Abstract

The susceptibility of the developmental stages of rust-red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum to a range of concentrations of phosphine over varying durations from 24 to 168 h was reconnoitered in the laboratory at 25 ± 2 °C. Responses of the life stages exposed to phosphine were compared with those of un-treated controls over 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144 and 168 h exposures and mortality was assessed after 14 days. Among the life stages tested, pupae were more tolerant to phosphine followed by the egg and the larval instars. At 24 h, the maximum LC50 value was observed in case of egg; 1.571 mgL−1; followed by the pupae, 6th instar, 4th instar and 2nd instar larvae with LC50 values of 1.184, 0.336, 0.212 and 0.081 mgL−1 respectively. However, continued exposure of the developmental stages to phosphine, recorded maximum LC values in the pupae followed by egg and the larval instars. A linear increase in the mortality response was witnessed in all the insect stages when the exposure periods were extended from 24 to 168 h with increasing concentrations of phosphine, conversely significant increase in mortality was greatly apparent during the initial treatment periods.

Keywords: Phosphine, Tribolium castaneum, Developmental stages, Exposure period, Toxicity

Introduction

Stored food commodities are often prone to attack by a variety of insect pests resulting in qualitative and quantitative losses. The damage to stored food products caused by insects accounts for about 5–10 % in the temperate regions of the world and 20–30 % in the tropical countries (Rajashekar et al. 2010; Nakakita 1998). Management of these stored product insect pests mainly involves the use of synthetic pesticides in the form of fumigants and as residual contact insecticides (Devi and Devi 2013; Jaya et al. 2012; Pandey et al. 2012). Fumigation is one such technique administered at the storage level to eradicate the pest population effectively (Homayouni et al. 2014); well known for its rapid toxicity and no/less residual effect on end use products. However, botanical formulations are well known for their insecticidal activity, repellence to pest, contact toxicity and fumigation effects (Kedia et al. 2013), their applicability to large scale fumigation is still uncertain. Phosphine is the major and widely used fumigant for the control of insect pests in various stored food commodities world over (Rajashekar et al. 2012) and has replaced many liquid fumigants, ethylene dichloride-carbon tetrachloride mixture and mixtures containing ethylene dibromide. In India, from the total production of 2500 MT of aluminium phosphide formulations, about 80 % is used for the protection of stored products; (Rajendran and Narasimhan 1994) indicating the dependency of stored product insect pest management on phosphine. Insect survival is an emerging problem particularly in large-scale phosphine fumigation of commodities attributed mainly by reduction in the treatment period and/or due to its poor toxicity on the tolerant egg and pupae of insect pests. The higher tolerance of both the eggs and pupae to phosphine at least partially has been attributed to the lower uptake of phosphine compared to larvae and adults. In general, a compromise in the exposure period is not entitled thereby increase in phosphine dose as the action on insects is known to be slow. In addition to this, it was reported that for phosphine toxicity, time period is considered imperative both as a dosage factor and as a response factor (Winks 1986). A minimum of 5–7 days of exposure has been suggested for the effective PH3 fumigation carried at 25 °C. For complete eradication of insects at lower temperatures, still longer exposures are required than the prescribed one (AFHB/ACIAR 1989). The evolution of phosphine resistance among the insect pest population asserts the need of increasing the exposure time further to control resistant populations. For instance it was 7 days (Taylor and Harris 1994; Bengston et al. 1997; Rajendran and Muralidharan 2001), later 8 days (Rajendran and Gunasekaran 2002; Collins et al. 2005), 6–9 days (Price and Mills 1988; Liang et al. 1999; Collins et al. 2002) and more than 7 days (Sayaboc et al. 1998) for phosphine-resistant Rhyzopertha dominica. The differences between the age-groups of the tolerant stages are extremely higher for phosphine fumigant (Howe 1973). The degree of tolerance to phosphine varies between the insect stages, especially known to alter during the developmental period of the pre–adult stages. In addition, it has been reported that the change in tolerance to phosphine in both the egg and pupal stage during their development is hasty and large (Lindgren and Vincent 1966; Nakakita and Winks 1981). Phosphine is more effective on the more susceptible stages of first instar larva and the adults, while high levels of kill can be expected in the tolerant stages, provided an adequate concentration is maintained for a period long enough for eggs to reach late egg stage or hatch, or for pupae to reach late pupal stage or moult to adults (Winks 1986).

Hence there is a strict need for standardizing appropriate dosage with respect to the insect stage and the time factor for achieving the wholesome insecticidal potency of phosphine. In this context, the present study was undertaken to examine the effect of extended exposure periods on the mortality of the developmental stages of T.castaneum, a common stored product insect. Toxicity tests were conducted on eggs (0–1 day old), early 2nd instar (2–3 days old), mid 4th instar (8–9 days old) and late 6th instar (14–15 days old) larvae and pupae (1–3 days old).

Materials and methods

Insect culture

Culture of Tribolium castaneum (laboratory strain) was initiated from adults isolated from stock culture and reared on whole-wheat flour supplemented with 5 % powdered yeast (FAO 1975). The insect cultures were maintained in the laboratory at 30 ± 2 0 C and 70 ± 5 % R.H. in a temperature humidity controlled chamber.

Collection of eggs

In order to obtain eggs of T. castaneum, 250 g of wheat flour sieved 5–6 times using 85-mesh standard sieves (180 μm pore size) was taken in a separate glass bottle (500 ml) and about 1000 T. castaneum adults of mixed age and sex were released onto it. After 24 h, the adults were separated by sieving the wheat flour with a 25-mesh sieve (600 μm pore size). The eggs were then separated from the flour by sifting through 85-mesh sieve.

Collection of larvae

To obtain larval instars, after 3 days the adults were removed using 85 mesh size sieve, retaining the culture contents on to the same bottle and were incubated at 30 ± 2 °C and 70 ± 5 % R.H. held inside a temperature humidity controlled cabinet. On the 5th d, the culture contents were spread across Whatmanns filter paper circles of 15 cm diameter to collect 2nd instar larvae adhered to the filter circles. After collecting adequate number of 2nd instar larvae for the toxicity studies, the culture contents were held back in the same culture bottle and were incubated at 30 ± 2 °C and 70 ± 5 % RH. For the collection of 4th and 6th instar larvae, the culture contents were sifted using a 600 μm pore size sieve on 6th and 12th day respectively.

Collection of pupae

To obtain pupae for the toxicity tests, after 3 days the adults were removed using the 85 mesh size sieve, retaining the culture contents on to the same bottle and incubated at 30 ± 2 °C and 70 ± 5 % R.H. inside a temperature/humidity controlled cabinet. After 20 day, the contents were sifted using a 600 μm pore size sieve and pupae which remained on the surface of the sieve were collected.

Generation of phosphine gas

Phosphine gas was generated in a gas burette using commercial formulation of aluminium phosphide tablet suspended in 5 % sulphuric acid solution (FAO 1975). For dosing, the required volume of gas was drawn from the gas burette using a gas-tight syringe, and injected into desiccators through the self sealing septum in the lid of desiccators which were used as test chambers for exposing the life stages of insects.

Toxicity studies on eggs

Polystyrene microtiter plates of 12 cm × 8 cm size were cut into two halves, so that each plate had 48 microwells in it. Eggs (1–2 days old), one each, were counted into individual micro-wells of the plates using a binocular microscope (Olympus SZ 61). The microtiter plates were then kept inside individual desiccators 2.8 L (test chambers). The eggs were treated to different concentrations of phosphine ranging from 0.25 mgL−1 to 6.0 mgL−1 for 4 different exposure periods viz., 24, 48, 72 and 96 h with 4 replicates each along with equal number of controls. After the exposure period, the plate set up was held in a temperature/humidity controlled cabinet at 30 ± 2 °C and 70 ± 5 % R.H. Daily counts were made on the numbers hatched till there was no further hatching. Wherever, there was hatching, about 300 mg of whole wheat flour was added to the micro-well as food source for the emerging larvae. Mortality rates on reaching 14 days (end point mortality) were determined.

Toxicity studies on larval instars and pupae

Early 2nd instar (0–1 day old), mid 4th instar (8–9 days old) and late 6th instar (14–15 days old) and pupae (2–3 days old) were taken in 7 × 12 cm size glass tubes separately. There were 30 insects in a tube (replicate). In the tubes containing larvae and pupae about 2 g of culture medium was added to avoid starvation. The open-end of the tubes were covered with pieces of muslin cloth held by rubber rings. The tubes containing the insects were placed individually in desiccators (test chamber) of 2.8 L capacity for PH3 treatment. Four replicates were maintained for each life stage for each exposure period (total 7 exposure periods) with equal number of untreated controls. Each life stage was exposed to phosphine for 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144 and 168 h respectively. At the end of the exposure period, the life stages were removed from the test chambers and were transferred to tubes containing 5 g of culture medium and incubated at 30 ± 2 °C and 70 ± 5 % R.H. Mortality assessments were carried out for larval stages after 14 days of recovery period. The pupae were under regular observation, till adults started emerging. Adult emergence was then recorded on alternate days till no more adults emerged.

Statistical analysis

The corrected mortality data for the life stages were subjected to probit analysis (Polo Plus, Ver. 2.0 LeOra Software 2002) to determine LC50 and LC99 values together with fiducial limits and Chi-square tests were performed.

Results and discussion

The susceptibility of eggs, the larval instars and pupae increased with the length of exposure to phosphine as evident from the LC50 and LC99 values given in Table 1. The LC50 and LC99 values derived from the mortality assessment data after 14 days of recovery period showed that the extended exposures led to a linear decrease in the (LC50 and LC99) concentrations obtained irrespective of the developmental stages. However, the difference in the LC50 and LC99 concentrations obtained after the treatment period of 144–168 h did not show any remarkable change. The data also revealed that the effect of phosphine on the immature stages vary in their response to stepwise increase in concentration as well as exposure periods. At 24 h exposure, the maximum LC50 value was observed in case of egg; 1.571; followed by the pupae, 6th instar, 4th instar and 2nd instar larvae with LC50 values of 1.184, 0.336, 0.212 and 0.081 mgL−1 respectively. However, at 48, 72 and other subsequent treatment periods (96, 120, 144 and 168 h), the pupae proved to be tolerant among the developmental stages recording higher LC values. When the exposure periods where lengthened, considerable decrease in the LC50 and LC99 values were noticed in the dormant stages, the egg and the pupae. The possible reason for extending the exposure time is that the phosphine tolerant immature stages, the egg and pupa will develop to susceptible stages, i.e., larva and adult respectively during the course of fumigation and succumb (Winks and Ryan 1990). On the other hand, the susceptible larval instars showed a steady decrease in the LC50 and LC99 values. Similarly, it was reported that the LC50 values obtained after 24 h exposure to phosphine to be as 0.120 mgL−1 for the eggs, 0.003, 0.039, 0.090, 0.008 and 0.006 mgL−1 for 3, 4, 12, 19 and 25 days old larvae and 0.018 and 0.008 mg/L for the pupae and adults of T. castaneum respectively (Muthu 1974).

Table 1.

Toxicity of phosphine against immature stages of T. castaneum over different exposure periods at 25 ± 20 C and 70 ± 5 % R .H

| Insect Stage | LC50

(mg L−1) |

Fiducial limits | LC99

(mg L−1) |

Fiducial limits | Slope (b) ± SE | χ 2 (d.f) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | ||||||

| Egg | 1.571 | 1.255; 1.865 | 33.366 | 21.563; 63.968 | 1.753 ± 0.177 | 82.15 (36) |

| 2nd instar larvae | 0.081 | 0.076; 0.086 | 0.263 | 0.226; 0.322 | 4.556 ± 0.324 | 17.93 (23) |

| 4th instar larvae | 0.212 | 0.181; 0.243 | 2.025 | 1.575; 2.797 | 2.372 ± 0.169 | 23.49 (18) |

| 6th instar larvae | 0.336 | 0.296; 0.380 | 6.799 | 5.063; 9.732 | 1.781 ± 0.096 | 39.25 (38) |

| Pupae | 1.184 | 0.948; 1.497 | 66.963 | 35.576;159.256 | 1.323 ± 0.111 | 27.51 (19) |

| 48 h | ||||||

| Egg | 0.306 | 0.267; 0.344 | 2.140 | 1.757; 2.757 | 2.755 ± 0.197 | 9.63 (11) |

| 2nd instar larvae | 0.064 | 0.054; 0.073 | 0.238 | 0.190; 0.332 | 4.090 ± 0.441 | 31.37 (15) |

| 4th instar larvae | 0.124 | 0.111; 0.137 | 0.880 | 0.716; 1.131 | 2.730 ± 0.156 | 21.75 (20) |

| 6th instar larvae | 0.118 | 0.097; 0.140 | 2.332 | 1.555; 4.015 | 1.793 ± 0.138 | 57.23 (34) |

| Pupae | 0.509 | 0.239; 0.794 | 6.866 | 3.933; 20.023 | 2.059 ± 0.337 | 28.22 (9) |

| 72 h | ||||||

| Egg | 0.235 | 0.209; 0.258 | 0.763 | 0.644; 0.983 | 4.554 ± 0.496 | 10.80 (6) |

| 2nd instar larvae | 0.031 | 0.023; 0.037 | 0.092 | 0.064; 0.239 | 4.859 ± 1.078 | 64.09 (12) |

| 4th instar larvae | 0.073 | 0.066; 0.081 | 0.361 | 0.293; 0.473 | 3.371 ± 0.253 | 15.96 (14) |

| 6th instar larvae | 0.074 | 0.061; 0.086 | 0.693 | 0.498; 1.099 | 2.388 ± 0.209 | 39.54 (22) |

| Pupae | 0.203 | 0.166; 0.242 | 2.824 | 2.010; 4.457 | 2.033 ± 0.168 | 9.59 (13) |

| 96 h | ||||||

| Egg | 0.217 | 0.123; 0.281 | 1.051 | 0.706; 3.016 | 3.395 ± 0.695 | 27.01 (7) |

| 2nd instar larvae | 0.021 | 0.016; 0.026 | 0.151 | 0.095; 0.367 | 2.740 ± 0.428 | 35.15 (16) |

| 4th instar larvae | 0.051 | 0.043; 0.059 | 0.237 | 0.177; 0.380 | 3.506 ± 0.422 | 26.77 (15) |

| 6th instar larvae | 0.069 | 0.060; 0.078 | 0.612 | 0.459; 0.906 | 2.449 ± 0.207 | 26.81 (20) |

| Pupae | 0.108 | 0.089; 0.126 | 0.914 | 0.677; 1.402 | 2.507 ± 0.242 | 19.28 (12) |

| 120 h | ||||||

| 2nd instar larvae | 0.021 | 0.012; 0.029 | 0.174 | 0.091; 1.08 | 2.517 ± 0.600 | 119.46 (20) |

| 4th instar larvae | 0.037 | 0.263; 0.044 | 0.092 | 0.070; 0.198 | 5.848 ± 1.327 | 39.26 (9) |

| 6th instar larvae | 0.044 | 0.031; 0.056 | 0.425 | 0.263; 0.985 | 2.350 ± 0.336 | 66.78 (20) |

| Pupae | 0.070 | 0.047; 0.094 | 0.909 | 0.525; 2.476 | 2.094 ± 0.311 | 46.05 (15) |

| 144 h | ||||||

| 2nd instar larvae | 0.018 | 0.007; 0.024 | 0.063 | 0.041; 0.403 | 4.226 ± 1.252 | 56.50 (9) |

| 4th instar larvae | 0.034 | 0.027; 0.041 | 0.160 | 0.109; 0.336 | 3.446 ± 0.529 | 21.98 (10) |

| 6th instar larvae | 0.030 | 0.021; 0.038 | 0.219 | 0.147; 0.437 | 2.677 ± 0.366 | 20.67 (11) |

| Pupae | 0.049 | 0.027; 0.076 | 0.577 | 0.304; 2.100 | 2.189 ± 0.378 | 46.04 (10) |

| 168 h | ||||||

| 2nd instar larvae | 0.015 | 0.009; 0.019 | 0.064 | 0.043; 0.169 | 3.599 ± 0.741 | 58.51 (12) |

| 4th instar larvae | 0.024 | 0.021; 0.027 | 0.138 | 0.110; 0.190 | 3.062 ± 0.278 | 15.34 (17) |

| 6th instar larvae | 0.028 | 0.018; 0.042 | 0.991 | 0.415; 5.012 | 1.504 ± 0.230 | 63.62 (19) |

| Pupae | 0.040 | 0.032; 0.048 | 0.549 | 0.386; 0.885 | 2.043 ± 0.177 | 18.30 (11) |

The dose mortality response of eggs to phosphine over different exposure periods is given in Fig. 1. Significant increase in mortality of eggs was observed during initial treatment period of 24–72 h, the effectiveness increasing with doses that cause higher mortality. However, inhibition in egg hatch was observed in the egg which survived phosphine treatment at 24–72 h. At a treatment period of 96 h, 100 % mortality of eggs was observed at 2.5 mgL−1. Exposure of 1, 2 and 3 days old eggs of T. castaneum over 24 h, inhibited hatching at 58 and 115 ppm concentrations (Rajendran and Muthu 1991). To support this view, it has been reported that the susceptibility of insects to fumigants is known to vary considerably during their growth and to differences in the metabolic process of different stages (Bell and Glanville 1973).

Fig. 1.

Dose mortality response of eggs (1–2 days old) exposed to phosphine over different exposure periods

The significant increase in larval mortality, irrespective of the larval instars was apparent during the initial treatment period of 24–120 h, the extent of increase varying with dose and the exposure period as shown in Figs. 2, 3 and 4. Among the larval instars, the 2nd instar larvae (2–3 days old) proved susceptible to phosphine, which recorded 0.187 mgL−1 as the LC99 value at 24 h exposure, which dropped down to 0.042 mgL−1 when the exposure period was further extended to 168 h. In the case of mid larvae (8–9 days old), the obtained LC99 value was about 1.046 mgL−1 over 24 h exposure. Continued exposure of mid-larvae to 168 h brought down the LC99 value to 0.083 mgL−1.

Fig. 2.

Dose mortality response of 2nd instar larvae (2–3 days old) exposed to phosphine over different exposure periods

Fig. 3.

Dose mortality response of 4th instar larvae (8–9 days old) exposed to phosphine over different exposure periods

Fig. 4.

Dose mortality response of 6th instar larvae (14–15 days old) exposed to phosphine over different exposure periods

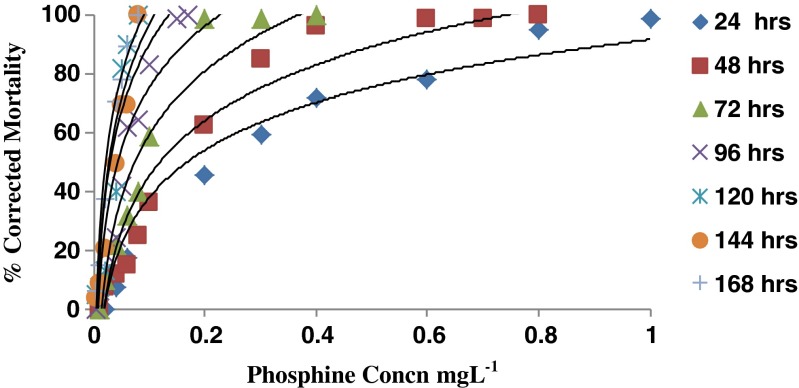

The dose mortality response of pupae over exposure to phosphine for different exposure periods is depicted in Fig. 5. The LC99 values for the pupae showed a gradual decrease in their levels from 20.33 mgL−1 at 24 h, to 0.28 mgL−1 at 144 h exposure. However, no significant difference in the LC99 values was observed between 144 and 168 h exposure to phosphine. It was also observed that the treatment of pupae to phosphine led to the development of deformed adults which could survive only a few days. The pupae of T. castaneum and T. confusum were tolerant than larvae or adults (Bang and Telford 1966). The effect of phosphine is more in long than in shorter periods, where the additional time in exposure will improve the chance that the tolerant stage will reach a susceptible stage and succumb while being fumigated (Bell 1979). In support to the view of the present study, it has been suggested that the exposure time with respect to phosphine fumigant is vital than its dosage in many cases (Annis and Banks 1993).

Fig. 5.

Dose mortality response of pupae (2–3 days old) exposed to phosphine over different exposure periods

Conclusion

To summarize, it is imperative that insects surviving repeated ineffective exposure, may give rise to resistant populations. While, the survival of phosphine tolerant immature stages may ascertain their ability to gain higher resistance compared to the susceptible stages surviving the treatments. Hence, increase in toxic effect of phosphine on T. castaneum may be achieved over increasing exposure periods irrespective of the insect stage. Though, considering larvae as the susceptible stage, wide variation in mortality response was observed among the larval instars. The results also suggest that, considerable difference in the mortality may be achieved during 24–120 h of initial treatment periods, especially in the phosphine susceptible, larvae and adults. Further, the extension of exposure period up to 144–168 h would increase the probability of phosphine tolerant egg and pupae to exterminate during their course of development. The implication of the above investigations indicate the need to extend the length of exposure period sufficiently in fumigations involving phosphine to preclude the chances of survival of immature stages especially the tolerant egg and the pupae during field applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Late Dr. N. Gunasekaran for his constant support and guidance for carrying out the experiments, Mrs. Megha for Technical Assistance and Dr. Rajendran and Dr. Bhanu Prakash for their comments/critics on the article and Director, CFTRI for his encouragement.

References

- AFHB/ACIAR . Suggested recommendations for the fumigation of grain in the ASEAN region. Part I. Principles and general practice. Kaula Lumpur: AFHB/ACIAR, Canberra; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Annis PC, Banks HJ. A predictive model for phosphine concentration in grain storage structures. In: Navarro S, Donahaye EJ, editors. Proceedings of international conference on controlled atmosphere and fumigation in grain storages, June 1992, Winnipeg. Jerusalem, Israel: Canada. Caspit Press; 1993. pp. 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Bang YH, Telford HS. Effect of sub lethal doses of fumigants on stored-grain insects. Tech Bull Wash St Univ Agricul Expl Stn. 1966;50:22. [Google Scholar]

- Bell CH. The efficiency of phosphine against diapausing larvae of Ephestia elutella (Lepidoptera) over a wide range of concentrations and exposure times. J Stored Prod Res. 1979;15:53–58. doi: 10.1016/0022-474X(79)90012-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell CH, Glanville V. The effect of concentration and exposure in tests with methyl bromide and with phosphine on diapausing larvae of Ephestia elutella (Hübner) (Lepidoptera, Pyralidae) J Stored Prod Res. 1973;9:65–170. doi: 10.1016/0022-474X(73)90012-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bengston M, Sidik M, Halid H, Alip E. Efficacy of phosphine fumigations on bagged milled rice under polyethylene sheeting in Indonesia. In: Donahaye EJ, Navarro S, Varnarva A, editors. Proceedings of the international conference on controlled atmospheres and fumigation in stored products, 21–26 april 1996, Nicosia, Cyprus. Nicosia, Cyprus: Printco Ltd.; 1997. pp. 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PJ, Daglish GJ, Benston M, Lambkin TM, Pavic H (2002) Genetics of resistance to phosphine in Rhyzopertha dominica (Coleoptera: Bostrichidae). J Econ Entomol 95(4):862–869 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Collins PJ, Daglish G, Pavic H, Koittke RA. Response of mixed-age cultures of phosphine-resistant and susceptible strains of lesser grain borer. Rhyzopertha dominica, to phosphine at a range of concentrations and exposure periods. J Stored Prod Res. 2005;41:373–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jspr.2004.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devi KC, Devi SS (2013) Insecticidal and oviposition deterrent properties of some spices against coleopteran beetle, Sitophilus oryzae. J Food Sci Technol 50(3):600–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization) Recommended methods for the detection and measurement of resistance of agricultural pests to pesticides. Tentative method for adults of some major beetle pests of stored cereals with methyl bromide and phosphine. FAO method No. 16. FAO Plant Prot Bull. 1975;23:12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Homayouni A, Azizi A, Keshtiban AK, Amini A, Eslami A (2014) Date canning: a new approach for the long time preservation of date. J Food Sci Technol. doi:10.1007/s13197-014-1291-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Howe RW. The susceptibility of immature and adult stages of Sitophilus granarius to phosphine. J Stored Prod Res. 1973;8:241–242. doi: 10.1016/0022-474X(73)90041-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaya SP, Prakash B, Dubey NK (2012) Insecticidal activity of Ageratum conyzoides L, Coleus aromaticus Benth. and Hyptis suaveolens (L.) Poit essential oils as fumigant against storage grain insect Tribolium castaneum Herbst. J Food Sci Technol 51(9):2210–2215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kedia A, Prakash B, Mishra PK, Singh P, Dubey NK (2013) Botanicals as eco friendly biorational alternatives of synthetic pesticides against Callosobruchus spp. (Coleoptera: Bruchidae)—a review. J Food Sci Technol 52(3):1239–1257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liang Y, Yan X, Qin Z, Wu X. An alternative to the FAO method for testing phosphine resistance of higher level resistance insects. In: Jin Z, Liang Q, Liang Y, Tan X, Guan L, editors. Stored product protection. Proceedings of the seventh international working conference on stored-product protection, 14–19 October 1998, Beijing, China. Chengdu, People’s Republic of China: Sichuan Publishing House of Science and Technology; 1999. pp. 607–611. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren DL, Vincent LE. Relative toxicity of hydrogen phosphide to various stored-product insects. J Stored Prod Res. 1966;2:141–146. doi: 10.1016/0022-474X(66)90018-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthu S. Some aspects of phosphine as a fumigant. In: Majumder SK, Venugopal JS, editors. Fumigation and gaseous pasteurization. Pest Cont. Sci: Mysore, Acad; 1974. pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Nakakita H. Stored rice and stored product insects. In: Nakakita H, editor. Rice inspection technology. Tokyo: ACE Corporation; 1998. pp. 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Nakakita H, Winks RG. Phosphine resistance in immature stages of a laboratory selected strain of Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) Coleoptera, Tenebrionidae) J Stored Prod Res. 1981;17:43–52. doi: 10.1016/0022-474X(81)90016-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey AK, Palni UT, Tripathi NN (2012) Repellent activity of some essential oils against two stored product beetles Callosobruchus chinensis L. and C. maculatus F. (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) with reference to Chenopodium ambrosioides L. oil for the safety of pigeon pea seeds. J Food Sci Technol 51(12):4066–4071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Price LA, Mills KA. The toxicity of phosphine to the immature stages of resistant and susceptible strains of some common stored product beetles, and their implications for their control. J Stored Prod Res. 1988;24:54–59. doi: 10.1016/0022-474X(88)90008-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajashekar Y, Gunasekaran N, Shivanandappa T (2010) Insecticidal activity of the root extract of Decalepis hamiltonii against stored-product insect pests and its application in grain protection. J Food Sci Technol 47(3):310–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rajashekar Y, Ravindra KV, Bakthavatsalam N (2012) Leaves of Lantana camara Linn. (Verbenaceae) as a potential insecticide for the management of three species of stored grain insect pests. J Food Sci Technol 51(11):3494–3499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rajendran S, Gunasekaran N. The response of phosphine-resistant lesser grain borer Rhyzopertha dominica and rice weevil Sitophilus oryzae in mixed-age cultures to varying concentrations of phosphine. Pest Manag Sci. 2002;58:277–281. doi: 10.1002/ps.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran S, Muralidharan N. Performance of phosphine fumigation of bagged paddy rice in indoor and outdoor stores. J Stored Prod Res. 2001;37:351–358. doi: 10.1016/S0022-474X(00)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran S, Muthu M. Effect of fumigants on the hatchability of eggs of Tribolium castaneum Herbst. Bull Grain Technol. 1991;29:117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran S, Narasimhan KS. The current status of phosphine fumigations in India. In: Highley E, Wright EJ, Banks HJ, Champ BR, editors. Proceedings of the 6th international working conference on stored-product protection. Canberra, Australia: CAB International; 1994. pp. 148–152. [Google Scholar]

- Sayaboc PD, Gibe AJG, Caliboso FM. Resistance of Rhyzopertha dominica (Coleoptera: Bostrichidae) to phosphine in the Philippines. Phil Entomol. 1998;12:91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RWD, Harris AH. The fumigation of bag-stacks with phosphine under gas-proof sheets using techniques to avoid the development of insect resistance. In: Highley E, Wright EJ, Banks HJ, Champ BR, editors. Stored products protection. Proceedings of the sixth international working conference on stored-product protection, 17–23 April 1994. Wallingford, UK: Canberra, Australia, CAB International; 1994. pp. 210–213. [Google Scholar]

- Winks RG. The effect of phosphine on resistant insects: In GASGA Seminar on fumigation technology for developing countries. London: Tropical Development Research Institute; 1986. pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Winks RG, Ryan R (1990) Recent developments in the fumigation of grain with phosphine. In: Fleurat-Lessard F, Ducom P (eds) Proceedings of the 5th International Working Conference on Stored-Product Protection, Bordeaux, France, pp 935–943