Abstract

Postural instability and resulting falls are major factors determining quality of life, morbidity, and mortality in individuals with Parkinson’s disease (PD). A better understanding of balance impairments would improve management of balance dysfunction and prevent falls in patients with PD. The effects of bradykinesia, rigidity, impaired proprioception, freezing of gait and attention on postural stability in patients with idiopathic PD have been well characterized in laboratory studies. The purpose of this review is to systematically summarize the types of balance impairments contributing to postural instability in people with PD.

Keywords: Balance, Posture, Parkinson’s disease, Falls, Management

INTRODUCTION

Postural instability, a key component of functional mobility, is often overlooked by both clinicians and their patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD), who focus on gait impairments. However, balance problems and resulting falls are major factors determining quality of life, morbidity, and mortality in individuals with PD [1-4]. According to a retrospective fall study of 489 in-patients admitted to a department of neurology, approximately 60% of PD patients had a history of at least one fall over the previous twelve months [4]. A recent meta-analysis and prospective studies also report considerably high fall incidences, even in optimally-medicated, early-stage PD (40–70%) [1,5,6]. From the results of epidemiologic studies, it is evident that balance dysfunction and related falls are common in individuals with PD, and the risk of falls increases gradually with disease progression without vigorous intervention to reduce the risk.

Balance can be defined as control of the body’s center of mass (CoM) over its base of support in order to achieve postural equilibrium and orientation [7]. Balance control requires active brain processes that integrate information from all levels of the nervous and musculoskeletal system, not only while moving (dynamic balance) but also while standing still (static balance). The basalganglia, a key pathologic structure in PD, is involved in control of balance via the thalamic-cortical-spinal loops and via the brainstem pedunculopontine nucleus and the reticulospinal system [8]. The basal ganglia is involved in controlling the flexibility of postural tone, scaling up the magnitude of postural movements, selecting postural strategies for environmental context (central set), and automatizing postural responses and gait [8-10]. Although subtle balance problems, such as increased postural sway jerkiness and slow turning, can be measured in PD even at the time of diagnosis, the severity and type of balance problems increases with disease progression [11,12].

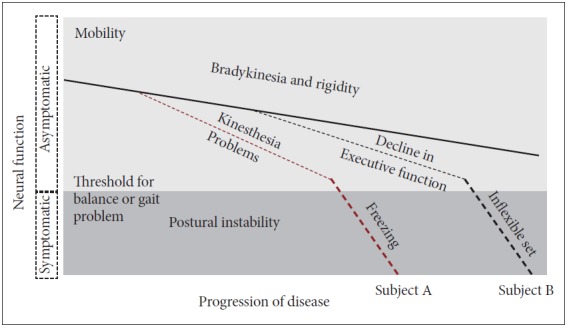

Although dopamine-sensitive bradykinesia and rigidity progressively affect balance and gait early in the disease, dopamine insensitive-balance problems increase later in the disease: impaired kinesthesia, inflexible postural set, lack of automaticity, and executive dysfunction. Each patient with PD eventually gets postural instability but the severity of each type of balance impairments may be very different. For example, Figure 1 shows declines in different types of balance control at different stages of disease for two different patients until each patient reaches a threshold of postural instability and frequent falls. The purpose of this review is to systematically summarize the types and underlying causes of balance impairments contributing to postural instability in people with PD. A better understanding of balance impairments would improve management of balance dysfunction and prevent falls in people with PD [13-17].

Figure 1.

Model for effects of progression of Parkinson’s disease (PD) on postural instability. All patients with idiopathic PD show progression of bradykinesia and rigidity that impairs postural control. However, later in the disease process, individual patients also show quite variable involvement of kinesthesia (proprioception), freezing of gait, decline of executive function and inflexible motor set that will result in a variety of types of mobility disorders among patients with PD.

RIGIDITY RESULTS IN BIOMECHANICAL IMPAIRMENTS

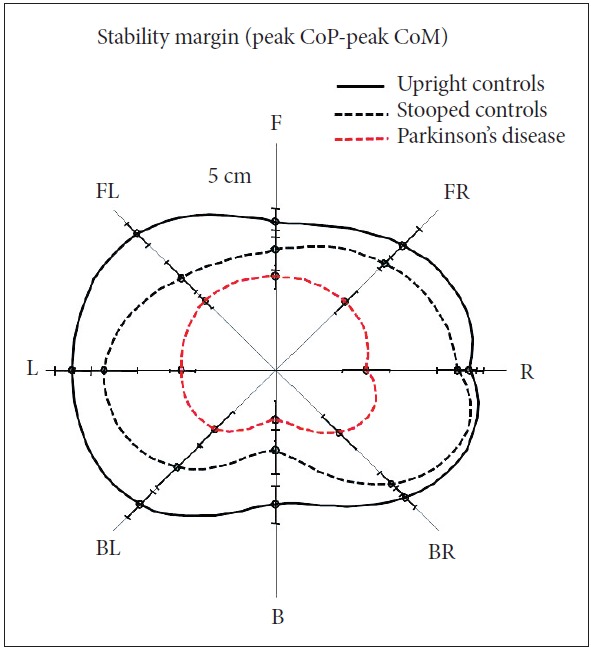

Excessive, inflexible axial postural tone, called rigidity, results in many biomechanical impairments affecting postural control such as abnormally stooped (flexed) postural alignment, forward head, Pisa syndrome, reduced joint range of motion, and low back pain. Stooped posture, due to excessive, static flexor muscle activity, is associated with increased velocity and jerkiness of postural sway in stance [18,19]. Automatic postural responses to external displacements are also impaired by a stooped postural alignment. The postural stability margin, which is defined by the difference in displacement of the center of pressure (CoP) under the feet and displacement of the body CoM in response to external perturbations, is reduced in healthy subjects who assume a stooped posture like PD (Figure 2) [19]. This observation suggests that a stooped posture, per se, has a destabilizing effect on postural control and is not an attempt to compensate for postural instability. Responses to backward body perturbations are especially compromised by a stooped posture, perhaps due to a shortening of the tibialis anterior muscle, which is critical for bringing the backward falling body back to equilibrium.

Figure 2.

Stooped (flexed) initial posture in healthy control subjects reduces postural stability margin (peak CoPpeak CoM) in response to multidirectional perturbations, especially backwards, like patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD). Stability margin was calculated in response to surface translations in 8 directions in 10 healthy control subjects standing upright and standing stooped and in 10 patients with PD who had a stooped posture. Adapted from Jacobs et al. [19]. CoM: center of mass, CoP: center of pressure, F: forward, FR: forward right, R: right, BR: backward right, B: backward, BL: backward left, L: left, FL: forward left.

Axial rigidity measured during standing is most excessive at the hip joints than at the trunk or neck [20]. The severity of axial rigidity has been shown to relate to impairments in turning and rolling [21]. An inflexible pattern of excessive postural tone and consequent reduced range of motion mechanically impedes the ability to execute postural reactions effectively. For example, rigidity is associated with cocontraction of muscles around joints in response to postural perturbations, rather than efficient postural synergies up one side of the body, making patients vulnerable to loss of balance and falls [9].

BRADYKINESIA IMPAIRS POSTURAL RESPONSES AND ANTICIPATORY POSTURAL ADJUSTMENTS

Automatic postural responses to unexpected external perturbations of the body’s CoM can be classified into feet-in-place and change-in-support strategies [22]. In patients with PD, both types of postural response strategies are smaller and slower (bradykinetic) than normal. Feet-in-place postural responses are slow to develop force with reduced scaling up for larger perturbations, often leading to displacement of the body CoM within base of support [9]. Interestingly, postural responses are even weaker with levodopa medication [9]. Patients with PD are also unable to quickly change postural muscle synergies with changes in initial support conditions, called inflexible “central set”, for example, standing versus-sitting posture, holding versus-free stance, surface translation versus-rotation, and voluntary resist versus-relax [23,24]. The difficultly adapting the pattern of muscle activation for changes in conditions may explain why it is difficult for patients with PD to benefit from assistive devices, such as canes and walkers, to improve stability.

Change-in-support strategies (for example, compensatory stepping or reaching) are also slowed and smaller due to bradykinesia [25]. Small compensatory stepping responses in response to external perturbations are larger when patients are provided a visual cue and can see their stepping leg [14]. However, when the stepping leg is not visible, the step to a visual target falls short, consistent with an increased visual dependence to overcome bradykinetic compensatory steps [14].

Patients who have freezing of gait also show freezing of their compensatory stepping responses to recover equilibrium, suggesting a common pathological neural pathway that leads to falls [23]. In addition, whereas healthy subjects quickly reach out with an arm to grab stationary objects to stabilize equilibrium in response to an external perturbation, patients with PD often bring their arms closer to their bodies [25].

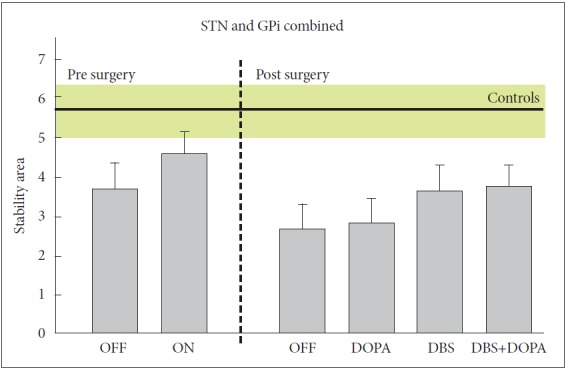

Unfortunately deep brain stimulation (DBS) does not improve bradykinetic postural responses. Six months after DBS in the subthalamic nucleus (STN), both feet-in-place and compensatory stepping responses are weaker than before surgery whether the stimulators are turned on or off, although turning the stimulator on improves postural responses slightly (Figure 3) [26]. DBS in the globus pallidus interna (GPi) did not improve or worsen postural responses [26]. A recent meta-analysis also showed that postural instability and gait difficulty subscores of the Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale were not maintained over time after surgery, particularly for STN DBS compared to GPi [27].

Figure 3.

Effects of DBS surgery and levodopa on postural stability in response to external perturbations. The DBS group means (SE) includes 14 patients with PD with stimulators in bilateral STN and 14 patients with stimulators in GPi and are compared to postural stability in 9 control subjects (mean and SE in green). Postural stability area is the difference between displacement of the center of pressure by postural response and displacement of the body center of mass following backward translations of the support surface. The smaller the stability areas, the worse the balance function. Adapted from St George et al. [26]. STN: subthalamic nucleus, GPi: globuspallidusinterna, OFF: unmedicated state, ON: best medicated state with dopaminergic drugs, OFF/OFF: DBS and medication both off, DOPA: medication on with DBS off (on/off), DBS: DBS on with medication off (off/on), ON/ON: DBS and medication both on.

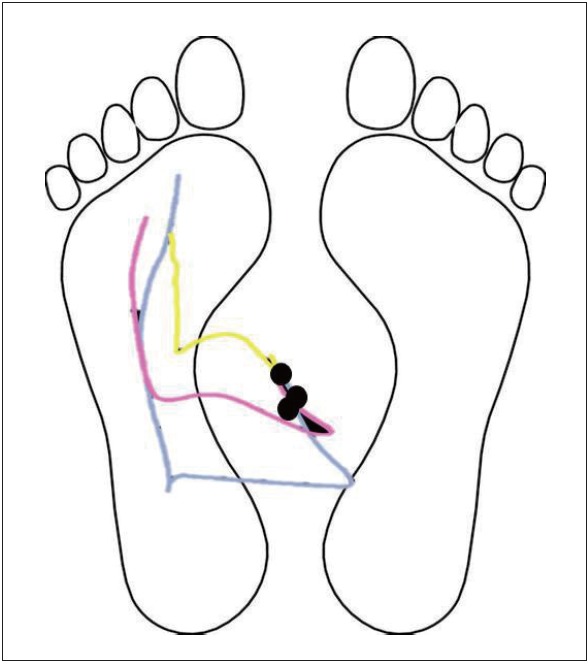

Like postural responses, anticipatory (or preparatory) postural adjustments (APAs) are bradykinetic. APAs are essential in maintaining postural equilibrium during self-initiated, voluntary movements such as: step-initiation, rise-to-toes, arm raising, or leg lifting. For example, normal step initiation is associated with a preparatory lateral shift of the body CoM toward the stance leg due to active displacement of the CoP toward the swing leg prior to lifting a foot off the ground. Patients with PD have smaller than normal APAs and are unable to scale up the size of APAs as needed with wider stance (Figure 4) [28]. The small size of the lateral APA weight shift prior to step initiation, results in start hesitation or akinetic freezing of gait, especially when initial stance width is wide. Bradykinetic APAs may explain why patients with PD tend to keep their feet close together as a narrow stance requires smaller APAs than a wide stance to initiate gait. Levodopa and external cues increase the size of APAs prior to step initiation, whereas DBS surgery, especially in the STN, reduces the size of APAs [29].

Figure 4.

Schematic comparing trajectories of center of pressure (CoP) prior to step initiation in healthy young, healthy elderly and patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD). Left is stance foot and right is step initiation foot. Black dots indicate initial CoP position over the base of support at the standing position. Yellow line is CoP displacement in a subject with PD, pink line CoP from a healthy elderly subject, and blue line from a healthy young subject.

IMPAIRED KINESTHESIA AFFECTS SENSORY INTEGRATION

Central sensory integration involves active interpretation of visual, vestibular and somatosensory inputs for orientation of the body in space. When sensory information is unavailable or conflicting, a process of sensory reweighting occurs so the nervous system ignores ambiguous, unhelpful information and relies more on useful sensory information. For example, somatosensory input normally contributes 70% to postural stability when standing on a firm surface with eyes open but, but vestibular input contributes 100% to postural stability when standing on an unstable surface with eyes closed [30]. Patients with advanced PD are often unable to stand on an unstable surface with eye closed, although their vestibular system is usually normal [31]. This finding suggests that patients with PD may take more time for the sensory reweighting process than healthy people. Another problem in sensory orientation is that the patients with PD have impaired use of proprioception for a kinesthetic body map. For example, patients with PD have difficulty perceiving small changes in surface inclination, i.e., impaired kinesthesia [32]. Consequently, a poor sense of kinesthesia in PD is compensated by an over-reliance on vision for postural orientation.

BRADYKINESIA AND FREEZING IMPAIR GAIT

Dynamic balance control involves controlling the body CoM with respect to, but not necessarily over a moving base of support. Walking becomes less automatic in PD so it requires more attention, particularly for challenging tasks such as turning, walking between obstacles, and dual-tasking. Newly diagnosed patients with PD show signs of bradykinetic gait features, such as reduced trunk rotation, decreased arm swing, and slow turns, even when walking speed is normal [11]. Extent of arm swing on the most involved side may, in fact, be the most sensitive early sign of gait affected by the disease. Bradykinesia results in slow gait velocity and shuffling of the feet that progresses with the disease. Freezing of gait is not usually only lack of stepping but often includes high frequency “trembling of the legs” as the patients attempt to get their feet moving. These quick motions may represent repeated, multiple APAs that get larger and larger until a step is finally triggered [33].

COGNITION-IMPAIRED ATTENTION

Many aspects of cognitive impairment in PD, such as altered attention, narrow cognitive focus, comorbid dementia, and fear of falls, could affect balance control. Normally, humans can walk efficiently with perfect balancing while thinking or carrying objects simultaneously, but people with PD often fail this dual-task walking. In fact, cognitive loading (i.e.; subtraction by Serial 7s) during gait affect most temporal and spatial gait measures in PD even more than age-matched control subjects [34,35]. The underlying mechanism is still unknown but it is assumed that basal ganglia may be responsible for making postural control “automatic” as it shifts from the cortical loop to brainstem loop. This automaticity of postural control, as measured by minimal change in balance and/or gait with a dual, cognitive task, may be a good measure of successful rehabilitation of imbalance in patients with PD.

CONCLUSION

Patients with PD show impairments in many aspects of postural control including: 1) rigidity affecting biomechanics, 2) bradykinesia of postural responses and anticipatory postural adjustments, 3) impaired kinesthesia for sensory integration, 4) bradykinetic gait with freezing, and 5) less automaticity of gait and balance. Unfortunately, levodopa and DBS often do not improve these postural impairments, so patients with PD need rehabilitation to improve balance and gait and prevent falls.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible with support from a grant from the National Institutes on Aging (AG006457) a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

OHSU and Dr. Horak have a significant financial interest in APDM, a company that may have a commercial interest in the results of this research and technology. This potential institutional and individual conflict has been reviewed and managed by OHSU.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kerr GK, Worringham CJ, Cole MH, Lacherez PF, Wood JM, Silburn PA. Predictors of future falls in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2010;75:116–124. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e7b688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahman S, Griffin HJ, Quinn NP, Jahanshahi M. Quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: the relative importance of the symptoms. Mov Disord. 2008;23:1428–1434. doi: 10.1002/mds.21667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams DR, Watt HC, Lees AJ. Predictors of falls and fractures in bradykinetic rigid syndromes: a retrospective study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:468–473. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.074070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stolze H, Klebe S, Zechlin C, Baecker C, Friege L, Deuschl G. Falls in frequent neurological diseases--prevalence, risk factors and aetiology. J Neurol. 2004;251:79–84. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pickering RM, Grimbergen YA, Rigney U, Ashburn A, Mazibrada G, Wood B, et al. A meta-analysis of six prospective studies of falling in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1892–1900. doi: 10.1002/mds.21598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloem BR, Grimbergen YA, Cramer M, Willemsen M, Zwinderman AH. Prospective assessment of falls in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2001;248:950–958. doi: 10.1007/s004150170047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacPherson JM, Horak FB. Posture. In: Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM, Siegelbaum SA, Hudspeth AJ, editors. Principles of neural science. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000. pp. 935–959. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takakusaki K, Habaguchi T, Ohtinata-Sugimoto J, Saitoh K, Sakamoto T. Basal ganglia efferents to the brainstem centers controlling postural muscle tone and locomotion: a new concept for understanding motor disorders in basal ganglia dysfunction. Neuroscience. 2003;119:293–308. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horak FB, Frank J, Nutt J. Effects of dopamine on postural control in parkinsonian subjects: scaling, set, and tone. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:2380–2396. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.6.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horak FB, Dimitrova D, Nutt JG. Direction-specific postural instability in subjects with Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2005;193:504–521. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zampieri C, Salarian A, Carlson-Kuhta P, Aminian K, Nutt JG, Horak FB. The instrumented timed up and go test: potential outcome measure for disease modifying therapies in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:171–176. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.173740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mancini M, Horak FB, Zampieri C, Carlson-Kuhta P, Nutt JG, Chiari L. Trunk accelerometry reveals postural instability in untreated Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson K, Dennison A, Roalf D, Noorigian J, Cianci H, Bunting-Perry L, et al. Falling risk factors in Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation. 2005;20:169–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs JV, Horak FB. Abnormal proprioceptive-motor integration contributes to hypometric postural responses of subjects with Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience. 2006;141:999–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maki BE, McIlroy WE. Control of rapid limb movements for balance recovery: age-related changes and implications for fall prevention. Age Ageing. 2006;35 Suppl 2:ii12–ii18. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King LA, Horak FB. Lateral stepping for postural correction in Parkinson’s disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:492–499. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horak FB. Postural orientation and equilibrium: what do we need to know about neural control of balance to prevent falls? Age Ageing. 2006;35 Suppl 2:ii7–ii11. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bloem BR, Beckley DJ, van Dijk JG. Are automatic postural responses in patients with Parkinson’s disease abnormal due to their stooped posture? Exp Brain Res. 1999;124:481–488. doi: 10.1007/s002210050644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs JV, Dimitrova DM, Nutt JG, Horak FB. Can stooped posture explain multidirectional postural instability in patients with Parkinson’s disease? Exp Brain Res. 2005;166:78–88. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-2346-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright WG, Gurfinkel VS, Nutt J, Horak FB, Cordo PJ. Axial hypertonicity in Parkinson’s disease: direct measurements of trunk and hip torque. Exp Neurol. 2007;208:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franzén E, Paquette C, Gurfinkel VS, Cordo PJ, Nutt JG, Horak FB. Reduced performance in balance, walking and turning tasks is associated with increased neck tone in Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2009;219:430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horak FB, Nashner LM. Central programming of postural movements: adaptation to altered support-surface configurations. J Neurophysiol. 1986;55:1369–1381. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.55.6.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chong RK, Horak FB, Woollacott MH. Parkinson’s disease impairs the ability to change set quickly. J Neurol Sci. 2000;175:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00277-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horak FB, Nutt JG, Nashner LM. Postural inflexibility in parkinsonian subjects. J Neurol Sci. 1992;111:46–58. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(92)90111-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carpenter MG, Allum JH, Honegger F, Adkin AL, Bloem BR. Postural abnormalities to multidirectional stance perturbations in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1245–1254. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.021147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.St George RJ, Carlson-Kuhta P, Nutt JG, Hogarth P, Burchiel KJ, Horak FB. The effect of deep brain stimulation randomized by site on balance in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2014;29:949–953. doi: 10.1002/mds.25831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.St George RJ, Nutt JG, Burchiel KJ, Horak FB. A meta-regression of the long-term effects of deep brain stimulation on balance and gait in PD. Neurology. 2010;75:1292–1299. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f61329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rocchi L, Chiari L, Mancini M, Carlson-Kuhta P, Gross A, Horak FB. Step initiation in Parkinson’s disease: influence of initial stance conditions. Neurosci Lett. 2006;406:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocchi L, Carlson-Kuhta P, Chiari L, Burchiel KJ, Hogarth P, Horak FB. Effects of deep brain stimulation in the subthalamic nucleus or globus pallidus internus on step initiation in Parkinson disease: laboratory investigation. J Neurosurg. 2012;117:1141–1149. doi: 10.3171/2012.8.JNS112006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cenciarini M, Peterka RJ. Stimulus-dependent changes in the vestibular contribution to human postural control. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:2733–2750. doi: 10.1152/jn.00856.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frenklach A, Louie S, Koop MM, Bronte-Stewart H. Excessive postural sway and the risk of falls at different stages of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24:377–385. doi: 10.1002/mds.22358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright WG, Gurfinkel VS, King LA, Nutt JG, Cordo PJ, Horak FB. Axial kinesthesia is impaired in Parkinson’s disease: effects of levodopa. Exp Neurol. 2010;225:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobs JV, Nutt JG, Carlson-Kuhta P, Stephens M, Horak FB. Knee trembling during freezing of gait represents multiple anticipatory postural adjustments. Exp Neurol. 2009;215:334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelly VE, Eusterbrock AJ, Shumway-Cook A. A review of dual-task walking deficits in people with Parkinson’s disease: motor and cognitive contributions, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Parkinsons Dis. 2012;2012:918719. doi: 10.1155/2012/918719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peterson DS, Fling BW, Mancini M, Cohen RG, Nutt JG, Horak FB. Dual-task interference and brain structural connectivity in people with Parkinson’s disease who freeze. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:786–792. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]