The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recognizes swimming as an excellent form of physical activity, with benefits of reducing risk for chronic diseases and improving mental health. However, aquatic facilities can pose a risk to public health from both illness and injury.

Although local and state public health codes typically regulate pools, spas and other aquatic venues, these codes may not always be based on up-to-date science, cover the newest construction developments in the aquatics field, or respond to new outbreak data such as those addressing spray pad-associated outbreaks or indoor air quality events. Lack of consistent health regulation in state and local codes not only confuses pool and spa owners, operators, suppliers and users, but also leaves persons unnecessarily vulnerable to disease and injury.

In recent years reported recreational waterborne disease outbreaks linked to aquatic facilities have steadily increased. Figure 1 illustrates this increase, which is driven largely by the challenges of maintaining an aquatic facility and preventing the transmission of a variety of ailments particularly diarrheal diseases.

Figure 1.

Recreational Waterborne Disease Outbreaks in Treated and Untreated Water

Additionally, aquatic venues are the sites for many injuries, particularly among children. Some of those injuries include the more common slips, falls, cuts, and bruises; others are life threatening, such as drowning, suction entrapment from pool drains, diving injuries and chemical injuries.

The Model Aquatic Health Code

In response to the increase in outbreaks of waterborne illness, in February 2005 CDC sponsored a workshop in Atlanta, Georgia, at which a variety of stakeholders made recommendations about how to improve public health outcomes in public aquatic facilities. A key recommendation was to develop a model aquatic health code that

was data driven,

addressed outbreaks, injuries, and other public health issues associated with aquatic facilities; and

was available for free for local and state jurisdictions to use to create their own codes.

Since the workshop, CDC units with expertise in environmental health, infectious disease, injury prevention, and public health law have collaborated on the MAHC effort. CDC worked with hundreds of volunteer stakeholders from public health, academia, and the aquatics industry, who have served on various technical committees, to compile the MAHC’s proposed code language and the supporting annex materials. A MAHC Steering Committee and CDC staff oversaw all committee work. This long-term project is now culminating with the MAHC launch planned for the summer of 2014.

CDC staff and Committee members have spent 2013 and the first part of 2014 responding to the thousands of public comments that were submitted during formal public comment periods on topical modules, as well as integrating these discrete modules into one cohesive document and making the document available for a final round of public comment. Once these final comments are addressed, the first edition of the Model Aquatic Health Code will be launched. The MAHC website (www.cdc.gov/mahc) provides MAHC provisions and explanatory annex materials with the public health rationale.

Operational Guidelines for the MAHC

Because the MAHC is not a federal law, it is enforceable only if state and local authorities adopt it. During the public comment period for the Regulatory Program module, some regulators recommended that code provisions for the regulatory community at the local and state levels should not be included in the MAHC. However, successful implementation of the MAHC would require improvements in all sectors of aquatic health including local and state inspection programs. To provide such guidance, CDC staff has moved these pool program operational guidelines out of the MAHC into separate stand-alone guidance to help supplement existing and in some cases new swimming pool inspection programs (Figure 2). The content for the Operational Guidelines follows a similar structure as that used in the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Annexes in their Model Food Code.

Figure 2.

Proposed MAHC Operational Guidelines

The Conference for the Model Aquatic Health Code (CMAHC)

Once the MAHC is fully launched and jurisdictions adopt the MAHC and begin to implement its provisions, questions and new research gaps will surface. Again learning from the FDA’s process, CDC and the National Conference of State Legislatures led the creation of an independent tax-exempt body called the Conference for the Model Aquatic Health Code (CMAHC) for updating the MAHC. This body will facilitate expert examination of new data and emerging issues, which in turn will prompt updates to the MAHC. CDC staff will maintain leadership through liaison and scientific review roles within the CMAHC.

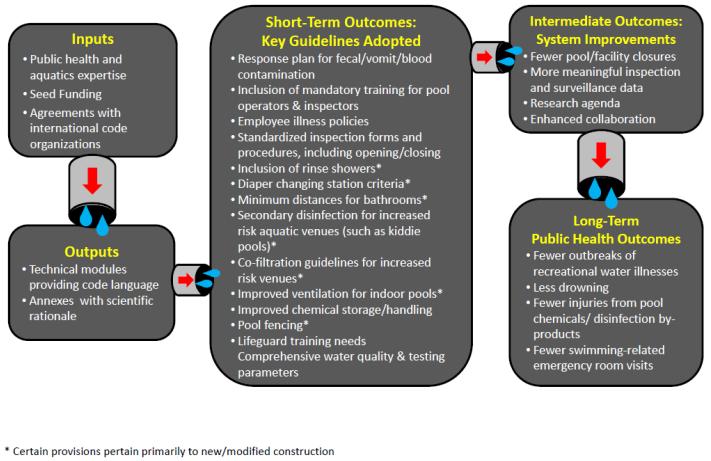

The MAHC process has been very labor intensive, but the use of the final product by local and state jurisdictions should eventually lead to fewer facility closures and reductions in waterborne disease outbreaks, drowning, and chemical injuries (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Model Aquatic Health Code Logic Model

Footnotes

Disclaimer in the standard Editor’s Note that will run with the column: The conclusions in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Hlavsa MC, Roberts VA, Kahler AM, Hilborn ED, Wade TJ, Backer LC, Yoder JS. Recreational Water–Associated Disease Outbreaks United States, 2009–2010. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63(1):6–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlavsa MC, Beach MJ. Healthy and Safe Swimming: Pool Chemical-Associated Health Events. Journal of Environmental Health. 2013;75(9):42–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake R, Peters J. Model Aquatic Health Code (MAHC) and the International Swimming Pool and Spa Code (ISPSC) Journal of Environmental Health. 2012;74(9):36–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Model Aquatic Health Code (MAHC): A National Model Swimming Pool and Spa Code. http://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/swimming/pools/mahc/