Highlights

-

•

We treat four patients with delayed traumatic diaphragmatic hernia.

-

•

All surgeries were large and delicate clinical management.

-

•

All patients had excellent outcomes.

-

•

If these injuries had been diagnosed early surgical approaches would be less invasive.

Abbreviations: IAP, intra-abdominal pressure; ICU, intensive care unit; VATS, videothoracoscopy

Keywords: Diaphragmatic hernia, Trauma, Intra-abdominal pressure, Videothoracoscopy

Abstract

Introduction

Diaphragmatic rupture is an infrequent complication of trauma, occurring in about 5% of those who suffer a severe closed thoracoabdominal injury and about half of the cases are diagnosed early. High morbidity and mortality from bowel strangulation and other sequelae make prompt surgical intervention mandatory.

Case presentation

Four Brazilian men with a delayed diagnosis of a rare occurrence of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Patient one had diaphragmatic rupture on the right side of thorax and the others three patients on the left thoracic side, all they had to approach by a laparotomy and some approach in the chest, either thoracotomy or VATS. This injuries required surgical repositioning of extensively herniated abdominal viscera and intensive postoperative medical management with a careful control of intra-abdominal pressure.

Discussion

The negative pressure of the thoracic cavity causes a gradually migration of abdominal contents into the chest; this sequestration reduces the abdomen’s ability to maintain the viscera in their normal anatomical position. When the hernia is diagnosed early, the repair is less complicated and requires less invasive surgery. Years after the initial trauma, the diaphragmatic rupture produces dense adhesions between the chest and the abdominal contents.

Conclusions

All cases demonstrated that surgical difficulty increases when diaphragmatic rupture is not diagnosed early. It should be noted that when trauma to the thoraco-abdominal transition area is blunt or penetrating, a thorough evaluation is required to rule out diaphragmatic rupture and a regular follow-up to monitor late development of this comorbidity.

1. Introduction

Diaphragmatic rupture is an infrequent complication of trauma, occurring in about 5% of those who suffer a severe closed thoracoabdominal injury [1,2]. The left side is most commonly involved (80%) [3], and about half of the cases are diagnosed early [4]. High morbidity and mortality from bowel strangulation and other sequelae [2–4] make prompt surgical intervention mandatory [3–6]. With delayed treatment, abdominal viscera can become sequestrated into the chest cavity [7,8]. This situation often requires visceral reduction surgery together with complete muscular relaxation in the immediate postoperative period to control intra-abdominal pressure (IAP). This report describes the delayed diagnosis of four rare occurrences of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. The injuries required surgical repositioning of extensively herniated abdominal viscera and intensive postoperative medical management [9].

2. Case reports

2.1. Patient one

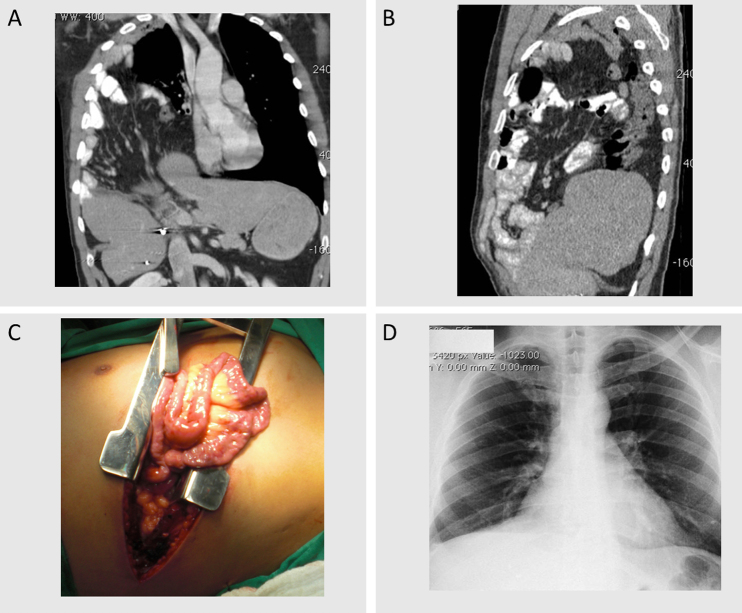

A Brazilian, 37-year-old male presented with the chief complaints of progressive dyspnea and pain in the right thorax. His symptoms exacerbated during and after meals. No breath sounds were detected in the right chest area; however, bowel sounds were audible. Four years ago, he was the victim of a hit-and-run vehicular accident. Chest tomography confirmed a right diaphragmatic hernia (Fig. 1A and B). The surgery was performed with two incisions: an anterolateral right thoracic incision at the seventh intercostal space, and a midline abdominal incision (Fig. 1C). Exploration of the thoracic cavity revealed an 8-inch annular diaphragmatic defect, which allowed passage of the entire colon and greater omentum, as well as the right hepatic lobe, gallbladder, and most of small bowel (10 cm from the ligament of Treitz to cecum). The liver was firmly adherent to the pericardium; therefore, meticulous dissection and excision of a portion of the pericardium was required. The diaphragmatic defect was closed in two layers, using simple sutures (polypropylene 2) with dual mesh (polypropylene/polyethylene) reinforcement at the thoracic interface. Following omentectomy and abdominal closure, the patient was placed in the intensive care unit (ICU) for a full 48 h postoperatively, during which ventilatory assistance and complete muscular relaxation were implemented to minimize IAP. He was discharged from the ICU on postoperative day 4, and discharged from the hospital, on postoperative day 12 (Fig. 1D). Patient is in our service for clinical follow-up for five years, and shows no signs or recurrence.

Fig. 1.

Case 1. (A and B) CT coronal plane (A) and sagittal plane (B) with greater omentum, small bowel, colon and a portion of the liver in the right hemithorax. (C) Thoracotomy in the right 7th intercostal space with extrusion bowel. (D) Chest X-ray on postoperative day 30 showing adequate bilateral lung expansion.

2.2. Patient two

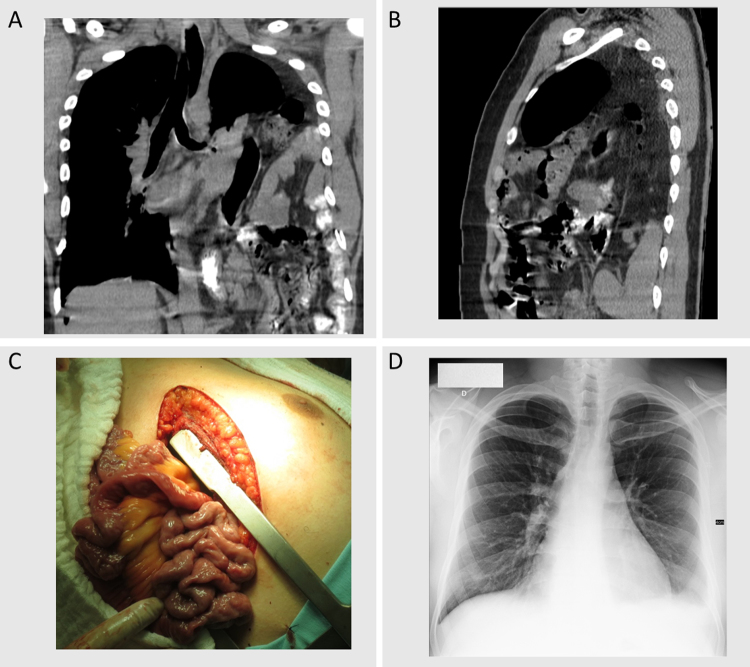

A Brazilian, 25-year-old male presented with the chief complaints of dyspnea and noises in the left thorax during and after meals. No breath sounds were detected in the left chest area; however, bowel sounds were audible. Eight years ago, he had been a victim of motorcycle versus bus accident. Chest tomography confirmed a left diaphragmatic hernia (Fig. 2A and B). The surgery was performed with two incisions: an anterolateral left thoracic incision at the seventh intercostal space (Fig. 2C), and a midline abdominal supraumbilical incision. Exploration of the thoracic cavity revealed a 10-inch annular diaphragmatic defect, which allowed passage of the entire colon and greater omentum, as well as stomach and most of the small bowel (5 cm from the ligament of Treitz to 30 cm before the cecum). The diaphragmatic defect was closed in two layers, using simple sutures (polypropylene 2) with dual mesh (polypropylene/polyethylene) reinforcement at the thoracic interface. Following omentectomy and abdominal closure, the patient was placed in the ICU for a full 24 h, during which ventilatory assistance and complete muscular relaxation were implemented to minimize IAP. He was discharged from the ICU on postoperative day 3 and discharged from the hospital on postoperative day 8 (Fig. 2D). Patient is in our service for clinical follow-up for two years, and shows no signs or recurrence.

Fig. 2.

Case 2. (A and B) CT coronal plane (A) and sagittal plane (B) with greater omentum, stomach, small bowel and colon in the left hemithorax. (C) Thoracotomy in the left 7th intercostal space with extrusion of bowel. (D) Chest X-ray on postoperative day 20 showing bilateral adequate lung expansion.

2.3. Patient three

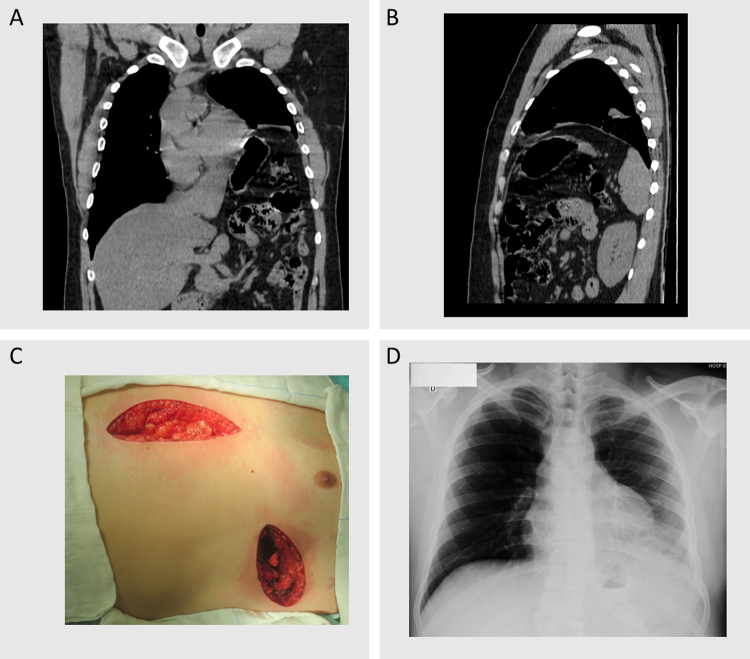

A Brazilian, 32 year old male presented with the chief complaints of a dry cough and dyspnea with moderate exertion. No breath sounds were detected in the lower third of left chest area. Six years ago, he was the victim of penetrating injury to the left thoraco-abdominal transition area. Chest tomography confirmed a left diaphragmatic hernia (Fig. 3A and B). The surgery was performed by two incisions: an anterolateral left thoracic incision at the seventh intercostal space, and a midline abdominal supraumbilical incision (Fig. 3C). Exploration of the thoracic cavity revealed a 2-inch annular diaphragmatic defect, associated with paralysis of the diaphragm and eventration. The diaphragmatic defect was closed in two layers, using simple sutures (polypropylene 2) with dual mesh (polypropylene/polyethylene) reinforcement at the thoracic interface. Following omentectomy and abdominal closure, the patient was placed in the ICU for 24 h, without ventilatory assistance or muscular relaxation. He was discharged from the ICU on the postoperative day 2and discharged from the hospital, on postoperative day 7 (Fig. 3D). Patient is in our service for clinical follow-up for two years, and shows no signs or recurrence.

Fig. 3.

Case 3. (A and B) CT coronal plane (A) and sagittal plane (B) with greater omentum, stomach, small bowel, and colon in the left hemithorax associated with diaphragm eventration. (C) Thoracotomy in the left 7th intercostal space and midline laparotomy. (D) Chest X-ray 0n postoperative day 14 showing appropriate bilateral lung expansion.

2.4. Patient four

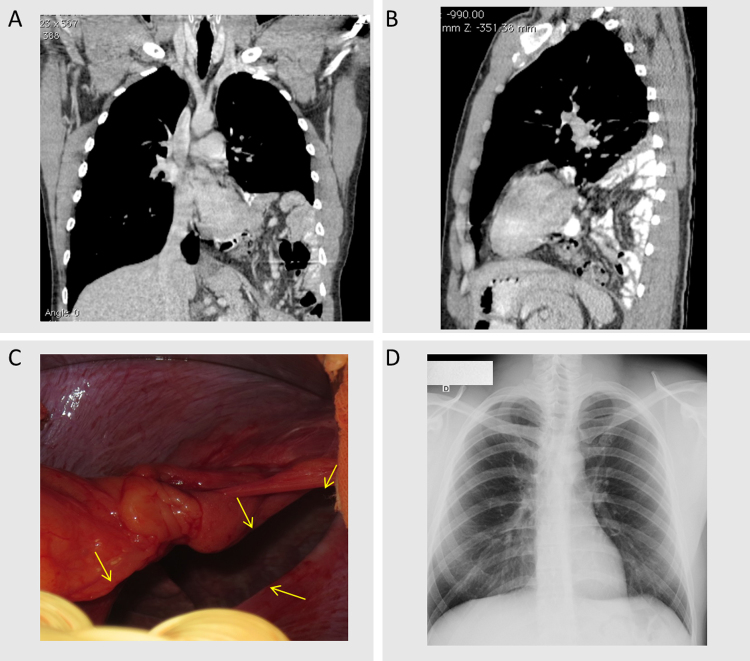

A Brazilian, 24-year-old male presented with the chief complaint of orthopnea. Breath sounds were detected in the entire chest; however, bowel sounds were audible on the left side. Five years ago, he was the victim of a motorcycle fall. Chest tomography confirmed a left diaphragmatic hernia (Fig. 4A and B). The surgery was performed by a midline abdominal supraumbilical incision and video assisted thoracoscopy in the left chest. Exploration of the thoracic cavity revealed a 12 inch annular diaphragmatic defect (Fig. 4C), which allowed passage of a portion of the colon and greater omentum, as well as portions of the stomach and small bowel. The diaphragmatic defect was closed in two layers, using simple sutures (polypropylene 2) without dual mesh reinforcement. The patient was placed in the ICU for 24 h postoperatively, without ventilatory assistance or muscular relaxation. He was discharged from the ICU on the first postoperative day and discharged from the hospital, on the seventh postoperative day (Fig. 4D). Patient is in our service for clinical follow-up for two years, and shows no signs or recurrence.

Fig. 4.

Case 4. (A and B) CT coronal plane (A) and sagittal plane (B) with greater omentum, stomach, small bowel, and colon in the left hemithorax. (C) 12 cm hernial ring image, the arrows indicate the edges of the lesion. (D) Chest X-ray on postoperative day 30 showing adequate bilateral lung expansion.

3. Discussion

Traumatic diaphragmatic rupture is described as a complication of closed or penetrating trauma to the thoraco-abdominal transition area on either side. However, a low index of suspicion at the time of the injury and a lack of adequate diagnostic investigation may exacerbate the situation over the long term. The negative pressure of the thoracic cavity causes a gradually migration of abdominal contents into the chest; this sequestration reduces the abdomen’s ability to maintain the viscera in their normal anatomical position. When the hernia is diagnosed early, the repair is less complicated and requires less invasive surgery. Years after the initial trauma, the diaphragmatic rupture produces dense adhesions between the chest and the abdominal contents. In Case 1, it was necessary to remove a portion of the pericardium that was firmly adherent to the liver. Due to the risk of serious injuries happen during surgery, in none of the cases laparotomy was indicated as unique approach, differently from when the diagnosis of hernia is done early. In Case 4, it was possible to perform video assisted thoracoscopy, with only trocar to optical view that provided a less invasive access for hernia repair. We chose that approach because tomography showed thoracic cavity with partial left lung expansibility (Fig. 4A and B), which was different from the other cases (Figs. 1A, B, 2A, B 3A and B). In all cases, IAP was monitored during abdominal closure and in post operatory evaluation. For that, a three-way bladder catheter was introduced and connected to a device that measured IAP by a scale that measured water centimeters. We had the objective to maintain the IAP less than 22 cm/H2O or 16 mmHg. In cases 1–3, the IAP increased when abdominal closure began; therefore, a total omentectomy was performed. However, despite that procedure, patients 1 and 2 required intensive care, which entailed ventilatory assistance and complete muscular relaxation to maintain the IAP level below 16 mm Hg. Dual mesh was used for reinforcement in cases 1, 2, and 3; this option was based on the difficulty of replacement of the abdominal viscera. Visceral relocation was not difficult in Case 4; thus, this measure was not required.

4. Conclusions

All cases demonstrated that surgical difficulty increases when diaphragmatic rupture is not diagnosed early. It should be noted that when trauma to the thoraco-abdominal transition area is blunt or penetrating, a thorough evaluation is required to rule out diaphragmatic rupture and a regular follow-up to monitor late development of this comorbidity [3,4].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Funding

There were no sources of funding for our research.

Ethical approval

N/A.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for publication of this case reports and accompanying images.

Author contributions

TRN, JCPL and CCIC proceeded surgery and clinical evaluation. TRN, MG, AJR and SS analyzed and reviewed all exams and medical history of the patient regarding this patology. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Guarantor

Tales Rubens de Nadai.

Contributor Information

Tales Rubens de Nadai, Email: talesusp@yahoo.com.br, trnadai@heab.fmrp.usp.br.

José Carlos Paiva Lopes, Email: jcpaivalopes@terra.com.br.

Caio César Inaco Cirino, Email: caiocirino@yahoo.com.br.

Maurício Godinho, Email: godinho.mauricio@gmail.com.

Alfredo José Rodrigues, Email: alfredo@fmrp.usp.br.

Sandro Scarpelini, Email: sandro@fmrp.usp.br.

References

- 1.Meyers B.F., McCabe C.J. Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Occult marker of serious injury. Ann. Surg. 1993;218(6):783–790. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199312000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kozak O. Late presentation of blunt right diaphragmatic rupture (hepatic hernia) Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2008;26(5):638. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.10.032. e3-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turhan K. Traumatic diaphragmatic rupture: look to see. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2008;33(6):1082–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsevych O.Y. Blunt diaphragmatic rupture: four year’s experience. Hernia. 2008;12(1):73–78. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besombe N. Traumatic rupture of the diaphragm report of eleven cases (author’s transl) Acta Chir. Belg. 1975;74(6):616–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mihos P. Traumatic rupture of the diaphragm: experience with 65 patients. Injury. 2003;34(3):169–172. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(02)00369-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotoulas C. Right diaphragmatic rupture and hepatic hernia: a rare late sequela of thoracic trauma. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2004;25(6):1121. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sirbu H. Late bilateral diaphragmatic rupture: challenging diagnostic and surgical repair. Hernia. 2005;9(1):90–92. doi: 10.1007/s10029-004-0243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beigi A.A. Prognostic factors and outcome of traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2010;16(3):215–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]