Abstract

Little is known about adult women with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), however available evidence suggests that they experience social impairment. Online social networking websites such as Facebook have become endemic outlets through which emerging adults communicate with peers. No study has examined the peer interactions of emerging adults with childhood histories of ADHD in this developmentally relevant online domain. Participants in the current study were an ethnically diverse sample of 228 women, 140 of whom met diagnostic criteria for ADHD in childhood and 88 who composed a matched comparison sample. These women were assessed at three time points spanning 10 years (mean age = 9.6 at Wave 1, 14.1 at Wave 2, 19.6 at Wave 3). After statistical control of demographic covariates and comorbidites, childhood ADHD diagnosis predicted, by emerging adulthood, a greater stated preference for online social communication and a greater tendency to have used online methods to interact with strangers. A childhood diagnosis of ADHD also predicted observations of fewer Facebook friends and less closeness and support from Facebook friends in emerging adulthood. These associations were mediated by a composite of face-to-face peer relationship impairment during childhood and adolescence. Intriguingly, women with persistent diagnoses of ADHD from childhood to emerging adulthood differed from women with consistent comparison status in their online social communication; women with intermittent diagnoses of ADHD had scores intermediate between the other two groups. Results are discussed within the context of understanding the social relationships of women with childhood histories of ADHD.

Keywords: ADHD, women, social functioning, Facebook, online social communication

Adult women with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are underrepresented in the existing literature relative to men. Yet ADHD is at least as impairing to females as it is to males, across broad life domains (Gershon, 2002; see also Hinshaw et al., 2012). One reason why females with ADHD are understudied is that girls and women are less likely than boys and men with this condition to display hyperactivity/impulsivity and comorbid disruptive behaviors that catch the attention of family members and teachers (Gaub & Carlson, 1997). In addition, the study of female as well as male adults with ADHD is challenged by difficulties in recruitment of representative samples (e.g., many studies rely on college students) and valid assessment (e.g., the absence of parents and teachers to report on symptoms; trouble documenting that symptoms began in childhood; Barkley, Murphy, & Fischer, 2008). In short, there is a pressing need to investigate long-term outcomes in women with ADHD or histories of childhood ADHD. A longitudinal investigation of girls with ADHD recruited from community sources and followed prospectively may provide an optimal means of assessing functioning among adult women with challenges regarding inattention and impulse control.

Peer Relationship Impairments

Problems in peer relationships are significant impairments for individuals with ADHD. Preadolescent girls and boys with ADHD tend to have few friendships, as well as less positivity (e.g., less companionship/shared recreational activities and less validation/caring) in any friendships they do have (Hoza et al., 2005; Mikami, 2010). Such peer problems persist for many if not most adolescents with ADHD of both genders (Bagwell, Molina, Pelham, & Hoza, 2001). However, substantially less is known about social impairment among emerging adults with ADHD or with histories of this disorder.

Assessing the construct of peer impairment in adulthood presents unique challenges. Relative to childhood or adolescence, when a majority of peer interactions occur in school, emerging adults interact in a diversity of settings without defined boundaries, which impedes traditional ways of measuring peer relationships such as classroom sociometrics or teacher appraisals (Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982). Although it is common for non-clinical adult samples to self-report on quantity of friendships and positivity/negativity in these relationships (Furman & Buhrmester, 2009), self-report measures may be particularly vulnerable to bias among individuals with ADHD (including adults), who tend to overestimate their social competence (Lui, Johnston, Lee, & Lee-Flynn, 2013). As such, developmentally appropriate, observational means of assessing peer relationships in adulthood are often lacking.

Nonetheless, the limited extant research suggests that peer impairments do persist for both males and females with ADHD across the lifespan. College students with ADHD are rated as less socially competent by peers relative to comparison students (Canu & Carlson, 2003). Romantic partnerships are an important component of close peer relationships for emerging adults; initial evidence suggests that college students with ADHD have more conflict in their romantic relationships (Canu, Tabor, Michael, Bazzini, & Elmore, 2014), and that adults with ADHD are more likely to be divorced (Klein et al., 2012), relative to typically developing individuals of similar ages.

Developmental psychology theories provide an explanation for the continuity of peer problems for individuals with ADHD. Children are thought to learn key social skills (e.g., perspective-taking, conflict management) in their friendships (Pedersen, Vitaro, Barker, & Borge, 2007). Early adolescents must display these social skills in order to increase the intimacy, closeness, and support in their friendships, and these experiences set the stage for romantic relationships in later adolescence and adulthood (Pedersen et al., 2007). Children with ADHD who are deprived of positive peer interactions miss socialization experiences that would otherwise predispose them toward healthy interpersonal relationships in later years (Mikami, 2010). The cumulative effects of peer problems may explain why a childhood ADHD diagnosis could predict peer difficulties in adulthood even in the absence of a current ADHD diagnosis.

Online Social Communication

Online peer interactions are ubiquitous among emerging adults, with 90% of individuals ages 18–29 socially communicating through online channels, most commonly Facebook (Pew Internet and American Life Project, 2013). These statistics, combined with the limitations described above of other methods used to assess peer relationships, suggest the importance of assessing social interactions in the online domain for emerging adults (Pempek, Yermolayeva, & Calvert, 2009; Valkenburg & Peter, 2009). Yet there is no existing work that examines how emerging adults with ADHD interact online, with the majority of any relevant work cross-sectional and relying exclusively on self-report measures.

Emerging adults with ADHD (and histories of childhood ADHD) may use online social communication differently than do their typically developing peers. Studies suggest that youth with anxiety and depression symptoms (Nishimura, 2003), as well those who experience impaired face-to-face relationships (Wolak, Mitchell, & Finkelhor, 2003), prefer online over face-to-face communication. Youth with anxiety/depression and poorer face-to-face relationships are also more likely to engage with strangers online as opposed to with people they also know in face-to-face contexts (Birnie & Horvath, 2002; Subrahmanyam, Reich, Waechter, & Espinoza, 2008). The difficulties these individuals face in establishing positive connections in person are theorized to motivate their preference for online social communication methods and their seeking of connections with strangers online (Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, 2003).

We note that the majority of the existing research has correlated, at a single time point, individuals’ self-reported symptoms or social difficulties with their endorsed preference for online communication and/or patterns of engaging with strangers online. However, one study found that self-reported depressive symptoms at age 13 prospectively predicted emerging adults’ preference for online communication at age 20, after statistical control of current depressive symptoms (Szwedo, Mikami, & Allen, 2011). In addition, observations of conflictual parent-teen interactions at age 13 predicted self-reports at age 20 of having formed a close friendship with someone known exclusively online (Szwedo et al., 2011).

Emerging adults with ADHD (or histories of ADHD) may also have a different quality of online interactions, characterized by reductions in the number of friends as well as less positivity in online relationships. Friendship quantity and the positivity versus negativity of the relationship are historically considered to be key features of face-to-face friendships (Hartup, 1995), and we translate these constructs to the online domain. It is thought that precisely because individuals with psychopathology tend to have online interactions with strangers, these online friendships are more likely to be fewer, as well as less close and supportive (Kraut et al., 2002; Kraut et al., 1998). Also, individuals with impaired face-to-face relationships may play out the same negative patterns online (Mitchell, Finkelhor, & Becker-Blease, 2007). In support of these ideas, research suggests that youth with higher self-reported symptoms of depression/anxiety, as well as those with few friends in face-to-face networks, report having fewer friends online as well as more superficial interactions with friends on Facebook and through instant messaging (Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2007; Feinstein, Bhatia, Hershenberg, & Davila, 2012; Sheldon, 2013; Valkenburg & Peter, 2007). Although longitudinal and observational studies of this topic are rare, one study found that youths’ depression and aggressive behavior, as well as conflict in face-to-face friendship interactions at age 13, predicted observations of fewer Facebook friends and less closeness and support in interactions with these Facebook friends at age 20 (Mikami, Szwedo, Allen, Evans, & Hare, 2010).

Given findings that individuals with psychopathology and with poor social competence appear drawn to the internet for social communication, tend to interact with strangers online, and have poorer quality interactions online (e.g., fewer friends and less positivity in the relationship), it is plausible that similar patterns exist for emerging adults with ADHD. Research suggests that adults who self-report having ADHD symptoms endorse more internet addiction (Carli et al., 2012; Yen, Yen, Chen, Tang, & Ko, 2009). Still, despite the importance of the online domain for emerging adults, we are unaware of any existing study that examines online social communication among individuals with clinical diagnoses of ADHD (or histories of ADHD).

Associations between childhood ADHD and problematic online social interactions in emerging adulthood may be mediated by difficulties in face-to-face relationships that individuals with ADHD often experience. Poor face-to-face relationships may motivate individuals to reach out to strangers online (Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, 2003). A history of peer problems may deprive youth of opportunities to learn social skills (Pedersen et al., 2007), which could explain poorer online interactions as emerging adults. As such, individuals with histories of childhood ADHD may have experienced impaired social interactions in face-to-face contexts in childhood and adolescence, such that in emerging adulthood they also show poorer social interactions in the age-relevant online context.

Gender and Online Social Communication

Although little is known about women with ADHD overall, there are reasons why online social relationships are likely to be poor in this population. The ability to engage in witty, fluent, verbal communication with astute self-presentation in a public forum has been theorized to be essential for successfully making connections on social networking websites (Caers et al., 2013; Gosling, 2009; Subrahmanyam et al., 2008). From early ages, the peer relationships of girls tend to involve verbal dialogue over physical play (Maccoby, 2002); therefore, Facebook interactions fit the type of communication that females prioritize over males (Joiner et al., 2005). Indeed, females are slightly more likely to use Facebook as are males, demonstrating the relevance of this medium for women (Pew Internet and American Life Project, 2013), and females are more likely than males to post online content that is reflective and narrative in style (Subrahmanyam, Garcia, Harsono, Li, & Lipana, 2009). However, the symptoms of ADHD are detrimental to the verbal back-and-forth communication prioritized by females (Keenan & Shaw, 1997). Although to our knowledge this is the first study of online social communication among emerging adults with ADHD or childhood histories of ADHD (of either gender), a suggestive study found that college students’ self-reported ADHD symptoms were more highly correlated with self-reported difficulty modulating internet use in women than in men (Yen et al., 2009).

Study Aims and Hypotheses

We examined peer functioning in the developmentally sensitive medium of online social communication among emerging adult women with and without histories of childhood ADHD, who were participants in a 10-year prospective longitudinal study. In all analyses we considered the impact of ADHD after statistical control of disruptive behavior and internalizing comorbidities. Among children with ADHD, comorbid disruptive behavior disorders worsen social functioning (Pfiffner, Calzada, & McBurnett, 2000). Evidence for the effects of comorbid internalizing disorders is mixed (Pfiffner et al., 2000); however, given consistent associations between internalizing problems and online social communication patterns (e.g., Davila et al., 2012), it is possible that such comorbidities may be quite relevant.

Our first aim was to characterize use of online social communication. We predicted that emerging adult women with childhood histories of ADHD, relative to those without childhood ADHD, would self-report greater preference for online methods of social communication and greater interaction with strangers online. Second, we aimed to examine the quality of online interactions. Using observational measures, we predicted that women with childhood histories of ADHD would display poorer quality Facebook interactions (fewer Facebook friends and less closeness and support with these friends) relative to women without childhood histories of ADHD. Next, we investigated whether peer impairment in face-to-face contexts mediated the link between childhood ADHD diagnosis and emerging-adult online social communication. Finally, we explored whether participants’ persistent diagnosis of ADHD from childhood to emerging adulthood was associated with online social communication usage and quality.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants were 228 females taking part in a longitudinal study. At study entry, which is referred to as Wave 1 (W1), girls were between the ages of 6–12 years (mean = 9.6). Girls were selected because they either met diagnostic criteria for ADHD (n = 140) or formed an age and ethnicity-matched non-ADHD comparison group (n = 88). All girls participated together in 5-week research summer day camps (which were non-academic and not treatment oriented), the details of which are fully described in Hinshaw (2002). Parents, teachers, and girls completed measures to assess functioning across multiple domains. Girls with ADHD and comparison girls were permitted to have other common psychiatric conditions. Exclusionary criteria were IQ less than 70; overt neurological damage, psychosis, or pervasive developmental disorder; and medical conditions that precluded participation in camp. The sample was diverse ethnically (53% White; 27% African American; 11% Latina; 9% Asian American) and socioeconomically, reflecting the San Francisco Bay Area where the data were collected. ADHD and comparison samples did not differ on age, maternal education, ethnicity, family income, or number of parents in the household (Hinshaw, 2002).

A follow-up of the sample was conducted 5 years later, which is referred to as Wave 2 (W2), during which girls were between the ages of 11–18 (mean = 14.1). Parents, teachers, and girls completed measures to report adjustment, although summer camps were not conducted. At least some W2 data were collected from 209 of the original 228 participants (retention = 92%). Further details are provided in Hinshaw et al. (2006). A third follow-up occurred 10 years after the original study enrollment, which is referred to as Wave 3 (W3). Participants were between the ages of 17–24 at this time (mean = 19.6; 20.8% were age 17). We have elected to include the 17 year old participants in order to maximize the sample size, given that emerging adulthood is often described as a general period between “the late teens and mid-twenties” (Arnett, 2000). At W3, measures were collected from participants, parents, and other significant figures (teachers, romantic partners) to assess functioning. At least some data were available at W3 for 216 of the original 228 participants (retention = 95%). See Hinshaw et al. (2012).

Retained participants at W2 and W3 did not differ from those lost to attrition on most demographic and behavioral variables at W1 (no differences on 47 of 54 variables tested), but retained participants were more likely to have come from a two-parent household and to have less psychopathology on some measures at W1, relative to those lost to attrition (see Hinshaw et al., 2006; Hinshaw et al., 2012). In the current study, we considered participants’ childhood ADHD diagnostic status (at W1), as well whether they displayed persistent ADHD (at both W1 and W3), intermittent ADHD (either W1 or W3), or were consistent comparison status (at both W1 and W3) as predictors of online social communication in emerging adulthood (W3).

Measures

W1 ADHD and comorbid diagnoses (predictor and covariate)

ADHD diagnostic status (dichotomous; dummy coded) was rigorously assessed using DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). As an initial screener, girls with ADHD needed to have: (a) at least five of nine inattention symptoms endorsed at a level of 2 (pretty much) or 3 (very much) by both parent and teacher on the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Scales (SNAP-IV; Swanson, 1992), with hyperactivity symptoms ranging from zero through nine endorsed; and (b) T-scores of at least 60 on the Child Behavior Checklist and Teacher Report Form Attention Problem subscales (Achenbach, 1991a, 1991b). However, all girls were requred to have ADHD diagnosis validated on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000), administered to parents (at least six of nine symptoms of inattention required). Comparison girls needed to be below cutoffs on all parent and teacher ratings, and have no diagnosis of ADHD on the DISC-IV, but could have other disorders as well as subclinical manifestations of ADHD. See Table 1 for ADHD symptom counts.

Table 1.

Participant Subtype and Symptom Counts by ADHD Status

| W1 |

W3 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | ADHD (n = 140) |

Comparison (n = 88) |

pa | ADHD (n = 85) |

Comparison (n = 129) |

pa |

| ADHD subtypeb | ||||||

| Inattentive type | 47 | N/A | 39 | N/A | ||

| Combined type | 93 | N/A | 46 | N/A | ||

| Number of inattentive symptomsc | ||||||

| Parent report | 7.7 | 0.6 | < .001 | 7.3 | 1.4 | < .001 |

| Teacher report | 6.0 | 0.3 | < .001 | N/A | N/A | |

| Self-report | N/A | N/A | 6.2 | 1.9 | < .001 | |

| Number of hyperactive/impulsive symptomsc | ||||||

| Parent report | 6.4 | 0.3 | < .001 | 3.6 | 0.8 | < .001 |

| Teacher report | 3.5 | 0.1 | < .001 | N/A | N/A | |

| Self-report | N/A | N/A | 4.2 | 1.4 | < .001 | |

Note. W1 = Wave 1; W3 = Wave 3.

For ADHD versus Comparison groups, independent samples t-tests were performed.

W1 diagnoses were based on DSM-IV; W3 diagnoses on DSM-IV-TR. At W1, girls with the Hyperactive/Impulsive type of ADHD (ADHD-HI) were excluded because of evidence that this subtype is most relevant for preschoolers; see Hinshaw (2002). At W3, four women met criteria for ADHD-HI. The small numbers preclude meaningful analysis, so these participants were added into the ADHD-C group because of the shared presence of hyperactivity/impulsivity; see Hinshaw et al. (2012).

At W1, self-report of symptom counts was not obtained. At W3, teacher report of symptom counts was not obtained.

We used parent report on the DISC-IV to determine comorbid disorders because of the age of the sample at W1; see Hinshaw (2002). Girls were classified as meeting DSM-IV criteria for an internalizing disorder (any depressive or anxiety disorder, with the exception of simple phobias). Of 140 girls with ADHD, 37 were considered to have a comorbid internalizing disorder (0 depression only, 27 anxiety only, 10 both). Among the 88 comparison girls, 3 met criteria for an internalizing disorder (0 depression only, 3 anxiety only, 0 both). Girls were also classified as meeting DSM-IV criteria for a disruptive behavior disorder (oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder; note that DSM-IV does not permit both diagnoses simultaneously). Of 140 girls with ADHD, 91 were considered to have a comorbid disruptive behavior disorder (62 oppositional defiant disorder, 29 conduct disorder). Among the 88 comparison girls, 6 met criteria for a disruptive behavior disorder (6 oppositional defiant disorder, 0 conduct disorder).

W3 ADHD diagnoses (predictor)

At the W3 assessment point, ADHD status was again assessed, using DSM-IV-TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Given the age of the sample at W3, assessments prioritized self-reports. Each of the 18 core ADHD symptoms was considered to be endorsed if either the participant or her parent reported its presence on the SNAP-IV or on the DISC-IV. To be diagnosed with ADHD, participants needed to have a minimum of six of nine symptoms of inattention or six of nine symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity. Symptom counts are also presented in Table 1. See Hinshaw et al. (2012) for an extensive explanation of the diagnostic procedure at this time point. At W3, 85 women met criteria for ADHD and 129 did not.

W3 usage of online communication (criterion measure)

Preference for online communication

This was assessed with a 24-item self-report measure validated in previous research (Szwedo et al., 2011) and originally derived from Morahan-Martin and Schumacher (2003). Items included statements that directly endorsed preferring online methods of communication (sample item: “I prefer communication online to face-to-face communication”) as well as using online social communication to feel better (sample item: “I have gone socializing online to make myself feel better when down or anxious”). However, factor analysis suggested that all the items were best considered to be one factor, and the internal consistency (alpha) in our sample was .93. Participants responded to each item using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). A total score was created by taking the mean of the 24 items.

Interaction with strangers online

This three-item questionnaire asked participants to self-report if they had ever: (a) talked online with someone they met online and only know online; (b) formed a close friendship online with someone they met online and only know online; (c) formed a romantic relationship online with someone they first met online and only know online (Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, 2003). Responses to each item were coded as “yes” = 1 or “no” = 0. Internal consistency was .76. We created a total score by summing the items.

W3 quality of online interactions (criterion measure)

The majority of participants (168 of 208; 81%) reported that they had a Facebook page at W3, a rate which approximates national surveys in this age group (Pew Internet and American Life Project, 2013). Participants with a Facebook page did not differ from those without a page in age, household income, internalizing and disruptive behavior comorbidities, or W3 ADHD diagnostic status; all ps > .05. However, those with a Facebook page were more likely at W1 to have been in the comparison group (88.1% with Facebook) than the ADHD group (75.8% with Facebook); χ2 (df = 1) = 4.87; p = .027. This finding is consistent with previous research noting that, despite no group differences in total amount of time spent in online social communication (Mikami et al., 2010), youth with psychopathology are specifically less likely to use Facebook relative to well-adjusted youth (Ljepava, Orr, Locke, & Ross, 2013; Mikami et al., 2010; Ryan & Xenos, 2011). Rather, youth with psychopathology may be more likely to use anonymous forms of online social communication (such as internet gaming or chat rooms), such that the differences between adjusted and maladjusted youth may not lie in total time spent socializing online but rather in the venues they are using to communicate online (Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, 2003).

The 168 participants with Facebook pages were requested to allow the research team to examine their pages, which involved signing a consent form indicating such permission and accepting a friend request from the Facebook page associated with the study; if participants did not do both, they were considered to not have consented. Granting such permission is nontrivial, and 131 of the 168 (78.0%) provided consent. There were no significant differences between the participants who provided consent and those who did not in terms of ADHD status (W1 or W3), disruptive behavior or internalizing comorbidities, age, or household income (all ps > .05).

Trained research assistants coded the participants’ Facebook pages for quality of interactions on Facebook (e.g., friendship quantity and two indicators of positivity in these friendships). Although study personnel kept coders unaware of participants’ diagnostic status and all other data about the participant, it is possible that some participants may have included this information on their Facebook pages; however this was not noted by any coders on this project. Thirty participant pages were selected at random to be double coded in order to assess inter-rater reliability, calculated by intraclass corrections (ICC; Shrout & Fleiss, 1979). ICC conventions are: below .40 = poor; .40–.59 = fair; .60–.74 = good; .75 and above = excellent (Cicchetti, 1994).

Number of friends

As an indicator of friendship quantity, coders recorded the total number of friends that the participant had on Facebook. The ICC for this variable was .99.

Observed connection

As one indicator of the positivity in online relationships, coders considered the most recent 20 posts from friends on the participant’s Facebook page and recorded the number indicating that the participant and the friend shared a genuine close relationship outside of Facebook. This construct was designed to capture the extent to which the participant was close to the friends with whom she was communicating on Facebook, as opposed to communicating with strangers. For example, posts in which the friend said “see you at dinner” or “wasn’t today’s lecture hilarious?” suggested a connected relationship (ICC = .69). Previous research has found that the number of friends’ connection posts (using this coding system) was correlated with participants’ self-reports that they tend to talk online with the same people whom they often see in person (Mikami et al., 2010).

Our aim was to create a ratio of connection posts to the total number of considered posts. The majority of participants (113 of 131) had 20 or more posts from friends on their page, so we coded the most recent 20 and used this value as the denominator. An additional nine participants had between 10 and 20 posts from friends, so we coded these and used all available posts as the denominator. We did not, however, code connection for those participants (9 of 131) with fewer than 10 posts from friends on their page because we thought this was an insufficient sample of posts and suggested that the participant uses Facebook infrequently.

Observed support

As another indicator of the positivity in online relationships, coders also recorded the proportion of the most recent 20 posts in which friends expressed validation, caring, encouragement, understanding, or compliments to the participant. This variable was intended to capture comments that seemed appropriate for a close to intimate friendship. For example, posts such as “you look pretty,” “love you,” “I miss you so much,” or “I’ll always be there for you” were considered as indicators of support (ICC = .83).

The same post could contain both support and connection, as we consider them to be two different indicators of positive relationship quality, similar to the way in which validation/caring (similar to our support construct) and companionship/recreation (similar to our connection construct) have historically been considered to be different indicators of positivity in face-to-face relationships (Parker & Asher, 1993). For example, “I absolutely loved seeing you yesterday” would be a post containing both support and connection. Parallel to the connection variable, we did not code support for participants with fewer than 10 posts from friends but coded (and took the proportion score for) participants who had at least 10 posts from friends available.

W1/W2 peer impairment composite (mediator)

This variable was a composite score created from indicators of peer problems in face-to-face contexts at W1 and W2. Although a mediator is ideally assessed in between the predictor and the criterion (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002), we argue that the predictor, W1 ADHD diagnosis, predated the W1 assessment of peer problems. That is, W1 ADHD diagnosis was assessed in all cases before girls started the summer program, sometimes several months in advance. During the summer program, participants interacted with previously unacquainted peers, and the W1 measure of peer problems was collected from these peers at the end of the program. In addition, the diagnostic criteria for ADHD require persistent symptoms for 6 months or more, further demonstrating that the ADHD diagnosis predated the W1 measure of peer problems. Creating a composite score of W1 and W2 peer problems allowed us to use peer sociometric nominations, only administered during W1 for logistical reasons but considered to be the gold standard method to assess peer problems (Coie et al., 1982), as part of this mediator variable.

Peer sociometric preference

At the end of the summer program occurring during W1, within each classroom (of 25–27 girls), participants nominated up to three peers whom they “most liked” and “least liked” (Coie et al., 1982). Pictures of classmates were shown to facilitate recall. Proportion scores were created by dividing the number of “most liked” and “least liked” nominations each girl received by the number of peers making nominations. Sociometric preference was calculated by subtracting the proportion score of “least liked” nominations received from the proportion score of “most liked” nominations received; see Blachman and Hinshaw (2002) for validity.

Teacher report of peer acceptance

Participants’ regular classroom teachers at W2 completed questions adopted from Dishion and Kavanagh (2003) and demonstrated to correlate with peer sociometrics. Teachers reported the proportion of classroom peers who “like and accept” and “dislike and reject” the participant on a 1–5 scale (1 = few, less than 25%; 2 = some, 25–49%; 3 = about half, 50%; 4 = most, 51–75%; 5 = almost all, over 75%). The score for “dislike and reject” was subtracted from the score for “like and accept.”

W1 peer sociometric preference and W2 teacher report of peer acceptance were correlated r =.50; p < .001, supporting the creation of a composite. Each was z-scored and then the average of the z-scores was multiplied by −1 to create the composite score of peer problems.

Demographics (covariates)

Because of the diversity in age range as well as household income in our sample and because social media usage may vary based on these factors (Pew Internet and American Life Project, 2013), we controlled for the participants’ age at W3 and their total family income from all sources (reported by their parents at W1).

Data Analytic Plan

To test our first two aims, we conducted analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) procedures with W1 ADHD diagnosis as the predictor, including the covariates of disruptive behavior and internalizing comorbidities, age, and household income. Criterion variables were the W3 measures of self-reported use of online social communication (preference for online communication and interaction with strangers online) and observed quality of online interactions (number of Facebook friends, connection with Facebook friends, and support from Facebook friends). We note that when the covariate of internalizing comorbidity was broken into depressive and anxiety diagnoses separately, results remained the same.

Next, we tested whether peer impairment in face-to-face contexts at W1/W2 mediated the associations between W1 ADHD status and W3 online social communication measures, following the procedures of Preacher and Hayes (2008). We continued to include statistical control of disruptive behavior and internalizing comorbidities, age, and household income in these analyses. For all criterion measures significantly predicted by W1 ADHD diagnostic status in the ANCOVA results (path c), we proceeded to test the relationship between W1 ADHD diagnostic status and the peer impairment composite (path a), and the relationship between the peer impairment composite and the W3 online social communication measure (path b) after statistical control of W1 ADHD diagnostic status. If paths a and b were significant, we retested the association between W1 ADHD status and the W3 online social communication measure after statistical control of the peer impairment composite (path c’), and assessed the indirect effect via bootstrapping with 5000 resamples. If the bias corrected confidence interval around the indirect effect did not include zero, then we considered the conditions for mediation to be met.

There is significant controversy in the field regarding how to assess ADHD in adulthood, and how to classify adults with histories of childhood ADHD who no longer meet criteria for ADHD, as evidence suggests that they continue to demonstrate substantive impairments (Barkley et al., 2008; Hinshaw et al., 2012). To test our final aim, we classified participants into those with persistent ADHD diagnosis (n = 74), intermittent ADHD diagnosis (n = 65; 54 of these were ADHD at W1 and moved to comparison status at W3), and consistent comparison status (n = 75) from W1 to W3, following the procedure used by Swanson, Owens, and Hinshaw (2014). Although the 54 participants who had ADHD at W1 but not at W3 may differ from the 11 participants who had ADHD at W3 but not W1, we consider them together as having intermittent ADHD because the small size of the latter group precludes separate analyses, and because comparison of these groups is not the focus of the current study. We repeated the ANCOVA models predicting W3 online social communication substituting the three group classification in place of childhood (W1) ADHD diagnostic status. All covariates remained the same.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Tables 1 and 2 display descriptive statistics based on ADHD and comparison group status at W1. Because the raw number of Facebook friends was highly positively skewed, we square root transformed this variable to yield an approximately normal distribution. For other variables the skew was minor. Bivariate correlations between all W3 online social communication variables, the potential mediator, and covariates are presented in Table 3. Not surprisingly, a greater history of having interacted with strangers online was associated with a greater stated preference for online communication methods, and these variables tended to be correlated with fewer Facebook friends and less positivity in interactions with Facebook friends.

Table 2.

Demographics, Peer Impairment, and Online Social Communication as Predicted by Childhood ADHD Status

| n | W1 ADHD | W1 Comparison | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | M | SD | M | SD | F | pa | ESb | |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Age in years (W3) | 216 | 19.6 | 1.7 | 19.5 | 1.8 | 0.64 | .423 | .06 |

| Household incomec (W1) | 219 | 6.2 | 2.7 | 6.7 | 2.4 | 2.22 | .138 | .20 |

| Mediator | ||||||||

| Peer impairment composited (W1/W2) | 152 | 0.29 | 0.95 | −0.50 | 0.37 | 34.87 | <.001 | 1.10 |

| Online Social Communication (all at W3) | ||||||||

| Preference for online communication | 189 | 1.85 | 0.54 | 1.66 | 0.391 | 4.27 | .040 | .39 |

| Interaction with strangers online | 194 | 0.94 | 1.14 | 0.37 | 0.70 | 7.65 | .006 | .63 |

| Talk online | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.40 | ||||

| Close friendship online | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.16 | 0.37 | ||||

| Romantic relationship online | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.16 | ||||

| Number of Facebook friendse | 131 | 13.5 | 8.54 | 20.5 | 9.34 | 6.52 | .012 | .80 |

| Connection with Facebook friends | 122 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 6.61 | .011 | .44 |

| Support from Facebook friends | 122 | 0.37 | 0.22 | 0.46 | 0.22 | 4.61 | .034 | .38 |

| Other (all at W3) | ||||||||

| Total time using online social communication | 190 | 7.1 | 3.43 | 6.2 | 2.44 | 2.12 | .065 | .30 |

| Positive peer relationshipsf | 191 | 3.1 | 0.56 | 3.2 | 0.54 | 1.14 | .338 | .23 |

Note. W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3.

p values in this column are listed with covariates in the model for the criterion measures of “online communication” and “other”

Effect sizes are reported as Cohen’s d.

For total annual family income, a value of 1 ≤ $10,000; a value of 9: ≥ $75,000.

This variable is an averaged z-score of the W1 peer sociometric preference measure and W2 teacher report of peer acceptance, multiplied by −1.

This variable was square root transformed to yield an approximately normal distribution.

Assessed on Peer Attachment subscale of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment

Table 3.

Correlations between Online Social Communication and Other Study Variables

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Preference for online communication (W3) |

— | .479** | −.104 | −.174 | −.059 | .425** | .012 | .038 | .280** | −.279** |

| 2. Interaction with strangers online (W3) |

— | −.054 | −.283** | −.278** | .453** | .031 | −.101 | .236** | −.093 | |

| 3. Number of Facebook friendsa (W3) |

— | .082 | .206* | −.239* | −.064 | .074 | .108 | .235** | ||

| 4. Connection with Facebook friends (W3) |

— | .425** | −.316** | .035 | .183* | −.090 | .175 | |||

| 5. Support from Facebook friends (W3) |

— | −.161 | .002 | .129 | −.075 | .138 | ||||

| 6. Peer impairment compositeb (W1/W2) |

— | −.087 | −.117 | .165* | −.582** | |||||

| 7. Age (W3) | — | −.016 | .008 | −.031 | ||||||

| 8. Household income (W1) | — | −.018 | .110 | |||||||

| 9. Total time using online social communication (W3) |

— | .024 | ||||||||

| 10. Positive peer relationshipsc (W3) |

— |

Note. W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3.

This variable was square root transformed to yield an approximately normal distribution.

This variable is an averaged z-score of the W1 peer sociometric preference measure and W2 teacher report of peer acceptance, multiplied by −1.

Assessed on Peer Attachment subscale of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment

p < .05.

p < .01

Childhood ADHD Diagnosis Predicts Use of Online Social Communication

Table 2 presents group differences between emerging adult women with histories of childhood ADHD relative to women with comparison status in childhood on variables indicating usage of online social communication. After statistical control of covariates, W1 ADHD diagnostic status predicted women’s greater stated preference for online communication at W3, with an effect size between small and medium. Women who had childhood ADHD also reported having had more interaction with strangers online, with an effect size between medium and large.

Childhood ADHD Diagnosis Predicts Quality of Online Interactions

As seen in Table 2, we also tested group difference between participants who had ADHD relative to comparison participants at W1 on the criterion variables indicating quality of online interactions. After statistical control of covariates, W1 ADHD status was associated with women having fewer Facebook friends at W3, with a large effect size. In addition, W1 ADHD status predicted less connection and less support observed in friends’ posts on Facebook pages; effect sizes were between small and medium.

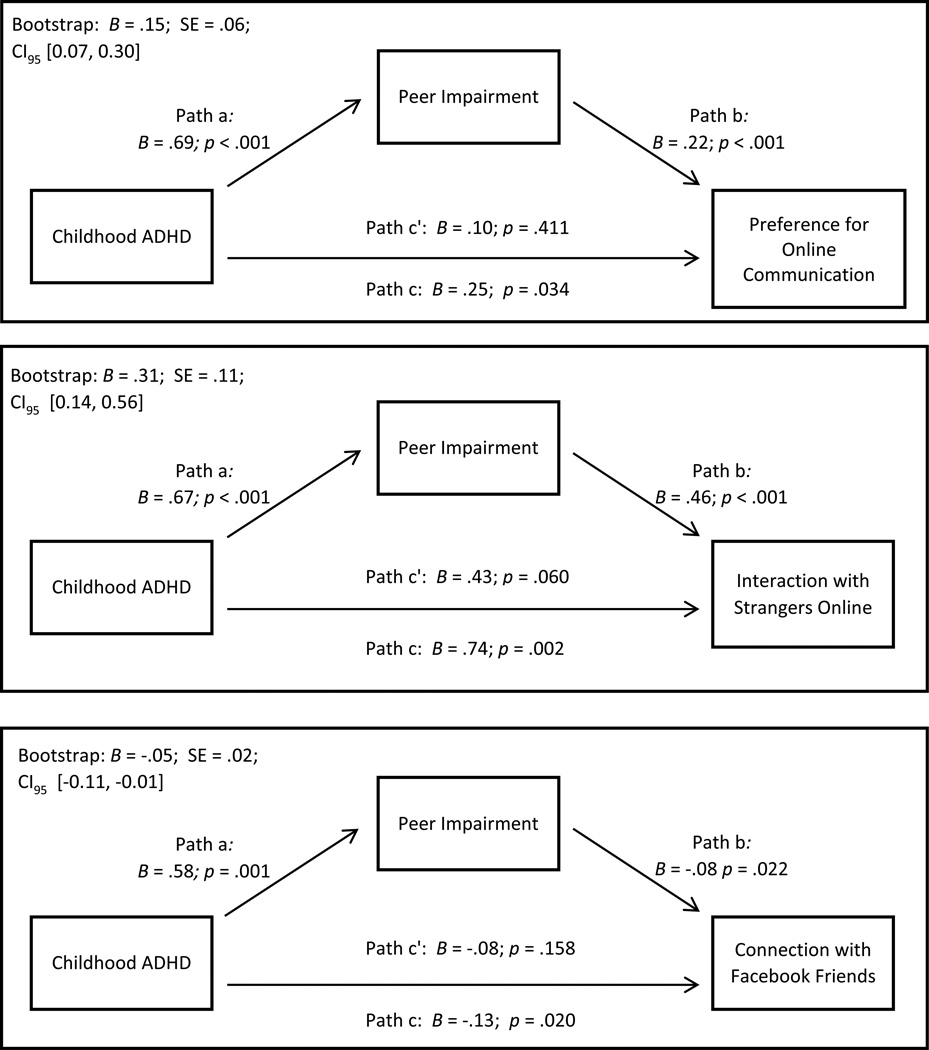

Mediational Models

Given that the associations between childhood ADHD status and all five online social communication criterion variables in emerging adulthood were significant (Table 3), we proceeded to test mediators for each variable. Mediational models had a reduced sample size of 152 for questionnaire measures and 89 for observational measures, because they required the participant to have complete data on the mediator (measured at both W1 and W2). Despite this reduction in sample size, all the significant findings for path c (W1 ADHD predicting W3 online social communication) with the full sample were maintained for the smaller sample. Figure 1 displays findings that the face-to-face peer impairment composite mediated the association between W1 ADHD diagnostic status and the W3 criterion variables of: (a) preference for online communication; (b) interaction with strangers online; and (c) connection with Facebook friends, such that the previously significant c path was reduced to nonsignificance. However, mediation was not demonstrated for the number of Facebook friends or support from Facebook friends; conditions for mediation were not met in each case because the b path (mediator predicting the criterion variable after statistical control of W1 ADHD status) was not significant.

Figure 1.

Child/adolescent peer impairment in face-to-face contexts mediate the association between childhood ADHD diagnosis and emerging-adult online social communication.

Persistent ADHD Diagnosis Predicts Online Social Communication

The omnibus test for persistence of ADHD (persistent ADHD diagnosis versus intermittent ADHD diagnosis versus consistent comparison status from W1 to W3) was significant for all five online social communication criterion variables, as shown in Table 4. Follow up analyses using independent samples t-tests suggested that the women with persistent ADHD had greater stated preference for online social communication, greater degree of having interacted with strangers online, fewer Facebook friends, less connection observed in Facebook friends’ posts, and less support observed in Facebook friends’ posts, relative to women who were consistently comparison status. The women with persistent ADHD also differed from women with intermittent ADHD for the variables of preference for online social communication and interaction with strangers online. However for the variables of number of Facebook friends and connection with Facebook friends, the women with consistent comparison status differed from the women with intermittent ADHD. See Table 4.

Table 4.

Online Social Communication as Predicted by ADHD Diagnostic Persistence

| 1. Persistent ADHD (W1 and W3) |

2. Intermittent ADHD (W1 or W3) |

3. Consistent Comparison (W1 and W3) |

ESb |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure (all at W3) | n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | F | pa | 1–2 | 1–3 | 2–3 |

| Preference for online communication |

60 | 2.5 (0.55) | 54 | 1.6 (0.49) | 69 | 1.7 (0.38) | 6.79 | .001 | 1.7** | 1.7** | .23 |

| Interaction with strangers online |

62 | 1.2 (1.24) | 57 | 0.6 (0.93) | 69 | 0.38 (0.67) | 8.33 | .000 | .55** | .82** | .27 |

| Number of Facebook friendsc |

41 | 14.0 (9.51) | 36 | 13.5 (7.95) | 50 | 21.1 (9.04) | 4.30 | .016 | .06 | .76** | .89** |

| Connection with Facebook friends |

35 | 0.3 (0.18) | 33 | 0.3 (0.14) | 50 | 0.4 (0.20) | 3.34 | .039 | .00 | .52* | .58* |

| Support from Facebook friends |

35 | 0.3 (0.20) | 33 | 0.4 (0.22) | 50 | 0.5 (0.22) | 3.73 | .027 | .48 | .95* | .45 |

Note. W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3

p values in this column are listed for the omnibus F, with covariates in the model.

Effect size is Cohen’s d, reflecting subgroup contrasts. 1 = Persistent ADHD; 2 = Intermittent ADHD; 3 = Consistent Comparison.

This variable was square root transformed to yield an approximately normal distribution.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Exploratory Analyses

Associations between online and face-to-face peer relationships

Assessment of peer relationships in emerging adulthood is fraught with issues. However, given the newness of our online social communication measures, we sought to compare them to participants’ self-reports of their general peer relationships on a widely-used measure in this age group, the Peer Attachment subscale on the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Armsden & Greenberg, 1987). This subscale contains 25 items answered on a 5-point scale (sample items: “My friends understand me”; “I feel my friends are good friends”). Internal consistency in our sample was .94. As can be seen in Table 2, participants with childhood diagnoses of ADHD did not significantly differ from those with comparison status on this measure, although this is not surprising given research that individuals with ADHD underestimate their social problems on self-report scales (Lui et al., 2013). However, as displayed in Table 3, self-reports of good peer relationships on the IPPA were negatively associated with a stated preference for online social communication, and positively associated with the number of Facebook friends.

Quantity of online social communication

Existing research finds little difference between poorly-adjusted and well-adjusted emerging adults with respect to total amount of online social communication use; rather, the differences occur in the ways in which individuals engage online (e.g., preference for online over face-to-face communication, greater interaction with strangers online, poorer interaction quality online, and potentially greater use of anonymous internet sites to communicate as opposed to Facebook; Davila et al., 2012; Mikami et al., 2010; Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, 2003). However, at W3 participants reported the number of hours they spend in a typical day: (a) reading/sending email with friends; (b) instant messaging or communicating in chat rooms with friends; (c) visiting or posting messages on social networking websites; and, (d) checking or updating their own profiles on these sites. The emphasis was on the social communication functions of the internet, to be distinguished from using the internet for work or research. We summed the items (alpha = .72) to create a score for quantity of online social communication use. This variable was not significantly associated with W1 ADHD diagnostic status (see Table 2). When we included this variable as a covariate in our models, three of the five results that were previously significant at the p ≤ .05 level remained so; the other two (for the criterion variables of preference for online communication and observed support from Facebook friends) dropped to significance levels of p < .116.

ADHD subtypes

Preadolescent children with the Combined Type of ADHD (ADHD-C, who display both inattention and impulsivity/hyperactivity) tend to make off-task and hostile comments in peer interactions, whereas children with the Inattentive Type (ADHD-I, who display inattention only) may be disconnected and withdrawn (Carlson & Mann, 2000). It is unclear to what extent such subtype differences remain relevant or stable in adulthood (Willcutt et al., 2012). Table 1 presents the breakdown of participants by subtype. When we substituted ADHD subtype at W1 (ADHD-C versus ADHD-I versus comparison) for the dichotomous variable (ADHD versus comparison), while retaining the same covariates, results for four of the five criterion variables remained significant at the p ≤ .05 level; the one exception was for preference for online communication which dropped to a significance level of p = .120. Participants with childhood diagnoses of ADHD-C and ADHD-I displayed a similar pattern of functioning to one another, which was distinct from that of the comparison group, such that independent samples t-tests revealed no significant group differences between ADHD-C and ADHD-I participants, on any of the five online social communication measures.

Treatment effects

We also re-conducted analyses adding statistical control of medication usage and any psychosocial treatment in the intervening 5 year period between W2 and W3, as reported by parents, following the procedure of Hinshaw et al. (2012). Four of five previously significant results remained significant at the p ≤ .05 level and one, for the criterion variable of number of Facebook friends, dropped to p = .075.

Discussion

In this investigation we extended the limited existing literature about emerging adult women with ADHD by examining social functioning in a medium that is highly relevant for this age group and in the current culture: online social communication. Our major conclusion is that ADHD in childhood predicts differences in women’s usage of online social communication in emerging adulthood (i.e., participants with childhood ADHD were more likely to prefer the online medium and to have interacted with strangers online than comparison women) as well as quality of online interactions on the popular social networking site Facebook (i.e., on Facebook, participants with childhood ADHD had fewer friends, fewer connected relationships with friends, and received less emotional support from friends than comparison women). Moreover, we predicted that a history of peer impairment in face-to-face contexts during childhood and adolescence would explain the predictive links between childhood ADHD and emerging-adult online social communication; stringent mediator tests supported this pathway for three of five criterion variables, reducing the previously obtained pathway between childhood ADHD and emerging-adult online social communication to nonsignificance. All findings were maintained after statistical control of comorbid disruptive behavior and internalizing disorders, with the former known to impair face-to-face relationships in ADHD populations (Pfiffner et al., 2000), and the latter linked to problems in online relationships in community samples of emerging adults (Davila et al., 2012).

Adult women with ADHD have been extremely understudied. Other recent findings (Biederman et al., 2010; Hinshaw et al., 2012) paint a picture of significant impairment in varied domains (e.g., antisocial, addictive, mood, anxiety, and eating disorders; suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury; academic underachievement and low educational attainment) for females with this condition. Our results add online social functioning to this list. We note that the differences found in online social communication usage, such that women with childhood histories of ADHD were more likely to prefer online communication and to have interacted with strangers online, are not necessarily pathological, although previous research tends to find these patterns in poorly adjusted individuals (Birnie & Horvath, 2002; Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, 2003; Subrahmanyam et al., 2008; Szwedo et al., 2011). However, our results suggest that women with childhood ADHD demonstrated poorer quality online interactions in terms of less friendship quantity and positivity in relationships, two metrics consistently used to characterize impairment in face-to-face contexts (Hartup, 1995).

The online social domain may be particularly sensitive to any impairing effects of ADHD for females. Although preadolescent boys and girls with ADHD have equally poor face-to-face peer relationships (Gershon, 2002; Hoza et al., 2005), we speculate that gender differences may be more likely to emerge in the online domain. Online social networking websites pull for witty, verbal, back-and-forth exchanges, in which individuals have to consider self-presentation, given that communication is viewed by all members of the social network (Gosling, 2009; Subrahmanyam et al., 2008). These type of interactions are historically prioritized by (and demonstrated more proficiently by) females (Maccoby, 2002); however, ADHD symptoms disrupt individuals’ ability to follow conversations, pick up on subtle social cues, and contribute to verbal discussions appropriately. Such communication deficits are quite visible in the online social domain, and women with these deficits, as opposed to men, may appear relatively poorer functioning compared to the norm for their gender.

We also found evidence that women with persistent diagnoses of ADHD from childhood to emerging adulthood differed from women who were consistently comparison status on all online social communication measures. Women with intermittent diagnoses of ADHD (the majority of whom had ADHD in childhood but no longer met criteria for this disorder in emerging adulthood) had scores intermediate between women with persistent ADHD status and women with consistent comparison status. These findings may have occurred for several reasons. First, there is controversy in the field about how to diagnose ADHD in adulthood (Barkley et al., 2008). The DSM-IV-TR symptoms may not have been written in such a way to be sensitive to adult presentations of ADHD, and there is lack of consensus about how to consider collateral reports of adults’ symptomatology. Thus, some women no longer meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria for ADHD in emerging adulthood may in fact still have had the disorder, which may explain why the women with intermittent diagnoses of ADHD displayed some similarities in online social communication to those with consistent diagnoses of ADHD.

Another potential explanation is that, regardless of current ADHD diagnosis, having childhood ADHD set girls on a path of poor face-to-face relationships, depriving them of opportunities to learn or to practice social skills such as reading social cues, compromise, and trust (Pedersen et al., 2007). Consequently, they reached emerging adulthood lacking the capacity to engage competently in the online context that is endemic among this age group (Mikami et al., 2010). Our finding that child/adolescent peer problems in face-to-face contexts mediated the prospective association between childhood ADHD status and three of the five criterion variables of online social communication in emerging adulthood lends support to this second interpretation. The bottom line, however, is that even if emerging adult women appear to have outgrown their diagnosis of childhood ADHD, they may not outgrow their social difficulties.

Few differences in online social communication during emerging adulthood were found between women with histories of ADHD-I versus ADHD-C. By contrast, subtype differences in social interaction are more consistently obtained in childhood samples (Carlson & Mann, 2000). Our pattern of results may reflect the general instability of ADHD subtypes, as well as the greater persistence of inattentive relative to hyperactive/impulsive symptoms across the lifespan (Willcutt et al., 2012). In fact, DSM-5 has downgraded ADHD subtypes to current “presentations” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Alternatively, our results may have occurred because the majority of our criterion variables assess positive friendship features (e.g., quantity of friends, connection, and support). Emerging adults with ADHD-C and ADHD-I may equally lack positive interactions, and the subtypes may be better distinguished by the presence of negative interactions in the ADHD-C but not the ADHD-I subtype (Canu et al., 2014).

We lacked inclusion of online social communication measures at time points before W3. This could be considered a limitation; however, including these measures earlier was unrealistic. W1 data were collected in 1997–1999, predating Facebook creation by at least 5 years and widespread adoption outside of college students by 10 years. In addition, at previous time points the girls had not reached the age in which online social communication use becomes common. We argue that online social communication is most relevant for both the current culture (which was not in existence even 10 years ago) and for the age group of emerging adults.

Another limitation concerns attrition. Even though we had high retention rates (92% at W2; 95% at W3), attrition may not have been random. Additional attrition ensued because we required participants to have a Facebook page and consent to the study observing their page. There were suggestions that, similar to other samples (Mikami et al., 2010), better-adjusted participants may have been more likely to have a Facebook page (even if they were no more likely to consent to allow the study to view their page), meaning that our observed measures of Facebook interactions may actually overestimate the functioning in the ADHD sample. Finally, the sample consisted of participants who were willing to attend a research summer day camp in childhood, although all available evidence suggests that these participants were representative of the local population of girls with and without ADHD (Hinshaw, 2002).

Finally, it is important to keep in mind that results from this study regarding Facebook may not generalize to emerging adults’ behavior on other online media, such as online gaming or anonymous chat rooms. In fact, researchers have speculated that Facebook interactions, as opposed to interactions in other online media, may more closely resemble face-to-face relationship patterns (Mikami et al., 2010; Subrahmanyam et al., 2008). One reason might be that individuals are likely to use their real identity on Facebook, and that Facebook is used by the vast majority of emerging adults (Caers et al., 2013).

A significant strength of the study was the involvement of a large sample of females, rigorously diagnosed with ADHD and followed in a longitudinal design. This type of sample is extremely rare. In addition, our measures were multi-method and multi-informant; this applied to the predictors, mediators, and most importantly given the limitations in the existing literature, our criterion measures of Facebook interactions (which were observed). As such, there was nearly complete separation of shared method variance in study analyses.

An intriguing future direction would be to examine whether positive online social relationships in emerging adulthood buffer against maladjustment at later follow-up points. We make this prediction based on findings that high quality face-to-face relationships incrementally contribute to positive adjustment in longitudinal studies of youth with ADHD (Mikami & Hinshaw, 2006; Mrug et al., 2012). Such a result would be in line with findings from a community sample that positive friendship quality on Facebook predicted declines in depression/anxiety over a 1 year period, although only for participants with poor face-to-face relationships (Szwedo, Mikami, & Allen, 2012).

In summary, the current findings document that ADHD in girls may portend poor social functioning 10 years later in emerging adulthood in the relatively new and understudied domain of online social communication. A history of impaired face-to-face peer relationships may explain this finding. Collectively, results underscore the importance of detection and treatment of girls and women with ADHD, even if ADHD symptoms subside in emerging adulthood.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by NIMH grant 45064 to Stephen Hinshaw. We are grateful to the participants and their families, whose assistance made this research possible. We would also like to thank Elizabeth Owens, Christine Zalecki, and many other staff and research assistants for their contributions to the data collection.

Contributor Information

Amori Yee Mikami, University of British Columbia.

David E. Szwedo, James Madison University

Shaikh I. Ahmad, University of California, Berkeley

Andrea Stier Samuels, San Francisco State University.

Stephen P. Hinshaw, University of California, Berkeley

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for child behavior checklist and revised child behavior profile. Burlington, VT: University Associates in Psychiatry; 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for teacher's report form and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University Associates in Psychiatry; 1991b. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. -text revision. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1987;16(5):427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, Molina BSG, Pelham WE, Hoza B. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and problems in peer relations: Predictions from childhood to adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(11):1285–1292. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR, Fischer M. ADHD in adults: What the science says. New York: Guilford; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Petty CR, Monuteaux MC, Fried R, Byrne D, Mirto T, Faraone SV. Adult psychiatric outcomes of girls with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: 11-year follow-up in a longitudinal case-control study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(4):409–417. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnie SA, Horvath P. Psychological predictors of internet social communication. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2002;7(4):0–0. [Google Scholar]

- Blachman DR, Hinshaw SP. Patterns of friendship among girls with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30(6):625–640. doi: 10.1023/a:1020815814973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caers R, De Feyter T, De Couck M, Stough T, Vigna C, Du Bois C. Facebook: A literature review. New Media & Society. 2013;15(6):982–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Canu WH, Carlson CL. Differences in heterosocial behavior and outcomes of ADHD-symptomatic subtypes in a college sample. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2003;6(3):123–133. doi: 10.1177/108705470300600304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canu WH, Tabor LS, Michael KD, Bazzini DG, Elmore AL. Young adult romantic couples’ conflict resolution and satisfaction varies with partner's Attention- Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder type. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2014;40(4):509–524. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carli V, Durkee T, Wasserman D, Hadlaczky G, Despalins R, Kramarz E, Kaess M. The association between pathological Internet use and comorbid psychopathology: A systematic review. Psychopathology. 2012;46(1):1–13. doi: 10.1159/000337971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson CL, Mann M. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, predominately inattentive subtype. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America;Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2000;9(3):499–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(4):284–290. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, Coppotelli H. Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18(4):557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Hershenberg R, Feinstein BA, Gorman K, Bhatia V, Starr LR. Frequency and quality of social networking among young adults: Associations with depressive symptoms, rumination, and corumination. Psychology of Popular Media Culture. 2012;1(2):72–86. doi: 10.1037/a0027512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K. Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. New York: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. The benefits of facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2007;12(4):1143–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Bhatia V, Hershenberg R, Davila J. Another venue for problematic interpersonal behavior: The effects of depressive and anxious symptoms on social networking experience. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2012;31(4):356–382. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Methods and measures: The network of relationships inventory: Behavioral systems version. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33(5):470–478. doi: 10.1177/0165025409342634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaub M, Carlson CL. Gender differences in ADHD: A meta-analysis and critical review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(8):1036–1045. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199708000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon J. A meta-analytic review of gender differences in ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2002;5(3):143–154. doi: 10.1177/108705470200500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling S. The ancient psychological roots of Facebook behavior. Harvard Business Review. 2009 Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2009/03/the-ancient-psychological-root.html.

- Hartup WW. The three faces of friendship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1995;12(4):569–574. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP. Preadolescent girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: I. Background characteristics, comorbidity, cognitive and social functioning, and parenting practices. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(5):1086–1098. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.5.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Owens EB, Sami N, Fargeon S. Prospective follow-up of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into adolescence: Evidence for continuing cross-domain impairment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(3):489–499. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Owens EB, Zalecki C, Huggins SP, Montenegro-Nevado AJ, Schrodek E, Swanson EN. Prospective follow-up of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into early adulthood: Continuing impairment includes elevated risk for suicide attempts and self-injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(6):1041–1051. doi: 10.1037/a0029451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Mrug S, Gerdes AC, Hinshaw SP, Bukowski WM, Gold JA, Arnold LE. What aspects of peer relationships are impaired in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(3):411–423. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner R, Gavin J, Duffield J, Brosnan M, Crook C, Durndell A, Lovatt P. Gender, internet identification, and internet anxiety: Correlates of internet use. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2005;8(4):371–378. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2005.8.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Shaw D. Developmental and social influences on young girls' early problem behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121(1):95–113. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RG, Mannuzza S, Olazagasti MAR, Belsky ER, Hutchison JA, Lashua-Shriftman E, Castellanos FX. Clinical and functional outcome of childhood ADHD 33 years later. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(12):1295–1303. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut R, Kiesler S, Boneva B, Cummings J, Helgeson V, Crawford A. Internet paradox revisited. Journal of Social Issues. 2002;58(1):49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kraut R, Patterson M, Lundmark V, Kiesler S, Mukophadhyay T, Scherlis W. Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist. 1998;53(9):1017–1031. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.9.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljepava N, Orr RR, Locke S, Ross C. Personality and social characteristics of Facebook non-users and frequent users. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(4):1602–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Lui JH, Johnston C, Lee CM, Lee-Flynn SC. Parental ADHD symptoms and self-reports of positive parenting. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(6):988–998. doi: 10.1037/a0033490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Gender and social exchange: A developmental perspective. In: Laursen B, Graziano WG, editors. Social Exchange in Development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 87–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami AY. The importance of friendship for youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2010;13(2):181–198. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0067-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami AY, Hinshaw SP. Resilient adolescent adjustment among girls: Buffers of childhood peer rejection and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34(6):823–837. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9062-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami AY, Szwedo DE, Allen JP, Evans MA, Hare AL. Adolescent peer relationships and behavior problems predict young adults’ communication on social networking websites. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(1):46–56. doi: 10.1037/a0017420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D, Becker-Blease KA. Classification of adults with problematic internet experiences: Linking internet and conventional problems from a clinical perspective. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2007;10(3):381–392. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morahan-Martin J, Schumacher P. Loneliness and social uses of the Internet. Computers in Human Behavior. 2003;19(6):659–671. [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, Molina BG, Hoza B, Gerdes A, Hinshaw S, Hechtman L, Arnold LE. Peer rejection and friendships in children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Contributions to long-term outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40(6):1013–1026. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9610-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y. Social anxiety, Internet use and personal relationships on the Internet. The Japanese Journal of Social Psychology. 2003;19(2):124–134. [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Asher SR. Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(4):611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S, Vitaro F, Barker ED, Borge AIH. The timing of middle-childhood peer rejection and friendship: Linking early behavior to early-adolescent adjustment. Child Development. 2007;78(4):1037–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pempek TA, Yermolayeva YA, Calvert SL. College students' social networking experiences on Facebook. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2009;30(3):227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Internet and American Life Project. Social networking fact sheet. 2013 Retrieved May 23, 2014, from http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/social-networking-fact-sheet/

- Pfiffner LJ, Calzada E, McBurnett K. Interventions to enhance social competence. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America;Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2000;9(3):689–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T, Xenos S. Who uses Facebook? An investigation into the relationship between the Big Five, shyness, narcissism, loneliness, and Facebook usage. Computers in Human Behavior. 2011;27(5):1658–1664. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon P. Voices that cannot be heard: Can shyness explain how we communicate on Facebook versus face-to-face? Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(4):1402–1407. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86(2):420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam K, Garcia ECM, Harsono LS, Li JS, Lipana L. In their words: Connecting on-line weblogs to developmental processes. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2009;27(1):219–245. doi: 10.1348/026151008x345979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam K, Reich SM, Waechter N, Espinoza G. Online and offline social networks: Use of social networking sites by emerging adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2008;29(6):420–433. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson EN, Owens EB, Hinshaw SP. Pathways to self-harmful behaviors in young women with and without ADHD: A longitudinal examination of mediating factors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55(5):505–515. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JM. Assessment and treatment of ADD students. Irvine, CA: K.C. Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Szwedo DE, Mikami AY, Allen JP. Qualities of peer relations on social networking websites: Predictions from negative mother-teen interactions. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(3):595–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00692.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szwedo DE, Mikami AY, Allen JP. Social networking site use predicts changes in young adults’ psychological adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2012;22(3):453–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00788.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Preadolescents' and adolescents' online communication and their closeness to friends. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(2):267–277. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Social consequences of the Internet for adolescents: A decade of research. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt EG, Nigg JT, Pennington BF, Solanto MV, Rohde LA, Tannock R, Lahey BB. Validity of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom dimensions and subtypes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(4):991–1010. doi: 10.1037/a0027347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolak J, Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D. Escaping or connecting? Characteristics of youth who form close online relationships. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26(1):105–119. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(02)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen J-Y, Yen C-F, Chen C-S, Tang T-C, Ko C-H. The association between adult ADHD symptoms and internet addiction among college students: The gender difference. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2009;12(2):187–191. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]