Highlights

-

•

We present a case of giant lipoma in the left lumbar region.

-

•

Movements were hindered, especially rotation, flexion and extension of the trunk.

-

•

The size of the bulk presents differential diagnostic problems with liposarcoma.

-

•

Surgical excision was performed to confirm diagnosis with histological evaluation.

Keywords: Giant lipoma, Left lumbar region, Differential diagnosis, Liposarcoma

Abstract

Introduction

Lipomas are the most common benign tumors of the adipose tissue and can be located in any region of the body. In most cases lipomas are small and asymptomatic, but they can at times reach considerable dimensions and, depending on their anatomic site, hinder movements, get inflamed, cause lymphedema, pain and/or a compression syndrome.

Presentation of case

We here report the case of an otherwise healthy patient who came to our observation with a giant bulk in the left lumbar region which had been showing progressive growth in the previous 5–6 years. Physical examination, ultrasound and MRI were carried out in order to characterize the size, vascularization and limits of the lesion. Due to the pain and restriction of movement that this bulky lesion caused, surgical excision of the lesion was performed.

Discussion

Giant lipomas display an important differential diagnosis problem with malignant neoplasms, especially liposarcomas, with which they share many features; often the final diagnosis rests on histological evaluation. We here discuss the diagnostic problems that arise with a giant lipoma and all the possible approaches concerning treatment of such a big lesion, explaining the reasons of our approach and management of a common tumor in our case presenting unusual dimensions and location.

Conclusion

Our approach revealed to be successful in order to nurse our patient's pain, restore the mobility and address the aesthetic issues that this lesion caused. Postoperative checkups were carried out for one year and no signs of relapse have been reported.

1. Introduction

Lipomas are the most common benign tumors of the adipose tissue and can be located in any region of the body [1]. They are well differentiated neoplasms, consisting of adipocytes surrounded by a fibrous capsule, palpable as soft subcutaneous bulks [2] not painful to the touch. In most cases lipomas are small [4], asymptomatic and they do not evolve into malignant tumors [15,16], but they can at times reach considerable dimensions and, depending on their anatomic site, hinder movement, get inflamed, cause lymphedema, pain and/or a compression syndrome [1,5–8].

Sanchez et al. [2] defined the giant lipoma as a lesion that is over 10 cm in maximum diameter or that weighs over 1000 g.

We here report the case of a patient who came to our observation with a 23 × 11 × 8 cm lipoma in the left lumbar region. Therefore we describe the approach and management of a common tumor presenting quite unusual dimensions and location.

2. Presentation of case

A 32-year-old woman came to our observation complaining the appearance of a subcutaneous bulk in the left lumbar region, which had been showing progressive growth in the previous 5–6 years.

The remarkable size of the bulk caused pain and restriction of movement, especially flexion, extension and rotation of the trunk, besides constituting a serious aesthetic issue.

The patient was otherwise healthy, did not take any kind of medication and did not refer previous similar episodes. Her parents and her two siblings (a male and a female) enjoyed good health and did not report any similar lesions. The patient weighed 92 kg and was 170 cm tall; she had a BMI of 31.8, being therefore in the obesity range. She referred undergoing a low-calorie diet during the years prior to the examination, resulting in a weight loss of approximately 20 kg, contributing to draw attention to the bulky lesion in her left flank.

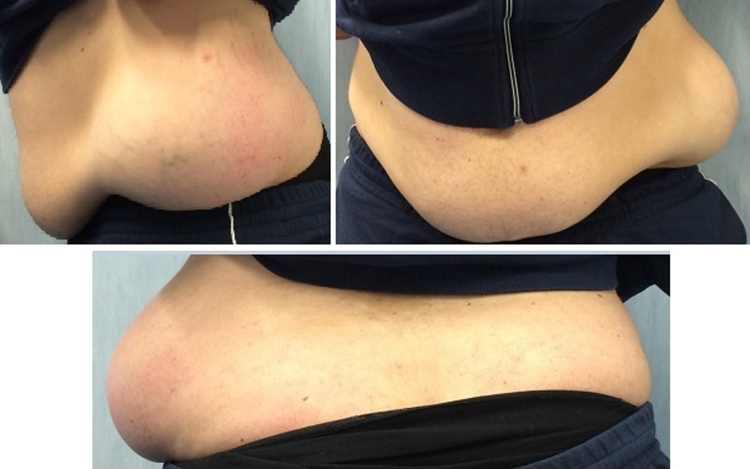

Inspection was carried out with patient undressed in both standing and supine position. It revealed the presence of a voluminous mass that altered the physiological silhouette of the left flank. The skin overlying the lesion appeared normochromic and normotrophic (Fig. 1). Palpation of the left lumbar region revealed a subcutaneous bulk, which was painful to the touch but mobile on the underlying planes.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative study of the case: inspection reveals a voluminous mass in the left lumbar region that alters its physiological silhouette. The skin overlying the bulk appears normochromic and normotrophic.

Routine lab tests were normal. The lipid profile also showed normal values. Ultrasound of the left lumbar region and MRI of the abdomen were prescribed in order to better characterize the size, vascularization and limits of the lesion.

Ultrasounds of the left lumbar region showed the presence of an oval, echogenic and non-homogeneous image with fibrolipomatous aspect, measuring approximately 210 × 49 mm.

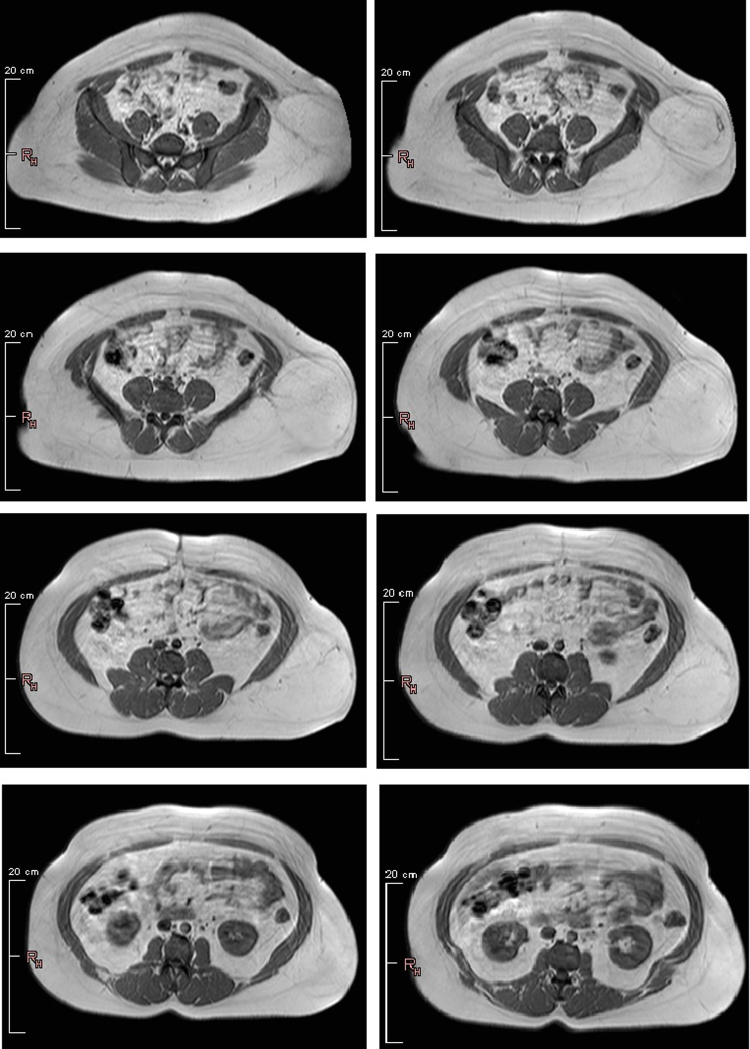

Similarly, MRI of the abdomen showed in the left lumbar region, subcutaneously, a round bulk with regular and sharp edges, a maximum diameter measuring 22 cm and a lipomatous signal. No signs of infiltration of the abdominal wall and muscles underlying the bulk were shown (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

MRI of the abdomen showed at the level of the left lumbar region, subcutaneously, a round bulk with regular and sharp edges, a diameter measuring 22 cm and a lipomatous signal. No signs of infiltration of the abdominal wall and muscles underlying the bulk were shown.

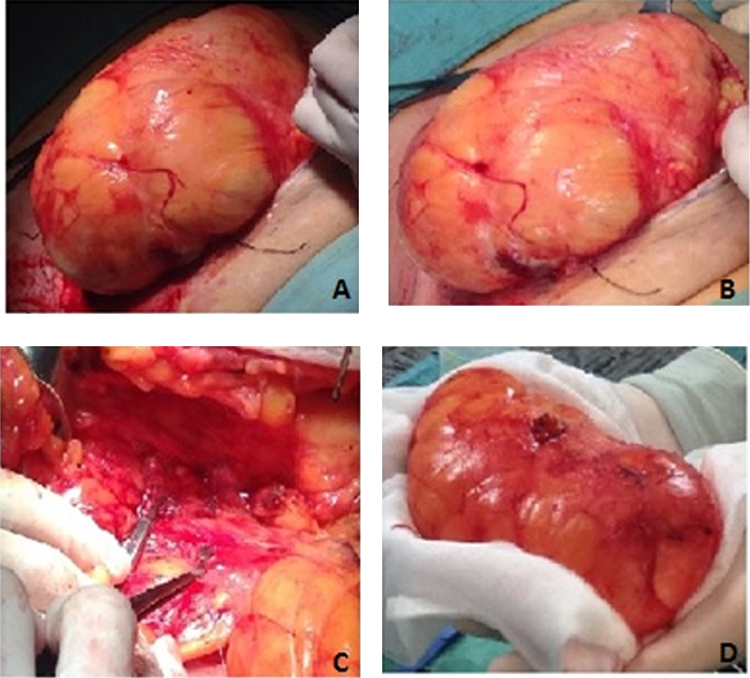

The surgery was carried out in general anesthesia because of the significant size of the lesion. A lozenge incision of the skin above the lesion was performed. After identifying the fibrotic capsule enfolding the mass, the lesion was separated from the layers surrounding it, while paying attention not to disrupt the capsular continuity. A big pedicle leading into the lesion was identified and then ligated before excising the lesion (Fig. 3). After the excision an accurate hemostatis was performed and a drainage tube was positioned. The surgery ended with suture of anatomic layers. Such a big lesion had stretched the skin over it, but the lozenge incision allowed the removal of excess skin. A compressive bandage was applied for four weeks.

Fig. 3.

(A, B) The mass has been separated from the underlying planes while paying attention not to disrupt the capsular continuity. (C) A big vascular peduncle nourishing the bulk was identified and it has been clamped and tied before excising the lesion. (D) Mass after excision.

We prescribed to the patient analgesics to the need and cefazolin immediately after the surgery and twice on the next day. The drainage bag showed traces of serum and blood. The drainage tube has been removed two days after surgery.

Postoperative examinations were uneventful, no hematomas, cutaneous infections or pain were detected.

The macroscopical examination of the excised lesion showed a nodular bulk measuring 23 × 11 × 8 cm with homogeneous adipose features. Histological evaluation confirmed that the lesion was composed of adipose tissue without any signs of cellular atypia. Immunostaining for vimentin and S-100 protein was positive. The FISH for MDM-2 and CDK4 was negative, enabling us to rule out liposarcoma [3] and leading to the final diagnosis of a giant lipoma.

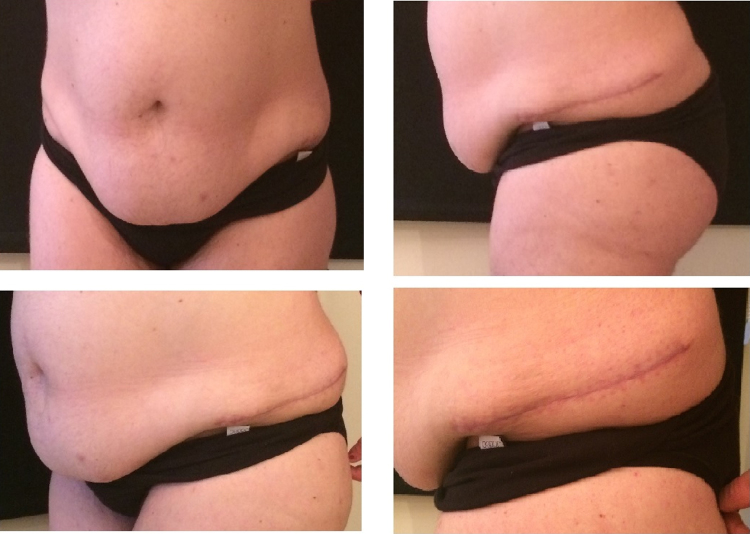

After discharge, the patient underwent follow ups over one year, consisting in physical examination and ultrasounds of the left lumbar region, which showed no signs of a relapse (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Postoperative checkup three months after surgery: the flexion, extension and rotation movements of the trunk have been restored and patient refers that the pain has been solved; the left flank silhouette is now physiological. No signs of relapse have been identified.

3. Discussion

Lipomas are the most common benign tumors of the adipose tissue. They are well differentiated neoplasms, consisting of adult adipocytes [9] surrounded by a fibrous capsule. In most instances they have a subcutaneous localization, but they also have been reported in various internal organs such as liver, kidneys and lungs, where there is no or very little adipose tissue [5]. Giant lipomas are most likely located in internal organs rather than subcutaneously because visceral lipomas are not visible from the outside therefore they grow until they reach considerable dimensions [7,9,10] and eventually compress neighboring structures.

Lipomas are believed to arise from mesenchymal primordial fatty tissue cells. Therefore, they are not of adult fat cell origin. They tend to increase in size with increasing body weight, but interestingly, weight loss usually does not decrease their size. Thus, it appears that they are not available for metabolism even in starvation [4,7].

Very little is known about the pathogenesis of lipomas. An increased incidence is associated with obesity, diabetes, increase of serum cholesterol, radiation, familial tendency and chromosomal abnormalities [9–11].

Trauma is thought to be an important factor in the pathogenesis of lipoma [12]. It has been proposed that rupture of the fibrous septa after trauma accompanied by tears of the anchorage may result in proliferation of adipose tissue [13]. It also has been assumed that local inflammation secondary to trauma may induce differentiation of pre-adipocytes and disrupt the normal regulation of adipose tissue [12,14].

The main problem in the diagnosis of giant lipomas is to rule out malignant neoplasms, especially liposarcomas [14]. The possibility of the lesion being a lipoblastoma, lymphangioma, lymphangiolipoma [15,16] or epidermoid cyst [2] should also be considered.

Well-differentiated liposarcomas have several features in common with benign lipomas: they present as palpable bulks with a variable consistency, generally not painful to the touch. Clinical features suggesting the malignancy of a fatty subcutaneous tumor are a diameter greater than 10 cm, rapid growth of the mass in recent months [4] and deep lesions not being mobile to the underlying tissue. In these cases the possibility of liposarcoma must be considered.

MRI could also not be decisive in order to formulate an exact diagnosis because both the aspect and the low reception of the contrast agents represent common features between lipomas and well-differentiated liposarcomas. In these cases the final diagnosis rests on histopathologic evaluation [5], which allows the assessment of mitotic activity, cellular atypia, necrosis and invasion of contiguous tissues [17,18].

Immunostaining is scarcely helpful for the diagnosis of liposarcoma: vimentin and S-100 protein are positive both in lipoma and liposarcoma. The FISH is a fundamental tool for the diagnosis of liposarcoma. The amplification of MDM-2 and CDK4, located in the chromosomal region 12q14–15, is indeed strongly suggestive of liposarcoma because these genes aren't amplified in lipomas or in the majority of soft tissue sarcomas [3].

Besides surgical excision, it is possible to remove lipomas by using liposuction [14,19,20], which has the advantage of leaving very small scars; however, the application of this technique is restricted by tissue density, localization of the lesion and especially by the impossibility to accurately remove the fibrous capsule, predisposing the patient to relapses. Furthermore, the complications of this technique such as hematomas, nerve damage and blood vessels’ rupture during blind aspiration are not to be neglected.

Conversely, surgical excision not only allows for removing the whole capsule, but it also permits to run a histological exam in order to better characterize the lesion. It is therefore by far the most preferred technique for the removal of lipomas.

Our patient was mostly asymptomatic save for the pain and the restriction of movement of the trunk caused by the magnitude of the mass. Considering the remarkable size of the bulk and therefore the necessity to run a histological exam in order to rule out a liposarcoma, the surgical excision technique was preferred.

Hence, we removed the mass in order to restore the degrees of freedom in flexion, extension and rotation of the trunk, resolve the pain, the physical discomfort and re-establish the physiological silhouette of the left flank.

4. Conclusions

Predisposing factors and aetiopathogenetic mechanisms underlying the development of lipomas are at date still not very clear.

The diagnosis is frequently based on clinical manifestations. However, if a small, palpable subcutaneous mass, not painful to the touch and mobile on underlying planes strongly suggests a benign lipoma, the same cannot be said for a big bulk like the one encountered in our patient.

In conclusion, considering the patient’s disorders, the size of the mass, its unusual site and the differential diagnosis problems with liposarcoma, we considered surgical excision to be the preferred technique in this case.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

The patient who is the subject of our study donated her consensus to scientific treatment and publication of her clinic situation and images. We have obtained written consent from the patient and we can provide it should the Editor ask to see it. This study was approved by our Internal Ethical Committee (Second University Ethical Committee).

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Giuseppe Andrea Ferraro: has contributed to the plan of the study design, he has operated the patient as first surgeon.

Rosa Salzillo: has written this paper, has executed data analysis and data collections.

Francesco De Francesco: has contributed to the clinical management of the patient and the correction and direction of the study.

Francesco D’Andrea: has contributed to the supervision of the surgical management of the patient.

Gianfranco Nicoletti: has contributed to the plan of the study design and the correction anddirection of the study.

Guarantor

Giuseppe Andrea Ferraro.

References

- 1.Hakim E., Kolander Y., Meller Y., Moses M., Sagi A. Gigantic lipomas. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1994;94:369–371. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199408000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanchez M.R., Golomb F.M., Moy J.A., Potozkin J.R. Giant lipoma: case report and review of the literature. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1993;28(2 Pt 1):266–268. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binh M.B., Sastre-Garau X., Guillou L., de Pinieux G., Terrier P., Lagacé R., Aurias A., Hostein I., Coindre J.M. MDM2 and CDK4 immunostainings are useful adjuncts in diagnosing well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcoma subtypes: a comparative analysis of 559 soft tissue neoplasms with genetic data. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2005;29(10 October):1340–1347. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000170343.09562.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terzioglu A., Tuncali D., Yuksel A., Bingul F., Aslan G. Giant lipomas: a series of 12 consecutive cases and a giant liposarcoma of the thigh. Dermatol. Surg. 2004;30(3):463–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di B., enedetto G., Aquinati A., Astolfi M., Bertani A. Giant compressing lipoma of the thigh. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004;114:1983–1985. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000143929.24240.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerrissi J., Klersfeld D., Sampietro G., Valdivieso J. Limitation of thigh function by a giant lipoma. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1994;94:410–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phalen G.S., Kendrick J.I., Rodriguez J.M. Lipomas of the upper extremity: a series of fifteen tumors in the hand and wrist and six tumors causing nerve compression. Am. J. Surg. 1971;121:298–306. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(71)90208-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgs P.E., Young V.L., Schuster R., Weeks P.M. Giant lipomas of the hand and forearm. South Med. J. 1993;86:887–890. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199308000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kshirsagar A.Y., Nangare N.R., Gupta V., Vekariya M.A., Patankar R., Mahna A., Wader J.V. Multiple giant intra abdominal lipomas: a rare presentation. Int. J. Surg Case Rep. 2014;5(7):399–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ilhan H., Tokar B., Is¸ iksoy S., Koku N., Pasaoglu O. Giant mesenteric lipoma. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1999;34:639–640. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss S.W., Goldblum J.R. 5th ed. Mosby; St Louis, MO: 2007. Enzinger and Weiss's Soft Tissue Tumors. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Copcu E., Sivrioglu N.S. Posttraumatic lipoma: analysis of 10 cases and explanation of possible mechanisms. Dermatol. Surg. 2003;29:215–220. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meggitt B.F., Wilson J.N. The battered buttock syndrome–fat fractures: a report on a group of traumatic lipomata. Br. J. Surg. 1972;59:165–169. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800590302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura Y., Teramoto Y., Sato S., Yamada K., Nakamura Y., Fujisawa Y., Fujimoto M., Otsuka F., Yamamoto A. Axillary giant lipoma: a report of two cases and published work review. J. Dermatol. 2014;41(9 September):841–844. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucas D.R., Nascimento A.G., Sanjay B.K., Rock M.G. Well differentiated liposarcoma: the Mayo Clinic experience with 58 cases. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1994;102:677–683. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/102.5.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munk P.L., Lee M.J., Janzen D.L. Lipoma and liposarcoma: evaluation using CT and MR imaging. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1997;169:589–594. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.2.9242783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simsek T., Sonmez A., Aydogdu I.O., Eroglu L. Giant fibrolipoma with osseous metaplasia on the thigh. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2011;64:125–127. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basmaci M., Hasturk A.E. Giant occipitocervical lipomas: evaluation with two cases. J. Cutan. Aesthet. Surg. 2012;5:207–209. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.101387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubenstein R., Roenigk H.H., Jr., Garden J.M., Goldberg N.S., Pinski J.B. Liposuction for lipomas. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 1985;11:1070–1074. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1985.tb01395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nichter L.S., Gupta B.R. Liposuction of giant lipoma. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1990;24:362–365. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199004000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]