Abstract

The human propensity for high levels of serum uric acid (SUA) is a trait that has defied explanation. Is it beneficial? Is it pathogenic? Its role in the human diseases like gout and kidney stones was discovered over a century ago [Richette P, Bardin T. Lancet 375: 318–328, 2010; Rivard C, Thomas J, Lanaspa MA, Johnson RJ. Rheumatology (Oxford) 52: 421–426, 2013], but today emerging new genetic and epidemiological techniques have revived an age-old debate over whether high uric acid levels (hyperuricemia) independently increase risk for diseases like hypertension and chronic kidney disease [Feig DI. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 14: 346–352, 2012; Feig DI, Madero M, Jalal DI, Sanchez-Lozada LG, Johnson RJ. J Pediatr 162: 896–902, 2013; Feig DI, Soletsky B, Johnson RJ. JAMA 300: 924–932, 2008; Wang J, Qin T, Chen J, Li Y, Wang L, Huang H, Li J. PLoS One 9: e114259, 2014; Zhu P, Liu Y, Han L, Xu G, Ran JM. PLoS One 9: e100801, 2014]. Part of the mystery of the role uric acid plays in human health stems from our lack of understanding of how humans regulate uric acid homeostasis, an understanding that could shed light on the historic role of uric acid in human adaptation and its present role in human pathogenesis. This review will highlight the recent work to identify the first important human uric acid secretory transporter, ABCG2, and the identification of a common causal ABCG2 variant, Q141K, for hyperuricemia and gout.

Keywords: uric acid, kidney, ABCG2, Q141K, gout, hyperuricemia

uric acid is a terminal metabolite of the purine metabolic pathway in humans and is only weakly soluble in water or blood. In the mammalian lineage, there appears to be a concerted selection for decreasing the function of the enzyme that metabolizes uric acid, uricase, an adaptation culminating in the complete loss of uricase function in humans and other great apes (1). The selective advantage of uricase loss and higher serum uric acid (SUA) levels remains unknown, but the costs to humans are clear. The clinical disorder hyperuricemia, afflicting 43 million Americans, causes gout and urate kidney stones as a direct result of precipitation of urate in the form of monosodium urate crystals in either synovial fluid (gouty arthritis) or in the kidney tubule (uric acid kidney stones) (19). Gout is the best characterized result of hyperuricemia and afflicts 2–3% of Americans (13) [see Richette and Bardin (22) and Mount (19) for recent reviews on gout]. More recent work suggests hyperuricemia increases the risk for other human diseases as well. Feig et al. (7) recently argued that hyperuricemia has a causal role in hypertension in part based on a small-scale clinical trial of obese adolescents with prehypertension and hyperuricemia, who, when given urate-lowering therapy, demonstrated a significant reduction of blood pressure (27). On a larger scale, a recent meta-analysis of incident hypertension from 25 studies and 97,824 individuals found that overall SUA levels contributed a relative risk of 1.35, with an additional significant uric acid dose effect (29). Increased hypertension risk also translates to increased risk for other related disorders like stroke, metabolic disorders (22, 23), and chronic kidney disease (CKD), where SUA has been implicated as an increasing risk for incident CKD (relative risk of CKD was 1.22 per mg/dl of SUA) (34).

Hyperuricemia results primarily from underexcretion, which occurs via two primary pathways, the gut (30%) and the kidney (70%) (5, 22, 24). Work to describe the physiology of kidney excretion of uric acid was begun a half-century ago by the pioneering team of Gutman and Yu, when they proposed the three-component hypothesis of kidney uric acid filtration and excretion (5, 9, 10, 24): 1) uric acid is freely filtered at the glomerulus; 2) most uric acid is reabsorbed in the proximal tubule; and 3) some uric acid is actively secreted within the proximal tubule, distal to reabsorption. Subsequent decades only saw slight revisions of this theory, including a fourth postsecretory reabsorption component (24), but the central idea of a balance between reabsorption and secretion determining overall excretion remained. However, the advent of new molecular and genetic tools led to the molecular identification of most if not all of the key uric acid transporters in humans and allowed for the first time a high-resolution understanding of uric acid transport in the kidney [see Mandal and Mount for an excellent overview of the molecular players of uric acid homeostasis (13)]. Here, we focus exclusively on one gene and transporter gene product, ABCG2, its critical role in uric acid secretion, and a common ABCG2 causal variant for gout and hyperuricemia (28, 30–32).

The story of ABCG2 and uric acid began with an unbiased genetic screening tool, the genome-wide association study (GWAS). Dehghan et al. (3) conducted a GWAS on SUA and identified the first single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in a small region of chromosome 4 that associated with increased levels of SUA and gout (3). We showed that the gene ABCG2, located in the same region of chromosome 4, and which encodes an ABC (ATP-binding cassette) transporter (2), was a heretofore unknown urate efflux transporter (30). Using a Xenopus oocyte expression system, we demonstrated ABCG2 to be a high-capacity urate transporter with ABCG2-mediated c-14 uric acid efflux highly dependent on the intracellular concentration, and could be blocked by a specific ABCG2 inhibitor, FTC, or with a single amino acid substitution, S187A. Furthermore, endogenous ABCG2 in proximal tubule cells is localized to the apical brush border and critical for apical secretion of urate (30). Study of the most significant SNP that associated with SUA, rs2231142, revealed it codes for an amino acid Q-to-K substitution at position 141. We found the Q141K variant had similar total and surface expression levels in the Xenopus oocytes but showed a 54% reduction in urate transport, marking Q141K as a loss-of-function mutation (17, 18, 30). A population-based study of 14,783 individuals supported rs2231142 (Q141K) as a causal variant for gout and increased SUA levels, marking the rs2231142 as a rare example in support of the common disease-common variant hypothesis (30).

Subsequent, but independent work from Matsuo et al. (15) confirmed many of our findings. In a series of elegant papers, these same authors make a compelling argument for the critical importance of ABCG2 in gout and hyperuricemia risk. Matsuo et al. compared gouty and normal cohorts of Japanese males and found two ABCG2 mutations, Q141K (50% function) and Q126X (no function), and used these to correlate ABCG2 function with age of gout onset. They found that 76.2% of their gout cohort had some level of ABCG2 dysfunction and that severe ABCG2 dysfunction substantially increased the risk of early-onset gout (OR 22.2) (14). Nakayoma et al. (20) further calculated the population-attributable risk percentage (PAR%) for the major known hyperuricemia risk factors, including obesity, heavy drinking, age, and ABCG2 dysfunction. They calculated a PAR% for ABCG2 dysfunction at 29.2%, almost twice the next greatest contributor to risk, obesity (18.7%) (20). Taken with the high mutant allele frequency [the minor allele frequency of those of European decent is 0.11 (31), for Japanese is 0.31 (31), and for Han Chinese is 0.31 (33)]. ABCG2 dysfunction potentially puts hundreds of millions of individuals at increased risk for hyperuricemia and gout as well as hypertension, stroke, and metabolic diseases (7). Further large-scale genetic studies have also added significant support to the critical importance of ABCG2 in uric acid secretion. Kottgen et al. (12) used a GWAS to identify a total of 28 genome-wide significant loci that associated with SUA from a population of >140,000 individuals, predominantly of European origin (12). Of the 28 loci, the ABCG2 loci (rs2231142/Q141K mutation) resulted in the highest OR for gout risk (1.73) and contributed the largest increases in SUA (0.217 mg/dl) (12).

Recent work has focused on the molecular defect caused by the Q141K mutation of ABCG2 as both a potential therapeutic target and also as a model for understanding the basic structure/function biology of ABC transporters. The Q141K mutation occurs in a residue of the nucleotide-binding domain, a position believed critical for interactions with the intracellular loops of the transmembrane portion of the protein. Interestingly, the Q141 residue is adjacent to F142, a phenylalanine homologous to the F508 of CFTR, another human ABC transporter (ABCC7). This F508 is deleted in >90% of all cystic fibrosis patients, and considerable effort has been made to characterize its molecular defect (16, 21). A comparative analysis between the Q141K ABCG2 mutant and the ΔF508 CFTR mutant reveals striking similarities. Both mutants reduce innate function and result in significant reduction in total and surface expression (32). Both mutants can be corrected with low-temperature incubation techniques (4, 32), and both can be corrected with small molecules like 4-PBA (32). However, there are striking differences as well. The ΔF508 CFTR mutant is characterized by an unstable NBD domain and disruptions in interdomain interactions that lead to errors in protein folding (16, 21). The Q141K ABCG2 mutant appears to only cause instability in the NBD domain. We recently demonstrated that artificially stabilizing the NBD domain of the Q141K mutant corrects the molecular defect. Using either small molecules like the drug VRT-325 (11), or by using the suppressor mutation G188E to enhance NBD sandwich formation (25), we were able to rescue expression, trafficking, and function (32). Interestingly, we found that deleting the F142 residue in ABCG2 did phenocopy the more severe defect found in the homologous ΔF508 CFTR, including disrupted interdomain interactions with a dimerization defect. However, this conclusion remains controversial (32). Saranko et al. (26), in a follow-up study, found that the ΔF142 ABCG2 protein can dimerize when the mutant ABCG2 is expressed in the SF9 insect cell expression system grown at temperatures low enough to rescue misfolded mammalian proteins (4, 32). These conflicting findings need resolution as this may identify critical portions of the protein involved in protein folding and dimerization.

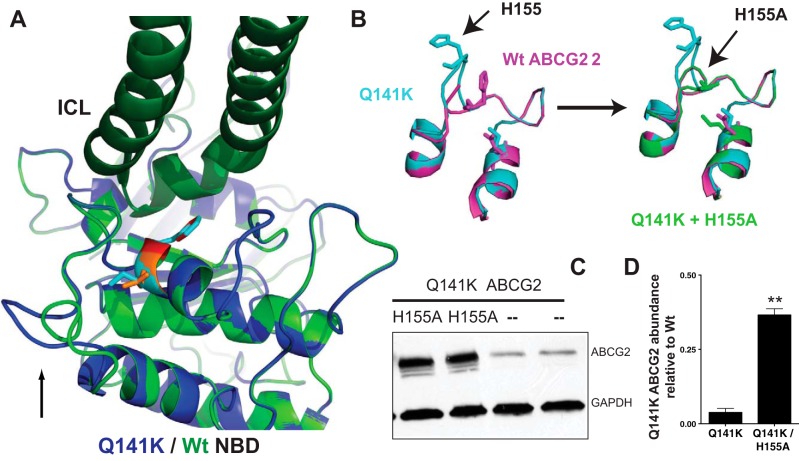

The specific source of the Q141K instability has remained unresolved. Recently, we have found that modeling the Q141K and Wt ABCG2 NBD domains (32) suggested a loop adjacent to the site of the Q141K substitution (see Fig. 1A) appears to be shifted outward, resulting from a clash between the mutant 141K residue and a histidine residue at the top of the loop. Replacing the histidine with an alanine appeared to resolve the shift and also significantly increased total Q141K (H155A) and mature, glycosylated protein abundance (Fig. 1, B–D) when expressed in HEK293 cells.

Fig. 1.

Q141K gout-causing mutation changes NBD structure in a model of ABCG2. A: model comparing Wt and Q141K NBDs as described in Woodward et al. (32) reveals a shift in an adjacent loop (black arrow, Q141K in blue, Wt in green). B: the H155 residue at the top of the loop clashes with the mutant 141K, causing a loop shift and is corrected in the model with a 155A substitution. C: biochemical confirmation of the model shows the Q141K mutant expression levels can be rescued with the secondary H155A substitution. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with ABCG2 constructs. Total protein was measured and normalized to GAPDH loading control and Wt ABCG2 expression from same Western blot. For details, see Ref. 32. D: summary data. Values are means ± SE, Student's t-test; n = 4. **P < 0.0001.

The study of uric acid in human health and physiology has entered a renaissance. Increased epidemiological data and small clinical trials have marked uric acid as a causal risk factor for hypertension and other important human diseases. These recent implications have been paralleled by the discovery of the molecular identities for many of transporters regulating the SUA levels, including the dominant secretory transporter ABCG2. Moving forward, learning more of how ABCG2 and the other urate transporters are physiologically regulated and the pathophysiology of their disease-causing variants will shed light on the long-disputed role of uric acid in human evolution and human health.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a number of grants including a Professional Development Award from the National Kidney Foundation of Maryland, Scientist Development Grant 14SDG18060004 from the American Heart Association, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases-sponsored Baltimore Polycystic Kidney Disease Research and Clinical Core Center, P30DK090868.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: O.M.W. provided conception and design of research; O.M.W. performed experiments; O.M.W. analyzed data; O.M.W. interpreted results of experiments; O.M.W. prepared figures; O.M.W. drafted manuscript; O.M.W. edited and revised manuscript; O.M.W. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chang BS. Ancient insights into uric acid metabolism in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 3657–3658, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dean M, Hamon Y, Chimini G. The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. J Lipid Res 42: 1007–1017, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dehghan A, Kottgen A, Yang Q, Hwang SJ, Kao WL, Rivadeneira F, Boerwinkle E, Levy D, Hofman A, Astor BC, Benjamin EJ, van Duijn CM, Witteman JC, Coresh J, Fox CS. Association of three genetic loci with uric acid concentration and risk of gout: a genome-wide association study. Lancet 372: 1953–1961, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drumm ML, Wilkinson DJ, Smit LS, Worrell RT, Strong TV, Frizzell RA, Dawson DC, Collins FS. Chloride conductance expressed by delta F508 and other mutant CFTRs in Xenopus oocytes. Science 254: 1797–1799, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esparza Martin N, Garcia Nieto V. Hypouricemia and tubular transport of uric acid. Nefrologia 31: 44–50, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feig DI. The role of uric acid in the pathogenesis of hypertension in the young. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 14: 346–352, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feig DI, Madero M, Jalal DI, Sanchez-Lozada LG, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and the origins of hypertension. J Pediatr 162: 896–902, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feig DI, Soletsky B, Johnson RJ. Effect of allopurinol on blood pressure of adolescents with newly diagnosed essential hypertension: a randomized trial. JAMA 300: 924–932, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gutman AB, Yu TF. Renal regulation of uric acid excretion in normal and gouty man; modification by uricosuric agents. Bull NY Acad Med 34: 287–296, 1958. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutman AB, Yu TF. A three-component system for regulation of renal excretion of uric acid in man. Trans Assoc Am Physicians 74: 353–365, 1961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim Chiaw P, Wellhauser L, Huan LJ, Ramjeesingh M, Bear CE. A chemical corrector modifies the channel function of F508del-CFTR. Mol Pharmacol 78: 411–418, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kottgen A, Albrecht E, Teumer A, Vitart V, Krumsiek J, Hundertmark C, Pistis G, Ruggiero D, O'Seaghdha CM, Haller T, Yang Q, Tanaka T, Johnson AD, Kutalik Z, Smith AV, Shi J, Struchalin M, Middelberg RP, Brown MJ, Gaffo AL, Pirastu N, Li G, Hayward C, Zemunik T, Huffman J, Yengo L, Zhao JH, Demirkan A, Feitosa MF, Liu X, Malerba G, Lopez LM, van der Harst P, Li X, Kleber ME, Hicks AA, Nolte IM, Johansson A, Murgia F, Wild SH, Bakker SJ, Peden JF, Dehghan A, Steri M, Tenesa A, Lagou V, Salo P, Mangino M, Rose LM, Lehtimaki T, Woodward OM, Okada Y, Tin A, Muller C, Oldmeadow C, Putku M, Czamara D, Kraft P, Frogheri L, Thun GA, Grotevendt A, Gislason GK, Harris TB, Launer LJ, McArdle P, Shuldiner AR, Boerwinkle E, Coresh J, Schmidt H, Schallert M, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, Kubo M, Nakamura Y, Tanaka T, Munroe PB, Samani NJ, Jacobs DR Jr, Liu K, D'Adamo P, Ulivi S, Rotter JI, Psaty BM, Vollenweider P, Waeber G, Campbell S, Devuyst O, Navarro P, Kolcic I, Hastie N, Balkau B, Froguel P, Esko T, Salumets A, Khaw KT, Langenberg C, Wareham NJ, Isaacs A, Kraja A, Zhang Q, Wild PS, Scott RJ, Holliday EG, Org E, Viigimaa M, Bandinelli S, Metter JE, Lupo A, Trabetti E, Sorice R, Doring A, Lattka E, Strauch K, Theis F, Waldenberger M, Wichmann HE, Davies G, Gow AJ, Bruinenberg M, LifeLines Cohort Study , Stolk RP, Kooner JS, Zhang W, Winkelmann BR, Boehm BO, Lucae S, Penninx BW, Smit JH, Curhan G, Mudgal P, Plenge RM, Portas L, Persico I, Kirin M, Wilson JF, Mateo Leach I, van Gilst WH, Goel A, Ongen H, Hofman A, Rivadeneira F, Uitterlinden AG, Imboden M, von Eckardstein A, Cucca F, Nagaraja R, Piras MG, Nauck M, Schurmann C, Budde K, Ernst F, Farrington SM, Theodoratou E, Prokopenko I, Stumvoll M, Jula A, Perola M, Salomaa V, Shin SY, Spector TD, Sala C, Ridker PM, Kahonen M, Viikari J, Hengstenberg C, Nelson CP, Consortium CA, Consortium D, Consortium I, Consortium M, Meschia JF, Nalls MA, Sharma P, Singleton AB, Kamatani N, Zeller T, Burnier M, Attia J, Laan M, Klopp N, Hillege HL, Kloiber S, Choi H, Pirastu M, Tore S, Probst-Hensch NM, Volzke H, Gudnason V, Parsa A, Schmidt R, Whitfield JB, Fornage M, Gasparini P, Siscovick DS, Polasek O, Campbell H, Rudan I, Bouatia-Naji N, Metspalu A, Loos RJ, van Duijn CM, Borecki IB, Ferrucci L, Gambaro G, Deary IJ, Wolffenbuttel BH, Chambers JC, Marz W, Pramstaller PP, Snieder H, Gyllensten U, Wright AF, Navis G, Watkins H, Witteman JC, Sanna S, Schipf S, Dunlop MG, Tonjes A, Ripatti S, Soranzo N, Toniolo D, Chasman DI, Raitakari O, Kao WH, Ciullo M, Fox CS, Caulfield M, Bochud M, Gieger C. Genome-wide association analyses identify 18 new loci associated with serum urate concentrations. Nat Genet 45: 145–154, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandal AK, Mount DB. The molecular physiology of uric acid homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol 77: 323–345, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuo H, Ichida K, Takada T, Nakayama A, Nakashima H, Nakamura T, Kawamura Y, Takada Y, Yamamoto K, Inoue H, Oikawa Y, Naito M, Hishida A, Wakai K, Okada C, Shimizu S, Sakiyama M, Chiba T, Ogata H, Niwa K, Hosoyamada M, Mori A, Hamajima N, Suzuki H, Kanai Y, Sakurai Y, Hosoya T, Shimizu T, Shinomiya N. Common dysfunctional variants in ABCG2 are a major cause of early-onset gout. Sci Rep 3: 2014, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuo H, Takada T, Ichida K, Nakamura T, Nakayama A, Ikebuchi Y, Ito K, Kusanagi Y, Chiba T, Tadokoro S, Takada Y, Oikawa Y, Inoue H, Suzuki K, Okada R, Nishiyama J, Domoto H, Watanabe S, Fujita M, Morimoto Y, Naito M, Nishio K, Hishida A, Wakai K, Asai Y, Niwa K, Kamakura K, Nonoyama S, Sakurai Y, Hosoya T, Kanai Y, Suzuki H, Hamajima N, Shinomiya N. Common defects of ABCG2, a high-capacity urate exporter, cause gout: a function-based genetic analysis in a Japanese population. Sci Transl Med 1: 5ra11, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendoza JL, Schmidt A, Li Q, Nuvaga E, Barrett T, Bridges RJ, Feranchak AP, Brautigam CA, Thomas PJ. Requirements for efficient correction of DeltaF508 CFTR revealed by analyses of evolved sequences. Cell 148: 164–174, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mizuarai S, Aozasa N, Kotani H. Single nucleotide polymorphisms result in impaired membrane localization and reduced ATPase activity in multidrug transporter ABCG2. Int J Cancer 109: 238–246, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morisaki K, Robey RW, Ozvegy-Laczka C, Honjo Y, Polgar O, Steadman K, Sarkadi B, Bates SE. Single nucleotide polymorphisms modify the transporter activity of ABCG2. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 56: 161–172, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mount DB. The kidney in hyperuricemia and gout. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 22: 216–223, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakayama A, Matsuo H, Nakaoka H, Nakamura T, Nakashima H, Takada Y, Oikawa Y, Takada T, Sakiyama M, Shimizu S, Kawamura Y, Chiba T, Abe J, Wakai K, Kawai S, Okada R, Tamura T, Shichijo Y, Akashi A, Suzuki H, Hosoya T, Sakurai Y, Ichida K, Shinomiya N. Common dysfunctional variants of ABCG2 have stronger impact on hyperuricemia progression than typical environmental risk factors. Sci Rep 4: 5227, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabeh WM, Bossard F, Xu H, Okiyoneda T, Bagdany M, Mulvihill CM, Du K, di Bernardo S, Liu Y, Konermann L, Roldan A, Lukacs GL. Correction of both NBD1 energetics and domain interface is required to restore DeltaF508 CFTR folding and function. Cell 148: 150–163, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richette P, Bardin T. Gout. Lancet 375: 318–328, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rivard C, Thomas J, Lanaspa MA, Johnson RJ. Sack and sugar, and the aetiology of gout in England between 1650 and 1900. Rheumatology (Oxford) 52: 421–426, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roch-Ramel F, Werner D, Guisan B. Urate transport in brush-border membrane of human kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 266: F797–F805, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roxo-Rosa M, Xu Z, Schmidt A, Neto M, Cai Z, Soares CM, Sheppard DN, Amaral MD. Revertant mutants G550E and 4RK rescue cystic fibrosis mutants in the first nucleotide-binding domain of CFTR by different mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 17891–17896, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saranko H, Tordai H, Telbisz A, Ozvegy-Laczka C, Erdos G, Sarkadi B, Hegedus T. Effects of the gout-causing Q141K polymorphism and a CFTR DeltaF508 mimicking mutation on the processing and stability of the ABCG2 protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 437: 140–145, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soletsky B, Feig DI. Uric acid reduction rectifies prehypertension in obese adolescents. Hypertension 60: 1148–1156, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tin A, Woodward OM, Kao WH, Liu CT, Lu X, Nalls MA, Shriner D, Semmo M, Akylbekova EL, Wyatt SB, Hwang SJ, Yang Q, Zonderman AB, Adeyemo AA, Palmer C, Meng Y, Reilly M, Shlipak MG, Siscovick D, Evans MK, Rotimi CN, Flessner MF, Kottgen M, Cupples LA, Fox CS, Kottgen A, Care Consortia C. Genome-wide association study for serum urate concentrations and gout among African Americans identifies genomic risk loci and a novel URAT1 loss-of-function allele. Hum Mol Genet 20: 4056–4068, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Qin T, Chen J, Li Y, Wang L, Huang H, Li J. Hyperuricemia and risk of incident hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS One 9: e114259, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woodward OM, Kottgen A, Coresh J, Boerwinkle E, Guggino WB, Kottgen M. Identification of a urate transporter, ABCG2, with a common functional polymorphism causing gout. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 10338–10342, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woodward OM, Kottgen A, Kottgen M. ABCG transporters and disease. FEBS J 278: 3215–3225, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woodward OM, Tukaye DN, Cui J, Greenwell P, Constantoulakis LM, Parker BS, Rao A, Kottgen M, Maloney PC, Guggino WB. Gout-causing Q141K mutation in ABCG2 leads to instability of the nucleotide-binding domain and can be corrected with small molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 5223–5228, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou D, Liu Y, Zhang X, Gu X, Wang H, Luo X, Zhang J, Zou H, Guan M. Functional polymorphisms of the ABCG2 gene are associated with gout disease in the Chinese Han male population. Int J Mol Sci 15: 9149–9159, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu P, Liu Y, Han L, Xu G, Ran JM. Serum uric acid is associated with incident chronic kidney disease in middle-aged populations: a meta-analysis of 15 cohort studies. PLoS One 9: e100801, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]