Abstract

Skin development requires communication between epithelial and mesenchymal cells, melanocytes and neurons. Sennett et al. (2015) shed new light on these mechanisms by simultaneously profiling multiple different cell types in embryonic mouse skin at the onset of hair follicle formation.

Ever since the publication of Margaret Hardy’s classic review on hair follicle morphogenesis (Hardy, 1992), biologists have turned to this mini-organ as an accessible and intricately beautiful model system for unraveling general principles of development, regenerative growth, and adult stem cell behavior. Delineating the mechanisms by which hair follicles develop in the embryo remains an area of great interest. Although we understand the basic mechanisms by which epithelial and mesenchymal cells communicate during hair follicle morphogenesis, precisely how this cross-talk results in a functioning, multi-layered hair follicle is still unclear. Little is known of the signals by which emerging hair follicles communicate and coordinate with other cell types in the skin such as nerve fibers and melanocytes. Regional differences in hair follicles, for instance in the size and androgen responsiveness of human scalp versus body hair, are thought to be dictated by signals from the dermis (Hardy, 1992); however, the signaling interactions involved in establishing this variation are virtually unknown. Furthermore, the regulatory factors that control formation of hair follicles versus sweat glands, and how these have evolved to match the needs of different mammalian species, remain obscure. Solving these puzzles will be important in the quest to regenerate normally functioning skin for therapeutic purposes. In an elegant Resource study in this issue of Developmental Cell, Sennett et al. (2015) provide fresh insight into some of these questions by simultaneously profiling multiple different cell types in embryonic mouse skin at a single, critical time point, when hair follicles first start to develop.

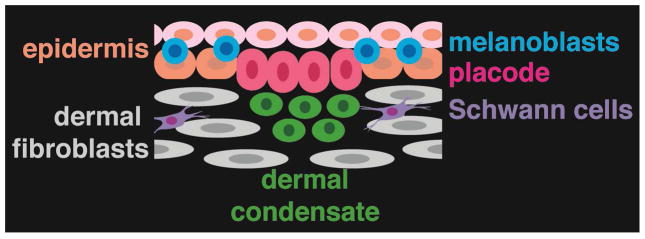

The earliest morphological sign of hair follicle formation is the appearance of a thickening, or placode, in the surface ectoderm. Almost simultaneously, dermal cells under the placode coalesce to form a dermal condensate (DC), the precursor of the hair follicle dermal papilla (DP) (Figure 1). Subsequent signaling from the DC is required for proliferation and downgrowth of the follicle. Secreted signaling molecules mediate interactions of developing hair follicles with their environment as well as the communications required for morphogenesis.

Figure 1.

Cell types in embryonic mouse skin at E14.5.

Gene expression analyses form an important foundation for delineating these signaling mechanisms. The first studies in this area relied on labor-intensive in situ hybridization and immunostaining techniques. While such approaches could identify only limited numbers of candidate genes, they were informative, leading to functional analyses that defined major signaling pathways required for hair follicle development. These include Wnt signaling through the canonical β-catenin pathway, which is essential in both epithelial and dermal cells for hair follicle formation (Tsai et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2009). Activation of the Eda/Edar pathway, mutated in the majority of human ectodermal dysplasias, operates immediately downstream of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and maintains primary hair placodes in embryonic mouse skin. Eda/Edar signaling is required for expression of Sonic hedgehog (Shh), which in turn promotes development of the DC into a DP and hair follicle epithelial proliferation and downgrowth (Zhang et al., 2009). Subsequent microarray-based transcriptional profiling studies of EDA-A1-treated skin explants lead to identification of FGF20 as a key epithelial signal that induces DC formation (Huh et al., 2013). Rendl et al. developed sophisticated profiling approaches using transgenic technology and immunolabelling to purify dermal fibroblasts, melanocytes and hair follicle matrix cells, outer root sheath cells and DP from mouse skin at postnatal day 4. By examining multiple cell types at the same time point, this study revealed potential interactions of mesenchymal and epithelial cells at early stages of postnatal hair growth (Rendl et al., 2005).

In the current paper, Sennett et al. (2015) undertake the ambitious goal of simultaneously profiling all of the cells in the skin at a single embryonic time point when hair follicles first start to develop. This global approach allows inference of signaling interactions between multiple different cell types, and provides an advance over earlier studies of embryonic hair follicles that focused on either the epithelial or mesenchymal compartment, or utilized mixed cell populations. Sennett et al. (2015) also use next generation RNA-sequencing for transcriptional profiling, which provides a less biased and more quantitative analysis than the microarray-based approaches employed in most of the prior studies. For FACS isolation of specific cell types, the authors utilized a novel combination of immunolabelling with anti-E-cadherin and P-cadherin together with transgenic expression of Sox2GFP and Lef1-RFP that allowed them to separate placode cells, DCs, melanocytes, interfollicular keratinocytes, non-DC fibroblasts, Schwann cells, and all remaining cells, which were a mixture of endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and unidentified dermal cells. Importantly, the authors were able to define new molecular signatures for each of the specifically isolated populations. Placode-specific genes included Crim1 and Kremen2, which modulate signaling, gap junction and calcium sensing genes, and the transcription factor gene Sox21. DC-expressed genes included many associated with Shh and Fgf signaling, Dclk1, encoding a kinase implicated in cell migration, and transcription factors of the SOX and FOX families. Mining of the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway database revealed distributions of ligand, receptor, and inhibitor expression for pathways of known importance in morphogenesis. The authors also identified DC-specific expression of potentially significant novel factors including axon guidance regulators involved in chemokine, Semaphorin, Neuropilin, Netrin, Ephrin, and Slit/Robo signaling, suggesting involvement of these pathways in sorting and clustering of cells to form the DC and/or in guiding Schwann cells to developing hair follicles.

The hair follicle placode gives rise to all of the epithelial lineages of the hair follicle, including the adult hair follicle bulge epithelial stem cell compartment (Levy et al., 2005). The new dataset provided by Sennett et al. (2015) allows these authors to explore whether hair follicle embryonic precursors have similar transcriptional characteristics to previously characterized adult hair stem cells and their DP niche. Interestingly, the authors find little overlap in gene expression between placodes and bulge stem cells (13 genes). This finding is consistent with the observation that bulge formation is dependent on Sox9, which is expressed in hair follicle epithelial cells after the placode stage (Nowak et al., 2008). Comparison of the DC and adult DP identified only 31 overlapping genes, suggesting that DC cells undergo major changes as they develop into the DP, and consistent with observations of heterogeneous cell types within the adult DP. By contrast, embryonic and postnatal melanocytes had relatively similar gene expression patterns.

A major strength of this study is the development and ready availability of a companion website, Hair-gel (http://hair-gel.net/) that has been optimized for use on mobile as well as standard devices and provides an easily searchable gene expression database and a link to the raw data. Such a resource has been lacking in the hair biology field, and its usefulness may be inferred from the popularity of a similar site called Bite-it (http://bite-it.helsinki.fi/) that provides expression data on developing teeth (hosted by the Tooth and Craniofacial Development Group at the University of Helsinki). Access to such data, together with the advent of CRISPR/Cas9 technology, will significantly accelerate the pace of functional analyses of skin morphogenesis and the development of new tools for visualizing, and tracing the lineages of, specific cell populations. In the future it will be of interest to employ similar approaches to explore the molecular basis of regional differences, for instance in dorsal versus ventral, and hairy versus non-hairy skin. Extending these analyses to include miRNAs and lncRNAs, which are increasingly recognized as playing key roles in stem cell function and differentiation, will also be valuable.

Skin development is a highly dynamic process. The availability of fluorescent reporters of gene expression, cell cycle stage, and signaling pathway activity, and exciting recent advances in live imaging of skin tissues (Ahtiainen et al., 2014; Rompolas et al., 2012), are now making it possible to monitor changes in expression patterns and visualize their affects on signaling, cell division, and cell movements, in real time. Sennett et al.’s fascinating “snapshot” of gene activity will facilitate such studies, and provides us with an exciting preview of Technicolor movies yet to come.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahtiainen L, Lefebvre S, Lindfors PH, Renvoise E, Shirokova V, Vartiainen MK, Thesleff I, Mikkola ML. Dev Cell. 2014;28:588–602. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy MH. Trends in Genetics. 1992;8:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90350-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh SH, Narhi K, Lindfors PH, Haara O, Yang L, Ornitz DM, Mikkola ML. Genes Dev. 2013;27:450–458. doi: 10.1101/gad.198945.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy V, Lindon C, Harfe BD, Morgan BA. Dev Cell. 2005;9:855–861. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak JA, Polak L, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendl M, Lewis L, Fuchs E. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rompolas P, Deschene ER, Zito G, Gonzalez DG, Saotome I, Haberman AM, Greco V. Nature. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nature11218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, et al. Dev Cell this issue. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SY, Sennett R, Rezza A, Clavel C, Grisanti L, Zemla R, Najam S, Rendl M. Dev Biol. 2014;385:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Tomann P, Andl T, Gallant NM, Huelsken J, Jerchow B, Birchmeier W, Paus R, Piccolo S, Mikkola ML, et al. Dev Cell. 2009;17:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]