Abstract

Bran from different rice varieties is a treasure of nutrients and nutraceuticals, and its use is limited due to the poor sensory and functional properties. Application of enzymes can alter the functional and phytochemical properties. So the effect of endo-xylanase, cellulase and their combination on microstructural, nutraceutical and antioxidant properties of pigmented (Jyothi) and non-pigmented (IR64) rice bran were investigated. Scanning electron micrograph revealed micro structural changes in fibre structures on processing. All the enzymatic processing methods resulted in an increase in the content of oryzanol, soluble, bound and total polyphenols, flavonoid and tannin. It also showed an increase in the bioactivity with respect to free radical scavenging activity and total antioxidant activity. However, extent of the increase in bio-actives varied with the type of bran and enzyme application method. Endo-xylanase showed higher percentage difference compared to controls of Jyothi and IR64 bran extracts respectively in the content of the bound (10 & 19 %) and total (20 & 14 %) polyphenols. Combination of both the enzymes resulted in higher percentage increase of bioactive components and properties. It resulted in greater percentage difference compared to controls of Jyothi and IR64 extracts respectively in the content of soluble (58 & 17 %) and total (21 & 14 %) polyphenols, flavonoids (12 & 38 %), γ-oryzanol (10 & 12 %), free radical scavenging activity (64 & 30 %) and total antioxidant activity (82 & 136 %). It may be concluded that enzymatic bio-processing of bran with cellulose and hemicellulose degrading enzymes can improve its nutraceutical properties, and it may be used for development of functional foods.

Keywords: Rice bran, Cellulase, Endo-xylanase, γ-oryzanol, Polyphenols, Antioxidant activity

Introduction

Rice bran is a valuable by-product of rice milling, and it consists of aleurone and pericarp layers as well as germ. Its preventive or nutraceutical effects have been detected in hypercholesterolemia, hyperlipidemia, fatty liver, atherosclerosis, inflammatory disorders, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, etc. Rice bran obtained from different varieties of pigmented rice and non-pigmented rice have antioxidant compounds such as tocotrienol, tocopherol, oryzanol, sterols, polyphenols, etc., that help in preventing the damage of body tissue and oxidative damage to DNA caused by free radicals (Nagendra Prasad et al. 2011). Among these, gamma- oryzanol is not only a potent antioxidant (Xu et al. 2001) but also an effective cholesterol lowering (Raghuram et al. 1989) and anti-inflammatory agent (Akihisa et al. 2000). Min et al. (2012) reported that red and purple bran rices had significantly higher total phenolic and flavonoid concentrations and antioxidant capacities than light-coloured bran or other cereals,and they attribute it to their higher levels of proanthocyanidins and anthocyanins, respectively. Phenolic and flavonoid compounds in rice bran have antioxidative, antimutagenic, and anticancer potential (Nam et al. 2005) that play a significant role in maintaining health. Recent studies also showed that pigmented rice bran has bio-potent activities including the amelioration of iron deficiency, antioxidant, anti-carcinogenic, anti-atherosclerotic and anti-allergic properties (Deng et al. 2013). Rice bran nutraceutical properties can hence be exploited for the preparation of functional foods.

Although rice bran is an excellent source of nutraceuticals, except for few efforts (Jayadeep et al. 2009), its utility remains limited to the production of bran oil. Coarse fibrous texture and little sensory acceptability limit its use in food products for the preparation of functional foods (Sungsopha et al. 2009). Rice bran contains major polysaccharides like cellulose, hemicellulose and pentosans, which constitute the major part of the insoluble dietary fibre. Coarse nature of bran is due to lignin, polyphenolic fiber, in the matrix of hemicellulose and cellulose fibrils. The xylan is covalently linked to lignin and non-covalently to cellulose. These linkages contribute to the resistant nature of the bran layer (Hegde et al. 2006).

Bioprocessing plays a significant role in the improvement of health beneficial properties of foods. These foods contain a significant level of biologically active components that give health benefits beyond our basic needs (Revilla 2013; Jayadeep and Malleshi 2011). Enzymes cause minimal changes to original food compositions and therefore minimize the loss of important components (Parrado et al. 2006). Enzymatic processing can improve the functional, nutritional and sensory qualities of food ingredients and products. Enzymes, therefore, have found widespread applications in processing and production of all kinds of food products (Robert Whitehurst and Maarten, 2010). Major classes of enzymes are utilized in the processing of cereals. Such enzymes act mainly on the principal constituents of kernels: starch, protein and cell-wall polysaccharides (Poutanen 1997).

Carbohydrate degrading enzymes play a major role in food application as it has an added advantage of changing the physical, as well as nutraceutical properties of food ingredients. Das et al. (2008) reported that enzymatic processing of brown rice with cellulase and xylanase resulted in changes in physical property and increased ƴ-amino butyric acid (GABA) concentration. Alrahmany and Tsopmo (2012) reported that treatment of oat bran with enzymes like viscozyme, celluclast, alpha-amylase, and amyloglucosidase resulted in the increase in total phenolic and antioxidant activity of oat bran. Treatment of rice bran with other enzymes such as phytase and xylanase are reported to have resulted in high yield of rice bran protein isolate (Wang et al. 1999). Available information clearly shows that there are no studies on the application of cell wall degrading enzymes in rice bran on nutraceutical properties.

It is hypothesized that disruption of complex fibrous matrix of bran can result in greater release of phytochemicals trapped in it. However, commercial enzyme preparations cannot break the insoluble fibre matrix, and they act partially as exoenzymes and liberate sugars. Therefore in the present investigation efforts were made to understand the effects of cell wall degrading enzymes such as endo-xylanase and cellulase acting individually, and in combination, on the nutraceutical properties of pigmented rice bran (Jyothi) and non-pigmented rice bran (IR-64).

Materials and methods

Materials

Paddy of IR 64 (non-pigmented) and Jyothi (Pigmented) were obtained from Seed Corporation in Karnataka. Cellulase from Aspergillus niger (1.4 U/mg solid) from Sigma-Aldrich, USA and Xylanase D-762-p (400 U/g solid) from Biocatalyst, UK, having endo-xylanase activity were used for the enzymatic processing of rice bran. Ferulic acid, Methanol, HCl, Petroleum ether, Folin ciocalteau reagent, Sodium Carbonate, Sodium Nitrate, Aluminum Chloride, Sodium hydroxide and Phosphomolybdenum were procured from SISCO Research Lab, Mumbai, India. Alpha-tocopherol, Catechin, 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH+) and Vanillin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Bran preparation

Paddy was subjected to de-husking in a rubber roll sheller. Polishing operation was carried out in the laboratory using Satake grain testing machine having abrasion type polisher. Degree of polish of IR 64 was found to be 6.6 % while that of Jyothi was 7.6 %. Bran passed through 30 mesh size sieve was used for further analysis.

Enzymatic processing of rice bran

Enzymatic processing conditions of rice bran were optimized based on preliminary trials in the lab. Two grams each of rice bran samples were incubated separately with 20 mg each cellulase and xylanase in 2 ml distilled water, and mixture of 20 mg each of enzymes in 2 ml distilled water in a glass petri plate with lid at 50 °C for 90 min. Later the processed samples were dried at 50 °C in a drier by keeping the lid open. Bran without enzyme addition acted as the control. The dried bioprocesed bran samples were scraped off, pulverized in a pestle and mortar, and kept at −4 °C till analysis. Triplicate of the process was carried out.

Sample extraction for various analyses

Rice bran samples were extracted using different solvents for the quantification of various compounds. For oryzanol estimation, samples obtained by extracting the bran twice with known volume of petroleum ether (60–80) by incubating in water bath at 65 °C for about 7 min, collecting the supernatants and making up to a known volume with petroleum ether. Extract centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 7 min and the supernatant used for analysis. For soluble and bound polyphenols estimation, bran samples was extracted in methanol and 1 % HCl methanol respectively for 1 h at RT (28 °C) by mixing in tube mixer, centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 7 min and collection of supernatant by filtration through Whatman No.1. For flavonoid estimation, the bran samples were defatted at RT for 1 h with petroleum ether and kept overnight for drying. Subsequently the samples extracted with 1 % HCl methanol at RT for 1 h. and supernatant collected as explained above.

γ-oryzanol content

The oryzanol content was determined by the method described by Rogers et al. (1993); Seetharamaiah and Prabhakar (1986). The supernatant absorbance was recorded at 314 nm after appropriate dilution with petroleum ether, and the oryzanol content was calculated on the basis of the absorbance of 1 % standard oryzanol solution at 314 nm.

Polyphenols content

Total polyphenol content (soluble and bound) was measured by the method described by Singleton et al. (1999). Known volume of extract made up to 250 μl with distilled water, and the sample was mixed with 250 μl of Folin ciocalteau reagent and 500 μl of 20 % Na2CO3. The final volume was adjusted to 5 ml using distilled water. The reaction mixture was incubated in the dark for 30 min, and samples were then centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min. Absorbance of the supernatant measured at 760 nm in a spectrophotometer. A calibration curve was constructed with different concentrations of ferulic acid as standard. The results were expressed as mg of ferulic acid equivalent/100 g of sample.

Flavonoid content

Flavonoids were assayed as described by Jia et al. (1999) with slight modification. A known amount of above-mentioned extract was taken and made up to 500 μl with distilled water. To this mixture 75 μl of 5 % sodium nitrite was added, allowed to stand for 5 min, after which 150 μl of 10 % AlCl3 was added and incubated at room temperature for 6 min., after which 0.5 ml of 1 M NaOH was added, and sample mixture was incubated in dark for 15 min. It was then centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 5 min, and the absorbance was recorded at 512 nm. The flavonoid content was expressed as mg of catechin equivalent/100 g of sample.

Tannin content

A known amount of 1 % acidic methanol extract of rice bran was made up to 250 μl by adding 1 % acidic methanol. To the extract, freshly prepared vanillin-HCl reagent was added; sample blank was made without adding the extract. The samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature and O.D was read at 500 nm against sample blank, using catechin as standard (Robert 1971).

DPPH+ radical scavenging assay

The free radical scavenging activities of rice bran methanolic extracts were tested for their ability to scavenge the stable radical DPPH. The antioxidant activity using DPPH (2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) assay was assessed by the method of Bondet and Williams (1997). The reaction mixture contained 0.08 mg/ml DPPH in methanol and different concentration of rice bran extract. After 30 min. incubation at room temperature, the absorbance of the solution was measured at 517 nm and the scavenging activity were calculated as the percentage of radical reduction. Catechin was used as the reference compound.

Total antioxidant capacity assay

The total antioxidant capacity assay was determined as described by Prieto et al. (1999) with slight modification. Known concentration of methanolic extract was taken, and 1 ml of Phosphomolybdenum reagent added. The tubes were capped and incubated in a dry bath at 90 °C for 90 min. After cooling to room temperature, the absorbance of the reaction mixture was measured at 695 nm against a blank. α-tocopherol was used as standard and total antioxidant capacity expressed as equivalent of α –tocopherol.

Scanning electron microscopy analysis of rice bran

Rice bran samples were defatted using petroleum ether/methanol and dried at 50 °C in drier and kept in desiccators for SEM analysis. In addition to experimental samples bran not undergone any processing used as raw, and defatted as above. The bran particles were fixed on metal stub using double-sided cello tape and coated with gold (∼100 A°) in the KSE 24 M high vacuum evaporator. Then the topographical features of the samples were viewed under a scanning electron microscope (LEO 435VP, LEO Electron Microscopy Ltd., Cambridge, England), and the selected regions of the samples depicting distinct morphological features were photographed.

Statistical analysis

A statistical analysis was carried out using the student t-test to determine the level of significance of the values (Snedecor and Cochran, 1994). The values in the tables are expressed as mean ± SD (standard deviation) of three observations. The p value of less than 0.05 is taken as significant.

Results and discussion

Effect of enzymatic treatment on rice bran oryzanol content

The oryzanol content in rice bran was determined after enzymatic processing, and the results are presented in Table 1. Analysis of oryzanol content in IR-64 bran after treatment with cellulase, xylanase and with the combination of enzymes resulted in 3.6, 7.1 and 11.9 % higher oryzanol level respectively than the control value (263 mg/100 g). Content of oryzanol in the Jyothi bran was found to be lower compared to IR-64, and this may be due to the higher degree of polishing and varietal difference. Jyothi bran depicted about 3.0, 4.9 and 9.6 % higher yield of oryzanol with cellulase, xylanase and the combination of enzyme treatment respectively in comparison to control (159.2 mg/100 g). All values were observed to be statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Effect of enzyme treatment on oryzanol (mg/100 g) content of IR-64 and Jyothi rice bran

| Sample | IR-64 | Jyothi |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 267.3 ± 0.75a | 159.24 ± 1.13a |

| Cellulase | 276.8 ± 0.49b | 164.04 ± 0.49b |

| Xylanase | 286.3 ± 1.34b | 167.01 ± 0.95b |

| Cellulase + Xylanase | 299.2 ± 1.14b | 174.45 ± 1.31b |

Values with different alphabet significant at p < 0.05 compared to control

Enzyme mixtures with combined activity are known to provide better results than individual enzymes. The increase in oryzanol content, upon treatment using the combination of enzymes, may be because of changes in cell-wall structural components as reported in oil seed (Rosenthal and Niranjan, 1996).Sungsopha et al. (2009) reported that rice bran treated with enzymes such as protease and amylase resulted in about 22 % increase in oryzanol content compared to untreated rice bran. Results show that enzymatic processing especially in combination led to a higher increase compared to control in content of oryzanol in both the varieties of rice bran.

Effect of enzymatic treatment on rice bran polyphenol content

Rice bran treated with enzymes was assessed for the content of polyphenols, and the results are presented in Table 2. Analysis of soluble polyphenols in enzyme treated IR-64 rice bran resulted in 13 and 17 % increase respectively with cellulase and combination compared to control (278.4 mg Ferulic acid (FA) Equivalent/100 g). In the case of bound polyphenol content, xylanase treatment alone showed a significant increase of 19 % when compared to control (254.9 mg FA Equivalent/100 g). In the case of total polyphenols, 10, 14 and 40 % increase were observed with cellulase, xylanase and in combination, compared to control (533 mg Ferulic acid Equivalent/100 g). In Jyothi bran corresponding treatments resulted in 48, 49 and 58 % increase in soluble polyphenols compared to control(502 mg FA Eq/100 g); 6, 9 and 8 % increase in bound polyphenol compared to control(1451 mg FA Eq/100 g); and 17, 20 and 21 % increase in total polyphenols compared to control (1953 mg FA Eq/100 g). All the values were found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Effect of enzyme treatment on polyphenol content (mg FA/100 g) of IR-64 rice bran

| Sample | Soluble | Bound | Soluble | Bound |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR64 | Jyothi | |||

| Control | 278 ± 14a | 255 ± 17a | 502.5 ± 13a | 1451 ± 19a |

| Cellulase | 314 ± 6b | 272 ± 4a | 741.5 ± 11b | 1534 ± 16b |

| Xylanase | 304 ± 4a | 305 ± 4b | 752.5 ± 22b | 1588 ± 15b |

| Cellulase + Xylanase | 324 ± 3b | 285 ± 2a | 794.9 ± 05b | 1567 ± 15b |

Values with different alphabet in a column significant at p < 0.05 compared to control

In the case of polyphenols, difference in enzyme action in varieties may be due to the higher (2 time) difference in polyphenol content. Ferulic acid can exist in free, soluble, conjugated and bound form. Bound ferulic acid was significantly higher (> 93 % of total) than the soluble conjugated ferulic acid in corn, wheat, oats and rice (Adil et al. 2012). Tian et al., (2004) reported that, in rice grain, phenolic compounds were mainly in an insoluble form. Sungsopha et al. (2009) reported that enzymatic treatment of rice bran was able to improve the concentration of total Phenolic components (TPC). Alrahmany and Tsopmo (2012) also reported that treatment of oat bran with carbohydrase enzymes increase the total polyphenol content. These observations could be attributed to an increased degradation of the cell-wall structure as a result of the hydrolysis of cell-wall components, especially glycosidic bonds/linkages between phenolic compounds and cell-wall polysaccharides (Yadav et al. 2013).

Effect of enzymatic treatment on rice bran flavonoid content

Enzyme treated rice bran were analyzed for flavonoid content, and the results are depicted in Table 3. Treatment of IR-64 bran with cellulase, xylanase and in combination resulted in 26, 13 and 38 % increase in flavonoid content respectively compared to control (32 mg Catechin Equivalent (CAT Eq)/100 g). In Jyothi bran, it resulted in 4.9, 3 and 12 % increase respectively which are significant compared to control (113 mg CAT Eq/100 g). Higher percentage increase in flavonoid content compared to individual enzymes action or control may be due to the liberation of bound flavonoids by the action of cell wall degrading enzymes such as cellulase and xylanase in combination. Breakdown of cell-wall polymers by carbohydrases and the consequent increase in the concentration of flavonoids in the extracts have been reported by Shuo et al. (2011) also.

Table 3.

Effect of enzyme treatment on flavonoid content (mg Catechin Eq:/100 g) of IR-64 and Jyothi rice bran

| Sample | IR-64 | Jyothi |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 32.2 ± 0.61a | 113.7 ± 0.60a |

| Cellulase | 40.5 ± 0.50b | 119.3 ± 0.60b |

| Xylanase | 38.1 ± 0.61b | 116.8 ± 0.61b |

| Cellulase + xylanase | 44.4 ± 0.61b | 127.7 ± 0.61b |

Values with different alphabet in a column significant at p < 0.05 compared to respective control

Effect of enzymatic treatment on rice bran tannin content

The results of tannin content of rice bran are presented in Table 4. In the present study, compared to control (4 mg CAT Eq/g), treatment of IR-64 rice bran resulted in 83 % increase with both cellulase and xylanase and 2 fold increase in enzymes acting in combination. However, tannin content in IR 64 is too small. On the other hand enzymatic treatment on Jyothi bran resulted in only 9, 14 and 7 % increase in tannin content upon treatment with cellulase, xylanase and enzyme combination respectively, compared to control (101 mg CAT Eq/g).

Table 4.

Effect of enzyme treatment on tannin content (mg Catechin Eq:/g) of IR-64 and Jyothi rice bran

| Sample | IR-64 | Jyothi |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 4 ± 1a | 101.3 ± 1.15a |

| Cellulase | 7 ± 1b | 110.2 ± 2b |

| Xylanase | 7.3 ± 0.6b | 115.33 ± 2.08b |

| Cellulase + Xylanase | 8.7 ± 0.6b | 108 ± 2.65b |

Values with different alphabet in a column significant at p < 0.05 compared to respective control

Compared to IR 64 the content of tannin is high in Jyothi rice. Pigmented rice is high in tannins, which are concentrated in the bran (Kaur et al. 2011). Enzymatic treatment is known to have a mild effect on the tannin content of rice bran that is having high tannin content. Ducassea et al. (2010)reported similar results in a study conducted on grape cell wall tannins. They established that the increase in tannins may be due to easier extraction of higher molecular weight tannins as a result of the increased degradation of grape cell walls induced by enzyme addition.

Effect of enzymatic treatment on free radical scavenging activity of rice bran

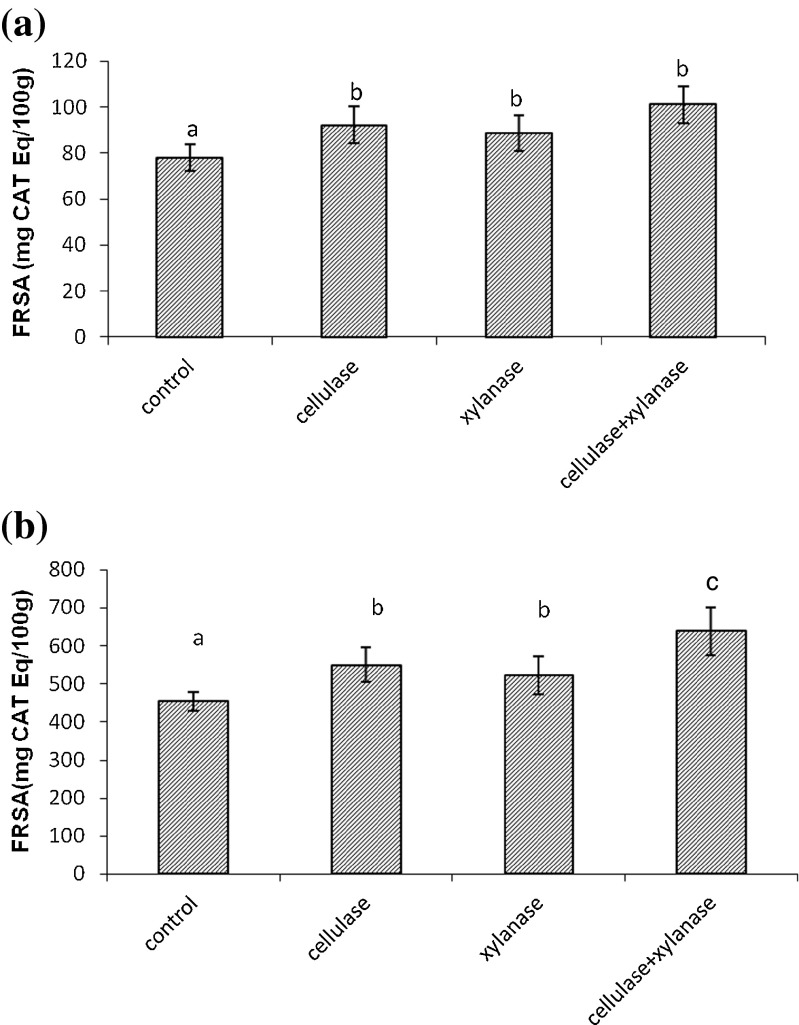

The treatment of IR64 bran with cellulase, xylanase and combination resulted in 18, 13 and 29 % (Fig. 1) increase in radical scavenging activity respectively, and in Jyothi bran it resulted in 21, 15 and 41 % increase in free radical scavenging activity compared to control (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Free radical scavenging activities(FRSA) by DPPH+ of control and carbohydrases treated samples. a Enzyme treated IR-64 variety b Enzyme treated Jyothi variety values are means of triplicates ± SD. Bars with different letters are significantly different at P < 0.05

When enzyme treated rice bran extract was subjected to radical scavenging activity analysis, it was found that the combination of cellulase and xylanase led to increased radical scavenging activity when compared to individual enzymes action or control. Sungsopha et al. (2009) reported that when rice bran was treated with amylase and protease, increase in the radical scavenging activity was noted and it is due to increase in bioactive components like polyphenol, flavonoid, etc., which are known to rise upon action with enzymes. The enzyme-treated rice bran extract demonstrates electron-donating capacity and thus they may act as radical chain terminators, which transformed the reactive free radical species into more stable non-reactive products (Arabshahi-Delouee and Urooj, 2007).

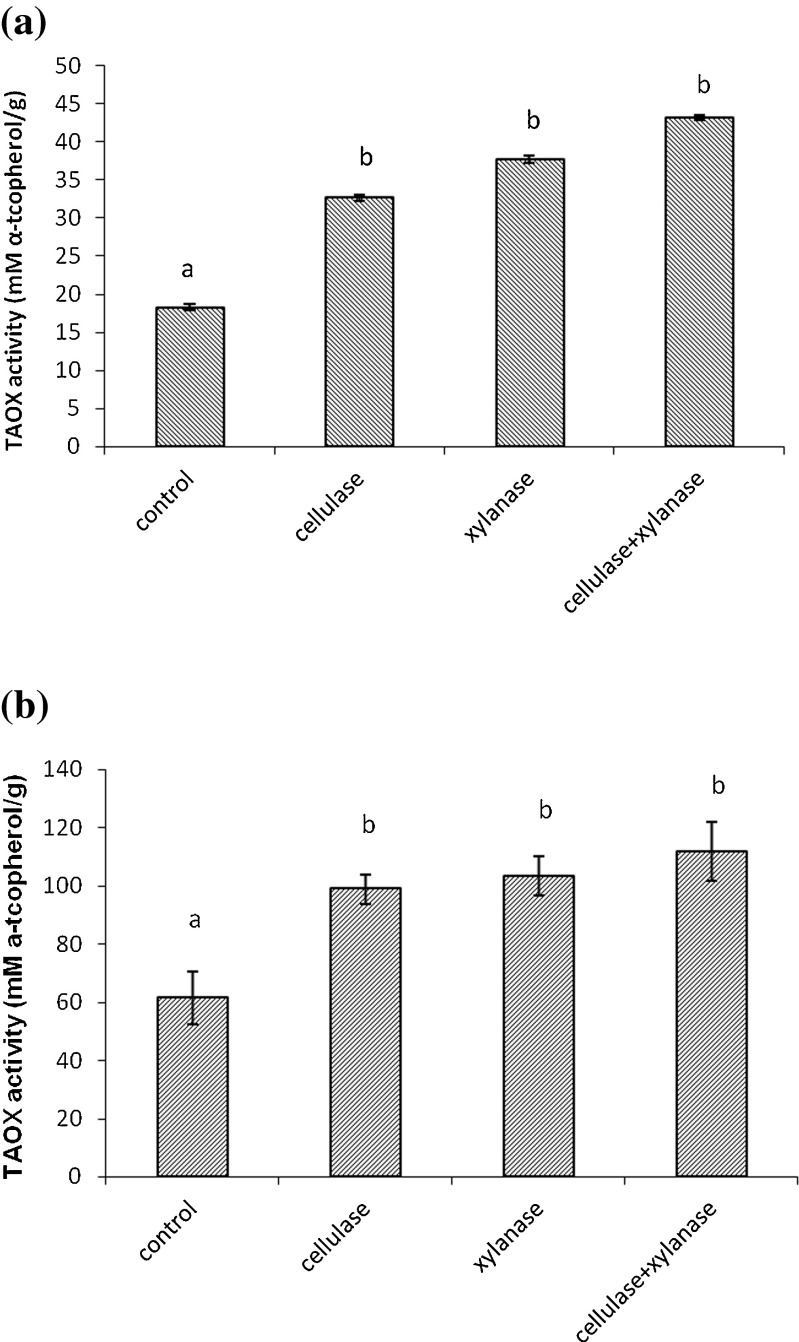

Effect of enzymatic treatment on total antioxidant activity of rice bran

In the present study, treatment of IR 64 rice bran with carbohydrases resulted in an increase of total antioxidant activity of 78 % upon treatment with cellulase, 106 % with xylanase and 136 % with combination of enzymes (Fig. 2). In Jyothi bran, enzyme treatment resulted in 60, 68 and 82 % increase in total antioxidant activity when treated with cellulase, xylanase and with combination of enzymes respectively, compared to control (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Total antioxidant activity(TAOX) of control and carbohydrases treated samples. a Enzyme treated IR-64 variety b Enzyme treated Jyothi variety Values are means of triplicates ± SD. Bars with different letters are significantly different at P < 0.05

Sungsopha et al. (2009)reported that treatment of rice bran with amylase and protease enzymes resulted in an increase in total antioxidant activity. The rice bran treated with xylanase and with combination of enzymes led to higher antioxidant activity because it liberates larger amount of oil soluble bioactive components like oryzanol and vitamin E. Vierhuis et al. (2001)reported cell-wall-degrading-enzymes such as cellulase and xylanase processing of rice bran can improve the phenolic concentration in the oil and thereby enhances antioxidant property.

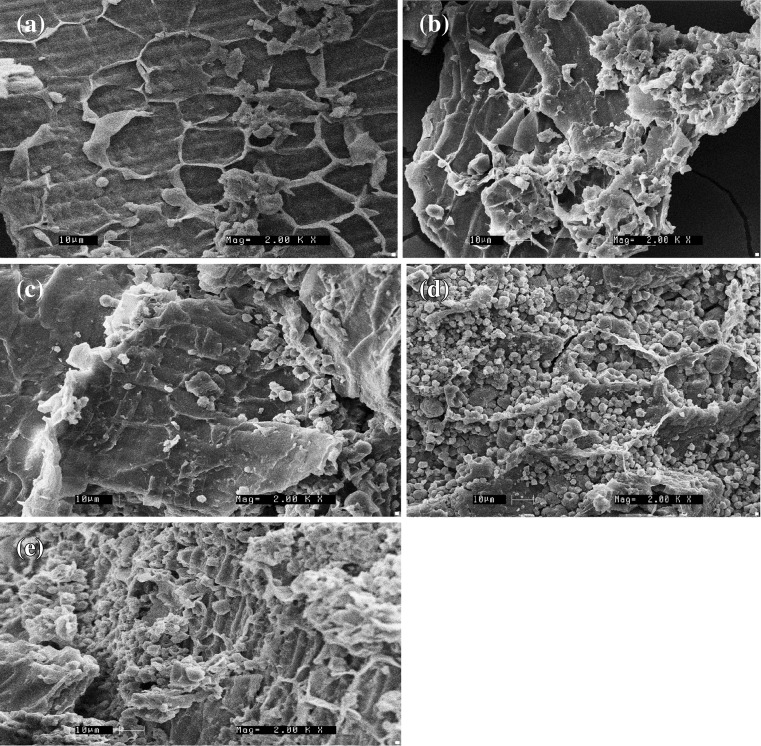

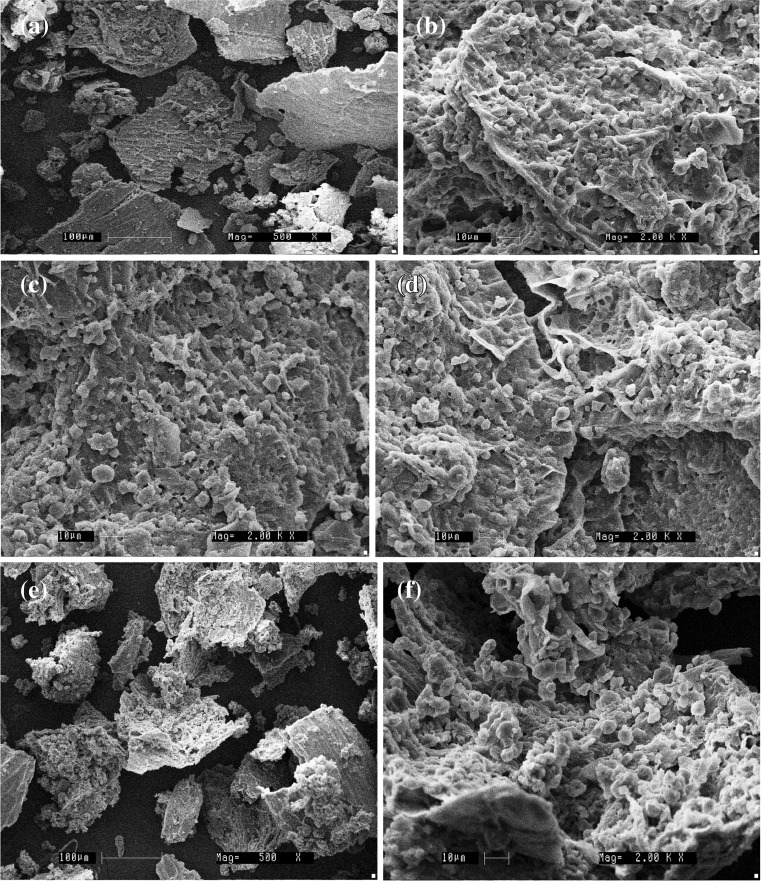

Microstructural changes by scanning electron microscopy

SEM was also conducted to understand better and to compare the microstructural changes on treatment with Xylanase, Cellulase and combination of enzymes on rice bran. In raw and control, honeycomb like cell wall structures with wings, were observed. On cellulase treatment, honeycomb structure looks to be disappearing especially due to the digestion of wings. But on xylanase treatment presence of the particle like structures similar to protein could be visible within the comb structure. Combination of enzymes resulted in higher degradation of bran structure compared to treatment with individual enzymes. The results of SEM of raw, control, xylanase, cellulase and combination of enzymes on IR-64 bran is shown in Fig. 3 and action of enzymes on Jyothi bran is shown Fig. 4. Dimitra and Constantina (2012) also reported changes in physical properties of rice bran and oat bran on treatment with endo-xylanase.

Fig. 3.

Effect of enzymatic processing on microstructure of IR64 rice bran. a Raw (2000X); b control (2000X); c cellulase treated (2000X); d xylanase treated (2000X); e combination treated (2000X)

Fig. 4.

Effect of enzymatic processing on microstructure of Jyothi rice bran. a Raw (500X); b Control (2000X); c Cellulase treated (2000X); d Xylanase treated (2000X); e Combination treated (500X); f Combination treated (2000X)

Overall effect of enzymatic processes in rice bran

Overall observation of the present study is that between endo-xylanase and cellulase, endo-xylanase resulted in higher percentage increase in bound polyphenols, total polyphenols, γ-oryzanol and total antioxidant activity, and cellulase resulted in greater percentage increase in flavonoid and free radical scavenging activity. Better efficiency of endo-xylanase may be due to its potential to disturb the hemicellulose lignin complex and consequent higher extractability of bioactive components. On the other hand, combination of enzymes is resulting in severe microstructural changes and greater increase in extractable bioactive components and bioactivity. This may be due to positive effect of endo-xylanse to disrupt the tough cell wall structure which is enabling cellulase to digest cellulosic material partially in the bran. Shuo et al. (2011) also reported that carbohydrases can increase the permeability and porosity of plant cells and improve the solubility of cell internal components. Effect of enzymatic process on different bran varieties showed that compared to respective controls, increase in soluble polyphenols, total polyphenols and free radical scavenging activity were more in Jyothi, whereas bound polyphenols, flavonoids, g-oryzanol and total antioxidant activity were more in IR64. Lower enzyme effect in Jyothi compared to IR64 on extractability of complex bio-molecules may be due to the inhibitory potential of higher content of polyphenols present in it (Ximenes et al. 2010).

Conclusions

Rice bran, in spite of its high health beneficial properties, is used as fodder for animals, due to its tough texture, less palatability and low storage properties. Enzymatic method is a new tool in food technology where in changes could be made in the physical and biofunctional properties for making it more feasible for edible purpose. In the present work,the effect of cell wall degrading enzymes such as cellulase and endo-xylanase individually as well as in combination in non-pigmented (IR-64) and pigmented (Jyothi) rice bran under optimized condition on nutraceutical properties were investigated. SEM observations revealed the micro-structural changes due to the action of enzyme activity. All the enzymatic processing also resulted in enhancement of nutraceuticals like oryzanol, polyphenols, flavonoid content and biopotency in terms of free radical scavenging activity and total antioxidant activity. Among the enzymatic processing, more than the individual enzymes, combination of enzymes is showing higher potency. Differences were also there in the effect of the enzymatic process in rice bran varieties on bioactive components in the extract. Enzymatic treatment of rice bran can be adopted as a method for improving the physical and nutraceutical properties for making functional food ingredient.

Acknowledgments

The authors like to thank The Director, CSIR-CFTRI, Mysore, for encouragement and support.

Footnotes

Highlights

• Rice bran is rich in nutraceuticals and its use is limited due to poor functional properties

• Since the application of enzymes can alter the properties, its effect on nutraceuticals studied

• Cellulase and endo-xylanase alone and in combination increased oryzanol and polyphenols

• Free radical scavenging activity and antioxidant activity increased on enzyme treatments

• Bioprocessing of non and pigmented bran can lead to functional food ingredient development

References

- Adil G, Wani SM, Masoodi FA, Gousia HG. Whole grain cereal bioactive bompounds and their health benefits: A Review. J Food Proc Technol. 2012;3:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Akihisa T, Yasukawa K, Yamaura M, Ukiya M, Kimura Y, Shimizu N, Arai K. Triterpene alcohol and sterol ferulates from rice bran and their anti-inflammatory effects. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:2313–2319. doi: 10.1021/jf000135o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alrahmany R, Tsopmo A. Role of carbohydrases on the release of reducing sugar, total phenolics and on antioxidant properties of oat bran. Food Chem. 2012;132:413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabshahi-Delouee S, Urooj AY. Antioxidant properties of various solvent extracts of mulberry (Morus indica) leaves. Food Chem. 2007;102:1233–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bondet V, Williams B, Berset (1997) Kinetics and mechanisms of antioxidant activity using the DPPH free radical method. LWT - Food Sci Technol 30: 609 – 615.

- Das M, Gupta S, Kapoor V, Banerjee R, Bal S. Enzymatic polishing of rice: A new processing technology. LWT - Food Sci Technol. 2008;41:2079–2084. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2008.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deng GF, Xu XR, Zhang Y, Li D, Gan RY, Li HB. Phenolic compounds and bioactivities of pigmented rice. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2013;53:296–306. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2010.529624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitra L, Constantina T. Use of endoxylanase treated cereal brans for development of dietaryfiber enriched cakes. Inn Food Sci Emerg Te chnol. 2012;13:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2011.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ducassea M, Marie R, Llauberes C, Lumley M, Williams P, Souquet J, Fulcrand H, Doco T, Cheynier V. Effect of macerating enzyme treatment on the polyphenol and polysaccharide composition of red wines. Food Chem. 2010;118:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.04.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde S, Kavitha S, Varadaraj MC, Muralikrishna G. Degradation of cereal bran polysaccharide-phenolic acid complexes by Aspergillus niger CFR 1105. Food Chem. 2006;96:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.01.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jayadeep A, Malleshi NG. Nutrients, composition of tocotrienols, tocopherols and gamma oryzanol and antioxidant activity in brown rice before and after germination. CyTA J Food. 2011;9:82–87. doi: 10.1080/19476331003686866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jayadeep A, Singh V, Rao BVS, Srinivas A, Ali SZ. Effect of physical processing of commercial de-oiled rice bran on particle size distribution and content of chemical and bio-functional Components. Food and Bioprocess Technol. 2009;2:57–67. doi: 10.1007/s11947-008-0094-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia ZS, Tang MC, Wu JM. The determination of Flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999;64:555–559. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(98)00102-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Sharma S, Nagi HPS. Functional properties and anti-nutritional factors in cereal bran. J Food Agric Ind Org. 2011;4:122–131. [Google Scholar]

- Min B, Gu L, McClung A M, Bergman C J, Chen M. Free and bound total phenolic concentrations, antioxidant capacities, and profiles of proanthocyanidins and anthocyanins in whole grain rice(Oryza sativa L.) of different bran colours. Food Chem. 2012;133:715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.01.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagendra Prasad MN, Sanjay KR, Shravya Khatokar M, Vismaya MN, Swamy N (2011). Health Benefits of Rice Bran - A Review. J Nutr Food Sci 1: 1–7.

- Nam SH, Choi SP, Kang MY, Kozukue N, Friedman M. Antioxidative, antimutagenic, and anticarcinogenic activities of rice bran extracts in chemical and cell assays. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:816–822. doi: 10.1021/jf0490293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrado J, Miramontes E, Jover M, Gutierrez JF, CollantesdeTeránand L, Bautista J. Preparation of a rice bran enzymatic extract with potential use as functional food. Food Chem. 2006;98:742–748. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poutanen K. Enzymes: and important tool for improving the quality of cereal foods. Trends Food Sci.Technol. 1997;8:300–306. doi: 10.1016/S0924-2244(97)01063-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto P, Pineda M, Aguilar M. Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of phosphomolybdenum complex: specific application to determination of vitamin E. Anal Biochem. 1999;269:337–341. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghuram T C, Rao MB, Rukmini C. Studies on hypolipidemic effects of dietary rice bran oil in human subjects. Nutr Rep Int. 1989;39:889–895. [Google Scholar]

- Revilla E, Santa–Maria C, Miramontes E, Candiracci M, Rodriguez-Morgado B, Carballo M, Bautista J, Castano A, Parrado J. Antiproliferative and immunoactivatory ability of an enzymatic extract from rice bran. Food Chem. 2013;136:526–531. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert EB. Method for estimation of tannin in grain sorghum. J. Agro Crop Sci. 1971;63:511. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Whitehurst J, Maarten VO. Enzymes in Food Technology. second. London, UK: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EJ, Rice SM, Nicolosl RJ, Carpenter DR, McClelland CA, Romanczyk LJ. Identification and quantification of γ-oryzanol components and simultaneous assessment of tocols in rice bran oil. J. Am. Oil Chem Soc. 1993;70:301–307. doi: 10.1007/BF02545312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal Pyle DL, Niranjan K. Aqueous and enzymatic processes edible oil extraction. Enzym Microb Technol. 1996;19:402–420. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(96)80004-F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seetharamaiah GS, Prabhakar JV. Oryzanol content of Indian rice bran oil and its extraction from soap stock. J.Food Sci.Technol. 1986;23:270–273. [Google Scholar]

- Shuo C, Xin-Hui X, Jian-Jun H, Ming-Shu X. Enzyme-assisted extraction of flavonoids from Ginkgo biloba leaves: improvement effect of flavonol transglycosylation catalyzed by Penicillium decumbens cellulase. Enzym Microb Technol. 2011;48:100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton VL, Orthofer R, Lamuela-Raventos RM. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Oxid Antioxid. 1999;299:152–178. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99017-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical methods. Eighth. Press, Iowa: Iowa State Univ; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sungsopha J, Moongngarm A, Kanesakoo R. Application of germination and enzymatic treatment to improve the concentration of bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of rice bran. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2009;3:3653–3662. [Google Scholar]

- Tian S, Nakamura K, Kayahara H. Analysis of phenolic compounds in white rice, brown rice, and germinated brown rice. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:4808–4813. doi: 10.1021/jf049446f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierhuis E, Servili M, Baldioli M, Schols HA, Alphons Voragen GJ, Montedoro GF. Effect of Enzyme Treatment during Mechanical Extraction of Olive Oil on Phenolic Compounds and Polysaccharides. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:1218–1223. doi: 10.1021/jf000578s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Hettiarachchy NS, Qi M, Burks W, Siebenmorgen T. Preparation and functional properties of rice bran protein isolate. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:411–416. doi: 10.1021/jf9806964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ximenes E, Kim Y, Mosier N, Dien B, Ladisch M. Inhibition of cellulases by phenols. Enzym Microb Technol. 2010;46:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Hua N, Godber JS. Antioxidant activity of tocopherols, tocotrienols, and g-Oryzanol components from rice bran against cholesterol oxidation accelerated by 2,2¢- azobis (2-methlypropionamidine) dihydrochloride. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:2077–2081. doi: 10.1021/jf0012852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav G, Singh A, Bhattacharya P, Yuvraj J, Banerjee R. Comparative analysis of solid-state bioprocessing and enzymatic treatment of finger millet for mobilization of bound phenolics Bioproc. Biosyst Eng. 2013;36:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00449-012-0755-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]