and decision making was significantly higher when patient died on that admission (p = 0.05) |

| Steinhauser et al.,21 USA | To determine the factors considered important at the end-of-life by patients, their families, physicians and other care providers Only patient and family data summarised here |

Descriptive design. Cross-sectional, stratified random national survey (March–August 1999) |

Seriously ill patients randomly selected from the national Veteran Affairs database (using disease classification codes to account for advanced chronic illness) and recently bereaved family selected from the same database in relation to patients who had died 6 months–1 year earlier. | Survey tool of 44 attributes generated from 12 previously conducted focus groups and in-depth interviews with patients, family members and health care professionals who were asked to define attributes of a good death. | RR: patients 77% (n = 340); family members 71% (n = 332) The top five attributes (out of 44) rated as important by patients and/or families include the following: Patient rankings of importance: 1. Be kept clean (1/44) 2. Name a decision maker (2/44) 3. Have a nurse with whom one feels comfortable (3/44) 4. Know what to expect about one’s physical condition (4/44) 5. Have someone who will listen (5/44) 5. Maintain one’s dignity (5/44) (elements noted as 5 received same ranking) Family rankings of importance: 1. Be kept clean (1/44) 2. Name a decision maker (2/44) 2. Maintain one’s dignity (2/44) 2. Have a nurse with whom one feels comfortable (2/44) 2. Have someone who will listen (2/44) 3. Trust one’s physician (3/44) 4. Be free of pain (4/44) 4. Presence of family (4/44) 5. Have physical touch (5/44) 5. Have financial affairs in order (5/44) (Where rankings are repeated they were ranked equally within study) |

| Kristjanson,33 Canada NB: Article retrieved via handsearching as original date range searched = 1990–2014 |

To identify health care professional behaviours that are important to patients and their caregivers and identify whether care settings influence these perceptions. | Descriptive design. Q-sort methodology used to identify most important elements of care that were informed from a previous qualitative study. These elements were separated into patient care and family care with caregivers sorting one group only. Cards ranked from most important to least important. This study looked at Hospice, home care and acute care settings. Acute care data only are reported here. |

Convenience sample of 210 caregivers of patients with advanced cancer, from three wards within a tertiary hospital. 108 caregivers sorted cards for patient care and 102 sorted for family care | Importance of key elements of care developed via a phase 1 qualitative study | Patient care items, acute care – the following five are most important: 1. Physician assesses symptoms thoroughly 2. Symptoms treated quickly 3. MD pays attention to patient’s description of symptoms 4. Pain relieved quickly 5. Tests and treatments followed up Family care items, acute care – five most important: 1. Information about patient’s prognosis 2. Caregivers straightforward when answering questions 3. Information on side effects 4. Information on future stages of treatment and care 5. Family conference arranged by MD to discuss patient’s illness |

ICU: intensive care unit; CANHELP: Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project; RR: response rate; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Bias rating

Quality appraisal of potential studies was completed independently by two researchers (C.V. and T.L.) using the Australian Palliative Residential Aged Care (APRAC) Guidelines for a Palliative Approach in Residential Aged Care: Evidence evaluation tool for quantitative studies (Table 2),24 and this guided decisions about the final studies for inclusion. The quality indicator of ‘relevance to the research question’ was used to limit inclusion. The level of evidence generated by each study was classified according to the (Australian) National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).27

Table 2.

Quality rating of included articles.

| Article | Osborn et al.28 | Gelfman et al.29 exclude | Moyano et al.30 exclude | Heyland et al.25 | Heyland et al.31a | Baker et al.32 | Kristjanson33 | Young et al.34 | Rocker et al.26 | Heyland et al.35 | Steinhauser et al.21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aim | To inform areas for quality improvement interventions in the ICU in relation to end-of-life care | To assess quality of medical care at the end-of-life in hospital | To evaluate satisfaction levels of caregivers in relation to information provision at the end-of-life in hospital | To describe key elements of end-of-life care and the relative importance of these from a patient and caregiver perspective | To increase understanding about what high-quality end-of-life care in a hospital setting means from a patient and family perspective and how satisfied with these elements of care they are | To examine factors affecting family satisfaction with end-of-life care in the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT) | To identify health care professional behaviours that are important to patients and their caregivers and identify whether care settings influence these perceptions | To explore the determinants of satisfaction with care at the end-of-life for people dying following a stroke in hospital | Describe key elements of end-of-life care and the relative importance of these from the perspective of people with advanced COPD as compared to people with cancer | To identify key areas of end-of-life care requiring improvement from the perspectives of patients and families | To determine the factors considered important and the end of life by patients, their families, physicians, and other care providers |

| Design | Descriptive | Descriptive | Descriptive | Descriptive | Descriptive | Descriptive | Descriptive | Descriptive | Descriptive | Descriptive | Descriptive |

| Level (as per NHMRC) | IV | IV | IV | IV | IV | IV | IV | IV | IV | IV | IV |

| Quality of methods | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Relevance to questionb | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Evaluator(s) | C.V./T.L. | C.V./T.L. | C.V./T.L. | C.V./T.L. | C.V./T.L. | C.V./T.L. | C.V./T.L. | C.V./T.L. | C.V./T.L. | C.V./T.L. | C.V./T.L. |

ICU: intensive care unit; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NHMRC: National Health and Medical Research Council.

Excluded due to the fact this study reported on the same data set as Heyland et al.25 without new perspectives provided.

Any studies rated as ⩽2 for this measure were excluded.

Synthesis

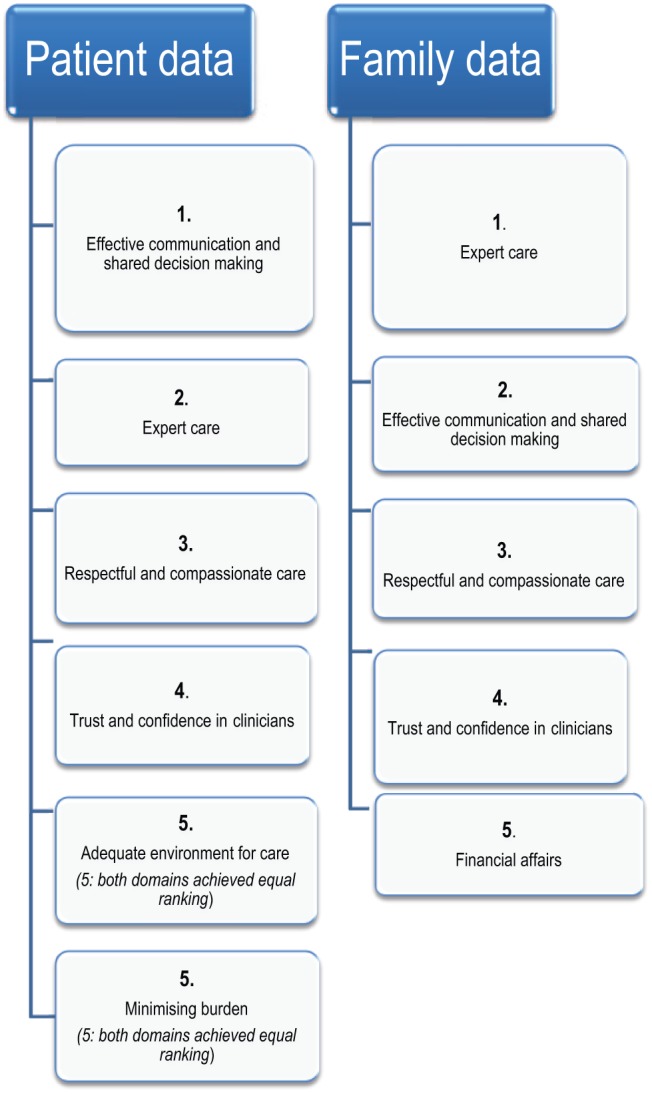

A narrative approach to synthesis allowed for the integration of the broad range of designs and methods within the included studies. The synthesis followed the methods recommended by Popay et al.,36 notably tabulation and content analysis (Table 3). Content analysis occurred through the organisation of data into care domains or overarching categories. Elements of care ranked as the top five most important in each article were tabulated, analysed and grouped into domains (Tables 4 and 5). The initial domains were compiled (C.V.) before being reviewed by the team. Where there was a difference in opinion, discussion was held to reach consensus. The frequency of each domain was summarised as an index of overall priority from a patient and family perspective (Figure 2). Where data were shared across articles,25,26 the frequency count was only calculated once.25

Table 4.

Representation of the top five ranked elements of end-of-life care in the hospital setting from the perspectives of patients.

| Study | Domains |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effective communication and shared decision making | Expert care | Respectful and compassionate care | Trust and confidence in clinicians | Adequate environment | Minimising burden | |

| Heyland et al.35 | With the tests that were done and the treatments that were given during the past month for your medical problems? (3/37)a | That during the past month, you received good care when a family member or friend was not able to be with you? (2/37)a

That health care workers worked together as a team to look after you during the past month? (3/37)a That the doctors and nurses who looked after you during the past month knew enough about your health problems to give you the best possible care? (4/37)a That physical symptoms you had during the past month (e.g. pain, shortness of breath and nausea) were adequately assessed and controlled? (5/37)a |

That you were treated by the doctors and nurses in a manner that preserved your sense of dignity during the past month? (1/37)a

That the doctors and nurses looking after you during the past month were compassionate and supportive? (3/37)a |

Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study | With the environment or the surroundings in which you were cared for during the past month? (5/37)a | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study |

| Rocker et al.26b | Not to be kept alive on life support when there is little hope for a meaningful recovery (COPD: 1/28; Cancer: 2/28)a | To have relief of symptoms, that is, pain, shortness of breath, nausea and so on (COPD: 2/28; Cancer: 12/28)a

To have an adequate plan of care and health services available to look after you at home upon discharge from hospital (COPD: 3/28; Cancer: 6/28)a |

Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study | To have trust and confidence in the doctors looking after you (COPD: 4/28; Cancer: 1/28)a | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study | That you not be a physical or emotional burden on your family (COPD: 5/28; Cancer: 5/28)a |

| Heyland et al.25 | Not to be kept alive on life support when there is little hope for a meaningful recovery (2/28)a

That information about your disease be communicated to you by your doctor in an honest manner (3/28)a To complete things and prepare for life’s end (life review, resolving conflicts and saying goodbye) (4/28)a |

Upon discharge from hospital, to have an adequate plan of care and health services available to look after you at home (5/28)a | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study | To have trust and confidence in the doctors looking after you (1/28)a | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study | To not be a physical or emotional burden on your family (5/28)a |

| Steinhauser et al.21 | Name a decision maker (2/44)a

Know what to expect about one’s physical condition (4/44)a Have someone who will listen (5/44)a |

Be kept clean (1/44)a | Maintain one’s dignity (5/44)a | Have a nurse with whom one feels comfortable (3/44)a | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study |

| Frequency | 7 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Domains: overarching categories developed by this review through data synthesis; Domain name in italics: domain that is specific to patient data (not found in top rankings of family data); Data in each cell: primary data from each article ranked in their top five elements of care; Frequency: overall frequency count for data within each domain collated by this review; Shaded cells: domain not ranked in the top 5 rankings for this particular study.

Numerical data in brackets are the ranking of all elements of care measured in each article.

Same primary data used and therefore frequency count uses major data set only.25

Table 5.

Representation of the top 5 ranked elements of end-of-life care in the hospital setting from the perspectives of families.

| Study | Domain |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert care | Effective communication and shared decision making | Respectful and compassionate care | Trust and confidence in clinicians | Financial affairs | |

| Osborn et al.28a | How well the nurses cared for your family member (2/24)b

How well the ICU staff treated your family member’s pain (3/24)b How well the ICU staff treated your family member’s agitation (5/24)b |

Did you feel you had control over the care of your family member? (1/24)b

Did you feel supported in the decision making process? (4/24)b |

The courtesy, respect, and compassion your family member was given (4/24)b | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study |

| Heyland et al.35 | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study | That the doctor(s) were available when you or your relative needed them (by phone or in person) during the past month? (2/38)b | That the doctors and nurses looking after your relative during the past month were compassionate and supportive of you? (3/38)b

That the doctors and nurses looking after your relative during the past month were compassionate and supportive of him or her? (4/38)b That the doctor(s) took a personal interest in your relative during the past month? (5/38)b |

With the level of trust and confidence you had in the doctor(s) who looked after your relative during the past month? (1/38)b | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study |

| Young et al.34 | Doctors and nurses knew enough about the deceased’s condition (focus on doctor)(1/7)b

Enough help available to help with personal care needs (2/7)b Doctors and nurses knew enough about the deceased’s condition (focus on nurse) (3/7)b Felt that the deceased died in the right place (5/7)b |

Able to discuss worries and fears with hospital staff about deceased condition, treatment or tests (focus on doctor) (4/7)b | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study |

| Heyland et al.25 | To have an adequate plan of care and health services available to look after him or her at home, after discharge from hospital (4/25)b

That your family member has relief of physical symptoms such as pain, shortness of breath and nausea (5/25)b |

To not have your family member be kept alive on life support when there is little hope for a meaningful recovery (2/25)b

That information about your family member’s disease be communicated to you by the doctor in an honest manner (3/25)b |

Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study | To have trust and confidence in the doctor looking after the patient (1/25)b | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study |

| Baker et al.32c | Comfort score was inversely associated with the degree of patient pain during the last 3 days of life | Surrogates who reported patient’s preferences were followed moderately or not at all had less satisfaction | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study | Surrogates who reported the patient’s illness had greater effect on family finances had less satisfaction |

| Steinhauser et al.21 | Be kept clean (1/44)b

Be free of pain (4/44)b |

Name a decision maker (2/44)b

Have someone who will listen (2/44)b |

Maintain one’s dignity (2/44)b

Presence of family (4/44)b Have physical touch (5/44)b |

Have a nurse with whom one feels comfortable (2/44)b

Trust one’s physician (3/44)b |

Have financial affairs in order (5/44)b |

| Kristjanson33d |

Important for patients: Physician assesses symptoms thoroughly (1/74)b

Symptoms treated quickly (2/74)b MD pays attention to patient’s description of symptoms (3/74)b Pain relieved quickly (4/74)b |

Important for patients: Tests and treatments are followed up (5/74)b

Important for families: Information provided about patient’s prognosis (1/77)b Caregivers are straightforward when answering questions (2/77)b Information provided about side effects of treatments and drugs (3/77)b Information on future stages of treatment and care (4/77)b Family conference arranged by MD to discuss patient’s illness (5/77)b |

Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study | Domain not rated in top five elements of care in this study |

| Frequency | 16 | 15 | 7 | 4 | 2 |

ICU: intensive care unit.

Domains: overarching categories developed by this review through data synthesis; Domain name in italics: domain that is specific to family data (not found in top rankings of patient data); Data in each cell: primary data from each article ranked in their top five elements of care; Frequency: overall frequency count for data within each domain collated by this review; Shaded cells: domain not ranked in the top five rankings for each particular study.

This study had one element of care that was not categorised due to insufficient information as disclosed by the authors. This element was ‘the atmosphere of ICU (3/24)b’ with it being unclear whether this referred to the physical environment, policies regarding visitation or staff efforts to enable family comfort.

Numerical data in brackets is the ranking of all elements of care measured in each article.

Data not formally ranked – statistically significant scores included here.

Study asks participants to rank important elements for patient care and family care. Both sets of ranked data were provided (noted as patient or family focus) and both counted in overall frequency.

Figure 2.

Rankings determined by frequency of representation of domains in top 5 categories of rated importance for patients and families. The domains of adequate environment for care and minimising burden were unique to patient data. The domain of financial affairs was unique to the family data.

Results

Study selection

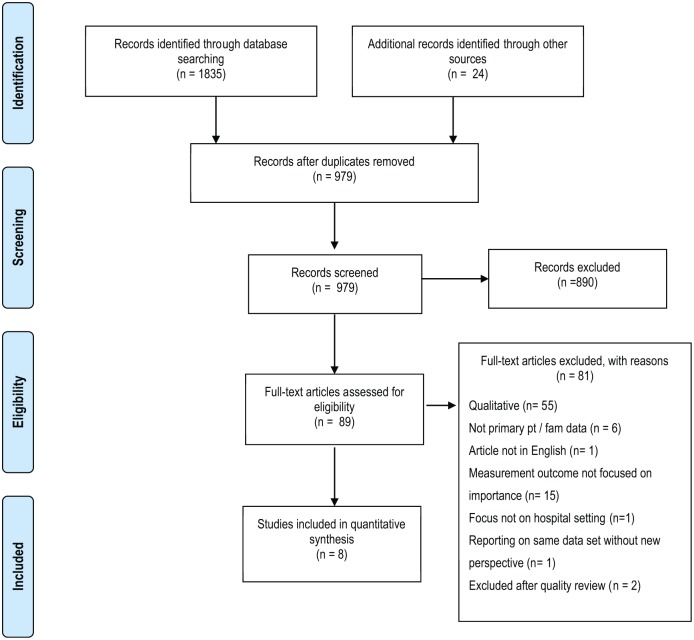

Of 1859 articles returned by searches, 8 were assessed as meeting inclusion criteria (see Figure 1). An outline of the quality review of all articles is provided in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Processing of information from identification to inclusion in this systematic review.

Study characteristics

Study location

The included studies came from three developed countries in the northern hemisphere: Canada (n = 4),25,26,33,35 United States (n = 3)21,28,32 and the United Kingdom (n = 1) (Table 3).34

Study design

The majority of studies (n = 6) employed descriptive designs, using mostly postal or face-to-face surveys.21,25,26,28,34,35 One study used a prospective cohort study design comparing usual care with an intervention where additional support was provided by a Clinical Nurse Specialist.32 However, the data relevant to this review were retrospective and cross-sectional survey data. The other study used a Q-sort methodology where participants ranked elements of importance identified by a previous qualitative study.33 All were classified as Level IV studies according to the NHMRC classification system, indicating a lower level of evidence in line with descriptive design use only.27

Sample characteristics

Seven studies included family21,25,28,32–35 with three of these also including patients.21,25,35 One study included patients only,26 with the sample drawn from a larger previously reported study.25 The views from 1141 patients and 3117 families are captured in this review. Studies reporting patient data come from two research centres21,25,35 in two countries, Canada and the United States. Four papers21,25,28,35 that reported a mean age show their patient cohorts had a mean age of approximately 71.5 years (standard deviation (SD) ± 3.88) and two papers that provide age ranges had cohorts >70 years (86%)34 and >50 years (87%).33 All studies had equal representation of males and females. The majority of patients (⩾70%) had no post school qualifications, with the proportion of White participants ranging from 69% in one study21 to ⩾87% across all other studies.21,25,26,35 Family members tended to be younger than patients and included ⩾65% of females except in one study where there was gender equity (52%).34 Families had mixed education levels but higher levels of education compared to the patient sample and were predominantly a spouse or adult child and White on ⩾76% of occasions.21,25,28,32–35 Four studies surveyed bereaved relatives.21,28,32,34

Synthesis

Patient data on elements of importance were synthesised into six domains and family data into five domains (Figure 2). Four domains were in common across patient and family reports: (1) effective communication and shared decision making, (2) expert care, (3) respectful and compassionate care and (4) trust and confidence in clinicians. There were two additional domains that patients ranked as being equally important: (1) adequate environment for care and (2) minimising burden. Families noted one additional domain: financial affairs. The frequency of ranked elements of care within the four common domains was very similar across the patient and family sample (Figure 2). Effective communication and shared decision making and expert care were noted ⩾50% more often than other domains by all samples, suggesting these two domains may be of highest importance for both patients and families (Tables 4 and 5). The key care strategies that patients and families identified as part of the most important elements of hospital end-of-life care are summarised below.

Effective communication and shared decision making

Across all included studies, effective communication and shared decision making were noted as highly important – the only domain for which this was the case. For patients, honest communication, the ability to prepare for life’s end,25 ensuring availability of someone to listen and being aware of what to expect about their physical condition21 were considered to be especially important elements of care at the end-of-life. In relation to shared decision making, patients specifically noted the importance of appropriate tests and treatments,35 not being placed on life support when there was little hope for recovery25,26 and having an opportunity to nominate their preferred decision maker.21

In addition to the elements of care noted by patients above, families also identified the availability of medical staff to talk to as required35 and the opportunity to participate in a family conference to review the patient’s illness as being highly important.33 Similarly to patients, families also ranked the need for honest communication as one of the most important elements of end-of-life care in hospital, and being sheltered from the reality of the situation as one of the least important aspects of care.33 Furthermore, families noted the importance of feeling supported in decision making and having a sense of control over their loved one’s care,28 with one study showing a statistically significant linkage between satisfaction and family reporting that patient preferences were followed.32 In addition, the value of being able to speak with medical staff about a loved one’s condition, treatment and tests34 and to receive straightforward information about prognosis, tests, treatments and future options for care33 were all ranked as highly important by families.

Expert care

Expert care was noted across all studies providing patient data (Table 4) and six out of the seven studies reporting family data (Table 5). This domain includes three main concepts for care including (1) good physical care, (2) symptom management and (3) integrated care.

Good physical care was noted by patients and families as the most important element of care in one study,21 specifically noting this as ‘being kept clean’. Families also stated this in relation to personal care needs34 and the importance of how well nurses cared for their loved one.28 Finally, patients noted the importance of receiving good care when family members were not present.35

Patients ranked the importance of symptom relief in the top five ranked elements of care in a recent Canadian study,35 having not ranked this in the top five elements prior to this time. Family specifically noted management of pain and agitation to be highly important21,28,32,33 as well as noting the importance of rapid and thorough assessment and treatment with a focus on the patient’s description of their symptoms.33

The importance of integrated care was noted by both patients and families specifically in relation to effective discharge planning25,26 and by family in ensuring the deceased died in the right place.34 Furthermore, the importance of clinicians being knowledgeable about the specific condition of the patient was noted by both patients and families.34,35 Finally, patients noted the importance of clinicians working together as a team in relation to their care.35

Respectful and compassionate care

Respectful and compassionate care was noted as highly important for both patients and families and has been so since 2000.21 As respectful care ought to ensure the preservation of dignity, these elements of care were considered to fall into the ‘respectful and compassionate care’ domain identified in our synthesis (Tables 4 and 5). The preservation of dignity was noted by patients as extremely important in two separate studies conducted over a decade apart.21,35 Indeed, the more recent study noted the preservation of dignity as the most important element of care.35 In addition to this, patients noted the importance of clinicians being compassionate and supportive,35 and this was echoed by family in relation to the care of the patient and also themselves.28,35 Families also noted the importance of doctors taking a personal interest in their loved one35 as well as the presence of family, the ability to have physical touch and again, the maintenance of dignity.21

Trust and confidence in clinicians

Similar to the domain of respectful and compassionate care, trust and confidence in clinicians was noted as important to both patients and families and has been so across several studies since 2000.21,25,26,35 When analysed by diagnosis, this element of care was found to be more important for patients with cancer (65%, n = 166) than for patients with COPD (40%, n = 118) with this difference found to be statistically significant (p < 0.01).26

Adequate environment for care – domain ranked by patients only

In a recent Canadian study, patients noted the importance of an adequate environment of care (Table 4).35 However, this is in contrast to earlier data outlining that only 16% of patients (ranked 25 out of 28) and 37% of families (ranked 18 out of 28) rated this as extremely important.25 This concurs with earlier work by Kristjanson33 which outlined that two of the five least important aspects of care for patients were having a large hospital room with personal effects allowed from home. Nevertheless, an adequate environment of care was evident on one occasion for patients within this review (Table 4).

Families did note the importance of the ‘atmosphere of an ICU’ with this correlating with a low satisfaction score (p = 0.03).28 However, as noted by the authors,28 the exact nature of what was meant by this statement is unclear, and therefore, this element of care was not included within any specific domain for families (Table 5, noted in the key).

Minimising burden – domain ranked by patients only

Ensuring one is not a physical or emotional burden was ranked as highly important by patients in Heyland’s study25 with these results remaining consistent when analysed by patient diagnosis (COPD/Cancer).26 This aspect of care was not specifically questioned in the family data set for the Heyland study.25

Financial affairs – domain ranked by families only

Two large US studies21,32 noted the importance of financial affairs in relation to end-of-life care. One study focused on the impact of a patient’s illness on finances with this significantly affecting family’s satisfaction with patient comfort (p < 0.05).32 Another US study showed that families ranked having financial affairs in order in their top five categories of importance in relation to end-of-life care (Table 5).21 While the Canadian studies25,35 included financial affairs on the ranking instrument, this element of care did not rank within the top five elements considered most important by family.

Discussion

This systematic review has revealed that effective communication, shared decision making and expert care, indicators of quality end-of-life care, are the domains of hospital end-of-life care that patients and families consider to be most important. Kristjanson33 over 25 years ago identified these same end-of-life care domains as being a priority for dying patients and their families. This review adds new insight into the need for respectful and compassionate care as well as trust and confidence in clinicians with these domains important to both patients and families. It also suggests that an adequate environment of care and ensuring burden of care is minimised is of unique importance to patients and ensuring financial affairs are in order, of unique importance to families. The financial data element was generated from US data but was not reflected in the data generated from countries with a universal health system. While a universal health care system may provide additional safety net and security for families when supporting people with palliative care needs, the reasons for carer financial strain are more complex. An Australian report found that carers of those with palliative care needs often experience financial strain as a result of needing to reduce their work hours or to leave paid work alongside increased out-of-pocket health care expenses.37 It is also identified that financial strain impacted adversely on carers’ health and wellbeing.37 Therefore, this claim requires further analysis prior to final conclusions and warrants attention to truly understand the needs of families in relation to financial matters.

There is evidence from a recent integrative review that patients and/or families perceive that the above-mentioned domains of care are often poorly addressed within the hospital setting,10 with symptom control and burden, communication with clinicians, decision making related to patient care and management, inadequate hospital environment and interpersonal relationships with clinicians all themes noted as areas required for ongoing focus and improvement.10 In addition to this, a recent large Canadian study38 found statistically significant unmet need for patients in relation to communication and being treated with respect (p < 0.0001) and for family members in relation to obtaining information (p < 0.001), knowing what to expect (p < 0.01) and coordination of care (p < 0.01). The considerable body of evidence about both what is important for patients with palliative care needs and their families and the fact that this is not currently always provided in hospitals reaffirms the importance of end-of-life care reform within this setting. These insights are not new with what patients and families considered to be most important having been identified more than a quarter of a century ago.

Yet, health care organisations have largely failed to develop systems that ensure these important elements of care are routinely provided to every patient dying in hospital. The challenge is for clinicians, health care systems and public policy to drive profound improvement in these areas. Given the lack of directed policy work specifically on end-of-life care in the hospital setting internationally, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care’s11 recent draft consultation document on essential elements for safe and high-quality end-of-life care in Australian acute hospitals is a positive public policy development. The 10 essential elements outlined by the Commission to enable optimal palliative care in the Australian hospital setting correlate strongly with the domains reported in this review. This consultation document identifies a need to move from a purely person-centred approach to care to end-of-life care that is underpinned by trust and confidence in clinicians, respectful and compassionate care, preservation of dignity and clinical expertise. The Commission calls for end-of-life care to be strengthened across all of these domains, building the capacity of the health workforce to deliver optimal end-of-life care as well as the development of explicit process and outcome measures to support implementation and sustain improvements.11

While the message is clear in relation to what patients and families need for optimal end-of-life care in the hospital setting, the challenge is to enable this within an environment focused on acute and episodic care. Over a decade ago, the World Health Organization proposed a model for innovative care for chronic conditions that challenges the health system to a new way of thinking and a new way of organising care with linkages at macro (policy), meso (health care organisation) and micro (community) levels required.39 Such systems ought to be applied to end-of-life care with a focus on the patient and family unit at the micro level.

A person-centred approach to care complemented by greater development of staff expertise in symptom management and effective communication, health care systems enabling coordinated care and a supportive policy environment that prioritises palliative care in the hospital system all contribute to important components of a model of care that will enable optimal care for patients at the end of their life, and their families, within the hospital setting. Developing and validating meaningful measures of service delivery based around such person-centred domains is vital to seeing future improvements in hospital end-of-life care. Given the large number of people dying in hospital settings across the world, developing and testing models of care to enable this remains an urgent priority.

Recommendations for future practice

There is a consistent message from patients and their families in the developed world, who are predominately White adults, in relation to what is important to them in terms of hospital end-of-life care. What remains elusive is how to enact change within the health care system to ensure universal access to care that is inclusive of all such domains of importance. Models of care designed around this information need to be implemented, tested and systematically measured to enable improvements for the longer term. Furthermore, this review found importance for families in relation to their financial affairs, and a greater understanding of this both in relation to needs and possible burdens is required.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this review lies in the systematic methodology used to limit bias, develop accurate and reliable conclusions and to assimilate large amounts of information to inform future health service development.40 Furthermore, the focus on patient and family data alone ensures this review reports their perspectives to inform future policy and health service design changes. However, there are also several limitations to this review. First, a single author examined the titles and abstracts and undertook data extraction for included studies. However, where uncertainty existed, discussion with the research team was undertaken for a consensus view. Second, only descriptive data were reported and therefore should be seen as informative rather than definitive. Additionally, the focus on purely quantitative data allows discrete categorical data only and additional depth through qualitative analysis is warranted. Third, the narrative approach to synthesis can include some subjectivity in relation to theming and interpretation of data, although again, group consensus was sought to minimise this risk. Fourth, the sample involved in this review is biased towards Western developed world culture, White adults, predominantly older patients and female family caregivers (adult children or spouses). While the patient perspective has been captured, not all studies universally reported patient data. Therefore, a major limitation of this review is that the perspective of the elements of end-of-life care considered to be important from diverse cultures within the developed world is not reported with the review sample biased towards older White adults from Northern America and female caregivers and with limited patient-reported data. There are several elements that fell outside of the top five most important elements of care in studies reporting more than five elements that warrant further exploration.

Conclusion

The message from patients with palliative care needs and their caregivers about what domains of care are most important at the end-of-life in the hospital setting has remained consistent for over two decades. These domains are as follows: effective communication and shared decision making with particular reference to limiting futile treatments and enabling preparation for the end-of-life; expert care at all times with particular reference to good physical care, symptom management and integrated care; respectful and compassionate care with particular reference to preservation of dignity; trust and confidence in clinicians; an adequate environment for care; minimising burden and the importance of financial affairs. Developing and evaluating models of care to enable these domains of care for all patients with palliative care needs and their families remains an urgent priority for health care services across the world.

Acknowledgments

All authors contributed to defining the search aims and methodology used for identification and analysis of all included data. C.V. conducted the focused search for this study. Study selection and quality rating were completed by C.V. and T.L. Data extraction was completed by C.V. and she was assisted by T.L. and J.P. in the synthesis. All authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. Billingham MJ, Billingham SJ. Congruence between preferred and actual place of death according to the presence of malignant or non-malignant disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013; 3: 144–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Broad JB, Gott M, Kim H, et al. Where do people die? An international comparison of the percentage of deaths occurring in hospital and residential aged care settings in 45 populations, using published and available statistics. Int J Public Health 2013; 58: 257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tang ST, Chen C-H. Place of death and end-of-life care. In: Cohen J, Deliens L. (eds) A public health perspective on end of life care. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- 4. To T, Greene A, Agar M, et al. A point prevalence survey of hospital inpatients to define the proportion with palliation as the primary goal of care and the need for specialist palliative care. Intern Med J 2011; 41: 430–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gott CM, Ahmedzai SH, Wood C. How many inpatients at an acute hospital have palliative care needs? Comparing the perspectives of medical and nursing staff. Palliat Med 2001; 15: 451–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Commonwealth of Australia. Supporting Australians to live well at the end of life. Canberra, ACT, Australia: National Palliative Care Strategy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Department of Health. End of life care strategy: promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. London: Department of Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gomes B, Calanzani N, Higginson IJ. Reversal of the British trends in place of death: time series analysis 2004–2010. Palliat Med 2012; 26: 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rothman DJ. Where we die. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2457–2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Robinson J, Gott M, Ingleton C. Patient and family experiences of palliative care in hospital: what do we know? An integrative review. Palliat Med 2014; 28: 18–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National Consensus Statement: essential elements for safe and high-quality end-of-life care in acute hospitals. Consultation draft, Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, Sydney, NSW, Australia, January 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hillman KM. End-of-life care in acute hospitals. Aust Health Rev 2011; 35: 176–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clark D, Armstrong M, Allan A, et al. Imminence of death among hospital inpatients: prevalent cohort study. Palliat Med 2014; 28: 474–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gott M, Ingleton C, Bennett MI, et al. Transitions to palliative care in acute hospitals in England: qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2011; 1: 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cohen J, Deliens L. (eds). A public health perspective on end of life care. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garner KK, Goodwin JA, McSweeney JC, et al. Nurse executives’ perceptions of end-of-life care provided in hospitals. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013; 45: 235–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Teno JM, Field MJ, Byock I. Preface: the road taken and to be traveled in improving end-of-life care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001; 22: 713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bretscher M. Caring for dying patients. What is right? J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kehl KA. Moving toward peace: an analysis of the concept of a good death. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2006; 23: 277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Preparing for the end of life: preferences of patients, families, physicians, and other care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001; 22: 727–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Steinhauser K, Christakis N, Clipp E, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 2000; 284: 2476–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S. The Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire: development and validation using data from in-patient surveys in five countries. Int J Qual Health Care 2002; 14: 353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stevenson A. Oxford dictionary of English. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Australian Government. Guidelines for a palliative approach in residential aged care. Canberra, ACT, Australia: Australian Government, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heyland D, Dodek P, Rocker G, et al. What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ 2006; 174: 627–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rocker GM, Dodek PM, Heyland DK. Toward optimal end-of-life care for patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights from a multicentre study. Can Respir J 2008; 15: 249–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). NHMRC additional levels of evidence and grades for recommendations for developers of guidelines. Canberra, ACT, Australia: NHMRC, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Osborn TR, Curtis JR, Nielsen EL, et al. Identifying elements of ICU care that families report as important but unsatisfactory: decision-making, control, and ICU atmosphere. Chest 2012; 1185–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gelfman LP, Meier DE, Morrison RS. Does palliative care improve quality? A survey of bereaved family members. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008; 36: 22–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moyano JR, Guerrero CE, Zambrano SC. Information on palliative care from the family’s perspective. Eur J Palliat Care 2007; 14: 117–119. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Heyland D, Groll D, Rocker G, et al. End-of-life care in acute care hospitals in Canada: a quality finish? J Palliat Care 2005; 21: 142–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baker R, Wu A, Teno J, et al. Family satisfaction with end-of-life care in seriously ill hospitalized adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48: S61–S69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kristjanson LJ. Quality of terminal care: salient indicators identified by families. J Palliat Care 1989; 5: 21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Young AJ, Rogers A, Dent L, et al. Experiences of hospital care reported by bereaved relatives of patients after a stroke: a retrospective survey using the VOICES questionnaire. J Adv Nurs 2009; 65: 2161–2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, et al. Defining priorities for improving end-of-life care in Canada. CMAJ 2010; 182: E747–E752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: A product from the ESRC Methods Programme, version 1, 2006. Lancaster: Institute of Health Research. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Palliative Care Australia. The hardest thing we have ever done. Canberra, ACT, Australia: Palliative Care Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Burge F, Lawson B, Johnston G, et al. Bereaved family member perceptions of patient-focused family-centred care during the last 30 days of life using a mortality follow-back survey: does location matter? BMC Palliat Care 2014; 13: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pruitt S, Epping-Jordan J. Innovative care for chronic conditions: building blocks for action: global report. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper: the basics of evidence-based medicine. 4th ed. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2010. [Google Scholar]