Abstract

Objective

To evaluate whether a 12-week supervised exercise program promotes an active lifestyle throughout pregnancy in pregnant women with obesity.

Methods

In this preliminary randomised trial, pregnant women (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) were allocated to either standard care or supervised training, from 15 to 27 weeks of gestation. Physical activity was measured by accelerometry at 14, 28 and 36 weeks, while fitness (oxygen consumption (VO2) at the anaerobic threshold), nutrition (caloric intake and macronutrients percentage) and anthropometry were assessed at 14 and 28 weeks of gestation. Analyses were performed using repeated measures ANOVA.

Results

A total of fifty (50) women were randomised, 25 in each group. There was no time-group interaction for time spent at moderate and vigorous activity (pinteraction = 0.064), but the exercise group’s levels were higher than controls’ at all times (pgroup effect = 0.014). A significant time-group interaction was found for daily physical activity (p = 0.023); similar at baseline ((22.0 ± 6.7 vs 21.8 ± 7.3) x 104 counts/day) the exercise group had higher levels than the control group following the intervention ((22.8 ± 8.3 vs 19.2 ± 4.5) x 104 counts/day, p = 0.020) and at 36 weeks of gestation ((19.2 ± 1.5 vs 14.9 ± 1.5) x 104 counts/day, p = 0.034). Exercisers also gained less weight than controls during the intervention period despite similar nutritional intakes (difference in weight change = -0.1 kg/week, 95% CI -0.2; -0.02, p = 0.016) and improved cardiorespiratory fitness (difference in fitness change = 8.1%, 95% CI 0.7; 9.5, p = 0.041).

Conclusions

Compared with standard care, a supervised exercise program allows pregnant women with obesity to maintain fitness, limit weight gain and attenuate the decrease in physical activity levels observed in late pregnancy.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01610323

Introduction

Physical activity during pregnancy can increase cardiorespiratory fitness [1], decrease gestational weight gain [2] and lower the risk of preeclampsia [3]. However, such benefits remain uncertain in women with obesity. These women are spontaneously less active than their lean counterparts [4], which may exacerbate their already low fitness levels [5] and risk of excessive gestational weight gain [6]. Consequently, exercise programs targeting this population are needed, as they can potentially decrease the risk of perinatal complications.

Increasing exercise levels in pregnant women with obesity appears challenging, as adherence to exercise programs has been of concern in previous trials [7, 8]. Moreover, the efficacy of such interventions to improve physical activity levels throughout pregnancy is usually not objectively measured. Although recommendations have been proposed for pregnant women with obesity [9, 10], their impact on maternal fitness have been poorly studied and accordingly, the type, volume and intensity of physical activity required to maintain fitness in this population is unknown.

As face-to-face, individualized physical activity interventions have the potential to improve adherence to an active lifestyle [11], we sought to investigate its effect in pregnant women with obesity. The primary objective of this study was to evaluate whether an individually supervised, 12-wk moderate-intensity exercise program during the 2nd trimester of pregnancy results in higher physical activity levels throughout pregnancy in women with obesity.

Materials and Methods

Study design

Recruitment for this randomized controlled parallel-group study with a 1:1 allocation ratio was performed at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire (CHU) de Québec and the Centre de santé et de services sociaux de la Vieille-Capitale, from October 2011 to November 2013, with follow-ups completed in June 2014. The intervention and fitness tests took place at the Pavillon de prévention des maladies cardiaques (PPMC, Institut Universitaire de Cardiologie et Pneumologie de Québec). Research Ethics Board of these institutions approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent. The protocol of the study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, following the enrollment of the first participants (NCT01610323, URL https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT01610323?term=NCT01610323&rank=1). As implementing an exercise intervention can be challenging, initial recruitments for this preliminary study aimed at confirming the intervention feasibility. Registration was delayed until funding allowed us to continue the recruitment for this preliminary study. At the time of registration, only 5 participants had completed the primary outcome assessment, which was originally cardiorespiratory fitness following the intervention as mentioned in the original protocol. However, cardiorespiratory testing in pregnant women with obesity raised feasibility issues, especially at 28 weeks, and accordingly the primary outcome was modified for the impact of the intervention on physical activity levels, in accordance with the registered protocol and the sample size requirement for the physical activity outcome (as describe in the “Sample size” section). There are no ongoing trials for this intervention.

Participants

Participants were recruited before the end of the 14th week of gestation at family practice, obstetrical and ultrasound clinics and in the community. Women with a pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30.0 kg/m2, regardless of previous physical activity levels, were eligible if they were 18 years or older, presented a singleton pregnancy and planned to deliver in participating hospitals. Women with diabetes or chronic hypertension before pregnancy were excluded. The absence of physical activity contraindications was verified with the women’s physician and the Physical Activity Readiness Medical Examination for Pregnancy (PARmed-X [12]).

Randomisation

Following baseline assessment, participants were randomly allocated to either the exercise intervention or usual activity. Randomization was stratified according to parity and based on a computer-generated random numbers table. Sealed envelopes were kept in a secure place by a research assistant not involved in the study and provided to a kinesiologist at the time of allocation. Due to the nature of the intervention, kinesiologists in charge of training and participants were not blinded to group assignment. However, all assessors and research assistants in charge of data entry and analyses were blinded to participants’ allocation (defined as “group 1” and “group 2”).

Study protocol

At 14 weeks of gestation (Visit 1), participants were assessed for physical activity, anthropometry, fitness and fetal growth. Physical activity prior to pregnancy, socio-demographic characteristics and obstetrical history were collected by a trained research assistant. Food intakes were also documented, but no recommendations were made regarding them.

The same measurements were performed at 28 weeks (Visit 2), following the intervention period. Finally, women were met at 36 weeks (Visit 3) to document physical activity during the third trimester. Within 72h following delivery, newborn’s anthropometry was evaluated by a trained research assistant. Medical charts were reviewed to collect perinatal outcomes and birth weight.

Study groups

The exercise group was offered a supervised exercise program starting at the 15th week of gestation with free membership in a hospital-based conditioning centre, where kinesiologists were always available for counselling. Participants were individually supervised once a week and invited to complete two more sessions/wk. Consistent with the American College of Sports Medicine Guidelines [10], exercise prescription consisted of 3 weekly 1h sessions, for a total of 36 prescribed sessions over 12 wks.

Each session included a 5–10 min warm-up on a stationary ergocycle, a 15–30 min treadmill walk, a 20 min muscular work-out and a cool-down period. Duration of the cardiovascular training increased progressively from 15 min during the first week to 30 min by the end of the first month. The muscular work-out included dynamic exercises for both lower and upper limbs using the participant’s own body weight, small weights, exercising balls and strength equipment with selective charges. Participants started with 1 set of 10–15 repetitions per exercise and progressed to 2 sets of 15 repetitions, with intensity adjusted to their tolerance level. To enhance motivation, the muscular work-out was modified every 4 weeks (twice during the intervention period). Exercise intensity was self-monitored with heart rate monitors (Polar FT4, Polar Electro, Finland) and the modified Borg Scale [13], with targets at 70% of peak heart rate (measured during the fitness test), and/or at a perceived exertion score of 3-5/10. Participants recorded duration and mean heart rate of each session from their monitors on their exercise log. On non-training days, women were advised to be as active as possible.

The control group was told to continue usual activities without being restrained from doing physical activity. Both groups were given a pamphlet (from Kino-Québec, an agency promoting physical activity) about the benefits of physical activity and appropriate exercises for pregnant women [14].

Outcomes assessment

Physical activity was measured by accelerometry at 14, 28 and 36 weeks of gestation. Women were instructed to wear the accelerometer (GT3X+, ActiGraph, USA) on the hip for 7 consecutive days, with permission to remove it before bedtime. The primary outcome was defined as the time spent at moderate and vigorous physical activity (MVPA) at 36 weeks of gestation. As the number of days with wear time varied across subjects, reporting activity data per day (instead of per week) was more appropriate. Accordingly, we also reported the number of accelerometry counts/day (reflecting total activity), daily time spent at MVPA in periods ≥10 min (minimum duration required to improve fitness [15]) and daily step counts. MVPA was calculated using the Matthews’ cut point [16], previously used in pregnant women with obesity [17]. Accelerometers were operated according to the manufacturer’s specifications, and analyses were performed using Actilife software. Non-wear time (60 min or more of consecutive zeros [18]) was assessed from accelerometry data, with spurious data removed [19]. Per protocol, if accelerometers were worn for less than 8h daily and for less than 5 days, data were excluded [17] from the main analyses. In addition to this analysis, sensitivity analyses without a minimum wear time requirement were conducted, with and without removal of spurious data [19].

Physical activity in the previous month was also measured at each visit using the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire (PPAQ) [17, 20] which specifies the type of physical activity performed, adding to data collected through accelerometry [21]. Time spent at each activity was multiplied by its intensity (in Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET)) [22] and summed to obtain a weekly energy expenditure in METs∙h∙wk-1.

Adherence to exercise prescription was calculated as the number of completed sessions during the intervention, as collected in the participants’ log and verified with heart rate monitors’ recordings.

Maternal weight was measured using an electronic scale (InBody 520, Biospace, USA) at each visit. Height was measured at Visit 1, and skinfolds (Harpenden skinfold calliper, Baty, UK) were measured at 14 and 28 weeks of gestation by an experienced exercise physiologist, as described elsewhere [5]. Skinfolds were used to estimate fat percentage using the Jackson and Pollock’s equation for women [23]. Weight gain outcomes were weight gain from 14 to 36 weeks of gestation, and weight gain from 14 to 28 weeks (at the end of the intervention period). To account for the different time period between two weight evaluations, the rate of weekly weight gain was reported (weight gain divided by the number of weeks between the two weight evaluations). Total gestational weight gain (difference between the last weight before delivery and pre-pregnancy weight as reported in the medical charts) was also calculated.

Cardiorespiratory fitness, defined as oxygen uptake at the anaerobic threshold (VO2 AT), was assessed at 14 and 28 weeks of gestation by a qualified exercise physiologist during a peak treadmill exercise test with gas exchange analysis (Quark B2, version 8.1a, Cosmed, Italy). A standardized procedure was followed [24], using the modified Bruce ramp protocol [25]. VO2 AT was identified by two independent exercise physiologists using the V-slope method [26]. Muscular testing included handgrip strength (Model 78010, Lafayette Instrument Company, USA) and isokinetic strength and endurance of the quadriceps (Biodex System 4, Biodex Medical Systems Inc., USA) following standardized procedures [5, 27–29].

Dietary intakes over the last month were measured at 14 and 28 weeks of gestation using an interviewer-administered food frequency questionnaire [30] with use of food models for estimation of portions.

Fetal growth and uterine arteries mean pulsatility index were evaluated by a certified technician during Doppler studies at 14 and 28 weeks of gestation (Voluson E8 Expert system, GE Healthcare Inc., USA). Neonatal anthropometry included length, head circumference (Models 212 and 416, Seca corp, Germany) and skinfolds (Lange skinfold caliper, Beta Technology, USA). Fat mass and percentage were calculated with a validated equation [31], and birth weight Z-scores adjusted for sex and gestational age were based on Canadian references [32].

Sample size

Sample size was calculated a priori based on previously published accelerometry data reporting that in the third trimester, women with obesity spent 16 ± 16 min/d doing MVPA in bouts ≥10 min [17]. Based on a t-test, a sample size of 21 participants per group allowed detecting an increase of 14 min/d in the intervention group compared to controls, justified by current recommendations (i.e. 30 min/d [33]), with an 80% power and two-sided alpha level at 0.05. With an estimated 15% of losses, 50 participants were recruited.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation and percentage for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical package 9.4 on an intention-to-treat basis. In order to perform a comprehensive analysis of all physical activity measures over time (at 14, 28 and 36 weeks of gestation), repeated measures ANOVA using a linear mixed model were conducted to compare the effect of group allocation (exercise vs control), time (baseline, 28 weeks, 36 weeks) and their interaction on physical activity levels. If a significant “time-group” interaction was found, comparison over time was made for each group separately, and comparison between groups was made at each individual time. Otherwise, main effects were presented. The covariance structure for repeated measures ANOVA was chosen separately for each outcome. The structure with the lowest Akaike Information Crieterion corrected for finite sample (AICc) amongst several of the most popular structures was chosen. The normality assumption of the residuals of the ANOVA was verified by checking the distribution of scaled residuals obtained by the linear mixed model. Skewness and kurtosis coefficients, as well as histograms and Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests, were evaluated and confirmed that the assumption was met. Post hoc tests with the Bonferroni correction were performed to take into account multiple comparisons and keep the familywise error rate at 5%. Sensitivity analyses without a minimum wear time requirement for accelerometry were also conducted, with and without removal of spurious data. As pre-pregnancy physical activity levels could influence the physical activity profile during pregnancy, a sensitivity analysis stratified by pre-pregnancy physical activity level was performed for physical activity outcomes, with women dichotomized as “previously active” or “previously inactive” based on the median value of the pre-pregnancy self-reported energy expenditure spent at sports and exercise. For other outcomes (exploratory analyses for weight gain and neonatal outcomes), groups were compared by Student t test, Wilcoxon rank sum test, χ2 or Fisher’s exact test.

Results

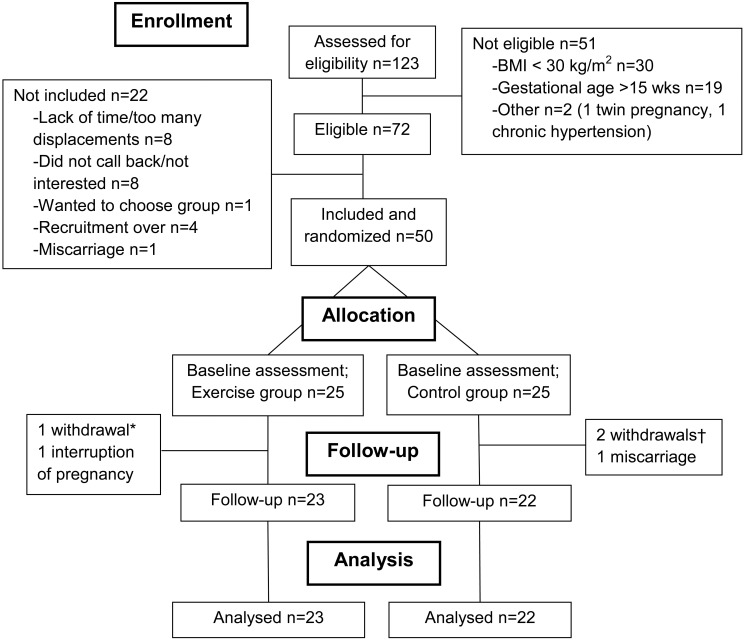

Among 123 interested women, 72 were eligible and 50 were randomized in one of the two study arms (25 per group, see Fig 1). Both groups were similar with respect to baseline socio-demographic characteristics (Table 1). Self-reported physical activity prior to pregnancy was also similar between groups, although the control group reported higher total energy expenditure than the exercise group (Table 1).

Fig 1. Flowchart.

*One participant withdrew after randomization (lack of time); †Two participants withdrew after randomization (unsatisfied with group allocation).

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics at 14 weeks (Visit 1).

| Mean ± SD or n (%) | Exercise group n = 25 | Control group n = 25 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year a | 30.5 ± 3.7 | 31.0 ± 4.0 | 0.664 |

| White b | 24 (96) | 21 (88) | 0.349 |

| Schooling ≥ bachelor degree | 15 (60) | 16 (64) | 0.771 |

| Married or living with a partner | 25 (100) | 25 (100) | 1.000 |

| Employed during 1st trimester | 16 (64) | 17 (68) | 0.765 |

| Number of work hours/wk | 35.9 ± 8.8 | 31.0 ± 11.1 | 0.287 |

| Preventive withdrawal/mandatory leave | 9 (36) | 8 (32) | 0.765 |

| Smoking before pregnancy | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 1.000 |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 1 (4) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Parity ≥ 1 | 14 (56) | 14 (56) | 1.000 |

| Gestational age at visit 1, wk a | 13 4/7 ± 1 1/7 | 14 1/7 ± 1 0/7 | 0.053 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, kg/m 2 | 34.6 ± 5.4 | 33.9 ± 4.5 | 0.684 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI by category b | - | - | 0.232 |

| Obesity class I (30–34.9 kg/m 2 ) | 17 (68) | 16 (64) | - |

| Obesity class II (35–39.9 kg/m 2 ) | 3 (12) | 7 (28) | - |

| Obesity class III (≥ 40 kg/m 2 ) | 5 (20) | 2 (8) | - |

| Pre-pregnancy weight, kg | 93.4 ± 17.6 | 90.7 ± 13.9 | 0.907 |

| Gestational weight gain at visit 1, kg a | 1.6 ± 2.1 | 1.1 ± 3.3 | 0.539 |

| BMI at visit 1, kg/m 2 | 35.2 ± 5.4 | 34.3 ± 4.1 | 0.877 |

| Total self-reported pre-pregnancy energy expenditure (PPAQ), METs·h/wk | 243.4 ± 98.1 | 305.3 ± 174.5 | 0.036 |

| Energy expenditure by intensity, METs·h/wk | - | - | - |

| Sedentary | 80.4 ± 26.7 | 81.1 ± 32.6 | 0.946 |

| Light | 83.7 ± 46.3 | 110.1 ± 58.1 | 0.099 |

| Moderate | 72.8 ± 71.2 | 104.7 ± 117.8 | 0.076 |

| Vigorous | 6.5 ± 7.5 | 9.4 ± 14.3 | 0.968 |

| Energy expenditure by type, METs·h/wk | - | - | - |

| Household and care giving | 76.1 ± 54.6 | 113.6 ± 75.7 | 0.060 |

| Occupational activity | 96.3 ± 40.5 | 104.8 ± 104.3 | 0.857 |

| Sports and exercise | 17.8 ± 12.2 | 18.6 ± 17.6 | 0.698 |

| Transportation | 27.0 ± 24.6 | 27.7 ± 16.5 | 0.341 |

aStudent t-test (other continuous variables evaluated using Wilcoxon rank sum test)

bFisher exact test (other categorical variables evaluated using χ2).

Physical activity assessments

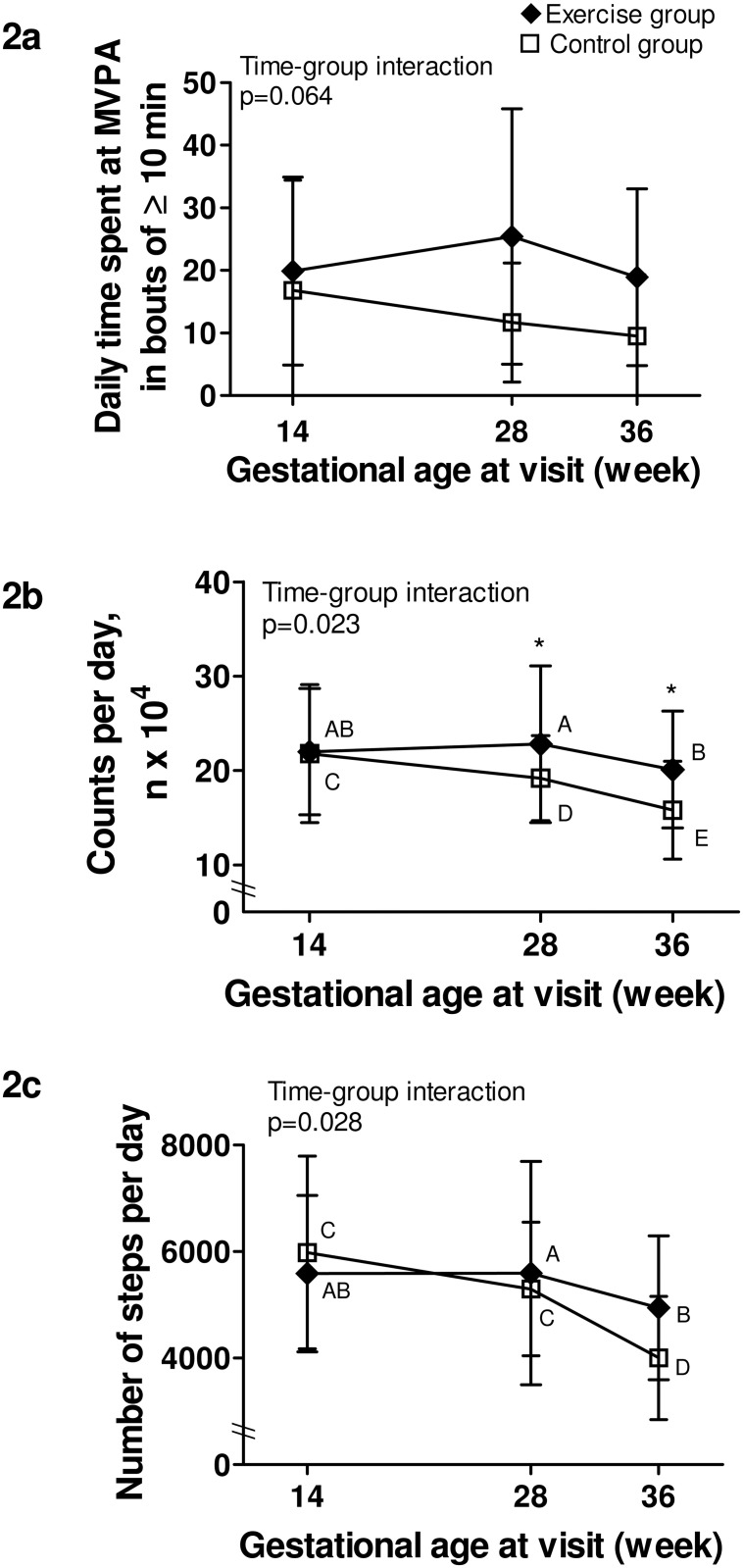

Physical activity data can be found in Table 2. For daily MVPA in bouts ≥10 min (Fig 2a), there was no significant time-group interaction, although a trend was present. There was a significant group effect (p = 0.014), meaning that the exercise group spent more time doing MVPA in bouts ≥10 min than the control group at all times.

Table 2. Physical activity levels throughout the study.

| Baseline at 14 weeks | End of program at 28 weeks | Follow-up at 36 weeks | ANOVA result | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD or n (%) | Exercise group | Control group | Exercise group | Control group | Exercise group | Control group | P-value for interaction |

| Accelerometry, n | 23 | 22 | 20 | 17 | 18 | 16 | - |

| MVPA in bouts, min/d | 19.9 ± 15.0 | 16.8 ± 17.6 | 25.4 ± 20.4 | 11.7 ± 9.5 | 18.9 ± 14.1 | 9.5 ± 9.8 | 0.064 a |

| Counts per day (n x 104) | 22.0 ± 6.7 | 21.8 ± 7.3 | 22.8 ± 8.3 | 19.2 ± 4.5 | 20.1 ± 6.2 | 15.8 ± 5.2 | 0.023 |

| Steps per day | 5587 ± 1472 | 5984 ± 1806 | 5598 ± 2094 | 5298 ± 1252 | 4947 ± 1349 | 4006 ± 1157 | 0.028 |

| Self-reported PA, n | 25 | 25 | 23 | 22 | 23 | 22 | - |

| Total energy expenditure, METs·h/wk | 194.6 ± 71.2 | 226.0 ± 60.0 | 218.1 ± 67.8 | 207.8 ± 72.6 | 185.0 ± 50.8 | 186.8 ± 83.6 | 0.070 b |

| Energy expenditure by intensity, METs·h/wk | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sedentary | 74.4 ± 27.3 | 79.9 ± 27.3 | 69.1 ± 28.9 | 66.4 ± 30.9 | 62.9 ± 25.3 | 63.5 ± 25.5 | 0.65 c |

| Light | 71.8 ± 46.7 | 86.7 ± 32.5 | 89.7 ± 41.2 | 86.3 ± 35.2 | 73.6 ± 27.7 | 78.7 ± 43.6 | 0.23 |

| Moderate | 46.3 ± 33.7 | 56.8 ± 37.0 | 48.5 ± 30.8 | 54.4 ± 45.1 | 41.6 ± 25.3 | 43.8 ± 37.9 | 0.64 |

| Vigorous | 2.2 ± 3.4 | 2.6 ± 8.0 | 10.7 ± 7.1 | 0.8 ± 2.0 | 6.9 ± 5.9 | 0.8 ± 1.9 | <0.0001 |

| Energy expenditure by type, METs·h/wk | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Household and care giving | 71.7 ± 61.5 | 91.7 ± 55.4 | 82.5 ± 52.8 | 86.7 ± 60.4 | 75.3 ± 43.4 | 86.2 ± 76.8 | 0.39 |

| Occupational activity | 55.6 ± 41.4 | 62.3 ± 43.2 | 62.1 ± 47.3 | 48.8 ± 55.4 | 39.7 ± 39.9 | 27.7 ± 39.1 | 0.21 d |

| Sports and exercise | 10.2 ± 8.625 | 8.6 ± 9.9 | 22.4 ± 13.2 | 8.4 ± 6.2 | 15.5 ± 11.2 | 9.3 ± 7.6 | 0.002 |

| Transportation | 21.6 ± 16.9 | 22.2 ± 12.9 | 23.3 ± 15.8 | 25.1 ± 18.4 | 20.4 ± 12.6 | 21.0 ± 16.1 | 0.97 |

MVPA = moderate and vigorous physical activity; PA = physical activity

asignificant group effect, p = 0.014; values significantly higher in the exercise vs control group at all time

bsignificant time effect, p = 0.028; values significantly lower at time 3 compared with time 2 in both groups (adjusted p = 0.027)

csignificant time effect, p = 0.012; values significantly lower at time 3 compared with time 1 in both groups (adjusted p = 0.012)

dsignificant time effect, p = 0.007; values significantly lower at time 3 vs time 1 and time 2 in both groups (adjusted p = 0.001 and p = 0.010).

Fig 2. Objectively measured physical activity levels throughout pregnancy.

Black lozenge: exercise group. White square: control group. Fig 2a. Daily time spent at moderate and vigorous physical activity in bouts of at least 10 min; Fig 2b. Total activity per day, expressed as the daily number of accelerometry counts; Fig 2c. Number of steps per day. P-value is for time-group interaction significance; * Indicates a significant difference (p<0.05) between groups at a specific time point; Different capital letters (A, B, C, D, E) within a group indicate significant differences between time points.

For total activity reported by the number of counts/day (Fig 2b), there was a significant time-group interaction. Similar at baseline, the exercise group was significantly more active than the control group at both 28 and 36 weeks of gestation (p = 0.020 and p = 0.034, respectively). A significant decline in the number of counts/day between each time point was also found in the control group, whereas the exercise group only decreased their activity levels between 28 and 36 weeks.

A significant time-group interaction was also present for daily step counts (Fig 2c). Although not significantly different between groups at any time, there was a trend towards a higher step counts at 36 weeks in the exercise group compared to controls (p = 0.072). Also, while there was a significant difference in the number of steps per day only between 28 and 36 weeks in the exercise group, the control group showed a step counts at 36 weeks that was significantly lower than those at baseline and at 28 weeks.

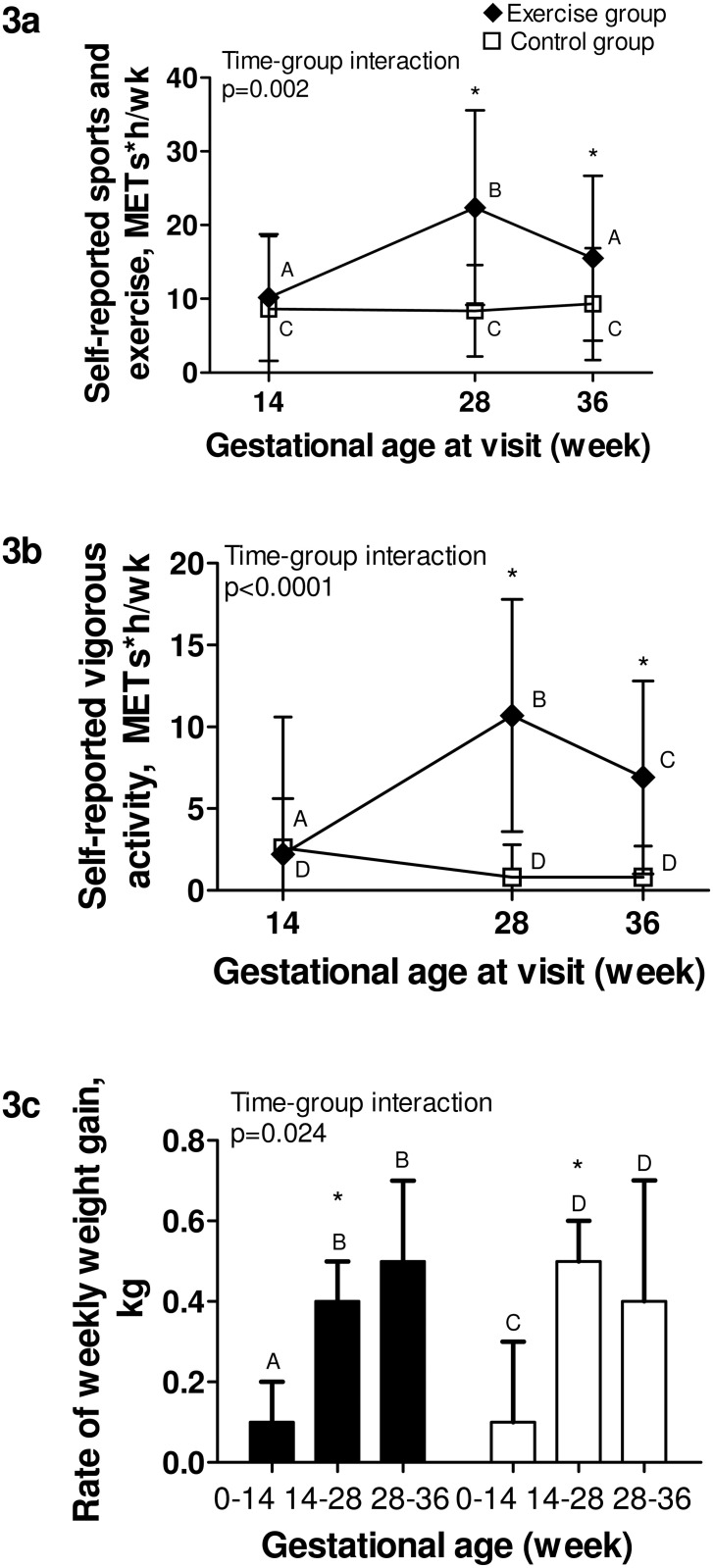

Data from the PPAQ corroborated accelerometry findings (Fig 3a and 3b), as the exercise group reported significantly more time than controls doing sports and exercise activities and vigorous activities at 28 and 36 weeks, respectively. For other domains and intensities of activity from the PPAQ, groups were comparable (Table 2).

Fig 3. Self-reported physical activity and rate of weekly weight gain throughout pregnancy.

Black section: exercise group. White section: control group. Fig 3a. Energy expenditure spent at sports and exercise in the previous month, from the PPAQ; Fig 3b. Energy expenditure spent at vigorous intensity activity in the past month, from the PPAQ; Fig 3c. Rate of weekly gestational weight gain, in kg. P-value is for time-group interaction significance; * Indicates a significant difference (p<0.05) between groups at a specific time point; Different capital letters (A, B, C, D, E) within a group indicate significant differences between time points.

Average accelerometer’s daily wear time was 16.1 ± 3.4 h, 15.5 ± 2.8 h and 14.2 ± 1.9 h at 14, 28 and 36 weeks, respectively. Due to drop-outs (n = 5) or insufficient wear time based on our pre-specified requirement (n = 5, 7 and 11 at 14, 28 and 36 weeks, respectively), accelerometry was not available for all participants. However, non-completers’ characteristics were similar in both groups.

Sensitivity analyses without wear time requirement, with and without removal of spurious data, confirmed and even strengthened the results (S1 Table). Moreover, analyses stratified for pre-pregnancy physical activity levels (“previously active” or “previously inactive”) did not suggest significant interactions between pre-pregnancy physical activity levels and physical activity patterns over time in any group (data not shown).

Adherence to the intervention

The exercise group performed a total of 18.5 ± 10.1 sessions (1.5 sessions/wk), with 15 (60%) and 5 participants (20%) reaching at least 50% and 75% of the 36 prescribed sessions, respectively. Mean duration was 58.8 ± 4.3 min and exercise heart rate was 121 ± 11 beats·min-1 (70.0 ± 5.5% maximal heart rate). There were no adverse events related to the intervention.

Weight gain

Pre-pregnancy weight and weight gain prior to inclusion in the study did not differ between groups (Table 1). However, the rate of weekly weight gain showed a different profile over time between groups (p-value for interaction = 0.024, Fig 3c). Prior to inclusion in the study, the rate of weekly weight gain did not differ between groups (0.11 ± 0.15 kg/wk vs 0.08 ± 0.23 kg/wk for the exercise and control groups, respectively), while during the program, the exercise group gained less weight per week than the control group (0.35 ± 0.14 kg/wk vs 0.46 ± 0.15 kg/wk for the exercise and control groups, respectively, p = 0.018), despite similar nutritional intakes (Table 3). The control group experienced an increase in fat percentage during this period, as compared to the exercise group (Table 3). However, the rate of weekly weight gain did not differ between groups following the end of the intervention until Visit 3 (0.47 ± 0.24 kg/wk vs 0.45 ± 0.29 kg/wk for the exercise and control groups, respectively), nor did total gestational weight gain for the entire pregnancy (S2 Table).

Table 3. Maternal fitness, anthropometry and nutritional intakes at 14 and 28 weeks of gestation.

| Visit 1 (14 weeks) | Visit 2 (28 weeks) | Change from 14 to 28 weeks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Exercise group n = 25 | Control group n = 25 | Exercise group n = 23 | Control group n = 22 | Difference between groups (95% CI) |

| VO2 AT, ml∙kg -1 ∙min -1 | 15.1 ± 2.3 a | 16.0 ± 1.9 | 15.1 ± 1.6 b | 14.9 ± 2.2 | 1.1 (-0.03; 1.5) |

| Change in VO2 AT relative to baseline value, % | - | - | 1.6 ± 13.3 b | -6.5 ± 9.9 | 8.1 (0.7; 9.5) c |

| Dominant handgrip strength, kg | 31.8 ± 4.5 | 32.3 ± 5.9 | 31.4 ± 4.7 | 31.5 ± 5.9 | -0.4 (-1.8; 1.0) |

| Quadriceps strength, N·m d | 134.6 ± 26.8 | 140.7 ± 21.6 | 128.8 ± 33.8 | 132.2 ± 26.2 | 3.9 (-13.4; 21.3) |

| Quadriceps endurance, N·m d | 706.2 ± 216.4 | 698.1 ± 125.0 | 730.0 ± 159.9 | 717.4 ± 138.2 | -10.8 (-111.4; 89.9) |

| Estimated fat percentage | 40.8 ± 6.5 | 39.8 ± 6.1 | 40.6 ± 6.6 | 42.4 ± 4.8 | -2.4 (-4.1; -0.8) e |

| Daily caloric intake, kcal | 2177 ± 724 | 2198 ± 536 | 2319 ± 558† | 2157 ± 622 | 122 (-261; 505) |

| % calories from fat | 32.7 ± 4.7 | 34.9 ± 5.1 | 31.6 ± 5.3† | 33.1 ± 4.2 | 0.9 (-2.5; 4.4) |

| % calories from carbohydrates | 50.8 ±6.1 | 49.3 ±5.7 | 52.1 ± 6.8† | 51.3 ± 5.4 | -1.0 (-5.2; 3.2) |

| % calories from proteins | 18.8 ± 2.3 | 17.9 ±2.6 | 18.6 ± 3.1† | 17.7 ± 2.9 | -0.1 (-1.7; 1.6) |

VO2 AT = oxygen consumption at the anaerobic threshold

an = 24

bn = 22

cp<0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum test

dn = 22 and 24 at baseline, and n = 19 and 20 at 28 weeks in exercise and control groups, respectively

ep<0.05, Student t test.

Changes in fitness

At baseline, cardiorespiratory fitness was similar between groups. Following the intervention, VO2 AT increased slightly in the exercise group, whereas it decreased in the control group (Table 3). There was no difference between groups for muscular strength and endurance following the intervention (Table 3).

Perinatal and neonatal outcomes

At 28 weeks, no differences were found between groups for either mean uterine arteries pulsatility index (data not shown) or estimated fetal weight (1205 ± 169 vs 1219 ± 230 g for exercise and control groups, respectively). There were no differences between groups for birth weight, gestational age at delivery, rate of hypertensive disorders, gestational diabetes or caesarean delivery (S2 Table).

Discussion

A supervised exercise intervention from 15 to 27 weeks of pregnancy was effective in attenuating the decline in physical activity observed in women with obesity. Indeed, the intervention allowed women to maintain or increase their physical activity levels through the 28th week of pregnancy, whereas it decreased in the control group. This improvement was also supported by a maintained cardiorespiratory fitness level and limited weight gain during the intervention period in the exercise group, compared to controls.

The exercise group also remained more active than the control group during the third trimester, as demonstrated by higher accelerometry counts and self-reported energy expenditure. Despite these higher levels in the exercise group, both groups decreased their activity levels between 28 and 36 weeks of gestation, with values near baseline levels and significantly lower than baseline levels for the exercise and control groups at 36 weeks, respectively. This probably reflects the end of the intervention and the fact that some activities become less comfortable as pregnancy progresses. Therefore, to maintain higher levels of physical activity throughout pregnancy, a follow-up until delivery appears necessary. The advantage of our 12-wk intervention in mid-pregnancy was that it allowed establishing that a supervised exercise program could increase fitness and physical activity levels, with the assessment of a retention effect following the end of the intervention. Seizing the opportunity of pregnancy to promote healthy life habits is important, but taking into account the reality of pregnant women with obesity is also crucial. In that sense, creativity and alternatives to individual, center-based intervention might be needed in late pregnancy to sustain the newly acquired physical activity habit (e.g. follow-up to reinforce behavior, walking club or group activities, or home-based practice).

Increasing physical activity levels with a goal of reaching physical activity recommendations throughout pregnancy is important, as it might help pregnant women in achieving adequate gestational weight gain [34, 35] through an increased energy expenditure, lower their risk of gestational diabetes [35] and fetal macrosomia [36] through a higher muscular glucose uptake [37] and lower their risk of preeclampsia [3] through an anti-inflammatory effect on markers such as C-reactive protein [38] and cytokines [39]. Although the present study was not designed to test these hypotheses, our results remain important as they highlight the feasibility for pregnant women with obesity to as least maintain their physical activity levels during pregnancy and that such levels, even below current recommendations, can induce benefits on cardiorespiratory fitness and gestational weight gain. Indeed, based on the present findings, a combined 1h cardiovascular and muscular moderate-intensity training performed 3 times every two weeks by pregnant women with obesity appears sufficient to maintain fitness and to have a marginal impact on weekly weight gain. Nevertheless, this does not mean that obese pregnant women should stop following current physical activity guidelines; this should be viewed as a minimal threshold to attain in order to reap some health benefits, while more benefits can be expected with higher levels of physical activity [40].

Few studies have focused solely on exercise interventions in pregnant women with obesity, limiting our understanding of the isolated effects of physical activity on maternal and neonatal outcomes. A previous study in pregnant women (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) did not report significant effects on physical activity levels or weight gain with exercise compared to standard care [7]. However, less than 20% of their participants achieved half the exercise sessions, compared to 60% in the present study. Individual coaching and availability of exercise specialists accustomed to the management of patients with specific needs in the present study might explain these differences. Still, with a goal of 3 exercise sessions/wk, we were expecting women to complete at least 2 sessions/wk. All women were individually supervised once a week, but they had difficulty completing other sessions on their own, suggesting that having an incentive such as a scheduled session with an exercise specialist might be needed to further increase physical activity levels in these women. Other physical activity modalities might facilitate adherence in this population, such as home-based training. Indeed, a recent study showed a 96% adherence to a 6-wk home-based exercise program in diabetic pregnant women [41]. As in the present study, flexible supervision appears as an important component of a successful intervention with pregnant women, either with obesity or high-risk pregnancy.

Although this study focused on physical activity, the absence of nutritional counselling might have reduced the potential for lowering gestational weight gain [42]. The exercise group remained more active than the control group in the 3rd trimester, but the effect on weight gain observed during the intervention did not persist until delivery. It is also important to recognize that even if the intervention had a significant impact on the rate of gestational weight gain during the training period, it was not sufficient to allow women to gain within the Institute of Medicine’s recommended levels for weekly weight gain (0.2–0.3 kg/wk) and for total gestational weight gain (5–9 kg) [43]. However, our single behavior intervention had positive effects on women’s health, without adverse effects on nutritional intakes and no apparent effect on fetal growth. Nevertheless, due to our sample size, conclusions cannot be drawn about the effects of our intervention on weight gain during pregnancy.

Following the 12-wk intervention period, VO2 AT decreased by 6.5% in the control group while it increased by 1.6% in the exercise group. This small change in the exercise group could be due to the lower than expected volume of exercise performed by participants (1.5 vs 3 sessions per week), as a dose-response relationship is usually expected between exercise volume and fitness improvement [40]. Indeed, a previous study performed in overweight pregnant women found an 18% increase in VO2 AT in their exercise group following a 12-wk intervention [44]. The better adherence found in their study (28 ± 15 sessions over 12 weeks) could partly explain these different findings, as well as the differences in study population characteristics and in the method used to determine the anaerobic threshold. Other potential reasons for the small increase in fitness seen in the present study include the variation in baseline fitness levels between subjects, as those presenting lower levels were probably less active initially, which gave them a better potential for improvement compared to those with a higher fitness level [45], and the interindividual heterogeneity in responsiveness to training (i.e. genetic predispositions) [46]. Nevertheless, although the change over time in VO2 AT was relatively small in the exercise group, a training effect was still observed, considering the decreased VO2 AT in the control group.

The present study has some limitations. Despite a low drop-out rate (10%), some participants did not adequately complete accelerometry measurements [17], reducing power to show a difference between groups. However, our results remain robust as non-completers were not different between groups and because our results were corroborated by sensitivity analyses and by concordant findings with subjective measures. The social support/interaction with the study staff may have been partially responsible for some observed differences in outcomes between the study arms. However, our trial was pragmatic and objective measurements such as accelerometry and fitness data are less prone to be affected by the support given to participants or by a desirability bias. Fat percentage estimates were based on widely used equations although not validated during pregnancy, as no consensus exists on which anthropometric method should be used to reliably determine body composition during pregnancy [47]. Because it was not possible to have skinfold measures at 36 weeks made by the same assessor as for the first two visits and to avoid high inter-observer variability [48], this assessment was not performed. Finally, results may not be generalizable to all pregnant women with obesity, as our sample included mostly white women with higher education and living with a partner.

Conclusion

This preliminary study suggests the feasibility of an exercise intervention during pregnancy for women with obesity to enable them to maintain and even increase their physical activity levels, following a supervised exercise program during mid-pregnancy. From a practical perspective, pregnant women with uncomplicated pregnancy should be encouraged to lead an active pregnancy and referred to competent specialists. A minimum of 3 exercise sessions every two weeks appears necessary to maintain fitness in pregnant women with obesity, but a higher volume of exercise might induce greater benefits on other outcomes such as gestational weight gain. Larger trials are needed to determine short and long term benefits of exercise during pregnancy on maternal and child health.

Supporting Information

(DOC)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Paul Poirier, PPMC’s medical director, for his kind cooperation, Guy Fournier, research assistant at IUCPQ, who performed the cardiorespiratory testing, and Anne-Sophie Julien, biostatistician at the CHU de Québec, for statistical support.

Data Availability

Data from the "Inter GO FIT" study are available from the Dryad Digital Repository (URL http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.87f03).

Funding Statement

This study was funded by an operating grant from the Fondation des Étoiles (grant number F-61359, URL: http://www.fondationdesetoiles.ca/fr). Salaries were supported by the following sources: MB is a doctoral scholarship holder from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (URL http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/193.html). IM and EB are recipients of a Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé clinician scientist award (URL http://www.frqs.gouv.qc.ca/en/accueil). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Kramer MS, McDonald SW. Aerobic exercise for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;19(3):CD000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thangaratinam S, Rogozinska E, Jolly K, Glinkowski S, Duda W, Borowiack E, et al. Interventions to reduce or prevent obesity in pregnant women: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(31):iii–iv, 1–191. 10.3310/hta16310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aune D, Saugstad OD, Henriksen T, Tonstad S. Physical activity and the risk of preeclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2014;25(3):331–43. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Renault K, Norgaard K, Secher NJ, Andreasen KR, Baldur-Felskov B, Nilas L. Physical activity during pregnancy in normal-weight and obese women: compliance using pedometer assessment. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;32(5):430–3. 10.3109/01443615.2012.668580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bisson M, Almeras N, Plaisance J, Rheaume C, Bujold E, Tremblay A, et al. Maternal fitness at the onset of the second trimester of pregnancy: correlates and relationship with infant birth weight. Pediatr Obes. 2013;8(6):464–74. 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00129.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holowko N, Mishra G, Koupil I. Social inequality in excessive gestational weight gain. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38(1):91–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oostdam N, van Poppel MNM, Wouters M, Eekhoff EMW, Bekedam DJ, Kuchenbecker WKH, et al. No effect of the FitFor2 exercise programme on blood glucose, insulin sensitivity, and birthweight in pregnant women who were overweight and at risk for gestational diabetes: results of a randomised controlled trial. Bjog-an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2012;119(9):1098–107. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03366.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vinter CA, Jensen DM, Ovesen P, Beck-Nielsen H, Jorgensen JS. The LiP (Lifestyle in Pregnancy) Study A randomized controlled trial of lifestyle intervention in 360 obese pregnant women. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(12):2502–7. 10.2337/dc11-1150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mottola MF. Exercise prescription for overweight and obese women: pregnancy and postpartum. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2009;36(2):301–16, viii 10.1016/j.ogc.2009.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Exercise Prescription for Healthy Populations and Special Considerations: Pregnancy In: Thompson WR, Gordon NF, Pescatello LS, editors. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 8th edition Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2010. p. 183–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Richards J, Hillsdon M, Thorogood M, Foster C. Face-to-face interventions for promoting physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD010392 10.1002/14651858.CD010392.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.PARmed-X. PARmed-X for pregancy, Physical activity readiness medical examination. 2002; Available: http://www.csep.ca/cmfiles/publications/parq/parmed-xpreg.pdf.

- 13. Wilson RC, Jones PW. A comparison of the visual analogue scale and modified Borg scale for the measurement of dyspnoea during exercise. Clin Sci (Lond). 1989;76(3):277–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kino-Québec. Active pour la vie: L'activité physique pendant et après la grossesse. In: Québec Gd, editor.: Ministère de l'Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15. US. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matthew CE. Calibration of accelerometer output for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(11 Suppl):S512–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chandonnet N, Saey D, Almeras N, Marc I. French Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire compared with an accelerometer cut point to classify physical activity among pregnant obese women. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38818 10.1371/journal.pone.0038818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, Buchowski MS, Beech BM, Pate RR, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003–2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(7):875–81. 10.1093/aje/kwm390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Evenson KR, Terry JW Jr. Assessment of differing definitions of accelerometer nonwear time. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2009;80(2):355–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chasan-Taber L, Schmidt MD, Roberts DE, Hosmer D, Markenson G, Freedson PS. Development and validation of a Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(10):1750–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bell R, Tennant PW, McParlin C, Pearce MS, Adamson AJ, Rankin J, et al. Measuring physical activity in pregnancy: a comparison of accelerometry and self-completion questionnaires in overweight and obese women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;170(1):90–5. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9 Suppl):S498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jackson AS, Pollock ML, Ward A. Generalized equations for predicting body density of women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1980;12(3):175–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bisson M, Rheaume C, Bujold E, Tremblay A, Marc I. Modulation of blood pressure response to exercise by physical activity and relationship with resting blood pressure during pregnancy. J Hypertens. 2014;32(7):1450–7. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaminsky LA, Whaley MH. Evaluation of a new standardized ramp protocol: the BSU/Bruce Ramp protocol. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1998;18(6):438–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wasserman K, Stringer WW, Casaburi R, Koike A, Cooper CB. Determination of the anaerobic threshold by gas exchange: biochemical considerations, methodology and physiological effects. Zeitschrift fur Kardiologie. 1994;83 Suppl 3:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bohannon RW. Dynamometer measurements of hand-grip strength predict multiple outcomes. Percept Mot Skills. 2001;93(2):323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harbo T, Brincks J, Andersen H. Maximal isokinetic and isometric muscle strength of major muscle groups related to age, body mass, height, and sex in 178 healthy subjects. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(1):267–75. 10.1007/s00421-011-1975-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Danneskiold-Samsoe B, Bartels EM, Bulow PM, Lund H, Stockmarr A, Holm CC, et al. Isokinetic and isometric muscle strength in a healthy population with special reference to age and gender. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2009;197 Suppl 673:1–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goulet J, Nadeau G, Lapointe A, Lamarche B, Lemieux S. Validity and reproducibility of an interviewer-administered food frequency questionnaire for healthy French-Canadian men and women. Nutr J. 2004;3:13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Catalano PM, Thomas AJ, Avallone DA, Amini SB. Anthropometric estimation of neonatal body-composition. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;173(4):1176–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, Joseph KS, Allen A, Abrahamowicz M, et al. A new and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):E35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. ACOG. ACOG committee opinion. Exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Number 267, January 2002. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;77(1):79–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Choi J, Fukuoka Y, Lee JH. The effects of physical activity and physical activity plus diet interventions on body weight in overweight or obese women who are pregnant or in postpartum: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prev Med. 2013;56(6):351–64. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sanabria-Martinez G, Garcia-Hermoso A, Poyatos-Leon R, Alvarez-Bueno C, Sanchez-Lopez M, Martinez-Vizcaino V. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions on preventing gestational diabetes mellitus and excessive maternal weight gain: a meta-analysis. BJOG. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wiebe HW, Boule NG, Chari R, Davenport MH. The effect of supervised prenatal exercise on fetal growth: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1185–94. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bessinger RC, McMurray RG, Hackney AC. Substrate utilization and hormonal responses to moderate intensity exercise during pregnancy and after delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(4):757–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hawkins M, Braun B, Marcus BH, Stanek E 3rd, Markenson G, Chasan-Taber L. The impact of an exercise intervention on C—reactive protein during pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:139 10.1186/s12884-015-0576-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. van Poppel MN, Peinhaupt M, Eekhoff ME, Heinemann A, Oostdam N, Wouters MG, et al. Physical activity in overweight and obese pregnant women is associated with higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines and with reduced insulin response through interleukin-6. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(4):1132–9. 10.2337/dc13-2140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1334–59. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Halse RE, Wallman KE, Newnham JP, Guelfi KJ. Home-based exercise training improves capillary glucose profile in women with gestational diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(9):1702–9. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thangaratinam S, Rogozinska E, Jolly K, Glinkowski S, Roseboom T, Tomlinson JW, et al. Effects of interventions in pregnancy on maternal weight and obstetric outcomes: meta-analysis of randomised evidence. BMJ. 2012;344:e2088 10.1136/bmj.e2088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, editors. Washington (DC): Institute of Medicine and National Research Council Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight Guidelines; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Santos IA, Stein R, Fuchs SC, Duncan BB, Ribeiro JP, Kroeff LR, et al. Aerobic exercise and submaximal functional capacity in overweight pregnant women: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(2):243–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sisson SB, Katzmarzyk PT, Earnest CP, Bouchard C, Blair SN, Church TS. Volume of exercise and fitness nonresponse in sedentary, postmenopausal women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3):539–45. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181896c4e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bouchard C, Rankinen T. Individual differences in response to regular physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(6 Suppl):S446–51; discussion S52-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Robic T, Benedik E, Fidler Mis N, Bratanic B, Rogelj I, Golja P. Challenges in determining body fat in pregnant women. Ann Nutr Metab. 2013;63(4):341–9. 10.1159/000358339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fuller NJ, Jebb SA, Goldberg GR, Pullicino E, Adams C, Cole TJ, et al. Inter-observer variability in the measurement of body composition. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1991;45(1):43–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

Data from the "Inter GO FIT" study are available from the Dryad Digital Repository (URL http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.87f03).