Abstract

Objectives

Antiretroviral (ARV) therapy has prolonged the life expectancy of HIV-infected persons, increasing their risk of age-associated diseases including atherosclerosis (AS). Decreased risk of AS has been associated with the prevention and control of hypertension (HTN). We conducted a cohort study of perimenopausal women and older men with or at-risk of HIV infection to identify risk factors for incident HTN.

Methods

Standardized interviews, physical examinations, and laboratory examinations were scheduled at 6-month intervals. Interview data included demographics, medical, family, sexual behavior, and drug use histories, and physical activity.

Results

There were 330 women and 329 men eligible persons; 27% and 35% of participants developed HTN during a median follow-up of 1080 and 1071 days, respectively. In gender-stratified analysis, adjusting for traditional HTN risk factors (age, race, BMI, smoking, diabetes, family history of HTN, alcohol dependence, physical activity, and high cholesterol), HIV infection was not associated with incident HTN in women or men [HR= 1.31, 95%CI (0.56, 3.06); HR = 1.67, 95%CI (0.75, 3.74), respectively]. Among HIV-infected women, although exposure to ARV's was not significantly associated with incident HTN [HR=0.72, 95%CI (0.26, 1.99)], CD4+ T-cell count was positively associated with incident HTN [HR=1.15 per 100 cells, 95%CI (1.03, 1.28)]. Among physically active HIV-infected men, exposure to ARV's was negatively associated with incident HTN [HR=0.15, 95%CI (0.03, 0.78)].

Conclusions

HIV infection was not associated with incident HTN in older men or women. This study provides additional evidence supporting a causal relationship between immune function and incident HTN, which warrants further study.

Keywords: hypertension, HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy, perimenopause, immunity, CD4+ T-cells

Introduction

Persons with HIV infection who have access to and are adherent with highly active antiretroviral therapy (ARV) are living longer. (1, 2) Because ARVs have prevented mortality from HIV-defining infections and cancers (3, 4), persons with HIV are now developing diseases associated with older age. Persons with HIV are now at risk of diseases caused by atherosclerosis including myocardial infarction and stroke. (5, 6) HIV infection is postulated to promote atherogenesis due to HIV-related chronic inflammation, even in those with suppressed viral load. (7) Some ARV agents appear to promote atherogenesis, in part due to effects on lipid metabolism. (8-12) Given the clear benefits of effective treatment for HIV infection, prevention of atherosclerotic disease must focus on modifiable risk factors by encouraging smoking cessation, weight control, physical activity, management of lipid abnormalities, and prevention and control of hypertension (HTN).

The risk of HTN in HIV-infected persons is not well understood due to a limited number of studies with conflicting results and design limitations. The prevalence of HTN in HIV-uninfected persons and HIV-infected, ARV-naïve persons has been compared in several cross-sectional studies. Of these, two found no difference in prevalent HTN (13, 14) and one found a negative association between HIV infection and prevalent systolic HTN. (15) The prevalence of HTN in ARV-naïve and ARV-experienced HIV-infected persons has also been compared in cross-sectional studies. Of these, one study found no difference in prevalent HTN (14) and two found a positive association between self-reported duration of ARV use and prevalent HTN. (13, 15)

Defining the epidemiology of HTN in HIV-infected persons is important for optimizing cardiovascular disease prevention strategies in this high risk population. Therefore, to better define the incidence of and risk factors for incident HTN in persons with HIV infection, we conducted a cohort study of perimenopausal women and older men with or at-risk of HIV infection.

Methods

Eligible persons for this study were participants in the MS cohort study or the CHAMPS cohort study. The MS cohort has been described in detail elsewhere. (16) Briefly, the cohort included perimenopausal women with or at risk of HIV infection, recruited in the Bronx, NY from September 2001 and followed through July 2006. “Perimenopausal” was defined as the absence of menses for at least three cycles, but no more than 11 during the past 12 months, and “at-risk of HIV infection” was defined as a history of unprotected sex with a homosexual or bisexual male, an injection drug user (IDU) male, or a male with HIV infection. Post-menopausal women were not included in this analysis. New-onset natural menopause was defined as the first visit following cessation of menses for at least 12 months that was not due to surgery, and new-onset surgical menopause was defined as cessation of menses due to hysterectomy and/or bilateral oophorectomy.

The CHAMPS cohort has been described in detail elsewhere. (17) Briefly, the cohort included men, age 49 years or older, with or at risk of HIV infection, also recruited in the Bronx, NY, from September 2001 and followed through July 2006. “At risk for HIV infection” was defined as a history of a) IDU, b) unprotected sex with a male, c) unprotected sex with a female known by the participant to have HIV infection, a history of IDU, or a history of unprotected sex with a homosexual or bisexual male with a history of IDU, d) five or more sexual partners in the last five years, or e) having exchanged sex for money or drugs.

Potential participants from both studies were screened after informed consent was obtained. Those who were eligible completed a baseline visit which included a standardized interview, physical examination, and blood draw. The standardized baseline interview included demographic information, medical history (with special emphasis on HIV-specific history, drug use history, and risk factors for cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis and fracture, and diabetes mellitus), medication history (including hormones, vitamins, HIV medications, methadone and medications for pain, HTN, diabetes mellitus, etc.), family medical history, sexual behavior, food intake, and physical activity. With the exception of some gender-specific modules (e.g. a menstrual calendar and questions about male-sex-with men), the standardized interview instruments, physical exams, and laboratory assays were identical in the two studies, performed by the same trained research personnel and completed in the same laboratories. The baseline physical exam included measurements of height, weight, waist circumference, and blood pressure. Blood was drawn to assess HIV status, HIV viral load, CD4+ T-cell count, CD4+ T-cell percentage, and hormone levels (testosterone for men; progesterone and estrogen for women). Participants were defined as having an “undetectable HIV viral load” when there were ≤ 75 copies/mL of HIV RNA. Participants were then scheduled for follow-up visits every 6 months. The follow-up visits included a comparable standardized interview, physical examination, and laboratory assays.

For the current analyses, perimenopausal women from the MS cohort and men from the CHAMPS cohort who were free of HTN at baseline were included. High blood pressure (HBP) was defined as systolic blood pressure > 140 or diastolic blood pressure > 90. HTN was defined was defined as 1) a history of HTN and HBP on examination, 2) history of HTN and current use of anti-hypertensive medications, or 3) two consecutive visits with measured HBP. For the third definition, the date of onset of HTN was considered to be at the first of those two visits.

The known risk factors for incident HTN that were included in the interview and defined as “traditional risk factors for HTN” in this study were age, black race, body mass index (BMI), pack-years of cigarette smoking, diabetes, family history of HTN, alcohol dependence, physical activity, and high cholesterol. To determine alcohol dependence, the “CAGE Questionnaire,” a brief screening test was administered to all participants.(18) Because answering “Yes” to two or more of the four questions is sensitive and specific for alcohol dependence across many different populations,(19) alcohol dependence was defined as a CAGE score ≥ 2. “Physically active” was defined as moderate or strenuous exercise for ≥ 20 minutes on > 1 day per week.

For this study, ARV-naïve is defined as persons who do not report any current or previous use of ARV's. ARV-experienced is defined as persons who report current and/or previous use of ARV's. The impact of ARV's on incident HTN is not known. Additionally, any impact of ARV's on incident HTN may occur during use and/or after use. The comparison groups were chosen with the assumption that the impact of ARV's on incident HTN endures after use. This is based on current theories about atherogenic disease in which a single irreversible insult to an arterial vessel initiates a disease process.

Statistical Analysis

Gender differences in demographic characteristics, risks factors for atherosclerotic disease, medical history, drug use history, and HIV-related history were examined using t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables, and chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables. Women and men were then analyzed separately to adjust for possible confounding and/or effect modification by gender.

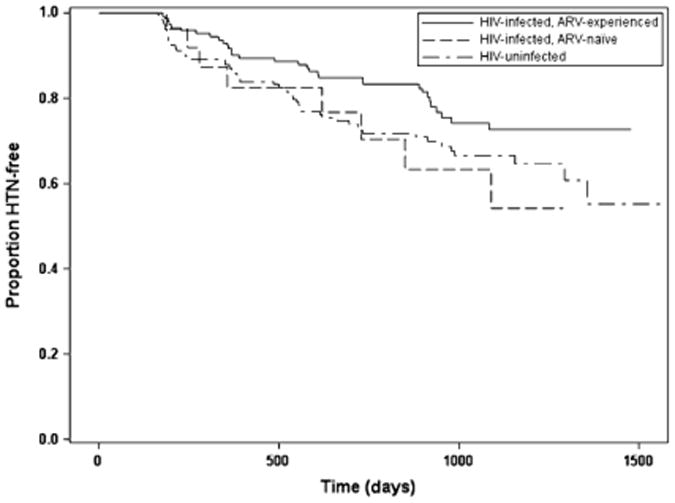

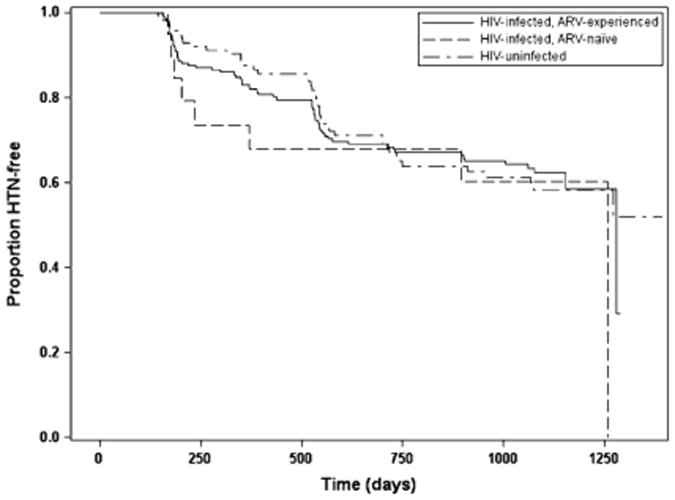

Gender-specific HTN-free survival curves for persons: 1) HIV-uninfected, 2) HIV-infected, ARV-naive, and 3) HIV-infected, ARV-experienced were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using log-rank tests.

Further analyses were designed to limit possible confounding and/or effect modification between HIV infection and ARV use. Participants with no history of ARV use, including HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected, were evaluated as a group to determine if HIV infection was associated with incident HTN. Participants with HIV infection, including ARV-naïve and ARV-experienced, were evaluated as a group to determine if ARV use was associated with incident HTN.

Among persons with no exposure to ARVs, Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess associations between the outcome variable, incident HTN, and possible risk factors for HTN. Risk factors examined included HIV infection, demographic characteristics (age, race, insurance status), co-morbid conditions (hyperthyroidism, angina, peripheral vascular disease, history of myocardial infarction, liver disease), family history of diabetes, history of drug use (use of any illicit drugs, use of any injecting drugs, use of cocaine, and use of heroin in the past 6 months and past 5 years), and new-onset menopause in women. The final Cox proportional hazards model included the outcome variable, incident HTN, and the exposure variables of HIV status, traditional risk factors for HTN (as defined above), and other characteristics found significantly associated with incident HTN in multivariable analysis. We evaluated the final models for all biologically plausible pairwise interactions among significant variables. Pairwise interactions found significant were included in a revised final model.

Among persons with HIV infection, Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess associations between the outcome variable, incident HTN, and possible risk factors for HTN. Risk factors examined included ARV naïve/experienced, demographic characteristics, co-morbid medical conditions, family history of diabetes, history of drug use, new-onset menopause in women, and markers of HIV status (CD4+ T-cell count, viral load, and undetectable/detectable status). The final Cox proportional hazards model included the outcome variable of incident HTN and the exposure variables of ARV naïve/experienced, traditional risk factors for HTN, and other characteristics found significantly associated with incident HTN in multivariable analysis. We evaluated the final models for all biologically plausible pairwise interactions among significant variables. Pairwise interactions found significant were included in a final revised model.

A P-value ≤ .05 was considered significant. The scale of continuous variables in the multivariable models was determined through martingale residual-based plots. All analyses were done use SAS Versions 9.1 and 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, North Carolina, USA). This study was approved by Institutional Review Boards of Mount Sinai School of Medicine and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Results

Of 619 women in the MS cohort, 242 (39%) had HTN and/or were postmenopausal at baseline. Of the 377 remaining women, 20 (5%) were missing critical data, 27 (7%) attended only one visit, and 330 (88%) were eligible for the study. Of the 643 men in the CHAMPS cohort, 253 (39%) men had HTN at baseline. Of the 390 remaining men, 11 (3%) were missing critical data, 50 (13%) attended only 1 visit, and 329 (84%) were eligible for the study. The median follow-up period of the eligible women was 1080 days (interquartile range (IQR) 882-1228). The median follow-up period of the eligible men was 1071 days (IQR 891-1092).

Baseline characteristics of men and women are shown in Table 1. The men were significantly older than the women by a mean of 11 years. Approximately one-half of the participants were black, and there were more women of Latino ethnicity compared to men. Approximately 80% of both groups received Medicaid and a minority had private insurance. Women had significantly higher BMIs, fewer pack-years of smoking, more hyperthyroidism history, and less prior injection of illicit drugs and recent cocaine use at baseline. Approximately two-thirds of men and one-half of women were HIV infected (P <.001). There were more men with ARV-experience. Among persons with HIV infection, men were significantly more likely to have previously used or currently be taking ARVs and to have lower CD4 counts.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants.

| Men N=329 (%) |

Women N=330 (%) |

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Data | |||||

| Mean Age (± SD) | 54.4 (± 4.43) | 43.4 (± 3.91) | <.001 | ||

| Race | <.001 | ||||

| Black | 167 (51) | 154 (47) | |||

| Latino | 83 (25) | 129 (39) | |||

| White | 54 (16) | 31 (9) | |||

| Other | 25 (8) | 16 (5) | |||

| Medicaid | 257 (78) | 264 (80) | .55 | ||

| Medicare | 86 (26) | 25 (8) | <.001 | ||

| Private Insurance | 48 (15) | 40 (12) | .36 | ||

| No insurance | 19 (6) | 26 (8) | |||

| Risk Factors for Atherosclerotic Disease | |||||

| BMI (mean, SD) | 25.5 (± 4.4) | 29.1 (± 6.8) | <.001 | ||

| Pack-years smoking (median, IQR) | 16.0 (IQR 5.0 – 32.5) | 12.0 (IQR 4.0-23.0) | <.001 | ||

| Diabetes† | 35 (11) | 30 (9) | .51 | ||

| Family History of HTN | 187 (57) | 194 (59) | .58 | ||

| CAGE score | .13 | ||||

| 0 | 135 (41) | 168 (51) | |||

| 1 | 41 (12) | 35 (11) | |||

| 2 | 53 (16) | 44 (13) | |||

| 3 | 51 (16) | 47 (14) | |||

| 4 | 49 (15) | 36 (11) | |||

| Physically active | 105 (32) | 74 (23) | .005 | ||

| High cholesterol† | 64 (20) | 56 (17) | .41 | ||

| Medical History | |||||

| Hyperthyroidism† | 8 (2) | 18 (6) | .04 | ||

| Peripheral Vascular Disease† | 3 (1) | 0 | .12* | ||

| Diagnosed with angina† | 3 (1) | 6 (2) | .51* | ||

| Previous heart attack† | 13 (4) | 8 (2) | .26 | ||

| Family history of diabetes | 124 (38) | 130 (40) | .63 | ||

| Drug Use History | |||||

| Ever used illicit drugs | 293 (89) | 298 (90) | .60 | ||

| Ever injected illicit drugs | 200 (61) | 124 (38) | <.001 | ||

| Cocaine use within 5 years | 168 (51) | 143 (43) | .05 | ||

| Cocaine use within 6 months | 100 (31) | 71 (22) | .008 | ||

| Heroin use within 5 years | 97 (29) | 89 (27) | .47 | ||

| Heroin use within 6 months | 54 (17) | 42 (13) | .17 | ||

| HIV-related History | |||||

| HIV-infected | 213 (65) | 171 (52) | <.001 | ||

| Ever exposed to ARV | 191 (90) | 145 (85) | <.001 | ||

| Currently taking ARV | 161 (76) | 120 (70) | .001 | ||

| CD4+ T-cell count+ | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 378 (242, 508) | 462 (330, 712) | <.001 | ||

| ≤ 50 | 8 (4) | 0 | .003 | ||

| 51 – 200 | 28 (16) | 17 (11) | |||

| 201 – 350 | 46 (26) | 26 (18) | |||

| 351 – 500 | 48 (27) | 39 (26) | |||

| > 500 | 50 (28) | 66 (45) | |||

| Viral load⌂ | |||||

| Median log 10 (IQR) | 2.57 (1.88 – 4.22) | 2.28 (1.88 – 3.72) | .05 | ||

| Undetectable | 84 (40) | 74 (43) | .47 | ||

| ≤ 500 | 109 (51) | 102 (60) | .15 | ||

| 501 – 10,000 | 40 (19) | 35 (20) | |||

| 10,001 – 50,000 | 36 (17) | 22 (13) | |||

| > 50,000 | 27 (13) | 12 (7) | |||

P-value determined using Fisher's Exact test

Data available for 180 men and 149 women

Data available for 212 men and 171 women

Based on self-report

Of the 330 eligible women, 90 (27%) developed HTN. The overall incidence of HTN was 140/1000 person-years among HIV-uninfected women [95%CI (100/1000 person-years, 180/1000 person-years)], 160/1000 person-years among HIV-infected, ARV-naïve women [95%CI (70/1000 person-years, 320/1000 person-years)], and 90/1000 among HIV-infected, ARV-experienced women [95%CI (60/1000 person-years, 130/1000 person-years)]. Of the 329 eligible men, 116 (35%) developed HTN. The overall incidence of HTN was 170/1000 person-years among HIV-uninfected men [95%CI (120/1000 person-years, 230/1000 person-years)], 220/1000 person-years among HIV-infected, ARV-naïve men [95%CI (90/1000 person-years, 430/1000 person-years)], and 170/1000 person-years among HIV-infected, ARV-experienced men [95%CI (130/1000 person-years, 210/1000 person-years)]. The Kaplan Meier analyses did not find significant differences between groups in incident HTN either among women (P = .13) (Figure 1) or men (P = .70). (Figure 2)

Fig. 1.

Time to incident hypertension among women. ARV, antiretroviral; HTN, hypertension.

Fig. 2.

Time to incident hypertension among men. ARV, antiretroviral; HTN, hypertension.

Results of multivariable analysis are shown in Table 2 for women and Table 3 for men. Among ARV-naïve women, HIV infection was not associated with incident HTN [hazard ratio (HR) 1.31, 95% confidence interval (CI) (0.56, 3.06); P = .54]. However, new-onset menopause [HR 2.73, 95%CI (1.04, 7.14), P = .04], BMI [HR 1.06, 95%CI (1.02, 1.10), P = .004], hyperthyroidism [HR 4.61, 95%CI (1.20, 17.68), P = .03] and cocaine use in the 6 months prior to baseline visit [HR 2.94, 95%CI (1.54, 5.62), P = .001] were positively associated with incident HTN.

Table 2. Cox-Proportional Hazards Models with incident HTN as the outcome among women‡.

| ARV-naïve: HIV-infected and - uninfected (N= 185) | HIV-infected: ARV-experienced and -naive (N=171) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR, 95% CI | P-value | HR, 95% CI | P-value | |

| HIV infection | 1.31 (0.56, 3.06) | .54 | ||

| New-onset menopause*† | 2.73 (1.04, 7.14) | .04 | 4.46 (1.72, 11.62) | .002 |

| Ever exposed to ARV | 0.72 (0.26, 1.98) | .52 | ||

| CD4+ T-Cell Count* (per 100 cells) | 1.15 (1.03, 1.28) | .01 | ||

| Age (continuous) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) | .80 | 0.95 (0.87, 1.05) | .29 |

| Black Race | 1.52 (0.84, 2.74) | .16 | 2.22 (1.05, 4.73) | .04 |

| BMI (continuous) | 1.06 (1.02, 1.10) | .004 | 1.11 (1.05, 1.17) | <.001 |

| Smoking pack-years | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | .77 | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | .32 |

| Diabetes† | 1.60 (0.65, 3.95) | .30 | 0.86 (0.26, 2.82) | .80 |

| Family history HTN | 1.29 (0.69, 2.42) | .42 | 1.12 (0.52, 2.42) | .77 |

| Alcohol dependence | 0.93 (0.52, 1.68) | .81 | 1.02 (0.51, 2.05) | .95 |

| Physically active | 1.63 (0.87, 3.07) | .13 | 1.05 (0.41, 2.69) | .91 |

| High cholesterol† | 1.69 (0.82, 3.48) | .15 | 0.66 (0.28, 1.56) | .34 |

| Hyperthyroidism† | 4.61 (1.20, 17.68) | .03 | ||

| Cocaine in last 6 months | 2.94 (1.54, 5.62) | .001 | ||

Three groups of women are included in the analyses above. HIV-uninfected (Group 1, N=159), HIV-infected/ARV-naïve (Group 2, N= 26), and HIV-infected/ARV-experienced (Group 3, N=145). The first analysis includes Groups 1 and 2 (N = 159 + 26 = 185). The second analysis includes Groups 2 and 3 (N= 26 + 145 = 171).

Analyzed as a time-dependent variable.

Based on self-report

Table 3. Cox-Proportional Hazards Models with incident HTN as the outcome among men.

| ARV- naïve: HIV-infected and -uninfected (N= 138) | HIV-infected: ARV- experienced and - naïve (N=213) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR, 95% CI | P-value | HR, 95% CI | P-value | |

| HIV infection | 1.67 (0.75, 3.74) | .21 | ||

| Ever exposed to ARV | 0.66 (0.30, 1.45) | .30 | ||

| CD4+ T-Cell Count* (per 100 cells) | 1.03 (0.94, 1.13) | .50 | ||

| Age (continuous) | 1.03 (0.96, 1.11) | .36 | 0.96 (0.90, 1.02) | .22 |

| Black Race | 1.23 (0.67, 2.23) | .50 | 2.34 (1.35, 4.05) | .002 |

| BMI (continuous) | 1.03 (0.96, 1.10) | .41 | 1.07 (1.00, 1.15) | .06 |

| Smoking pack-years | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | .03 | 1.01 (1.003, 1.02) | .008 |

| Diabetes† | 1.07 (0.39, 2.97) | .89 | 1.65 (0.79, 3.46) | .18 |

| Family history HTN | 2.60 (1.38, 4.91) | .003 | 1.61 (0.91, 2.84) | .10 |

| Alcohol dependence | 0.71 (0.38, 1.32) | .28 | 0.31 (0.16, 0.61) | <.001 |

| Physically active | 0.96 (0.51, 1.79) | .89 | 0.29 (0.12, 0.72) | .008 |

| High cholesterol† | 2.26 (1.09, 4.70) | .03 | 2.77 (1.50, 5.09) | .001 |

| Interaction of alcohol dependence and physical activity | 3.66 (1.08, 12.39) | <.04 | ||

| History of heart attack† | 4.24 (1.22, 14.74) | .02 | ||

| Family history of diabetes | 0.30 (0.17, 0.53) | <.001 | ||

Three groups of men are included in the analyses above. HIV-uninfected (Group 1, N = 116); HIV-infected/ARV-naïve (Group 2, N = 22); HIV-infected/ARV-experienced (Group 3, N=191). The first analysis includes Groups 1 and 2 (N = 116 + 22 = 138). The second analysis includes Groups 2 and 3 (N = 22 + 191 = 213).

Analyzed as a time-dependent variable.

Based on self report

Among HIV-infected women, ARV use was not associated with incident HTN [HR= 0.72, 95%CI (0.26, 1.98), P = .52]. New-onset menopause [HR 4.46, 95%CI (1.72, 11.62), P = .002], black race [HR 2.22, 95%CI (1.05, 4.73), P = .04], BMI [HR 1.11, 95%CI (1.05, 1.17), P < .001], and CD4+ T-cell count (per 100 cells) (HR 1.15, 95%CI (1.03, 1.28), P = .01) were positively associated with incident HTN.

Among ARV-naïve men, HIV infection was not associated with incident HTN [HR 1.67, 95%CI (0.75, 3.74), P = .21)]. Smoking pack-years [HR 1.01, 95% CI (1.00, 1.02), P = .03], family history of HTN [HR 2.60, 95%CI (1.38, 4.91), P = .003], high cholesterol [HR 2.26, 95%CI (1.09, 4.70), P = .03] and history of heart attack [HR 4.24, 95%CI (1.22, 14.74), P = .02] were positively associated with incident HTN.

The multivariable model among HIV-infected men included an interaction term between physical activity and alcohol dependence (Table 3). In the model, both physical activity [HR = 0.29, 95%CI (0.12, 0.72), p=.008] and alcohol dependence [HR = 0.31, 95%CI (0.16, 0.61), p=<.001)] were negatively associated with the risk of incident HTN. However, since there was a significant interaction between physical activity and alcohol dependence, the effects of alcohol dependence on the risk of incident HTN were modified by physical activity. To adjust for this effect modification, physically and non-physically active men were analyzed separately (Table 4).

Table 4. Cox-Proportional Hazards Models with incident HTN as the outcome among HIV+, ARV-experienced and -naïve men stratified by reported baseline physical activity‡.

| Physically active men (N= 68) | Non-physically active men (N= 141) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR, 95% CI | P-value | HR, 95% CI | P-value | |

| Ever exposed to ARV | 0.15 (0.03, 0.78) | .02 | 0.89 (0.33, 2.40) | .82 |

| CD4+ T-Cell Count* (per 100 cells) | 1.20 (0.80, 1.30) | .87 | 1.03 (0.93, 1.15) | .59 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.02 (.89, 1.17) | .78 | 0.94 (0.87, 1.02) | .17 |

| Black Race | 2.33 (o.67, 8.17) | .19 | 2.56 (1.34, 4.90) | .005 |

| BMI (continuous) | 1.16 (0.96, 1.39) | .12 | 1.43 (0.96, 1.13) | .32 |

| Smoking pack-years | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) | .81 | 1.02 (1.004, 1.03) | .006 |

| Diabetes† | 0.50 (0.05, 5.41) | .57 | 1.77 (0.79, 3.96) | .17 |

| Family history HTN | 1.53 (0.37, 6.29) | .56 | 1.35 (0.69, 2.66) | 0.38 |

| Alcohol dependence | 1.07 (0.34, 3.35) | .91 | 0.27 (0.13, 0.55) | <.001 |

| High cholesterol† | 1.24 (0.31, 4.99) | .76 | 4.16 (1.97, 8.77) | <.001 |

| Family history of diabetes | 0.34 (0.09, 1.29) | .11 | 0.28 (0.14, 0.55) | <.001 |

Analyzed as a time-dependent variable.

4 participants were missing data on physical activity

Based on self report

In physically-active, HIV-infected men, ARV experience was negatively associated with incident HTN [HR 0.15, 95%CI (0.03, 0.78), P=.02]. No other variables, including alcohol, were associated with incident HTN in this group.

In non-physically-active, HIV-infected men, ARV experience was not associated with incident HTN. Black race [HR 2.56, 95%CI (1.34, 4.90), P=.005), pack-years of smoking [HR 1.02, 95%CI (1.004, 1.03), P=.006], and high cholesterol [HR 4.16, 95%CI (1.97, 8.77), P < .001] were positively associated with incident HTN. Alcohol dependence [HR 0.27, 95% CI (0.13, 0.55), P<.001] and family history of diabetes [HR 0.27, 95%CI (0.14, 0.55), P<.001] were negatively associated with incident HTN.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of incident HTN in perimenopausal women and older men with or at-risk for HIV infection, HIV infection was not associated with incident HTN in either women or men. Higher CD4+ T-cell count was associated with incident HTN in HIV-infected, perimenopausal women. ARV use was associated with a decreased risk of incident HTN in men who were physically active at baseline. Characteristics traditionally associated with incident HTN in the general public (race, BMI, smoking, family history of HTN, alcohol dependence, physical activity, and high cholesterol) and characteristics associated with incident HTN in subsets of the population (cocaine use and new-onset menopause) were associated with incident HTN in this study as well.

The present prospective study found a significant association between higher CD4+ T-cell count and incident HTN in perimenopausal women. A report from the Women's Interagency Health Study (WIHS) cohort is the only published article in which we found prior evidence of such an association. Though data supporting this relationship is presented in a table in that study, the text does not comment on the association. (20) The study compared the prevalence of HTN and longitudinally collected exposure variables in 2059 HIV-positive women and 569 HIV-negative women. The multivariable analysis results showed that the risk of prevalent HTN was associated with higher CD4+ T-cell count after adjustment for age, race, education, BMI, pregnancy, smoking, injecting drug use, HIV status, and use of ARV.

Studies on renal function and HTN have found associations between T-cell lymphocytes and HTN, and thus lend support to the findings of the current study. One clinical study (21) suggested that proliferation of lymphocytes was required to maintain HTN. In that study, patients with HTN and normal renal function who received mycophenolate mofetil, an inhibitor of B- and T-cell lymphocyte proliferation for the treatment of psoriasis or rheumatoid arthritis, had a significant reduction in blood pressure.

Additional support suggesting an effect on HTN of T-lymphocytes comes from a sequential series of animal studies which demonstrated associations between HTN and the gland responsible for T-cell maturation (thymus), HTN and mature T-cells themselves, and HTN and IL-17, a T-cell produced cytokine. The first study found that in contrast to normal mice, nude mice with genetic aplasia of the thymus did not develop HTN when given desoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) and 1 per cent saline as drinking water for 21 days. (22) After receiving transplanted thymus tissue, the nude mice developed chronic HTN when given DOCA and 1 per cent saline. A later study found that RAG-1-/- mice, which lack both T and B cells, have blunted hypertensive responses to prolonged infusion of DOCA and saline. (23) Adoptive transfer of T cells, but not B cells, led to complete restoration of the hypertensive response to these stimuli. In studying HTN caused by angiotensin II, researchers found that the initial response to angiotension II was similar in IL-17-deficient and wild-type mice, but a sustained hypertensive response did not occur in IL-17-deficient mice.(24)

This study did not demonstrate a significant association between CD4+ T-cell count and incident HTN in men. There are several possible explanations. The directions and magnitudes of the HR's for CD4+ T-cell count in women and men are similar. It is possible that our sample size was too small to detect a significant association among men. Alternatively, pre-menopausal women may be immunologically different from men in ways that impacts HTN. It is possible that the well-known difference in risk for AS between pre-menopausal women and similarly-aged men is due at least in part to differences in immunologic function.

In the present study, in physically-active, HIV-infected men, traditional HTN risk factors were not associated with an increased risk of incident HTN. This finding concurs with current research on the pro-inflammatory effect of traditional risk factors for HTN and the anti-inflammatory effect of physical exercise. Such research suggests that traditional HTN risk factors release cytokines into the circulation which stimulate an inflammatory response leading to vascular damage and HTN. (25) In contrast, the prophylactic effect of being physically active on cardiac, metabolic, and oncologic disease is due to the creation of an anti-inflammatory milieu. Specifically, physical activity causes the release of “myokines” from the muscle fibers. The myokines lead to a cascade of anti-inflammatory cytokines. (26)

In physically-active, HIV-infected men, ARV experience was associated with a decreased risk of incident HTN. This finding may also be due to the anti-inflammatory effect of physical activity. Similar to traditional risk factors for HTN, current research suggests that HIV infection causes immune activation and inflammation through direct stimulation of the immune response and indirectly through reactivation of other viruses (e.g. cytomegalovirus), increased bacterial translocation, and altered gut permeability. (27) These inflammatory changes occur despite good HIV control (28-31) and lead to an increased risk of morbidity and mortality due to chronic diseases compared to the general population.(28, 32, 33) The anti-inflammatory effect of physical activity may decrease the inflammation due to HIV infection. ARVs in the absence of inflammation, may decrease the risk of incident HTN by decreasing viral load or by another yet-to-be identified mechanism.

The study results suggest that in the presence of physical activity, other traditional risk factors for incident HTN do not play a significant role in HIV-infected men. In contrast, in the absence of physical activity, black race, smoking, and high cholesterol increase the risk of incident HTN. Alcohol dependence and family history of diabetes were associated with a reduced risk of incident HTN. Physical activity is therefore an effect modifier for multiple variables. Although all pairs of statistically significant variables were checked for interaction, only the physical activity and alcohol dependence interaction term was statistically significant. Failure to find the other interaction terms significant may have been due to a lack of statistical power.

This study has several limitations. Kidney function has been associated with HIV status in some populations and is also associated with incident HTN. Unfortunately, data on kidney function was not collected in this study. However, impaired kidney function due to HIV infection would be expected to bias the results towards finding an association of HTN and HIV infection, which was not found. This study included persons within a narrow age range, and risk of incident HTN may vary by age. Finally, the maximum duration of follow-up in this study was 4.5 years. A longer period of study would likely include more cases of incident HTN and improve the precision of our findings.

The data in this study suggest that HIV infection is not associated with incident HTN in perimenopausal women and older men. Women and men with or at risk of HIV appear to have the same risk factors for HTN as the general population, and should be monitored similarly. This study provides additional evidence for a possible causal relationship between immune function and incident HTN, which warrants further study with the aim of improving treatment and prevention efforts.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA14998) and (R01DA13564)

Footnotes

Data presented previously at 48th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Disease Society of America in Toronto, Canada, in October 23, 2010.

References

- 1.UNAIDS OUTLOOK report. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palella FJ, Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998 Mar 26;338(13):853–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adih WK, Selik RM, Xiaohong H. Trends in Diseases Reported on US Death Certificates That Mentioned HIV Infection, 1996-2006. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2011 Jan-Feb;10(1):5–11. doi: 10.1177/1545109710384505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seligman SJ, Gross D. Trends in infectious disease and cancer in HIV infection. Annals of internal medicine. 1996 Nov 1;125(9):777. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-9-199611010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dube MP, Lipshultz SE, Fichtenbaum CJ, Greenberg R, Schecter AD, Fisher SD. Effects of HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy on the heart and vasculature. Circulation. 2008 Jul 8;118(2):e36–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.189625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giannarelli C, Klein RS, Badimon JJ. Cardiovascular implications of HIV-induced dyslipidemia. Atherosclerosis. 2010 Jun 13; doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mangili A, Polak JF, Quach LA, Gerrior J, Wanke CA. Markers of atherosclerosis and inflammation and mortality in patients with HIV infection. Atherosclerosis. 2011 Feb;214(2):468–73. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai S, Lai H, Celentano DD, Vlahov D, Ren S, Margolick J, et al. Factors associated with accelerated atherosclerosis in HIV-1-infected persons treated with protease inhibitors. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2003 May;17(5):211–9. doi: 10.1089/108729103321655863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpentier A, Patterson BW, Uffelman KD, Salit I, Lewis GF. Mechanism of highly active anti-retroviral therapy-induced hyperlipidemia in HIV-infected individuals. Atherosclerosis. 2005 Jan;178(1):165–72. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asztalos BF, Schaefer EJ, Horvath KV, Cox CE, Skinner S, Gerrior J, et al. Protease inhibitor-based HAART, HDL, and CHD-risk in HIV-infected patients. Atherosclerosis. 2006 Jan;184(1):72–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Saint Martin L, Vandhuick O, Guillo P, Bellein V, Bressollette L, Roudaut N, et al. Premature atherosclerosis in HIV positive patients and cumulated time of exposure to antiretroviral therapy (SHIVA study) Atherosclerosis. 2006 Apr;185(2):361–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duprez DA, Kuller LH, Tracy R, Otvos J, Cooper DA, Hoy J, et al. Lipoprotein particle subclasses, cardiovascular disease and HIV infection. Atherosclerosis. 2009 Dec;207(2):524–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baekken M, Os I, Sandvik L, Oektedalen O. Hypertension in an urban HIV-positive population compared with the general population: influence of combination antiretroviral therapy. Journal of hypertension. 2008 Nov;26(11):2126–33. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32830ef5fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jerico C, Knobel H, Montero M, Sorli ML, Guelar A, Gimeno JL, et al. Hypertension in HIV-infected patients: prevalence and related factors. American journal of hypertension. 2005 Nov;18(11):1396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seaberg EC, Munoz A, Lu M, Detels R, Margolick JB, Riddler SA, et al. Association between highly active antiretroviral therapy and hypertension in a large cohort of men followed from 1984 to 2003. AIDS (London, England) 2005 Jun 10;19(9):953–60. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000171410.76607.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller SA, Santoro N, Lo Y, Howard AA, Arnsten JH, Floris-Moore M, et al. Menopause symptoms in HIV-infected and drug-using women. Menopause (New York, NY. 2005 May-Jun;12(3):348–56. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000141981.88782.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein RS, Lo Y, Santoro N, Dobs AS. Androgen levels in older men who have or who are at risk of acquiring HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Dec 15;41(12):1794–803. doi: 10.1086/498311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P. The CAGE questionnaire: validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1974 Oct;131(10):1121–3. doi: 10.1176/ajp.131.10.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhalla S, Kopec JA. The CAGE questionnaire for alcohol misuse: a review of reliability and validity studies. Clin Invest Med. 2007;30(1):33–41. doi: 10.25011/cim.v30i1.447. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khalsa A, Karim R, Mack WJ, Minkoff H, Cohen M, Young M, et al. Correlates of prevalent hypertension in a large cohort of HIV-infected women: Women's Interagency HIV Study. AIDS (London, England) 2007 Nov 30;21(18):2539–41. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f15f7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrera J, Ferrebuz A, MacGregor EG, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Mycophenolate mofetil treatment improves hypertension in patients with psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006 Dec;17(12 Suppl 3):S218–25. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Svendsen UG. Evidence for an initial, thymus independent and a chronic, thymus dependent phase of DOCA and salt hypertension in mice. Acta pathologica et microbiologica Scandinavica. 1976 Nov;84(6):523–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1976.tb00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, et al. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007 Oct 1;204(10):2449–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madhur MS, Lob HE, McCann LA, Iwakura Y, Blinder Y, Guzik TJ, et al. Interleukin 17 promotes angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. Feb;55(2):500–7. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sprague AH, Khalil RA. Inflammatory cytokines in vascular dysfunction and vascular disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009 Sep 15;78(6):539–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen BK. Exercise-induced myokines and their role in chronic diseases. Brain Behav Immun. 2011 Jul;25(5):811–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Appay V, Sauce D. Immune activation and inflammation in HIV-1 infection: causes and consequences. J Pathol. 2008 Jan;214(2):231–41. doi: 10.1002/path.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandler NG, Wand H, Roque A, Law M, Nason MC, Nixon DE, et al. Plasma levels of soluble CD14 independently predict mortality in HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2011 Mar 15;203(6):780–90. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuller LH, Tracy R, Belloso W, De Wit S, Drummond F, Lane HC, et al. Inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers and mortality in patients with HIV infection. PLoS Med. 2008 Oct 21;5(10):e203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tien PC, Choi AI, Zolopa AR, Benson C, Tracy R, Scherzer R, et al. Inflammation and mortality in HIV-infected adults: analysis of the FRAM study cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Nov;55(3):316–22. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e66216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neuhaus J, Jacobs DR, Jr, Baker JV, Calmy A, Duprez D, La Rosa A, et al. Markers of inflammation, coagulation, and renal function are elevated in adults with HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2010 Jun 15;201(12):1788–95. doi: 10.1086/652749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaplan RC, Sinclair E, Landay AL, Lurain N, Sharrett AR, Gange SJ, et al. T cell activation and senescence predict subclinical carotid artery disease in HIV-infected women. J Infect Dis. 2011 Feb 15;203(4):452–63. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lyons JL, Uno H, Ancuta P, Kamat A, Moore DJ, Singer EJ, et al. Plasma sCD14 is a biomarker associated with impaired neurocognitive test performance in attention and learning domains in HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011 Aug 15;57(5):371–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182237e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]