Highlights

-

•

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head should be included in the differential diagnosis of insufficiency fracture of the femoral neck.

-

•

Enhanced MRI may be useful in determining the existence of extensive osteonecrosis of the femoral head.

Keywords: Occult fracture, Femoral neck, Osteonecrosis of the femoral head

Abstract

Introduction

Although the subchondral portion of the femoral head is a common site for collapse in osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH), femoral-neck fracture rarely occurs during the course of ONFH. We report a case of occult insufficiency fracture of the femoral neck without conditions predisposing to insufficiency fractures, occurring in association with ONFH.

Presentation of case

We report a case of occult fracture of the femoral neck due to extensive ONFH in a 60-year-old man. No abnormal findings suggestive of ONFH were identified on radiographs, and the fracture occurred spontaneously without any trauma or unusual increase in activity. The patient’s medical history, age, and good bone quality suggested ONFH as a possible underlying cause. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging was useful in determining whether the fracture was caused by ONFH or was instead a simple insufficiency fracture caused by steroid use.

Discussion

The patient was treated with bipolar hemiarthroplasty, but if we had not suspected ONFH as a predisposing condition, the undisplaced fracture might have been treated by osteosynthesis, and this would have led to nonunion or collapse of the femoral head. To avoid providing improper treatment, clinicians should consider ONFH as a predisposing factor in pathologic fractures of the femoral neck.

Conclusion

ONFH should be included in the differential diagnosis of insufficiency fracture of the femoral neck.

1. Introduction

Idiopathic osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH) occurs frequently in young and middle-aged patients. The disease frequently leads to progressive collapse of the femoral head, followed by degenerative arthritis of the hip [1–5]. Corticosteroid therapy and alcohol abuse have been identified as risk factors for the development of ONFH [6]. Although collapse usually occurs in the subchondral portion of the femoral head, another fracture site is the junction between necrotic bone and reparative bone [7–9], located in the subcapital area when osteonecrosis involves the whole femoral head. However, insufficiency fracture can occur without an associated history of a recent or unusual increase in activity. The conditions predisposing to insufficiency fractures include osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteogenesis imperfecta, Paget disease, hyperparathyroidism, osteomalacia, fibrous dysplasia, and osteopetrosis. In this report, we describe a case of occult insufficiency fracture of the femoral neck without conditions predisposing to insufficiency fractures, occurring in association with ONFH. No abnormal findings indicative of ONFH were identified in the femoral heads on plain radiographs. The entire femoral head was found to be necrotic, and the fracture occurred at the junction of the necrotic and reparative bone in the femoral neck.

2. Case report

A 60-year-old carpenter who had taken oral steroids daily (prednisolone; daily maximum, 50 mg; daily average, 18 mg) for about 10 months to treat dermatomyositis arrived at our hospital because he experienced sudden pain in his right hip. The patient’s height was 170 cm, his weight was 59 kg, and his body mass index was 20.4 kg/m2. He had no history of trauma or alcohol abuse, but he experienced sudden pain in his right hip joint when he was in a half-sitting posture holding a heavy log (weighing approximately 10 kg) 2 weeks before he visited at our department.

Findings on routine laboratory tests were normal. Physical examination revealed a slight limitation of hip-joint motion: flexion, 90°; abduction, 30°; adduction, 10°; internal rotation, 0°; and external rotation, 40°. His Harris hip score was 75 of a possible 100 points. The bone mineral density for his lumbar spine, measured by dual X-ray absorptiometry, was 0.786 g/cm2 (T score, −1.9). The density was 1.697 g/cm2 for his right femoral head and 0.667 g/cm2 for his right femoral neck, and was 1.693 g/cm2 for left his femoral head and 0.460 g/cm2 for his left femoral neck.

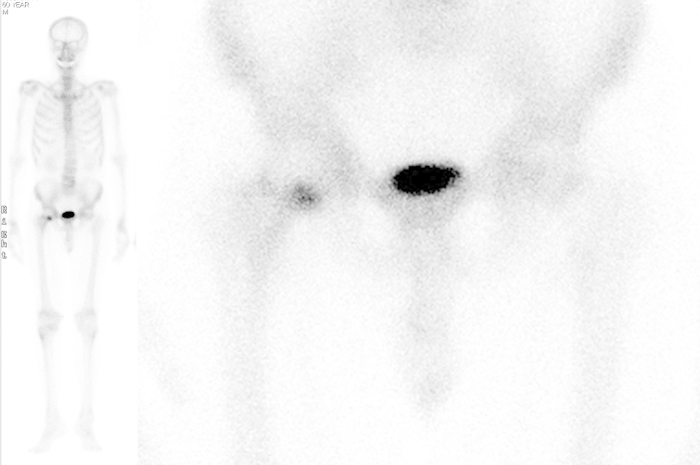

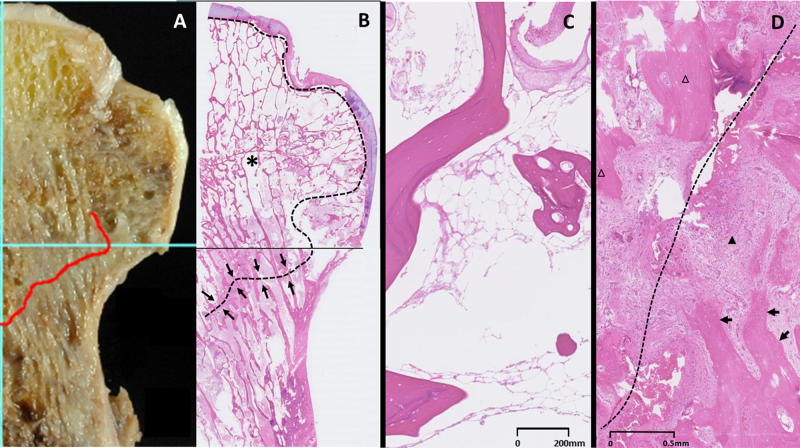

A plain radiograph of the right hip joint showed no signs in particular (Fig. 1), but there was a thick, very-low-signal-intensity band at the medial part of the femoral neck on T1-weighted and T2-weighted magnetic resonance images. Also, a linear low-signal-intensity band extended and descended to the intertrochanteric area on T1-weighted images. Simultaneously, a deep wedge-shaped low-intensity band in the left femoral head, as is seen in primary osteonecrosis, was apparent on T1-weighted images (Fig. 2). The radiologist diagnosed occult fracture of the right femoral neck and osteonecrosis of the left femoral head on the basis of findings on plain radiographs and magnetic resonance images. When bone scintigraphy was performed to confirm the occult fracture, it showed increased uptake in the medial subcapital area. Simultaneously, it seemed to show a decreased uptake in the right femoral head, similar to the left femoral head. Because the femoral head showed a cold uptake, bone scintigraphy raised the question of bilateral ONFH (Fig. 3). Tomosynthesis and computed tomography were also performed on the right hip joint, and images from both processes showed a sclerotic linear lesion in the medial subcapital area (Fig. 4). Finally, we performed gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to determine whether the occult fracture occurred because of an insufficiency fracture or instead because of a pathologic fracture in association with ONFH. The results appeared to indicate that ONFH caused the occult fracture (Fig. 2). On the basis of findings on all images, our diagnosis was occult fracture associated with extensive ONFH.

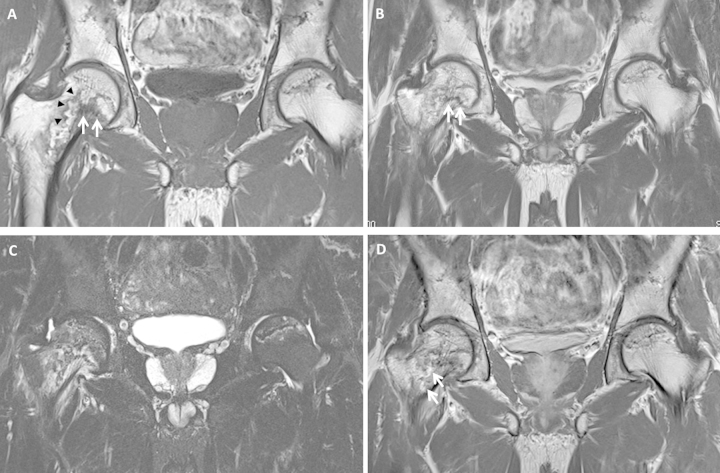

Fig. 1.

Radiographs obtained 2 weeks after the onset of right hip pain. There were no significant findings on either the (A) anteroposterior view or the (B) frog lateral view.

Fig. 2.

Coronal T1-weighted (A) and T2-weighted (B) magnetic resonance images show a thick low-signal-intensity band at the medial part of the femoral neck (white arrows). Furthermore, the irregular, serpentine, low-signal-intensity lesion extended and descended to the intertrochanteric area on T1-weighted images (black arrowheads). A coronal short τ inversion recovery sequence (C) shows an edema pattern in the bone marrow of the right femoral neck. A coronal gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance image (D) shows no contrast enhancement in the proximal segment from the distal low-intensity band. The proximal low-intensity band is not contrast-enhanced, but the distal low-intensity band is partially contrast-enhanced (white arrows).

Fig. 3.

Bone scintigraphy images show increased radionuclide uptake in the medial part of the right femoral neck and decreased uptake in both femoral heads.

Fig. 4.

Tomosynthesis (A) and computed tomography (B) images show a sclerotic lesion in the medial subcapital area (black arrows) that corresponds to the thick, low-signal intensity on T1-weighted and T2-weighted magnetic resonance images.

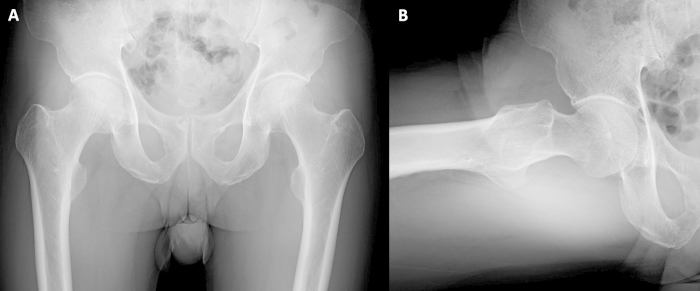

The fracture was treated with bipolar hemiarthroplasty, and the resected femoral head was observed both grossly and microscopically. The femoral heads were fixed in 10% formalin solution, decalcified in 5% nitric acid solution, processed, and embedded in paraffin. The histopathologic diagnosis of osteonecrosis was made when the femoral head showed a zonal pattern with an area of bone infarction, reparative granulation tissue, and viable tissue [10]. Histologic examination showed a typical pattern of dead osteocytes in the trabeculae of the femoral head, which is consistent with a pathologic diagnosis of osteonecrosis. Almost the entire femoral head was necrotic, and adjacent living trabeculae were thickened by appositional new bone. Necrosis was extensive, as we expected, so the choice of bipolar hemiarthroplasty rather than osteosynthesis was correct (Fig. 5). Harris hip score [11] improved preoperatively 76.8–90.5 at the 2-year follow-up. This study was approved by our institution’s review board and the appropriate written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Fig. 5.

Photographs of the mid-coronal plane of the resected femoral head and neck, and the whole mounted histologic specimen (A). Microscopically, the trabecular bone and marrow in the femoral head are extensively necrotic (asterisk, area surrounded by black dotted line) (B). Red line and black arrows indicate the fracture line. A histopathologic image of the necrotic region shows accumulation of bone marrow cell debris, along with bone trabeculae with empty lacunae beneath the fracture line (C). The reactive zone is composed of vascular granulation tissue (solid arrowhead) and trabeculae thickened by the formation of appositional new bone (black arrows). The dotted line indicates the fracture line; the open arrowheads indicate necrotic trabeculae (D).

3. Discussion

Although the subchondral portion of the femoral head is a common site for collapse in osteonecrosis, femoral-neck fracture rarely occurs during the course of ONFH [3,12]. However, it has been reported that when such a fracture does happen, it does so most often without the occurrence of significant trauma, and usually at the junction of the necrotic and reparative bone [7]. Kenzora and Glimcher [12] proposed that the structural breakage of the femoral head in ONFH is initiated by the focal resorption of the subchondral bone plate during the repair process. The breakage can propagate in two different directions. One is via a subchondral fracture through the necrotic area, and the other is via a fracture through the junction of the dead bone and the zone of bone repair. They observed that the fracture tended to occur through the bone repair zone when the necrotic lesion was large. Yang et al. [13]. reported that a fracture in the necrotic lesion appeared in two major locations: the subchondral region and the deep necrotic region near the underlying interface of necrotic and viable bone. Also, the site and size of the necrotic area in the femoral head was suggested to determine the risk of fracture and subsequent collapse. Motomura et al. [14]. demonstrated that collapse in the subchondral region is significantly associated with the location of the medial boundary of the necrotic lesion. However, in femoral heads with large necrotic lesions, they found collapse in another region, including the deep necrotic region near the underlying interface of necrotic and viable bone. In our patient, osteonecrosis involved almost the entire femoral head, and a large part of the fracture occurred through the bone repair zone at the femoral head–neck junction. Our patient was 60 years old, and the quality of his bone was not poor enough for a spontaneous fracture of the femoral neck to occur.

Ikemura et al. [15]. showed the utility of clinical features for the differentiation of subchondral insufficiency fracture from osteonecrosis. They found that when patients did not have a history of corticosteroid intake, the odds ratio for subchondral insufficiency fracture was 5.95 compared with ONFH. Furthermore, when patients did not have a history of either corticosteroid intake or alcohol abuse, the odds ratio for subchondral insufficiency fracture was extremely high (56.01) compared with ONFH. Fortunately, it was apparent that ONFH could be a possible predisposing factor for our patient because the patient had a risk factor for ONFH. ONFH can occur as a complication of femoral-neck fractures, but undisplaced or minimally displaced insufficiency fractures of the femoral neck are complicated by ONFH only on extremely rare occasions [16,17]. In our patient, the medical history, the necrosis of the entire femoral head, and the condition of the contralateral femoral head suggested that the fractures had occurred after the onset of ONFH.

Contrast-enhanced MRI has been used to identify necrotic lesions in patients with ONFH that show a bone marrow edema pattern on nonenhanced MRI, because the pattern complicates the demarcation between living tissue and necrotic lesions [18,19]. Miyanishi et al. [20]. suggested that the presence of contrast enhancement in the segment proximal to the low-signal-intensity band in the femoral head may serve as a supplemental diagnostic measure for the differentiation of subchondral insufficiency fracture from osteonecrosis. We performed contrast-enhanced MRI to verify that our patient’s subcapital fracture was caused by extensive osteonecrosis rather than by simple insufficiency fracture. The results indicated that the fracture was caused by extensive ONFH because the contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance images showed that the segment proximal to the band was not enhanced. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging was useful to clarify the extent of the necrotic lesion and to select the surgical treatment in this case. Subcapital pathologic fracture can occur because of extensive ONFH if there is no history of trauma. There have been some reports of subcapital fractures caused by extensive ONFH [21–24].

The recognition of this fracture is important because treatment with osteosynthesis using hip screws may result in poor clinical outcomes. An investigation of osteonecrosis risk factors and evaluation of the opposite hip are necessary. Osteosynthesis for subcapital fractures that occur after extensive ONFH rarely yields good results. Consequently, these patients should be treated with hip arthroplasty. In our patient, osteonecrosis involved almost the entirety of the right femoral head. In our patient, the pathologic fracture occurred through the junction between the necrotic bone and reparative bone at the subcapital area. If findings from various imaging methods such as radiography, computed tomography, tomosynthesis, MRI, and bone scintigraphy raise suspicion of an insufficiency femoral-neck fracture in a patient who has a sufficient bone quality, the clinician should investigate whether extensive ONFH is hidden. ONFH should be included in the differential diagnosis of insufficiency fracture of the femoral neck. Also, enhanced MRI, rather than unenhanced MRI, may be useful in determining the existence of extensive ONFH.

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest.

Funding

No sources of funding.

Ethical approval

We report about a single case that did not require ethical approval. The manuscript is not a clinical study.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version for publication. Dr. Fukui had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design: Fukui.

Acquisition of data: Fukui.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Fukui, Kaneuji, Matsumoto.

Key learning points

-

•

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head should be included in the differential diagnosis of insufficiency fracture of the femoral neck.

-

•

Enhanced MRI may be useful in determining the existence of extensive ONFH.

Acknowledgments

Medical editor Katharine O’Moore-Klopf, ELS (East Setauket, NY, USA) provided professional English-language editing of this article.

References

- 1.Bradway J.K., Morrey B.F. The natural history of the silent hip in bilateral atraumatic ONFH. J. Arthroplasty. 1993;8:383–387. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(06)80036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugano N., Atsumi T., Ohzono K., Kubo T., Hotokebuchi T., Takaoka K. The 2001 revised criteria for diagnosis, classification, and staging of idiopathic ONFH of the femoral head. J. Orthop. Sci. 2002;7:601–605. doi: 10.1007/s007760200108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merle d’Aubigne R., Postel M., Mazabraud A., Massias P., Gueguen J., France P. Idiopathic necrosis of the femoral head in adults. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1965;47:612–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patterson R.J., Bickel W.H., Dahlin D.C. Idiopathic avascular necrosis of the head of the femur: a study of fifty-two cases. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1964;46A:267–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohzono K., Saito M., Takaoka K. Natural history of nontraumatic avascular necrosis of the femoral head. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1991;73:68–72. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B1.1991778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Assouline-Dayan Y., Chang C., Greenspan A., Shoenfeld Y., Gershwin M.E. Pathogenesis and natural history of osteonecrosis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:94–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Usui M., Inoue H., Yukihiro S. Femoral neck fracture following avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Acta Med. Okayama. 1996;50:111–117. doi: 10.18926/AMO/30487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim Y.M., Lee S.H., Lee F.Y., Koo K.H., Cho K.H. Morphologic and biomechanical study of avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Orthopedics. 1991;14:1111–1116. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19911001-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Debeyre J., Kénési C., Boucker C. [3 cases of spontaneous cervico-capital fractures, complications of primary necrosis of the femur head.] Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. 1969;36:23–26. [Article in French.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto T., DiCarlo E.F., Bullough P.G. The prevalence and clinicopathological appearance of extension of osteonecrosis in the femoral head. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1999;81:328–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris W.H. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end result study using a new method of result evaluation. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1969;51:737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenzora J.E., Glimcher M.J. Pathogenesis of idiopathic osteonecrosis: the ubiquitous crescent sign. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1985;16:681–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang J.W., Koo K.H., Lee M.C. Mechanics of femoral head osteonecrosis using three-dimensional finite element method. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2002;122:88–92. doi: 10.1007/s004020100324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motomura G., Yamamoto T., Yamaguchi R. Morphological analysis of collapsed regions in osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2011;93:184–187. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B225476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikemura S., Yamamoto T., Motomura G., Nakashima Y., Mawatari T., Iwamoto Y. The utility of clinical features for distinguishing subchondral insufficiency fracture from osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2013;133:1623–1627. doi: 10.1007/s00402-013-1847-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johansson C., Ekenman I., Tornkvist H. Stress fractures of the femoral neck in athletes. The consequence of a delay in diagnosis. Am. J. Sports Med. 1990;18:524–528. doi: 10.1177/036354659001800514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blickenstaff L.D., Morris J.M. Fatigue fracture of the femoral neck. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1966;48:1031–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahnken A.H., Staatz G., Ihme N., Günther R.W. MR signal intensity characteristics in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. Value of fat-suppressed (STIR) images and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images. Acta Radiol. 2002;43:329–335. doi: 10.1080/j.1600-0455.2002.430317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vande B., erg B.E., Malghem J.J., Labaisse M.A., Noel H.M., Maldague B.E. MR imaging of avascular necrosis and transient marrow edema of the femoral head. Radiographics. 1993;13:501–520. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.13.3.8316660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyanishi K., Hara T., Kaminomachi S., Maeda H., Watanabe H., Torisu T. Contrast-enhanced MR. imaging of subchondral insufficiency fracture of the femoral head: a preliminary comparison with that of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2009;129:583–589. doi: 10.1007/s00402-008-0642-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee J.S., Suh K.T. A pathological fracture of the femoral neck associated with osteonecrosis of the femoral head and a stress fracture of the contralateral femoral neck. J. Arthroplasty. 2005;20:807–810. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim Y.M., Kim H.J. Pathological fracture of the femoral neck as the first manifestation of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J. Orthop. Sci. 2000;5:605–609. doi: 10.1007/s007760070013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoon T.R., Rowe S.M., Song E.K., Mulyadi D. Unusual osteonecrosis of the femoral head misdiagnosed as a stress fracture. J. Orthop. Trauma. 2004;18:43–47. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200401000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Min B.W., Koo K.H., Song H.R. Subcapital fractures associated with extensive osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2001;390:227–231. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200109000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]