Abstract

Chronic inflammation underlies the pathological progression of various diseases, and thus many efforts have been made to quantitatively evaluate the inflammatory status of the diseases. In this study, we generated a highly sensitive inflammation-monitoring mouse system using a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone containing extended flanking sequences of the human interleukin 6 gene (hIL6) locus, in which the luciferase (Luc) reporter gene is integrated (hIL6-BAC-Luc). We successfully monitored lipopolysaccharide-induced systemic inflammation in various tissues of the hIL6-BAC-Luc mice using an in vivo bioluminescence imaging system. When two chronic inflammatory disease models, i.e., a genetic model of atopic dermatitis and a model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), were applied to the hIL6-BAC-Luc mice, luciferase bioluminescence was specifically detected in the atopic skin lesion and central nervous system, respectively. Moreover, the Luc activities correlated well with the disease severity. Nrf2 is a master transcription factor that regulates antioxidative and detoxification enzyme genes. Upon EAE induction, the Nrf2-deficient mice crossed with the hIL6-BAC-Luc mice exhibited enhanced neurological symptoms concomitantly with robust luciferase luminescence in the neuronal tissue. Thus, whole-body in vivo monitoring using the hIL6-BAC-Luc transgenic system (WIM-6 system) provides a new and powerful diagnostic tool for real-time in vivo monitoring of inflammatory status in multiple different disease models.

INTRODUCTION

Exposure to environmental xenobiotics and the accompanying production of cellular oxidative stress give rise to a wide variety of inflammatory diseases in modern society (reviewed in references 1 and 2). To take a step against the widespread prevalence of inflammation-related diseases or low-grade systemic inflammations, it is crucial to elucidate the mechanistic basis for the cellular response to the inflammation. In this aspect, development of an in vivo monitoring system for evaluation of inflammatory status and validation of therapeutic agents has been eagerly awaited. Accurate and sensitive inflammation-monitoring animal models will accelerate further study of inflammatory diseases and development of new therapeutics.

Inflammatory stimuli induce gene expression of a series of proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), and IL-6. Among the proinflammatory cytokines, IL-6 is a key cytokine that is produced by many types of cells, including immune cells (e.g., macrophages and T and B lymphocytes), hepatocytes, glial cells, and fibroblasts (reviewed in reference 3). Expression of IL-6 in resting immune cells is usually suppressed, while it is rapidly induced upon exposure to a variety of inflammatory stimuli (reviewed in reference 4). Subsequently, the induced IL-6 participates in multiple physiological and pathological processes, including innate and acquired immune responses and pathogenesis of autoimmune inflammatory diseases. This sensitive responsiveness of IL6 expression to inflammatory stimuli renders IL-6 a reliable inflammatory marker. The intimate involvement of IL-6 in inflammatory diseases has been instrumental in promoting the development of IL-6-related therapeutic agents against inflammatory diseases (reviewed in reference 5).

Atopic dermatitis, which affects almost 20% of people in countries with high prevalence, has been a global public health concern (6). We recently generated a transgenic mouse line which serves as an atopic dermatitis model by forcibly expressing a constitutively active (CA) form of arylhydrocarbon receptor (AhR) in skin keratinocytes under the regulation of the keratin-14 (K14) gene regulatory region (7). This line of mice has been referred to as AhR-CA mice. AhR is known to be a ligand-activated transcription factor that mediates the toxicity of a various environmental pollutants, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) (reviewed in references 8 and 9). PAHs are ranked a top risk factor for pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis (10), and we found that AhR-CA mice serve as a reliable model of pollution-induced atopic dermatitis (7).

It has also been known that multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) which affects approximately 2.5 million people globally (11). The experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) mouse model has been developed as an excellent animal model of MS which mimics the pathological process of autoimmune demyelination (12). Cellular oxidative stress appears to contribute to the acceleration of demyelination in the EAE model (13), suggesting that key therapeutic targets for MS may reside in or link to the antioxidative stress response system.

Transcription factor Nrf2 plays important roles in cellular responses to oxidative stresses (14, 15, 16). Upon exposure to oxidative stresses, Nrf2 accumulates in the cellular nucleus and dimerizes with one of the small Maf (sMaf) proteins. Subsequently, the Nrf2-sMaf heterodimer binds to the antioxidant-responsive element/electrophile-responsive element (ARE/EpRE) and induces expression of a battery of antioxidant and detoxifying enzymes (14, 15, 16). The antioxidant and detoxifying enzymes contribute to the cellular protection against oxidative and xenobiotic insults. In agreement with this concept, a series of studies have revealed that Nrf2 plays an anti-inflammatory role in vivo. For instance, Nrf2-deficient mice showed persistent inflammation in a carrageenan-induced acute pleurisy model (17) and in elastase-induced pulmonary inflammation (18). Moreover, we found that older Nrf2-deficient mice more often developed chronic inflammatory disease, such as severe autoimmune glomerulonephritis, than did control mice (19).

Of note, a recent report suggests that Nrf2 exerts preventive activity against the pathogenic process in EAE model mice (13). However, evaluation of EAE depends solely on a scoring system that reflects neuronal symptoms. Correlations between the appearance of the neuronal phenotype and the onset of inflammations have been largely unidentified. In order to monitor the aseptic inflammation within the central nervous system (CNS), precise quantitative evaluation of the inflammatory status of EAE during the disease course is critically needed. This type of monitoring is particularly important to elucidate the precise function of Nrf2 in prevention or remission of degenerative neural diseases.

To establish a reliable inflammation-monitoring system, we decided to challenge a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC)-based reporter transgenic mouse system in this study. Our choice here is the in vivo monitoring system using the human IL-6 gene (hIL6) and firefly luciferase. We have generated BAC-based hIL6-luciferase (hIL6-BAC-Luc) reporter transgenic mice and subjected them to the inflammatory disease models. We found in real-time in vivo monitoring of disease status that these lines of mice express luciferase luminescence under the influences of extended hIL6 regulatory sequences. Our present study demonstrated that whole-body in vivo monitoring using the hIL6-BAC-Luc (referred to here as WIM-6) transgenic system provides a unique, noninvasive, and quantitative diagnostic means to evaluate the progression and/or severity of inflammatory diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

BAC modification and generation of transgenic mice.

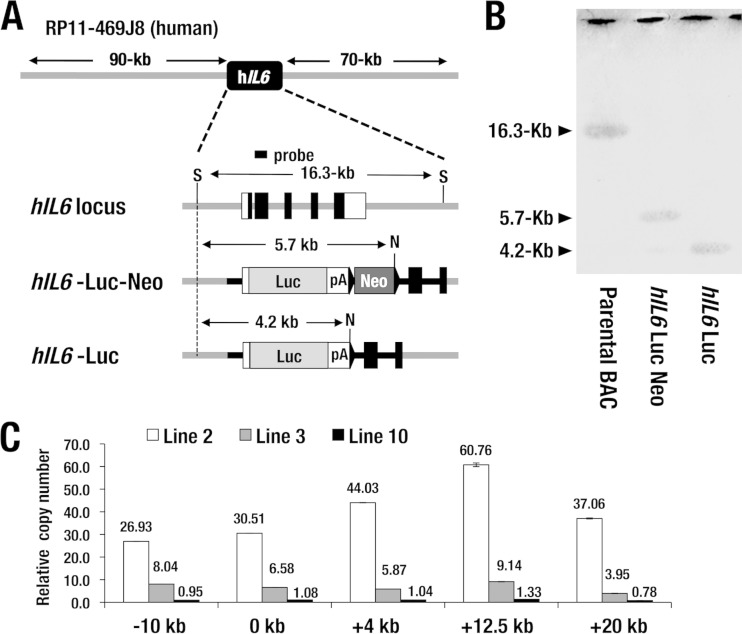

We utilized a 176-kb BAC clone, RP11-469J8, which harbors hIL6 in the center region, and integrated a firefly luciferase gene into the locus by homologous recombination. The resulting clone is referred to here as the hIL6-BAC-Luc clone, and transgenic mice were generated utilizing the BAC clone. The 5′ homologous region of the targeting vector contains a 1.1-kb 5′-flanking region of hIL6, while the 3′ homologous region includes 1.7-kb sequences 3′ from the translation initiation site (Fig. 1A). The luciferase cassette was derived from pGL3-basic vector (Promega). These fragments were cloned into a vector containing a neomycin resistance gene (neo) cassette to generate a targeting construct. Homologous recombination was conducted within Escherichia coli as described previously (20). Using this hIL6-BAC-Luc construct, three independent lines of transgenic mice (lines 2, 3, and 10) were generated.

FIG 1.

Generation of hIL6-BAC-Luc transgenic (WIM-6) mouse. (A) Structure of BAC clone RP11-469J8 containing approximately 90-kb 5′- and 70-kb 3′-flanking sequences of hIL6 locus. The targeting strategy for the hIL6-BAC-Luc reporter is depicted. pA, simian virus 40 (SV40) late poly(A) signal; S, SacI; N, NotI. The neomycin resistance cassette is deleted by arabinose-induced FLP recombinase activity in the EL250 E. coli bacterial strain. (B) Southern blot analysis of the parental BAC (RP11-469J8), hIL6-Luc-Neo, and hIL6-Luc constructs using the hIL6 coding sequence probe as indicated for panel A. A 16.3-kb band (parental BAC), a 5.7-kb band (hIL6-Luc-Neo), and a 4.2-kb band (hIL6-Luc) generated by the double digestion with SacI and NotI are indicated by arrowheads. DNA restriction fragments corresponding to each band are depicted by arrows in panel A. (C) Copy number analysis at five points relative to the translation initiation site of the hIL6-BAC-Luc transgene. Line 2 mice incorporate approximately 26 to 60 stably integrated transgene copies. Line 3 mice harbor 3 to 8 copies, while line 10 mice carry 1 copy of the hIL6-BAC-Luc transgene. Data represent means ± standard deviations (SD) of the results from three mice of each line.

The copy number and integrity of the transgene were determined by genomic quantitative PCR as previously described (21). Primers used for genomic quantitative PCR are listed in Table 1. We also utilized an Nrf2-deficient line of mice (14) and an AhR-CA line of transgenic mice (7) in this study. Endotoxin shock was induced in 2- to-4-month-old hIL6-BAC-Luc mice by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma-Aldrich) at a dosage of 1 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg of body weight.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of sense and antisense primers used in quantitative genomic PCR, RT-qPCR, and genotypinga

| Assay | Gene | Sense primer | Antisense primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| RT-qPCR | mIL6 | CTGCAAGAGACTTCCATCCAG | AGTGGTATAGACAGGTCTGTTGG |

| mIL1α | GCACCTTACACCTACCAGAGT | AAACTTCTGCCTGACGAGCTT | |

| mIL1β | TGTAATGAAAGACGGCACACC | TCTTCTTTGGGTATTGCTTGG | |

| luciferase | ACGATTTTGTGCCAGAGTCC | AGAATCTCACGCAGGCAGTT | |

| Gapdh | GTCGTGGAGTCTACTGGTGTCTT | GAGATGATGACCCTTTTGGC | |

| CD45 | TCATGGTCACACGATGTGAAGA | AGCCCGAGTGCCTTCCT | |

| Genomic qPCR | −10-kb hIL6 | AGGCACAGGGAATTGAAGTG | TGGTTTAAATCCCAGCTCCA |

| 0-kb hIL6 | TACCCCCAGGAGAAGATTCC | GCCTACCCACCTCCTTTCTC | |

| +4-kb IL6 | GGGAGACAGAACAGCAAAGG | CTCAAATGATCCACCCACCT | |

| +12.5-kb IL6 | ACATGACAAGGATGCCCACT | CTTTTCAGGAATGCCCTTCA | |

| +20-kb IL6 | AATTTCAGCTTTGGGTGCTG | CCTCTACCTTCCCAGGACAA | |

| G2-2.8 | GCCCTGTACAACCCCATTCTC | TTGTTCCCGGCGAAGATAAT |

qPCR, quantitative PCR.

All mice were handled according to the regulations of the Standards for Human Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Tohoku University and the Guidelines for Proper Conduct of Animal Experiments from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan.

Imaging of luciferase activity in vivo and ex vivo.

In vivo bioluminescence imaging was conducted utilizing an in vivo imaging system (IVIS) (PerkinElmer) as previously described (22). Briefly, hIL6-BAC-Luc transgenic mice were injected intraperitoneally with 75 mg/kg d-luciferin. Ten minutes after the luciferin injection, the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane. Subsequently, the mice were placed in a light-sealed chamber and the luciferase activity was imaged for 5 to 10 s. Photons emitted from various regions of mouse were quantified with Living Image software (PerkinElmer). IVIS spectrum computed tomography (IVIS-CT) was conducted according to the manufacturer's instruction. Ex vivo imaging was performed by incubating the organs or tissue samples with 300-μg/ml d-luciferin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Each organ or tissue was isolated from the hIL6-BAC-Luc mice euthanized immediately after the administration of d-luciferin.

EAE induction.

EAE was induced basically as described previously (23). Briefly, mice were subjected to subcutaneous injection of myelin/oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG; 150 μg) peptide (amino acids 35 to 55)–0.1 ml of complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) emulsion containing 400 μg of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Difco) on day 0. Subsequently, the mice received intraperitoneal injection of 200 ng of pertussis toxin (List Biological Laboratories) on days 0 and 2. Disease states of EAE were assessed and given the following scores: 0, no sign of disease; 1, limp tail or hind limb weakness; 2, partial hind limb paralysis; 3, complete hind limb paralysis (23).

Histological examination.

Each tissue was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight and then processed for immunostaining as frozen or paraffin sections. For immunofluorescence analysis, anti-F4/80 (Abcam; ab6640), anti-Gr-1 (Abcam; ab2557), and anti-firefly luciferase (Abcam; ab21176) antibodies were used. Fluorescence was observed by the use of an LSM510 confocal imaging system (Carl Zeiss). Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining and luxol fast blue staining were performed using a standard protocol. The thickness of the epidermal layer and the number of infiltrating cells were measured in four contiguous skin sections from three mice of each genotype.

BMDMs.

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were generated as described previously (24). Briefly, bone marrow mononuclear cells of 8- to-12-week-old hIL6-BAC-Luc mice were isolated and the cells were cultured in the presence of 20 ng/ml macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF; Wako) for up to 7 days. At day 3, fresh M-CSF was added. At day 7, more than 90% of the cells were differentiated into CD11b-positive macrophages. Cells were incubated with 5 ng/ml LPS for the times indicated in Fig. 2, 3, and 5 and subjected to a luciferase assay. For the luciferase assay, cells were lysed in passive lysis buffer (Promega), and 20 μl of the lysate was assayed for luciferase enzyme activity on a Lumat LB 9507 tube luminometer (Berthold Technologies).

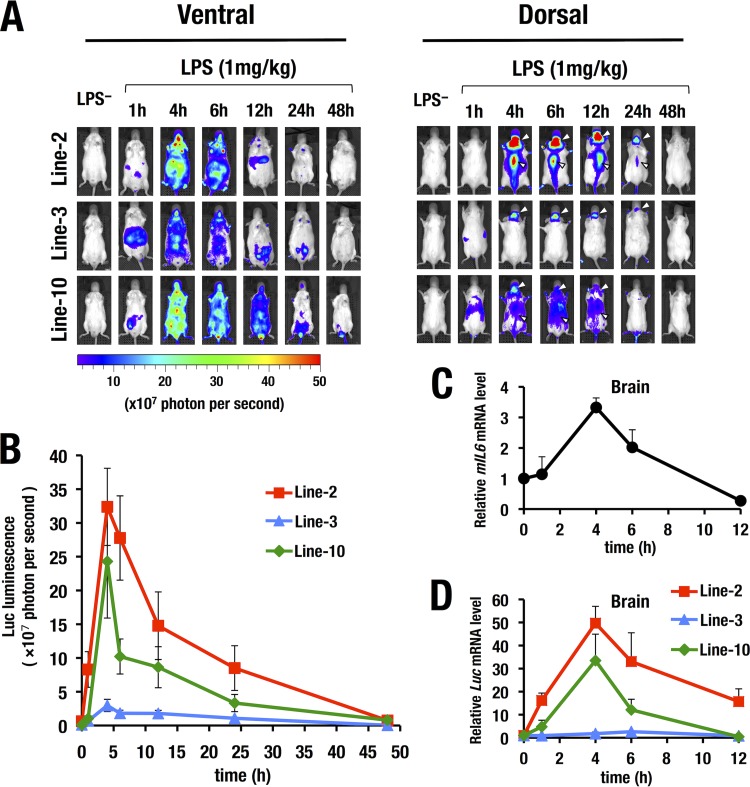

FIG 2.

Time course analysis of the LPS-induced Luc bioluminescence by the WIM-6 system. (A) All three lines of WIM-6 mice exhibited robust LPS-induced luciferase luminescence in the ventral and dorsal views at 1 to 48 h after the LPS administration. (B) Quantitative analysis of luciferase luminescence from the dorsal view at multiple time points up to 48 h after LPS administration. Luciferase luminescence was increased by 4 h after LPS administration. Thereafter, the luminescence level gradually decreased to the baseline level by 48 h after the LPS administration. (C) Expression level of endogenous IL6 mRNA after LPS administration (n = 9). (D) Expression level of luciferase mRNA in brain after LPS administration. Note that the induced luciferase mRNA expression is correlated with the luminescence level in each line of WIM-6 mice. Data represent means ± SD of the results from three mice of each line.

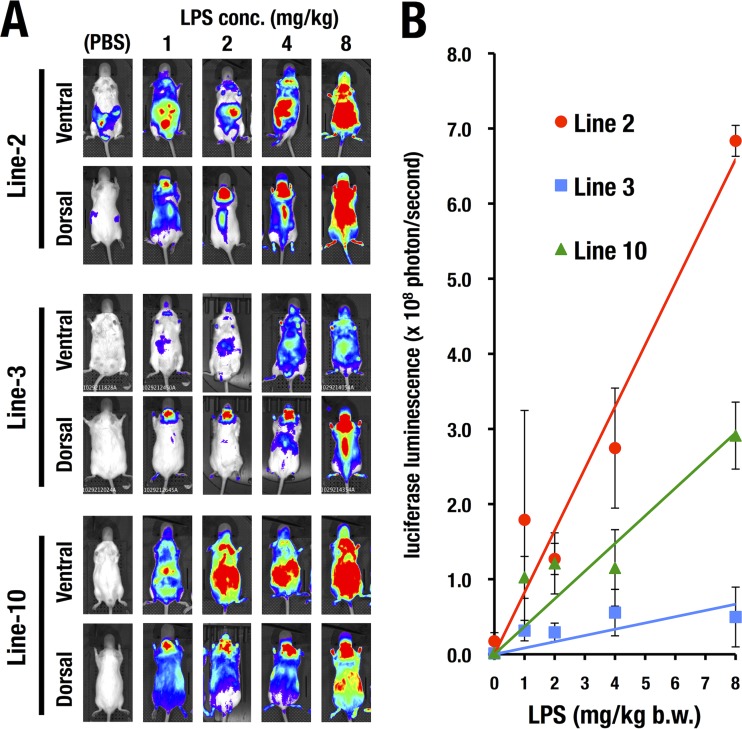

FIG 3.

LPS dose-dependent induction of luciferase luminescence detected by the WIM-6 system. (A) All three lines of WIM-6 mice exhibited LPS dosage-dependent (0 to 8 mg/kg) luciferase luminescence in both the ventral view and the dorsal view at 4 h after the LPS administration. conc., concentration. (B) Quantification data of luminescence-positive areas in the WIM-6 mice treated with 0 (PBS), 1, 2, 4, or 8 mg/kg of LPS (ventral view). Note that the line 2 mice (the high-copy-number line) show the steepest slope for the dose-response relationship. The line 3 mice (medium-copy-number line) and the line 10 mice (low-copy-number line) show lower levels of luminescence than the line 2 mice. Data are presented as means ± SD of the results from three WIM-6 mice treated with each concentration of LPS. mg/kg b.w., milligrams per kilogram of body weight.

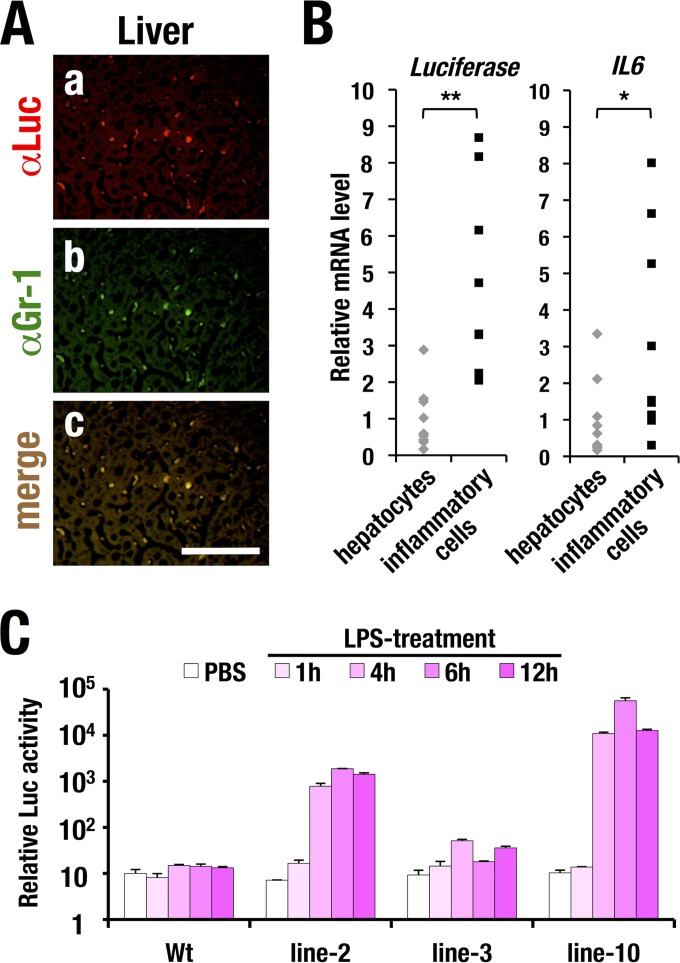

FIG 5.

LPS-induced luciferase expression in inflammatory cells. (A) Immunohistochemical analysis of luciferase (a) and Gr-1 (b) in liver sections from LPS-treated WIM-6 transgenic mice. A merged image (c) is also shown. Bars, 100 μm. (B) luciferase (left) and mouse IL6 (right) mRNA expression levels in Gr-1- and CD11b-positive inflammatory cells and hepatocytes prepared from LPS-treated WIM-6 mice (n = 9; line 10). Values are normalized to the Gapdh level. Statistically significant differences are indicated (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; Student paired t test). (C) LPS-induced luciferase luminescence in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) from each line of the WIM-6 transgenic mouse. Note that the LPS treatment (5 ng/ml) induces robust luciferase activity at 4 to 6 h after LPS treatment in the BMDMs from the line 2 and line 10 WIM-6 mice, while the results from the line 3 mice show a low level of luciferase induction. Wt, wild type.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted by the use of Isogen (Nippon Gene). cDNA was synthesized by the use of SuperScript III (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was performed with ABI 7300 and SYBR green master mix (Nippon Gene). The mRNA expression level was normalized to the GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) expression level. Separation of Gr-1- and CD11b-positive inflammatory cells from a single-cell suspension of mouse liver was conducted using a FACSAria sorter (BD Bioscience), as previously described (25). Primers used in real-time RT-PCR are listed in Table 1.

RESULTS

Generation of the hIL6-BAC-Luc transgenic (WIM-6) mice.

To generate mice for inflammation monitoring, we exploited a BAC transgenic mouse system. We employed BAC clone RP11-469J8, which contains an hIL6 locus with approximately 90-kb 5′ and 70-kb 3′ flanking sequences (Fig. 1A). We introduced a luciferase (Luc) reporter gene into the first exon of hIL6 by means of homologous recombination in E. coli strain EL250 (20). After the BAC recombination, the neomycin resistance cassette was deleted by arabinose-induced FLP (flippase) recombinase activity. Successful recombination was confirmed by Southern blotting (Fig. 1B). Purified BAC DNA was injected into fertilized BDF1 ova, and three independent lines of WIM-6 mice (lines 2, 3, and 10) were generated (Fig. 1C). After breeding the three established lines of WIM-6 mice in the ICR/CD1 background for more than five generations, we examined transgene copy numbers in each BAC transgenic line. To this end, we conducted genomic quantitative PCR analysis at 5 different genomic regions located within the flanking sequences of hIL6. We found that line 2 incorporates approximately 26 to 60 stably integrated transgene copies in all 5 regions examined. Line 3 harbors 3 to 8 copies of the hIL6-BAC-Luc transgene, while line 10 carries only 1 copy.

Monitoring of LPS-induced sepsis model by WIM-6 system.

We next conducted intraperitoneal administration of LPS (1 mg/kg) as an inducer of inflammatory cytokines and monitored inflammatory status utilizing the WIM-6 system. We quantitatively analyzed the luciferase luminescence by the use of an in vivo imaging system (IVIS) at multiple time points from 1 h to 48 h after the LPS treatment and examined the natural course of the LPS-induced sepsis (Fig. 2A). We found that all three lines of WIM-6 mice exhibited luciferase luminescence in both the ventral and dorsal sides from 1 h after the LPS administration onward. Subsequently, the LPS-induced luciferase luminescence expanded throughout the body. The luminescence intensity reached the maximum level by 4 to 6 h after the LPS administration and thereafter gradually decreased to the baseline level by 48 h after the treatment (Fig. 2B). Quantification of luciferase luminescence demonstrated that the line 2 (high-copy-number) mice and line 10 (low-copy-number) mice showed high to medium levels of luciferase luminescence upon LPS treatment (Fig. 2B). The level of luminescence of the line 3 (medium-copy-number) mice was much lower than that of the mice of lines 2 and 10 (Fig. 2A and B).

LPS-induced IL6 expression in brain.

We noticed that all three lines of WIM-6 mice showed robust luciferase activity in the central nervous system (CNS), including the brain and the spinal cord region, upon LPS treatment (dorsal views in Fig. 2A). This result is in very good agreement with the finding that IL-6 is a major cytokine in the CNS and is produced from both glial and neuronal cells in response to neuronal injury (26). To clarify whether the transgenic luciferase expression recapitulates the time course of induced endogenous IL6 expression in the brain, we examined expression of IL6 and luciferase mRNAs in the brain from three lines of WIM-6 mice at multiple time points after the LPS administration. We found that IL6 mRNA expression was highly induced at 4 h after the LPS treatment and that the expression level thereafter was gradually decreased (Fig. 2C). Showing very good agreement, the luciferase mRNA level reached its peak at 4 to 6 h in all three lines of the WIM-6 mice (Fig. 2D). The induced luciferase mRNA level in each line of WIM-6 mice correlated well with the whole-mount bioluminescence intensity levels in the respective lines of mice. These results thus demonstrate that all WIM-6 mouse lines consistently recapitulated the time course profile of induced IL6 expression, while the three different lines of WIM-6 mice exhibited graded levels of luciferase reporter expression.

LPS dose-dependent induction of luciferase luminescence in the WIM-6 system.

We next administered incremental doses (1, 2, 4, and 8 mg/kg) of LPS to the WIM-6 mice and examined the dose-response relationship for luciferase luminescence at 4 h after the treatment. Treatment with higher dosages of LPS induced more-robust luciferase luminescence in all three lines of WIM-6 mice (Fig. 3A). Quantitative analysis of the luciferase luminescence at each LPS concentration clearly demonstrated LPS dose-dependent luciferase induction in all three lines of WIM-6 mice (Fig. 3B).

We found that the line 2 (high-copy-number) mice showed the most robust luciferase luminescence upon LPS treatment (Fig. 3B). The line 10 (low-copy-number) mice showed a middle level of luminescence, while the line 3 (medium-copy-number) mice showed the lowest level (Fig. 3B). Since the line 10 mice carrying only one copy of the hIL6-BAC-Luc transgene showed robust luminescence in multiple tissues throughout the body, we mainly exploited the line 10 mice in the subsequent analyses unless otherwise indicated.

The luciferase activity detected in the WIM-6 system recapitulates the tissue distribution of the endogenous murine IL6 (mIL6) expression.

To clearly assess the tissue distribution of luciferase luminescence detected in the WIM-6 system, we surgically exposed internal organs of the LPS-treated mice and subjected those mice to IVIS analysis (Fig. 4A). Upon LPS treatment, the vast majority of tissues in the WIM-6 mice showed luciferase luminescence to various degrees. In particular, the liver exhibited a strong signal among the various tissues (arrowhead in Fig. 4A). We dissected multiple different tissues, including brain, thymus, lung, liver, adipose tissue, kidney, and skin, at 4 h after the LPS administration and subjected them to ex vivo imaging analysis (Fig. 4B). We found that almost all the tissue samples showed LPS-induced robust luciferase luminescence (Fig. 4B). Quantitative analysis of the luciferase luminescence demonstrated several-hundred-fold induction after the LPS treatment (Fig. 4C).

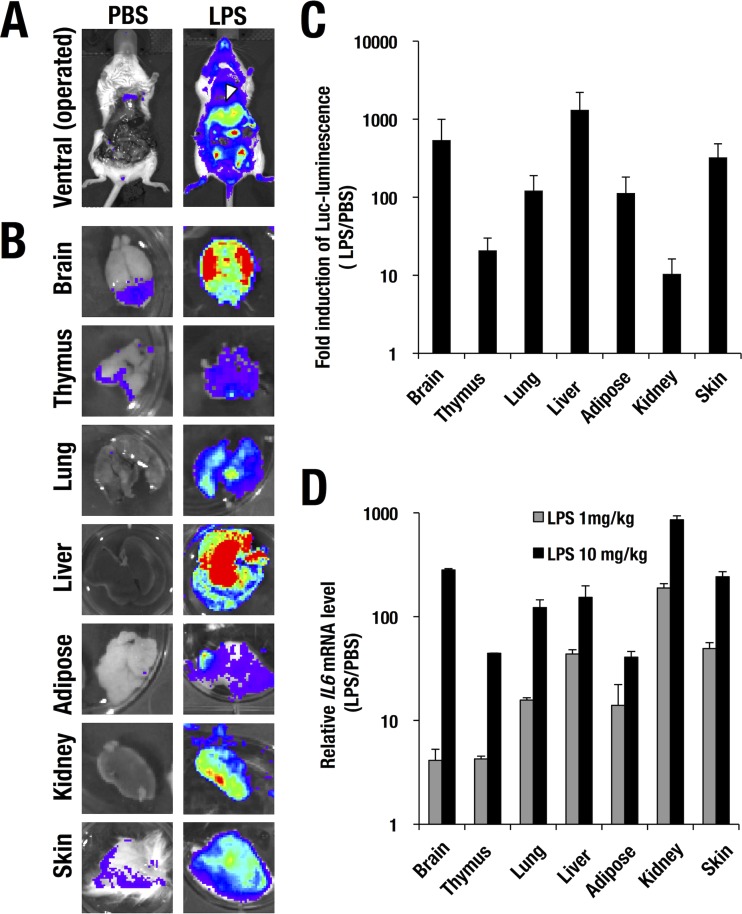

FIG 4.

LPS-induced luciferase reporter luminescence directed by the WIM-6 system in each tissue. (A and B) LPS-induced luciferase luminescence in hIL6-BAC-Luc mice subjected to abdominal operations (A) and in each dissected tissue sample (B) examined by an in vivo imaging system. (C) Fold induction of LPS (10 mg/kg)-induced luciferase luminescence relative to PBS treatment (LPS/PBS) in each tissue. (D) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of endogenous mouse IL6 mRNA expression normalized to the Gapdh level. Data are presented as means ± SD of the results from the three WIM-6 mice treated with each concentration of LPS (1 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg).

We next examined the mRNA expression level of the endogenous IL6 in each tissue. Upon LPS treatment, IL6 expression was dramatically induced up to 100-fold or more in most of the tissues in an LPS dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4D). Notably, the profile of induced expression of the hIL6-BAC-directed luciferase luminescence represented well the induced IL6 mRNA expression pattern (Fig. 4D). In particular, the brain, lung, liver, and kidney showed highly induced expression of the endogenous IL6 (Fig. 4D), which correlated well with the induced expression pattern of the luciferase luminescence. These data thus demonstrate that the WIM-6 system faithfully recapitulates the endogenous IL6 expression profile in vivo.

The luciferase reporter is predominantly expressed in infiltrating inflammatory cells.

It has been shown that a major source of IL-6 secretion in liver under the LPS-induced septic condition is infiltrating granulocytes and macrophages (reviewed in references 27 and 28). To clarify whether the luciferase reporter expression recapitulates the endogenous IL6 expression in granulomacrophages, we conducted immunohistochemical analyses using anti-luciferase antibody on liver sections after LPS treatment. We found that the luciferase immunoreactivity was predominantly detected in infiltrating inflammatory cells in the hepatic sinusoidal space (Fig. 5A, panel a). Most of the luciferase-positive cells were also positively stained by anti-Gr-1 antibody, a granulomacrophage marker (Fig. 5A, panels b and c). These results support the notion that upon LPS treatment, expression of the hIL6-BAC-directed luciferase reporter is predominantly induced in the infiltrating inflammatory cells in liver, which are mainly composed of granulomacrophages.

To further address the inflammatory cell-preferred luciferase expression in the liver, we separated the Gr-1- and CD11b-positive inflammatory cells from single-cell suspensions of the liver cells in the LPS-treated WIM-6 mice and assessed the expression levels of the luciferase and endogenous IL6 mRNAs. The luciferase mRNA was expressed more abundantly in the inflammatory cells than in the hepatocytes (left panel in Fig. 5B). Consistently, endogenous IL6 transcripts were predominantly detected in the inflammatory cells in comparison to the hepatocytes (right panel in Fig. 5B). These results further support the notion of inflammatory cell-directed expression of the luciferase reporter in the WIM-6 mice treated with LPS.

Luciferase activity is induced in BMDMs upon LPS stimulation.

To further address luciferase activity in the IL-6-producing cells, we developed BMDMs and examined the LPS-induced luciferase activity in each line of the WIM-6 mice. It has been reported that BMDMs produce a series of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, upon LPS stimulation (27). Consistently, our results showed that the hIL6-BAC-directed luciferase activity was significantly induced in the BMDMs from 4 to 6 h after LPS treatment onward (Fig. 5C). BMDMs from line 2 mice (high level of expression) and line 10 mice (medium level of expression) showed high-level induction, while the line 3 mice (low level of expression) showed a low-level response. These results demonstrate that the luciferase activity in WIM-6 mice monitors the inflammatory response in the BMDMs.

Monitoring of inflammatory status in an atopic dermatitis model.

We next monitored chronic inflammatory status in AhR-CA mice (7) by using the WIM-6 system. While AhR-CA mice exhibited a normal appearance around the perinatal stage, they developed severe progressive dermatitis from the weaning period onward (Fig. 6A). To evaluate inflammatory status, we crossbred the AhR-CA mice to the WIM-6 mice and examined the luciferase luminescence every other week by means of the IVIS up to 12 weeks after birth. The hIL6-BAC-directed luciferase luminescence was detected in the AhR-CA mice from 4 weeks after birth (Fig. 6B). Thereafter, the luciferase luminescence was progressively increased until 12 weeks after birth, and quantification of the data is shown in Fig. 6C. The robust increase of luciferase activity nicely correlated with the progression of the skin lesion. These data indicate that the WIM-6 system faithfully monitors the skin inflammation associated with the atopic dermatitis of the AhR-CA transgenic mice.

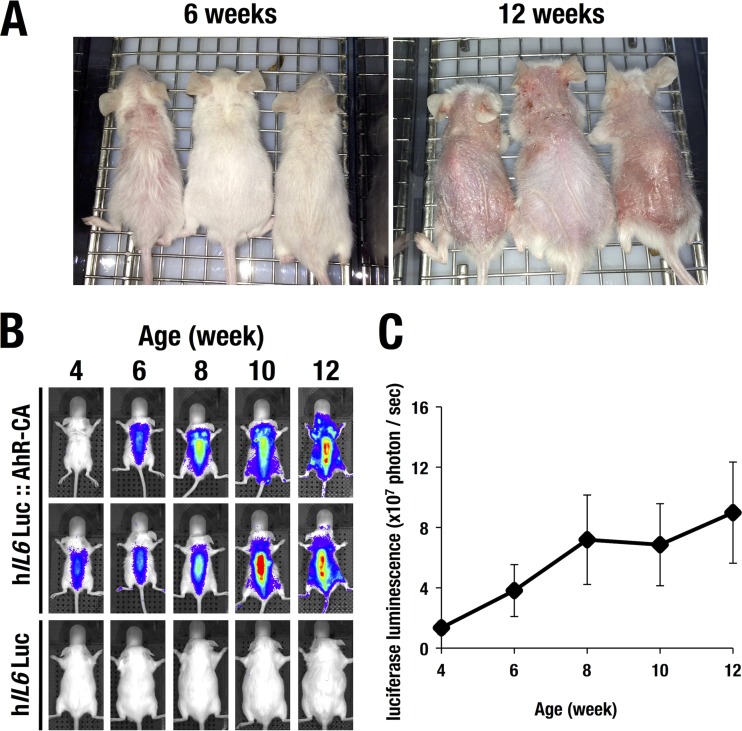

FIG 6.

Progression of skin eczema in the AhR-CA mice. (A) Gross observations of the AhR-CA mice at 6 weeks and 12 weeks of age. Note the time-dependent progression of the eczematous skin lesions. (B) The WIM-6 system detects a robust increase of luciferase luminescence in accordance with the progression of skin eczema in AhR-CA mice. Two hIL6-BAC-Luc::AhR-CA mice and one control hIL6-BAC-Luc mouse are depicted. (C) The luciferase luminescence level in the hIL6-BAC-Luc::AhR-CA mice was increased in a time-dependent manner from 4 weeks after birth onward.

Monitoring of therapeutic efficacy of dexamethasone against the skin lesion in AhR-CA mice.

Key to the management for atopic dermatitis is the introduction of effective anti-inflammatory therapy. As dexamethasone, a classical glucocorticoid receptor agonist, has been used for treatment of chronic skin inflammation (reviewed in reference 29), we attempted monitoring of the therapeutic efficacy of dexamethasone against the atopic dermatitis by using the WIM-6 system. We applied dexamethasone (0.1% [wt/wt])–petrolatum on the back skin of the AhR-CA mice twice a week from 8 weeks after birth. The hIL6-BAC-directed luciferase luminescence on the back skin was quantitatively monitored by IVIS every week (at 8, 9, 10, and 11 weeks). We found that the dexamethasone treatment significantly reduced the hIL6-BAC-directed luciferase luminescence, while, in contrast, AhR-CA mice treated only with petrolatum showed only a minimal reduction in luciferase luminescence (Fig. 7A and B). The skin lesion seen with the AhR-CA mice was characterized by severe hyperkeratosis and robust infiltration of inflammatory cells in comparison with the results seen with the wild-type control mice (left and middle panels in Fig. 7C). Both the thickness of the epidermal layer and the number of infiltrating inflammatory cells were significantly reduced by the dexamethasone treatment (right panels of Fig. 7C and D).

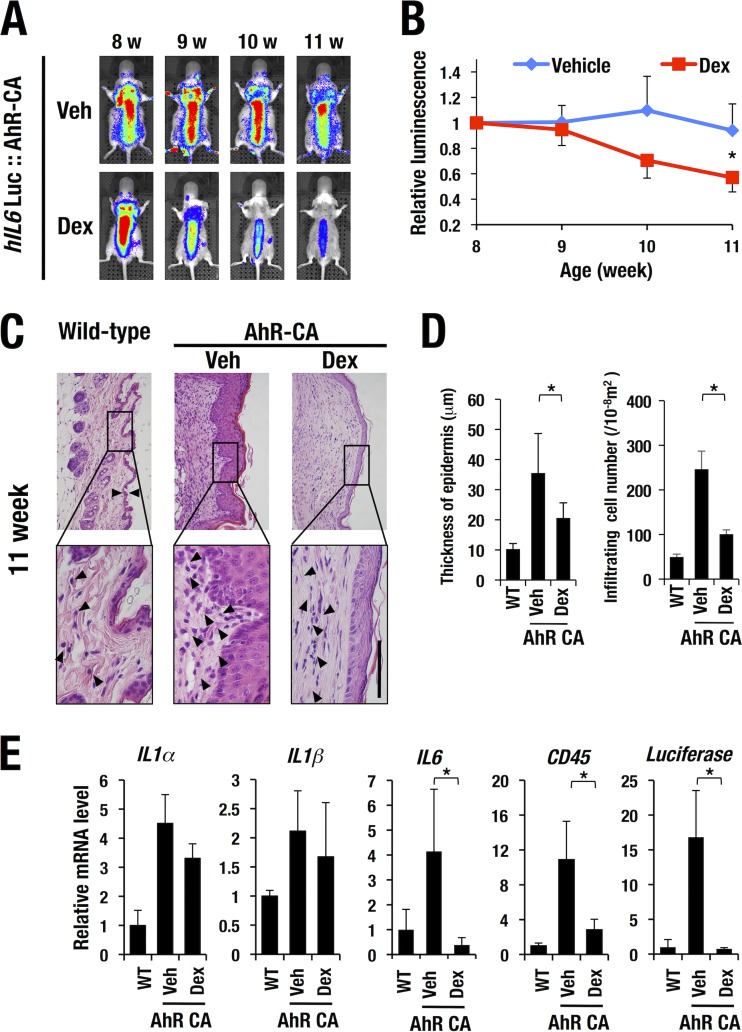

FIG 7.

Monitoring of the disease status of the atopic dermatitis in the AhR-CA mice. (A) The luciferase luminescence in the AhR-CA mice was attenuated upon dexamethasone (Dex) treatment from 8 weeks (w) after birth onward. Vehicle (Veh)-treated control AhR-CA mice persistently showed a high level of luciferase luminescence. (B) Quantification of luciferase luminescence in the vehicle- or dexamethasone-treated mice. Note that the dexamethasone treatment dramatically reduced the luciferase luminescence. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining of skin from wild-type and AhR-CA mice with or without dexamethasone treatment. Note that thickness of the epidermal layer and the number of infiltrating inflammatory cells (arrowheads) in the AhR-CA mice were significantly decreased upon dexamethasone treatment. Bar, 100 μm. The high-magnification images (lower panels) are derived from the rectangles indicated in the low-magnification images (upper panels). (D) Quantification of thickness of epidermal layer and number of infiltrating inflammatory cells. (E) mRNA expression levels of IL1α, IL1β, IL6, CD45, and luciferase in the skin tissues of each genotype of mice. Values are normalized to the Gapdh level. Statistically significant differences are indicated (*, P < 0.05; Student unpaired t test). WT, wild type.

The robust infiltration of inflammatory cells in the petrolatum-treated AhR-CA mice was associated with a dramatic increase in the mRNA levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6) and CD45 (infiltrating leukocyte marker) compared with those in the wild-type control mice (Fig. 7E). Increased expression of luciferase mRNA was also well correlated with the induction of luciferase luminescence in the petrolatum-treated AhR-CA mice, and dexamethasone treatment significantly decreased the mRNA level of CD45, IL-6, and luciferase (Fig. 7E). Although the mRNA expression levels of IL-1α and IL-1β were decreased by the dexamethasone treatment, the difference did not reach the level of statistical significance. These results demonstrate that the WIM-6 system faithfully monitors the therapeutic efficacy of dexamethasone against atopic dermatitis in the AhR-CA transgenic mice.

Monitoring of chronic inflammation accompanied by experimental encephalomyelitis.

Given the robust LPS-induced luciferase luminescence in the CNS of WIM-6 mice, we surmised that the WIM-6 system could be a useful means for the monitoring of inflammatory diseases in the CNS. Therefore, we next evaluated inflammatory status in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a murine model of neuronal autoimmune disease which is well known to closely mimic the inflammatory demyelinating diseases, including multiple sclerosis (12). WIM-6 mice were immunized with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG; amino acids 35 to 55) and monitored daily to assign neurological severity scores of the EAE symptoms (EAE score [23]). By 10 days after the immunization (day 10), 69% of the ICR strain mice exhibited neurological disorders characterized by hypotonus of the tail muscle (Fig. 8A and data not shown). The neurological symptoms progressively deteriorated, and hind limb paralysis was seen by day 20 in the most severe cases. Thereafter, the mice spontaneously started to recover and the EAE scores reflected the improved condition of the mice in most of the cases. Emergence of neurological symptoms was associated with demyelination, which is characterized by the cystic lesions in the white matter of the brain (arrowheads in panels b and e of Fig. 8B), while the control mice administered only complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) rarely showed such cystic changes (panels a and d). The damaged brain showed enhanced infiltration of F4/80-positive macrophages and microglial cells, whereas the control mice showed a low number of infiltrating cells (compare panels g and h of Fig. 8B).

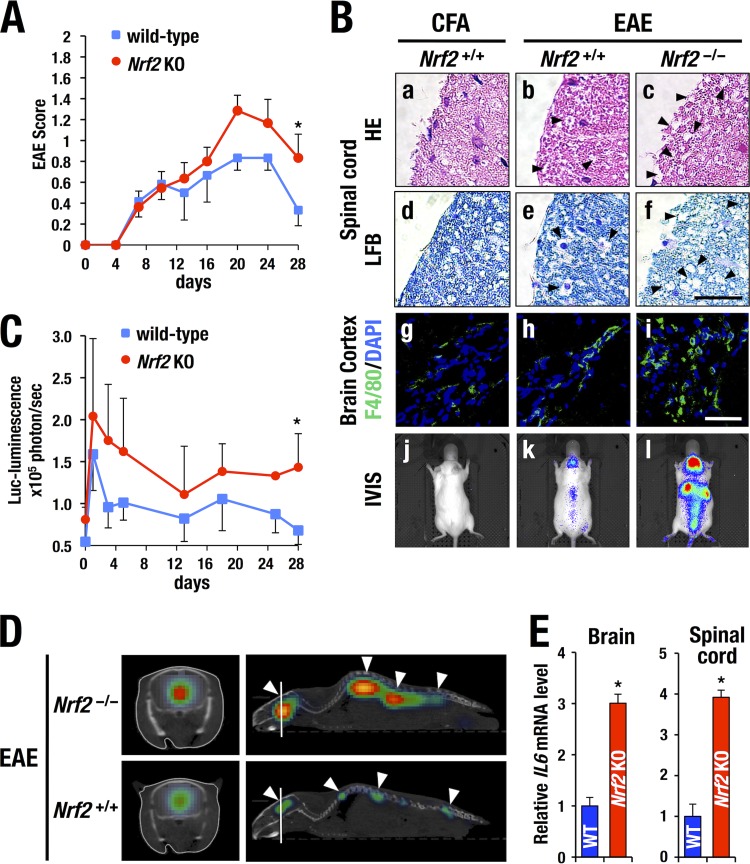

FIG 8.

Monitoring of chronic inflammation status in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model. (A) Progression of EAE scores in wild-type (n = 5) and Nrf2-deficient (knockout [KO]) (n = 5) mice. Data represent averages ± SD. Statistically significant differences are indicated (*, P < 0.05; Student unpaired t test). (B and C) At 14 days after EAE induction, wild-type mice showed cystic lesions in the spinal cord (arrowheads in panels b and e), which is associated with infiltration of F4/80-positive macrophages and microglial cells at a greater abundance than in CFA (complete Freund's adjuvant)-treated control mice (compare panels g and h). Note that Nrf2-deficient mouse exhibited more-robust cyst formation (arrowheads in panels c and f) and a higher number of infiltrating F4/80-positive cells (i) upon EAE induction than did the wild-type mouse. HE, hematoxylin and eosin; LFB, luxol fast blue. Bars, 100 μm. EAE-induced WIM-6 mice show robust bioluminescence in the brain and spinal cord region (k). Control WIM-6 mice administered only CFA showed no bioluminescence (j). Note that the EAE-induced Nrf2-deficient mice exhibited more-robust luciferase bioluminescence than the EAE-induced Nrf2+/+ mice throughout the observation period (l and C). Statistically significant differences are indicated (*, P < 0.05; Student unpaired t test). DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. (D) Robust luciferase luminescence is induced in the brain and spinal cord region of the Nrf2-deficient mice (arrowheads in upper panel) in comparison with the Nrf2+/+ mice (arrowheads in lower panel) at 14 days after EAE induction. Transverse section images (left panels) were generated at the brain level as indicated with the white lines in the sagittal section images (right panels). (E) Expression of IL6 mRNA in brain (left) and spinal cord (right) at 14 days after EAE induction. Note the higher abundance of IL6 transcripts in the Nrf2-deficient EAE mice (n = 5) than in the wild-type EAE mice (n = 5). Statistically significant differences are indicated (*, P < 0.05; Student unpaired t test).

We next monitored the disease status of EAE by the use of the WIM-6 system. We found that the luciferase luminescence was sharply increased in the acute inflammation phase at 1 day after the immunization (Fig. 8C). Thereafter, the luminescence gradually decreased and was localized at the brain and the spinal cord throughout the observation period by day 28. An IVIS image from day 14 is shown in panel k of Fig. 8B. In contrast, CFA-treated control WIM-6 mice rarely showed luciferase luminescence (panel j). Treatment with pertussis toxin alone did not induce luciferase luminescence in the CNS either (data not shown). Sagittal and transverse section analysis performed with IVIS spectrum computed tomography (IVIS-CT) nicely demonstrated that luciferase luminescence was localized in the brain and spinal cord (arrowheads in the lower panel of Fig. 8D). From 20 days after the immunization, the luminescence intensity gradually decreased, in accordance with the spontaneous remission of the neurological symptoms in the wild-type mice (Fig. 8C). These results thus indicate that the luciferase luminescence detected by the WIM-6 system faithfully represents the disease status of the EAE model.

Nrf2-deficient mice are susceptible to experimental encephalomyelitis.

We next examined the contribution of Nrf2 to the prevention of EAE progression by utilizing Nrf2-deficient mice crossed with the WIM-6 mice. Nrf2-deficient mice exhibited more-severe EAE than wild-type control mice did throughout the natural course of EAE progression (red line in Fig. 8A). The enhanced severity of EAE symptoms in the Nrf2-deficient mice was associated with advanced demyelination in the brain cortex compared with the results seen with the wild-type mice (see luxol fast blue [LFB] staining in Fig. 8B, panel f). The Nrf2-deficient EAE mice showed robust infiltration of F4/80-positive macrophages and microglial cells in the brain (panel i) compared with the wild-type EAE mice (panel h). Furthermore, the brain and spinal cord of the Nrf2-deficient EAE mice showed a higher abundance of endogenous IL6 transcripts than those of the wild-type EAE mice (Fig. 8E).

Consistent with the enhanced neurological severity scores and accompanying severe inflammation, the Nrf2-deficient EAE mice exhibited a higher level of luciferase luminescence in the CNS regions than the wild-type EAE mice showed throughout the observation period (Fig. 8B, panel l, and C).

We found that the level of luciferase luminescence intensity correlated well with the severity of neurological symptoms (Fig. 8C). The IVIS-CT analysis also showed a higher level of luciferase luminescence in the brain and spinal cord of the Nrf2-deficient EAE mice than in those of the wild-type mice (Fig. 8D, upper panel), demonstrating that the WIM-6 system clearly monitored the inflammatory status of CNS in the EAE model. It should be noted that the early increase of luciferase luminescence reflects the acute inflammatory conditions whereas the delayed peak of the EAE score reflects the irreversible damage of neural tissues provoked by the inflammation. Thus, the WIM-6 system adds new means for the assessment of autoimmune degenerative brain disorders.

DISCUSSION

The mechanisms underlying low-grade systemic inflammations associated with oxidative stresses in numerous pathophysiological contexts remain to be elucidated. To address this issue, detection of microinflammations in vivo in various tissues is crucial. In this study, we developed an in vivo inflammation-monitoring system with the use of hIL6-BAC-directed luc reporter transgenic mice in combination with the luciferase bioluminescence imaging technique. This whole-body in vivo monitoring using the hIL6-BAC-Luc transgenic system is referred to as the WIM-6 system. The WIM-6 system provides a sensitive, quantitative, and real-time monitoring system for the induction and resolution of inflammation associated with multiple disease models.

In the LPS-induced sepsis model, robust induction of hIL6-BAC-directed luciferase luminescence was detected around 4 to 6 h after the LPS administration, and the luciferase luminescence was extinguished by 48 h after the administration. It has been reported that robust infiltration of inflammatory cells emerges around 4 to 6 h after LPS administration and that mortality resulting from LPS-induced sepsis occurs mainly within 48 h after the administration (30). Therefore, the time course profile of the luciferase luminescence detected in the WIM-6 system is consistent with the natural course of LPS-induced sepsis. This result underscores that the IL6 expression profile monitored by the WIM-6 system faithfully correlates with the disease status of the LPS-induced sepsis. We surmise that the relatively short half-life (2 to 3 h [31]) and the lack of posttranslational modifications of the luciferase reporter protein have enabled the dynamic real-time monitoring of the status of LPS-induced inflammation by the WIM-6 system.

We first employed a skin inflammation model, as we have been developing the AhR-CA mouse for use in a reliable animal model that faithfully recapitulates that etiological basis of pollution-induced atopic dermatitis (7). As a consequence of crossing the AhR-CA mice with the WIM-6 system, skin inflammation can be monitored continuously without any invasive tissue samplings. Of note, the therapeutic efficacy of dexamethasone against the dermatitis is clearly monitored by the WIM-6 system. On the basis of those results, we propose that the WIM-6 system will be a useful model system for development of therapeutics against skin inflammations.

The second model we have employed is MS, which is one of representative chronic neuroinflammatory diseases caused by autoimmune activity against myelin and oligodendrocytes (12). Subsequent demyelination in the central nervous system promotes progressive neuronal disorders. While EAE has been developed as an animal model for this disease entity, there still remain a number of difficulties for evaluation of the disease severity in this model. Among many important issues to be elucidated, we consider that the following three are especially important. First, evaluation of the disease status of EAE largely depends on subjective scoring of neurological symptoms by visual inspection. Second, precise localization of inflammatory foci and time course changes of inflammatory status within the central nervous system are technically difficult and have not been clarified. Third, while it has been suggested that Nrf2-deficient mice are more susceptible to EAE induction than are wild-type control mice (13), quantitative and subjective evaluation of the inflammatory status during pathological course of EAE in the Nrf2-deficient mice has not been executed due to the lack of a precise inflammation-monitoring system.

The WIM-6 system successfully addresses these three issues. Monitoring using the WIM-6 system revealed that MOG immunization evokes acute inflammation in the central nervous system at as early as 1 day after the immunization. While acute-phase inflammation is gradually attenuated, the neurological symptoms show progressive deterioration later on. This biphasic disease process indicates that accumulated inflammatory insults damage neural tissues, which subsequently develop behavioral abnormalities that can be monitored by EAE scoring in the mice. In contrast, the present imaging provided by the WIM-6 system demonstrates that Nrf2-deficient mice exhibit more-severe neurological symptoms, as the neuronal inflammation seen in Nrf2-deficient mice is more robust than that seen in the wild-type mice. This result underscores the enhanced susceptibility of the Nrf2-deficient mice to EAE induction and indicates that more-robust inflammation evokes more-severe neural damage. We expect to clarify the details of the pathogenic mechanism underlying inflammatory demyelinating diseases by using the WIM-6 system.

The abundance of IL-6 is mainly regulated at the transcription level in response to a broad range of inflammatory and infectious stimuli (4). A series of conventional transfection assays have revealed that a number of transcription factors, including IRF, AP-1, C/EBP, SP1, and NF-κB, mediate the multitude of stimuli and activate the IL6 expression through binding to sequences located in the proximal promoter region (32). Meanwhile, a recent report has shown a broad distribution of evolutionarily conserved regions from approximately 165 kb upstream to 35 kb downstream of hIL6 (32). In the present study, we found that the LPS-induced expression pattern of the hIL6-BAC-directed luciferase luminescence faithfully recapitulates the endogenous IL6 expression pattern in multiple tissues in vivo. These results strongly argue that the putative regulatory elements broadly distributed in the extended flanking sequences of hIL6 participate in the inducible transcriptional activation of hIL6 in the multiple organs. We surmise that these multiple regulatory sequences in the hIL6-BAC-Luc reporter gene contribute to the highly sensitive and physiologically faithful expression of the luciferase reporter in the WIM-6 system.

In summary, in this study, we have developed the WIM-6 system, which provides sensitive monitoring with spatially and temporally high resolution. The WIM-6 system enables us to conduct precise evaluation of the inflammatory status of chronic disease models. The WIM-6 system will extend our understanding of the pathogenic mechanism underlying inflammatory diseases. The process of validation of potential therapeutic drugs for treatment of inflammatory diseases will also be dramatically facilitated by virtue of the sensitivity of and the quantitative measurements enabled by the WIM-6 system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Hirotaka Yamamoto, Eriko Naganuma, and Hiromi Suda for the technical assistance. We thank the Biomedical Research Core of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine for its technical support.

This study was supported in part by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (KAKENHI 22118001 and 24249015 to M.Y. and 24590371 to T.M.), the Core Research for Evolutionary Science and Technology (CREST) research program of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (to M.Y.), and the Naito Foundation, Mitsubishi Foundation, and Takeda Science Foundation (to M.Y.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Kobayashi E, Suzuki T, Yamamoto M. 2013. Roles nrf2 plays in myeloid cells and related disorders. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2013:529219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motohashi H, Yamamoto M. 2004. Nrf2-Keap1 defines a physiologically important stress response mechanism. Trends Mol Med 10:549–557. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirano T, Akira S, Taga T, Kishimoto T. 1990. Biological and clinical aspects of interleukin 6. Immunol Today 11:443–449. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akira S, Isshiki H, Nakajima T, Kinoshita S, Nishio Y, Natsuka S, Kishimoto T. 1992. Regulation of expression of the interleukin 6 gene: structure and function of the transcription factor NF-IL6. Ciba Found Symp 167:47–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kishimoto T. 2005. Interleukin-6: from basic science to medicine—40 years in immunology. Annu Rev Immunol 23:1–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DaVeiga SP. 2012. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis: a review. Allergy Asthma Proc 33:227–234. doi: 10.2500/aap.2012.33.3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tauchi M, Hida A, Negishi T, Katsuoka F, Noda S, Mimura J, Hosoya T, Yanaka A, Aburatani H, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M. 2005. Constitutive expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in keratinocytes causes inflammatory skin lesions. Mol Cell Biol 25:9360–9368. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9360-9368.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mimura J, Yamashita K, Nakamura K, Morita M, Takagi TN, Nakao K, Ema M, Sogawa K, Yasuda M, Katsuki M, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. 1997. Loss of teratogenic response to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in mice lacking the Ah (dioxin) receptor. Genes Cells 2:645–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mimura J, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. 2003. Functional role of AhR in the expression of toxic effects by TCDD. Biochim Biophys Acta 1619:263–268. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4165(02)00485-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arruda LK, Sole D, Baena-Cagnani CE, Naspitz CK. 2005. Risk factors for asthma and atopy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 5:153–159. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000162308.89857.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, Williams H; Phase Three Study Group ISAAC. 2006. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 368:733–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baxter AG. 2007. The origin and application of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat Rev Immunol 7:904–912. doi: 10.1038/nri2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson DA, Amirahmadi S, Ward C, Fabry Z, Johnson JA. 2010. The absence of the pro-antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2 exacerbates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Toxicol Sci 114:237–246. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Katoh Y, Oyake T, Hayashi N, Satoh K, Hatayama I, Yamamoto M, Nabeshima Y. 1997. An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 236:313–322. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itoh K, Tong KI, Yamamoto M. 2004. Molecular mechanism activating Nrf2-Keap1 pathway in regulation of adaptive response to electrophiles. Free Radic Biol Med 36:1208–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.02.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Itoh K, Mimura J, Yamamoto M. 2010. Discovery of the negative regulator of Nrf2, Keap1: a historical overview. Antioxid Redox Signal 13:1665–1678. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itoh K, Mochizuki M, Ishii Y, Ishii T, Shibata T, Kawamoto Y, Kelly V, Sekizawa K, Uchida K, Yamamoto M. 2004. Transcription factor Nrf2 regulates inflammation by mediating the effect of 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2. Mol Cell Biol 24:36–45. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.36-45.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishii Y, Itoh K, Morishima Y, Kimura T, Kiwamoto T, Iizuka T, Hegab AE, Hosoya T, Nomura A, Sakamoto T, Yamamoto M, Sekizawa K. 2005. Transcription factor Nrf2 plays a pivotal role in protection against elastase-induced pulmonary inflammation and emphysema. J Immunol 175:6968–6975. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoh K, Itoh K, Enomoto A, Hirayama A, Yamaguchi N, Kobayashi M, Morito N, Koyama A, Yamamoto M, Takahashi S. 2001. Nrf2-deficient female mice develop lupus-like autoimmune nephritis. Kidney Int 60:1343–1353. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki M, Moriguchi T, Ohneda K, Yamamoto M. 2009. Differential contribution of the Gata1 gene hematopoietic enhancer to erythroid differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 29:1163–1175. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01572-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takai J, Moriguchi T, Suzuki M, Yu L, Ohneda K, Yamamoto M. 2013. The Gata1 5′ region harbors distinct cis-regulatory modules that direct gene activation in erythroid cells and gene inactivation in HSCs. Blood 122:3450–3460. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-476911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki M, Ohneda K, Hosoya-Ohmura S, Tsukamoto S, Ohneda O, Philipsen S, Yamamoto M. 2006. Real-time monitoring of stress erythropoiesis in vivo using Gata1 and beta-globin LCR luciferase transgenic mice. Blood 108:726–733. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller SD, Karpus WJ, Davidson TS. 2010. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in the mouse. Curr Protoc Immunol 88:15.1.1–15.1.20. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1501s88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, Goncalves R, Mosser DM. 2008. The isolation and characterization of murine macrophages. Curr Protoc Immunol 83:14.1.1–14.1.14. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1401s83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu L, Moriguchi T, Souma T, Takai J, Satoh H, Morito N, Engel JD, Yamamoto M. 2014. GATA2 regulates body water homeostasis through maintaining aquaporin 2 expression in renal collecting ducts. Mol Cell Biol 34:1929–1941. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01659-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erta M, Quintana A, Hidalgo J. 2012. Interleukin-6, a major cytokine in the central nervous system. Int J Biol Sci 8:1254–1266. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gauldie J, Richards C, Baumann H. 1992. IL6 and the acute phase reaction. Res Immunol 143:755–759. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(92)80018-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michalopoulos GK. 2007. Liver regeneration. J Cell Physiol 213:286–300. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leung DY, Boguniewicz M, Howell MD, Nomura I, Hamid QA. 2004. New insights into atopic dermatitis. J Clin Invest 113:651–657. doi: 10.1172/JCI21060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thimmulappa RK, Lee H, Rangasamy T, Reddy SP, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW, Biswal S. 2006. Nrf2 is a critical regulator of the innate immune response and survival during experimental sepsis. J Clin Invest 116:984–995. doi: 10.1172/JCI25790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ignowski JM, Schaffer DV. 2004. Kinetic analysis and modeling of firefly luciferase as a quantitative reporter gene in live mammalian cells. Biotechnol Bioeng 86:827–834. doi: 10.1002/bit.20059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samuel JM, Kelberman D, Smith AJ, Humphries SE, Woo P. 2008. Identification of a novel regulatory region in the interleukin-6 gene promoter. Cytokine 42:256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]