Abstract

Objective

To present the design of the Bypassing the Blues (BtB) study to examine the impact of a collaborative care strategy for treating depression among patients with cardiac disease. Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery is one of the most common and costly medical procedures performed in the US. Up to half of post-CABG patients report depressive symptoms, and they are more likely to experience poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL), worse functional status, continued chest pains, and higher risk of cardiovascular morbidity independent of cardiac status, medical comorbidity, and the extent of bypass surgery.

Methods

BtB was designed to enroll 450 post-CABG patients from eight Pittsburgh-area hospitals including: (1) 300 patients who expressed mood symptoms preceding discharge and at 2 weeks post hospitalization (Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) ≥10); and (2) 150 patients who served as nondepressed controls (PHQ-9 <5). Depressed patients were randomized to either an 8-month course of nurse-delivered telephone-based collaborative care supervised by a psychiatrist and primary care expert, or to their physicians’ “usual care.” The primary hypothesis will test whether the intervention can produce an effect size of ≥0.5 improvement in HRQoL at 8 months post CABG, as measured by the SF-36 Mental Component Summary score. Secondary hypotheses will examine the impact of our intervention on mood symptoms, cardiovascular morbidity, employment, health services utilization, and treatment costs.

Results

Not applicable.

Conclusions

This effectiveness trial will provide crucial information on the impact of a widely generalizable evidence-based collaborative care strategy for treating depressed patients with cardiac disease.

Keywords: depression, coronary artery bypass surgery, randomized clinical trial, collaborative care, coronary artery disease

INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery is one of the most common and costly medical procedures performed in the US with >400,000 surgeries performed annually (1) at an average charge of approximately $60,000. Its main indications are the relief of angina and improvement in quality of life, and it clearly benefits most patients. However, up to half of post-CABG patients report depressive symptoms in the perioperative period, and they are more likely to experience poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL), worse functional status, and continued chest pains. They also are at higher risk of rehospitalization and death after the procedure independent of cardiac status, medical comorbidity, the extent of bypass surgery, and despite a satisfactory surgical result (2–5).

The exact mechanism whereby depression affects post-CABG outcomes is currently unknown and is likely multifactorial (6–8). Nevertheless, interventions to detect and then effectively manage depression in cardiac populations are of great interest because depression is a treatable determinant of HRQoL. Improving HRQoL is a key indication for CABG surgery. Safe and effective treatments for depression of low cardiovascular toxicity are available (6), and proven delivery care approaches within organized healthcare systems exist (9), even for patients with chronic medical conditions (10–12). Nevertheless, the optimal time to assess, implement, and provide depression treatment after a cardiac event remains unknown as elevated mood symptoms post cardiac events may spontaneously remit (13–18), overlap with symptoms of the underlying medical or surgical condition (e.g., fatigue, sleeplessness), or manifest weeks after the cardiac event (15–18).

Several randomized trials of depression interventions in cardiac populations have been conducted (13,14,19,20); yet, none addressed post-CABG depression or utilized the “collaborative care” approach recently endorsed by a National Heart Lung Blood Institute (NHLBI) expert consensus panel (8). Unlike the Sertraline Antidepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHART) (14) intervention for depressed patients with post myocardial infarction (MI) that relied on a single antidepressant, or the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) (13,21) and Cardiac Randomized Evaluation of Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Efficacy (CREATE) (20) trials that used a single antidepressant in combination with a counseling modality for treating depressed post-MI and coronary artery disease (CAD) patients, respectively, collaborative care emphasizes a more flexible real-world treatment “package” (22). It includes active, sustained follow-up by a nurse or other nonphysician allied health professional “care manager” who adheres to an evidence-based treatment protocol and—in a critical distinction with earlier depression treatment trials in patients with cardiac disease—routinely communicates treatment recommendations with patient’s primary care physicians (PCPs) and with a mental health specialist (MHS) when indicated (23,24). These care managers also support patients with the time and frequency of contacts necessary—often by telephone—to educate them about their condition, assess treatment preferences, teach self-management techniques, proactively monitor patients’ therapeutic response, suggest adjustments in care consistent with the patient’s treatment history, preferences, and insurance restrictions, and bridge transitions between various clinical settings (e.g., inpatient, outpatient, rehabilitation) and providers.

A recent meta-analysis of 37 randomized trials of collaborative care for depressed primary care patients reported a pooled effect size (ES) of 0.25 (95% Confidence Interval = 0.18–0.32) on mood symptoms (9), similar to the ES obtained from more intensive forms of face-to-face psychotherapy (25), of antidepressant pharmacotherapy (26,27), and observed in the ENRICHD, SADHART, and CREATE trials. Clinical trials have also demonstrated the effectiveness of collaborative care at improving clinical outcomes post MI (28), among patients with congestive heart failure (29), diabetes (11), and other general medical conditions (30), and at a lower total cost of care (29,31), particularly among the more severely ill (30), and even outside the framework of a trial (32).

Study Overview

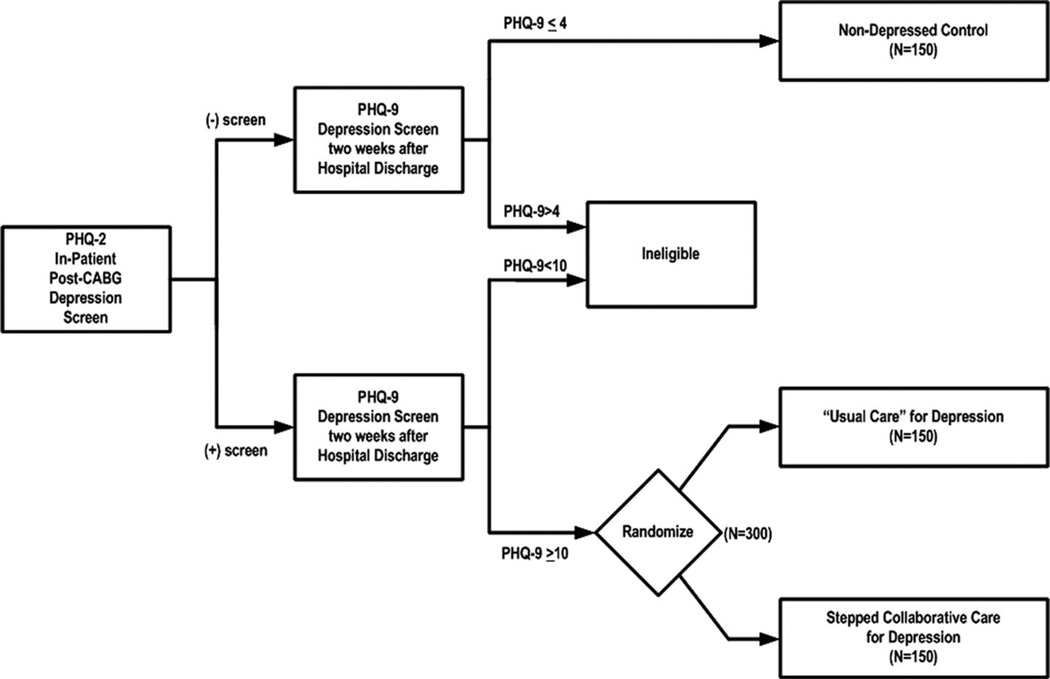

The NHLBI-funded Bypassing the Blues (BtB) trial is the first to examine the effectiveness of collaborative care at treating post-CABG depression or depression in any other cardiac population. It was designed to enroll 450 post-CABG patients from eight Pittsburgh-area hospitals including: (1) 300 patients who express mood symptoms before discharge and at 2 weeks post hospitalization (Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) ≥10); and (2) 150 patients who serve as nondepressed controls (PHQ-9 <5) to facilitate comparisons with depressed study patients and help identify the optimal timing and subgroups to screen for post-CABG depression (Figure 1). To maximize both the external and internal validity of our study, we applied standardized patient inclusion criteria, random assignment of patients, blinded assessments of clinical outcomes, standardized implementation of our treatment protocol across multiple recruitment sites, and included patients covered by a variety of insurance plans.

Figure 1.

Bypassing the Blues study design. PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire.

Our primary hypothesis will test whether telephone-based collaborative care for depression can produce at least a clinically meaningful 0.5 ES improvement in HRQoL at 8 months post surgery, as measured by the SF-36 Mental Component Summary (MCS) score (33), compared with patients who received their doctors’ “usual care” for depression. To promote uptake of our treatment strategy if proven effective, BtB will also examine the impact of treating post-CABG depression on a broad range of outcomes including cardiovascular morbidity, employment, health services utilization, and healthcare costs. Moreover, our depressed “usual care” and nondepressed “control” cohorts will help identify the natural course of post-CABG mood symptoms and the optimal time to screen these patients for depression.

Patient Recruitment

Study Hospitals

To promote the generalizability of our findings, we screened post-CABG patients for depression at eight Pittsburgh-area hospitals including two university-affiliated teaching hospitals, five community hospitals, and a Veterans Administration Medical Center.

To encourage subject recruitment, we identified a thoracic surgeon or cardiologist at each study hospital to serve as the site’s principal investigator. We also contacted other thoracic surgeons, cardiologists, nursing staff, and cardiac rehabilitation specialists at each hospital to: (1) introduce our nurse-recruiters; (2) deliver educational in-service and grand rounds presentations about the links between depression and cardiovascular morbidity and the significance of our study; and (3) establish collaborative relationships. Before initiating recruitment, we also developed press releases and newsletter articles to familiarize hospital staff with our study, and we created a series of Institutional Review Board-approved wall posters and brochures to inform physicians, hospital staff, patients, and their families about the impact of depression on cardiovascular disease and our study.

Patient Identification

Recruiting patients into the BtB protocol required that we evaluate a potential patient’s eligibility on several diagnostic and clinical criteria in a manner that minimally burdened the individual and hospital personnel. It did not depend on physician recognition of the patient’s depressive disorder.

As the psychological and physical symptoms of depression overlap with the post-CABG state and comorbid physical illness, diagnosing depression in medically ill populations can be challenging. Perioperative elevations in depressive symptoms often remit spontaneously post CABG and may be due to the short-term effects of surgery or hospitalization (15,17,18,34,35). Yet, if symptoms due to surgery or physical illness are attributed to depression (e.g., fatigue), then we may falsely label patients as depressed, inappropriately enroll them into our study, and potentially provide unnecessary treatment. However, if their symptoms are misattributed to a concurrent physical illness, effective depression treatment may be withheld.

The most common strategies used to diagnose psychiatric disorders in physically ill patients are the “inclusive,” “etiologic,” and “substitutive” approaches (36,37), and they generally produce similar prevalence rates for major depression (38). We applied the “etiologic” approach which counts symptoms toward a depression diagnosis unless they are clearly and fully accounted for by a general medical condition in accordance with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria. Accordingly, we trained our nurse-recruiters to probe further when a patient acknowledged fatigue, difficulty concentrating, or appetite and sleep disturbances that may be related to the bypass surgery itself or to another medical condition.

Regarding the optimal time to screen for depression, we attempted to screen patients for mood symptoms just before CABG in our pilot work (39). However, this strategy produced an inadequate enrollment rate as many patients were admitted to the hospital early on the morning of their surgery, were transferred the preceding evening from another institution, and/or the procedure was performed on an emergency basis. We also considered screening after hospital discharge. However, this would have required patients to return to the hospital or to our study offices to provide written consent for trial enrollment. Ultimately, we decided to screen post-CABG patients before hospital discharge and then confirm their elevated mood symptoms via telephone 2 weeks later (Figure 1). This strategy: (1) facilitated collection of signed informed consent; (2) created the potential for post-CABG depression screening to become integral to the discharge planning process; and (3) provided an opportunity for developing substantial rapport between the nurse-recruiter, the patient, and possibly a family member who could promote study enrollment and retention.

Patient Screening and Consent Process

Each nurse-recruiter utilized a password-protected Tablet PC laptop (Toshiba M200, Tokyo, Japan) to record patient responses at the bedside into formatted data entry questionnaires (Microsoft Access). The forms guided the recruiter through our enrollment procedure, using skip patterns, dialogue-box prompts, and other error checking routines. Later, we transferred data from the Tablet PC into our trial’s paperless data management system via password-protected USB jump-drives.

Our nurse-recruiters approached physicians, nurses, cardiac rehabilitation personnel, and other staff who had routine clinical contact with post-CABG patients to inquire if they were caring for any medically stable patients who were at a minimum of 2 days post surgery. In keeping with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, our recruiters asked these hospital personnel to discuss our research project with their potentially eligible patients and then obtain patient agreement to release their names and room numbers. If the patient agreed, the nurse-recruiter approached him/her, explained our study screening procedure, and sought the patient’s signed informed consent. We used the two-item PHQ-2 (40,41) to screen patients for depression and considered an affirmative answer to either item as a positive screen (90% sensitivity) (40).

Depressed Trial Cohort

If the patient screened positive for mood symptoms and met a preliminary review of our inpatient protocol-eligibility criteria (Table 1), the recruiter administered the Folstein Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE) (42). We required an MMSE score of ≥24 to ensure that each patient was mentally competent to provide informed consent and reliable responses to our assessment instruments. Patients using an antidepressant medication at the time of hospital admission or post surgery were eligible to participate, provided they met all other protocol-eligibility criteria. On confirmation of these criteria, our study nurse sought the patient’s signed consent to enroll in the clinical trial.

TABLE 1.

Protocol-Eligibility Criteria for Bypassing the Blues

| Inpatient criteria | |

| 1. | Has just undergone CABG (combined or redo procedure) |

| 2. | Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) ≥24 |

| 3. | Able to be evaluated and treated for depression as an outpatient post CABG |

| 4. | Has a household telephone |

| 5. | Not presently in treatment with a mental health specialist |

| 6. | No active suicidality |

| 7. | No history of psychotic illness |

| 8. | No history of bipolar illness according to subject self-report and past medical history |

| 9. | No current alcohol dependence or other substance abuse as evidenced by chart review and the CAGE questionnaire (88) |

| 10. | No organic mood syndromes, including those secondary to medical illness or drugs |

| 11. | Presence of noncardiovascular conditions likely to be fatal within 1 year |

| 12. | No unstable medical condition as indicated by history, physical, and/or laboratory findings |

| 13. | No previous enrollment in the study cohort |

| 14. | English speaking, and not illiterate or possessing any other communication barrier |

| 15. | If nondepressed control, no current or previous diagnosis or treatment of depression |

| Outpatient criteria | |

| 16. | Continue to meet all above inpatient criteria |

| 17. | A PHQ score of ≥10 if PHQ-2 positive screen as an inpatient |

| 18. | A PHQ score of <5 if PHQ-2 negative screen as an inpatient |

CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire.

All PHQ-2 positive patients received their doctors’ “usual” post discharge medical care. We also encouraged patients during and post hospitalization via a mailed letter sent to them and to their PCP that the patient seek follow-up for the depressive symptoms and treatment if indicated. We additionally provided all patients completing our screening procedure with the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) brochure “Depression and Heart Disease” (43) to destigmatize depression, raise patients and family members awareness of the impact of mood disorders on heart disease, and educate them about treatment options. Although these efforts are ethically necessary given the findings by our group (44,45) and others (46), we believe this information only minimally affects the overall outcomes (44–47). Physicians concerned about their patient’s psychiatric state could also initiate treatment for depression at any time before hospital discharge, regardless of the patient’s decision to enroll in our study.

Two-Week Follow-Up

We used the nine-item PHQ-9 (48) to assess mood symptoms by telephone approximately 2 weeks post hospital discharge. We required that patients score ≥10 to remain protocol-eligible, a threshold that signified at least a moderate level of depressive symptoms (48) and has been described as “virtually diagnostic” for depression among patients with cardiac disease (90% specific) (40). We selected the PHQ-9 given its ability to be self-administered or administered by medical staff with minimal training, negligible response burden, validity for telephone administration, and growing popularity in clinical practice and research protocols (8).

Randomization

If the patient met all protocol-eligibility criteria and agreed to continue in our trial, the paperless data-management system automatically randomized him/her to either our intervention or “usual care” group. Randomization occurred in a 1:1 ratio according to a statistician-prepared computer-generated random assignment sequence stratified by hospital recruitment site.

To maintain the treatment blind after the 2-week call, the telephone assessor informed the study project coordinator that the diagnostic interview was completed. The project coordinator then logged-in to the study’s data-management system to determine the patient’s randomization status. If he/she was randomized to our intervention, the project coordinator e-mailed the nurse-recruiter who enrolled the patient and requested the nurse to inform the patient via telephone and commence our treatment protocol. However, if the patient was randomized to “usual care,” then the project coordinator telephoned the patient to inform him/her of their status. Regardless of randomization status, we mailed the patient and his/her PCP a letter indicating that the patient was experiencing an elevated level of mood symptoms requiring follow-up to decide the level of attention required for these symptoms. The patient also received a $20 check as reimbursement for the time and effort required to complete our 2-week baseline assessment and to promote adherence with future assessments.

Nondepressed Control Cohort

We programmed our nurses’ Tablet PCs to sample randomly approximately one nondepressed study subject for every two enrolled depressed study subjects, stratified by study hospital and gender, and oversampled by race. Operationally, when a post-CABG patient screened negative on the inpatient PHQ-2 (69% specificity) (40), was not using an antidepressant, and met all other protocol-eligibility criteria, the Tablet PC generated a prompt that signaled the nurse if the patient was selected randomly to participate. We later administered the PHQ-9 at 2 weeks post hospitalization and required that the patient score 0 to 4 to remain protocol-eligible. To simplify our study design, we classified as protocol-ineligible any post-CABG patient who initially screened negative on the PHQ-2 but scored ≥5 on the follow-up PHQ-9 (Figure 1).

Intervention

Initial Telephone Contact

After the nurse-recruiter/care manager informed the patient that he/she was randomly selected for our intervention, the nurse: (1) reviewed the patient’s psychiatric history including use of any nonprescription medications or herbal supplements used to self-medicate depressive symptoms; (2) discussed the patient’s medical history with a particular emphasis on his/her cardiac history (e.g., smoking, diabetes); (3) provided basic education about depression, its impact on cardiac disease, and various self-management strategies; and (4) assessed the patient’s treatment preferences for depression.

Many depressed patients, particularly the elderly and those with a significant burden of medical comorbidity, are either unwilling or unable to adhere to successive face-to-face encounters with a therapist (13) or to accept antidepressant pharmacotherapy. Additionally, the majority of depressed patients prefer to receive care for their symptoms from their PCP rather than an MHS (49). Therefore, in keeping with principles of shared decision-making (50), we provided patients with oral and written educational materials about their condition (“bibliotherapy”), and offered a variety of treatment options: (1) initiation or adjustment of antidepressant pharmacotherapy provided under their PCP’s direction; (2) referral to a community MHS; (3) a combination of the above; or (4) “watchful-waiting” if the patient’s mood symptoms were only mildly elevated (PHQ-9 score of 10–14) and he/she had no prior history of depression (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Overview of Intervention and Symptom Monitoring by Group

| Nondepressed Control | Depressed “Usual Care” | Depressed Intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | |||

| Informed of elevated post-CABG mood symptoms before hospital discharge | N/A | • | • |

| Given brochure on depression and heart disease | • | • | • |

| PHQ-9 administered 2 weeks after hospital discharge | • | • | • |

| Informed of randomization/control status | • | • | • |

Nurse care manager phones at regular intervals × 8 months to:

|

• | ||

| Suggest/facilitate mental health specialty referral when appropriate | Per Data Safety Monitoring Plan | Per Data Safety Monitoring Plan and upon request | • |

| After 8 months blinded assessor monitors for development/relapse of depression | • | • | • |

| Physician | |||

| Informed of patient’s elevated mood symptoms at baseline by letter | • | • | |

| Informed of patient’s randomization status at 2 weeks by letter | • | ||

| Provided guidance re: antidepressant pharmacotherapy | Upon request | • | |

| Can initiate, adjust, or discontinue pharmacotherapy as indicated | • | • | • |

| Provided feedback regarding patient’s progress with depression self-management workbook and pharmacotherapy, as applicable | • | ||

| Offered assistance referring their patient to a mental health specialist | Upon request | Upon request | • |

| Informed of patient’s preferences for treatment at 8 months | • | ||

| Informed if depression relapses post remission | • | • | |

| Informed if patient’s clinical status significantly worsens | • | • | • |

| Informed of patient’s clinical status at end of intervention | N/A | N/A | • |

| Informed of patient’s clinical status and at end of study enrollment | • | • | • |

CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire.

Beginning with the initial telephone contact, our care managers devoted significant time to educating patients about their disorder and attempting to impart durable self-management skills. Thus, they advised all patients to: (1) get sufficient rest; (2) engage in appropriate exercise and other pleasurable activities; and (3) avoid tobacco, alcohol, and unhealthy foods. They also offered to review the NIMH brochure on depression and heart disease distributed earlier (43), and provided opportunities for the patient to ask questions about their conditions.

Bibliotherapy

To impart self-management skills, the nurse care manager mailed a copy of “The Depression Helpbook” (51) to all intervention patients. We selected it given data from two separate primary care trials supporting its effectiveness when utilized under the supervision of a trained care manager (52,53). It integrates both a psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic approach to managing depression in a flexible manner so that patients learn to handle depression, formulate treatment-related decisions, acquire skills and confidence to self-manage these episodes, and develop maintenance strategies. It also presents detailed information about the impact of depression on comorbid medical illnesses and pharmacologic treatments that the patient can use for later reference.

The care manager telephoned patients approximately every other week to review lesson plans and to practice the skills imparted through regular performance of homework assignments. Depending on the patient’s motivation to complete workbook assignments and whether he/she accepted antidepressant pharmacotherapy, this period of frequent contact typically continued for 2 to 6 months. The patient subsequently transitioned to the “continuation phase” of treatment during which the care manager contacted him/her less frequently until the end of our 8-month intervention.

Pharmacotherapy

Trials of single antidepressant agents typically demonstrate 45% to 65% efficacy at producing a treatment response (14,54–57). We also appreciate from our experiences that many depressed individuals, particularly older ones and those already prescribed multiple medications, often refuse antidepressant pharmacotherapy. Many patients who agree to enrolling in an antidepressant trial do so reluctantly, and/or report troubling side effects that contribute to premature discontinuation.

Six selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for treating depression, and there is no evidence that any one SSRI is preferable for treating naïve patients (58,59). Furthermore, all are believed safe for use in cardiac patients (14,60–63), and there is indirect evidence that SSRIs could reduce cardiovascular morbidity (14,21,64). Therefore, when an intervention patient agreed to a trial of antidepressant pharmacotherapy and had no history of SSRI treatment for a depressive episode or brand preference, we recommended citalopram as our initial medication as it: (1) has limited drug-drug interactions— particularly with coumadin and digoxin, two medications commonly used by cardiac patients; (2) requires few dosage adjustments; (3) is available in generic form; (4) has well-established efficacy; and (5) is generally well tolerated by patients. Citalopram is also an appropriate first-choice SSRI, given its use as the initial medication in both the NIMH-funded Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (PROSPECT) (60) and Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) (55) trials.

As in PROSPECT and STAR*D, we recommended that patients who responded poorly or were unable to tolerate citalopram switch to another SSRI, an effective strategy in approximately 20% to 50% of patients who failed an initial SSRI trial (56,65). We generally attempted two SSRI trials before recommending a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), as the latter may elevate blood pressure, particularly at higher dosages (66). If our care manager elicited a history of painful diabetic neuropathy, we recommended the SNRI duloxetine as it is FDA-approved for treatment of both that condition as well as depression. If the patient failed to respond to two or three trials of an SSRI or SNRI or experienced troubling side effects (e.g., impotence), then we recommended bupropion, another antidepressant with low cardiovascular toxicity, and included in the PROSPECT (60) and STAR*D (65) treatment algorithms (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Preferred Antidepressants for Use in the Bypassing the Blues Trial

| Generic Name | Trade Name | Class | Starting Dosage |

Step-Up Dose |

Target Dose | Top Dose/d | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-line | |||||||

| Citaloprama | Celexa (Forest Pharmaceuticals, St. Louis, MO) | SSRI | 10 mg/d | 10–20 mg/d | 20–40 mg/d | 60 mg | Fewer cytochrome p450 drug-drug interactions (e.g., digoxin, warfarin) |

| Fluoxetinea | Prozac (Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN) | SSRI | 10 mg/d | 10 mg/d | 20–40 mg/d | 80 mg | Most activating of the SSRI; slower onset of action; no taper-off required |

| Paroxetinea | Paxil (GlaxoSmithKline, Middlesex, UK) | SSRI | 10 mg/d | 10–20 mg/d | 40 mg/d | 60 mg | Slightly sedating |

| Sertralinea | Zoloft (Pfizer, New York, NY) | SSRI | 25 mg/d | 25–50 mg/d | 100 mg/d | 200 mg | Taper-off period recommended |

| Escitalopram | Lexapro (Forest Pharmaceuticals, St. Louis, MO) | SSRI | 5 mg/d | 5–10 mg/d | 20 mg/d | 20 mg | Fewer cytochrome p450 drug-drug interactions (e.g., digoxin, warfarin); fewer dosing intervals |

| Second-line | |||||||

| Venlafaxine XR | Effexor XR (Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc, Madison, NJ) | SNRI | 37.5 mg/d | 37.5 mg/d | 75–150 mg/d | 225 mg | May increase blood pressure at higher doses |

| Duloxetine | Cymbalta (Eli Lilly) | SNRI | 20 mg/d | 10–20 mg/d | 60 mg/d | 120 mg | May increase blood pressure at higher doses; FDA approved for diabetic peripheral neuropathy pain and urinary incontinence |

| Bupropion SRa | Wellbutrin SR (GlaxoSmithKline, Middlesex, UK) | NDRI | 100 mg/d | 50 mg/bid | 150 mg/bid | 400 mg | Fewer sexual side effects than SSRIs/SNRIs; FDA approved to help with tobacco cessation; may induce seizures at higher doses in seizure-prone individuals |

| Mirtazapinea | Remeron (Organon, a Schering-Plough company, Kenilworth, NJ) | tetracyclic | 15 mg qhs | 15 mg qhs | 30 mg qhs | 45 mg qhs | Highly sedating; orthostatic hypotension can occur; may raise cholesterol |

Generic available.

d = day; NDRI = norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor; SNRI = serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

We periodically encountered intervention patients who were using an SSRI at a guideline-recommended dosage and duration at baseline. Although these patients may be “well managed,” we did not consider them adequately treated because they were still experiencing at least a moderate level of depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 ≥10). We, therefore, recommended that their medication be increased to the maximum daily dosage, if tolerated, before switching to another SSRI, SNRI, or bupropion. Patients generally agreed with this management strategy (67,68) as they were familiar with their current medication’s side effects, if any, and occasionally hesitated to try new and unfamiliar ones. This approach also helped to confirm that the patient failed to respond to an adequate trial of the medication before changing to another. However, when the patient was using a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) or a benzodiazepine (BZD) as their antidepressant, we recommended that the PCP instead initiate a trial with an SSRI, given the potential toxicity of TCAs in cardiac patients (62) and the ineffectiveness of BZDs at treating depression (69).

We made treatment recommendations in accordance with each patient’s treatment preferences, prior medication experience, and insurance coverage. PCPs could accept or reject these recommendations and they were responsible for prescribing and approving adjustments to their patients’ pharmacotherapy as we neither prescribed nor distributed antidepressant medications to study patients. To promote adherence with our treatment recommendations, our nurse care managers offered to call in antidepressant prescriptions to patients’ pharmacies under their PCPs’ verbal orders, and then forwarded an order sheet for the PCP to sign and return to document it. Given the relationships we established with patients and their PCPs, it was very uncommon for a PCP not to follow our treatment recommendations. In those few instances, our care managers continued to monitor the patient and provide the PCP with clinical updates and new treatment recommendations as indicated.

Promoting Medication Adherence

Some patients agreed to a trial of antidepressant pharmacotherapy but then declined or quickly discontinued it because of cost, side effects, or concerns about dependence, safety, or stigma. In these instances, particularly if the patient remained symptomatic, care managers attempted to overcome the patient’s reluctance, using various motivational interviewing approaches (70,71). Care managers also provided educational materials, including the workbook (51), that might mitigate any concerns, and emphasized they would monitor the patient’s clinical status closely and report back to the clinical team and PCP for ongoing guidance. The care manager also informed the PCP about the patient’s reason(s) for nonadherence in the possibility the clinician could help overcome the patient’s resistance.

Although distinguishing true medication side effects from symptoms of the underlying mood or cardiac condition can be difficult, it was important to do so because somatic complaints resembling medication side effects often remit after resolution of the underlying depression (72). Therefore, our care managers made extensive efforts to have patients continue their antidepressant medications for at least 4 to 6 weeks so as to permit a potential treatment response to occur in keeping with guideline-recommended practice (69).

If the patient used pharmacotherapy but not the self-management workbook, or vice versa, and did not respond to treatment after 6 weeks, we then recommended combining the two treatment modalities. If the patient remained symptomatic, the nurse care manager encouraged the patient to seek additional depression care from an MHS and offered assistance in doing so.

Mental Health Referral

Our telephone-based stepped collaborative care approach was not designed to replace face-to-face care delivered by an MHS. Thus, the care manager advised the PCP to refer the patient to a local MHS in cases of poor response to our depression intervention, severe psychopathology, complex psychosocial problems, and/or patient preference in keeping with our stepped care approach. If the PCP agreed or if the patient desired referral to an MHS, the care manager offered to assist by identifying a provider within the patient’s insurance network, and/or by offering to telephone a local MHS’s office to arrange the initial appointment. After the date of the scheduled visit, the care manager contacted the patient to confirm that the appointment was kept. Once the patient initiated MHS treatment, the care manager continued to telephone the patient monthly to: (1) monitor his/her mood symptoms; (2) relay clinical information to both our clinical management team and the patient’s PCP; and (3) promote adherence with follow-up appointments.

Treatment Declined

When a patient lacked interest in any active depression treatment modality, the care manager continued to contact the patient monthly to reassess his/her mood and attempted to encourage the patient to initiate treatment. If the patient remained uninterested, the nurse informed the patient’s PCP via telephone, fax, and/or mailed letter as clinically appropriate.

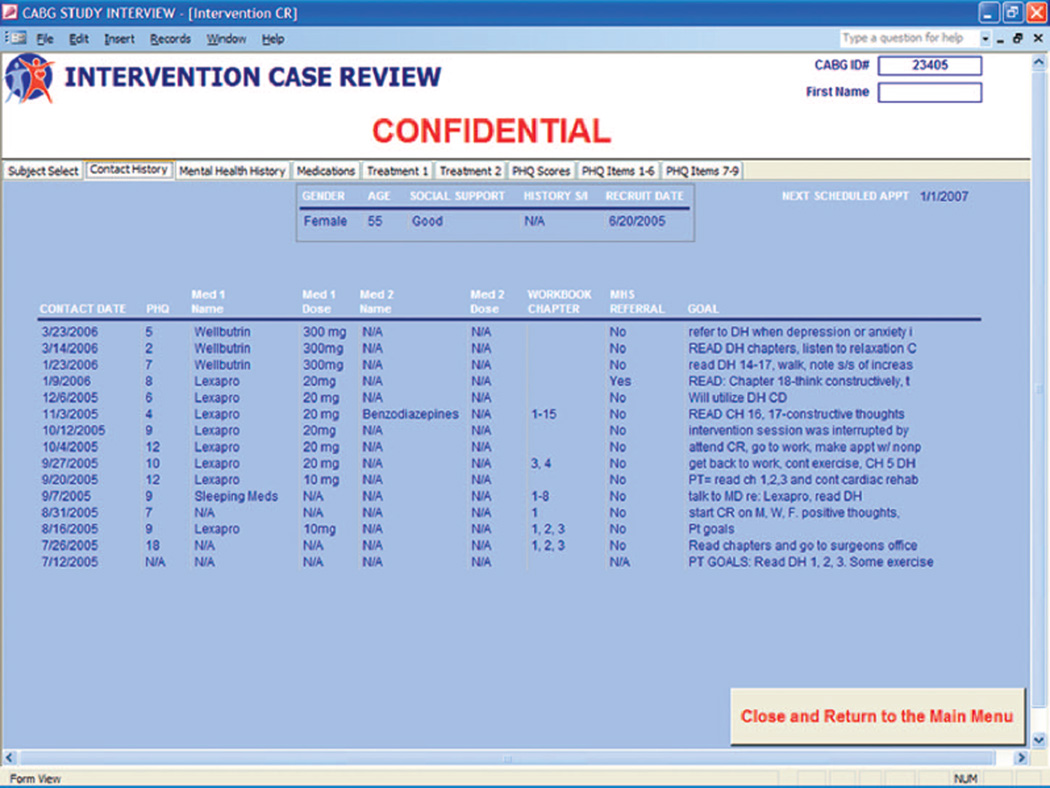

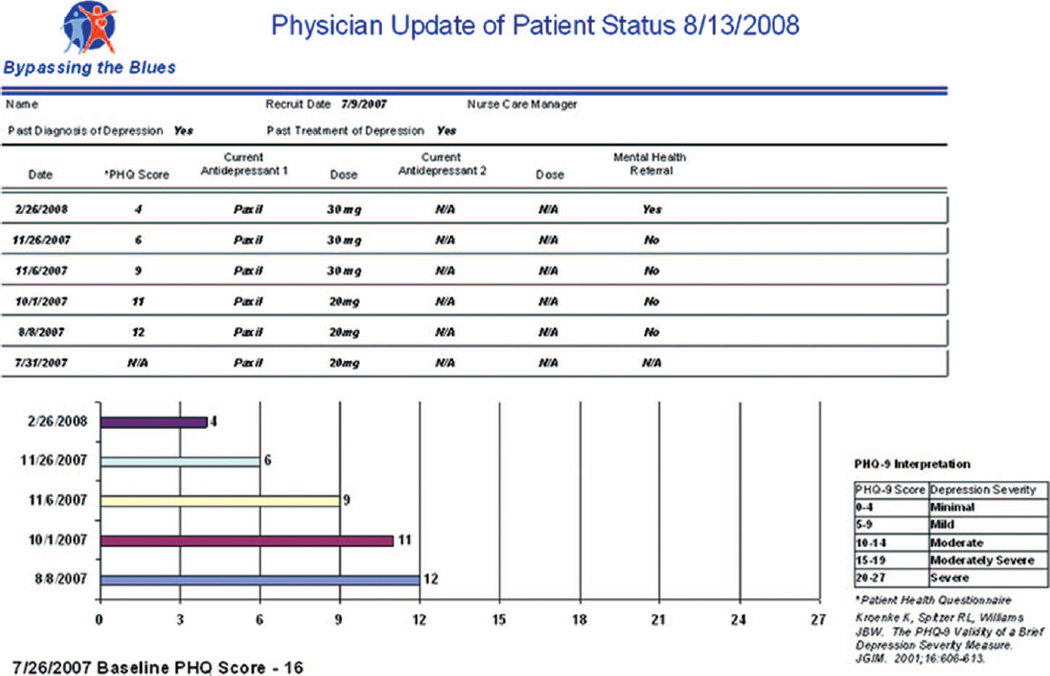

Monitoring Treatment

Care managers used their Tablet PCs to chart telephone intervention encounters directly into our paperless data management system. In keeping with Wagner’s model (23), the system functioned effectively as a registry that allowed a care manager to: (1) view and track key process measures of care (e.g., clinical notes, PHQ-9 scores, treatment(s) accepted, date of last contact, treatment goals); (2) generate structured reporting forms for discussion at our weekly case-review sessions (Figure 2); and (3) create structured form letters for mailing to patients’ PCPs to keep them apprised of their patients’ progress and invite feedback (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Sample overview screenshot portraying a particular intervention patient’s progress with our treatment algorithm. Note serial Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) scores, pharmacotherapy usage, workbook lesson plans, and specialty referral.

Figure 3.

Example of a structured form letter report sent to a patient’s primary care physician to keep them informed of their patients’ progress. The patient and nurse care manager’s names have been removed to protect their identities. PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire.

Weekly Case-Review

After the initial patient contact, the study nurse presented the patient’s clinical information to the “clinical management team” that consisted of the study psychiatrist (C.F.R.), psychologist (B.H.B.), and internist (B.L.R.). To facilitate our weekly hour-long review sessions, we utilized an LCD projector to display our patient registry on a conference room wall. That projector was connected to a Tablet PC linked to our study’s data management system via a conference room intranet port. Among the projected screens were: (1) the registry list of each nurse’s intervention patients so as to focus group discussion on newly randomized patients and those with the highest levels of depressive symptoms; (2) an overview of a particular patient’s progress including serial PHQ-9 scores, pharmacotherapy usage, workbook lesson plans, and MHS referral status (Figure 2); (3) additional clinical details to inform decision-making (e.g., past and family history of depression and prior antidepressant usage); and (4) scores on individual PHQ-9 items to identify the precise domains where the patient was having difficulty (e.g., sleep).

After discussion, the clinical management team typically formulated one to three treatment recommendations the nurse conveyed to the patient via telephone. The nurse documented these treatment recommendations into our data management system, and provided an update about the patient at our next weekly case-review session. Patients and their PCPs could accept or reject our treatment recommendations as well as obtain care outside of study treatment.

Telephone Follow-Up

The care manager readministered the PHQ-9 at regular intervals so as to track the patient’s depressive symptoms and inform treatment recommendations generated at our weekly case-review sessions. The care manager telephone follow-up contacts occurred approximately biweekly and lasted 15 to 45 minutes in keeping with the patient’s distress level, severity of mood symptoms, questions about his/her care, and use of the self-management workbook (Table 2). After a complete recovery (PHQ-9 <5) on two or more consecutive contacts, we considered a patient to be in the “continuation phase” of treatment (69) and moved him/her to a monthly schedule of telephone follow-up.

Suicidal Ideation

We monitored all patients’ psychiatric status through periodic telephone assessments, a practice useful in identifying emerging suicidal ideation or plans (73). We programmed our paperless data management system so that whenever suicidal ideation was uncovered by either our care managers or blinded assessors during routine administration of our rating scales and entered into the appropriate electronic form, it triggered the automatic launch of our online suicide protocol form.

Our suicide protocol form systematically guided our research staff through probes to determine the suicidal ideation’s frequency, chronicity, content, and threat level (e.g., guns in the home, lives alone). If the protocol classified the patient at moderate or high risk, the team member immediately paged the study psychiatrist (C.F.R.), or his on-call psychiatrist-delegate, to review the clinical information and to determine the level of attention the symptoms warranted. Depending on the situation, the psychiatrist telephoned the patient directly to elicit further details or provided the care manager with guidance on managing the situation. The psychiatrist or care manager also informed the patient’s PCP about the patient’s suicidality so that he/she could contact the patient and arrange follow-up as clinically necessary.

After the initial suicidal threat, we telephoned patients 1, 3, 7, and 30 days later to monitor their clinical status and confirm follow-up with our recommended treatment plan. Although we did not otherwise directly interact with nonintervention patients or with their physician(s) to direct treatment, we offered to assist any patient or clinician regardless of intervention status by providing the names and contact information of local MHS professionals and by answering questions about a patient’s psychiatric condition as appropriate.

Concluding the Intervention

Approximately 6 months post randomization, the care manager began to prepare patients for their 8-month end-of-intervention telephone call. If the patient’s mood symptoms completely remitted (PHQ-9 score of <5), then our care managers promoted continued adherence with the current treatment modality. However, if they did not sufficiently remit (i.e., PHQ-9 score of >10), then our care managers recommended initiation of or a change in pharmacotherapy, or referral to an MHS if not previously done so. In an effort to increase patient motivation and urgency during the terminal phase of treatment, the care manager reminded the patient that regular telephone contacts would soon conclude and that symptoms and treatment would not be monitored beyond the end of intervention.

After the end-of-intervention call, the nurse care manager summarized the patient’s clinical course at the weekly casereview session. The care manager subsequently sent the patient a letter describing the patient’s current level of depressive symptoms, care preferences, and our clinical management team’s final treatment recommendations. To promote adherence and to reduce the risk for miscommunications, we also sent a copy of this letter to the patient’s PCP.

Data Collection and Monitoring

Outcome Assessments

We employed a team of trained assessors blinded to a patient’s treatment assignment and baseline depression status (depressed or nondepressed) to determine the impact of our intervention strategy. The assessors conducted telephone research assessments at 2, 4, 8, and 12 months and then semiannually until the last enrolled patient completed their 8-month follow-up assessment, a time-point corresponding with the approximate end of the continuation phase of depression treatment (follow-up range: 8–48 months). To promote adherence with our multiple assessment procedures, we paid participants $20 for each completed interview and mailed them an annual birthday card.

We selected the widely used and well-validated SF-36 (33) as our main “generic” outcome measure of HRQoL to facilitate comparisons of our study findings with other trials. To better evaluate the impact of post-CABG depression and of our intervention on self-reported outcomes, we also administered the: (1) Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) to assess “disease-specific” HRQoL (74); (2) Health and Work Performance Questionnaire to evaluate patients’ ability to return to work (75); (3) the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRS-D) portion of the ENRICHD trial’s Depression Interview and Structured Hamilton (76) to assess mood symptoms; and (4) a popular measure of adherence with cardiac treatment recommendations (77).

Key Events Classification

Our blinded assessors inquired routinely about any emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and mental health visits patients may have experienced since their last telephone assessment. Whenever they detected a potential “key event,” we requested a copy of relevant medical records (e.g., emergency room record, hospital discharge summary, and/or death certificate) from the hospital where the event occurred. We forwarded these records to two physician members of our Key Events Classification Committee who were blinded as to the patient’s depression and intervention status to: (1) classify the nature of the event as cardiac, cardiovascular, psychiatric, or “other”; (2) provide a level of certainty to their decision (“probable” versus “definite”); and (3) describe the event. If the physician-reviewers were not in complete (100%) agreement (e.g., “probable cardiac” versus “definite cardiac”), then the event was brought to a Committee meeting for discussion and final adjudication by consensus.

Economic Assessments

We obtained from patients at the time of study enrollment signed consent to obtain medical claims data from their insurance carrier. We will use these consents to obtain information regarding the types, dates, and costs of services patients received (e.g., inpatient hospital stay, outpatient physician visit), and CPT4 codes for each episode of care. We will combine this information with patient self-reports of medication use to estimate total medical costs per patient, and work outcomes (75) to assess the “business case” for treating post-CABG depression (31,78,79).

Study Monitoring Procedures

Assessments

We converted the paperless data entry screens used by our nurse-recruiters into a computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) system that guided our blinded assessors through each telephone interview and ensured each form was fully completed. We programmed our system to prompt assessors with timely reminders to ensure each follow-up assessment was performed according to schedule or rescheduled as soon as possible, and that participant payments were properly distributed and accounted for. To provide additional quality assurance, we digitally recorded our study assessments and conducted periodic spot-checks of these recordings to: (1) confirm patients’ responses were rated accurately and corresponded with those entered into our CATI system; (2) review interactions with suicidal patients; and (3) provide feedback to assessors on their performance. We also utilized these audiofiles to train new study assessors and to determine interrater reliability.

Data Safety Monitoring

We programmed our data management system to identify all subjects whose follow-up HRS-D score increased by >25% from their 2-week baseline score. We examined these subjects’ clinical records on at least a monthly basis, and, if indicated, informed the treating PCP via letter. The letter also offered the physician assistance in obtaining the names and phone numbers of local MHSs. Other than this procedure and when a patient expressed suicidal ideation, we made no further attempts to alter the medical care provided to our depressed and nondepressed control patients.

Study Progress

The study project coordinator and principal investigator utilized our data management system to generate up-to-date administrative reports that monitored: (1) trial enrollment by study hospital, patient gender, and race; (2) care managers’ caseloads; (3) rates of follow-up assessments; (4) missed study assessments so that patients may be recontacted; (5) patients’ clinical status for data safety monitoring purposes; and (6) potential protocol deviations that the study investigators review at staff meetings as appropriate.

Sample Size Calculations

BtB’s primary hypothesis will use an intent-to-treat approach to test whether our intervention will produce a moderate ES of ≥0.5 improvement in HRQoL at 8 months post surgery, as measured by the SF-36 MCS, compared with patients who receive their PCPs’ “usual care” for depression. We selected this time point to test our primary hypothesis to allow: (1) a therapeutic alliance to develop between patients, their PCPs, and our care managers; (2) modality time to change their mind for those patients initially unwilling or uninterested in trying any treatment, especially if their mood symptoms fail to remit; and (3) sufficient time for several therapeutic trials, if necessary, of antidepressant pharmacotherapy and counseling to take effect.

Depressed post-MI women exposed to a psychosocial intervention may experience worse cardiac outcomes than women exposed to a control condition or to men (13,19), and other reports suggested women derive less benefit from CABG surgery than men (80–84). Therefore, we powered BtB to conduct a subgroup analysis of our intervention by gender. We calculated that, if half of our depressed trial cohort are women (n = 150) and we encountered 10% attrition from our telephone assessments, we would have 83% power to detect an ES difference of 0.5 in the SF-36 MCS at 8 months by gender (two-tailed α = 0.05). Applying the same assumptions to our full sample (n = 300), would provide 90% power to detect an ES difference of 0.40, and 80% power to detect a small but clinically meaningful ES difference of 0.30.

Our secondary hypotheses will test whether intervention patients compared with our depressed “usual care” group experience: (1) fewer cardiovascular events, reduced health services utilization, and lower treatment costs; (2) similar levels of HRQoL post surgery as our nondepressed post-CABG cohort; and (3) greater adherence with process measures for treating CAD (e.g., aspirin and lipid-lowering therapy). Although our secondary hypotheses focus on 8-month outcomes in parallel with our primary hypothesis, we will collect follow-up data ranging from 8 to 51 months (median = 27 months) that will permit us to: (1) assess the durability of our depression intervention; (2) observe the course of mood symptoms in our control groups (Figure 1); and (3) better evaluate the impact of post-CABG depression and its treatment on cardiovascular morbidity, health services utilization, and treatment costs, particularly if they lag changes in HRQoL and mood symptoms.

It is difficult to speculate on any improvement that may derive from our intervention for most of our secondary outcomes as data to guide us are lacking. Most post-CABG patients in the early years after the procedure generally do well medically compared with patients with other cardiovascular disease. Still, our pilot data (39) and other published evidence suggest depressed post-CABG patients have higher rates of rehospitalization for cardiovascular causes (5) and mortality (4) than do nondepressed CABG patients. Based on this information, we estimated that 20% of our nondepressed post-CABG patients (n = 150) and 40% of depressed post-CABG patients would be rehospitalized for any cardiac cause over the 12 months post surgery. Using log-rank methods and assuming ≤5% of patients are lost to follow-up and a two-tailed α < 0.05, we will have 97% power to detect a 50% reduction in hospitalizations (40% versus 20% rate of hospitalization).

Data Analyses

Our primary analyses will use an intent-to-treat approach to compare mean group score (e.g., SF-36 MCS, DASI, HRS-D) and time to an event (e.g., rehospitalization) differences from baseline to 8-month follow-up to estimate the magnitude of benefits that can be expected from our collaborative care intervention in routine clinical practice. We will also examine differences between treatment arms and with our nondepressed control arm on various process of care measures (e.g., rate of follow-up contacts), health services utilization, and work outcomes (e.g., days absent, hours worked per week) using mixed-effects repeated-measures models that include time, gender, race, treatment, and interaction terms to compare treatment responses within various subgroups of interest. In addition, we will utilize Kaplan-Meier survival analysis techniques and multivariate Cox regression models to analyze time-to-event data (e.g., death, rehospitalization, and return to work).

We will conduct our economic analyses using all utilization data collected either through insurance claims or by patient self-report (e.g., medication usage). First, we will apply standardized Medicare reimbursement rates and other validated methods to calculate total outpatient and inpatient medical costs per patient. Then, we will employ methods by Katon et al. (85) to estimate the direct program costs of our intervention, using 50% of the Medicare reimbursement for individual psychotherapy (CPT 90804) for each telephone counseling session, and adding the Medicare reimbursement for a single psychiatrist medication management visit (CPT 90862) for each intervention subject. As the distribution of medical cost data are often skewed because a small number of patients incur extremely high costs, we will transform our data to satisfy the underlying distributional assumptions pertaining to our statistical analyses, and use the medical component of the Consumer Price Index to adjust all costs to the start of patient enrollment in 2004.

We will conduct our cost-effectiveness analysis from the perspective of the health insurance payer as this stakeholder is likely to be most influential in developing and sustaining a program resembling our intervention. To calculate the differential cost-effectiveness of our intervention strategy, we will calculate the mean number of depression-free-days (DFD) experienced by subjects in each study arm, and then apply standardized methodology to calculate the incremental cost per additional DFD (86). To facilitate comparisons between the incremental cost-utility ratio of our intervention to other medical interventions, we will transform our SF-36 data into a preference-based utility to calculate quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) (87), and then divide the incremental range of QALYs into our point-estimate of incremental costs to estimate the incremental cost per QALY between intervention arms. Finally, we will conduct sensitivity analyses to analyze the robustness of our assumptions and conclusions (e.g., varying the costs of our intervention strategy).

CONCLUSION

BtB is the first randomized clinical trial to examine the impact of a real-world collaborative care strategy for treating depression in post-CABG patients or any other cardiac population. If found effective, the generalizability of our treatment strategy is enhanced by multiple design features including: (1) use of a simple, validated, two-stage depression screening procedure that can be implemented by nonresearch clinical personnel; (2) a centralized telephone-based intervention; (3) reliance on a variety of safe, effective, simple-to-dose and increasingly generic pharmacotherapy options, a commercially available workbook, and community MHSs to deliver step-up care; (4) use of trained nurses as care coordinators across treatment delivery settings and providers; (5) consideration of patients’ prior treatment experiences, current care preferences, and insurance coverage when recommending care; and (6) an informatics infrastructure designed to document and promote delivery of evidence-based depression treatment, care coordination, and efficient internal operations. Finally, BtB will provide crucial information on when during the post-CABG recovery process to assess for and then implement evidence-based treatment for depression, and the magnitude of benefits that can be expected.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 HL70000 (B.L.R.) and P30 MH71944 (C.F.R.). Clinical trials.gov identifier: NCT00091962.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2008 Update. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association; [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mallik S, Krumholz HM, Lin ZQ, Kasl SV, Mattera JA, Roumains SA, Vaccarino V. Patients with depressive symptoms have lower health status benefits after coronary artery bypass surgery. Circulation. 2005;111:271–277. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000152102.29293.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rumsfeld JS, Ho PM, Magid DJ, McCarthy M, Jr, Shroyer AL, MaWhin-ney S, Grover FL, Hammermeister KE. Predictors of health-related quality of life after coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1508–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumenthal JA, Lett HS, Babyak MA, White W, Smith PK, Mark DB, Jones R, Mathew JP, Newman MF, Investigators N. Depression as a risk factor for mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery. Lancet. 2003;362:604–609. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connerney I, Shapiro PA, McLaughlin JS, Bagiella E, Sloan RP. Relation between depression after coronary artery bypass surgery and 12-month outcome: a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;358:1766–1771. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06803-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vieweg WV, Julius DA, Fernandez A, Wulsin LR, Mohanty PK, Beatty-Brooks M, Hasnain M, Pandurangi AK. Treatment of depression in patients with coronary heart disease. Am J Med. 2006;119:567–573. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Sherwood A, Strauman T, Robins C, Newman MF. Depression as a risk factor for coronary artery disease: evidence, mechanisms, and treatment. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:305–315. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000126207.43307.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson KW, Kupfer DJ, Bigger JT, Califf RM, Carney RM, Coyne JC, Czajkowski SM, Frank E, Frasure-Smith N, Freedland KE, Froelicher ES, Glassman AH, Katon WJ, Kaufmann PG, Kessler RC, Kraemer HC, Krishnan KR, Lespe´rance F, Rieckmann N, Sheps DS, Suls JM National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute Working Group. Assessment and treatment of depression in patients with cardiovascular disease: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group Report. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:645–650. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000233233.48738.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, Simon G, Ludman E, Russo J, Ciechanowski P, Walker E, Bush T. The pathways study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1042–1049. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams JW, Jr, Katon W, Lin EH, Noel PH, Worchel J, Cornell J, Harpole L, Fultz BA, Hunkeler E, Mika VS, Unutzer J, Investigators I. The effectiveness of depression care management on diabetes-related outcomes in older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:1015–1024. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-12-200406150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams LS, Kroenke K, Bakas T, Plue LD, Brizendine E, Tu W, Hendrie H. Care management of poststroke depression: a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke. 2007;38:998–1003. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000257319.14023.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, Carney RM, Catellier D, Cowan MJ, Czajkowski SM, DeBusk R, Hosking J, Jaffe A, Kaufmann PG, Mitchell P, Norman J, Powell LH, Raczynski JM, Schneiderman N. Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients Investigators (ENRICHD). Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the enhancing recovery in coronary heart disease patients (ENRICHD) randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:3106–3116. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glassman AH, O’Connor CM, Califf RM, Swedberg K, Schwartz P, Bigger JT, Jr, Krishnan KR, van Zyl LT, Swenson JR, Finkel MS, Landau C, Shapiro PA, Pepine CJ, Mardekian J, Harrison WM, Barton D, McLvor M Sertraline Antidepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHEART) Group. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA. 2002;288:701–709. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pirraglia PA, Peterson JC, Williams-Russo P, Gorkin L, Charlson ME. Depressive symptomatology in coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14:668–680. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199908)14:8<668::aid-gps988>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKhann GM, Borowicz LM, Goldsborough MA, Enger C, Selnes OA. Depression and cognitive decline after coronary artery bypass grafting. Lancet. 1997;349:1282–1284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09466-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Timberlake N, Klinger L, Smith P, Venn G, Treasure T, Harrison M, Newman SP. Incidence and patterns of depression following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Psychosom Res. 1997;43:197–207. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duits AA, Duivenvoorden HJ, Boeke S, Taams MA, Mochtar B, Krauss XH, Passchier J, Erdman RA. The course of anxiety and depression in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45:127–138. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Prince RH, Verrier P, Garber RA, Juneau M, Wolfson C, Bourassa MG. Randomised trial of home-based psycho-social nursing intervention for patients recovering from myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1997;350:473–479. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Koszycki D, Laliberte MA, van Zyl LT, Baker B, Swenson JR, Ghatavi K, Abramson BL, Dorian P, Guertin MC, Investigators C. Effects of citalopram and interpersonal psychotherapy on depression in patients with coronary artery disease: the Canadian cardiac randomized evaluation of antidepressant and psychotherapy efficacy (CREATE) trial. JAMA. 2007;297:367–379. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor CB, Youngblood ME, Catellier D, Veith RC, Carney RM, Burg MM, Kaufmann PG, Shuster J, Mellman T, Blumenthal JA, Krishnan R, Jaffe AS, Investigators E. Effects of antidepressant medication on morbidity and mortality in depressed patients after myocardial infarction. Arch Gen Psych. 2005;62:792–798. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bower P, Gilbody S, Richards D, Fletcher J, Sutton A. Collaborative care for depression in primary care. Making sense of a complex intervention: systematic review and meta-regression. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:484–493. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.023655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74:511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagner EH. More than a case manager. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:654–656. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-8-199810150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Churchill R, Hunot V, Corney R, Knapp M, McGuire H, Tylee A, Wessely S. A systematic review of controlled trials of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of brief psychological treatments for depression. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5:1–173. doi: 10.3310/hta5350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walsh BT, Seidman SN, Sysko R, Gould M. Placebo response in studies of major depression: variable, substantial, and growing. JAMA. 2002;287:1840–1847. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.14.1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ. Size of treatment effects and their importance to clinical research and practice. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:990–996. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeBusk R, Miller N, Superko H, Dennis C, Thomas R, Lew H. A case-management system for coronary risk factor modification after acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:721–729. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-9-199405010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1190–1195. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wasson J, Gaudette C, Whaley F, Sauvigne A, Baribeau P, Welch HG. Telephone care as a substitute for routine clinic follow-up. JAMA. 1992;267:1788–1793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon GE, Katon WJ, Lin EH, Rutter C, Manning WG, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Young BA. Cost-effectiveness of systematic depression treatment among people with diabetes mellitus. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:65–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glasgow RE, Funnell MM, Bonomi AE, Davis C, Beckham V, Wagner EH. Self-management aspects of the improving chronic illness care breakthrough series: Implementation with diabetes and heart failure teams. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:80–87. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2402_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User’s Manual. 2nd ed. Boston: New England Medical Center; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burker EJ, Blumenthal JA, Feldman M, Burnett R, White W, Smith LR, Croughwell N, Schell R, Newman M, Reves JG. Depression in male and female patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Br J Clin Psychology. 1995;34:119–128. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1995.tb01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rymaszewska J, Kiejna A, Hadry T. Depression and anxiety in coronary artery bypass grafting patients. Eur Psychiatry. 2003;18:155–160. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(03)00052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG, Krishnan KR, Sibert TE. Profile of depressive symptoms in younger and older medical inpatients with major depression. JAGS. 1993;41:1169–1176. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb07298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koenig HG, Pappas P, Holsinger T, Bachar JR. Assessing diagnostic approaches to depression in medically ill older adults: how reliably can mental health professionals make judgments about the cause of symptoms? JAGS. 1995;43:472–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams JW, Jr, Noel PH, Cordes JA, Ramirez G, Pignone M. Is this patient clinically depressed? JAMA. 2002;287:1160–1170. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rollman B, Hanusa B, Sefcik T, Schulberg H, Reynolds C. The prevalence and impact of depressive symptoms on patients awaiting CABG Surgery. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(1):144. [Google Scholar]

- 40.McManus D, Pipkin SS, Whooley MA. Screening for depression in patients with coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:1076–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatric Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Depression and Heart Disease. NIH Publication No. 02–5004. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rollman BL, Hanusa BH, Gilbert T, Lowe HJ, Kapoor WN, Schulberg HC. The electronic medical record: a randomized trial of its impact on primary care physicians’ initial management of major depression. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:189–197. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rollman BL, Hanusa BH, Lowe HJ, Gilbert T, Kapoor WN, Schulberg HC. A randomized trial using computerized decision support to improve the quality of treatment for major depression in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:493–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10421.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Callahan CM, Hendrie HC, Dittus RS, Brater DC, Hui SL, Tierney WM. Improving treatment of late life depression in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:839–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pignone MP, Gaynes BN, Rushton JL, Burchell CM, Orleans CT, Mul-row CD, Lohr KN. Screening for depression in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:765–776. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-10-200205210-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brody DS, Khaliq AA, Thompson TL. Patients’ perspectives on the management of emotional distress in primary care settings. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:403–406. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Social Sci Med. 1999;49:651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Katon W, Ludman E, Simon G. The Depression Helpbook. Boulder, CO: Bull Publishing; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G, Walker E, Unutzer J, Bush T, Russo J, Ludman E. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1109–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Katon W, Rutter C, Ludman EJ, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G, Bush T, Walker E, Unutzer J. A randomized trial of relapse prevention of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:241–247. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rush AJ, Kraemer HC, Sackeim HA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, Frank E, Ninan PT, Thase ME, Gelenberg AJ, Kupfer DJ, Regier DA, Rosenbaum JF, Ray O, Schatzberg AF, Force AT. Report by the ACNP task force on response and remission in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychophar-macology. 2006;31:1841–1853. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Warden D, Ritz L, Norquist G, Howland RH, Lebowitz B, McGrath PJ, Shores-Wilson K, Biggs MM, Balasubramani GK, Fava M, Team SDS. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:28–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kroenke K, West SL, Swindle R, Gilsenan A, Eckert GJ, Dolor R, Stang P, Zhou XH, Hays R, Weinberger M. Similar effectiveness of paroxetine, fluoxetine, and sertraline in primary care: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2001;286:2947–2955. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.23.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mulrow CD, Williams JW, Jr, Chiquette E, Aguilar C, Hitchcock-Noel P, Lee S, Cornell J, Stamm K. Efficacy of newer medications for treating depression in primary care patients. Am J Med. 2000;108:54–64. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whooley MA, Simon GE. Managing depression in medical outpatients. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1942–1950. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hansen RA, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Gaynes BN, Carey TS. Efficacy and safety of second-generation antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:415–426. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-6-200509200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mulsant BH, Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Katz IR, Abrams R, Oslin D, Schulberg HC, The PSG. Pharmacological treatment of depression in older primary care patients: the PROSPECT algorithm. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;16:585–592. doi: 10.1002/gps.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roose SP, Glassman AH, Attia E, Woodring S, Giardina EG, Bigger JT., Jr Cardiovascular effects of fluoxetine in depressed patients with heart disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:660–665. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.5.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roose SP, Laghrissi-Thode F, Kennedy JS, Nelson JC, Bigger JT, Jr, Pollock BG, Gaffney A, Narayan M, Finkel MS, McCafferty J, Gergel I. Comparison of paroxetine and nortriptyline in depressed patients with ischemic heart disease. JAMA. 1998;279:287–291. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Glassman AH, Rodriguez AI, Shapiro PA. The use of antidepressant drugs in patients with heart disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sauer W, Berlin J, Kimmel S. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;104:1894–1898. doi: 10.1161/hc4101.097519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Stewart JW, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Ritz L, Biggs MM, Warden D, Luther JF, Shores-Wilson K, Niederehe G, Fava M, Team SDS. Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafax-ine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1231–1242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thase ME, Tran PV, Wiltse C, Pangallo BA, Mallinckrodt C, Detke MJ. Cardiovascular profile of duloxetine, a dual reuptake inhibitor of serotonin and norepinephrine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:132–140. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000155815.44338.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ruhe HG, Huyser J, Swinkels JA, Schene AH. Dose escalation for insufficient response to standard-dose selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depressive disorder: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:309–316. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.018325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ruhe HG, Huyser J, Swinkels JA, Schene AH. Switching antidepres-sants after a first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1836–1855. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Depression in Primary Care. Vol 1. Detection and Diagnosis. Vol 2. Treatment of Major Depression. Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York: The Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rollnick S, Kinnersley P, Stott N. Methods of helping patients with behaviour change. BMJ. 1993;307:188–190. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6897.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rollman BL, Block MR, Schulberg HC. Symptoms of major depression and tricyclic side effects in primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:284–291. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.012005284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Katz II, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, Brown GK, McAvay GJ, Pearson JL, Alexopoulos GS. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hlatky MA, Boineau RE, Higginbotham MB, Lee KL, Mark DB, Califf RM, Cobb FR, Pryor DB. A brief self-administered questionnaire to determine functional capacity (The Duke Activity Status Index) Am J Cardiology. 1989;64:651–654. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kessler RC, Barber C, Beck A, Berglund P, Cleary PD, McKenas D, Pronk N, Simon G, Stang P, Ustun TB, Wang P. The World Health Organization health and work performance questionnaire (HPQ) J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:156–174. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000052967.43131.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Freedland KE, Skala JA, Carney RM, Raczynski JM, Taylor CB, Mendes De Leon CF, Ironson G, Youngblood ME, Rama Krishnan KR, Veith RC. The depression interview and structured Hamilton (DISH): rationale, development, characteristics, and clinical validity. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:897–905. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000028826.64279.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ziegelstein RC, Fauerbach JA, Stevens SS, Romanelli J, Richter DP, Bush DE. Patients with depression are less likely to follow recommendations to reduce cardiac risk during recovery from a myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1818–1823. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hlatky MA, Rogers WJ, Johnstone I, Boothroyd D, Brooks MM, Pitt B, Reeder G, Ryan T, Smith H, Whitlow P, Wiens R, Mark DB. Medical care costs and quality of life after randomization to coronary angioplasty or coronary bypass surgery. Bypass angioplasty revascularization investigation (BARI) investigators. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:92–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701093360203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mark DB, Lam LC, Lee KL, Jones RH, Pryor DB, Stack RS, Williams RB, Clapp-Channing NE, Califf RM, Hlatky MA. Effects of coronary angioplasty, coronary bypass surgery medical therapy on employ- ment in patients with coronary artery disease. A prospective comparison study. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:111–117. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-2-199401150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Con AH, Linden W, Thompson JM, Ignaszewski A. The psychology of men and women recovering from coronary artery bypass surgery. J Car-diopulm Rehabil. 1999;19:152–161. doi: 10.1097/00008483-199905000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ayanian JZ, Guadagnoli E, Cleary PD. Physical and psychosocial functioning of women and men after coronary artery bypass surgery. JAMA. 1995;274:1767–1770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schneiderman N, Saab PG, Catellier DJ, Powell LH, DeBusk RF, Williams RB, Carney RM, Raczynski JM, Cowan MJ, Berkman LF, Kaufmann PG, Investigators E. Psychosocial treatment within sex by ethnicity subgroups in the enhancing recovery in coronary heart disease clinical trial. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:475–483. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000133217.96180.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Phillips Bute B, Mathew J, Blumenthal JA, Welsh-Bohmer K, White WD, Mark D, Landolfo K, Newman MF. Female gender is associated with impaired quality of life 1 year after coronary artery bypass surgery. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:944–951. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000097342.24933.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]