Abstract

Background

Catheter-related bloodstream infections remain costly with no simple prevention. We report preliminary results of a phase I trial of ethanol-lock administration to prevent mediport catheter-related bloodstream infections in children.

Methods

Twelve patients receiving intravenous antibody treatments for neuroblastoma were enrolled. On 4 days of each 5-day antibody cycle, 70% ethanol was administered instead of heparin to dwell in each patient’s mediport overnight. We used clinical monitoring/questionnaires to assess symptoms; and measured blood ethanol levels and liver functions. Patients were tracked for positive blood cultures. Time-to-infection for ethanol-lock treated patients was compared with historical controls.

Results

We administered 123 ethanol-locks. No adverse symptoms attributable to ethanol occurred; one patient’s urticaria worsened. Blood ethanol levels averaged 11 mg/dL. The study was voluntarily suspended after 3 patients’ catheters became occluded, 1 of which fractured. A positive blood culture occurred in 1 of 12 patients (8%), but suspension of the study precluded statistical power to detect impact on time-to-infection.

Conclusions

Although children with mediport catheters exhibited nontoxic blood ethanol levels and a low rate of bloodstream infections following prophylactic ethanol-lock use, there was a high incidence of catheter occlusion. Adjustments are necessary before adopting ethanol-locks for routine prophylaxis against catheter infections in children.

Keywords: Ethanol-lock, Catheter-related bloodstream infection, Nosocomial infection, Central venous catheter, Mediport

Central venous catheter infections are now in the crosshairs in the debate about reimbursement for nosocomial infections. Hospital costs rise by over $39,000 for every episode of nosocomial bloodstream infection in pediatric intensive care unit patients [1]. Among pediatric oncology patients, catheter-related bloodstream infections represent more than half of all nosocomial infections [2], and continue to occur at rates of 22–25% in contemporary series of children treated for cancer using long-term central venous access devices [3, 4].

Recent strategies have been devised to address this problem, including the use of multi-point checklists for central line insertion and maintenance in hospital intensive care units [5], and the introduction of antibiotic flushes [6]. But no inexpensive, single-faceted strategy exists that averts the risk of development of resistant organisms while remaining easy to implement in a population of pediatric oncology patients, much of whose care is performed in the outpatient setting.

Ethanol has long been accepted as an intravenous antidote against poisoning with methylene glycol, the active ingredient found in antifreeze [7, 8]. In children with central venous catheters, ethanol-locking solutions (“ethanol-locks”) have been administered for purposes ranging from the clearance of luminal occlusions to the treatment of established, refractory, catheter-related bloodstream infections [9–11]. No study has examined the use of prophylactic ethanol-locks in pediatric oncology, nor directly measured the systemic absorption of ethanol following its use as a locking solution.

We undertook the first prospective phase I trial of ethanol-lock administration for the prevention of central venous catheter infections in pediatric oncology patients. The study was designed to demonstrate that the ethanol-lock strategy would be safe and well tolerated in the prophylactic setting. It was also designed to gather preliminary data on whether the ethanol-lock strategy reduces the occurrence of positive blood cultures in pediatric cancer patients with central venous catheters.

Methods

This prospective clinical trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and was registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT00471679). Informed consent was obtained from each participant or parent. Enrollment was limited to patients with high-risk neuroblastoma who were receiving protocol therapy [clinicaltrials.gov NCT00450307] with the 3F8 monoclonal antibody, which binds to the GD2 ganglioside of neuroblastoma cells [12]. To qualify for 3F8 treatment, patients must have already undergone treatments that had rendered them free of residual disease, or else had residual disease in bone marrow only. This population was selected because it represents a homogeneous group of patients who have completed cytotoxic chemotherapy and are not experiencing bouts of protracted neutropenia. Most of these children have long-term central venous access devices. Because the antibody treatment is conducted in a day hospital setting, central lines are accessed and deaccessed 5 days a week during protocol-specified treatment weeks, followed by a break of 2 to 4 weeks (with occasional extensions if human anti-mouse antibody titers preclude treatment), with repetition of such cycles for upwards of 6 months. During the years 2002–2005, we treated 145 neuroblastoma patients with surgically implanted central venous catheters (52 with mediports and 93 with tunneled Broviac-type catheters), using comparable 3F8 antibody protocols. These patients served as the historical control group.

Patients with tunneled (Broviac-type) external catheters, and those with implanted mediports with reservoirs, were eligible to enroll in the ethanol-lock study. We did not enroll anyone with a titanium port as we did not feel there was adequate preclinical data examining the interaction of ethanol with titanium. Protocol-specified exclusion criteria included age under 6 months; history of seizure disorder; serum bilirubin ≥ 1.5 times the upper limit of normal within the week before enrollment; serum AST, ALT, or alkaline phosphatase elevations ≥ 2.5 times the upper limit of normal within the week before enrollment; or the presence of prior infection in the central venous catheter to be treated.

This study was an open-label, single-armed study. Ethanol was obtained as 98% solution and diluted with sterile water in the pharmacy to obtain a 70% solution. This was then sterile filtered and dispensed in pre-filled, labeled syringes, in volumes corresponding to the filling volumes of each patient’s central venous catheter and reservoir. At the conclusion of the day’s scheduled 3F8 antibody therapy and before ethanol-lock administration, a 10-ml saline flush was given to clear residual solutes from the line. The ethanol-lock solution was then instilled into the catheter to dwell overnight. The external component of each catheter’s access tubing was labelled with a brightly colored sticker, in order to clearly signal to caregivers that ethanol dwelled in the line. Vital signs were monitored for one hour after each patient’s first exposure to the ethanol-lock, and for 15 minutes on each successive administration. Patients were then discharged from the day hospital with the ethanol dwelling in the catheter lumen.

A member of the study team withdrew the ethanol-lock solution from the catheter lumen the next morning and flushed the catheter with saline. If the ethanol-lock solution proved too sluggish to withdraw, all or part of it was flushed through followed by a saline flush. On the few occasions when a clinical event mandated use of the line before the next morning (e.g., a fever requiring the drawing of blood cultures through the central venous catheter), the ethanol-lock was withdrawn early to enable use of the central venous catheter.

Morning blood ethanol levels and liver function tests were obtained on each treatment week. Hepatotoxicity was graded according to the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE, version 3.0). Blood cultures were obtained only if indicated for clinical criteria (e.g., fever, rigors or clinical deterioration of the patient). In keeping with our established clinical practice for pediatric cancer patients, blood cultures were drawn from the central line and not peripherally. We felt a requirement to separately culture the central line and peripheral blood would have deterred families from enrolling in and complying with this study. As such, any positive blood culture drawn from the central venous catheter was construed as a study failure and resulted in removal of the patient from the study. Other off-study criteria defined in the protocol included seizures, pain resulting from the ethanol-lock, unremediable occlusion or failure of the central venous catheter, withdrawal of consent by the patient/parent, any grade 4 or higher toxicity attributable to ethanol-lock use, or termination of the patient’s participation in the 3F8 antibody treatment protocol. In the absence of these events, ethanol-lock treatments were continued during all scheduled treatment weeks for 6 months.

To evaluate the efficacy of ethanol-lock treatments in prolonging time-to-infection, we took each patient’s infection-free duration from the date of enrollment on the ethanol-lock study to the date of first positive blood culture, with censoring performed if protocol participation ended for other (non infection-related) reasons. For historical controls, time-to-infection was calculated as the duration during which each patient received 3F8 antibody protocol therapy through a central venous catheter until the date of the first positive blood culture. If there was not a positive blood culture, control patients were censored at either the date on which the patient ended antibody protocol therapy or on the date (if earlier) on which the central venous catheter was removed for an elective or noninfectious reason. Two patients whose central venous catheters were removed at outside institutions on unknown dates were censored at the latest date on which we could find confirmation in our medical records that the catheter was still in place.

Time-to-infection was estimated by Kaplan-Meier methods and differences between the control and treatment population determined by the log-rank test, with alpha=0.05 chosen to represent significance. The time-to-infection analysis was based upon the assumption that other reasons for coming off study, such as progression of disease, did not reflect an increase in the risk of infection.

Results

Central venous access devices

Although the study was open to patients with mediports as well as those with tunneled (Broviactype) catheters, all 12 of the enrolled patients had mediports. All were single-lumen Bard MRI implanted ports (Bard Access Systems, Inc., www.bardaccess.com) with plastic reservoirs and either silicone or polyurethane tubing. Sizes included 6.6 French (10 patients), 8 French (1 patient), and 9.6 French (1 patient).

Blood ethanol levels

Morning blood ethanol levels were sampled once from each patient each treatment week. The mean blood ethanol level was 11 mg/dL (range 0–79.5; n = 31 blood ethanol samplings). All readings were below the “legal limit” for ethanol intoxication (80 mg/dL). On half (52%) of all occasions, circulating ethanol was 0 mg/dL or below the limit of detection.

Catheter occlusion

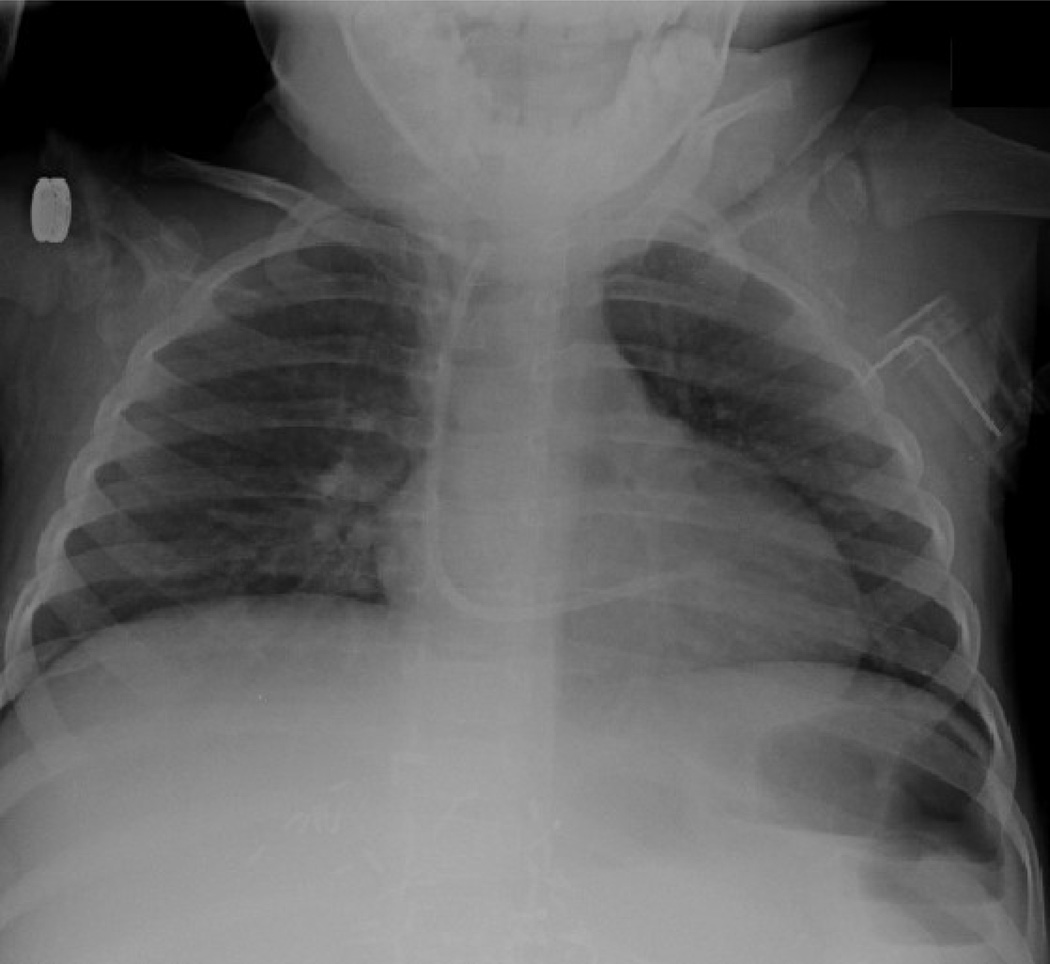

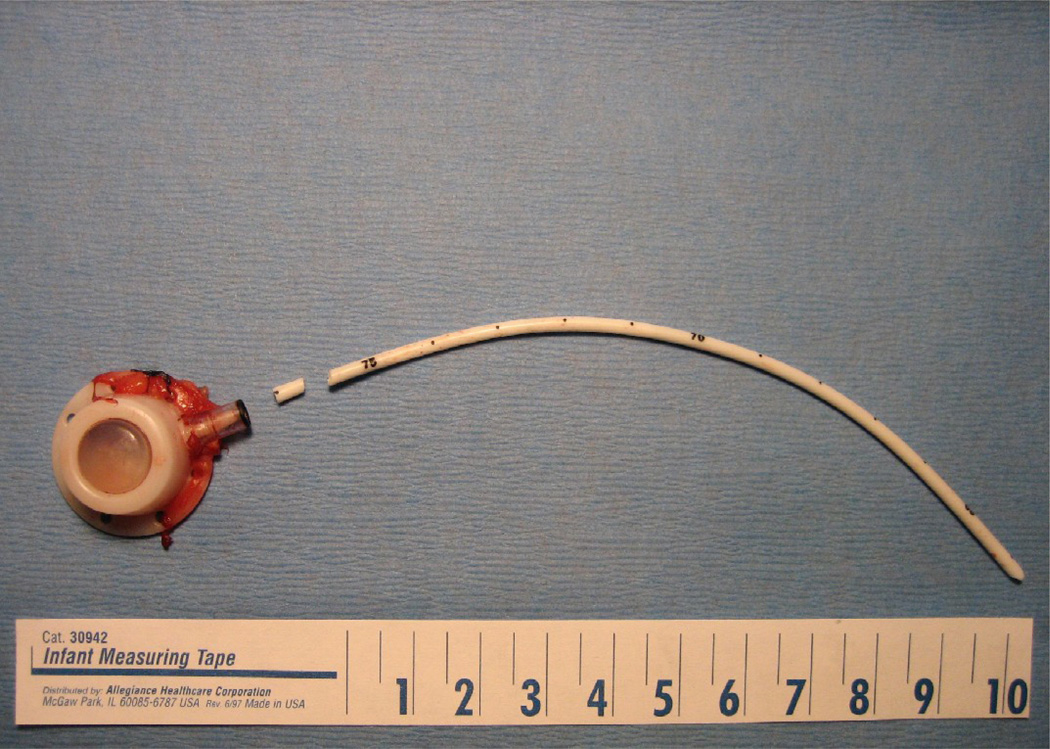

Three patients had irremediable occlusion of their mediports that occurred during ethanol-lock treatment weeks. One of these 3 patients also developed fracture and central embolization of the catheter (Fig. 1a, Fig. 1b). All 3 patients required surgical and/or angiographic removal of the central venous catheters. At explant, catheters in each of these cases contained dense thrombosis in device reservoirs or catheter lumens (Fig. 2a, Fig. 2b).

Fig. 1.

(a) Chest radiograph depicting left subclavian to right atrial mediport at initial insertion. (b) Same patient, after fracture of the mediport catheter from the subcutaneous reservoir. The catheter tubing has migrated to the right ventricle.

Fig. 2.

(a) Fractured mediport after explantation. (b) Lumen of fractured segment, filled with dense thrombus.

Hepatotoxicity

Two patients had no observed perturbations in their liver function tests. Transient increases in hepatic transaminases or alkaline phosphatase levels occurred at points during treatment in the remaining 10 patients. Grade 1 hepatotoxicity was seen in 7 patients, grade 2 in 1 patient, and grade 3 in 2 patients. One of the grade 3 hepatotoxicities was attributed to the initiation of total parenteral nutrition during an episode of adhesive small bowel obstruction. There was no grade 4 hepatotoxicity.

Clinical toxicity

Symptoms reported overnight after each of the 123 administrations of the ethanol-lock were selflimited and mild and included abdominal pain (n = 5 reported events), vomiting (n = 4), sneezing (n = 4), slurred speech (n = 3), sleepiness (n = 3), puffiness of the cheeks (n = 3), change in personality (n = 2), and pain on inspiration (n = 1). These are typical side effects of opioids and antihistamines given to counter side effects of 3F8 antibody administration, and could not specifically be attributed to ethanol-lock use.

One patient developed grade 2 cutaneous urticaria related to 3F8 antibody administration, which is also common, and subsequently received antihistamines followed by placement of the day’s scheduled ethanol-lock. Her urticaria worsened after ethanol administration. She was removed from study.

Reasons for ending study participation

Table 1 summarizes the reasons for ending study participation. Of the 12 patients, 4 completed a full 6 months on study. Three were removed following catheter occlusion. Two suffered progression of neuroblastoma and were removed from 3F8 antibody treatment; on this basis, they no longer qualified for ethanol-lock placement. One patient was removed from study after a positive blood culture occurred, and 1 removed following exacerbation of antibody-related urticaria, as previously described. One patient’s consent was withdrawn by the parents, who stated that the extra time and effort involved in receiving the ethanol-lock therapy added to the length of their outpatient visits for antibody therapy.

Table 1.

Reasons for Ending Study Participation

| Off-study reason | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Completed 6 months of ethanol-lock study | 4 |

| Catheter thrombosis | 3 |

| Progression of neuroblastoma | 2 |

| Positive blood culture | 1 |

| Parental preference | 1 |

| Exacerbation of antibody-related urticaria | 1 |

Infection

A positive blood culture occurred in only 1 of 12 patients (8%) on study. The positive blood culture was for Streptococcus pneumoniae, and happened during a hospitalization for pneumonia.

Among historical controls, positive blood cultures occurred in 32 of 145 patients (22%) during up to 6 months of similar 3F8 treatment through an implanted central venous catheter and 10 of 52 (19%) in the subset of historical controls with mediports. Due to the low number of infectious events in both groups, the median time-to-infection was not reached in either the ethanol-lock group or the historical control group. Given the premature suspension of the study and resulting small sample size, we were underpowered to detect any significant difference in time-to-infection between the groups (data not shown).

Discussion

The occurrence of thrombosis in 2 cases, and thrombosis followed by fracture and central embolization of a mediport catheter in a third case, led to the voluntary suspension of this study by the investigators. Ex vivo examination of the 3 explanted catheters indicated that the primary event in all 3 cases was intraluminal catheter thrombosis. We believed catheter fracture to be a secondary event after we attempted to flush the line in the face of obstruction. Erosion of the catheter material did not appear to be the primary problem, which supported existing preclinical data that has found no deterioration in the integrity or electron-micrographic appearance of silicone or polyurethane catheters after several weeks of continuous ethanol exposure [13, 14]. None of the study patients had a history of prothrombotic state or prior catheter thromboses.

We suspect residual serum or therapeutic medications may have been present in the catheter reservoirs, leading to denaturation, precipitation, and occlusion of the lumens—despite administration of a generous saline flush before ethanol-lock placement. It may be important that all 12 of the enrolled patients had implanted mediports with subcutaneous reservoirs, unlike previously-reported studies of ethanol-lock therapy in children, in which most had Broviac catheters that lack reservoirs [9, 10]. Alternatively, it is possible that the catheter thromboses were related to the absence of heparin, rather than the presence of ethanol. Cesaro et al. reported that 82% of pediatric cancer patients receiving saline locks through a positive pressure cap on their Broviac or Hickman catheters had episodes of occlusion, compared with 40% of those receiving heparin flushed through a standard cap—a statistically significant difference—with most episodes clearing after infusion of urokinase [15].

Secondary endpoints in this study revolved around a reduction in infection rates. Despite the occurrence of catheter-related adverse events, the rate of bloodstream infections was surprisingly low. Only 1 positive blood culture occurred among any of the 12 patients while on-study, with a median follow-up time (time to end of study participation or line removal, whichever occurred first) of 16 weeks. While historically the most common organisms recovered from central venous catheter cultures at our institution are staphylococcal, the organism recovered from the solitary study patient with a positive blood culture was Streptococcus pneumoniae, the culture drawn during a hospital admission for pneumonia. Thus, while our protocol construed any positive blood culture as a stopping point for patients on this trial, this particular blood culture may have reflected hematogenous dissemination from the lungs rather than a classic catheter-related bloodstream infection. Owing to the early suspension of the trial and early removal of several catheters, we were underpowered to detect any statistically significant difference in infection rates versus historical controls.

Despite these issues, exposure of children to 70% ethanol as an indwelling catheter-lock was clinically well tolerated. Observed symptoms such as vomiting and sleepiness were rare and were indistinguishable from the typical symptoms that occur following opioids and antihistamines given with administration of the 3F8 antibody. Although perhaps not reflective of true peak exposure to ethanol, morning blood ethanol levels were undetectable more than half of the time, and were below the “legal limit” of intoxication on the remaining occasions. We did note the occurrence of grade 3 liver function test elevation in two ethanol-lock-treated patients. One of these patients exhibited the toxicity immediately after initiation of parenteral nutrition during a bowel obstruction, but in the second case the hepatotoxicity could not be easily ascribed to anything other than exposure to ethanol-lock treatments. A previous study using ethanol-locks for treatment of established infections also noted the appearance of low-grade hepatotoxicity [9], and this should therefore be considered a possible side effect of ethanol-lock administration. However, we did not observe any grade 4 liver toxicity. Likewise, no neurologic disturbances or seizures were noted. The relative lack of serious systemic side effects seen in this study accords with literature that has demonstrated successful administration of intravenous ethanol to children as an antidote to methylene glycol poisoning, at doses several times higher than the maximal ethanol doses used in the present study [16].

Conclusions

Ethanol-lock treatment of mediports in pediatric patients appears to be physiologically well tolerated and, in prophylactic use, is potentially associated with a low rate of catheter-related bloodstream infection. However, the occurrence of 3 serious catheter-related adverse events in the 12 patients enrolled on this trial clearly indicates that adjustments are needed before adopting the ethanol-lock strategy for prophylactic use. We believe further use of the prophylactic ethanol-lock strategy should be predicated upon changes in the concentration or dwell time of ethanol or preceded by studies on its compatibility with heparin, citrate, or other anticoagulants.

Acknowledgments

Support for this study was provided by a grant from the Society of Memorial Sloan-Kettering.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

This study was presented at the 40th annual meeting of the American Pediatric Surgical Association, Fajardo, Puerto Rico, May 2009.

References

- 1.Elward AM, Hollenbeak CS, Warren DK, et al. Attributable cost of nosocomial primary bloodstream infection in pediatric intensive care unit patients. Pediatrics. 2005;115:868–872. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon A, Fleischhack G, Hasan C, et al. Surveillance for nosocomial and central line-related infections among pediatric hematology-oncology patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21:592–596. doi: 10.1086/501809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fratino G, Molinari AC, Parodi S, et al. Central venous catheter-related complications in children with oncologic/hematological diseases: an observational study of 418 devices. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:648–654. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Journeycake JA, Buchanan GR. Catheter-related deep venous thrombosis and other catheter complications in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4575–4580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.5343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2725–2732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henrickson KJ, Axtell RA, Hoover SM, et al. Prevention of central venous catheter-related infections and thrombotic events in immunocompromised children by the use of vancomycin/ciprofloxacin/heparin flush solution: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind trial. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1269–1278. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.6.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barceloux DB, Krenzelok EP, Olson K, et al. American Academy of Clinical Toxicology practice guidelines on the treatment of ethylene glycol poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1999;37:537–560. doi: 10.1081/clt-100102445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wacker WEC, Haynes H, Druyan R, et al. Treatment of ethylene glycol poisoning with ethyl alcohol. JAMA. 1965;194:1231–1233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dannenberg C, Bierbach U, Rothe A, et al. Ethanol-lock technique in the treatment of bloodstream infections in pediatric oncology patients with Broviac catheter. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:616–621. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200308000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Onland W, Shin CE, Fustar S, et al. Ethanol-lock technique for persistent bacteremia of long-term intravascular devices in pediatric patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:1049–1053. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.10.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Werlin SL, Lausten T, Jessen S, et al. Treatment of central venous catheter occlusions with ethanol and hydrochloric acid. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1995;19:416–418. doi: 10.1177/0148607195019005416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung NKV, Kushner BH, Cheung IY, et al. AntiGD2 antibody treatment of minimal residual stage 4 neuroblastoma diagnosed at more than 1 year of age. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3053–3060. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crnich CJ, Halfmann JA, Crone WC, et al. The effects of prolonged ethanol exposure on the mechanical properties of polyurethane and silicone catheters used for intravascular access. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26:708–714. doi: 10.1086/502607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McHugh GJ, Wild DJC, Havill JH. Polyurethane central venous catheters, hydrochloric acid and 70% ethanol: a safety evaluation. Anaesth Intens Care. 1997;25:350–353. doi: 10.1177/0310057X9702500404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cesaro S, Tridello G, Cavaliere M, et al. Prospective, randomized trial of two different modalities of flushing central venous catheters in pediatric patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2059–2065. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.4860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caravati EM, Heileson HL, Jones M. Treatment of severe pediatric ethylene glycol intoxication without hemodialysis. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2004;42:255–259. doi: 10.1081/clt-120037424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]