Abstract

Obesity and insulin resistance are associated with increased risk of cancer and cancer mortality. However, it is currently unknown whether they contribute to the development of cancer cachexia, a syndrome that contributes significantly to morbidity and mortality in individuals with cancer. The present experiment addresses the question of whether pre-existing obesity and insulin resistance alter tumor growth and cancer cachexia symptoms in Yoshida sarcoma bearing male rats. Obesity and insulin resistance were induced through five weeks of high-fat (HF) diet feeding and insulin resistance was confirmed by intraperitoneal glucose tolerance testing. Chow-fed animals were utilized as a control group. Following the establishment of insulin resistance, HF- and chow-fed animals were implanted with fragments of the Yoshida sarcoma or received a sham surgery. Tumor growth rate was greater in HF-fed animals, resulting in larger tumors. In addition, cancer cachexia symptoms developed in HF-fed animals but not chow-fed animals during the 18 day experiment. These results support a stimulatory effect of obesity and insulin resistance on tumor growth and cancer cachexia development in Yoshida sarcoma bearing rats. Future research should investigate the relationship between obesity, insulin resistance, and cancer cachexia in human subjects.

Keywords: High-fat diet, obesity, insulin resistance, cancer cachexia, tumor growth

Introduction

The presence of obesity in modern society has reached epidemic proportions (1). The burden of obesity includes an increased risk for developing a number of additional chronic diseases, including Type II diabetes mellitus and cancer (2). Independent of weight status, Type II diabetes and insulin resistance are also associated with an increased risk of developing multiple types of cancer, including cancers of the liver, pancreas, endometrium, colon/rectum, and breast (3–5), as well as cancer mortality (6). While the mechanisms linking obesity, insulin resistance, and cancer mortality are not yet fully elucidated, cancer cachexia may be involved.

Cancer cachexia is a devastating syndrome present in many individuals with cancer. Characterized by weight loss, loss of appetite, and wasting of skeletal muscle and adipose tissues, cancer cachexia contributes significantly to morbidity and mortality in this population. Individuals who experience cachexia have reduced survival time, diminished psychological and physical health, as well as more negative side effects and a decreased therapeutic response during chemotherapy (7–14). Overall, the influence of cachexia on individuals with cancer is great – an estimated one third of cancer deaths may be attributable to cachexia, rather than the tumor burden itself (15).

It is currently unknown whether the presence of obesity and insulin resistance prior to cancer development influences the subsequent development of cancer cachexia. The aim of the present experiment was to determine the effects of diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance on tumor growth and the development of cancer cachexia in rats bearing the Yoshida sarcoma. This is a well-established model of cancer cachexia, which closely resembles the human condition (16). High-fat diet feeding, which results in a well-established clinical model of obesity and Type II diabetes (17), was utilized. Cachexia was considered present when body weight gain (minus tumor weight), caloric intake, lean mass, and fat mass were significantly lower in tumor-bearing animals, as compared to same-diet controls.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

Thirty-eight male Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were individually housed in hanging wire mesh cages in a temperature and humidity controlled room, with a 12:12h light:dark cycle (lights on at 04:00). Throughout the experiment, all rats received ad libitum access to tap water and the assigned diet. All procedures were approved by the Purdue University Animal Care and Use Committee.

The experiment proceeded in two phases. In Phase I, rats were weight matched and divided into two groups, which differed in experimental diet. One group (n = 19, chow) received ad libitum access to a semi-purified chow diet (AIN-76A, Dyets, Inc., Bethlehem, PA). The other group (n = 19, HF) received ad libitum access to a high-fat, high-carbohydrate diet (D12492, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ). Animals were weighed three times per week during this phase of the experiment. After 4–5 weeks, chow and HF rats underwent to an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test. The criteria for insulin resistance were 1) elevated basal glucose levels, 2) elevated glucose area under the curve (AUC), and 3) elevated basal insulin levels in HF rats, as compared to chow-fed animals.

Following the establishment of insulin resistance, Phase II of the experiment began. Each diet group was further divided into two weight-matched groups (n = 9–10 per group), which differed in tumor status. The control group received a sham surgery. The tumor-bearing (TB) group was subcutaneously implanted with the Yoshida sarcoma. All rats continued to receive the previously assigned diet. Total weight (rat plus tumor weight) and food intake, minus food spillage, were measured daily. Daily water intake was also measured.

Intraperitoneal Glucose Tolerance Testing (IPGTT)

In preparation for IPGTT, food was removed 1h after lights out on the day prior to testing. On test day, rats were weighed to determine post-deprivation body weight. A 200 μL blood sample was collected via tail nick for measurement of baseline blood glucose and plasma insulin levels. Each rat was then received an intraperitoneal injected of glucose at a dose of 1.5g/kg body weight (D-glucose, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Additional blood samples were collected 15, 30, 45, 60, and 120 minutes after glucose injection. Blood glucose levels were measured using the Precision Xtra Glucose Monitoring System (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott, IL). The remaining samples from each time point were then centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C. Plasma was removed and stored at −80°C for analysis of plasma insulin levels.

Tumors and Tumor Implantation

Yoshida sarcoma ascites tumor cells were purchased from the Development Therapeutics Program at the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD). A detailed description of the tumor implantation procedure has been published previously (16). Briefly, donor animals were used to perpetuate the tumor line in the laboratory. After the donor rat received an overdose of sodium pentobarbital, the tumor tissue was quickly dissected, divided into fragments, and placed on ice. The animal receiving the tumor was anesthetized under isoflurane anesthesia, and a tumor fragment (approximately 6 mm3) was subcutaneously implanted. All TB animals received tumor tissue from the same donor animal. Sham surgeries were performed in control animals. Surgeries were performed on experimental Day 0.

Tumor volume was determined through measurement of tumor size by external digital caliper, with the longest longitudinal diameter (length, L), greatest transverse diameter (width, W), and the great vertical diameter (height, H) recorded daily. Tumor volume was calculated using a standard ellipsoid formula [V = π/6 × (L)(W)(H)] (18). A linear regression equation has previously been generated by comparing final tumor volume and tumor weight in all experimental animals generated to date in the laboratory (y = 0.998× + 2.4173) (16). This equation was utilized to calculate the approximate weight of each TB rat’s tumor, based on measured tumor volume, during the experiment.

Measurement of Body Composition

Body composition was assessed on Days 0, 7, and 14. Fat mass (% body fat) was analyzed in conscious rats using the EchoMRI system (Echo Medical Systems, Houston, TX). Hind leg diameter was utilized as a measure of skeletal muscle mass. The contralateral hind leg, relative to the tumor, was extended and the diameter of the upper leg was measured via external digital caliper and recorded.

Sacrifice and Terminal Measures

Rats were sacrificed on Day 18 under ether inhalation anesthesia followed by rapid decapitation approximately 4 hours prior to the start of the dark cycle. Trunk blood was collected for analysis of non-fasting blood glucose and plasma insulin levels. Blood glucose levels were measured as during IPGTT. The remaining blood samples were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C, and plasma was removed and stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis of insulin levels.

The epididymal fat pads were removed from each animal weighed, as a measure of terminal fat mass. Additionally, hind leg diameter, both contralateral and ipsilateral to the tumor, was measured, as a measure of terminal skeletal muscle mass. In TB rats, the tumor was also removed and weighed. Small samples of epididymal fat and quadriceps muscle were collected and placed in RNAlater for analysis of mRNA expression by QPCR.

Radioimmunoassay (RIA)

Plasma insulin levels were determined using a commercial Rat Insulin RIA kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA), with upper and lower detection limits of 0.1 ng/mL and 10 ng/mL, respectively. All samples were run in duplicate and per manufacturer’s instructions. Unknown concentrations of insulin were calculated based on a standard curve generated for each kit.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (QPCR)

Expression of atrogin-1 and hormone sensitive lipase (HSL) was measured via QPCR to determine the effects of diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance on two molecular markers of cancer cachexia. Atrogin-1 is an important enzyme the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, which is responsible for skeletal muscle degradation during cancer cachexia, while HSL is an enzyme that may be important in the degradation of adipose tissue (19, 20).

RNA was isolated from tissue samples for determination of mRNA expression. Tissue samples (100mg) were homogenized in 2 mL of Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized from 0.5–3μg of RNA using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and diluted in nuclease-free water for storage at −80°C. Primer sequences are listed in Table 1. QPCR was performed in duplicate using a BioRad iCycler and Maxima Sybr Green solution (Thermo Scientific, Barrington, IL) with two-step (L32 and atrogin-1) or three-step (β-actin and HSL) amplification for 40 cycles. L32 was amplified from each sample for use as an endogenous control for atrogin-1 in quadriceps muscle samples, while β-actin served as an endogenous control for HSL in epididymal fat samples. The method of Pfaffl was used to determine expression of the genes of interest (21). Expression was calculated based on normalization to the housekeeping gene (L32 or β-actin), relative to the efficiency of the housekeeping and interest genes in the target tissue.

Table 1.

Primers sequences for QPCR analysis of mRNA expression.

| Gene | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|

| L32 | Forward: 5′-CAG ACG CAC CAT CGA AGT TA-3′ Reverse: 5′-AGC CAC AAA GGA CGT GTT TC-3′ |

| β-actin | Forward: 5′-CGT GGG CCG CCC TAG GCA CCA-3′ Reverse: 5′-CTC TTT GAT GTC ACG CAC GAT TTC-3′ |

| Atrogin-1 | Forward: 5′-GTC CAG AGA GTC GGC AAG TC-3′ Reverse: 5′-GTC GGT GAT CGT GAG ACC TT-3′ |

| Hormone Sensitive Lipase (HSL) | Forward: 5′-GAA TAT CAC GGA GAT CGA GG-3′ Reverse: 5′-CCG AAG GGA CAC GGT GAT GC-3′ |

Statistical Analyses

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Software.

During Phase I of the experiment, body weight in HF- and chow-fed rats was analyzed by two-way ANOVA, with planned Bonferroni comparisons. Average daily caloric intake, as well as body fat and hind leg diameter was analyzed by Student’s t-test. Basal blood glucose and plasma insulin levels, as well as glucose AUC from the IPGTT were analyzed by Student’s t-test.

During Phase II, the tumor growth curve for each diet group was analyzed for fit in an exponential equation. Tumor volume was analyzed by two-way ANOVA, with planned Bonferroni comparisons. Terminal tumor weight was analyzed via Student’s t-test.

Change in total weight, change in body weight (total weight, minus calculated tumor weight), mean daily caloric intake, and mean daily water intake were analyzed via two-way ANOVA. Body composition (percent body fat or hind leg diameter) was analyzed by two-way ANOVA on Days 7 and 14. Epididymal fat pad weight, as well as contralateral and ipsilateral hind leg diameter, was measured on the day of sacrifice and analyzed by two-way ANOVA. Planned Bonferroni comparisons were performed as appropriate.

QPCR data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA, with separate analyses for each gene of interest in each tissue and planned Bonferroni comparisons. Data are expressed as a percent of expression for each gene, relative to the expression of that gene in the chow-fed control group.

Results

Phase I: Establishment of Diet-induced Obesity and Insulin Resistance

Table 2 summarizes evidence of obesity and insulin resistance induced by high-fat diet feeding. HF rats weighed significantly more than chow-fed rats during Phase I. HF rats weighed significantly more than chow rats starting on Day 21, and this effect continued to the end of the initial feeding period (Day 21–30, p < 0.05 for all). HF-fed rats also consumed significantly more calories per day on average, as compared to chow-fed animals (p < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Obesity and insulin resistance induced by five weeks of high-fat diet consumption.

| Chow | HF | |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 327.8 ± 6.3 | 347.5 ± 4.5* |

| Mean daily caloric intake (kcal) | 74.2 ± 0.5 | 81.6 ± 0.6* |

| Body fat (% body weight) | 10.4 ± 0.6 | 14.2 ± 0.6* |

| Hind leg diameter (mm) | 13.1 ± 0.1 | 13.4 ± 0.1 |

| Basal blood glucose (mg/dL) | 89.2 ± 2.6 | 101.1 ± 1.9* |

| Basal plasma insulin (ng/mL) | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 0.72 ± 0.07* |

| Glucose AUC | 494.3 ± 11.7 | 554.9 ± 15.4* |

p < 0.05, as compared to chow.

Body composition was measured after 5 weeks of HF diet feeding. Analysis of body adiposity revealed a significantly higher percentage of body fat in HF-fed rats, as compared to chow-fed rats (p < 0.0001). Contralateral hind leg diameter was not significantly different in HF rats, as compared to chow.

IPGTT was performed after 4–5 weeks of diet feeding. Fasting blood glucose and plasma insulin levels were significantly higher in HF-fed animals, as compared to chow (p < 0.001, and p < 0.01, respectively). HF rats had a significantly greater glucose AUC than chow rats (t (35) = 3.103, p < 0.01). For the purposes of this experiment, elevated basal glucose and insulin levels, and increased glucose AUC were sufficient to determine that insulin resistance was present in HF-fed animals (Table 2).

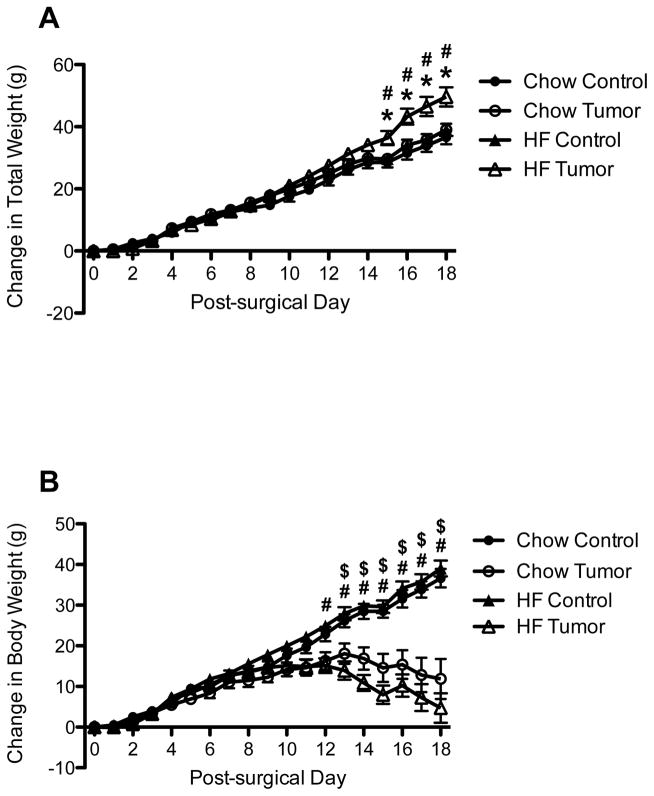

Phase II: Change in Total Weight and Body Weight

Following tumor implantation, analysis of the change in total weight by two-way ANOVA revealed a significantly greater change in body weight in HF-fed TB rats, as compared to both HF-fed control and chow-fed TB rats on Days 15–18 (p < 0.05 for all) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Change in total weight (A) and body weight (B) in control and tumor-bearing (TB) rats. *p < 0.05, as compared to chow-fed TB; # p < 0.05, as compared to HF-fed controls; $ p < 0.05, as compared to chow-fed controls

When calculated tumor weight was subtracted from total weight change, yielding change in body weight data, analysis by two-way ANOVA that in both diet groups, TB animal gain significantly less weight then their same diet controls (Chow: p < 0.05, Day 13–18; HF: p < 0.05 Day 12–18) (Figure 1B). No significant differences were observed between TB rats fed chow and HF, or between control animals fed chow or HF.

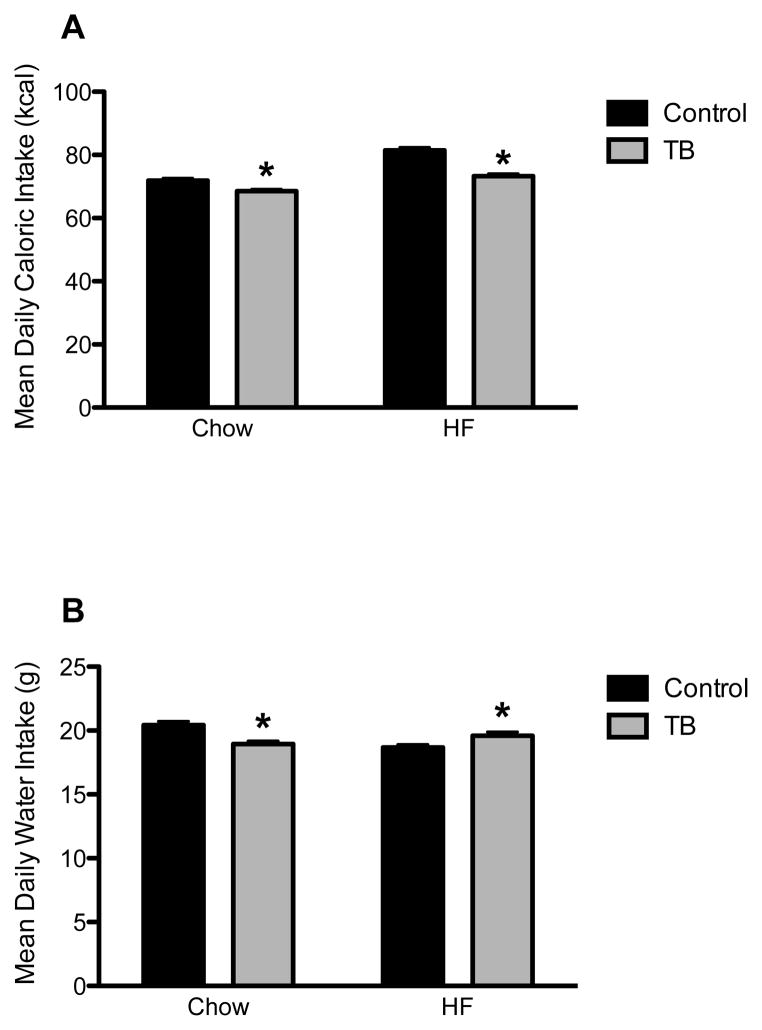

Phase II: Caloric Intake and Water Intake

Caloric intake was measured daily and corrected for food spillage. Caloric intake was greater in HF rats, as compared to CH rats. In both diet groups, tumor-bearing rats consumed significantly fewer calories, as compared to control rats (p < 0.05 for each), though this difference was greater in HF rats than chow rats (Chow: 3.36 kcal vs. HF: 8.14 kcal) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Mean daily caloric intake (A) and water intake (B) in control and tumor-bearing (TB) rats. *p < 0.05, as compared to same diet controls

Water intake was measured as a method of assessing hydration status. While chow-fed TB rats consumed significantly less water than their same diet controls (p < 0.001), HF-fed tumor-bearing rats consumed significantly more water than their controls (p < 0.05) (Figure 2B).

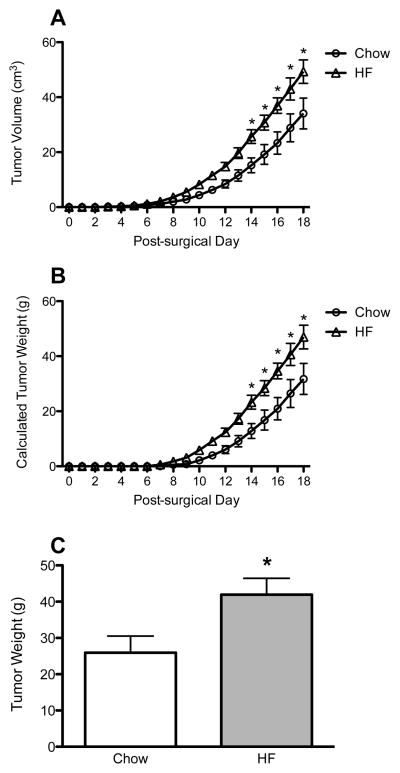

Phase II: Tumor Volume and Final Tumor Weight

Tumor volume was measured daily throughout the experiment. Tumors in both diet groups followed an exponential growth pattern, with a doubling time of approximately 3.17 days in chow rats and 2.87 days in HF rats. HF-fed rats experienced greater tumor growth, with a significantly greater tumor volume, as compared to chow-fed rats, beginning at Day 14 and continuing to the end of the experiment (Day 14–18, p < 0.05 for all) (Figure 3A). Approximate tumor weight was calculated for each rat based on measured tumor volume. Calculated tumor weight was found to follow the same significance pattern as tumor volume, with HF rats having significantly heavier tumors on Days 14–18 (p < 0.05 for all) (Figure 3B). On the day of sacrifice, HF-fed rats also had heavier tumors, as compared to chow-fed rats (p < 0.05) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Tumor volume (A) and tumor weight (B) in chow- and HF-fed rats over time, and final tumor weight (C). *p < 0.05, as compared to same diet controls.

Phase II: Body Composition

Body composition was analyzed on Day 7 and Day 14 following tumor implantation. On both days, analysis of body fat levels indicated that HF-fed rats had a significantly higher percentage of body fat, as compared to chow-fed. However, no differences were observed between control and tumor-bearing animals in either diet group (data not shown). On Day 7, HF-fed rats had significantly greater hind leg diameter, as compared to chow-fed rats (p < 0.05). No differences were observed between control and tumor-bearing animals in either diet group. On Day 14, two-way ANOVA revealed no significant differences between groups (data not shown).

Additional measures of body composition were taken at the time of sacrifice on Day 18 (Table 3). While HF-fed rats exhibited significantly greater epididymal fat pad weights, as compared to chow-fed rats, TB HF rats had significantly less epididymal fat than the HF-fed controls (p < 0.05). This difference between control and TB rats was not present in the chow-fed group. In addition, ipsilateral and contralateral hind leg diameters were smaller in TB animals, as compared to controls (p < 0.05), and this effect did not differ based on diet.

Table 3.

Terminal body composition and blood measurements.

| Chow | HF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | TB | Control | TB | |

| Epididymal Fat (g) | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 8.0 ± 0.6 | 6.0 ± 0.5 ** |

| Hind leg diameter | ||||

| Contralateral (mm) | 13.0 ± 0.2 | 12.6 ± 0.2 * | 13.3 ± 0.2 | 12.5 ± 0.2 ** |

| Ipsilateral (mm) | 13.1 ± 0.2 | 12.7 ± 0.2 * | 13.4 ± 0.2 | 12.3 ± 0.2 ** |

| Blood Glucose (mg/dL) | 157 ± 9.8 | 160 ± 8.5 | 147 ± 2.7 | 139 ± 6.6 |

| Plasma Insulin (ng/mL) | 1.37 ± 0.32 | 1.40 ± 0.41 | 2.41 ± 0.34 | 1.04 ± 0.27 ** |

p < 0.05, compared to chow control;

p < 0.05, compared to HF control.

Phase II: Terminal Blood Glucose and Plasma Insulin

Analysis of terminal, non-fasting blood glucose levels revealed that HF-fed rats generally exhibited lower glucose levels than did chow-fed animals. No effect of tumor status was observed. Analysis of plasma insulin levels revealed an interesting pattern of results. While no differences were observed between tumor-bearing and control chow-fed rats, TB rats fed the HF diet had significantly lower insulin levels than HF-fed control rats (p < 0.01) (Table 3).

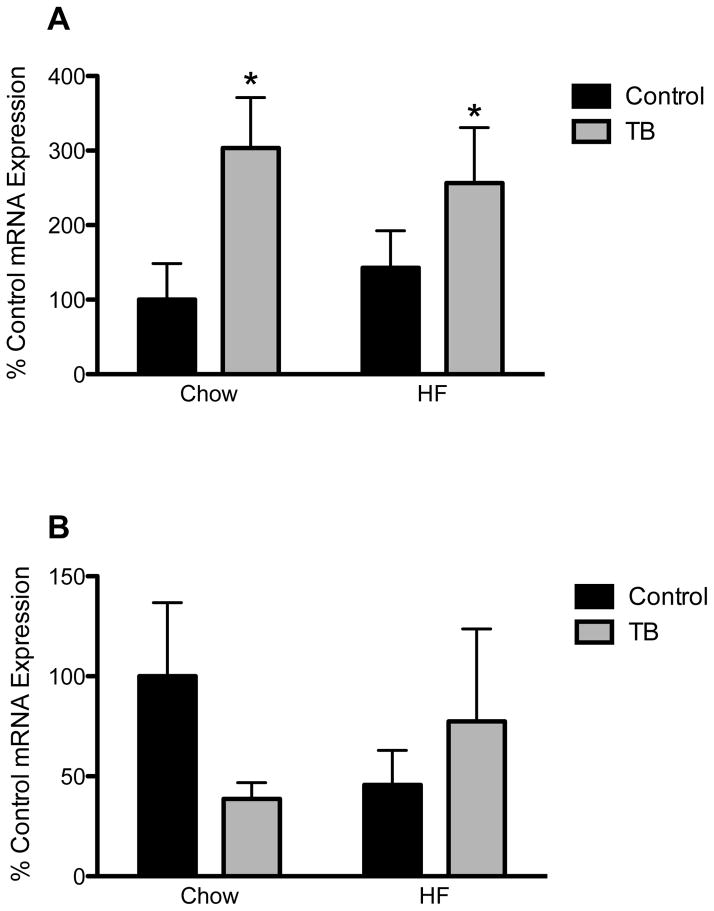

Phase II: QPCR Analysis

Atrogin-1 mRNA expression in quadriceps muscle samples was increased in tumor-bearing groups of both diets, as compared to same diet controls (significant main effect of tumor status, p < 0.05) (Figure 4A). No differences in HSL expression in epididymal fat samples were observed (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Atrogin-1 (A) and Hormone Sensitive Lipase (HSL) (B) mRNA expression in quadriceps muscle and epididymal fat samples, respectively. *p < 0.05, as compared to same diet controls.

Discussion

High-fat diet feeding is an important tool for examining the effects of diet and metabolic function in various human-like disease states. In the present experiment, high-fat feeding produced a number of symptoms characteristic of human obesity and Type II diabetes, including increased body weight and body adiposity, increased caloric intake, and signs of glucose intolerance and insulin resistance. This model was utilized as a starting point to examine the effects of pre-existing obesity and insulin resistance on subsequent development of cancer cachexia.

HF-fed TB rats gained less weight, consumed fewer calories, and exhibited lower levels of body fat and skeletal muscle mass, as compared to HF-fed controls. Elevated atrogin-1 mRNA expression in HF tumor-bearing rats indicates the presence of proteolysis via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, which is characteristic of muscle wasting during cancer cachexia. HF-fed tumor bearing animals also exhibited lower insulin levels than same diet controls. These results indicate that HF-fed tumor-bearing rats developed cancer cachexia within 18 days of tumor implantation. Chow-fed TB animals experienced some of the same symptoms, including decreased body weight gain, caloric intake, hind leg diameter, and atrogin-1 mRNA expression. However, chow-fed animals did not exhibit the characteristic decrease in fat mass or plasma insulin levels associated with cancer cachexia, indicating that cachexia did not develop fully during the 18 day time frame. These results indicate a specific effect of obesity and insulin resistance on the development of cachexia in tumor-bearing animals.

HF-fed TB rats had larger tumors, as compared to chow-fed TB rats. In addition, the doubling time was less in HF-fed animals, indicating a faster rate of tumor growth in this group. Previous research has demonstrated a stimulatory effect of obesity and insulin resistance on tumor growth in male rats bearing the Walker 256 carcinoma, with obese animals experiencing greater tumor weight and volume than non-obese animals (22). Fonesca and colleagues also observed a similar pattern of plasma insulin levels among tumor-bearing animals, with obese animals exhibiting lower plasma insulin levels than non-obese animals (17). However, this is the first experiment to demonstrate this relationship based on diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance, which more closely models the conditions of human obesity and metabolic syndrome. Future research should continue to investigate the influence of obesity and insulin resistance on cancer cachexia development utilizing this model.

It is unknown whether the present effects on the development of cachexia were produced through direct stimulation of cachexia-related molecular pathways or through its indirect effects, such as an accelerated rate of tumor growth. While tumor burden is not significantly related to the presence or degree of cachexia in human subjects (23), previous research in animal models suggests that the tumor burden plays a significant role in cachexia development (24). However, these findings are not universal (25). Further experimentation are necessary to determine the mechanism or mechanisms through which obesity and insulin resistance aid in the development of cancer cachexia. Additional research in tumor models that do not normally produce cachexia could yield important information regarding the ability of diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance to aid in cachexia development.

The present experiment utilized a valid model of diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance to examine the effects of pre-existing insulin resistance on subsequent cachexia development. Additional experiments are necessary to disentangle the individual contributions of obesity and insulin resistance. Epidemiological evidence suggests that insulin resistance and Type II diabetes mellitus increase the risk of developing certain types of cancer, including cancers of the liver, pancreas, endometrium, colon/rectum, and breast (3–5). This effect is observed even when weight status (normal weight, overweight, obese) is controlled. Hyperinsulinemia has also been positively associated with risk of colon, breast, and endometrial cancers (3). While there do appear to be independent effects of insulin resistance and glucose intolerance on cancer and cancer mortality, more research is still necessary.

In the present experiment, high-fat diet feeding resulted in obesity and insulin resistance in male rats. Upon implantation of the Yoshida sarcoma, these animals developed larger tumors and developed cachexia symptoms more quickly that has previously been observed in chow-fed animals. Given the similarities between this diet model and the obesity-diabetes syndrome observed in many individuals in current society, these results may have important implications for the development of cachexia in obese and/or insulin resistant individuals. Further research is necessary to determine the extent to which these factors may act in human cancer cachexia development. Such research could have important implications for determining cancer cachexia risk in clinical populations and for the treatment and prevention of cachexia in obese, insulin resistant individuals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Sara Hargrave, Meredith Cobb, and Melissa McCurley (for technical assistance), and Dr. Terry Powley, Dr. Terry Davidson, and Dr. Jim Fleet (for editorial comments and suggestions). This work was supported by National Institutes of Health DK078654 (KPK) and by the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute R25CA128770 (D. Teegarden) Cancer Prevention Internship Program administered by the Oncological Sciences Center and the Discovery Learning Research Center at Purdue University (MAH).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303:235–342. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malnick SD, Knobler H. The medical complications of obesity. Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 2006;99:15. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, et al. Diabetes and cancer: A consensus report. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clincians. 2010;60:15. doi: 10.3322/caac.20078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsugane S, Inoue M. Insulin resistance and cancer: Epidemiological evidence. Cancer Science. 2010;101:7. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duggan C, Irwin ML, Xiao L, et al. Associations of insulin resistance and adiponectin with mortality in women with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:1–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parekh N, Lin Y, Hayes RB, Albu JB, Lu-Yao GL. Longitudinal associations of blood markers of insulin and glucose metabolism and cancer mortality in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Cancer Causes and Control. 2010;21:12. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9492-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fearon KCH, Arends J, Baracos VE. Understanding the mechanisms and treatment options in cancer cachexia. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2013;10:90–9. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del Fabbro E, Hui D, Dalal S, Dev R, Noorhuddin Z, Bruera E. Clincal outcomes and contributors to weight loss in a cancer cachexia clinic. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2011;14:1–6. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dewys W, Begg C, Lavin P, et al. Prognostic effect of weight loss prior to chemotherapy in cancer patients. American Journal of Medicine. 1980;69:491–8. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(05)80001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esper DH, Harb WA. The cancer cachexia syndrome: A review of metabolic and clinical manifestations. Nutrition in Clincal Practice. 2005;20:369–76. doi: 10.1177/0115426505020004369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haehling Sv, Anker SD. Cachexia as a major underestimated and unmet medical need: Facts and numbers. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia, and Muscle. 2012;1 doi: 10.1007/s13539-010-0002-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hinsley R, Hughes R. The reflections you get: An exploration of body image and cachexia. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2007;13:8. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2007.13.2.23068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin L, Birdsell LA, Macdonald N, et al. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: Skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:1539–47. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blum D, Omlin A, Baracos VE, et al. Cancer Cachexia: A systematic literature review of items and domains associated with involuntary weight loss in cancer. Critical Reviews in Oncology. 2011;80:114–44. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Eys J. Nutrition and cancer: Physiological interrelationships. Annual Review of Nutiriton. 1985;5:26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.05.070185.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honors MA, Kinzig KP. Characterization of the Yoshida sarcoma: A model of cancer cachexia. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21:2687–94. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1839-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Storlien LH, James DE, Burleigh KM, Chisholm DJ, Kraegen EW. Fat feeding causes widespread in vivo insulin resistance, decreased energy expenditure, and obesity in rats. American Journal Of Physiology: Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1986;251:8. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1986.251.5.E576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomayko MM, Reynolds CP. Determination of subcutaneous tumor size in athymic (nude) mice. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 1989;24:148–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00300234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Attaix D, Combaret EAL, et al. Ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent proteolysis in skeletal muscle. Reproduction, Nutrition, and Development. 1998;38:153–65. doi: 10.1051/rnd:19980202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duncan RE, Ahmadian M, Jaworski K, Sarkadi-Nagy E, Sook Sul H. Regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes. Annual Review of Nutiriton. 2007;27:79–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Research. 2001;29:2002–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fonseca EAI, Oliveira MAd, Lobato NdS, et al. Metformin reduces the stimulatory effect of obesity on in vivo Walker-256 tumor development and increases the area of tumor necrosis. Life Sciences. 2011:846–52. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tisdale MJ. Cachexia in cancer patients. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2002;2:862–71. doi: 10.1038/nrc927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bassukas ID, Maurer-Schultze B. Relationship between tumor growth and cachexia during progressive malignant disease: A new measure of the extent of cachexia, the cachexia index. Anticancer Research. 1991;11:1237–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujimoto-Ouchi K, Tamura S, Mori K, Tanaka T, Ishitsuka H. Establishment and characterization of cachexia-inducing and -non-inducing clones of murine colon 26 carcinoma. International Journal of Cancer. 1995;61:522–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910610416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]