Abstract

Background

Isoflurane induces cell death in neurons undergoing synaptogenesis via increased production of pro-brain derived neurotrophic factor (proBDNF) and activation of post-synaptic p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR). Astrocytes express p75NTR but their role in neuronal p75NTR mediated cell death remains unclear. We investigated whether astrocytes have the capacity to buffer increases in proBDNF and protect against isoflurane/p75NTR neurotoxicity.

Methods

Cell death was assessed in day-in-vitro (DIV) 7 mouse primary neuronal cultures alone or in co-culture with age-matched or DIV 21 astrocytes with propidium iodide 24 hours following 1 hour exposure to 2% isoflurane or recombinant proBDNF. Astrocyte-targeted knockdown of p75NTR in co-culture was achieved with small interfering RNA and astrocyte-specific transfection reagent and verified with immunofluorescence microscopy. proBDNF levels were assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Each experiment used 6–8 replicate cultures/condition, and was repeated at least three times.

Results

Exposure to isoflurane significantly (p<0.05) increased neuronal cell death in primary neuronal cultures (1.5±0.7 fold, mean±SD) but not in co-culture with DIV 7 (1.0±0.5 fold) or DIV 21 astrocytes (1.2±1.2 fold). Exogenous proBDNF dose dependently induced neuronal cell death in both primary neuronal and co-cultures, an effect enhanced by astrocyte p75NTR inhibition. Astrocyte-targeted p75NTR knockdown in co-cultures increased media proBDNF (1.2±0.1 fold) and augmented isoflurane induced neuronal cell death (3.8±3.1 fold).

Conclusions

The presence of astrocytes provides protection to growing neurons by buffering elevated levels of proBDNF induced by isoflurane. These findings may hold clinical significance for the neonatal and injured brain where elevated levels of proBDNF impair neurogenesis.

Introduction

Anesthetic neurotoxicity, characterized in animal models by widespread induction of neuronal cell death, disruption in synapse formation and stabilization, and impairment of neurocognitive development, appears to occur primarily during the period of active synaptogenesis.1 A primary mechanism contributing to anesthetic neurotoxicity during this period has been attributed to modulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF),2, 3 a central regulator of neurogenesis,4 synaptogenesis 5 and neurotransmission.6 In addition to playing a critical role in normal brain development 7, BDNF signaling is instrumental to learning and long-term memory consolidation8, 9 and repair of the brain and spinal cord following injury in the adult.10, 11 Whether BDNF induces pro-death or pro-survival signaling in post-synaptic neurons is determined by the relative balance of the pro-neurotrophin form of BDNF (proBDNF) and the proteolytically cleaved mature form. Post-synaptic signaling of mature BDNF promotes neurite formation and stabilization of existing synapses via activation of tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB), whereas proBDNF signaling induces post-synaptic neuronal death via activation of p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR, or low affinity nerve growth factor receptor). Anesthetic neurotoxicity occurs via decreased proteolytic cleavage of proBDNF,2 leading to augmentation of post-synaptic proBDNF/p75NTR binding, resulting in disruption of synaptogenesis and induction of post-synaptic neuronal death. This observation has generated concern about potential effects of volatile anesthetic exposure on brain development in neonates and the possibility of neurocognitive sequelae, but may also theoretically impact synaptogenesis and neurogenesis in the normal and/or injured adult brain.

Growth, maintenance and repair of the neuronal network, in both neonates and adults, are coordinated by resident astrocytes,12, 13 specialized glia that are the most abundant cell in the human brain. In addition to their role in neuronal housekeeping and protection, astrocytes have been shown to play a significant role in neurotransmission, such that the association between astrocyte processes and neuronal synapses has been coined the “tripartite synapse.”13 Astrocytes modulate synaptic transmission via glutamate uptake,14 and are central to synapse formation and stabilization.15, 16 An individual astrocyte may contact up to 100,000 neurons17 serving to integrate signals within the neuronal network. Moreover, astrocytes themselves communicate with adjacent astrocytes via intercellular gap junctions to function as a coordinated syncytium,18 providing an additional astrocyte-dependent layer of neuronal regulation. More recently astrocytes have also been shown to express p75NTR, which can bind and internalize proBDNF, removing it from the extracellular space.19 However, the role of astrocytes in BDNF-mediated neuronal signaling has not been defined, and whether astrocytes have the capacity to functionally buffer increases in pro-BNDF and protect adjacent neurons from proBDNF/p75NTR-mediated cell death has not been investigated. In the present study we utilized primary neuronal, astrocyte and neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures to test the hypothesis that astrocytes mitigate increases in proBDNF via astrocyte-dependent p75NTR binding, resulting in a reduction in BDNF/p75NTR-mediated neuronal cell death.

Materials and Methods

Animal Protocols

All experiments were performed according to protocols approved by the Stanford University Animal Care and Use Committee (Stanford, CA, USA) and follow the National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal welfare.

Cell Cultures

Relatively pure astrocyte cultures were prepared from postnatal day 1–3 Swiss Webster mice.20 Briefly, after euthanasia, brains were removed in a sterile field and cortices were freed of meninges in ice-cold Eagle’s minimal essential medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) and incubated in 0.05% trypsin/EDTA (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 30 min at 37°C followed by mechanical dissociation. Neocortical cells were plated at a density of 2 hemispheres/10 ml Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Gibco) with 10% equine serum (ES, HyClone, GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, Utah), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone) and 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (Sigma Chemicals, St Louis, MO, USA).

Relatively pure neuronal cultures were prepared from cortices of embryonic day 15 or 16 mice.20 Cortices were collected in ice-cold Eagle’s minimal essential medium, digested with 0.05% trypsin/EDTA for 15 min at 37°C, mechanically dissociated, then plated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 26 mM NaHCO3 (Sigma Chemicals), 24 mM glucose (Sigma Chemicals), 5% FBS and 5% ES. On day in vitro #2, (DIV 2) media was exchanged with glial-conditioned medium, same composition as neuronal plating medium but lacking FBS, incubated with DIV 14 primary glial cultures for 7 days, then filtered and stored at −20°C until use. Prior to use conditioned medium was supplemented with B-27 (2%, Gibco) and cytosine arabinoside (3 μM, Sigma-Aldrich), the later added to inhibit glial proliferation.

For co-culture experiments two culture conditions were utilized. Method 1: Neurons from a single dissection were plated on near-confluent astrocyte cultures (DIV 14).21 Method 2: To assess whether age-matched astrocytes also protect neurons from isoflurane toxicity, co-cultures were prepared from a single neocortical dissection in a similar fashion to neuronal cultures but increasing the serum to 7.5% each of FBS and ES, adding 5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor and omitting B-27 and cytosine arabinoside. Neuronal, astrocyte and neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures were maintained in a 37°C humidified incubator with 5% CO2 in room air atmosphere.

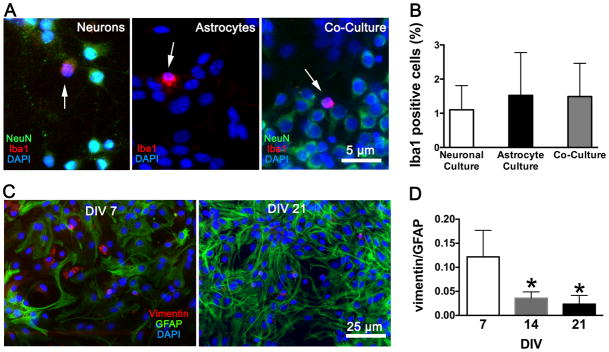

Cultures were characterized by quantitating the cell types immunohistochemically using neuronal, astrocyte, and microglial markers (see Fig. 1A, B). Microglial content in our astrocyte cultures ranged from 0% to 4.6% (average 1.5 ± 1.3%) and no detectable neurons. Our neuronal culture microglial content ranged from 0.4% to 1.5% (average 1.1 ± 0.7%) and <1% astrocytes, while neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures ranged from 0.5% to 3.1% (average 1.5 ± 1.0%) microglial content. The relative maturity of our astrocytes was assessed using markers for immature (vimentin) and mature (glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP) astrocytes, and showed a decline in the ratio of vimentin to GFAP with DIV (see Fig. 1C, D).

Figure 1.

Characterization of the three types of cultures. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of neuronal cultures, astrocyte cultures, and co-cultures with the microglial marker Iba1 (red), co-stained with the neuronal marker NeuN (green) and the nuclear stain DAPI (blue). Arrows identify microglia. (B) Quantitation of microglia in the cell cultures. (C) Immunofluorescence staining of astrocyte cultures at day-in-vitro (DIV) 7 and 21 with the immature astrocyte marker vimentin (red), the mature astrocyte marker GFAP (green), and DAPI (blue). (D) The ratio of vimentin to GFAP at 7, 14 and 21 DIV. Mean ± SD, n = 6 cultures per group, two fields averaged per culture; * = P < 0.05 versus DIV 7. NeuN = neuronal nuclei; DAPI = 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GFAP = glial fibrillary acidic protein.

Experimental Protocols

Primary neuronal and mixed neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures at neuronal DIV 7 were exposed for 1 hr to either 2% isoflurane (assessed with a Datex 245 Airway Gas Monitor, Datex Corp., North Clearwater, Fl, USA) in pre-mixed carrier gas (5% C02, 21% O2, balance N2), or to carrier gas alone. Gas flow was maintained at a rate of 2 L/min in a sealed, humidified incubator at 37°C. Neurons were assessed for cell death 24 hrs following isoflurane exposure. In additional experiments, isoflurane-induced neuronal cell death was assessed in primary neuronal cultures following application of conditioned medium from neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures, in co-cultures following astrocyte-targeted knockdown of p75NTR, and in co-cultures with and without the astrocyte-glutamate transporter inhibitor dihydrokainic acid (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK). Finally, neuronal cell death was assessed in neuronal, astrocyte and neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures 24 hrs following application of recombinant proBDNF (1–100 pg/ml, R+D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) plus protease inhibitor (diluted to 1X, G-Biosciences, St. Louis, MO), with and without the p75NTR inhibitor trans-activating transcriptional activator peptide 5 (TAT-Pep5, 10 μM, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Assays for Neuronal Cell Death

Neuronal viability in primary neuronal cultures was assessed after staining with Hoechst 33342 (5 μM, Sigma Chemicals) and propidium iodide (PI, 5 μM, Sigma Chemicals). PI stains dead cells while Hoescht is a cell-permeant nucleic acid stain that labels nuclei of both live and dead cells. PI-positive cells were manually counted by a blinded investigator, while numbers of Hoechst-positive cells were calculated using an automated macro (Image J, v1.49b, National Institutes of Health, USA). PI-positive and Hoechst-positive cells were counted in 3 microscopic fields per well at 200X magnification. The number of PI-positive cells was expressed as a percent of the total number of cells. In co-cultures, to neurons were differentiated from astrocytes using fluorescence immunocytochemistry with antibody specific for neuronal nuclei (NeuN) (described in further detail below in “Fluorescence Immunocytochemistry”). Dead neurons in co-cultures were identified as double-positive for PI and NeuN, and expressed as a percent of the total number of NeuN positive cells. Immunofluorescence was visualized with an epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 200M, Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany) at 200X magnification.22

Astrocyte-targeted p75NTR Knockdown

p75NTR messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein expression were assessed in primary astrocyte cultures by reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and fluorescence immunocytochemistry (below), respectively, 24 hrs following transfection with small interfering RNA (siRNA) against p75NTR (30 pmol/well, Silencer Select cat. #4390771, Life Technologies) or negative mismatch control (cat. #AM4615, Life Technologies). Transfection was achieved using Lipofectamine™-2000 (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfection with Lipofectamine™ reagents has been demonstrated23 to preferentially target astrocytes in neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures. In the present study we verified astrocyte-specific targeting in co-cultures using a reporter plasmid (30 pmol/well pDS-Red2-N1, Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA, USA), assessed with fluorescence immunocytochemistry 24 hrs following transfection. p75NTR protein expression was then assessed in neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures 24 hrs following transfection with p75NTR siRNA (30 pmol/well).

Fluorescence Immunocytochemistry

Fluorescence immunocytochemistry was performed on cell cultures in 24-well plates.22 Briefly, cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature and nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% normal goat serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 hr. Cells were then incubated with primary antibody to the neuronal marker NeuN (1:500, cat. #mab377, EMD Millipore, Billarica, MA), the astrocyte markers GFAP (1:500, cat #ab7260, Abcam) and vimentin (1:500 cat #ab8978, Abcam) and/or the microglial marker Iba1 (1:500, cat #ab178680, Abcam) overnight at 4°C. Cells were washed and subsequently incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 nm- or 594 nm-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) for 1 hr. Cells were counterstained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (0.5 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), a cell-permeant nuclear dye, for total cell count.

Real Time-quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol® (Life Technologies) from cultures 24 hrs following transfection. Reverse transcription was performed using the TaqMan® MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit for total RNA (Life Technologies).24 Predesigned primer/probes for polymerase chain reaction were obtained from Life Technologies for mouse p75NTR (#Mm01309638) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (#Mm99999915) mRNA. Real time-quantitative polymerase chain reaction was conducted using the TaqMan® Assay Kit (Life Technologies).24 Measurements for p75NTR mRNA were normalized to within-sample glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (ΔCt), and comparisons were calculated as the inverse log of the ΔΔCT from the mean of the control treatment group.25

Assay for proBDNF in Media

Concentrations of proBDNF in culture media were assessed before and immediately following isoflurane exposure, with and without transfection with p75NTR siRNA 24 hrs prior, by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer’s directions (cat #BEK-2217-2P, Biosenis, Thebarton, South Australia, Australia). Absorbance at 450 nm was measured via microplate reader (Versamax, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Statistics

All cultures were inspected microscopically prior to randomized assignment to experimental treatment, and data collection and analysis were performed blinded to treatment group. No data were excluded from inclusion in the final analysis. Sample sizes were determined from previous experience using these cell cultures.21 All data reported are representative of at least three independent experiments with n = 6–8 cultures per treatment, using 2–3 images per culture averaged. proBDNF ELISA data is representative of at least three independent experiments, with n = 12 cultures per treatment. All data are reported as means ± SD. For comparisons between two groups, statistical difference was determined by unpaired, two-tailed student’s t-test using Prism 6.0d software (Graphpad, La Jolla, CA, USA). For comparisons between multiple groups a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc comparison of all means to the control group (for proBDNF and dihydrokainate dose-response curves), or post-hoc comparison of all means to all other means (for proBDNF ELISA measurements) using Prism 6.0d software. In all analyses, a P-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

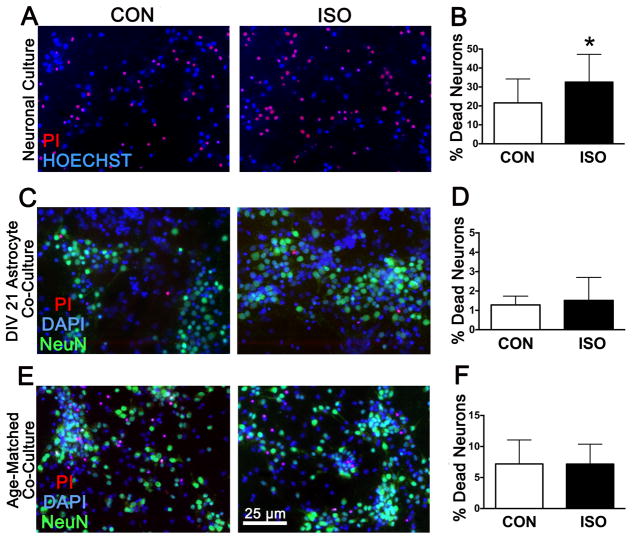

Isoflurane induces neuronal cell death in neuronal cultures but not in neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures

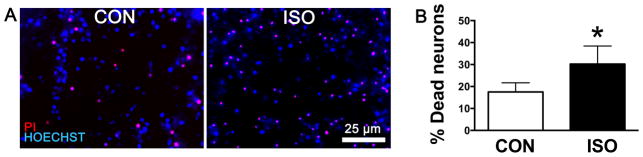

A 1 hr exposure to 2% isoflurane induced a significant increase in cell death (PI positive cells) in primary neuronal cultures (Fig. 2A, B). However, DIV 7 neurons growing in the presence of either DIV 21 astrocytes (Fig. 2C, D) or age-matched astrocytes (Fig. 2E, F) were protected from the effect of the same isoflurane exposure. This finding demonstrates that the observed protection from isoflurane neurotoxicty afforded by astrocytes occurred independently of the relative maturity of the astrocytes from DIV 7 to 21.

Figure 2.

Isoflurane exposure in primary neuronal and neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures. (A, B) Fluorescent staining of dead neurons with propidium iodide (PI, red) and live neurons with Hoechst (blue) in DIV 7 neuronal cultures 24 hrs after a 1 hr exposure to 2% isoflurane (ISO) or exposure to carrier gas exposure alone, (CON). (C–F) Co-cultures of neurons with DIV 21 or DIV 7 (age matched) astrocytes were immunostained for the neuronal marker NeuN (green) and stained with DAPI and PI. Dead neurons are identified as triple-positive for PI, NeuN and DAPI (blue), live neurons double positive for NeuN and DAPI. Neuronal death does not increase following isoflurane exposure when astrocytes are present. (E–F) In age-matched co-cultures baseline (CON) levels of neuronal cell death are higher than in co-culture with mature astrocytes (D), but lower than in neuronal cultures (B). Graphs are representative of data from three independent experiments each with n = 6 cultures per treatment, three fields averaged per culture; mean ± SD, * = P < 0.05 versus control. NeuN = neuronal nuclei; DAPI = 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Next, to test whether this effect was due to a secreted factor specific to neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures, the normal glia-conditioned media used in neuronal cultures was replaced with freshly harvested co-culture conditioned media 1 hr prior to isoflurane exposure. Media replacement did not result in any significant protection of neurons from isoflurane toxicity (see Fig. 3A, B), suggesting that the protective effect of astrocytes was dependent on the physical presence of astrocytes. No differences in the total numbers of neurons were observed between treatment groups (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Isoflurane exposure of neuronal cultures after replacement of media with conditioned media from co-cultures. (A) Micrographs of neuronal cultures stained with propidium iodide (PI, red) and Hoechst (blue) to identify dead and live neurons; quantitation of percent dead neurons (B). Graph is representative of data from three independent experiments each with n = 6 cultures per treatment, three fields averaged per culture; mean ± SD, * = P < 0.05 versus control. ISO = 1 hr 2% isoflurane treatment; CON = control carrier gas treatment.

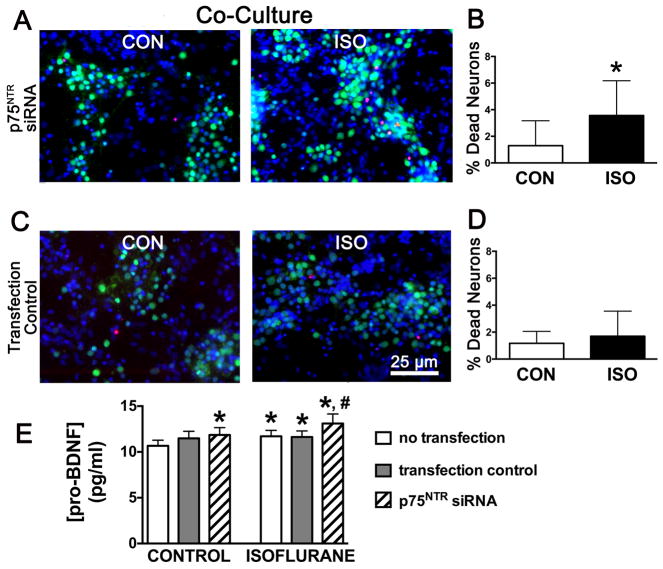

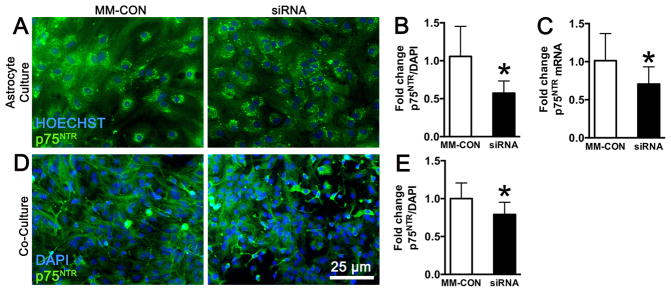

Astrocyte p75NTR knockdown in co-culture results in increased neuronal cell death from isoflurane

p75NTR protein and mRNA expression in primary astrocyte cultures was significantly reduced 24 hrs following transfection with p75NTR siRNA relative to mismatch control sequence using the transfection agent Lipofectamine™-2000 (Fig. 4A–C). Co-cultures transfected with reporter plasmid using Lipofectamine™-2000 resulted in preferential targeting of astrocytes, with <2% transfected cells identified as neurons. Co-cultures transfected with p75NTR siRNA using this method also showed a significant decrease in p75NTR protein expression (Fig. 4D, E), however to a smaller degree relative to transfection in primary astrocyte culture alone (Fig 4B), consistent with preferential knockdown in astrocytes. Transfection with p75NTR siRNA 24 hrs prior to isoflurane exposure resulted in a significant increase in neuronal cell death (Fig. 5A, B) relative to control transfection (Fig. 5C, D), suggesting that astrocyte p75NTR expression contributed to neuronal protection. Treatment with either p75NTR siRNA or isoflurane alone resulted in a modest increase in proBDNF levels in co-culture media (Fig. 5E). However combined treatment with both p75NTR siRNA and isoflurane resulted in a further increase in proBDNF levels versus either treatment alone (Fig. 5E bar furthest right). Together with the observation that only combined treatment resulted in increased neuronal cell death (Fig. 5A, B) this finding suggests that the reduction in astrocyte p75NTR with siRNA critically reduced the buffering capacity of astrocytes to isoflurane-induced elevations in proBDNF. No differences in the total numbers of neurons were observed between treatment groups (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Targeting astrocytes in neuronal-astrocyte co-culture for knockdown of p75NTR. (A) Fluorescence immunohistochemical staining of primary astrocyte cultures demonstrates easily identifiable levels of cellular expression of p75NTR (green) that is quantified and normalized to total cell number with DAPI (blue). Relative to transfection with mismatch-control sequence (MM-CON), transfection with small interfering RNA (siRNA) to p75NTR results in significant reduction in both p75NTR immunofluorescence (B) and mRNA expression (C) in astrocytes. (D) Co-cultures stained for p75NTR and co-labeled with the nuclear stain DAPI show both neuronal and astrocyte staining. (E) Relative to transfection with MM-CON, transfection of co-cultures with p75NTR siRNA results in a significant reduction in expression levels of p75NTR, but to a lower degree than that observed in astrocyte cultures (B), consistent with astrocyte-targeted p75NTR knockdown. Graphs are representative of data from three independent experiments each with n = 8 cultures per treatment; mean ± SD, * = P < 0.05 versus control. p75NTR = p75 neurotrophin receptor; DAPI = 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Figure 5.

Isoflurane exposure in neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures following astrocyte-targeted knockdown of p75NTR. (A, B) Co-cultures transfected with small interfering RNA (siRNA) against the proBDNF receptor p75NTR demonstrate low control (CON) levels of dead neurons, identified as both PI-positive (red) and NeuN-positive (green); DAPI (blue) stains all cell nuclei. Isoflurane exposure significantly increased neuronal cell death in siRNA-transfected co-cultures, relative to control gas exposure alone, but failed to increase neuronal death in cultures transfected with mismatch-control (MM-CON) (C, D). Graphs represent three independent experiments with n = 6 cultures per experiment. (E) Levels of proBDNF in media measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay increased in co-cultures treated with either p75NTR siRNA or isoflurane exposure alone. Co-application of p75NTR siRNA and isoflurane resulted in a significantly greater elevation in proBDNF than either treatment alone following isoflurane exposure. Graph is representative of three independent experiments with n = 12 cultures per treatment, each culture measured in duplicate; mean ± SD, * = P < 0.05 versus no treatment; # = P < 0.05 versus all other conditions. p75NTR = p75 neurotrophin receptor; PI = propidium iodide; NeuN = neuronal nuclei; DAPI = 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; proBDNF = pro brain-derived neurotrophic factor; ISO = 1 hr 2% isoflurane treatment.

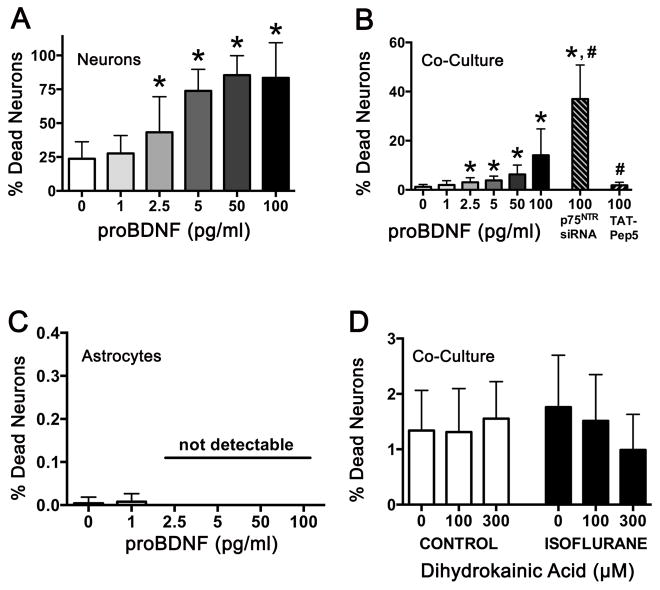

Isoflurane neurotoxicity in neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures is mediated by proBDNF/p75NTR

Application of increasing levels of proBDNF (co-administered with protease inhibitor to prevent conversion to mature BDNF), beginning with physiologic levels measured in media, resulted in a progressive increase in neuronal cell death in both primary neuronal (Fig. 6A) and neuronal-astrocyte co-culture (Fig. 6B). In co-cultures, pre-treatment with p75NTR siRNA augmented neuronal cell death from 100pg/ml proBDNF while pre-treatment with the intracellular p75NTR inhibitor TAT-Pep5 blocked the neurotoxic effect from the same proBDNF dose (Fig. 6B). Thus, similar to observations in neuronal cultures,2, 3 proBDNF-induced cell death of neurons in co-culture is mediated by p75NTR signaling, and mitigated by p75NTR expression on astrocytes. Interestingly, addition of the same concentrations of proBDNF to primary astrocyte cultures did not induce cell death (Fig. 6C), providing evidence for a functional difference between astrocytes and neurons in response to binding of proBDNF to p75NTR. Because glutamatergic excitotoxicity has been proposed as a potential mechanism contributing to anesthetic neurotoxicity26 we investigated whether astrocyte-mediated protection from isoflurane neurotoxicity was mediated by astrocytic glutamate uptake. Addition of the astrocyte glutamate transporter inhibitor dihydrokainic acid did not result in any effect on isoflurane-mediated cell death (Fig. 6D), suggesting that glutamate buffering does not contribute to astrocyte-mediated protection from isoflurane neurotoxicity in these co-cultures. No differences in the total numbers of neurons or astrocytes were observed between treatment groups (data not shown).

Figure 6.

proBDNF/p75NTR signaling mediates neuronal cell death in neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures. (A) Application of increasing doses of recombinant proBDNF plus protease inhibitor induces neuronal cell death in primary neuronal cultures. (B) In neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures application of proBDNF also results in neuronal cell death, but much higher doses are required relative to neuronal cultures. Co-application of p75NTR siRNA exacerbated neuronal cell death while p75NTR intracellular signaling inhibitor Tat-Pep5 reversed this effect, indicating that proBDNF binding to p75NTR on astrocytes and pro-BDNF signaling are involved. (C) In astrocyte cultures application of proBDNF had no effect on cell survival. (D) In neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures, pre-treatment with the astrocyte glutamate transporter inhibitor dihydrokainate had no effect on neuronal cell death subsequent to a 1 hr exposure to 2% isoflurane suggesting glutamate uptake does not contribute to protection. All graphs represent n = 6 cultures per treatment, three fields averaged per culture, mean ± SD. * = P < 0.05 versus no added proBDNF, # = P < 0.05 versus 100 pg/ml proBDNF alone. proBDNF = pro brain-derived neurotrophic factor; p75NTR = p75 neurotrophin receptor; TAT-pep5 = trans-activating transcriptional activator peptide 5; siRNA = small interfering RNA.

Discussion

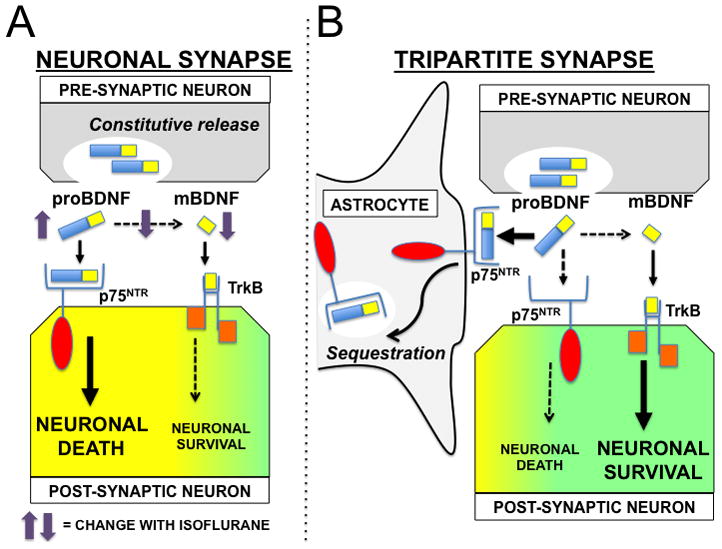

This study is the first to demonstrate that astrocytes protect neurons from isoflurane toxicity, and that this protection occurs via reduced availability of proBDNF to bind to neuronal p75NTR (Fig. 7). Previous findings2 suggested that isoflurane neurotoxicity in primary neuronal cultures is limited to the period of active synaptogenesis (DIV 4–7), and decreases after ~DIV 10. Relatively few studies have investigated the role astrocytes play in the development of brain injury from isoflurane exposure. Lunardi et al.27 demonstrated that prolonged (24 hr) exposure to high dose (3%) isoflurane impaired growth of DIV 4 but not DIV 15 astrocytes. Culley et al.28 observed that isoflurane exposure to astrocytes at DIV 16 did not affect astrocyte survival, or the ability to support synaptogenesis. Most recently, Ryu et al.29 demonstrated that isoflurane pre-exposure of astrocytes at DIV 10 impaired axonal growth in developing co-cultures but did not contribute to astrocyte cell death. In the present study DIV 7 neurons were protected from isoflurane exposure whether in the presence of age-matched (DIV 7) or DIV 21 astrocytes. These observations demonstrate that astrocyte mediated protection is present in relatively immature astrocytes and is maintained in more mature astrocytes.

Figure 7.

A model of astrocyte-mediated protection from isoflurane neurotoxicity. (A) In the neuronal synapse, pro brain-derived neurotrophic factor (proBDNF) is released constitutively from the pre-synaptic neuron and undergoes proteolytic cleavage by plasmin to the mature form (mBDNF). Binding of proBDNF to neuronal post-synaptic p75 neurotrophin receptors (p75NTR) initiates actin destabilization and neuronal cell death, while binding of mBDNF to tyrosine-related kinase B (TrK-B) receptors promotes cytoskeletal stabilization and neuronal cell survival. Isoflurane exposure decreases plasmin activity, leading to an increase in synaptic proBDNF and a decrease in mBDNF, resulting in post-synaptic neuronal cell death. (B) The tripartite synapse includes the contribution of astrocytes to synaptic homeostasis. p75NTR expressed on astrocytes serves to sequester proBDNF from the synaptic cleft. This function effectively buffers the isoflurane-induced increase in neuronal proBDNF/p75NTR binding, thereby promoting post-synaptic neuronal survival.

Significantly more baseline neuronal injury was observed in neurons cultured alone than in neurons cultured with age-matched astrocytes, and the least injury was seen in neurons cultured on mature astrocytes. Neither conditioned media from astrocyte cultures nor conditioned media from co-cultures provided protection from isoflurane neurotoxicity. This suggests that: 1) concentrations of additional secreted factors resulting from neuron-astrocyte cross-talk were either too low or otherwise did not contribute to the neuroprotective effect observed in this study; and 2) the physical presence of astrocytes is necessary for neuroprotection from isoflurane toxicity.

Astrocyte-mediated neuroprotection that requires astrocytes in close proximity is shown in the current model (Fig. 7) of synaptic BDNF-signaling. proBDNF is released from the presynaptic terminal into the synapse, and likely has a limited period of activity prior to conversion to mature BDNF by plasmin. Debate exists as to the physiologic relevance of proBDNF to in vivo signaling.30 Bergami et al.19 previously demonstrated that binding of proBDNF to p75NTR results in endocytosis and removal of proBDNF from the synaptic cleft. Here we observed a significant increase in proBDNF levels in media from co-cultures with astrocyte-targeted knockdown of p75NTR following isoflurane exposure. This suggests that extrasynaptic levels of proBDNF increased secondary to reduced uptake mediated by astrocyte p75NTR.

Ryu et al. recently reported reduced levels of mature BDNF in media from co-cultures of neurons with astrocytes subjected to isoflurane pre-exposure, suggesting an alteration in BDNF signaling, however whether this was due to alterations in proBDNF levels or to changes in plasmin activity was not determined. In the present study, application of increasing levels of recombinant proBDNF resulted in a significant corresponding increase in neuronal cell death in both neuronal cultures and neuronal-astrocyte co-cultures. Interestingly, the lowest toxic dose (2.5 pg/ml) in both culture models approximated the increase in proBDNF levels we observed in media from co-cultures subjected to astrocyte-targeted p75NTR knockdown plus isoflurane exposure, a treatment which increased neuronal cell death.

At a dose of 100 pg/ml proBDNFneuronal cell death in co-cultures increased substantially, likely representing saturation of astrocyte proBNDF uptake. This was exacerbated by p75NTR knockdown, and reversed by inhibition of p75NTR signaling, verifying a proBDNF/p75NTR mechanism of neuronal cell death, possibly via rat sarcoma virus homolog family member A (RhoA)-mediated induction of pro-apoptotic pathways.3 Notably, proBDNF did not kill astrocytes indicating that proBDNF binding to p75NTR has different effects on cell survival between astrocytes and neurons under these conditions. This is supported by previous observations27 that while prolonged exposure of immature astrocytes to high concentrations of isoflurane impaired astrocyte maturation and morphological development, it paradoxically reduced activation of rat sarcoma virus homolog family member A. Moreover, activation of p75NTR by the lower affinity ligand nerve growth factor failed to induce cell death of cultured hippocampal astrocytes.31 Future investigations delineating p75NTR cell signaling pathways in astrocytes may yield further insight into their potential to coordinate synaptic transmission.

Astrocytes regulate synaptogenesis, synaptic function and elimination of synapses through modulation of glutamatergic signaling and via contact-dependent signals.15, 16 Astrocytes have been shown to protect neurons from glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity during pathophysiologic stresses such as stroke,32 traumatic brain injury,33 and spinal cord injury.34 The results from the present study demonstrate that astrocyte glutamate uptake did not contribute to astrocyte-mediated protection from isoflurane, instead suggesting that modulation of post-synaptic proBDNF/p75NTR signaling was responsible for astrocyte-mediated neuroprotection. Functional modulation of BDNF signaling by astrocytes may be relevant in the adult hippocampus where BDNF signaling is central to normal learning and memory formation.8, 9 The results from the present study suggest that astrocytes may provide a novel cellular mechanism to manipulate neuronal BDNF signaling.

While BDNF is a known regulator of neonatal brain development coordinating pro-death and pro-survival signaling, several lines of evidence also support a role for BDNF signaling in recovery from injury in the adult brain following stroke,35 traumatic brain injury,36 and spinal cord injury.37 However, therapies targeting manipulation of BDNF signaling are limited by the short plasma half-life of BDNF38 and relatively poor blood–brain barrier penetrance.39 Future studies utilizing in vivo models of central nervous system injury in adult animals are needed to investigate effects of targeted overexpression of astrocyte p75NTR and inhibition of neuronal p75NTR as potential targets for the development of new therapies to encourage recovery.

Limitations

Caution should be exercised in extrapolating these in vitro results to the clinical setting. For example, despite evidence from the present study demonstrating protection of DIV 7 neurons from isoflurane toxicity by DIV 7 astrocytes, previous studies1 have demonstrated isoflurane-induced neuronal cell death in vivo at post-natal day 7 (PND 7). DIV 7 cultured brain cells are unlikely to fully recapitulate the phenotypes of cells developing in vivo, and in particular, the ratio of astrocytes to neurons in culture is likely higher than seen in vivo at this age and may contribute to the difference between these observations.

Differences between in vivo and in vitro observations may also result from loss of the anatomic organization of the intact brain, and loss of physiologic contributions from other cell types that are absent in culture. Effects of isoflurane on brain perfusion may contribute to in vivo effects, and are also absent in culture. While microglia are present throughout the brain, in our isolated cell cultures they are present at low levels (on average < 2%), suggesting that in these in vitro observations they are unlikely to contribute measurably to the protection seen, even though they may express p75NTR.

Finally, it is interesting to note that astrocytes in the human brain are larger, more complex, and greater in number relative to neurons than in the rodent brain.40 This suggests that human brains may inherently posses a greater capacity for neuroprotection from anesthetic toxicity versus rodent brains, and that bolstering astrocyte defense may be a potential therapeutic strategy.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Supported by National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA) T32 GM089626 and American Heart Association (Dallas, TX, USA) 14FTF-19970029 to Dr. Stary and by National Institutes of Health R01 NS084396 to Dr. Giffard.

Stephen Milburn, BA (Stanford Univ., Dept. of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA) for his assistance with manuscript preparation and Bryce Small, BS (Stanford Univ., Dept. of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine) for his contribution to Figure 7.

Footnotes

Conflict(s) of interest in previous 36 months: none

References

- 1.Jevtovic-Todorovic V. Anesthesia and the developing brain: are we getting closer to understanding the truth? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2011;24:395–9. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3283487247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Head BP, Patel HH, Niesman IR, Drummond JC, Roth DM, Patel PM. Inhibition of p75 neurotrophin receptor attenuates isoflurane-mediated neuronal apoptosis in the neonatal central nervous system. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:813–25. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819b602b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemkuil BP, Head BP, Pearn ML, Patel HH, Drummond JC, Patel PM. Isoflurane neurotoxicity is mediated by p75NTR-RhoA activation and actin depolymerization. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:49–57. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318201dcb3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pencea V, Bingaman KD, Wiegand SJ, Luskin MB. Infusion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor into the lateral ventricle of the adult rat leads to new neurons in the parenchyma of the striatum, septum, thalamus, and hypothalamus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6706–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06706.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vicario-Abejon C, Collin C, McKay RD, Segal M. Neurotrophins induce formation of functional excitatory and inhibitory synapses between cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7256–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07256.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henneberger C, Juttner R, Rothe T, Grantyn R. Postsynaptic action of BDNF on GABAergic synaptic transmission in the superficial layers of the mouse superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:595–603. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.2.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Neurotrophins: roles in neuronal development and function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:677–736. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bekinschtein P, Cammarota M, Katche C, Slipczuk L, Rossato JI, Goldin A, Izquierdo I, Medina JH. BDNF is essential to promote persistence of long-term memory storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2711–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711863105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamada K, Nabeshima T. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor/TrkB signaling in memory processes. J Pharmacol Sci. 2003;91:267–70. doi: 10.1254/jphs.91.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harvey AR, Lovett SJ, Majda BT, Yoon JH, Wheeler LP, Hodgetts SI. Neurotrophic factors for spinal cord repair: Which, where, how and when to apply, and for what period of time? Brain Res. 2014:TBD. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan GB, Vasterling JJ, Vedak PC. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress disorder, and their comorbid conditions: role in pathogenesis and treatment. Behav Pharmacol. 2010;21:427–37. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833d8bc9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benarroch EE. Neuron-astrocyte interactions: partnership for normal function and disease in the central nervous system. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1326–38. doi: 10.4065/80.10.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Araque A, Sanzgiri RP, Parpura V, Haydon PG. Astrocyte-induced modulation of synaptic transmission. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1999;77:699–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schousboe A, Westergaard N, Sonnewald U, Petersen SB, Yu AC, Hertz L. Regulatory role of astrocytes for neuronal biosynthesis and homeostasis of glutamate and GABA. Prog Brain Res. 1992;94:199–211. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61751-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eroglu C, Barres BA. Regulation of synaptic connectivity by glia. Nature. 2010;468:223–31. doi: 10.1038/nature09612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke LE, Barres BA. Emerging roles of astrocytes in neural circuit development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:311–21. doi: 10.1038/nrn3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bushong EA, Martone ME, Jones YZ, Ellisman MH. Protoplasmic astrocytes in CA1 stratum radiatum occupy separate anatomical domains. J Neurosci. 2002;22:183–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00183.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rouach N, Glowinski J, Giaume C. Activity-dependent neuronal control of gap-junctional communication in astrocytes. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1513–26. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergami M, Santi S, Formaggio E, Cagnoli C, Verderio C, Blum R, Berninger B, Matteoli M, Canossa M. Uptake and recycling of pro-BDNF for transmitter-induced secretion by cortical astrocytes. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:213–21. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dugan LL, Bruno VM, Amagasu SM, Giffard RG. Glia modulate the response of murine cortical neurons to excitotoxicity: glia exacerbate AMPA neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4545–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04545.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu L, Lee JE, Giffard RG. Overexpression of bcl-2, bcl-XL or hsp70 in murine cortical astrocytes reduces injury of co-cultured neurons. Neurosci Lett. 1999;277:193–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00882-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voloboueva LA, Duan M, Ouyang Y, Emery JF, Stoy C, Giffard RG. Overexpression of mitochondrial Hsp70/Hsp75 protects astrocytes against ischemic injury in vitro. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1009–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buisson A, Nicole O, Docagne F, Sartelet H, Mackenzie ET, Vivien D. Up-regulation of a serine protease inhibitor in astrocytes mediates the neuroprotective activity of transforming growth factor beta1. FASEB J. 1998;12:1683–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouyang YB, Lu Y, Yue S, Xu LJ, Xiong XX, White RE, Sun X, Giffard RG. miR-181 regulates GRP78 and influences outcome from cerebral ischemia in vitro and in vivo. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45:555–63. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao YL, Xiang Q, Shi QY, Li SY, Tan L, Wang JT, Jin XG, Luo AL. GABAergic excitotoxicity injury of the immature hippocampal pyramidal neurons’ exposure to isoflurane. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:1152–60. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318230b3fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lunardi N, Hucklenbruch C, Latham JR, Scarpa J, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. Isoflurane impairs immature astroglia development in vitro: the role of actin cytoskeleton. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;70:281–91. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31821284e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Culley DJ, Cotran EK, Karlsson E, Palanisamy A, Boyd JD, Xie Z, Crosby G. Isoflurane affects the cytoskeleton but not survival, proliferation, or synaptogenic properties of rat astrocytes in vitro. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110 (Suppl 1):i19–28. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryu YK, Khan S, Smith SC, Mintz CD. Isoflurane impairs the capacity of astrocytes to support neuronal development in a mouse dissociated coculture model. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2014;26:363–8. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barker PA. Whither proBDNF? Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:105–6. doi: 10.1038/nn0209-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cragnolini AB, Huang Y, Gokina P, Friedman WJ. Nerve growth factor attenuates proliferation of astrocytes via the p75 neurotrophin receptor. Glia. 2009;57:1386–92. doi: 10.1002/glia.20857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takano T, Oberheim N, Cotrina ML, Nedergaard M. Astrocytes and ischemic injury. Stroke. 2009;40:S8–12. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.533166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shields J, Kimbler DE, Radwan W, Yanasak N, Sukumari-Ramesh S, Dhandapani KM. Therapeutic targeting of astrocytes after traumatic brain injury. Transl Stroke Res. 2011;2:633–42. doi: 10.1007/s12975-011-0129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falnikar A, Li K, Lepore AC. Therapeutically targeting astrocytes with stem and progenitor cell transplantation following traumatic spinal cord injury. Brain Res. 2014:TBD. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han J, Pollak J, Yang T, Siddiqui MR, Doyle KP, Taravosh-Lahn K, Cekanaviciute E, Han A, Goodman JZ, Jones B, Jing D, Massa SM, Longo FM, Buckwalter MS. Delayed administration of a small molecule tropomyosin-related kinase B ligand promotes recovery after hypoxic-ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:1918–24. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.641878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao X, Chen J. Conditional knockout of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the hippocampus increases death of adult-born immature neurons following traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1325–35. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamy JC, Boakye M. BDNF Val66Met polymorphism alters spinal DC stimulation-induced plasticity in humans. J Neurophysiol. 2013;110:109–16. doi: 10.1152/jn.00116.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morse JK, Wiegand SJ, Anderson K, You Y, Cai N, Carnahan J, Miller J, DiStefano PS, Altar CA, Lindsay RM. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) prevents the degeneration of medial septal cholinergic neurons following fimbria transection. J Neurosci. 1993;13:4146–56. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-10-04146.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poduslo JF, Curran GL. Permeability at the blood-brain and blood-nerve barriers of the neurotrophic factors: NGF, CNTF, NT-3, BDNF. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1996;36:280–6. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00250-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oberheim NA, Takano T, Han X, He W, Lin JH, Wang F, Xu Q, Wyatt JD, Pilcher W, Ojemann JG, Ransom BR, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. Uniquely hominid features of adult human astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3276–87. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4707-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]