Abstract

Background

Bundled payments, also known as episode-based payments, are intended to contain health care costs and promote quality. In 2011 a bundled payment pilot program for total hip replacement was implemented by an integrated health care delivery system in conjunction with a commercial health plan subsidiary. In July 2015 the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) proposed the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model to test bundled payment for hip and knee replacement.

Methods

Stakeholders were identified and a structure for program development and implementation was created. An Oversight Committee provided governance over a Clinical Model Subgroup and a Financial Model Subgroup.

Results

The pilot program included (1) a clinical model of care encompassing the period from the preoperative evaluation through the third postoperative visit, (2) a pricing model, (3) a program to share savings, and (4) a patient engagement and expectation strategy. Compared to 32 historical controls— patients treated before bundle implementation—45 post-bundle-implementation patients with total hip replacement had a similar length of hospital stay (3.0 versus 3.4 days, p = .24), higher rates of discharge to home or home with services than to a rehabilitation facility (87% versus 63%), similar adjusted median total payments ($22,272 versus $22,567, p = .43), and lower median posthospital payments ($704 versus $1,121, p = .002), and were more likely to receive guideline-consistent care (99% versus 95%, p = .05).

Discussion

The bundled payment pilot program was associated with similar total costs, decreased posthospital costs, fewer discharges to rehabilitation facilities, and improved quality. Successful implementation of the program hinged on buy-in from stakeholders and close collaboration between stakeholders and the clinical and financial teams.

Bundled payments, also known as episode-based payments, represent the reimbursement of health care providers for projected costs over a distinct episode of care.1–4 They are an alternative to the current fee-for-service payment system, in which hospitals and physicians are paid for each service provided. 5–7 A number of health systems have begun to report their experience with bundled payments, both with private payers and with Medicare,3 and states such as Arkansas and Massachusetts have fostered the development of bundled payment programs as a key health care reform strategy.7,8 Bundled payments are now being scaled to the national level in the United States, as the Affordable Care Act specifies that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) implement a bundled payment pilot program.9 In August 2011 CMS released a request for applications for the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative, in advance of the national pilot program. In its request, CMS stated that bundled payments are “one way to encourage physicians, hospitals, and other health care providers to work together to better coordinate care for patients when they are in the hospital and after they are discharged.” 10 As of July 2014, there were 105 providers—hospitals, physicians, and postacute agencies—in the “risk-bearing” phase of the CMS bundled payment program, and 6,424 providers in the non–risk bearing phase, many of whom are expected undertake some risk starting in 2015.11 In July 2015 CMS announced a proposal for the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model, which would test bundled payment for hip and knee replacement by requiring all hospitals to participate in 75 geographic areas.12

Despite high levels of enthusiasm for bundled payment programs,1,2 their impact on clinical and financial outcomes remains uncertain. Furthermore, the best approach to creating and implementing such a program is not well established. In this article, we describe our health system’s experience developing and implementing a bundled payment program and examine its effects on quality and cost for patients undergoing total hip replacement. In addition to reporting our results, we also hope to assist organizations that might be considering developing bundled payment programs for their patients.

Methods

Setting and Participants

On January 1, 2011, Baystate Health, an integrated health care delivery system in western Massachusetts, commenced a total hip replacement bundled payment program with an independent group of orthopedic surgeons from Springfield (New England Orthopedic Surgeons). Before program development, the leadership of Baystate Health identified the establishment of bundled payment programs as an organizational strategic goal. The aim of the program was to develop a model process for creating and implementing bundled payments and test whether such an approach for total hip replacement could lower costs while maintaining or improving quality.

We identified primary stakeholders and included them as participants in the program, including New England Orthopedic Surgeons and three affiliates of Baystate Health—Baystate Medical Center (the single hospital where the study was conducted), Health New England (a provider-sponsored health plan), and Baystate Visiting Nurse Association and Hospice. In May 2010 we convened an Oversight Committee representing the participating groups to develop the bundled payment program for total hip replacement. The Oversight Committee, which consisted of approximately 10 members [including W.F.W, R.J.K., A.P.L., S.C., E.B., J.M.*], provided governance over two distinct subgroups, each consisting of approximately six members, as follows:

The Clinical Model Subgroup [including W.F.W., R.J.K., A.P.L., J.G., S.C., J.M.], which focused on developing the clinical elements of the bundle

The Financial Model Subgroup [including W.F.W., S.C., J.M.], which generated a price for the bundle (see the description of the reimbursement model, page 409).

After seven months of coordinated planning between these groups, the bundled payment pilot began on January 1, 2011, and continued through December 31, 2011. The Baystate Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this evaluation with a waiver of informed consent.

Before the bundle period, New England Orthopedic Surgeons held a medical directorship with a stipend for the total joint replacement orthopedic service line at Baystate Medical Center. This arrangement did not change during the bundle period. Before and during the bundle program, there were medical director and laboratory contractual relationships, but no ownership or formal affiliation, between Baystate Health and the main referral skilled nursing facility.

Development of the Clinical Model

The Clinical Model Subgroup of the Oversight Committee was responsible for developing the elements of clinical care for the time period encompassed by the bundled payment. The subgroup based the clinical model on evidence and/or consensus, drawing on previous work accomplished in the organization, national quality measures, and modifications based on goals for the program.1 We created an order set in the hospital electronic health record to ensure adherence to the intended treatment plan.

Development of the Financial Model

The Financial Model Subgroup was tasked with establishing the component parts of the bundled payment program, generating a price for the bundle, and distributing savings. This subgroup began by examining all payments made by the health plan to the provider entities (for example, physicians, radiology, pharmacy, durable medical equipment, hospital, Visiting Nurse Association, rehabilitation facility, ambulance) for the diagnosis codes corresponding to total hip replacement. Then, in coordination with the Clinical Model Subgroup, it narrowed down the elements to be included in the bundle. After the bundle components were established, this subgroup sought to derive an overall price for the bundle, representing the sum of the components.

Outcomes

Quality of care was measured using established national metrics in the domains of care processes, harm, mortality, and 30-day readmissions. We obtained surgical quality metrics from data routinely collected for quality improvement purposes, including Surgical Care Improvement Project measures,13 relevant Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Patient Safety Indicators,14 and CMS Hospital-Acquired Conditions. 15 We extracted data on length of stay (LOS) from Baystate Health’s billing software. We obtained data on hospital payments, physician payments, posthospital payments, and total payment directly from Health New England, the payer. Of note, there was a change in the diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment method just before the start of the bundle period. Moreover, the patients included were insured by Health New England in any of three payment groups. Payments included a DRG base payment (defined for each payment plan) multiplied by a DRG weight. Because both the DRG base amounts and the DRG weight changed for all three patient groups, we adjusted hospital payments for each patient in the baseline (pre-bundle) period, using the DRG base and weights from the bundle period. This would “adjust down” the baseline payments, removing the effect of DRG changes and allowing comparison of payments between pre- and bundle periods.

Data Analysis

We compared patient characteristics and outcomes for patients during the bundle period (calendar year 2011) to patients treated in the year before implementation of the bundle (2010) using chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test for categorical factors, or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for age, LOS, and payments.

Results

Oversight Committee

Given the complexity of the program, the Oversight Committee believed that using the simplest and narrowest definition of bundle components would increase the bundle’s chances for success. Our approach to the structure of the bundle, therefore, was to limit inclusion to services that were directly related to the procedure itself and that could favorably influence costs under a shared savings model (Sidebar 1, above). For example, for services provided by the orthopedic surgery practice, a preoperative visit with a plain x-ray, and three postoperative visits (each with a plain x-ray if indicated) were included. For posthospital services, skilled nursing facility rehabilitation, outpatient physical therapy, and visiting nurse visits were included. We provided clear guidelines as to the duration and intensity of the posthospital services, with the goal of eliminating services (such as prolonged nursing facility stays) for which there was no evidence of benefit.

Sidebar 1. Elements of the Bundled Payment Program.

Services and Procedures Included in the Bundled Payment

Payment to orthopedic surgeon for procedure (includes one postoperative visit)

Surgeon preoperative and two postoperative visits

Plain x-ray at each surgeon visit

Preoperative education class

Preoperative physical therapy visit

Acute care hospitalization, including surgical procedure

Ambulance transport from hospital to nursing facility

Skilled nursing facility rehabilitation

Outpatient physical therapy

Outpatient occupational therapy

Services and Procedures Excluded from the Bundled Payment

Nonorthopedic surgeon physician fees

Outpatient drugs

Durable medical equipment

All other postacute services

Clinical Model

The bundle was initiated after the surgeon had identified the need for a total hip replacement. We chose to define bundle duration according to the period of services in support of the episode instead of a discrete time period (for example, 90 days) to allow the providers and patients more flexibility. The Clinical Model Subgroup specified bundle components, beginning with the orthopedist’s preoperative history and physical, and concluding with the third postoperative office follow-up visit. If the patient progressed well postoperatively, the program aimed for hospital discharge two days after surgery. The final service provided— the third postoperative visit—was generally scheduled for approximately 10–14 weeks after the date of surgery. The subgroup elected not to include the purchase of durable medical equipment, such as a walker, in the bundle because some patients obtained it before admission, while others received it in hospital or after discharge, making costs difficult to capture and align with pricing. We did not provide a bundle warranty. The health plan, which is owned by the health system, would be responsible for the costs of postoperative complications, such as a surgical site infection.

The Clinical Model Subgroup determined that discharging appropriate patients directly to home instead of to a rehabilitation facility represented an opportunity for cost savings and quality improvement. Accordingly, patients were educated about the benefits of discharge directly to home (educational materials were updated accordingly), and it was agreed that the program would furnish extra home physical therapy services (as described on page 409) for patients discharged directly to home. The main changes to the model of care during the bundle period, therefore, included aiming to discharge a subset of rapidly progressing patients after two hospital days (instead of the usual three days) and to provide interventions to discharge patients directly to home if appropriate. The hospital team—physician, case manager, physical therapist, nurse—collaborated to provide consistent messaging to patients regarding the plan for a home discharge.

An effort was made to schedule the surgery early in the day, with the goal of beginning physical therapy the afternoon of surgery and discharging the patient two or three days after surgery. The model specified hospital care elements, including vital signs, wound care, pain control, perioperative antibiotics, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, physical/occupational therapy, patient teaching, and medication reconciliation. After the patient was ready for discharge, published appropriateness criteria were used to determine whether he or she would go home or to a facility,16 as follows:

If the patient was discharged home two days after surgery, the model called for eight home physical therapy visits.

For discharge home three days after surgery, six home physical therapy visits were included.

For discharge first to a rehabilitation facility, four home physical therapy visits after facility discharge were included.

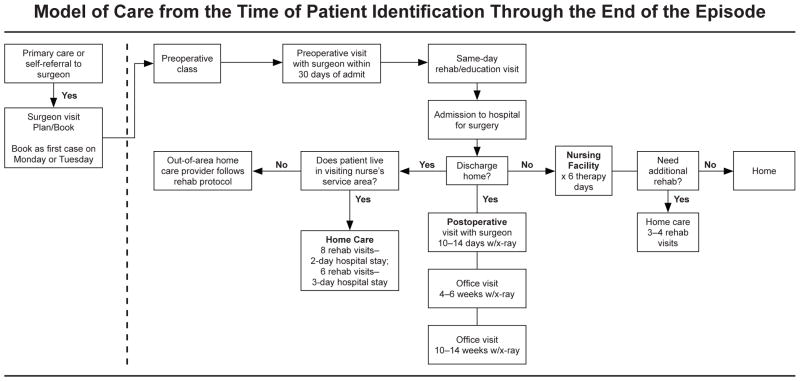

As can be seen from the criteria, the care model during the bundle period was prescriptive as to the number of posthospital skilled nursing days and duration of physical therapy, including specifying number of home therapy visits on the basis of hospital LOS and whether the patient had a stay in a skilled nursing facility (Figure 1, above).

Figure 1.

Preoperative preparation included education, scheduling, surgeon visit, and rehabilitation evaluation. Posthospital physical therapy duration and frequency with home care, which varied according to hospital length of stay, and skilled nursing facility was specified, as were three posthospital surgeon visits, after which the episode concluded. Rehab, rehabilitation.

Financial Model

The program’s main goal was to provide an incentive to the physicians and the hospital to provide efficient care, such that these parties would share any savings realized through costs incurred below the target bundle price. The program was structured to allow a fee-for-service payment with an end-of-the-year financial reconciliation that compared the actual costs of the bundle price to anticipated costs. If there were funds left over as a result of lower actual costs compared to the bundle price, they would be placed into a shared savings pool. We opted for this retrospective approach because of challenges associated with changing the payment structure for a relatively small subset of all patients receiving total hip replacement.

Because the program was structured as a pilot, there was also no financial risk to the participating provider entities, including the orthopedic surgeons and the hospital, if costs were higher than projected. Initial formulations of the program specified that savings be shared equally between the physicians and hospital. The Financial Model Subgroup decided on equal sharing of savings between the parties to recognize the partnership between the two, in which each partner’s role in achieving the program’s goals is of equal importance. After discussion, the program sought to align incentives more closely with the Visiting Nurse Association, so that in the final determination, they, too, were included in the shared savings. The shared savings scheme allotted funds as follows: 45% to the physicians, 45% to the hospital, and 10% to the Visiting Nurse Association. Notably, the Financial Model Subgroup did not work on contracting activities to lower the cost of hip implants, as is common for some bundled payment programs, because such work had been completed before program development. Therefore, the cost of the implants was the same before and during the bundle period.

Patient Eligibility

The Clinical Model Subgroup established that all Health New England patients determined to be eligible for total hip replacement would be included in the bundled payment program. This subgroup also performed the function of reviewing cases that had an unfavorable outcome in terms of quality or cost to determine if the patient should be excluded from the bundle program. In general, if the outcome was deemed attributable to an avoidable cause on the basis of the care model and best practice, the patient was included. For example, if a complication was determined to have occurred as a result of failure to follow Surgical Care Improvement Project elements or to reconcile medications, the patient would be included in the program. If the Clinical Model Subgroup determined that the outcome was unavoidable or unrelated to the bundle, the patient was considered for exclusion. Our goal was to avoid penalizing the physicians, other providers, and the hospital for outcomes that were out of their control. During the bundle period, there was a single patient who was excluded. She was not compliant with her psychiatric medication regimen prior to surgery and had a prolonged postoperative inpatient stay as a result.

Patient Activation

We modified existing educational materials to address education and engagement regarding early hospital discharge. When appropriate, we discharged patients directly to home with therapy and services instead of transfer to a facility for rehabilitation, using published appropriateness criteria as a guide for physical therapists and physicians. A patient compact was created to make explicit that the patient take responsibility for doing rehabilitation, taking medications, following up with his or her physician, and generally being an active participant in the plan of care. Along with the compact was an education program that was provided both during the preoperative history and physical with the orthopedist and also in a session at the hospital. The education focused on patient issues specific to the total hip replacement procedure and subsequent recovery.

Patient activation through incentives was considered. The Financial Model Subgroup discussed creating financial incentives, such as lower copays for patients in the program (for example, for a home discharge), but because of the small size of the pilot, decided against it because of administrative challenges.

Pilot Results

We included 45 patients who underwent elective total hip replacement during the bundled payment pilot between January and December 2011. Of these patients, almost half (22 [49%]) were male and most (44 [98%]) were white, and the median age was 55 years (Table 1, page 411). Bundle patients were compared to 32 elective total hip replacement patients treated from January 2009 through April 2010 who had very similar demographic characteristics. There was no statistically significant difference between groups in rate of obesity or combined comorbidity score.

Table 1.

Characteristics and Outcomes for Total-Hip-Replacement Patients, Baseline (2010) and Bundle (2011) Periods

| Baseline Period (N = 32) n (%) or Median [IQR] |

Bundle Period (N = 45) n (%) or Median [IQR] |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | |||

| Age | 58.5 [55–62] | 55 [51–60] | .24* |

| Male | 16 (50) | 22 (49) | .92† |

| White | 31 (97) | 44 (98) | .66‡ |

| Principal Diagnosis: 715.35 Osteoarthrosis, localized NOS Pelvis | 23 (72) | 43 (96) | .006‡ |

| Gagne Comorbidity Score | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) | .15* |

| Obese | 5 (16) | 3 (7) | .27‡ |

| Surgeon | |||

| 1 | 13 (41) | 15 (33) | |

| 2 | 13 (41) | 22 (49) | .0011‡ |

| 3 | 6 (19) | 0 (0) | |

| 4 | 0 (0) | 8 (18) | |

| DRG Rate Group | .08‡ | ||

| Baystate Health Employee Group | 10 (31) | 5 (11) | |

| HMO/PPO | 19 (59) | 36 (80) | |

| Select | 3 (9) | 4 (9) | |

| Outcomes | |||

| LOS (Mean SD) | 3.4 (1.6) | 3.0 (0) | .24§ |

| LOS | 3 [2–12] | 3 [3–4] | .24* |

| Discharge to: | |||

| Home, self-care | 2 (6) | 1 (2) | |

| Home health services | 20 (63) | 39 (87) | .032‡ |

| Skilled nursing/rehab | 10 (31) | 5 (11) | |

| Facility Total Payment ($) | 26,412 (25,769–28,184) | 22,567 (22,284–23,029) | .0001* |

| Total Payment, adjusted for DRG change ($) | 22,272 (21,629–24,148) | 22,567 (22,284–23,029) | .43 |

| Payment Breakdown ($) | |||

| Physician Payment | 2,736 (2,680–2,809) | 2,541 (2,489–2,729) | .0011* |

| Hospital Payment | 22,043 (22,008–23,240) | 19,101 (19,101–19,612) | < .0001* |

| Hospital Payment adjusted for DRG change | 18,007 (17,868–19,100) | 19,101 (19,101–19,612) | < .0001* |

| Posthospital Payment | 1,121 (728–3,619) | 704 (575–840) | .0018* |

IQR, interquartile range; NOS, not otherwise specified; DRG, diagnosis-related group; HMO, health maintenance organization; PPO, preferred provider organization; LOS, length of stay; SD, standard deviation; rehab, rehabilitation.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Chi-square test.

Fisher’s exact test.

t-test.

Compared to patients treated in the baseline period, those treated during the bundled payment pilot were more likely to be discharged directly to home rather than to a rehabilitation facility (63% versus 87% discharged home, p = .03). Mean LOS decreased from 3.4 days in the baseline period to 3.0 days during the pilot (p = .24). There was an improvement in adherence to a composite of the Surgical Care Improvement Project process measures (95% to 99%; p = .05, Table 2, page 412). In the baseline and bundle periods, there were no readmissions at 30 days, no deaths, and no identified episodes of surgical site infection, urinary tract infection, complications of anesthesia, or postoperative sepsis.

Table 2.

Surgical Care Improvement Project Scores for Total-Hip-Replacement Patients, Baseline (2010) and Bundle (2011) Periods

| Baseline Period (2010; N = 32) | Bundle Period (2011; N = 45) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Measure | n (%) | n (%) | P Value |

| Appropriate antibiotic selection | 29 (91) | 45 (100) | .068 |

| Antibiotics discontinued within 24 hours | 30 (94) | 45 (100) | .170 |

| Appropriate hair removal | 32 (100) | 45 (100) | -- |

| Beta blocker continued through perioperative period | 4/4 (100) | 7/8 (88) | 1.000 |

| Appropriate Care “All or none” | 27 (84) | 44 (98) | .076 |

| Composite (mean, SE) measure numerator/ measure denominator | .95 (0.02) | .99 (0.01) | .052* |

SE, standard error.

p-value from t-test; all others from Fisher’s Exact Test.

The median total cost per case decreased from $26,412 during the baseline period to $22,567 during the bundle period (p = .0001). After adjustment for changes in DRG weight that occurred January 1, 2011, for all Health New England patients, however, the adjusted median cost per case did not show a significant change, as it was $22,272 during the baseline period and $22,567 during the bundle pilot (p = .43). A decrease in the median total hospital payment of $3,000 was primarily explained by the decrease in the payment related to changes in the DRG—an adjustment that caused hospital payments to appear as if they had increased by $1,000 There were statistically significant lower payments to the physicians ($2,736 in the baseline period versus $2,541 in the postbundle period, p = .001). When we analyzed postacute care costs, we also observed a significant decrease (baseline period, median $1,121 versus postbundle, $704, p = .002).

Discussion

We have described the development, implementation, and early-phase results of a bundled payment program for total hip replacement that was associated with similar total costs, lower posthospital costs, shorter LOS, and similar or higher quality of care in the hospital. The program was carried out within the context of an integrated health care delivery system with a hospital, a provider-sponsored health plan, a visiting nurse association, and an independent group of orthopedic surgeons. Lower posthospital costs realized for the bundle program were derived almost exclusively from decreased utilization of skilled nursing facilities.

In contrast to a previous report on bundled payments, which included employed physicians, this program had the participation of an independent, nonemployed physician group.3 An important factor in the implementation of the bundle program was that the physician group had an established track record of programmatic development with the hospital, including best-practice protocols and team-based care. Our bundle program was designed to be simple, both in terms of the elements of the bundle and the mechanism by which savings were distributed, and selective, in that it included a portion of posthospital costs. The providers were deemed appropriate for receipt of a portion of savings as long as performance on quality measures was maintained at or above baseline levels. The structure of the program enabled us to make continuous efforts to include physicians, physical therapists, case managers, and administrators in the bundle design and implementation to ensure buy-in and commitment to the success of the program.

Our experience should be interpreted in the context of prior work. The findings of a recent report tempered enthusiasm for bundled payments in the commercial sector. The study described a multipayer, multiprovider initiative in California that provided bundled payment for orthopedic procedures for patients younger than 65 years of age.17,18 Providers in this pilot program were at full risk for orthopedic bundles, including a 90-day warranty period. However, the initiative failed to enroll a sufficient number of patients for evaluators to assess quality and cost of care under bundled payments, with just 35 patients in participating hospitals and 111 patients in ambulatory surgery centers. This occurred because the pilot program encountered a number of barriers; for example, it attempted to use a retrospective payment reconciled against the target bundle rate but encountered substantial administrative burden related to the manual administration of claims. There were also significant regulatory delays to contract approval. Notably, the orthopedic bundles in the pilot program did not include posthospital services (except physical therapy); it also had no risk-adjustment or stop-loss features. The reported difficulty in implementing bundled payment echoed the earlier findings of the evaluation of the Prometheus Payment program.4,5

We found that establishing the services and parameters regarding the bundle definition (Sidebar 1) was a key component of the success of the program. In addition, similar to the Prometheus pilot, we found that the committee structure (using both a clinical and finance team) and engaging stakeholders early on were important contributors to program implementation. 4,5,17,18 It should also be noted, however, that it remains unclear whether our pilot demonstrated significant overall cost savings. This is because the initiation of the pilot coincided with a change in the DRG weighting, which resulted in an average reduction in payment of approximately $4,000 per patient. For example, real cost savings were observed, as in the decreases in payments to physicians and postacute care costs. There were also actual decreases in the payment to the hospital (from $22,043 to $19,101). However, because there was a concomitant change in the DRG, it was nearly impossible to know what proportion, if any, in the change in payments to the hospital was due to the bundle program. In an attempt to determine whether the bundle program had an impact, we adjusted the payments to reflect the DRG weighting. The result was that although we observed decreases in physician payments and postacute care, the apparent “increase” in the cost of hospital care negated these changes, resulting in a nonsignificant change in total costs. Our difficulty in describing the change in the total cost is emblematic of the difficulty that evaluation of these programs faces, as they must be evaluated in light of such changes in payments, temporal trends, and the influence of other external variables. However, we were able to demonstrate a change in clinical practice, as reflected in a clinically and statistically significant reduction in discharge to skilled nursing facilities and a corresponding decrease in postacute care costs.

Although the findings are encouraging, they must be viewed in light of a number of limitations. We acknowledge that this work represents the experience of a single institution, so that findings may not be generalizable, in part because the institution is a highly integrated delivery system with a subsidiary health plan. Also, this bundle program was limited to a single group of three orthopedic surgeons and did not include other physician specialties, used a retrospective reconciliation approach, and entailed no financial risk for the participating physicians. Organizations with a lesser degree of integration may encounter less favorable conditions for program implementation. Also, while there were no apparent differences in patient characteristics at baseline and during the bundle (including comorbidities and obesity rates), there is still the possibility of bias in patient selection. Patients during the bundle therefore might have been different than patients in the baseline period.

Perhaps our most important “lesson learned” was that a critical factor in the success of the program was the commitment of the physician group, the willingness of the health plan representatives to provide financial and clinical input, and the dedication of hospital and Visiting Nurse Association leaders throughout the development and implementation phases.

Administering the program was a serious undertaking relying on the perseverance of all the involved parties. This administrative burden would have existed regardless of the payment mechanism or the bundle elements because payment reforms such as these will require significant administrative time and effort. In the future, similar programs, including those being developed as part of the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative under the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation,11 must develop similar stakeholder engagement strategies and work to develop operational efficiencies in order to be scalable to a large number of patient groups. The tasks of establishing pricing and clinical models, tracking performance, and distributing payments will require substantial administrative effort for bundled payment programs to begin to realize their potential as a cornerstone of health care reform.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Lagu is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01HL114745. Dr. Lagu has received consulting fees from The Island Peer Review Organization, under contract to CMS, for her work on development of episodes of care for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid payment purposes. Dr. Whitcomb reports stock options with Remedy Partners. The authors thank Katherine Dempsey and Anu Joshi for their help with formatting and proofreading an earlier version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

J.M., Janice Mayforth.

Contributor Information

Winthrop F. Whitcomb, Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, Massachusetts, and Chief Medical Officer, Remedy Partners, Darien, Connecticut.

Tara Lagu, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, and Research Scientist, Center for Quality of Care Research, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Massachusetts.

Robert J. Krushell, Clinical Instructor of Surgery, Tufts University School of Medicine, and Medical Director, Hip and Knee Replacement Program, Baystate Medical Center.

Andrew P. Lehman, Orthopedic Surgeon, New England Orthopedic Surgeons, Springfield, and Assistant Director, Hip and Knee Replacement Program, Baystate Medical Center.

Jordan Greenbaum, Orthopedic Surgeon, New England Orthopedic Surgeons, Springfield.

Joan McGirr, Total Joint Replacement Coordinator, Baystate Medical Center.

Penelope S. Pekow, Senior Biostatistician Consultant, Center for Quality of Care Research, Baystate Medical Center, and Research Assistant Professor, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Stephanie Calcasola, Director, Quality and Medical Management, Baystate Medical Center.

Evan Benjamin, Professor of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, and Senior Vice President, Healthcare Quality and Population Health, Baystate Health, Springfield.

Janice Mayforth, Director, Clinical Financial Planning and Decision Support, Baystate Health.

Peter K. Lindenauer, Associate Professor of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine; Director, Center for Quality of Care Research, Baystate Medical Center; and Member, The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety’s Editorial Advisory Board.

References

- 1.Hussey PS, et al. Episode-based performance measurement and payment: Making it a reality. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(5):1406–1417. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mechanic RE, Altman SH. Payment reform options: Episode payment is a good place to start. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(2):w262–271. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.w262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casale AS, et al. “ProvenCareSM”: A provider-driven pay-for-performance program for acute episodic cardiac surgical care. Ann Surg. 2007;246(4):613–621. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318155a996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hussey PS, Ridgely MS, Rosenthal MB. The Prometheus bundled payment experiment: Slow start shows problems in implementing new payment models. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(11):2116–2124. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Brantes F, Rosenthal MB, Painter M. Building a bridge from fragmentation to accountability—The Prometheus Payment model. N Engl J Med. 2009 Sep 10;361(11):1033–1036. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0906121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed Jul 28, 2014];Medicare Acute Care Episode (ACE) Demonstration. http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/ACE/

- 7.Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Executive Office for Administration and Finance. [Accessed Jul 28, 2015];Payment Reform and What Could Change in Health Care Delivery. 2011 http://www.mass.gov/anf/employee-insurance-and-retirement-benefits/oversight-agencies/gic/payment-reform.html.

- 8.Emanuel EJ. The Arkansas innovation. [Accessed Jul 28, 2015];New York Times, Opinionator blog. 2012 Sep 5; http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/05/the-arkansas-innovation/

- 9.US Government Publishing Office. H.R. 3590 (111th): Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Public Law 111–148. [Accessed Jul 28, 2015];2010 Mar 23; http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf.

- 10.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed Jul 28, 2015];Fact Sheets: Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative. 2011 Aug 23; http://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-Sheets/2011-Fact-Sheets-Items/2011-08-23.html.

- 11.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed Jul 28, 2015];Fact Sheets: Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative Fact Sheet. 2014 Jul 31; http://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2014-Fact-sheets-items/2014-07-31.html.

- 12.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed Jul 28, 2015];Fact Sheets: Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement. 2015 Jul 9; https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-07-09.html.

- 13.Then Joint Commission. [Accessed Jul 28, 2015];Surgical Care Improvement Project. 2014 Oct 16; http://www.jointcommission.org/surgical_care_improvement_project/

- 14.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed Jul 28, 2015];Patient Safety Indicators Overview. http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/modules/psi_overview.aspx.

- 15.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed Jul 28, 2015];Hospital-Acquired Conditions. (Updated: Aug 28, 2014.) http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalAcqCond/Hospital-Acquired_Conditions.html.

- 16.McKesson. InterQual® Level of Care Criteria. Newton, MA: McKesson Corporation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Integrated Healthcare Association. Williams T, Robinson J, editors. [Accessed Jul 28, 2015];Bundled Episode-of-Care Payment for Orthopedic Surgery: The Integrated Healthcare Association Initiative. 2013 Sep; Issue Brief No. 9. http://www.iha.org/pdfs_documents/bundled_payment/Bundled-Payment-Orthopedics-Issue-Brief-September-2013.pdf.

- 18.Ridgely MS, et al. Bundled payment fails to gain a foothold in California: The experience of the IHA bundled payment demonstration. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(8):1345–1352. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]