Abstract

Intellectual disability (ID) affects approximately 1%–3% of humans with a gender bias toward males. Previous studies have identified mutations in more than 100 genes on the X chromosome in males with ID, but there is less evidence for de novo mutations on the X chromosome causing ID in females. In this study we present 35 unique deleterious de novo mutations in DDX3X identified by whole exome sequencing in 38 females with ID and various other features including hypotonia, movement disorders, behavior problems, corpus callosum hypoplasia, and epilepsy. Based on our findings, mutations in DDX3X are one of the more common causes of ID, accounting for 1%–3% of unexplained ID in females. Although no de novo DDX3X mutations were identified in males, we present three families with segregating missense mutations in DDX3X, suggestive of an X-linked recessive inheritance pattern. In these families, all males with the DDX3X variant had ID, whereas carrier females were unaffected. To explore the pathogenic mechanisms accounting for the differences in disease transmission and phenotype between affected females and affected males with DDX3X missense variants, we used canonical Wnt defects in zebrafish as a surrogate measure of DDX3X function in vivo. We demonstrate a consistent loss-of-function effect of all tested de novo mutations on the Wnt pathway, and we further show a differential effect by gender. The differential activity possibly reflects a dose-dependent effect of DDX3X expression in the context of functional mosaic females versus one-copy males, which reflects the complex biological nature of DDX3X mutations.

Main Text

Intellectual disability (ID) affects approximately 1%–3% of humans with a gender bias toward males.1–4 It is characterized by serious limitations in intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior, starting before the age of 18 years.5 Though mutations causing monogenic recessive X-linked intellectual disability (XLID) have been reported in more than 100 genes,6,7 the identification of conditions caused by de novo mutations on the X chromosome affecting females only is limited.8,9

By undertaking a systematic analysis of whole exome sequencing (WES) data on 820 individuals (461 males, 359 females) with unexplained ID or developmental delay (from the Department of Human Genetics Nijmegen, the Netherlands), we identified de novo variants in DDX3X (MIM: 300160; GenBank: NM_001356.4) in seven females (1.9% of females). Exome sequencing and data analysis were performed essentially as previously described,10 and sequencing was performed in the probands and their unaffected parents (trio approach).11 To replicate these findings, we examined a second cohort of 957 individuals (543 males, 414 females) with intellectual disability or developmental delay from GeneDx (sequencing methods as previously published12) and a third cohort of 4,295 individuals with developmental disorders (2,409 males, 1,886 females) from the Deciphering Developmental Disorders (DDD) study (UK).13 In most individuals in these cohorts, a SNP array or array CGH had been performed as well and, based on the clinical findings, in several individuals additional metabolic testing, Fragile X testing, or targeted Sanger analysis of different genes associated with ID was completed previously. None of these prior analyses revealed the genetic cause in these individuals. We therefore refer to the individuals in these cohorts as individuals with unexplained ID. We identified 12 de novo alleles in DDX3X in the second cohort (2.9% of females) and 20 de novo alleles in the DDD cohort (1.1% of females). Consequently, based on our findings, mutations in DDX3X are one of the more common causes of ID, accounting for 1%–3% of unexplained ID in females. Altogether, 39 females with de novo variants in DDX3X were identified in our three cohorts and no de novo variants in DDX3X were identified in males (Fisher’s exact test: p = 4.815 × 10−9).

To further define this neurodevelopmental disorder, additional females with de novo DDX3X variants were collected from other clinical and diagnostic centers in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Italy, and Canada. In total, we obtained the complete clinical and molecular details of 38 females from across cohorts, which we present in this study. All legal representatives provided informed consent for the use of the data and photographs, and the procedures followed are in accordance with relevant institutional and national guidelines and regulations. The 38 females had 35 distinct de novo variants in DDX3X (Table 1). 19 of the 35 different alleles are predicted to be loss-of-function alleles (9 frameshift mutations leading to premature stop codon, 6 nonsense mutations, and 4 splice site mutations that possibly cause exon skipping), suggesting haploinsufficiency as the most likely pathological mechanism. The other variants, 15 missense variants and 1 in-frame deletion, are all located in the helicase ATP-binding domain or helicase C-terminal domain (Figure 1). One recurrent missense mutation was present in three females (c.1126C>T [p.Arg376Cys]), and in two females the same frameshift mutation, c.1535_1536del (p.His512Argfs∗5), was identified.

Table 1.

Mutation Characteristics

| Nucleotide Change (GenBank:NM_001356.4) | Amino Acid Change | SIFT | PolyPhen-2 | Cohort | Previously Reported | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | ||||||

| Individual 1 | c.1126C>T | p.Arg376Cys | not tolerated | probably damaging | Nijmegen | – |

| Individual 2 | c.233C>G | p.Ser78∗ | NA | NA | Nijmegen | – |

| Individual 3 | c.1126C>T | p.Arg376Cys | not tolerated | probably damaging | DDD Study | DDD Study13 |

| Individual 4 | c.136C>T | p.Arg46∗ | NA | NA | DDD Study | DDD Study13 |

| Individual 5 | c.1601G>A | p.Arg534His | not tolerated | probably damaging | DDD Study | DDD Study13 |

| Individual 6 | c.641T>C | p.Ile214Thr | not tolerated | probably damaging | DDD Study | DDD Study13 |

| Individual 7 | c.1520T>C | p.Ile507Thr | not tolerated | probably damaging | other | – |

| Individual 8 | c.977G>A | p.Arg326His | not tolerated | probably damaging | other | – |

| Individual 9 | c.868del | p.Ser290Hisfs∗31 | NA | NA | other | Rauch et al.41 |

| Individual 10 | c.1229_1230dup | p.Thr411Leufs∗10 | NA | NA | Nijmegen | – |

| Individual 11 | c.1105dup | p.Thr369Asnfs∗14 | NA | NA | Nijmegen | – |

| Individual 12 | c.865−2A>G | p.? | NA | NA | Nijmegen | – |

| Individual 13 | c.1600dup | p.Arg534Profs∗13 | NA | NA | other | – |

| Individual 14 | c.269dup | p.Ser90Argfs∗8 | NA | NA | Nijmegen | – |

| Individual 15 | c.1440A>T | p.Arg480Ser | not tolerated | probably damaging | Nijmegen | – |

| Individual 16 | c.873C>A | p.Tyr291∗ | NA | NA | Nijmegen | – |

| Individual 17 | c.1693C>T | p.Gln565∗ | NA | NA | Nijmegen | – |

| Individual 18 | c.1535_1536del | p.His512Argfs∗5 | NA | NA | DDD Study | – |

| Individual 19 | c.766−1G>C | p.? | NA | NA | other | – |

| Individual 20 | c.599dup | p.Tyr200∗ | NA | NA | USA | – |

| Individual 21 | c.1321del | p.Asp441Ilefs∗3 | NA | NA | USA | – |

| Individual 22 | c.1383dup | p.Tyr462Ilefs∗3 | NA | NA | USA | – |

| Individual 23 | c.1384_1385dup | p.His463Thrfs∗34 | NA | NA | USA | – |

| Individual 24 | c.1535_1536del | p.His512Argfs∗5 | NA | NA | USA | – |

| Individual 25 | c.1541T>C | p.Ile514Thr | not tolerated | probably damaging | USA | – |

| Individual 26 | c.704T>C | p.Leu235Pro | not tolerated | probably damaging | USA | – |

| Individual 27 | c.1175T>C | p.Leu392Pro | not tolerated | probably damaging | USA | – |

| Individual 28 | c.1463G>A | p.Arg488His | not tolerated | possibly damaging | USA | – |

| Individual 29 | c.1126C>T | p.Arg376Cys | not tolerated | probably damaging | USA | – |

| Individual 30 | c.1250A>C | p.Gln417Pro | not tolerated | probably damaging | USA | – |

| Individual 31 | c.698C>T | p.Ala233Val | not tolerated | probably damaging | DDD Study | – |

| Individual 32 | c.931C>T | p.Arg311∗ | NA | NA | DDD Study | – |

| Individual 33 | c.46-2A>C | p.? | NA | NA | DDD Study | – |

| Individual 34 | c.1678_1680del | p.Leu560del | NA | NA | DDD Study | – |

| Individual 35 | c.1423C>G | p.Arg475Gly | not tolerated | probably damaging | DDD Study | – |

| Individual 36 | c.46-2A>G | p.? | NA | NA | DDD Study | – |

| Individual 37 | c.1703C>T | p.Pro568Leu | not tolerated | probably damaging | DDD Study | – |

| Individual 38 | c.1526A>T | p.Asn509Ile | not tolerated | probably damaging | DDD Study | – |

| Males | ||||||

| Family 1 | c.1084C>T | p.Arg362Cys | not tolerated | probably damaging | – | – |

| Family 2 | c.1052G>A | p.Arg351Gln | not tolerated | possibly damaging | – | Hu et al.7 |

| Family 3 | c.898G>T | p.Val300Phe | not tolerated | probably damaging | – | – |

“Other” indicates additional females with de novo DDX3X mutations collected from different diagnostic centers in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Italy, and Canada.

Figure 1.

Location of Amino Acid Substitutions in DDX3X

Schematic view of DDX3X with the 15 different amino acid substitutions (and one in-frame deletion) found in affected females and the 3 different amino acid substitutions found in affected males. DDX3X consists of two subdomains: a helicase ATP-binding domain and a helicase C-terminal domain. All amino acid substitutions found in affected females are located within these two protein domains. The three amino acid substitutions found in affected males are all located within the helicase ATP-binding domain.

Analysis of the clinical data suggested a syndromic disorder with variable clinical presentation. The females (age range 1–33 years) showed varying degrees of ID (mild to severe) or developmental delay with associated neurological abnormalities, including hypotonia (29/38, 76%), movement disorders comprising dyskinesia, spasticity, and a stiff-legged or wide-based gait (17/38, 45%), microcephaly (12/38, 32%), behavior problems including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), hyperactivity, and aggression (20/38, 53%), and epilepsy (6/38, 16%). Several recurrent additional features were noted, including joint hyperlaxity, skin abnormalities (mosaic-like pigmentary changes in some females), cleft lip and/or palate, hearing and visual impairment, and precocious puberty. Abnormal brain MRIs were reported in various females, with corpus callosum hypoplasia (13/37, 35%), ventricular enlargement (13/37, 35%), and evidence of cortical dysplasia (e.g., polymicrogyria) in four individuals. A summary of the clinical data is presented in Tables 2 and S1, and facial profiles of 30 of the 38 females are shown in Figure 2. Although common dysmorphic features are reported, there is no consistent recognizable phenotype. Based on these clinical and molecular data, there is no evidence for an obvious genotype-phenotype correlation between the different types of mutations and degree of ID.

Table 2.

Clinical Features of Females with De Novo DDX3X Mutations

| Percentage | Number | |

|---|---|---|

| Development | ||

| Intellectual disability or developmental delay | 100% | 38/38 |

| Mild or mild-moderate disability | 26% | 10/38 |

| Moderate or moderate-severe disability | 26% | 10/38 |

| Severe disability | 40% | 15/38 |

| Developmental delay | 8% | 3/38 |

| Growth | ||

| Low weight | 32% | 12/38 |

| Microcephaly | 32% | 12/38 |

| Neurology | ||

| Hypotonia | 76% | 29/38 |

| Epilepsy | 16% | 6/38 |

| Movement disorder (including spasticity) | 45% | 17/38 |

| Behavior problems | 53% | 20/38 |

| Brain MRI | ||

| Corpus callosum hypoplasia | 35% | 13/37 |

| Cortical malformation | 11% | 4/37 |

| Ventricular enlargement | 35% | 13/37 |

| Other | ||

| Skin abnormalities | 37% | 14/38 |

| Hyperlaxity | 37% | 14/38 |

| Visual problems | 34% | 13/38 |

| Hearing loss | 8% | 3/38 |

| Cleft lip or palate | 8% | 3/38 |

| Precocious puberty | 13% | 5/38 |

| Scoliosis | 11% | 4/38 |

Figure 2.

Facial Profiles of Females with De Novo DDX3X Mutations

Facial features of 30 of 38 females with a de novo variant in DDX3X. Common facial features include a long and/or hypotonic face (e.g., individuals 2, 4, 5, 12, 22, 32), a high and/or broad forehead (e.g., individuals 1, 7, 9, 23, 24, 26), a wide nasal bridge and/or bulbous nasal tip (e.g., individuals 11, 13, 15, 16), narrow alae nasi and/or anteverted nostrils (e.g., individuals 2, 8, 9, 12, 14, 18, 24, 27, 32, 35), and hypertelorism (e.g., individuals 5, 7, 8, 20, 27). Informed consent was obtained for all 30 individuals shown. The individual numbers correspond to the numbers mentioned in Tables 1 and S1.

DDX3X is known as one of the genes that are able to escape X inactivation.14,15 X-linked dominant conditions often show a remarkable variability among affected females which in particular holds true for genes that escape X inactivation.9,16 It is known that most of the transcripts escaping X inactivation are not fully expressed from the inactivated X chromosome, which means that the escape is often partial and incomplete.9 Based on this, phenotypic severity might be influenced by the amount of gene expression of DDX3X in females, which could be affected by possibly skewed X inactivation or incompleteness of the escape. Different expression of DDX3X in different tissues could also be a contributing factor. To further explore the possible skewing of X inactivation, we determined X inactivation via the androgen receptor gene (AR) methylation assay17 on DNA from lymphocytes in 15 females. We found an almost complete skewing (>95%) of X inactivation in seven individuals and random skewing in the remainder. This is more than would be expected by chance, because it is known that a high degree of skewing of X inactivation is a statistically rare event in young women.18 However, in our affected females, there is no evidence of correlation of skewing of X inactivation with disease severity.

Given the high frequency (1%–2%) of DDX3X mutations in females with unexplained ID, we sought to determine whether males carry deleterious alleles. We identified no de novo variants in DDX3X males in any of our cohorts. However, upon sequencing of the X chromosome (X-exome) of ID-affected families with apparent X-linked inheritance pattern,7 we identified two families with segregating missense variants in DDX3X. Moreover, one additional family was identified by diagnostic whole exome sequencing in Antwerp, Belgium. In these three families, males with the DDX3X variant have borderline to severe ID and carrier females are unaffected. Pedigrees of these three families are shown in Figure S1, and a summary of the clinical features of the affected males is presented in Table S2. All three missense mutations were predicted to be deleterious by prediction programs PolyPhen-2 and SIFT (Table 1) and map within the helicase ATP-binding domain (Figure 2). With three-dimensional protein analysis, we could not discern any clear difference between the missense mutations found in affected males and the de novo mutations found in females that could possibly explain the gender-specific pathogenicity (Figure S2, Table S3). Although in the first two families with affected males the phenotype consisted mainly of intellectual disability, family 3 was more complex. The male proband had severe ID and various other features such as a dysplastic pulmonary valve, hypertonia, and strabismus. In this male a SNP-array analysis was performed, as well as DNA analysis of PTEN (MIM: 601728) and FMR1 (MIM: 309550) and methylation studies on Angelman syndrome (MIM: 105830), all without abnormalities. With exome sequencing no other candidate genes were found. His mother had recurrent miscarriages of unknown gender. A second initially viable pregnancy was terminated because of ultrasound anomalies that had also been noted in the proband, including a thickened nuchal fold and absent nasal bone. After termination of the pregnancy, the male fetus was tested and found to have the same missense mutation in DDX3X as his brother. Sequencing of other family members demonstrated that the mutation arose de novo in the proband’s mother. X-inactivation studies in this mother demonstrated a random X-inactivation pattern (68/32). X-inactivation studies in female carriers in the other families showed that in family 1, the obligate carrier female (II-2) had highly skewed X inactivation (>95%), whereas X-inactivation studies in family 2 were not informative.

None of the three DDX3X variants found in these families with affected males were reported in the ExAC database or in the Exome Variant Server (ESP), nor was one of the de novo variants found in females reported in these databases. Moreover, none of the DDX3X mutations identified in males were detected in affected females. As far as we are aware, in addition to the de novo missense mutation identified in family 3, no other de novo mutations in DDX3X are reported in healthy individuals or control cohorts. We downloaded all variants from the ExAC database, containing exome data of 60,706 individuals, and calculated per gene the number of missense and synonymous variants. These numbers were then normalized by dividing through the total number of possible missense and synonymous variants per gene. The ratio of corrected missense over synonymous variants was then used as a measure for tolerance of the gene to normal variation, similarly as was done previously.19 When genes were ranked according to their tolerance score, DDX3X was among the most intolerant genes (1.09% of genes, rank 194 out of 17,856), showing that normal variation in this gene is extremely rare.

DDX3X encodes a conserved DEAD-box RNA helicase important in a variety of fundamental cellular processes that include transcription, splicing, RNA transport, and translation.20,21 DDX3X has been associated with many cellular processes, such as cell cycle control, apoptosis, and tumorigenesis.22,23 It is also thought to be an essential factor in the RNAi pathway24 and it is a key regulator of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, acting as a regulatory subunit of CSNK1E and stimulating its kinase activity.25

Notably, of the 35 different de novo variants, 19 alleles are predicted to give a loss-of-function effect. Antisense-based knockdown of the DDX3X-ortholog PL10 in zebrafish (72% identical, 78% similar) is already described and shows a reduced brain size and head size in zebrafish embryos at 2 days postfertilization (dpf).13 The missense changes in affected females were located in the same protein domain as the missense changes in affected males, so we explored the pathogenic mechanisms accounting for the differences in disease transmission and phenotype between affected females and affected males with DDX3X missense variants. We therefore employed a combination of in vitro and in vivo assays based on the known role of DDX3X in the regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling.25 Wnt signaling is a critical developmental pathway; the zebrafish is a tractable model in which to study Wnt output26–31 and to interrogate alleles relevant to neurocognitive traits.32 We tested several representative missense variants, including the female-specific de novo variants c.641T>C (p.Ile214Thr), c.977G>A (p.Arg326His), c.1126C>T (p.Arg376Cys), c.1520T>C (p.Ile507Thr), and c.1601G>A (p.Arg534His) as well as the inherited variants c.898G>T (p.Val300Phe), c.1052G>A (p.Arg351Gln), and c.1084C>T (p.Arg362Cys) identified in males. A variant from the Exome Variant Server (c.586G>A [p.Glu196Lys]) was chosen as a negative control (rs375996245; MAF < 0.002).

We first tested whether the missense variants identified in our ID cohort resulted in dominant effects by overexpressing either WT or mutant DDX3X human transcript in zebrafish embryos and examining the phenotype. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) were raised and mated as described.33 Embryos from ZDR strain fish were injected into the yolk with 1 nl of solution containing mRNA at the 1- to 2-cell stage using a Picospritzer III microinjector (Parker). The wild-type (WT) human DDX3X open reading frame (ORF) construct was obtained from the Ultimate ORF Collection (LifeTechnologies; clone ID: IOH13891), sequenced fully, and sub-cloned into the pCS2+ vector using Gateway LR clonase II- mediated cloning (LifeTechnologies). Capped mRNA was generated using linearized constructs as a template with the mMessage mMachine SP6 transcription kit (LifeTechnologies). Injection of 100 pg of WT or mutant DDX3X transcripts did not produce a discernible phenotype at 36 hr postfertilization (hpf) (n = 50–75 embryos/injection; repeated twice with masked scoring; Figure S3A) or at 72 hpf (not shown). To corroborate these data in a different system, we used a mammalian cell-based assay of canonical Wnt signaling (TOPFlash).34 In brief, HEK293T cells and mouse L-cells (both control and WNT3A expressing) were grown in 10% FBS/DMEM. WNT3A-containing media was prepared by incubating confluent L-cells with serum-free media for 24 hr and removing and filtering the media. This was subsequently used to stimulate transfected HEK293T cells. HEK293T cells at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well on 24-well plates were transfected with 1.025 μg total of DNA containing 0.5 μg of pGL4.18 TOPFLASH vector, 25 ng of renilla luciferase plasmid (pRL-SV40), and 0.5 μg of pCS2+ with or without DDX3X using XtremeGene9 (Roche). After 24 hr the media was removed and replaced with serum-free media collected as above from L-cells with and without WNT3A (MIM: 606359). After 24 hr, cells were harvested and luciferase activity measured by the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Results were normalized internally for each well to renilla luciferase activity and then to the unstimulated wells (conditioned with control L-cell media). Consistent with the in vivo result, transfection of expression constructs harboring DDX3X variants did not differ from WT in the modulation of WNT3A-β-catenin mediated luciferase activity (Figure S3B; triplicate wells with 3–5 biological replicates). Taken together, our results suggest that neither the female nor the male DDX3X variants produce detectable dominant changes in the context of Wnt signaling. These results are in line with the high number of de novo truncating mutations in females, suggesting haploinsufficiency as the most likely pathogenic mechanism. As a consequence, we pursued a loss-of-function paradigm.

Previous studies have shown that co-expression of a canonical Wnt ligand and DDX3X is necessary to produce a phenotype in vivo.25 Expression of either of the canonical Wnt ligands WNT3A or WNT8A (MIM: 606360) results in ventralization of zebrafish embryos that ranges from mild (hypoplasia of the eyes, which we term class I embryos) to moderate (absence of one or both eyes; class II), severe (loss of all anterior neural structures; class III), and radialized (class IV) phenotypes at 2 dpf.28 We recapitulated these defects by injecting increasing doses of human WNT3A or WNT8A mRNA into embryos (Figures 3A and 3B). Full-length human WNT3A and WNT8A ORFs were cloned into pCS2+ from the Ultimate ORF Collection (Clone ID WNT8A: IOH35591; Clone ID WNT3A: IOH80731). The WNT3A clone required site-directed mutagenesis to introduce a stop codon using primers (5′-ctgcaaggccgccaggcacTAGGGTGGGCGCGCCGA-3′ and its reverse complement). We selected a dose of WNT3A mRNA (200 fg), which produced a modest effect (15%–20% class I+II embryos, no class III or IV) and we co-injected it with progressively increasing concentrations of human DDX3X mRNA. At 2 dpf, we observed a dose-response curve concomitant with increasing doses of DDX3X (Figure 3D). At low doses of mutant DDX3X (15–20 pg/embryo), the ventralization phenotype produced by WNT3A is exacerbated, producing 40%–50% class I+II embryos, with a greater percentage in class II (10%–15%), indicative of augmented severity (Figure 3D).

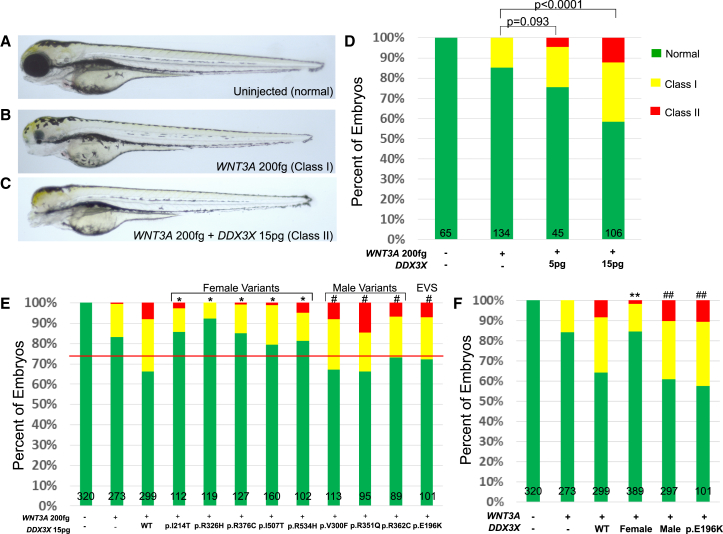

Figure 3.

The Effect of Wild-Type and Variant DDX3X mRNA on WNT3A-Mediated Ventralization

(A–C) Zebrafish embryos at 2 dpf either uninjected (A) or injected with human WNT3A without (B) or with (C) human DDX3X show a range of ventralized phenotypes. These were scored according to Kelly et al.28 as normal, class I, or class II ventralization. No injection condition resulted in severe ventralization (class III or IV).

(D) Co-injection of WNT3A and DDX3X shows an augmentation of WNT3A-mediated ventralization with increasing dose up to 15 pg.

(E) Individual variants of DDX3X were tested for their effect on increasing WNT3A-mediated ventralization using 200 fg of WNT3A mRNA and 15 pg of DDX3X mRNA per embryo (dose of maximal response from D). Scoring is the same as in (D). The female de novo variants and the male familial variants are shown together. The substitution p.Glu196Lys is a rare allele from the Exome Variant Server (EVS). The red horizontal line delineates a division between those variants that behave as “wild-type” (e.g., the male variants and p.Glu196Lys) and those that do not. All female de novo variants are significantly different from wild-type but not different from WNT3A alone. Male variants are significantly different from WNT3A alone but not different from DDX3X + WT. ∗p < 0.001 compared with WNT3A + wild-type DDX3X co-injection. #p < 0.0001 versus WNT3A alone.

(F) Graph illustrating the effect of combining the results from the female de novo variants and comparing to the male familial variants and to the p.Glu196Lys variant from the EVS. There is clear segregation of effect based on the source of the genetic variant. ∗∗p < 0.0001 versus WNT3A + wild-type DDX3X. ##p < 0.0001 versus WNT3A alone. For each graph, total (n) is shown at the bottom of each bar.

Because of the significant (p < 0.0001) augmentation of WNT3A-mediated ventralization at 15 pg of DDX3X, we next used this combination of doses to test the effect of the missense alleles on Wnt signaling. WNT3A mRNA (200 fg) was co-injected with 15 pg of WT or variant DDX3X mRNA, and we scored embryos for ventralization at 2 dpf. We found differential effects of the variants on ventralization (Figure 3E; triplicate experiments; pooled for the final result). All de novo variants tested were significantly different from WT (p < 0.001) and indistinguishable from WNT3A alone, suggesting that they all confer complete loss of function to DDX3X. By contrast, the control variant c.586G>A (p.Glu196Lys) resulted in phenotypes similar to WT. Notably, all three inherited variants found in the affected males were also indistinguishable from WT injected and each was statistically different from WNT3A alone (p < 0.0001). Given this apparent dichotomization of effect between female de novo and male inherited alleles, we tested whether pooling of results from the female versus male variants would exhibit a “class effect” separation between the two groups. We found this to be true; there was significant differential effect of the gender-specific sets of variants on Wnt signaling (Figure 3F).

Taken together, our in vivo testing of the nonsynonymous DDX3X mutations demonstrated marked alteration in Wnt-mediated ventralization for changes arising de novo in affected females. Our data also reinforce the notion that disruption of β-catenin signaling during neurodevelopment has profound consequences. Loss of Wnt signaling inhibits neuroblast migration, neural differentiation, and suppression of the development of the forebrain.35–38 Moreover, we previously reported that mutations in β-catenin contribute to ID in humans,39,40 and mutations in δ-catenin, some of which abrogate its biochemical interaction with β-catenin, can contribute to severe autism in females,32 strengthening further the link between Wnt signaling and human neurodevelopmental disorders.

DDX3X has recently been proposed as a candidate ID gene.13,41 Our data substantiate this hypothesis and suggest that mutated DDX3X is among the most common causes of simplex cases of intellectual disability in females. Our data also suggest that the genetic architecture of DDX3X-mediated pathology in males is different. All detected male alleles were inherited from unaffected mothers, suggesting either a gender-specific buffering effect or a milder effect of those inherited alleles on protein function. Both our in vivo and our in vitro studies indicate that none of the tested alleles (male or female) confer dominant effects and that the male alleles are indistinguishable from WT in our system. Given that human genetics and computational predictions support the causality of these alleles in the families studied, we speculate that the effect of these alleles is beyond the dynamic range of our assays and thus could not be detected; a substantially larger assay of embryos might detect a signal, although the transient nature of our system will always be limited at detecting mild allele effects. Alternatively, the mechanism of the male-derived alleles might be qualitatively different from the de novo female variants and reflective of the complex biology of DDX3X. Of note, we found that increased amounts of wild-type DDX3X ameliorated the Wnt3a-induced ventralization phenotype (Figure S4B), an observation that we reproduced with Wnt8a, another β-catenin-dependent ligand (Figure S4A) and our TOPFlash reporter assay (Figure S3B). This bimodal activity of DDX3X has been intimated previously by Cruciat et al., in which knockdown of DDX3X caused loss of WNT3A signaling that was restored by transfection with WT construct whereas overexpression alone resulted in decreased WNT3A signaling.25 We reproduced this latter finding when solely overexpressing DDX3X in HEK293 cells (Figure S3B).

Summarized, these data suggest that DDX3X is dosage sensitive and might have a differential activity in females than in males. Contribution of the DDX3X homolog at the Y chromosome, DDX3Y (MIM: 400010), to phenotypic variability is unlikely.42 DDX3X and DDX3Y have 92% amino acid sequence in common14 but DDX3Y is translated only in spermatocytes and is essential for spermatogenesis.43,44 Deletions or mutations of DDX3Y cause spermatogenic failure but are not associated with cognitive dysfunction or other abnormalities.44,45

In conclusion, de novo variants in DDX3X are a frequent cause of intellectual disability, affecting 1%–3% of all so far unexplained ID in females. Although no de novo mutations were identified in males, we found missense variants in DDX3X in males from three families with ID suggestive of X-linked recessive inheritance. Our phenotypic read out in zebrafish shows a gender difference in identified variants with a loss-of-function effect of all tested de novo mutations on the Wnt pathway. The differential activity possibly indicates a dose-dependent effect of DDX3X expression in the context of functional mosaic females versus one-copy males, which reflects the complex biological nature of pathogenic DDX3X variants.

Conflicts of Interest

J.J., M.T.C., K.R., P.R., K.G.M., and E.H. are employees of GeneDx. W.K.C. is a consultant to BioReference Laboratories.

Acknowledgments

We thank the families for their contribution. Drs. Jillian Parboosingh, Francois Bernier, and Ryan Lamont contributed to the study design, data interpretation, and X-inactivation studies of individual 8. Drs. Concetta Barone and Paolo Bosco were instrumental for clinical evaluation and X-inactivation studies in individual 13. Miriam Uppill provided technical assistance with investigations in family 1. This work was supported by a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw grant 907-00-365 to T.K.), the Italian Ministry of Health and ‘5 per mille’ funding (C.R.), a grant from the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation (A.M.I.), a NIH Training Grant (5T32HD060558-04 to E.C.M.), German Ministry of Education and Research (01GS08166 to N.D.D. and A.R.), the EU FP7 project GENCODYS (grant number 241995 to V.M.K.), Australian NH&MRC grants 628952 and 1041920 to J.G., support from the Simons Foundation (W.K.C.), Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinical Scientist Development Award (M.C.K.), a grant from the Marguerite-Marie Delacroix Foundation (A.V.D.), and FWO-Flanders (H.V.E. and F.K.). B.L. is a senior clinical investigator supported by Fund for Scientific Research Flanders and holds an ERC starting grant. Acknowledgments of the DDD Study are included in the Supplemental Data.

Published: July 30, 2015

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include four figures, three tables, and Supplemental Acknowledgments and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.07.004.

Contributor Information

Nicholas Katsanis, Email: nicholas.katsanis@duke.edu.

Tjitske Kleefstra, Email: tjitske.kleefstra@radboudumc.nl.

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

ExAC Browser, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) Exome Variant Server, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

PolyPhen-2, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/

SIFT (v.1.03), http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Roeleveld N., Zielhuis G.A., Gabreëls F. The prevalence of mental retardation: a critical review of recent literature. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1997;39:125–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leonard H., Wen X. The epidemiology of mental retardation: challenges and opportunities in the new millennium. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2002;8:117–134. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maulik P.K., Mascarenhas M.N., Mathers C.D., Dua T., Saxena S. Prevalence of intellectual disability: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011;32:419–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Naarden Braun K., Christensen D., Doernberg N., Schieve L., Rice C., Wiggins L., Schendel D., Yeargin-Allsopp M. Trends in the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, intellectual disability, and vision impairment, metropolitan Atlanta, 1991-2010. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0124120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schalock R.L., Borthwick-Duffy S.A., Bradley V.J., Buntinx W.H.E., Coulter D.L., Craig E.M., Gomez S.C., Lachapelle Y., Luckasson R., Reeve A. American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities; 2010. Intellectual Disability: Definition, Classification, and Systems of Supports. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piton A., Redin C., Mandel J.L. XLID-causing mutations and associated genes challenged in light of data from large-scale human exome sequencing. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;93:368–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu H., Haas S.A., Chelly J., Van Esch H., Raynaud M., de Brouwer A.P., Weinert S., Froyen G., Frints S.G., Laumonnier F. X-exome sequencing of 405 unresolved families identifies seven novel intellectual disability genes. Mol. Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.193. Published online February 3, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dobyns W.B., Filauro A., Tomson B.N., Chan A.S., Ho A.W., Ting N.T., Oosterwijk J.C., Ober C. Inheritance of most X-linked traits is not dominant or recessive, just X-linked. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2004;129A:136–143. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morleo M., Franco B. Dosage compensation of the mammalian X chromosome influences the phenotypic variability of X-linked dominant male-lethal disorders. J. Med. Genet. 2008;45:401–408. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.058305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neveling K., Feenstra I., Gilissen C., Hoefsloot L.H., Kamsteeg E.J., Mensenkamp A.R., Rodenburg R.J., Yntema H.G., Spruijt L., Vermeer S. A post-hoc comparison of the utility of sanger sequencing and exome sequencing for the diagnosis of heterogeneous diseases. Hum. Mutat. 2013;34:1721–1726. doi: 10.1002/humu.22450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Ligt J., Willemsen M.H., van Bon B.W., Kleefstra T., Yntema H.G., Kroes T., Vulto-van Silfhout A.T., Koolen D.A., de Vries P., Gilissen C. Diagnostic exome sequencing in persons with severe intellectual disability. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1921–1929. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Retterer K., Scuffins J., Schmidt D., Lewis R., Pineda-Alvarez D., Stafford A., Schmidt L., Warren S., Gibellini F., Kondakova A. Assessing copy number from exome sequencing and exome array CGH based on CNV spectrum in a large clinical cohort. Genet. Med. 2014 doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.160. Published online November 6, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study Large-scale discovery of novel genetic causes of developmental disorders. Nature. 2015;519:223–228. doi: 10.1038/nature14135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lahn B.T., Page D.C. Functional coherence of the human Y chromosome. Science. 1997;278:675–680. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cotton A.M., Price E.M., Jones M.J., Balaton B.P., Kobor M.S., Brown C.J. Landscape of DNA methylation on the X chromosome reflects CpG density, functional chromatin state and X-chromosome inactivation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015;24:1528–1539. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carrel L., Willard H.F. X-inactivation profile reveals extensive variability in X-linked gene expression in females. Nature. 2005;434:400–404. doi: 10.1038/nature03479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen R.C., Zoghbi H.Y., Moseley A.B., Rosenblatt H.M., Belmont J.W. Methylation of HpaII and HhaI sites near the polymorphic CAG repeat in the human androgen-receptor gene correlates with X chromosome inactivation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1992;51:1229–1239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Busque L., Mio R., Mattioli J., Brais E., Blais N., Lalonde Y., Maragh M., Gilliland D.G. Nonrandom X-inactivation patterns in normal females: lyonization ratios vary with age. Blood. 1996;88:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilissen C., Hehir-Kwa J.Y., Thung D.T., van de Vorst M., van Bon B.W., Willemsen M.H., Kwint M., Janssen I.M., Hoischen A., Schenck A. Genome sequencing identifies major causes of severe intellectual disability. Nature. 2014;511:344–347. doi: 10.1038/nature13394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdelhaleem M. RNA helicases: regulators of differentiation. Clin. Biochem. 2005;38:499–503. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garbelli A., Beermann S., Di Cicco G., Dietrich U., Maga G. A motif unique to the human DEAD-box protein DDX3 is important for nucleic acid binding, ATP hydrolysis, RNA/DNA unwinding and HIV-1 replication. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Q., Zhang P., Zhang C., Wang Y., Wan R., Yang Y., Guo X., Huo R., Lin M., Zhou Z., Sha J. DDX3X regulates cell survival and cell cycle during mouse early embryonic development. J. Biomed. Res. 2014;28:282–291. doi: 10.7555/JBR.27.20130047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schröder M. Human DEAD-box protein 3 has multiple functions in gene regulation and cell cycle control and is a prime target for viral manipulation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;79:297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasim V., Wu S., Taira K., Miyagishi M. Determination of the role of DDX3 a factor involved in mammalian RNAi pathway using an shRNA-expression library. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e59445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cruciat C.M., Dolde C., de Groot R.E., Ohkawara B., Reinhard C., Korswagen H.C., Niehrs C. RNA helicase DDX3 is a regulatory subunit of casein kinase 1 in Wnt-β-catenin signaling. Science. 2013;339:1436–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.1231499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellipanni G., Varga M., Maegawa S., Imai Y., Kelly C., Myers A.P., Chu F., Talbot W.S., Weinberg E.S. Essential and opposing roles of zebrafish β-catenins in the formation of dorsal axial structures and neurectoderm. Development. 2006;133:1299–1309. doi: 10.1242/dev.02295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caneparo L., Huang Y.-L., Staudt N., Tada M., Ahrendt R., Kazanskaya O., Niehrs C., Houart C. Dickkopf-1 regulates gastrulation movements by coordinated modulation of Wnt/β catenin and Wnt/PCP activities, through interaction with the Dally-like homolog Knypek. Genes Dev. 2007;21:465–480. doi: 10.1101/gad.406007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly C., Chin A.J., Leatherman J.L., Kozlowski D.J., Weinberg E.S. Maternally controlled (beta)-catenin-mediated signaling is required for organizer formation in the zebrafish. Development. 2000;127:3899–3911. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.18.3899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly G.M., Erezyilmaz D.F., Moon R.T. Induction of a secondary embryonic axis in zebrafish occurs following the overexpression of beta-catenin. Mech. Dev. 1995;53:261–273. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar S., Žigman M., Patel T.R., Trageser B., Gross J.C., Rahm K., Boutros M., Gradl D., Steinbeisser H., Holstein T. Molecular dissection of Wnt3a-Frizzled8 interaction reveals essential and modulatory determinants of Wnt signaling activity. BMC Biol. 2014;12:44. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-12-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lekven A.C., Thorpe C.J., Waxman J.S., Moon R.T. Zebrafish wnt8 encodes two wnt8 proteins on a bicistronic transcript and is required for mesoderm and neurectoderm patterning. Dev. Cell. 2001;1:103–114. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turner T.N., Sharma K., Oh E.C., Liu Y.P., Collins R.L., Sosa M.X., Auer D.R., Brand H., Sanders S.J., Moreno-De-Luca D. Loss of δ-catenin function in severe autism. Nature. 2015;520:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature14186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westerfield M. University of Oregon Press; Eugene, OR: 1995. The Zebrafish Book. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu W., Glinka A., Delius H., Niehrs C. Mutual antagonism between dickkopf1 and dickkopf2 regulates Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:1611–1614. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00868-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andoniadou C.L., Signore M., Young R.M., Gaston-Massuet C., Wilson S.W., Fuchs E., Martinez-Barbera J.P. HESX1- and TCF3-mediated repression of Wnt/β-catenin targets is required for normal development of the anterior forebrain. Development. 2011;138:4931–4942. doi: 10.1242/dev.066597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Najm F.J., Lager A.M., Zaremba A., Wyatt K., Caprariello A.V., Factor D.C., Karl R.T., Maeda T., Miller R.H., Tesar P.J. Transcription factor-mediated reprogramming of fibroblasts to expandable, myelinogenic oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:426–433. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mentink R.A., Middelkoop T.C., Rella L., Ji N., Tang C.Y., Betist M.C., van Oudenaarden A., Korswagen H.C. Cell intrinsic modulation of Wnt signaling controls neuroblast migration in C. elegans. Dev. Cell. 2014;31:188–201. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang S., Li J., Lea R., Vleminckx K., Amaya E. Fezf2 promotes neuronal differentiation through localised activation of Wnt/β-catenin signalling during forebrain development. Development. 2014;141:4794–4805. doi: 10.1242/dev.115691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuechler A., Willemsen M.H., Albrecht B., Bacino C.A., Bartholomew D.W., van Bokhoven H., van den Boogaard M.J., Bramswig N., Büttner C., Cremer K. De novo mutations in beta-catenin (CTNNB1) appear to be a frequent cause of intellectual disability: expanding the mutational and clinical spectrum. Hum. Genet. 2015;134:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00439-014-1498-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tucci V., Kleefstra T., Hardy A., Heise I., Maggi S., Willemsen M.H., Hilton H., Esapa C., Simon M., Buenavista M.T. Dominant β-catenin mutations cause intellectual disability with recognizable syndromic features. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:1468–1482. doi: 10.1172/JCI70372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rauch A., Wieczorek D., Graf E., Wieland T., Endele S., Schwarzmayr T., Albrecht B., Bartholdi D., Beygo J., Di Donato N. Range of genetic mutations associated with severe non-syndromic sporadic intellectual disability: an exome sequencing study. Lancet. 2012;380:1674–1682. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61480-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sekiguchi T., Iida H., Fukumura J., Nishimoto T. Human DDX3Y, the Y-encoded isoform of RNA helicase DDX3, rescues a hamster temperature-sensitive ET24 mutant cell line with a DDX3X mutation. Exp. Cell Res. 2004;300:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ditton H.J., Zimmer J., Kamp C., Rajpert-De Meyts E., Vogt P.H. The AZFa gene DBY (DDX3Y) is widely transcribed but the protein is limited to the male germ cells by translation control. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004;13:2333–2341. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Foresta C., Ferlin A., Moro E. Deletion and expression analysis of AZFa genes on the human Y chromosome revealed a major role for DBY in male infertility. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1161–1169. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.8.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferlin A., Moro E., Rossi A., Dallapiccola B., Foresta C. The human Y chromosome’s azoospermia factor b (AZFb) region: sequence, structure, and deletion analysis in infertile men. J. Med. Genet. 2003;40:18–24. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.