Abstract

Exposure to moderate hyperoxia in prematurity contributes to subsequent airway dysfunction and increases the risk of developing recurrent wheeze and asthma. The nitric oxide (NO)-soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC)-cyclic GMP (cGMP) axis modulates airway tone by regulating airway smooth muscle (ASM) intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) and contractility. However, the effects of hyperoxia on this axis in the context of Ca2+/contractility are not known. In developing human ASM, we explored the effects of novel drugs that activate sGC independent of NO on alleviating hyperoxia (50% oxygen)-induced enhancement of Ca2+ responses to bronchoconstrictor agonists. Treatment with BAY 41–2272 (sGC stimulator) and BAY 60-2770 (sGC activator) increased cGMP levels during exposure to 50% O2. Although 50% O2 did not alter sGCα1 or sGCβ1 expression, BAY 60-2770 did increase sGCβ1 expression. BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770 blunted Ca2+ responses to histamine in cells exposed to 50% O2. The effects of BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770 were reversed by protein kinase G inhibition. These novel data demonstrate that BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770 stimulate production of cGMP and blunt hyperoxia-induced increases in Ca2+ responses in developing ASM. Accordingly, sGC stimulators/activators may be a useful therapeutic strategy in improving bronchodilation in preterm infants.

Keywords: lung, prematurity, calcium, cGMP, pediatric asthma

supplemental oxygen remains a necessary therapy for preterm infants, but unfortunately, it contributes to development of long-term recurrent wheeze and asthma (6, 27). In neonatal intensive care, supplemental oxygen is limited to moderate levels (40–50%) (1, 23), but survivors of this critical period continue to suffer from chronic airway disease (21, 25) and are at high risk for airway hyperreactivity (17).

Although the mechanisms underlying airway dysfunction are still under investigation, given that airway smooth muscle (ASM) is key to the regulation of airway tone (30), it is important to understand factors that regulate ASM function or its modulation in prematurity. Airway epithelium can release nitric oxide (NO) that stimulates ASM soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) to produce cGMP, which can then induce bronchodilation (18). Thus enhancement of the NO-sGC-cGMP axis could help induce bronchodilation and improve airway function in at-risk preterm infants. However, the interaction between hyperoxia and this axis in developing ASM is unknown.

The β-subunit of sGC avidly binds heme and is the target of NO in stimulating cGMP production (14). In a prooxidant environment (e.g., low or high oxygen), heme-containing sGCβ is vulnerable to oxidation, leading to inactivation and degradation, and could thus make NO ineffective in activating sGC (14). In developing lung, sGC and cGMP are important for growth and function (3). Hyperoxia diminishes sGC activity in the newborn lung, resulting in impaired alveolar maturation and airway relaxation (2, 4). Newborn sGCα1−/− pups show reduced lung sGC activity and exhibit worsened alveolar development following 70% O2 exposure (3). In fetal lambs, hypoxia reduces sGC expression in pulmonary artery smooth muscle (7). These data highlight the importance of sGC and its dysfunction in developing lung in the context of oxygen exposure, but interactions between hyperoxia and sGC in conducting airways in early postnatal development are not known.

Recently, novel compounds have been developed to directly stimulate sGC activity in the absence of NO (33). sGC stimulators (e.g., BAY 41-2272) induce cGMP production independent of NO, but only when sGCβ is bound to reduced heme (33). Complementarily, sGC activators (e.g., BAY 60-2770) stimulate cGMP production, when sGCβ heme is oxidized. The advantage of sGC activators is that they can maintain cGMP production in prooxidative environments (33). In a recent study, BAY 41-2272 was found to relax rat ASM tracheal rings stimulated with carbachol (36), whereas another sGC activator, BAY 58-2667, was found to reduce mouse airway resistance during cigarette smoke exposure (16). BAY 41-2272 was recently shown to enhance vasodilation in the newborn lung (11); however, the effects of sGC stimulators/activators on the developing airway per se have yet to be explored. Given the potential for sGC stimulators/activators in improving airway function, we used human fetal ASM cells (8, 19) as an in vitro model of the developing airway to evaluate the effect of sGC stimulation (BAY 41-2272) and activation (BAY 60-2770) on Ca2+ responses following exposure to moderate hyperoxia (50% O2).

METHODS

Isolation of human fetal ASM cells.

As described previously (8, 19), cells were obtained in collaboration with Dr. Hitesh Pandya (University of Leicester, Leicester, UK) or from Novogenix (Los Angeles, CA). Cells were isolated from deidentified tracheobronchial tissue following fetal demise (18–22 wk gestation; approved and considered exempt by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and UK Ethics Committees). We have demonstrated previously that these ASM cells consistently express smooth muscle markers and Ca2+ regulatory proteins as well as display robust intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) responses to bronchoconstrictor agonists (8, 19).

Treatments.

Fetal ASM cells were grown as described previously (8, 19). Cells were serum starved in 0.5% fetal bovine serium for 24 h prior to experimentation. Cells were then treated with vehicle (DMSO), 10 μM BAY 41-2272, 10 μM BAY 60-2770, 500 nM KT-5823 [protein kinase G (PKG) inhibitor] or 10 μM 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ; a sGC inhibitor) for 30 min and then exposed to 21 or 50% O2 for 24 or 48 h in the continued presence of any of these compounds. Drug concentrations were based on recent studies in related models (9). The use of 50% O2 was based on the increasing clinical adoption of moderate hyperoxia as well as recent studies (19, 35) showing increased [Ca2+]i and proliferation at 40–50% oxygen.

cGMP measurements.

In the above groups, culture medium was supplemented with 10 μM IBMX [phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitor] prior to compound or oxygen exposure. After 48 h, cells were harvested, and 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added for protein precipitation. To remove TCA, a 5× volume of saturated ether was added. Samples were vortexed, layers were allowed to separate, and the top layer (ether) was extracted three times. cGMP levels in media were measured by ELISA (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA), following the manufacturer's protocol. Absorbance was measured using a Flexstation 3 plate reader (Molecular Devices) at 410 nM, and a standard curve was used to determine cGMP concentration.

PDE activity.

A cyclic nucleotide PDE activity kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY) was used to measure PDE5 activity in cell lysates. Briefly, fetal ASM cells were harvested using a PDE assay buffer containing 10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4. Extracts containing 2.5 μg of protein were then incubated with 3′,5′-cAMP and 5′-nucleotidase (final concentrations of 200 μM and 50 kU, respectively) in the presence or absence of a PDE5 inhibitior (10 μM sildenafil; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) for 60 min at 30°C. The reaction was terminated using Biomol Green reagent, and after 30 min for color development, optical density was determined at 620 nm. PDE5 activity was calculated by comparing the amount of phosphate released from samples incubated with vs. without sildenafil and normalized to the amount of protein in cell lysate.

Western blot analysis.

Cells were harvested in lysis buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor tablet (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Standard SDS-PAGE with nitrocellulose membrane transfer techniques were used. Primary antibodies were sGCα1 and sGCβ1 (Cayman Chemical) and GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Following far red secondary antibody incubation, membranes were imaged on a Li-Cor OdysseyXL system, and quantitative densitometry was performed. Protein blots were normalized to β-actin.

Ca2+ responses.

Techniques for [Ca2+]i measurements in fetal ASM cells have been described previously (35). Briefly, cells were loaded with 5 μM Fluo-4/AM (Ca2+ indicator) and imaged (∼20 cells/field) in real time using a Nikon microscope-based fluorescence imaging system (×200 magnification, 1 Hz sampling). Histamine (10 μM) was used as an agonist. Responses are calculated by comparing the ratio of peak fluorescence with the average baseline fluorescence.

Statistics.

ASM cells from three to four fetuses were used. Each experiment utilized multiple repetitions per sample. Data are presented as means ± SE and were analyzed by unpaired t-tests. Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

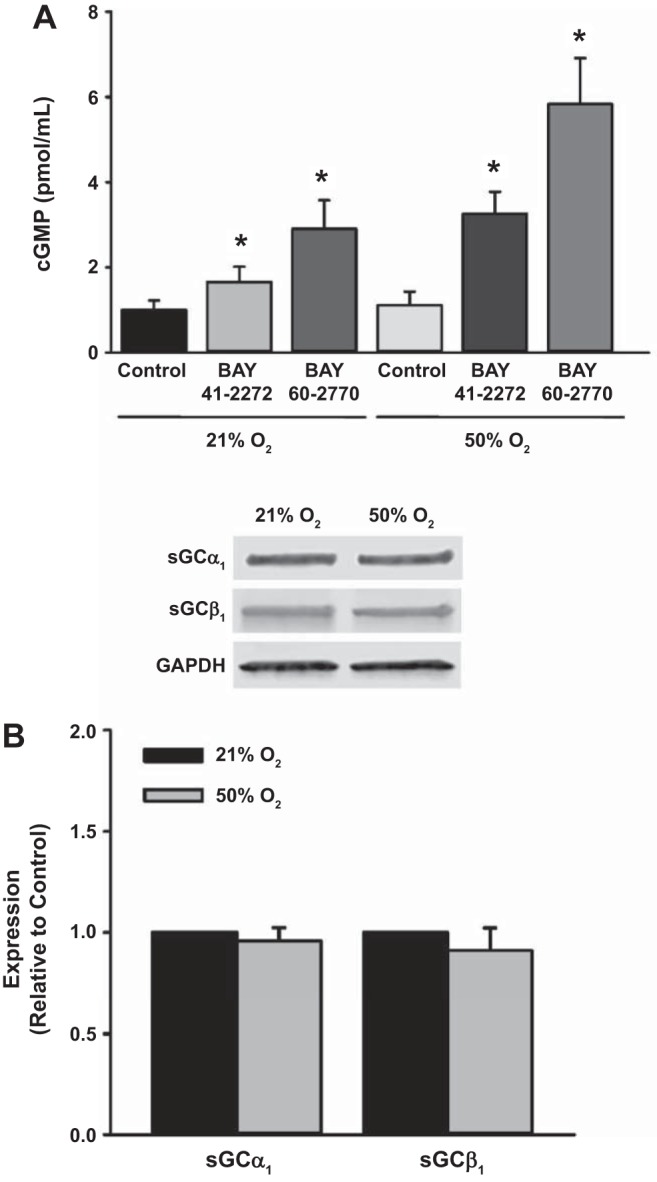

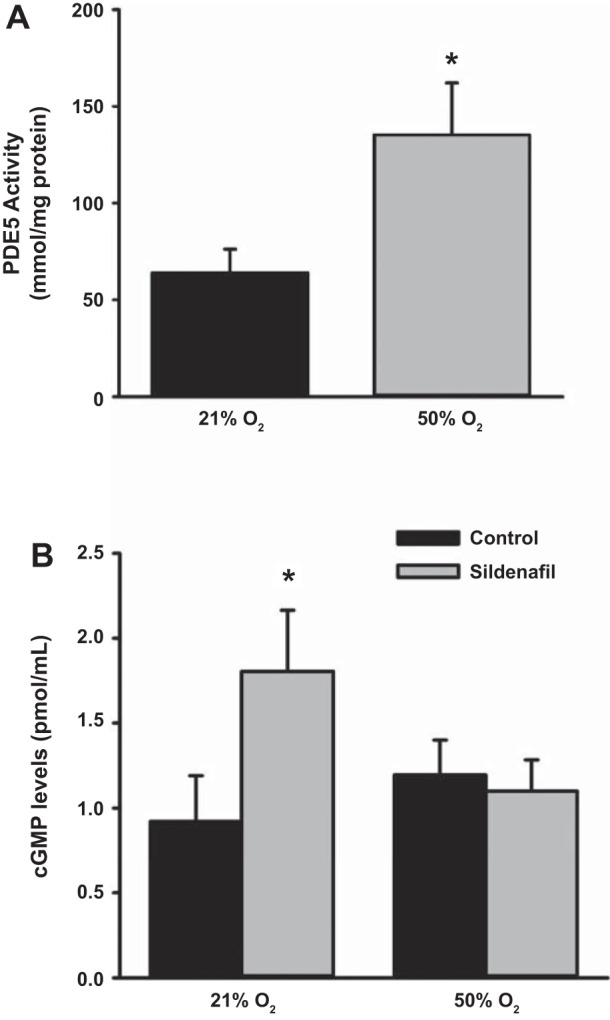

BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770 stimulate cGMP production.

Fetal ASM cells were treated with vehicle, BAY 41-2272 (sGC stimulator), or BAY 60-2770 (sGC activator) and then exposed to 21 or 50% O2 for 48 h. Treatment with BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770 during exposure to 21% O2 as well as 50% O2 significantly increased cGMP levels, with a greater effect for BAY 60-2770 (Fig. 1A). Exposure to 50% O2 did not alter cGMP levels or expression of sGCα1 and sGCβ1 (Fig. 1B). Cells exposed to 50% O2 showed greater PDE5 activity compared with 21% O2-exposed cells (Fig. 2A), and although treatment with sildenafil, a PDE5 inhibitor, increased cGMP levels in 21% O2-exposed cells (Fig. 2B), cGMP levels were not altered by exposure to 50% O2.

Fig. 1.

Effect of BAY 41-2272 [soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulator] and BAY 60-2770 (sGC activator) on cGMP levels during exposure to 50% O2 in human fetal airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells. A: BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770 each increased cGMP during 50% O2 exposure. B: expression of sGCα1 and sGCβ1 was not altered by 50% O2. Data represent means ± SE; n = 4 samples, P < 0.05. *Significant effects of BAY 41-2272 or BAY 60-2770.

Fig. 2.

Effect of hyperoxia on phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) activity in human fetal ASM cells. A: compared with control, 50% O2 for 48 h increased PDE5 activity. B: treatment with the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil increased cGMP in 21% O2 but not 50% O2. Data represent means ± SE; n = 3 samples, P < 0.05. *Significant difference from 21% O2.

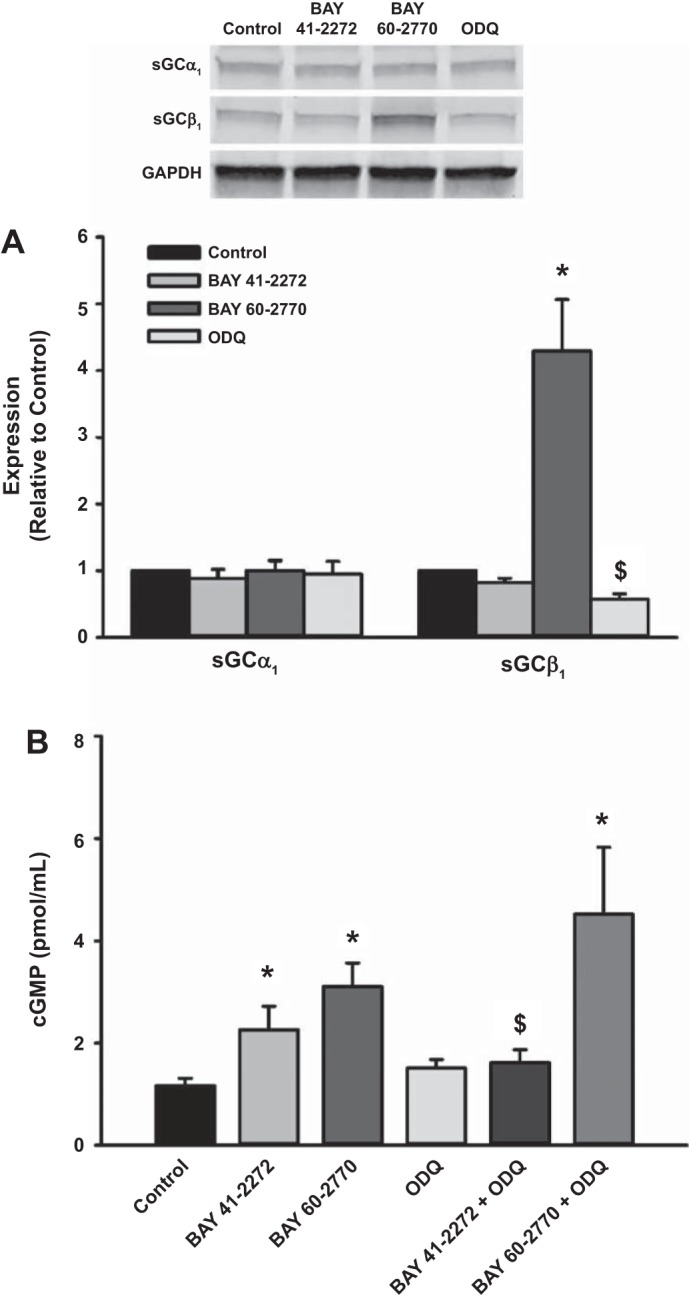

Differences between BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770.

Previous studies have demonstrated that, in contrast to sGC stimulators such as BAY 41-2272, sGC activators (e.g., BAY 60-2770) stimulate cGMP production when sGCβ is oxidized (33). Fetal ASM cells were treated with vehicle or ODQ for 30 min and then treated with vehicle, BAY 41-2272, or BAY 60-2770 for 24 h. BAY 60-2770, but not BAY 41-2272, increased sGCβ1 expression, whereas treatment with ODQ (a sGCβ oxidizer and inhibitor) reduced sGCβ1 protein levels (Fig. 3A). Expression of sGCα1 was not altered by BAY 41-2272, BAY 60-2770, or ODQ (Fig. 3A). Both BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770 increased cGMP levels; however, in the presence of ODQ, BAY 41-2272 was not able to enhance cGMP levels (Fig. 3B). In contrast, BAY 60-2770's effects on cGMP levels were unaffected in the presence of ODQ (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Differences between BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770. A: sGCβ1 expression was decreased by the sGC inhibitor 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ), whereas BAY 60-2770 increased its expression. Expression of sGCα1 remained unaltered. B: ODQ prevented BAY 41-2272 from increasing cGMP, whereas BAY 60-2770 retained its ability to increase cGMP. Data represent means ± SE; n = 4 samples, P < 0.05. *Significant effect of BAY 60-2770; $significant effect of ODQ.

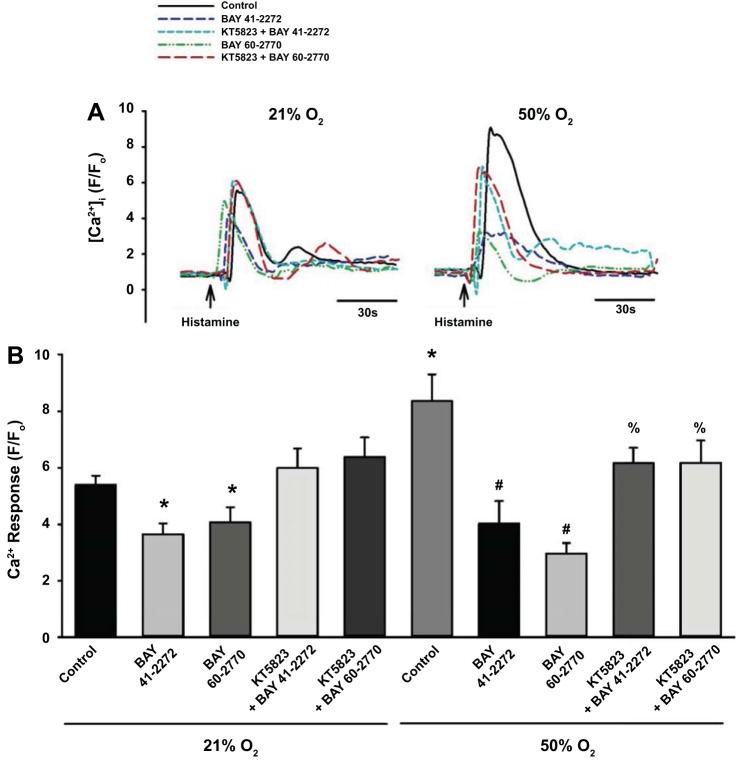

Effect of BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770 on [Ca2+]i responses.

Exposure to hyperoxia stimulates mechanisms that contribute to hypercontractility in developing ASM cells (35). Treatment with BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770 blunted the enhancing effects of 50% O2 on [Ca2+]i responses to histamine (Fig. 4). PKG is activated by cGMP and negatively regulates multiple Ca2+ influx mechanisms (13). In the presence of the PKG inhibitor KT-5823, the effects of BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770 were significantly inhibited during exposure to 50% O2 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect of BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770 on Ca2+ response during hyperoxia exposure. A: both BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770 blunted hyperoxia-induced enhancement of Ca2+ responses to histamine. Effects of the BAY compounds were inhibited by KT-5823 (PKG inhibitor). Tracings are representative of 3 independent experiments. B: data represent means ± SE; n = 3 samples, P < 0.05. *Significant difference from 21% O2; #significant difference, effects of BAY 41-2272 or BAY 60-2770; %significant difference, effect of KT-5823.

DISCUSSION

Hyperoxia exposure in prematurity is a significant risk factor for subsequent airway disease in children (17, 27). Previous studies in newborn rodents demonstrate that hyperoxia enhances airway contractility and impairs relaxation (32, 37), and we showed previously that hyperoxia enhances [Ca2+]i responses of developing human ASM cells (35) from a gestational age when rapid airway growth occurs and is not too distant from the age of at-risk premature infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. A number of mechanisms contribute to hyperoxia's effects on airway contractility and relaxation, including increasing IP3 receptor activity via oxidation (26), autocrine effects of procontractile factors that enhance ASM Ca2+ influx (35), and disruption of the NO-sGC-cGMP axis (22, 32). The NO-sGC-cGMP axis may be particularly important in neonatal lung since cGMP modulates Ca2+ channels and other signaling proteins relevant to ASM contractility and relaxation (18, 24). Furthermore, PKG has a number of downstream targets that are important to airway and lung growth. Our novel findings show that sGC activation can increase cGMP production in developing ASM and blunt enhancing effects of hyperoxia on agonist-induced Ca2+ responses. Such effects on cGMP as well as Ca2+ could potentially influence airway structure and function in the short-term via contractility and in the long term via genomic effects. Accordingly, this initial study is significant given the need to identify therapies to alleviate the detrimental effects of hyperoxia on the developing airway.

Hyperoxia increases Ca2+ response of fetal ASM cells to agonist (35). Our data now show that such hyperoxia effects are blunted by BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770. Here, PKG appears to be an important intermediary. There are multiple mechanisms by which PKG can modulate Ca2+ responses, including inhibition of Ca2+ influx channels, Rho kinase, and activation of myosin light chain phosphatase (13). The role of PKG in the developing lung remains undefined. However, in human ASM, cGMP modulates multiple mechanisms, including sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ loading (5), Ca2+ oscillations (29), and relaxation mechanisms (15). Some of these mechanisms are known to be dysfunctional in hyperoxia-exposed fetal ASM, as reported previously (19). Accordingly, sGC activators and stimulators may be beneficial in reversing dysfunctional Ca2+ regulation in the developing airway.

Surprisingly, we found that hyperoxia did not alter expression of sGCα1 and sGCβ1 or cGMP levels. This is in contrast to recent studies in mice reporting that prooxidant insults such as cigarette smoke and allergens reduce sGCα1 and sGCβ1 expression (28, 38). We also found that hyperoxia did not alter cGMP levels, although PDE5 activity was increased. Previous studies show that oxidative stress increases PDE5 activity in adult pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and contributes to vascular dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension (12). The role of PDE5 in the regulation of airway tone in the developing human airway, especially in the context of hyperoxia, is less understood. Our studies suggest that PDE5 may not have a prominent role in regulating cGMP levels during exposure to moderate hyperoxia. Indeed, there are additional factors, including particulate sGCs and other PDE isoforms, that also regulate cGMP levels. Previous studies have identified PDE1, -2, -3, -4, and -5 in ASM (31), and all except PDE4 can target cGMP for degradation (39). Although inhibition of PDE5 is a potent pulmonary vasodilator (12, 20), the role of PDE5 and other isoforms in dilation of the developing airway is less clear. Accordingly, it is possible that hyperoxia modulates other PDE isoforms or factors with downstream effects on cGMP.

We compared the effects of sGC stimulation (BAY 41-2272) vs. activation (BAY 60-2770) on cGMP levels and Ca2+ responses. Although both approaches increased cGMP levels during exposure to hyperoxia, we also demonstrated differences between the two compounds. Oxidation of the sGCβ heme results in proteasomal degradation and reduces sGC activity (20). sGC activators such as BAY 60-2770 stabilize oxidized sGCβ and enhance its ability to produce cGMP. In contrast, BAY 41-2272 requires sGCβ to be bound to reduced heme (33). Unlike BAY 41-2272, BAY 60-2770 was able to increase cGMP levels in the presence of ODQ and increase sGCβ1 expression in fetal ASM. In fetal pulmonary artery smooth muscle, another sGC activator, BAY 58-2667, enhances cGMP levels during oxidative stress induced by hyperoxia or H2O2 (9) and enhances vasodilation during vascular injury (34). In the context of hyperoxia and preterm infants, the functional differences between sGC stimulators and activators are important. Although our studies demonstrate that BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770 were both able to increase cGMP during hyperoxia, the preterm infant lung is likely to be a more prooxidant environment. Thus sGC activators that modulate oxidized sGC may be more helpful for infants on respiratory support.

Targeting and activating sGC, particularly in the context of oxidized sGC, has been shown to alleviate pulmonary hypertension and enhance sGC activation in cardiovascular disease (33). Modulation of sGC is being explored for targeting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (10). Maintaining homeostatic airway function is critical for newborn infants, particularly given an already compliant lung and chest wall, and in the longer term increases the risk of recurrent wheeze or asthma. Our data show that sGC stimulators and activators increase cGMP levels and blunt enhanced Ca2+ responses that occur with hyperoxia. In future studies, it will be important to investigate how sGC modulators affect additional factors related to ASM contractility, such as cell shape, cytoskeleton remodeling, and extracellular matrix interactions. Since preterm infants are exposed to supraphysiological oxygen levels while in intensive care, the use of sGC stimulators/activators may be an advantageous therapy for neonates at risk of developing airway disease.

GRANTS

These studies were supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants F32-HL-123075 (R. D. Britt, Jr.), R01-HL-056470 (Y. S. Prakash and R. J. Martin), R01-HL-088029 (Y. S. Prakash), and T32-HL-105355 (R. D. Britt, Jr., and E. R. Vogel).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.D.B.J., M.A.T., R.J.M., C.M.P., and Y.S.P. conception and design of research; R.D.B.J., M.A.T., I.K., A.S., E.R.V., and J.T. performed experiments; R.D.B.J., M.A.T., I.K., A.S., E.R.V., and J.T. analyzed data; R.D.B.J., M.A.T., I.K., A.S., E.R.V., R.J.M., C.M.P., and Y.S.P. interpreted results of experiments; R.D.B.J. and M.A.T. prepared figures; R.D.B.J. and M.A.T. drafted manuscript; R.D.B.J., M.A.T., I.K., R.J.M., C.M.P., and Y.S.P. edited and revised manuscript; R.D.B.J., M.A.T., I.K., A.S., E.R.V., J.T., R.J.M., C.M.P., and Y.S.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Johannes-Peter Stasch (Bayer Healthcare) for providing us with BAY 41-2272 and BAY 60-2770.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abman SH. The dysmorphic pulmonary circulation in bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a growing story. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 178: 114–115, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali NK, Jafri A, Sopi RB, Prakash YS, Martin RJ, Zaidi SI. Role of arginase in impairing relaxation of lung parenchyma of hyperoxia-exposed neonatal rats. Neonatology 101: 106–115, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachiller PR, Cornog KH, Kato R, Buys ES, Roberts JD Jr. Soluble guanylate cyclase modulates alveolarization in the newborn lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 305: L569–L581, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachiller PR, Nakanishi H, Roberts JD Jr. Transforming growth factor-β modulates the expression of nitric oxide signaling enzymes in the injured developing lung and in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 298: L324–L334, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bazan-Perkins B. cGMP reduces the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ loading in airway smooth muscle cells: a putative mechanism in the regulation of Ca2+ by cGMP. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 32: 375–382, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Been JV, Lugtenberg MJ, Smets E, van Schayck CP, Kramer BW, Mommers M, Sheikh A. Preterm birth and childhood wheezing disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 11: e1001596, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bland RD, Ling CY, Albertine KH, Carlton DP, MacRitchie AJ, Day RW, Dahl MJ. Pulmonary vascular dysfunction in preterm lambs with chronic lung disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 285: L76–L85, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Britt RD Jr, Faksh A, Vogel ER, Thompson MA, Chu V, Pandya HC, Amrani Y, Martin RJ, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS. Vitamin D attenuates cytokine-induced remodeling in human fetal airway smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol 230: 1189–1198, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chester M, Seedorf G, Tourneux P, Gien J, Tseng N, Grover T, Wright J, Stasch JP, Abman SH. Cinaciguat, a soluble guanylate cyclase activator, augments cGMP after oxidative stress and causes pulmonary vasodilation in neonatal pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 301: L755–L764, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dupont LL, Glynos C, Bracke KR, Brouckaert P, Brusselle GG. Role of the nitric oxide-soluble guanylyl cyclase pathway in obstructive airway diseases. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 29: 1–6, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enomoto M, Jain A, Pan J, Shifrin Y, Van Vliet T, McNamara PJ, Jankov RP, Belik J. Newborn rat response to single vs. combined cGMP-dependent pulmonary vasodilators. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 306: L207–L215, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrow KN, Groh BS, Schumacker PT, Lakshminrusimha S, Czech L, Gugino SF, Russell JA, Steinhorn RH. Hyperoxia increases phosphodiesterase 5 expression and activity in ovine fetal pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 102: 226–233, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Francis SH, Busch JL, Corbin JD, Sibley D. cGMP-dependent protein kinases and cGMP phosphodiesterases in nitric oxide and cGMP action. Pharmacol Rev 62: 525–563, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friebe A, Koesling D. Regulation of nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase. Circ Res 93: 96–105, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaston B, Drazen JM, Jansen A, Sugarbaker DA, Loscalzo J, Richards W, Stamler JS. Relaxation of human bronchial smooth muscle by S-nitrosothiols in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 268: 978–984, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glynos C, Dupont LL, Vassilakopoulos T, Papapetropoulos A, Brouckaert P, Giannis A, Joos GF, Bracke KR, Brusselle GG. The role of soluble guanylyl cyclase in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188: 789–799, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halvorsen T, Skadberg BT, Eide GE, Roksund O, Aksnes L, Oymar K. Characteristics of asthma and airway hyper-responsiveness after premature birth. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 16: 487–494, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamad AM, Clayton A, Islam B, Knox AJ. Guanylyl cyclases, nitric oxide, natriuretic peptides, and airway smooth muscle function. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 285: L973–L983, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartman WR, Smelter DF, Sathish V, Karass M, Kim S, Aravamudan B, Thompson MA, Amrani Y, Pandya HC, Martin RJ, Prakash YS, Pabelick CM. Oxygen dose responsiveness of human fetal airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303: L711–L719, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffmann LS, Schmidt PM, Keim Y, Schaefer S, Schmidt HH, Stasch JP. Distinct molecular requirements for activation or stabilization of soluble guanylyl cyclase upon haem oxidation-induced degradation. Br J Pharmacol 157: 781–795, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holditch-Davis D, Merrill P, Schwartz T, Scher M. Predictors of wheezing in prematurely born children. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 37: 262–273, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iben SC, Dreshaj IA, Farver CF, Haxhiu MA, Martin RJ. Role of endogenous nitric oxide in hyperoxia-induced airway hyperreactivity in maturing rats. J Appl Physiol (1985) 89: 1205–1212, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jobe AH. The new bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Curr Opin Pediatr 23: 167–172, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khassawneh MY, Dreshaj IA, Liu S, Chang CH, Haxhiu MA, Martin RJ. Endogenous nitric oxide modulates responses of tissue and airway resistance to vagal stimulation in piglets. J Appl Physiol (1985) 93: 450–456, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwinta P, Pietrzyk JJ. Preterm birth and respiratory disease in later life. Expert Rev Respir Med 4: 593–604, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lock JT, Sinkins WG, Schilling WP. Protein S-glutathionylation enhances Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release via the IP3 receptor in cultured aortic endothelial cells. J Physiol 590: 3431–3447, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin RJ, Prakash YS, Hibbs AM. Why do former preterm infants wheeze? J Pediatr 162: 443–444, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papapetropoulos A, Simoes DC, Xanthou G, Roussos C, Gratziou C. Soluble guanylyl cyclase expression is reduced in allergic asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 290: L179–L184, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez-Zoghbi JF, Bai Y, Sanderson MJ. Nitric oxide induces airway smooth muscle cell relaxation by decreasing the frequency of agonist-induced Ca2+ oscillations. J Gen Physiol 135: 247–259, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prakash YS. Airway smooth muscle in airway reactivity and remodeling: what have we learned? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 305: L912–L933, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rabe KF, Tenor H, Dent G, Schudt C, Liebig S, Magnussen H. Phosphodiesterase isozymes modulating inherent tone in human airways: identification and characterization. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 264: L458–L464, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sopi RB, Haxhiu MA, Martin RJ, Dreshaj IA, Kamath S, Zaidi SI. Disruption of NO-cGMP signaling by neonatal hyperoxia impairs relaxation of lung parenchyma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L1029–L1036, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stasch JP, Pacher P, Evgenov OV. Soluble guanylate cyclase as an emerging therapeutic target in cardiopulmonary disease. Circulation 123: 2263–2273, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stasch JP, Schmidt PM, Nedvetsky PI, Nedvetskaya TY, Arun Kumar HS, Meurer S, Deile M, Taye A, Knorr A, Lapp H, Müller H, Turgay Y, Rothkegel C, Tersteegen A, Kemp-Harper B, Müller-Esterl W, Schmidt HH. Targeting the heme-oxidized nitric oxide receptor for selective vasodilatation of diseased blood vessels. J Clin Invest 116: 2552–2561, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson MA, Britt RD Jr, Kuipers I, Stewart A, Thu J, Pandya HC, MacFarlane P, Pabelick CM, Martin RJ, Prakash YS. cAMP-mediated secretion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in developing airway smooth muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta 1853: 2506–2514, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toque HA, Monica FZ, Morganti RP, De Nucci G, Antunes E. Mechanisms of relaxant activity of the nitric oxide-independent soluble guanylyl cyclase stimulator BAY 41-2272 in rat tracheal smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol 645: 158–164, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H, Jafri A, Martin RJ, Nnanabu J, Farver C, Prakash YS, MacFarlane PM. Severity of neonatal hyperoxia determines structural and functional changes in developing mouse airway. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 307: L295–L301, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weissmann N, Lobo B, Pichl A, Parajuli N, Seimetz M, Puig-Pey R, Ferrer E, Peinado VI, Dominguez-Fandos D, Fysikopoulos A, Stasch JP, Ghofrani HA, Coll-Bonfill N, Frey R, Schermuly RT, Garcia-Lucio J, Blanco I, Bednorz M, Tura-Ceide O, Tadele E, Brandes RP, Grimminger J, Klepetko W, Jaksch P, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Seeger W, Grimminger F, Barbera JA. Stimulation of soluble guanylate cyclase prevents cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary hypertension and emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 189: 1359–1373, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang M, Kass DA. Phosphodiesterases and cardiac cGMP: evolving roles and controversies. Trends Pharmacol Sci 32: 360–365, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]