Abstract

Objective

To estimate the cost-effectiveness of noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma (NCGA) screening strategies based on new biomarker and endoscopic technologies.

Design

Using an intestinal-type NCGA microsimulation model, we evaluated the following one-time screening strategies for US men: 1) serum pepsinogen to detect gastric atrophy (with endoscopic follow-up of positive screen results), 2) endoscopic screening to detect dysplasia and asymptomatic cancer (with endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) treatment for detected lesions), and 3) Helicobacter pylori screening and treatment. Screening performance, treatment effectiveness, cancer and cost data were based on published literature and databases. Subgroups included current, former and never smokers. Outcomes included lifetime cancer risk and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), expressed as cost per quality-adjusted-life-year (QALY) gained.

Results

Screening the general population at age 50 reduced the lifetime intestinal-type NCGA risk (0.24%) by 26.4% with serum pepsinogen screening, 21.2% with endoscopy and EMR, and 0.2% with H. pylori screening/treatment. Targeting current smokers reduced the lifetime risk (0.35%) by 30.8%, 25.5%, and 0.1%, respectively. For all subgroups, serum pepsinogen screening was more effective and more cost-effective than all other strategies, although its ICER varied from $76,000/QALY (current smokers) to $105,400/QALY (general population). Results were sensitive to H. pylori prevalence, screen age, and serum pepsinogen test sensitivity. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis found that at a $100,000/QALY willingness-to-pay threshold, the probability that serum pepsinogen screening was preferred was 0.97 for current smokers.

Conclusion

Although not warranted for the general population, targeting high-risk smokers for serum pepsinogen screening may be a cost-effective strategy to reduce intestinal-type NCGA mortality.

Keywords: Gastric Cancer, Secondary Prevention, Biomarkers, Helicobacter pylori, Cost-Effectiveness, Decision Analysis

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the third leading-cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide.[1] Despite declines in recent decades, 22,000 individuals in the US are diagnosed each year, less than 30% of these individuals survive more than 5 years, and noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma (NCGA) remains the predominant phenotype.[2] Screening efforts have primarily focused on detecting gastric cancer at earlier stages with more favorable prognosis in countries with high gastric cancer incidence.[3–5] Recent advances in biomarker and endoscopic technologies to detect and treat precancerous and cancerous lesions may offer alternative strategies for NCGA control.

In contrast to other histological subtypes, epidemiological studies have well-established the precancerous development process for intestinal-type NCGA and the role of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and smoking. Normal gastric mucosa progresses to invasive cancer through a series of precancerous lesions.[6] By initiating the precancerous process, H. pylori increases disease risk by as much as 6-fold[7] and is estimated to be responsible for approximately 75% of noncardia cancers.[8] Elevating the risk of progression of existing precancerous lesions to more advanced lesions, smoking increases NCGA risk by approximately 2-fold.[9–12] Other risk factors include diet and genetic factors.

As serum levels for pepsinogen I and II reflect the functional and morphologic status of the gastric mucosa, biomarker-based serum pepsinogen screening may identify individuals at higher risk for gastric cancer.[13, 14] A stepwise screening strategy, starting with a serum pepsinogen test followed by endoscopic biopsy sampling for positive test results, can help to distinguish low-risk individuals from high-risk individuals who are more likely to benefit from subsequent surveillance.[15] The generalized use of the test has been limited despite clinical studies on its potential usefulness.[16–18] Gastric cancer control efforts may be further enhanced by advances in endoscopic technology, including endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), to detect and remove dysplastic/precancerous or cancerous lesions without surgery, which may potentially reduce intestinal-type NCGA risk by 90% among individuals with dysplasia.[19] Findings from a randomized clinical trial suggest that H. pylori treatment may only reduce cancer incidence among individuals without existing precancerous lesions (defined as atrophy, intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia) at time of treatment.[20] The estimated benefits associated with population-based H. pylori screening in the US are therefore likely much lower than previously estimated.[21]

Screening for precursors of NCGA may be an effective strategy for preventing invasive cancer, yet long-term benefits associated with new biomarker and endoscopic technologies are uncertain. Model-based analyses provide a framework for estimating potential benefits and risks associated with screening, extrapolating existing randomized clinical trial results, and guiding the design of future clinical studies by highlighting areas where better data are needed. We therefore employed a decision-analytic simulation-based modeling approach to synthesize the best available epidemiologic, clinical and economic data to assess the potential clinical benefits and cost-effectiveness of alternative screening strategies to reduce intestinal-type NCGA incidence and mortality.

METHODS

Using a mathematical simulation model of intestinal-type NCGA natural history among US men, we estimated the benefits, costs and cost-effectiveness associated with the following screening-based cancer control strategies: 1) serum pepsinogen screening, 2) endoscopic-based screening, and 3) H. pylori screening. Described in detail elsewhere,[22] the model is based on natural history parameters derived via empirical model calibration to age-specific precancerous lesions prevalence[23] and Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer incidence[24] to ensure model outputs are consistent with US epidemiologic data (see Supplemental Materials). For each strategy, we estimated screening test performance, complication rates and treatment effectiveness from the published literature. Costs were based on US Medicare reimbursement rates and SEER-Medicare linked database estimates. Model outcomes included lifetime risk of intestinal-type NCGA, life expectancy, quality-adjusted life expectancy, lifetime costs, and number of cause-specific deaths. To evaluate the relative performance of each strategy, we calculated incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), defined as the additional cost of a specific strategy divided by its additional clinical benefit, compared with the next least expensive strategy, and expressed as cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained. We adopted a societal perspective and discounted all costs and clinical consequences at 3% annually.[25] All costs are reported in 2012 dollars. To identify subgroups for targeted screening, we conducted subgroup analyses based on smoking status at time of screening: never, current and former smokers.

While there is no consensus on the threshold for good value for resources, we present our cost-effectiveness results in the context of the commonly cited threshold of $100,000 per QALY.[26, 27]

Natural history simulation model

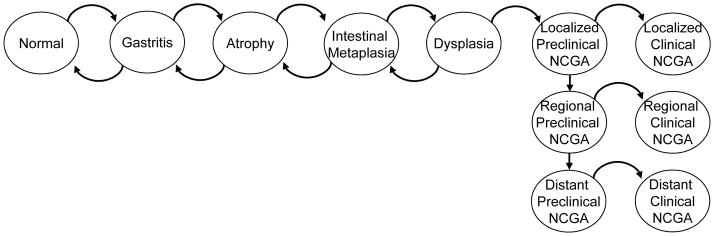

As depicted in Figure 1, the model simulates the development of intestinal-type NCGA through a series of precancerous lesions, which may progress to dysplasia and eventually invasive cancer. At the start of the simulation, 20-year old individuals enter the model and are assigned a risk factor profile for H. pylori and smoking status. Based on epidemiologic data [28], we assumed that precancerous lesions were already present in a subset of 20-years olds, with a greater proportion among those infected with H. pylori. Based on monthly probabilities derived via model calibration (Supplemental Table 1),[29] individuals transition among the health states and are followed throughout their lifetime.

Figure 1. Diagram of intestinal-type NCGA natural history model.

Intestinal-type NCGA develops through a series of precancerous health states as depicted. Each month, individuals face a risk of progression among the health states. Before invasive cancer develops, individuals can also regress to less advanced precancerous lesions. Individuals with preclinical (asymptomatic) cancer can remain asymptomatic or progress to symptomatic clinical cancer. Once individuals develop symptomatic cancer, they are assumed to receive treatment and do not progress to more advanced cancer states. All probabilities are constant, except for the age-specific transition from dysplasia to preclinical cancer. The model was programmed in the computer language C++. NCGA = noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma.

We based H. pylori prevalence and smoking profiles for a 1961–65 birth cohort (corresponding to 50-year old men between calendar years 2011 and 2015) on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and National Health Interview Survey data.[30–33] Specifically, we estimated that 31% of the birth cohort was infected with H. pylori and assumed the following: H. pylori infection is established by age 20,[34] causes gastritis and increases the risk of atrophy,[35] and remains unchanged throughout one’s lifetime.[36, 37] We assumed that an individual’s smoking status may change over their lifetime and estimated that 23% of individuals at age 50 were current smokers (a decline from a peak prevalence of nearly 40% at age 30).[32, 33] We assumed that smoking increases the risk of progression to intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia,[11, 12] and that the magnitude rises with smoking intensity (defined as <10, 10–19, ≥20 cigarettes per day). Upon quitting, individuals face former smoker-specific disease progression rates.[38]

For individuals who developed intestinal-type NCGA, stage-specific mortality rates were based on SEER estimates.[24] Competing cause mortality was based on US birth cohort-specific life tables [39, 40] and adjusted for smoking intensity using published relative risk estimates.[41]

To assess the face validity and projective validity of the model, we compared model outputs to data not used for model parameterization or calibration. Model estimates of the relative risk of intestinal-type NGCA associated with H. pylori infection (3.6) and smoking (1.6) were consistent with published estimates (95% CI, 2.7 to 7.2 and 1.5 to 1.8, respectively).[7, 42] The proportion of all cancers occurring in H. pylori-positive individuals (60%) fell within the calculated population attributable fraction range for the cohort (38–65%).[43] Modeled estimates for prevalence of precancerous lesions and 10-year cancer risk for individuals with dysplasia also approximated published estimates (see Supplemental Materials for full details).[15, 44]

Strategies

Compared to no screening, we evaluated the following one-time screening strategies at age 50: 1) serum pepsinogen screening, 2) endoscopic screening, and 3) H. pylori screening.

For serum pepsinogen screening, all individuals with a positive assay test result for atrophy (defined as serum pepsinogen I levels ≤70 μg/l together with pepsinogen I/II ratio ≤3.0) were followed up by endoscopy with 7 to 9 random biopsies of the gastric mucosa.[45] All individuals with a positive endoscopy for dysplasia or asymptomatic localized cancer (detected either macroscopically via endoscopy or histologically based on gastric biopsies) underwent EMR treatment to remove lesions; those with a negative endoscopic result returned for a follow-up endoscopy in 10 years. Individuals with an initial negative serum pepsinogen test result received no further treatment or follow-up. As part of standard practice, we assumed that individuals would also be tested for H. pylori and all individuals who tested positive for the infection would receive standard triple therapy (20 mg omeprazole, 1 g amoxicillin, 500 mg clarithromycin, twice daily).

For endoscopic screening, individuals with a positive screen result (based on biopsy sampling) for dysplasia or asymptomatic localized cancer received EMR treatment; those with a negative biopsy result received no additional follow-up care.

For both the serum pepsinogen and endoscopic screening strategies, we assumed: 1) only asymptomatic localized cancers detected via endoscopy benefited from screening (i.e., negligible survival benefit for detected regional and distant cancers), 2) all dysplastic lesions (detected macroscopically and/or histologically) and submucosal localized cancers (American Joint Committee on Cancer (sixth edition) stage IA) were eligible for EMR treatment; all other localized tumors were surgically treated, and 3) all individuals treated with EMR returned for post-treatment surveillance via endoscopy for recurrence in 10 years.

For H. pylori screening, all individuals with a positive test result received standard 10-day triple therapy (described above).

We evaluated the screening strategies for the overall cohort and smoking subgroups based on smoking status at time of screening (never, current, or former smokers).

Clinical data

For each strategy, we estimated screening test characteristics, complication rates and treatment effectiveness based on data from published clinical studies (Table 1).[18, 20, 24, 46–64] For the serum pepsinogen test, sensitivity and specificity were based on the ability to detect atrophy (with and without more advanced precancerous lesions), with dysplasia and asymptomatic cancerous lesions identified via subsequent endoscopy and random biopsy sampling. All endoscopic procedures, including EMR, were associated with a risk of severe bleeding or perforation requiring surgery.[51, 53] After EMR treatment, individuals faced a risk of recurrence from incomplete resections and, for cancerous lesions, metachronous lesions (which we assumed stemmed from undetected dysplasia).[52, 53, 57] For H. pylori treatment, we assumed standard triple therapy reduced the risk of progressing from gastritis to atrophy to H. pylori-negative rates [20] with 80% efficacy.[65]

Table 1.

Select model parameters: base case value and plausible range

| Variables | Base case | Range for Sensitivity Analysis | Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis* | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distribution | Range (95%CI) | ||||

| Clinical | |||||

| Screening, % | |||||

| Serum pepsinogen test to detect atrophy† | [18, 46] | ||||

| Sensitivity | 71 | 58–82 | Beta | 59–82 | |

| Specificity | 98 | 97–99 | Beta | 97–99 | |

| H. pylori test | [47, 48] | ||||

| Sensitivity | 85 | 68–99 | Normal | 70–98 | |

| Specificity | 79 | 63–95 | Normal | 63–94 | |

| Endoscopy to detect dysplasia and asymptomatic cancer | [49, 50] | ||||

| Sensitivity | 81 | 78–84 | Beta | 78–84 | |

| Specificity | 100 | 95–100 | Beta | 99–100 | |

| Endoscopic screening complications requiring surgery, proportion | [51] | ||||

| Bleeding | 0.0011 | 0.000–0.003 | Beta | 0.000–0.002 | |

| Perforation | 0.0009 | 0.000–0.002 | Beta | 0.000–0.002 | |

| Endoscopic mucosal resection treatment | |||||

| Proportion eligible | |||||

| Dysplasia | 1.0 | 0.9–1.0 | ‡ | -- | |

| Preclinical local cancer | 0.65 | 0.55–0.70 | ‡ | -- | [24] |

| Proportion with complete resections | |||||

| Dysplasia | 0.87 | 0.81–0.91 | Beta | 0.82–0.91 | [52] |

| Preclinical local cancer | 0.94 | 0.91–0.97 | Beta | 0.92–0.97 | [53] |

| Proportion of incomplete resections requiring surgery | 0.36 | 0.31–0.42 | Beta | 0.31–0.41 | [54, 55] |

| Complications | |||||

| Bleeding | 0.014 | 0.005–0.033 | Beta | 0.003–0.027 | [53] |

| Perforation | 0.003 | 0.000–0.016 | Beta | 0.000–0.009 | [53] |

| Surgical mortality risk§ | 0.005 | 0.0002–0.015 | Beta | 0.004–0.006 | [56] |

| Outcomes | |||||

| H. pylori treatment effectiveness | [20] | ||||

| Progression of gastritis to atrophy, relative risk | 0.2 | 0.0–0.8 | ‡ | --- | [65] |

| EMR treatment effectiveness, proportion | |||||

| Dysplasia | [52] | ||||

| Remnant lesion | 0.026 | 0.008–0.059 | Beta | 0.005–0.048 | |

| Preclinical local cancer | [53, 57] | ||||

| EMR | |||||

| Local recurrence | 0.012 | 0.001–0.041 | Beta | 0.001–0.028 | |

| Metachronous cancer | 0.058 | 0.028–0.104 | Beta | 0.024–0.092 | |

| Surgery | |||||

| Local recurrence | 0.011 | 0.003–0.027 | Beta | 0.002–0.021 | |

| Metachronous cancer | 0.011 | 0.003–0.027 | Beta | 0.002–0.021 | |

| Cancer stage-specific annual mortality rate|| | 0.21–0.98 | --- | --- | [24] | |

| Quality of life | |||||

| Age-related quality weight, utility | 0.782–0.928 | --- | --- | [58] | |

| Utility reduction, duration | |||||

| Endoscopy or EMR | − 1 day | --- | --- | ||

| Gastrectomy | − 2 weeks | --- | --- | ||

| Symptomatic cancer quality weight, utility | 0.49 | 0.17–0.79 | Normal | 0.17–0.78 | [59] |

| Costs | |||||

| Direct, 2012$ | [60, 61] | ||||

| Physician visit (CPT 99213) | 70 | --- | --- | ||

| Serum pepsinogen I, II test (CPT 83519) | 40 | --- | --- | ||

| H. pylori test (CPT 86677) | 20 | --- | --- | ||

| H. pylori triple therapy | 120 | --- | --- | ||

| Endoscopy (CPT 43230, 88305; APC 0141) | 980 | --- | --- | ||

| EMR (CPT 43239, 43244, 43251, 88305; APC 0141) | 1500 | --- | --- | ||

| Endoscopic complication requiring surgery (CPT 43501, 99222, 99232, 99238, 88305; DRG 155) | 8510 | --- | --- | ||

| Surgery | |||||

| Dysplasia (CPT 43610, 99222, 99232, 99238, 88305; DRG 155) | 8150 | --- | --- | ||

| Preclinical local cancer (CPT 43611, 99222, 99232, 99238, 88305; DRG 154) | 23,570 | --- | --- | ||

| Cancer treatment by stage, per year¶ | [62] | ||||

| Initial year | |||||

| Local | 51,410 | Normal | 46,950–55,930 | ||

| Regional | 74,720 | Normal | 69,350–80,070 | ||

| Distant | 69,160 | Normal | 60,480–77,670 | ||

| Final year | |||||

| Local | 59,340 | Normal | 54,970–64,090 | ||

| Regional | 68,320 | Normal | 64,780–72,310 | ||

| Distant | 102,740 | Normal | 97,560–107,940 | ||

| Indirect | |||||

| Median hourly wage, 2012$ | 16.83 | Normal | 9.40–25.10 | [63] | |

| Lost time, hours | |||||

| Screening attendance | 2 | --- | --- | ||

| Endoscopy or EMR | 8 | --- | --- | ||

| Gastrectomy | 80 | --- | --- | ||

| Cancer treatment, per year | [64] | ||||

| Initial year | 350 | --- | --- | ||

| Final year | 520 | --- | --- | ||

CPT = current procedural terminology; APC = ambulatory payment classifications; DRG = diagnosis-related group; EMR = endoscopic mucosal resection.

For probabilistic sensitivity analyses, key model parameters were varied as indicated. We used beta distributions for parameters for which count data were available. For all others, we used normal distributions (bounded by 0 and 1) based on reported 95% confidence intervals. For costs, we assumed that Medicare reimbursement rates were fixed, but varied stage- and phase-specific cancer treatment costs based on published 95% confidence intervals.

Based on the following cutoff values: pepsinogen I levels ≤70μg/l and pepsinogen I/II ratio ≤ 3.0.

Parameter value was based on assumption and was not varied in probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

We assumed individuals were healthy or had mild systemic disease and surgery was emergent with intermediate procedure risk.

Annual mortality rate varies by time since diagnosis. After 10 years, we assumed individuals faced negligible risk of dying from intestinal-type NCGA (and did not incur any additional costs associated with cancer treatment).

Stage-specific (local, regional, distant). Annual cost for continuing phase (years in between first and last year) was $2540. We assumed that preclinical (asymptomatic) regional and distant cancers detected via screening would not experience any gains in survival, but would incur additional costs, approximated by continuing phase costs until they would otherwise become symptomatic.

To reflect quality of life, we used sex- and age-specific population-based weights[58] and disease-specific weights.[59] We also assumed that endoscopic procedures and surgical procedures were associated with a 50% utility reduction for 1 day and 2 weeks, respectively.

Cost data

For each strategy, we estimated direct medical costs based on 2012 Medicare reimbursement rates (Table 1). Costs included physician costs, pathologist costs (for biopsy evaluation), and facilities and/or hospitalization costs associated with endoscopic or surgical procedures.[60] We used phase-specific treatment costs for gastric cancer.[62] Drug costs were based on median Wholesale Acquisition Cost among leading manufacturers.[61] Indirect patient costs were based on time lost from work,[63] including phase-specific time costs for cancer treatment.[64]

Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses on key variables to explore how results varied across plausible ranges established from published studies. To reflect the impact of uncertainty surrounding disease natural history on results, we conducted analyses with a subset of 50 good-fitting natural history parameters identified via model calibration (Supplemental Table 1) and report the range across all parameter sets for all model outcomes. In addition, we conducted a probabilistic sensitivity analysis using 1000 second-order Monte Carlo simulations, in which key model parameters, including natural history parameter sets, were simultaneously varied.

RESULTS

Clinical Benefits

General population

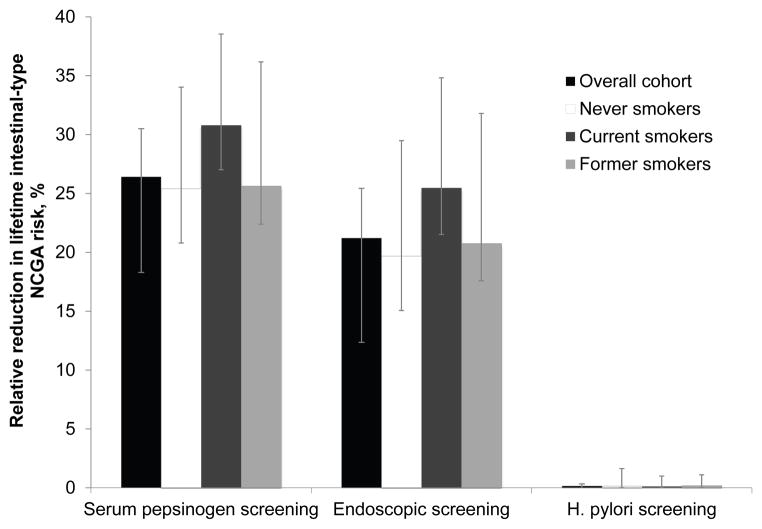

For a hypothetical cohort of 20-year old men, the modeled lifetime risk of intestinal-type NCGA was 0.24% (Table 2). The relative reduction in intestinal-type NCGA lifetime risk was 26.4% with serum pepsinogen screening (range, 22.3% to 34.5%), 21.2% with endoscopic-based screening (range, 17.0% to 30.1%), and 0.2% with H. pylori screening at age 50 (range, 0.0% to 1.2%) (Figure 2). The gain in life expectancy was greatest for serum pepsinogen screening (2.7 days; range, 2.4 to 4.2 days) compared to endoscopy with EMR (2.4 days; range, 2.1 to 3.9 days) and H. pylori screening and treatment (0.01 days; range, 0.00–0.07 days) (Table 2). Among individuals with a positive serum pepsinogen result, the life expectancy gain was 1.2 months, and among those with a positive follow-up endoscopy for dysplasia or asymptomatic cancer, 1.2 years.

Table 2.

Clinical and economic model outcomes associated with NCGA screening strategies for the overall cohort and smoking subgroups (per-person averages)

| Strategy | Lifetime intestinal-type NCGA risk, % | Reduction in lifetime intestinal-type NCGA risk, %* (range†) | Conditional LE, years‡ | Gain in LE, days* (range†) | Total QALYs§ | Incremental QALYs§|| | Total costs, $§ | Incremental costs, $§|| | ICER, $ per QALY¶ | Probability strategy is preferred at a $100K per QALY threshold** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall cohort (base case) | ||||||||||

| No screening | 0.236 | -- | 56.8009 | -- | 23.7820 | -- | 45.2 | -- | -- | 0.53 |

| H. pylori screening | 0.235 | 0.2 (0.0–1.2) | 56.8009 | 0.01 (0.00–0.07) | 23.7820 | 0.0000 | 110.9 | 65.8 | †† | 0.00 |

| Serum pepsinogen screening | 0.174 | 26.4 (22.3–34.5) | 56.8084 | 2.7 (2.4–4.2) | 23.7833 | 0.0013 | 183.7 | 72.7 | 105,400 | 0.47 |

| Endoscopic screening | 0.186 | 21.2 (17.0–30.1) | 56.8074 | 2.4 (2.1–3.9) | 23.7827 | −0.0005 | 476.8 | 293.1 | ‡‡ | |

| Never smokers§§ | ||||||||||

| No screening | 0.181 | -- | 61.6862 | -- | 24.9698 | -- | 32.8 | -- | -- | 0.95 |

| H. pylori screening | 0.180 | 0.2 (0.0–1.6) | 61.6862 | 0.01 (0.00–0.08) | 24.9698 | 0.0000 | 103.6 | 70.8 | †† | 0.00 |

| Serum pepsinogen screening | 0.135 | 25.4 (20.8–34.0) | 61.6924 | 2.3 (1.5–3.9) | 24.9708 | 0.0010 | 174.1 | 70.5 | 137,800 | 0.05 |

| Endoscopic screening | 0.145 | 19.7 (15.1–29.5) | 61.6913 | 1.9 (1.2–3.5) | 24.9702 | −0.0006 | 497.9 | 323.8 | ‡‡ | 0.00 |

| Current smokers§§ | ||||||||||

| No screening | 0.349 | -- | 54.9169 | -- | 23.9483 | -- | 69.0 | -- | -- | 0.03 |

| H. pylori screening | 0.349 | 0.1 (0.0–1.0) | 54.9169 | 0.01 (0.00–0.07) | 23.9483 | 0.0000 | 139.7 | 70.7 | †† | 0.00 |

| Serum pepsinogen screening | 0.241 | 30.8 (27.0–38.5) | 54.9279 | 4.0 (3.6–5.4) | 23.9504 | 0.0021 | 226.5 | 86.8 | 76,000 | 0.97 |

| Endoscopic screening | 0.260 | 25.5 (21.5–34.8) | 54.9269 | 3.6 (3.1–5.3) | 23.9499 | −0.0005 | 532.1 | 305.5 | ‡‡ | 0.00 |

| Former smokers§§ | ||||||||||

| No screening | 0.300 | -- | 60.1750 | -- | 24.7607 | -- | 54.5 | -- | -- | 0.15 |

| H. pylori screening | 0.299 | 0.2 (0.0–1.1) | 60.1750 | 0.02 (0.00–0.08) | 24.7607 | 0.0000 | 125.2 | 70.7 | †† | 0.00 |

| Serum pepsinogen screening | 0.223 | 25.6 (22.4–36.2) | 60.1847 | 3.6 (3.1–7.3) | 24.7624 | 0.0017 | 213.3 | 88.1 | 94,500 | 0.85 |

| Endoscopic screening | 0.238 | 20.8 (17.6–31.8) | 60.1835 | 3.1 (2.8–7.0) | 24.7618 | −0.0006 | 518.9 | 305.6 | ‡‡ | 0.00 |

NCGA = noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma; LE = life expectancy; QALY = quality-adjusted life year; ICER = incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

Compared to no screening strategy.

Range among 50 good-fitting natural history parameter sets.

At age 20, such that overall life expectancy = 20 years + conditional life expectancy.

QALYs and costs discounted at 3% annually.[25]

Compared to previous strategy.

Defined as the additional cost of a specific strategy divided by its additional clinical benefit, compared with the next least expensive strategy.

Based on 1000 second-order Monte Carlo simulations.

Eliminated by extended dominance (i.e. less effective and less cost-effective than a more expensive strategy).

Eliminated by strong dominance (i.e. less effective and more costly than another strategy).

Based on smoking status among individuals alive at time of screening at age 50.

Figure 2. Relative reduction in lifetime intestinal-type NCGA risk among the overall cohort and smoking subgroups.

Serum pepsinogen screening was associated with the greatest relative reduction in lifetime intestinal-type NCGA risk compared to no screening. The reduction associated with H. pylori screening was the smallest (<0.2%). Results were similar for the overall cohort (black bars) and smoking subgroups, including never smokers (white bars), current smokers (dark grey bars) and former smokers (light grey bars). Error bars depict the range among the subset of 50 randomly selected good-fitting natural history parameter sets. A positive serum pepsinogen screen was defined as: pepsinogen I levels ≤70μg/l and pepsinogen I/II ratio ≤ 3.0. H. pylori = Helicobacter pylori.

Among a cohort of 10 million 20-year old men, the model estimated that serum pepsinogen screening would prevent 5,126 (range, 4,687 to 8,316), or 27.0% (range, 23.2 to 34.7%), of the projected 19,014 intestinal-type NCGA deaths (range, 16,576 to 26,255) (Table 3). The estimated number needed to screen to prevent 1 intestinal-type NCGA death was 1,813 (range, 1,117 to 1,982). The estimated number of endoscopies needed was 295 (range, 216 to 378). Table 3 depicts additional results.

Table 3.

Estimated number of intestinal-type NCGA deaths, screening-related deaths and net number of deaths averted associated with NCGA screening strategies for the overall cohort and smoking subgroups

| Strategy | Intestinal-type NCGA deaths*(range†) | Screening-related deaths*(range†) |

Net number of deaths averted|| (range†) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total‡ | Number prevented |

Percent prevented |

Number of screens needed to prevent 1 death§ |

Number of endoscopies to prevent 1 death |

Endoscopic procedures |

Surgical procedures |

||

| Overall cohort (base case) – per 10 million men | ||||||||

| No screening | 19,014 (16,576–26,255) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| H. pylori screening | 18,986 (16,485–26,253) | 28 (0–220) | 0.1% (0.0–1.2%) | 331,859 (42,235–9,292,208) | N/A | 0 | 0 | 28 (0–220) |

| Serum pepsinogen screening | 13,888 (11,881–21,240) | 5,126 (4,687–8,316) | 27.0% (23.2–34.7%) | 1,813 (1,117–1,982) | 295 (216–378) | 21 (18–41) | 12 (7–29) | 5,093 (4,647–8,250) |

| Endoscopic screening | 14,867 (11,183–19,804) | 4,147 (3,822–7,324) | 21.8% (17.6–30.5%) | 2,241 (1,269–2,431) | ¶ | 108 (102–113) | 15 (6–28) | 4,024 (3,709–7,184) |

| Never smokers** | ||||||||

| No screening | 7,371 (4,261–12,039) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| H. pylori screening | 7,362 (4,239–7,362) | 9 (0–128) | 0.1% (0.0–1.6%) | 559,871 (39,365–5,038,922) | N/A | 0 | 0 | 9 (0–128) |

| Serum pepsinogen screening | 5,437 (2,797–9,210) | 1,934 (1,247–3,617) | 26.2% (21.8–34.9%) | 2,605 (1,393–4,041) | 367 (268–566) | 4 (4–19) | 7 (2–14) | 1,923 (1,236–3,586) |

| Endoscopic screening | 5,856 (2,983–9,871) | 1,515 (1,010–3,074) | 20.6% (15.7–30.6%) | 3,326 (1,639–4,989) | ¶ | 48 (47–52) | 6 (2–14) | 1461 (957–3,008) |

| Current smokers** | ||||||||

| No screening | 5,758 (4,836–7,344) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| H. pylori screening | 5,751 (4,802–7,342) | 7 (0–48) | 0.1% (0.0–0.9%) | 299,143 (43,624–2,094,067) | N/A | 0 | 0 | 7 (0–48) |

| Serum pepsinogen screening | 3,948 (3,175–4,917) | 1,810 (1,602–2,476) | 31.4% (27.8–38.5%) | 1,157 (846–1,307) | 218 (174–297) | 7 (5–12) | 3 (1–9) | 1,800 (1,593–2,458) |

| Endoscopic screening | 4,263 (3,477–5,361) | 1,495 (1,282–2,262) | 26.0% (22.3–35.2%) | 1,401 (926–1,633) | ¶ | 29 (27–32) | 6 (2–11) | 1,460 (1,253–2,224) |

| Former smokers** | ||||||||

| No screening | 5,205 (4,301–8,906) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| H. pylori screening | 5,193 (4,257–8,906) | 12 (0–61) | 0.2% (0.0–1.1%) | 179,965 (35,403–2,159,559) | N/A | 0 | 0 | 12 (0–61) |

| Serum pepsinogen screening | 3,823 (3,070–5,851) | 1,382 (1,231–3,055) | 26.6% (23.7–36.7%) | 1,563 (707–1,754) | 295 (160–372) | 10 (5–13) | 2 (2–12) | 1,370 (1,216–3,035) |

| Endoscopic screening | 4,068 (3,276–6,261) | 1,137 (1,025–2,690) | 21.8% (18.3–32.8%) | 1,899 (803–2,107) | ¶ | 31 (27–33) | 3 (1–8) | 1,103 (991–2,654) |

Compared to no screening strategy.

Range among 50 good-fitting natural history parameter sets.

Subgroup estimates do not sum to overall estimates because 680 intestinal-type NCGA deaths (range, 517 to 1022) among the cohort of 10 million 20-year old men occurred before screening at age 50.

For H. pylori screening strategy, range excludes parameter sets that estimated zero deaths prevented with screening. Specifically, 1 parameter set for the overall cohort, 4 for never smokers, 3 for current smokers and 9 for former smokers.

Defined as number of intestinal-type NCGA deaths prevented minus number of screening-related deaths.

Same as the number of screens needed to prevent 1 intestinal-type NCGA death because screening strategy was endoscopy-based.

Based on smoking status among individuals alive at time of screening at age 50. Results shown are per approximately 5.04 million never smokers, 2.10 million current smokers and 2.16 million former smokers. Among the cohort of 10 million 20-year men, an estimated 0.70 million died from background mortality causes before age 50 and were not included in the subgroup analyses.

Current or former smokers

The relative reduction in lifetime intestinal-type NCGA risk was greatest among current smokers (Figure 2). Targeting current smokers at age 50 reduced the lifetime risk (0.35%) by 30.8% with serum pepsinogen screening (range, 27.0 to 38.5%), 25.5% with endoscopy and EMR (range, 21.5 to 34.8%), and 0.1% with H. pylori screening and treatment (range, 0.0 to 1.0%). The number of days gained for each strategy was higher for current smokers (Table 2). Current smokers with a positive serum pepsinogen screen test result also had a greater gain in life expectancy compared to never or former smokers (1.4 months versus 1.1 to 1.2 months, respectively).

Among the approximately 2.10 million individuals who were current smokers at age 50, serum pepsinogen screening would prevent 1,810 (range, 1,602 to 2,476), or 31.4% (range, 27.8 to 38.5%), of the projected 5,758 intestinal-type NCGA deaths (range, 4,836 to 7,344). The percent reduction in number of intestinal-type NCGA deaths prevented was similar for never and former smokers, reflecting the reduced risk of progressing to invasive cancer associated with smoking cessation. The model estimated that approximately 1,157 current smokers (range, 846 to 1,307) would need to be screened to prevent 1 intestinal-type NCGA death. The corresponding number of endoscopies needed was 218 (range, 174 to 297).

Cost-effectiveness analysis

General population

For the overall cohort, compared to no screening, serum pepsinogen screening had an ICER of $105,400 per QALY gained (Table 2). Serum pepsinogen screening dominated the other screening strategies, as it was either less costly and more effective (endoscopic screening) or more effective and more cost-effective (H. pylori screening).

Current or former smokers

ICERs were more attractive for current smokers ($76,000 per QALY gained) and former smokers ($94,500 per QALY gained), and less attractive for never smokers ($137,800) (Table 2).

Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis

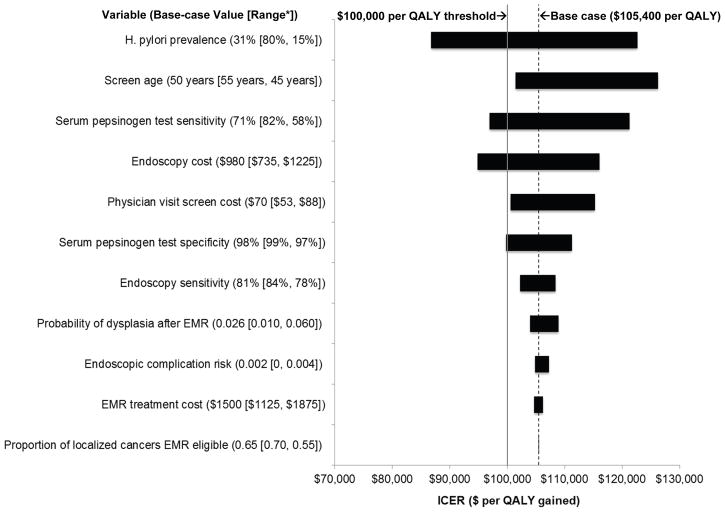

For the overall cohort, results for the serum pepsinogen screening strategy were most sensitive to H. pylori prevalence, screen age, serum pepsinogen test sensitivity, and costs associated with endoscopic follow-up (Figure 3). Results were moderately sensitive to serum pepsinogen screening costs and test specificity. Results remained largely unchanged over the plausible range for endoscopic sensitivity for dysplastic and cancerous lesions, EMR treatment effectiveness and complication risks, and proportion of EMR-eligible localized cancers.

Figure 3. Tornado diagram on one-way sensitivity analysis for serum pepsinogen screening strategy: select model parameters.

Based on one-way sensitivity analyses, this figure depicts the relative influence of select model parameters on results for serum pepsinogen screening for the overall cohort. The x-axis shows the effect of changes in selected variables on the ICER for serum pepsinogen screening at age 50 (compared to no assessment). The y-axis shows selected model parameters, with the base case value and range used in the sensitivity analysis shown in parentheses. The shaded bars indicate the variation in the ICER caused by changes in the value of the indicated variable while all other variables were held constant. The dotted vertical black line indicates the ICER for the base case. The solid vertical grey line represents the commonly used $100,000 per QALY cost-effectiveness threshold. *The first number in the range indicates value yielding the lowest ICER; the second indicates value yielding the highest ICER. H. pylori = Helicobacter pylori; QALY = quality-adjusted life year; ICER = incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; EMR = endoscopic mucosal resection.

We conducted scenario analyses for the overall cohort to explore alternative model assumptions. In our base case, we used estimates for surgical mortality risks among asymptomatic individuals in good health; if age-specific risks for symptomatic patients undergoing surgery were used instead,[66] the ICER for serum pepsinogen screening increased to $128,400 per QALY gained. If 5% of endoscopic procedures required hospitalization (related to complications or incidental findings that required follow-up care), the ICER increased to $120,600 per QALY gained. Similarly, if follow-up endoscopic surveillance was based on only macroscopic findings (i.e. no gastric biopsies were taken), both the reduction in cancer risk (21% vs. 26% in base case) and attractiveness of serum pepsinogen screening ($130,000 vs. $105,400 per QALY gained in base case) declined. If we assumed that after EMR treatment, individuals still harbored intestinal metaplastic lesions (which could progress to invasive cancer), serum pepsinogen screening was also less attractive (ICER = $116,000 per QALY gained). For all these scenarios, ICERs remained less than $93,000 per QALY gained for current smokers.

To assess the impact of H. pylori prevalence, we determined the threshold value needed for serum pepsinogen screening to be considered cost-effective. At a $100,000 per QALY gained threshold, 40% of the cohort would need to be H. pylori infected (base case = 31%) (Supplemental Figure 1). For current smokers, screening was considered cost-effective at nearly all prevalence levels. In contrast, for never smokers, the ICER exceeded the $100,000 per QALY threshold at all prevalence levels.

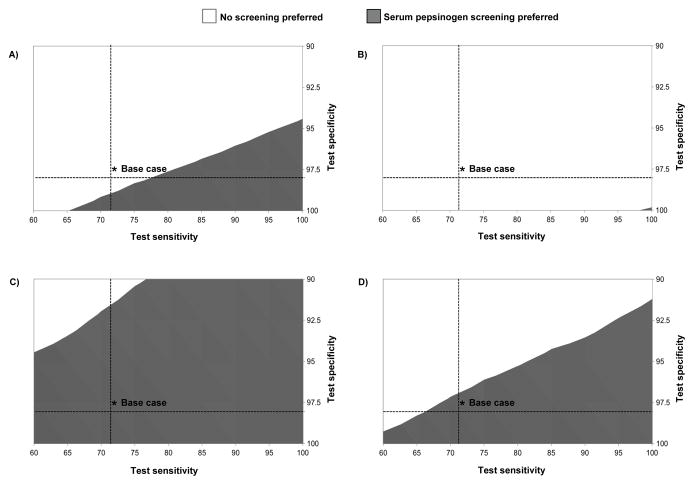

Two-way threshold analysis on serum pepsinogen test characteristics similarly found that the range of possible values for which serum pepsinogen would be preferred was much broader for current smokers compared to the other subgroups (Figure 4). For current smokers, if sensitivity was greater than 60%, serum pepsinogen screening was the preferred strategy as long as test specificity was greater than 94%. For never smokers, serum pepsinogen screening was preferred only if the test had nearly perfect performance.

Figure 4. Two-way threshold analysis on serum pepsinogen test characteristics for the overall cohort and smoking subgroups.

The preferred strategy based on serum pepsinogen screening test sensitivity and specificity are shown for the overall cohort (Panel A) and smoking subgroups (never smokers [Panel B], current smokers [Panel C], and former smokers [Panel D]). In each panel, the shaded grey region indicates the range of values over which serum pepsinogen screening would be considered the preferred strategy at a cost-effectiveness threshold of $100,000 per QALY gained. For example, for never smokers, serum pepsinogen screening would be the preferred strategy only with nearly perfect test sensitivity and specificity. For all possible test characteristic values depicted, serum pepsinogen screening dominated all other screening strategies, in that it was either less costly and more effective (endoscopic screening) or more effective and more cost-effective (H. pylori screening). A positive serum pepsinogen screen was defined as: pepsinogen I levels ≤70μg/l and pepsinogen I/II ratio ≤ 3.0.

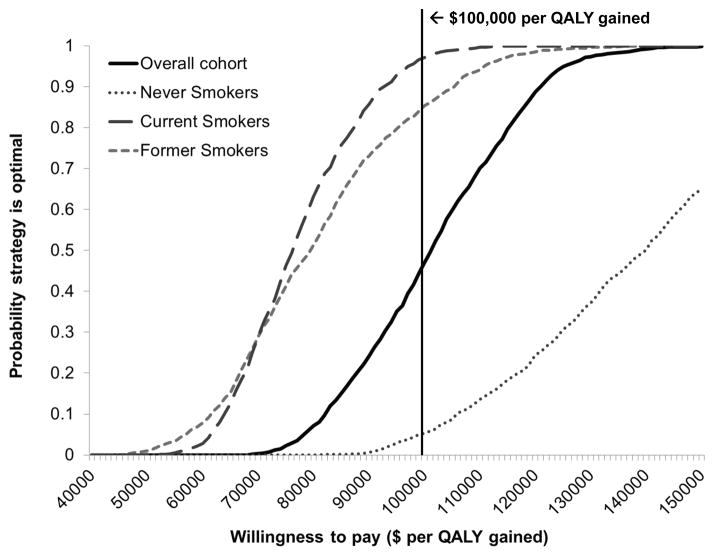

For the overall cohort, probabilistic sensitivity analysis suggested that at a cost-effectiveness threshold of $100,000 per QALY gained, the probability that serum pepsinogen screening was the preferred strategy was 0.47 (Table 2 and Figure 5). The probability was 0.97 for current smokers and 0.85 for former smokers.

Figure 5. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for the overall cohort and smoking subgroups.

To illustrate the uncertainty surrounding ICER estimates, the cost-effectiveness acceptability curves depict the probability that a given strategy is the preferred strategy across a range of cost-effectiveness ratios. Results are depicted for the overall cohort (black solid lines) and subgroups, including never smokers (grey dotted line), current smokers (grey long dashed line), and former smokers (grey short dashed line). Results are based on 1000 second-order Monte Caro simulations in which model variables were simultaneously varied. The solid black vertical line indicates the $100,000 per QALY willingness-to-pay threshold commonly used as a benchmark in the US. QALY = quality-adjusted life year; ICER = incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

DISCUSSION

Although intestinal-type NCGA incidence has declined over the past century, disease risk is largely determined by H. pylori infection acquired in childhood and the number of cases is projected to remain considerable for decades.[29] To provide insight into this important public health and clinical problem and explore options for secondary prevention, we employed a model-based approach to estimate the comparative benefits and cost-effectiveness associated with several screening strategies. Our findings suggest that although a one-time serum pepsinogen screening (with endoscopic follow-up and EMR treatment if needed) at age 50 can prevent as many as 1 in 4 intestinal-type NCGAs among US men, general population-wide screening is unlikely to be a high-value strategy for improving cancer outcomes. However, screening targeted to current smokers who are at elevated risk for premature death[67] may be an effective and cost-effective strategy to reduce NCGA mortality.

Our study is the first simulation model-based analysis to evaluate the clinical benefits and economic consequences of serum pepsinogen screening in the US. Previous model-based studies have focused on high-risk populations in Asia,[68] or estimated the short-term economics of serum pepsinogen testing as a follow-up strategy for individuals diagnosed with atrophy or intestinal metaplasia.[69] Neither study estimated the clinical benefits associated with serum pepsinogen screening in terms of a reduction in cancer risk, or provided estimates for smoking subgroups which can be used as the basis for targeting screening efforts. Consistent with published studies (Supplemental Table 2),[46, 70–75] our model-based estimates of serum pepsinogen screening performance underscore the potential usefulness of the test to detect and distinguish individuals at higher risk for developing cancer from those at lower risk.[76, 77] Furthermore, our estimates of the number needed to screen (NNS) to prevent one intestinal-type NCGA death (1157 US male smokers) suggest that serum pepsinogen screening may have similar benefits to mammography screening among 50–59 year old women (NNS = 1339 to prevent 1 breast cancer death), albeit smaller benefits than low-dose computed tomography (NNS = 320 to prevent 1 lung cancer death)[78–80] or flexible sigmoidoscopy (NNS = 871 to prevent 1 colorectal cancer death).[81] However, our findings should be cautiously considered given the notable uncertainty surrounding serum pepsinogen test performance,[17] limited evidence in low-risk populations,[18] and concerns surrounding the translation of clinical findings in high-risk populations to low-risk populations.[82] As better data become available, our model can be refined and recalibrated to reflect these data, and as such, can serve as an iterative tool to provide updated assessments of the likely health and economic outcomes associated with secondary gastric cancer control efforts.

The serum pepsinogen test has also been proposed as the basis for screening for intestinal-type NCGA itself (in contrast to identifying individuals with atrophy who are at elevated risk for NCGA as in our analysis). Our model found, however, that such a strategy, with a 77% sensitivity and 73% specificity for dysplastic and cancerous lesions,[17] would not be cost-effective in the US, even among current smokers (Supplemental Table 3). While such a test would lead to similar reductions in cancer risk as regular screening, nearly 30% as opposed to 2% would have a false positive test and receive treatment unnecessarily leading to higher costs and possible harm without a commensurate gain in benefits. Similar to our threshold analyses on screening test characteristics (Figure 4), these results highlight the importance of accurately detecting the absence of atrophy or precancerous lesions for any serum pepsinogen test-based screening strategy.

Previous studies have concluded H. pylori screening is cost-effective in the US.[21, 83] Our findings provide updated estimates of the cost-effectiveness of population-based H. pylori screening based on randomized trial evidence that only individuals without existing precancerous lesions benefit from H. pylori treatment.[20] Under this assumption, we found that targeting screening to 20-year old individuals (who are less likely to have precancerous lesions) may be more effective in reducing cancer risk (1.6% vs. 0.2%). However, even with the greater benefit, the strategy would remain unattractive compared to no screening (ICER = $2.7M per QALY) and dominated by serum pepsinogen screening. Recent results from another randomized trial in China suggest that all individuals, regardless of the presence of advanced lesions, may benefit from H. pylori treatment,[84] potentially as a result of eradicating non-H. pylori bacteria that influence the later stages of gastric carcinogenesis [85]. If we assumed that the risk of dysplasia was reduced by 50% among all treated individuals, H. pylori screening was indeed more attractive compared to no screening (21% reduction in cancer risk at an ICER of $85,000 per QALY). Yet, H. pylori screening was still dominated by serum pepsinogen screening as the reduction in cancer risk was also greater for serum pepsinogen screening (44%) and at a more favorable ICER ($70,700 per QALY). As such, despite the considerable uncertainty in H. pylori treatment effectiveness, our findings suggest that serum pepsinogen is likely to be a more effective and cost-effective NCGA screening strategy in the US.

Limitations to our study include using data from multiple sources with varying study designs. We conducted extensive probabilistic sensitivity analyses to account for the uncertainty in variables and assumptions, including disease natural history. We focused on only men, and made the simplifying assumption that the prevalence of H. pylori and smoking were independent because data regarding interactions are not available. We also only focused on one gastric cancer subtype. If we assumed that diffuse and other noncardia tumors (detectable for 24 months on average before becoming clinically symptomatic) were also detected via follow-up endoscopy for a positive serum pepsinogen screen, results were largely unchanged (ICER = $104,100 vs. $105,400 in the base case). This was consistent with our finding that the majority of serum pepsinogen screening benefit was derived from the detection and removal of dysplastic lesions before they progressed to invasive cancer. We found however, that serum pepsinogen screening was less attractive if treated individuals still harbored intestinal metaplastic lesions (common in settings where H. pylori-related atrophy is frequently multifocal) or if endoscopic sensitivity for dysplasia was considerably lower. However, as long as sensitivity was greater than 60% (base case = 81%), serum pepsinogen screening remained attractive for current smokers (ICER = $99,400).

Notably, we based estimates of serum pepsinogen test performance and EMR treatment effectiveness on clinical studies from Japan given the limited data in Western populations. EMR is relative new, availability of and expertise with EMR technology is limited; additional training (and resources) will be needed to realize the projected screening benefits. Not all biopsy-detected dysplasia may be macroscopically visible and therefore, eligible for EMR. We found however that even if the large majority of individuals with dysplasia (60–70%) would require annual or biannual endoscopic surveillance before undergoing EMR treatment, results were largely unchanged. We also did not include the impact of endoscopy-related incidental findings and their downstream effects in our analysis; further analysis of their long-term effects is needed. Proton-pump inhibitors, widely used in the general population, may reduce serum pepsinogen test sensitivity by altering intragastric acidity and biomarker levels.[86] Sensitivity analyses found that even if sensitivity fell to 60% (base case = 71%), as long as test specificity was greater than 94%, the ICER remained attractive for current smokers.

Lastly, our model focused on NCGA screening in the US. Estimates of the clinical benefits and cost-effectiveness associated with screening strategies will vary in high-risk countries, such as Japan, where risk factor prevalence and influence on the multifactorial etiology of gastric carcinogenesis may differ. As the projective validity of our model was consistent with data on precancerous lesions prevalence and cancer risk from the Netherlands, our findings are likely generalizable to this setting and other low-risk European countries with similar H. pylori and smoking profiles.[87]

Our model-based findings suggest that serum pepsinogen screening to reduce NCGA risk is not warranted for the general population. However, targeting high-risk smokers for screening may be an effective and cost-effective strategy to reduce intestinal-type NCGA mortality. Further, the marginal benefits associated with H. pylori screening, even among high risk subgroups, underscore the need for future clinical studies on alternative secondary gastric cancer control strategies, including serum pepsinogen screening, to improve cancer outcomes and overall survival.

Supplementary Material

SUMMARY BOX.

What is already known about this subject?

Gastric cancer rates are declining, but more than 20,000 cases are diagnosed each year in the US and noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma (NCGA) remains the leading subtype.

Screening for precursors of NCGA may be an effective strategy for preventing disease and reducing cancer deaths among US men, yet long-term benefits associated with new biomarkers and endoscopic technologies are uncertain.

What are the new findings?

Although a one-time serum pepsinogen screen at age 50 may prevent 1 in 4 intestinal-type NCGAs among men, population-based screening for the general population is unlikely to be a high-value approach for improving cancer outcomes.

However, targeting high-risk smokers may be a cost-effective strategy to reduce NCGA deaths and warrants consideration.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Our model-based findings suggest screening current smokers with a serum pepsinogen test may be an effective and cost-effective strategy to identify men at elevated risk for NCGA who may benefit from endoscopic follow-up and treatment.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

Dr. Yeh was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant K07CA143044. The funder had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Abbreviations

- EMR

endoscopic mucosal resection

- H. pylori

Helicobacter pylori

- ICER

incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- NCGA

noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma

- NNS

number needed to screen

- QALY

quality-adjusted-life-year

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

CONTRIBUTIONS

JMY, CH, ZW, DS, SJG conceived and designed the study; analyzed and interpreted the data; drafted and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; and approved the version to be published. All authors had full access to all the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. JMY is the guarantor.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not required.

DATA SHARING

No additional data available.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2011. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2014. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/, based on November 2013 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizoue T, Yoshimura T, Tokui N, et al. Prospective study of screening for stomach cancer in Japan. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:103–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llorens P. Gastric cancer mass survey in Chile. Semin Surg Oncol. 1991;7:339–43. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980070604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pisani P, Oliver WE, Parkin DM, et al. Case-control study of gastric cancer screening in Venezuela. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:1102–5. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Correa P, Haenszel W, Cuello C, et al. A model for gastric cancer epidemiology. Lancet. 1975;2:58–60. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)90498-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:607–15. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chao A, Thun MJ, Henley SJ, et al. Cigarette smoking, use of other tobacco products and stomach cancer mortality in US adults: The Cancer Prevention Study II. Int J Cancer. 2002;101:380–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kneller RW, You WC, Chang YS, et al. Cigarette smoking and other risk factors for progression of precancerous stomach lesions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84:1261–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.16.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russo A, Maconi G, Spinelli P, et al. Effect of lifestyle, smoking, and diet on development of intestinal metaplasia in H. pylori-positive subjects. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1402–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato I, Vivas J, Plummer M, et al. Environmental factors in Helicobacter pylori-related gastric precancerous lesions in Venezuela. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:468–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samloff IM, Varis K, Ihamaki T, et al. Relationships among serum pepsinogen I, serum pepsinogen II, and gastric mucosal histology. A study in relatives of patients with pernicious anemia. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:204–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Correa P, Piazuelo MB, Wilson KT. Pathology of gastric intestinal metaplasia: clinical implications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:493–8. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.den Hoed CM, van Eijck BC, Capelle LG, et al. The prevalence of premalignant gastric lesions in asymptomatic patients: predicting the future incidence of gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1211–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miki K, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, et al. Long-term results of gastric cancer screening using the serum pepsinogen test method among an asymptomatic middle-aged Japanese population. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:78–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2009.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dinis-Ribeiro M, Yamaki G, Miki K, et al. Meta-analysis on the validity of pepsinogen test for gastric carcinoma, dysplasia or chronic atrophic gastritis screening. J Med Screen. 2004;11:141–7. doi: 10.1258/0969141041732184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Storskrubb T, Aro P, Ronkainen J, et al. Serum biomarkers provide an accurate method for diagnosis of atrophic gastritis in a general population: The Kalixanda study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1448–55. doi: 10.1080/00365520802273025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeh JM, Hur C, Kuntz KM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treatment and endoscopic surveillance of precancerous lesions to prevent gastric cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:2941–53. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsonnet J, Harris RA, Hack HM, et al. Modelling cost-effectiveness of Helicobacter pylori screening to prevent gastric cancer: a mandate for clinical trials. Lancet. 1996;348:150–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)01501-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeh JM, Hur C, Schrag D, et al. Contribution of H. pylori and smoking trends to US incidence of intestinal-type noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma: a microsimulation model. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fennerty MB, Emerson JC, Sampliner RE, et al. Gastric intestinal metaplasia in ethnic groups in the southwestern United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1992;1:293–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch; SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 9 Regs Research Data, Nov 2010 Sub (1973–2008) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment> - Linked To County Attributes - Total U.S., 1969–2009 Counties. ( www.seer.cancer.gov) released April 2011, based on the November 2010 submission. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russel LB, et al., editors. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eichler HG, Kong SX, Gerth WC, et al. Use of cost-effectiveness analysis in health-care resource allocation decision-making: how are cost-effectiveness thresholds expected to emerge? Value Health. 2004;7:518–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.75003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neumann PJ, Sandberg EA, Bell CM, et al. Are pharmaceuticals cost-effective? A review of the evidence. Health Aff (Millwood) 2000;19:92–109. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.2.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guarner J, Bartlett J, Whistler T, et al. Can pre-neoplastic lesions be detected in gastric biopsies of children with Helicobacter pylori infection? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:309–14. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200309000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeh JM, Hur C, Schrag D, et al. Contribution of H. pylori and smoking trends to US incidence of intestinal-type noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma: a microsimulation model. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kruszon-Moran D, McQuillan GM. Seroprevalence of six infectious diseases among adults in the United States by race/ethnicity: data from the third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988–94. Adv Data. 2005:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoenborn CA, Adams PE. Health behaviors of adults: United States, 2005–2007. Vital Health Stat. 2010;10:1–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson CM, Burns DM, Dodd KW, et al. Chapter 2: Birth-cohort-specific estimates of smoking behaviors for the U.S. population. Risk Anal. 2012;32(Suppl 1):S14–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenberg MA, Feuer EJ, Yu B, et al. Chapter 3: Cohort life tables by smoking status, removing lung cancer as a cause of death. Risk Anal. 2012;32(Suppl 1):S25–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banatvala N, Mayo K, Megraud F, et al. The cohort effect and Helicobacter pylori. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:219–21. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuipers EJ, Uyterlinde AM, Pena AS, et al. Long-term sequelae of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Lancet. 1995;345:1525–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xia HH, Talley NJ. Natural acquisition and spontaneous elimination of Helicobacter pylori infection: clinical implications. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1780–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gisbert JP. The recurrence of Helicobacter pylori infection: incidence and variables influencing it. A critical review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2083–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. DHHS Publication No. (CDC) 90-8416. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. Centers for Disease Control. Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Office of Smoking and Health; 1990. The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- 39. [Accessed on September 24, 2013];The Berkeley Mortality Database. Available at http://www.demog.berkeley.edu/~bmd/

- 40.Bell FC, Miller ML. SSA Pub No 11–11536. Baltimore, MD: Social Security Administration, Office of the Chief Actuary; 2005. Life tables for the United States Social Security area 1900–2100. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thun MJ, Myers DG, Day-Lally C, et al. Chapter 5: Age and the Exposure-Response Relationships Between Cigarette Smoking and Premature Death in Cancer Prevention Study II. In: Burns DM, Garfinkel L, Samet JM, editors. Changes in Cigarette Related Disease Risks and Their Implication for Prevention and Control. Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No 8 NIH Publication No 97-4213. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ladeiras-Lopes R, Pereira AK, Nogueira A, et al. Smoking and gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:689–701. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9132-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rockhill B, Newman B, Weinberg C. Use and misuse of population attributable fractions. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:15–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Vries AC, van Grieken NC, Looman CW, et al. Gastric cancer risk in patients with premalignant gastric lesions: a nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:945–52. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Vries AC, Haringsma J, de Vries RA, et al. Biopsy strategies for endoscopic surveillance of pre-malignant gastric lesions. Helicobacter. 2010;15:259–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watanabe Y, Ozasa K, Higashi A, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and atrophic gastritis. A case-control study in a rural town of Japan. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:391–4. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199707000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burucoa C, Delchier JC, Courillon-Mallet A, et al. Comparative evaluation of 29 commercial Helicobacter pylori serological kits. Helicobacter. 2013;18:169–79. doi: 10.1111/hel.12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loy CT, Irwig LM, Katelaris PH, et al. Do commercial serological kits for Helicobacter pylori infection differ in accuracy? A meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1138–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guarner J, Herrera-Goepfert R, Mohar A, et al. Diagnostic yield of gastric biopsy specimens when screening for preneoplastic lesions. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:28–31. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2003.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hosokawa O, Miyanaga T, Kaizaki Y, et al. Decreased death from gastric cancer by endoscopic screening: Association with a population-based cancer registry. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1112–5. doi: 10.1080/00365520802085395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schauer PR, Schwesinger WH, Page CP, et al. Complications of surgical endoscopy. A decade of experience from a surgical residency training program. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:8–11. doi: 10.1007/s004649900284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim SY, Sung JK, Moon HS, et al. Is endoscopic mucosal resection a sufficient treatment for low-grade gastric epithelial dysplasia? Gut Liver. 2012;6:446–51. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2012.6.4.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahn JY, Jung HY, Choi KD, et al. Endoscopic and oncologic outcomes after endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: 1370 cases of absolute and extended indications. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:485–93. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bennett C, Wang Y, Pan T. Endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD004276. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004276.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kojima T, Parra-Blanco A, Takahashi H, et al. Outcome of endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: review of the Japanese literature. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:550–4. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70108-7. discussion 554–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glance LG, Lustik SJ, Hannan EL, et al. The Surgical Mortality Probability Model: derivation and validation of a simple risk prediction rule for noncardiac surgery. Ann Surg. 2012;255:696–702. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824b45af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi KS, Jung HY, Choi KD, et al. EMR versus gastrectomy for intramucosal gastric cancer: comparison of long-term outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:942–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hanmer J, Lawrence WF, Anderson JP, et al. Report of nationally representative values for the noninstitutionalized US adult population for 7 health-related quality-of-life scores. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:391–400. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06290497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gold MR, Franks P, McCoy KI, et al. Toward consistency in cost-utility analyses: using national measures to create condition-specific values. Med Care. 1998;36:778–92. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199806000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed on February 1, 2013];Research, Statistics, Data & Systems. 2012 http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems.html.

- 61.RED BOOK Online™. Truven Health Analytics. Micromedex Solutions; 2013. [Accessed on February 28, 2013]. http://micromedex.com/redbook. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:630–41. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Employment and Wages. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; [Accessed Feburary 15, 2013]. http://www.bls.gov/oes/ [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yabroff KR, Davis WW, Lamont EB, et al. Patient time costs associated with cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:14–23. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McNicholl AG, Linares PM, Nyssen OP, et al. Meta-analysis: esomeprazole or rabeprazole vs first-generation pump inhibitors in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:414–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thun MJ, Carter BD, Feskanich D, et al. 50-year trends in smoking-related mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:351–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dan YY, So JB, Yeoh KG. Endoscopic screening for gastric cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:709–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dinis-Ribeiro M, da Costa-Pereira A, Lopes C, et al. Feasibility and cost-effectiveness of using magnification chromoendoscopy and pepsinogen serum levels for the follow-up of patients with atrophic chronic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1594–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lomba-Viana R, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Fonseca F, et al. Serum pepsinogen test for early detection of gastric cancer in a European country. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:37–41. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834d0a0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yanaoka K, Oka M, Mukoubayashi C, et al. Cancer high-risk subjects identified by serum pepsinogen tests: outcomes after 10-year follow-up in asymptomatic middle-aged males. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:838–45. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oishi Y, Kiyohara Y, Kubo M, et al. The serum pepsinogen test as a predictor of gastric cancer: the Hisayama study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:629–37. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miki K, Morita M, Sasajima M, et al. Usefulness of gastric cancer screening using the serum pepsinogen test method. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:735–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mizuno S, Kobayashi M, Tomita S, et al. Validation of the pepsinogen test method for gastric cancer screening using a follow-up study. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:158–63. doi: 10.1007/s10120-009-0522-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shikata K, Ninomiya T, Yonemoto K, et al. Optimal cutoff value of the serum pepsinogen level for prediction of gastric cancer incidence: the Hisayama Study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:669–75. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.658855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Correa P. Serum pepsinogens in gastric cancer screening. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2123–5. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1248-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miki K, Urita Y. Using serum pepsinogens wisely in a clinical practice. J Dig Dis. 2007;8:8–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-9573.2007.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Church TR, Black WC, Aberle DR, et al. Results of initial low-dose computed tomographic screening for lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1980–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Humphrey LL, Deffebach M, Pappas M, et al. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography: a systematic review to update the US Preventive services task force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:411–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-6-201309170-00690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schoen RE, Pinsky PF, Weissfeld JL, et al. Colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality with screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2345–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Miki K, Fujishiro M. Cautious comparison between East and West is necessary in terms of the serum pepsinogen test. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:134–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2009.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fendrick AM, Chernew ME, Hirth RA, et al. Clinical and economic effects of population-based Helicobacter pylori screening to prevent gastric cancer. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:142–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li WQ, Ma JL, Zhang L, et al. Effects of Helicobacter pylori treatment on gastric cancer incidence and mortality in subgroups. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju116. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Freedberg DE, Abrams JA, Wang TC. Prevention of gastric cancer with antibiotics: can it be done without eradicating Helicobacter pylori? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju148. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Agreus L, Storskrubb T, Aro P, et al. Clinical use of proton-pump inhibitors but not H2-blockers or antacid/alginates raises the serum levels of amidated gastrin-17, pepsinogen I and pepsinogen II in a random adult population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:564–70. doi: 10.1080/00365520902745062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lunet N, Barros H. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer: facing the enigmas. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:953–60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.