Abstract

Introduction

Lupus vulgaris is the most common form of cutaneous tuberculosis. It may easily be overlooked if a proper differential diagnosis is omitted.

Case presentation

A 46-year-old Turkish woman presented with a 42-year history of erythamatous plaque on her left arm. Ziehl–Neelsen and periodic acid-Schiff stains did not show any acid-fast bacilli. Culture from a biopsy specimen was negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The result of a polymerase chain reaction-based assay for Mycobacterium was negative. Histopathologic findings revealed a tuberculoid granuloma containing epithelioid cells, lymphocytes and Langerhans-type giant cells. A diagnosis of lupus vulgaris was made by clinical and histopathologic findings.

Conclusions

The lesion improved after antituberculous therapy, confirming the diagnosis of lupus vulgaris.

Introduction

Lupus vulgaris (LV) is the most common clinical type of cutaneous tuberculosis (TB) in adults [1, 2]. LV commonly appears on the face [3, 4]. LV may rarely be seen on the extremities [5]. The course of LV may continue for years, if it is left untreated [6]. Here, we report the case of a patient with long-lasting LV mimicking hemangioma.

Case presentation

A 46-year-old Turkish woman presented to our institute with a red, well-demarcated plaque on her left arm. She said the lesion had appeared when she was 4 years old. A doctor who our patient had visited when the lesion first appeared had said that the lesion was a birthmark. After that, our patient did not see any doctor with regard to this lesion. However, over the last 2 years, the lesion had started to enlarge, and she consulted a doctor again; this time she was told that it was a harmless vascular lesion, described as a hemangioma.

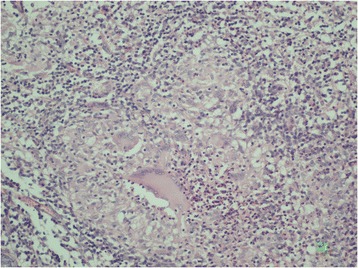

A dermatological examination revealed an erythematous, nontender, 5×7cm in size, well-defined plaque present over the medial part of her left arm. Some erythematous satellite papules, 0.5×1cm in size were scattered around the main lesion (Fig. 1). The lesion did appear to resemble a hemangioma at first sight. Diascopy of the lesions revealed an apple-jelly appearance. There was no lymphadenopathy. A systemic examination was normal. No bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) scar was visible. An incisional biopsy of the plaques showed the formation of a tuberculoid granuloma composed of epithelioid cells, lymphocytes, and Langerhans-like giant cells located in the upper dermis (Fig. 2). A Mantoux test was positive with an induration of 6mm after 48 hours.

Fig. 1.

Erythematous, nontender, well-defined plaque and satellite papules present over the left medial arm

Fig. 2.

Granulomatous infiltration in the dermis with lymphocytes and Langerhans-like giant cells (hematoxylin and eosin original magnification ×100)

Laboratory tests showed a normal blood count. Sputum, stool and urine cultures were negative. The results of venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) tests were negative. Fungal and standard bacterial cultures from the skin biopsy were negative. Ziehl-Neelsen and periodic acid-Schiff stains did not show any acid-fast bacilli. Culture from the biopsy specimen was negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. A real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assay of the biopsy specimen gave a negative result for Mycobacterium. Chest radiography and an abdominal ultrasound did not show any pathologic finding. Underlying bone and joint disease was excluded by radiography. Lupus vulgaris was diagnosed in our patient on the basis of the clinical and histopathologic findings.

Our patient was treated with isoniazid (5mg/kg), rifampin (10mg/kg), ethambutol (25mg/kg), and pyrazinamide (15mg/kg) daily for 2 months, followed by isoniazid and rifampin for 7 months. The cutaneous lesions started to regress within 3 months and had completely healed with atrophic scarring and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation after 9 months (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Atrophy and postinflammatory pigmentation after the treatment

Discussion

Lupus vulgaris is generally regarded as a benign, chronic and progressive form of cutaneous tuberculosis that may be associated with tuberculosis of other organs. LV usually originates from an endogenous source of tuberculosis and is spread hematogenously, lymphatically, or by contagious extension [1, 7]. Less commonly, it is acquired exogenously following primary inoculation tuberculosis or BCG vaccination [8]. No endogenous source for tuberculosis was found, so we concluded that primary inoculation was the case for this patient.

LV is characterized by a macule or papule, with a brownish-red color and soft consistency that form larger plaques by peripheral enlargement and coalescence [2, 9].

The lesions of LV are usually located on the head and neck area [1, 3, 10]. LV is rarely seen on arms and legs; those located on the extremities usually occur by reinoculation [2].

Diagnosing LV may be a formidable task. Various diagnostic methods, including culture, Ziehl–Neelsen staining and PCR may be negative in LV, because of the scarcity of the bacilli within the lesional tissue [11, 12]. In conclusion, the diagnosis usually relies on typical clinical and histologic findings, a positive purified protein derivative (PPD) test and a favorable response to antituberculous therapy [1, 13]. In our patient, the diagnosis of LV was based on typical clinical and histologic findings and excellent response to specific antituberculous therapy. The diagnosis of cutaneous tuberculosis is easily made if one considers it in the differential diagnosis, particularly in those patients with a history of tuberculosis and a suggestive clinical presentation; otherwise, it is easily missed.

The differential diagnosis for our patient included sarcoidosis, other cutaneous tuberculosis types such as tuberculosis cutis verrucosa, scrofuloderma, metastatic tuberculous abscess, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, leishmaniasis, pseudolymphoma and hemangioma.

Conclusions

Tuberculosis is still an important problem in underdeveloped and developing countries due to the poor hygiene conditions and low socioeconomic level. Physicians need to be aware of the diagnosis and treatment of lupus vulgaris and other forms of cutaneous tuberculosis.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the team of the Dermatology Department of Sakarya University. All the authors work in a public hospital. We thank Can Yaldiz, who participated in the English translation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- BCG

bacille Calmette-Guérin

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- LV

lupus vulgaris

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PPD

purified protein derivative

- TB

tuberculosis

- VDRL

venereal disease research laboratory

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

MY conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination and drafted the manuscript. FHD carried out the immunoassays. BSD participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. TE conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Mahizer Yaldız, Phone: +902642957276, Email: drmahizer@gmail.com.

Teoman Erdem, Email: mterdem@hotmail.com.

Bahar Sevimli Dikicier, Email: bsevimlidikicier@gmail.com.

Fatma Hüsniye Dilek, Email: fhdilek@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Barbagallo J, Tager P, Ingleton R, Hirsch RJ, Weinberg JM. Cutaneous tuberculusis, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:319–28. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200203050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bravo FG, Gotuzzo E. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas S, Suhas S, Pai KM, Raghu AR. Lupus vulgaris-report of a case with facial involvement. Br Dent J. 2005;198:135–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raksoy N, Hekim E. Comparative analysis of the clinicopathological features in a cutaneous leishmaniasis and lupus vulgaris in Turkey. Trop Med Parasitol. 1993;44:37–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Senol M, Ozcan A, Mizrak B, Turgut AC, Karaca S, Kocer H. A case of lupus vulgaris with unusual location. J Dermatol. 2003;30:566–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2003.tb00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woo PN, Batta K, Tan CY, Colloby P. Lupus vulgaris diagnosed after 87 years presenting as an ulcerated ‘birthmark’. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:525–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.46332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farina MC, Gegundez MI, Pique E, Esteban J, Martín L, Requena L, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:433–40. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)91389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selimoğlu MA, Erdem T, Parlak M, Eşrefoğlu M. Lupus vulgaris secondary to single BCG vaccination: a case report. Turkish J Pediatr. 1998;40:467–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramesh V, Misra RS, Beena KR, Mukherjee A. A study of cutaneous tuberculosis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:264–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.1999.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aliağaoğlu C, Atasoy M, Sezer E, Aktas A, Ozdemir S. Delayed diagnosis of a bilaterally involved lupus vulgaris casein neck region. Turkiye Klinikleri J Dermatol. 2004;14:100–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sehgal V. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:645–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aliağaoğlu C, Atasoy M, Güleç AI. Lupus vulgaris: 30 years of experience from eastern Turkey. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.İnönü H, Sezer E, Doruk S, Koseoglu D. Cutaneous tuberculosis: report of three lupus vulgaris cases: original image. Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Sci. 2009;29:788–91. [Google Scholar]