SUMMARY

The evolutionary origins of complex morphological structures such as the vertebrate eye or insect wing remain one of the greatest mysteries of biology. Recent comparative studies of gene expression imply that new structures are not built from scratch, but rather form by co-opting preexisting gene networks. A key prediction of this model is that upstream factors within the network will activate their preexisting targets (i.e. enhancers) to form novel anatomies. Here, we show how a recently derived morphological novelty present in the genitalia of D. melanogaster employs an ancestral Hox-regulated network deployed in the embryo to generate the larval posterior spiracle. We demonstrate how transcriptional enhancers and constituent transcription factor binding sites are used in both ancestral and novel contexts. These results illustrate network co-option at the level of individual connections between regulatory genes, and highlight how morphological novelty may originate through the co-option of networks controlling seemingly unrelated structures.

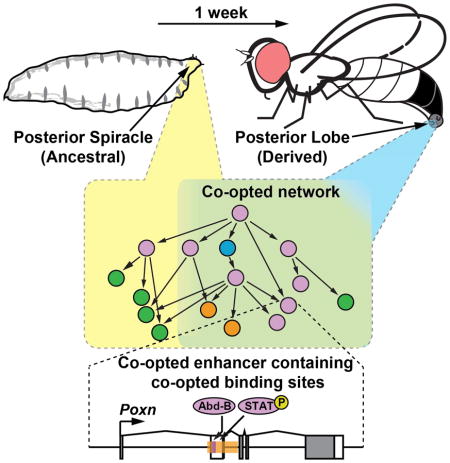

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

“structural genes are building stones which can be used over again for achieving different styles of architecture…evolution is mostly the reutilization of essentially constituted genomes”

Evolutionary biologists have long been intrigued by the origins of biological complexity. While the complexity of living systems can be considered at multiple levels of organization (e.g. the origins of DNA-based life (Crick, 1968; Orgel, 1968), organelles (Sagan, 1967), or multicellularity (Bonner, 1998)), the evolutionary origin of morphological complexity is a developmental problem (Muller and Wagner, 1991). Morphological structures are patterned and formed during the process of embryonic development, and each cell in the developing organism must derive unique physical properties from an identical DNA code. This apparent paradox is solved by differential gene activity, governed by vast gene regulatory networks (GRNs) (Davidson, 2001). Regulatory factors within GRNs bind transcriptional regulatory sequences such as enhancers to combinatorially determine the expression status of each gene of the network in morphological space and developmental time (Small et al., 1992). Hence, an understanding of the origins of morphological complexity necessitates investigations into how GRNs originate.

A growing body of evidence has implicated the re-use, or co-option, of existing networks in the evolution of novel morphological structures (Gao and Davidson, 2008; Keys et al., 1999; Kuraku et al., 2005; Moczek and Nagy, 2005). For example, expression of the appendage-patterning network within the developing beetle horn suggests that this novelty arose through the establishment of a new proximo-distal axis (Moczek and Nagy, 2005; Moczek and Rose, 2009; Moczek et al., 2006). Such findings evoke a scenario in which a cohort of downstream appendage enhancers were in turn activated in the new setting, generating a unique developmental output. However, instances of co-option have traditionally been supported by correlations in gene expression, relationships that may arise without the reuse of existing circuits (Abouheif, 1999). Currently, examples that illustrate this phenomenon at the level of enhancers and the constituent binding sites that were co-opted are lacking.

Here, we trace the evolutionary history of the posterior lobe, a recently evolved morphological structure present in the model organism Drosophila (D.) melanogaster at the level of its network, enhancers, and the transcription factor binding sites of which these are composed.

RESULTS

The posterior lobe is a morphological novelty unique to the D. melanogaster subgroup

Male genitalia represent the most rapidly evolving morphological structures in the animal kingdom (Eberhard, 1985), and are often used to taxonomically distinguish insect species. The posterior lobe is a hook-shaped outgrowth unique to the external genitalia of D. melanogaster and its closest relatives in the melanogaster clade (Figure 1) (Jagadeeshan and Singh, 2006; Kopp and True, 2002). A cuticular projection similar to the posterior lobe is also present in the yakuba clade (Yassin and Orgogozo, 2013), suggesting a recent origin of this structure in the melanogaster subgroup (Figure S1). Among members of the melanogaster clade, the posterior lobe is highly divergent in shape and size, and represents the only reliable character to distinguish species identity (Coyne, 1993). During mating, the posterior lobe is used by the male to grasp the female ovipositor (Jagadeeshan and Singh, 2006), and subsequently is inserted between cuticular plates at the posterior of the female abdomen during genital coupling (Robertson, 1988). Given the recent evolution of the posterior lobe, and its presence in D. melanogaster, a highly tractable model organism for studying the structure and evolution of gene regulatory networks, we sought to elucidate its evolutionary origins.

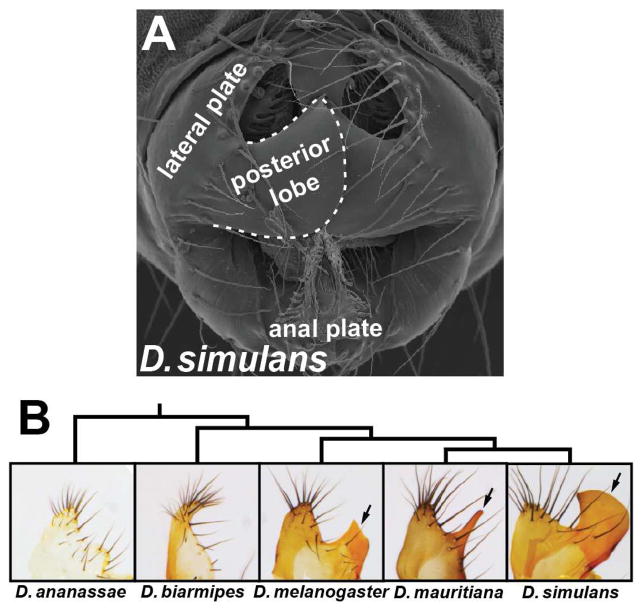

Figure 1.

The posterior lobe is a morphological novelty unique to the D. melanogaster clade. (A) Scanning electron micrograph of a D. simulans male with relevant structures labeled. (B) Tree depicting the phylogenetic relationships of the species in this study, and brightfield images of their lateral plate cuticle morphologies. The posterior lobe is an outgrowth of the lateral plate unique to the melanogaster clade (arrows). See also Figure S1.

An ancestral enhancer of Pox neuro was co-opted into the posterior lobe network

To trace the evolutionary history of the posterior lobe, we first examined Pox neuro (Poxn), a gene that is critical to its development. Poxn encodes a paired-domain transcription factor required for proper posterior lobe formation (Boll and Noll, 2002). In a comprehensive survey of the regulatory region of Poxn, a segment spanning the second exon and intron (Figure 2A) was found to be required for posterior lobe development (Boll and Noll, 2002). To examine the role of this enhancer in genital development and identify how this role evolved, we cloned this segment of the D. melanogaster Poxn gene into a Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) reporter construct (Figure 2A). Transgenic animals bearing the genital enhancer of Poxn drive expression both before and during posterior lobe development. At 32 hours after puparium formation (hAPF), a time that precedes the formation of the posterior lobe (see Figure S2A–L for a time course of genital development in lobed and non-lobed species), we observed broad GFP expression in a zone that straddles the presumptive clasper and lateral plate (Figure 2D). As the posterior lobe emerges from the lateral plate, and assumes its adult morphology, the reporter expresses high levels of GFP in the developing lobe (Figure 2E, arrow). This portion of the Poxn regulatory region accurately recapitulates the endogenous expression of Poxn mRNA and protein in the D. melanogaster lateral plate (Figure 2B–C; Figure S2M–N).

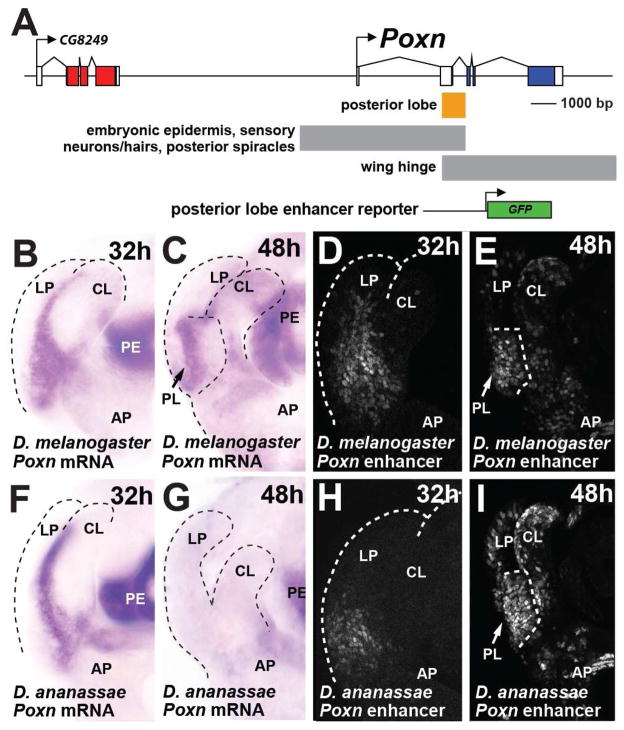

Figure 2.

A deeply conserved enhancer of Poxn is required for posterior lobe development. (A) Schematic of the Poxn locus, displaying a subset of the described enhancer activities (Boll and Noll, 2002), and indicating the relative position of a posterior lobe reporter construct. (B, C) Accumulation of Poxn mRNA during genital development of D. melanogaster at (B) 32 hAPF and (C) 48 hAPF. (D, E) Activity of the D. melanogaster posterior lobe reporter at (D) 32 hAPF and (E) 48 hAPF. (F–G) Expression of Poxn in D. ananassae showing mRNA accumulation in the region between clasper and lateral plates (F), but not at the site where a lobe would develop (G). (H, I) Despite the absence of a posterior lobe in D. ananassae, the orthologous posterior lobe enhancer region drives expression preceding (H) and during posterior lobe development of D. melanogaster (I). CL clasper; LP lateral plate; AP anal plate, PE penis, PL posterior lobe. See also Figure S2.

The high level of reporter and Poxn mRNA in the developing posterior lobe strongly suggests that Poxn plays a direct role during posterior lobe development. To examine how this role evolved, we first analyzed its expression in species that lack this structure. At 32 hAPF, the early pattern of Poxn expression in the non-lobed species D. ananassae greatly resembles that of D. melanogaster prior to posterior lobe formation (Figure 2F). However, Poxn expression quickly subsides in the D. ananassae lateral plate once it has separated from the clasper (Figure 2G). Similar results were obtained for two additional non-lobed species, D. biarmipes and D. pseudoobscura (Figure S2M–N), suggesting that late, high levels of Poxn expression are uniquely associated with the development of this novelty.

Differences in Poxn expression between lobed and non-lobed species may be due to changes in the posterior lobe enhancer region (i.e. in cis), or could be caused by changes in trans that altered upstream regulators in the genitalia (Wittkopp, 2005). To distinguish between these possibilities, and ascertain whether the posterior lobe enhancer of Poxn recently derived its function, we examined the activity of this enhancer from species that lack this structure. Sequences orthologous to the D. melanogaster posterior lobe enhancer region were cloned from several non-lobed species, and tested for the ability to drive GFP reporter expression in the D. melanogaster posterior lobe. The posterior lobe enhancer regions of D. ananassae, D. yakuba, and D. pseudoobscura Poxn all drove GFP expression that closely matched the pattern and timing of the D. melanogaster reporter construct (Figure 2H–I; Figure S3G′–I′). The ability of the posterior lobe enhancer region to produce strong expression in the developing posterior lobe, despite the lack of this structure in these species strongly indicated that it predated the evolution of this novelty.

As our findings implied the absence of functionally significant changes in the Poxn enhancer during the evolution of the posterior lobe, we next tested whether a non-lobed species’ enhancer could rescue the posterior lobe of a D. melanogaster Poxn mutant. The D. melanogaster posterior lobe enhancer is capable of generating a mild rescue of the Poxn null posterior lobe phenotype when fused to Gal4, driving a UAS-Poxn construct (Figure S3L). We observe that the orthologous regulatory region of D. pseudoobscura is also capable of generating a similar degree of rescue (Figure S3M). These experiments confirm the ancestral capability of the posterior lobe enhancer region to drive the expression necessary to generate a derived structure, suggesting that an ancestral function of this region was co-opted during the evolution of this novelty. We subsequently considered what this ancestral activity may be.

In the initial screen of the Poxn regulatory region (Boll and Noll, 2002), several additional activities of Poxn were mapped to a domain overlapping the posterior lobe activity (Figure 2A). As these specificities may represent ancestral functions that were co-opted as the posterior lobe originated, we examined whether any of these were contained within our reporter fragment. Although many of the described activities were located outside of our reporter construct, strong expression was observed in an embryonic structure, the posterior spiracle (Figure 3A). Indeed, further subdivision of our reporter fragment failed to separate posterior spiracle from posterior lobe activities (Figure S3A). We next evaluated the possibility that the posterior spiracle enhancer of Poxn was coopted during the origination of the posterior lobe.

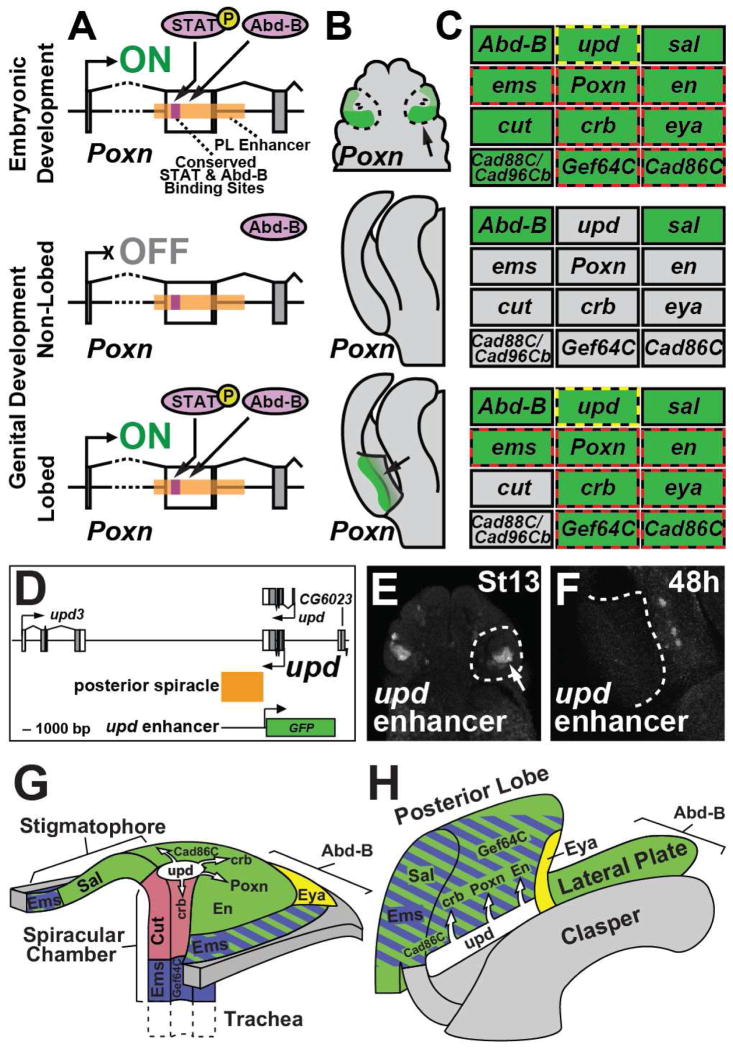

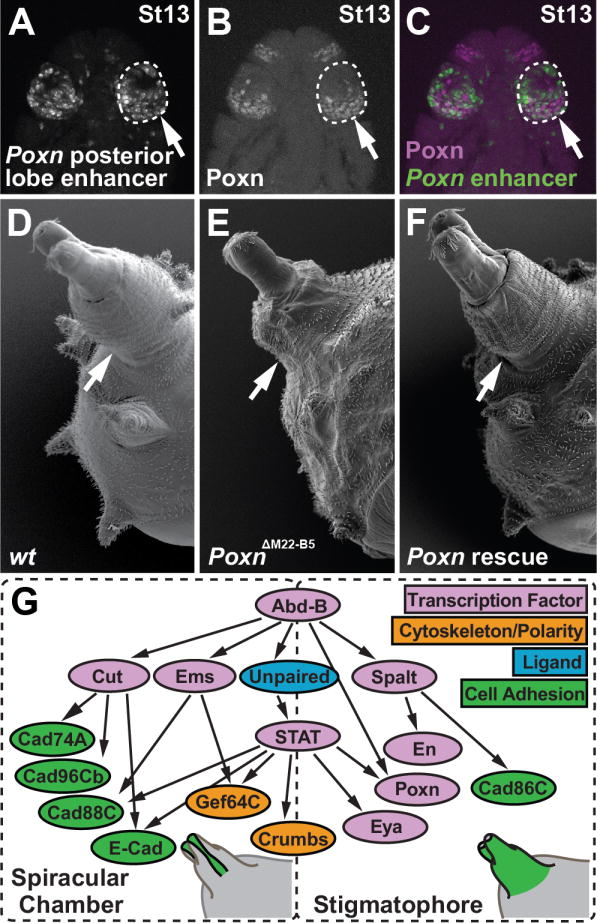

Figure 3.

The posterior lobe enhancer of Poxn is active in the Hox-regulated network of the posterior spiracle. (A) Transgenic embryo bearing the D. melanogaster posterior lobe enhancer reporter. (B) Antibody staining of Poxn protein in the posterior spiracle anlagen of the stage 13 (St13) D. melanogaster embryo presented in panel A. (C) Merged image of panels A and B, showing the Poxn enhancer (green) and Poxn protein (magenta). (D) Scanning electron micrograph of a wild-type third instar larva, showing the posterior spiracle structure. (E) The Poxn null mutant posterior spiracle is shorter relative to wildtype. (F) Rescue of posterior spiracle defects of a Poxn mutant by a fragment of the Poxn locus containing the lobe/spiracle enhancer fused to a Poxn cDNA. (G) Diagram of the posterior spiracle network, adapted from (Hu and Castelli-Gair, 1999; Lovegrove et al., 2006). The addition and placement of Poxn and eya within this network is based upon data presented in this work. Arrows in A–F point to the posterior spiracle. See also Figure S3.

Shared topology and membership of the posterior lobe and spiracle networks

The posterior spiracle is a larval structure that is connected to the tracheal system, providing gas exchange to the larva (Figure 3D). Poxn is expressed in the embryonic region that develops into the posterior spiracle (Figure 3B), and Poxn mutants exhibit multiple defects in the spiracle, including transformation of sensory structures (Boll and Noll, 2002), and a shortening of the stigmatophore, an external protuberance that supports the spiracle (Figure 3E). The stigmatophore defect of Poxn can be rescued by a transgenic construct containing the posterior lobe and spiracle enhancer fused to a Poxn cDNA (Figure 3F). The posterior spiracle is specified during embryogenesis by a network of genes that is activated by the Hox gene Abdominal-B (Abd-B) (Figure 3G) (Hu and Castelli-Gair, 1999). Intriguingly, genital development also depends upon Abd-B, resulting in genital-to-leg transformations in its absence (Estrada and Sánchez-Herrero, 2001).

Considering the apparent parallels between the posterior lobe and the posterior spiracle, we speculated that additional components of the spiracle network might be active in the developing genitalia. The JAK/STAT pathway plays a critical role in the posterior spiracle network (Lovegrove et al., 2006), and its ligand, encoded by the unpaired gene (upd, also known as os) (Harrison et al., 1998), is expressed at high levels in the developing posterior lobe (Figure 4A). This pattern is consistent with the activity of a JAK/STAT signaling reporter (Bach et al., 2007), which is expressed at high levels during posterior lobe development (Figure 4B, Figure S4D–F). Reduction of JAK/STAT signaling in the genitalia by transgenic RNAi hairpins directed towards the receptor (dome), kinase (hop) or transcription factor (Stat92E) resulted in drastic reductions in the posterior lobe’s size compared to a control RNAi hairpin (Figure 4C–F, 4T). Hence, the major signaling pathway that patterns the posterior spiracle is also active in the novel posterior lobe structure.

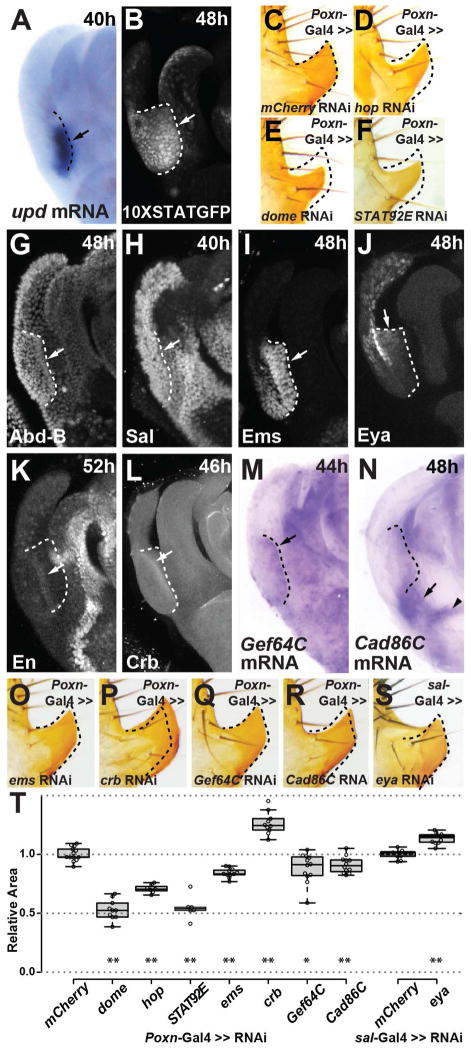

Figure 4.

Shared topology and membership of the posterior lobe and spiracle networks. Antibody staining (G–L) and in situ hybridization (A, M, N) reveal the deployment of several posterior spiracle network genes within the posterior lobe during genital development (arrows). (A–B) Expression of upd mRNA in the developing lobe (A) closely mirrors the activity of a 10XStat92E-GFP reporter (B). (C–F) Reduction in expression of members of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway hop (D), dome (E) or Stat92E (F) reduces the size of posterior lobe relative to a control (C). (G–I) The top-tier spiracle network factor Ems (I) is strongly expressed within the developing posterior lobe, while Abd-B (G) and Sal (H) are present more generally throughout the lateral plate from which the lobe emerges. (J–N) Downstream spiracle network factors Eya (J) and En (K), as well as terminal differentiation factors Crb (L), Gef64C (M), and Cad86C (N) are all expressed at specific regions and stages of posterior lobe development. (O–S) Transgenic RNAi hairpin mediated reduction in expression of spiracle network members ems (O), crb (P), Gef64C (Q), Cad86C (R), or eya (S) alters the size of posterior lobe compared to a control (shown in C). (T) Box plot depicting the relative area of posterior lobes subject to RNAi treatments, and normalized to a control. Asterisks denote significant differences (student’s paired t-test, *p <.05, ** p <.005). Dashed lines mark the position of the developing posterior lobe. (A, B, G–N) or demonstrate altered posterior lobe shape (D–F, O–S) compared to a control (C). Arrowhead in (N) identifies a pattern that is not unique to lobed species (Figure S6E). See also Figures S4 and S5.

We identified three additional top-level transcription factors of the posterior spiracle network that are active during the development of the posterior lobe. Abd-B and Spalt proteins are both deployed in broad domains that include the posterior lobe (Figure 4G–H; Figure S4I–J), consistent with severe genital defects in Abd-B (Estrada and Sánchez-Herrero, 2001; Foronda et al., 2006) and spalt mutants (Dong et al., 2003). In contrast, Empty spiracles (Ems), named for its spiracle phenotype (Jürgens et al., 1984), is expressed in a restricted genital pattern similar to Poxn (Figure 4I; Figure S4K). In summary, five transcription factors required for posterior spiracle development (Abd-B, Poxn, Spalt, Ems, and activated STAT) are deployed in the novel posterior lobe context, suggesting a highly similar trans regulatory landscape governing these two structures.

While the trans regulatory landscapes of the lobe and spiracle bear an unexpected resemblance, they also appear to impart a high degree of spatial specificity. Abd-B is restricted to posterior body segments (Celniker et al., 1989), while Poxn, Spalt, and Ems rarely overlap in expression (Dalton et al., 1989; Dambly-Chaudiere et al., 1992; Kühnlein et al., 1994). The JAK/STAT pathway is recurrently deployed during development, but very few tissue settings would include all five factors. We therefore reasoned that downstream genes in the spiracle network might be activated in the developing posterior lobe. To test this possibility, we monitored their expression during genital development. In five genes of this network: engrailed (en), crumbs (crb), Gef64C, Cad86C, and eyes absent (eya), we found corresponding expression within the developing posterior lobe (Figure 4J–N; Figure S5A–E). Hence, a total of at least ten genes are shared between the two networks. We investigated the hierarchal relationship between several of the identified genes by targeting both upper and lower tiers of the network using RNAi hairpins, and measuring downstream effects on gene expression. Reduction of JAK/STAT signaling led to measurable decreases in the expression of Ems, Crb, and Eya (Figure S5F–K), while the reduction of crb, Gef64C, or Cad86C did not alter the pattern of Ems expression or JAK/STAT pathway activity measured from the 10X STAT reporter (not shown). Two genes whose expression in the posterior lobe depends on dome have been linked to JAK/STAT activity in the posterior spiracle, crb (Lovegrove et al., 2006) and eya (see below). These results support a shared topology between the two networks.

The sharing of genes between the spiracle and lobe networks may be due to their recent recruitment to posterior lobe development, which would predict that their expression is specific to species that possess this structure. To determine whether the activity of these genes differs between lobed and non-lobed species, we examined their expression in non-lobed species at timepoints corresponding to stages in which the D. melanogaster lobe emerges. Ems exhibits strong lobe-specific activity that is absent in non-lobed species (Figure S4K), however both Spalt and Abd-B are widely and strongly expressed in all species tested (Figure S4I–J). upd mRNA is weakly present in early genitalia prior to lobe development in both lobed and non-lobed species, but persists and intensifies in D. melanogaster during lobe development (Figure S4A). Downstream spiracle network genes eya, en, crb, Gef64C and Cad86C are active in several locations within the genitalia, but all exhibit unique lobe-specific expression patterns (Figure S5A–E). Thus, of the ten shared genes that we have discovered, eight are unique to lobed species during the stages of this structure’s emergence.

To confirm that the identified posterior spiracle genes actively participate in posterior lobe development, we targeted ems, crb, Gef64C, Cad86C, and eya with RNAi hairpins driven by genital drivers. Reduction of ems, Gef64C and Cad86C significantly reduced the size of the posterior lobe suggesting that they positively contribute to lobe development, while reduction of crb and eya significantly increased the size of the lobe compared to a control RNAi hairpin, which may indicate an inhibitory or restrictive role in the lobe’s development or expansion (Figure 4O–T). Thus, genes of the spiracle network that are specifically restricted to this novel structure during its development contribute to its construction.

Shared enhancers underlie the parallel topologies of the lobe and spiracle networks

The striking similarity between the posterior lobe and spiracle networks may reflect the convergent evolution of similar network topologies, or could result from co-option of the ancestral posterior spiracle network in generating the lobe. To distinguish between co-option and coincidence, we tested additional enhancers of the posterior spiracle network for posterior lobe activity (see Experimental Procedures). In the case of co-option, multiple enhancers of the posterior spiracle network would be active in the posterior lobe, whereas convergence would produce enhancer activities in distinct locations within each shared gene’s regulatory region.

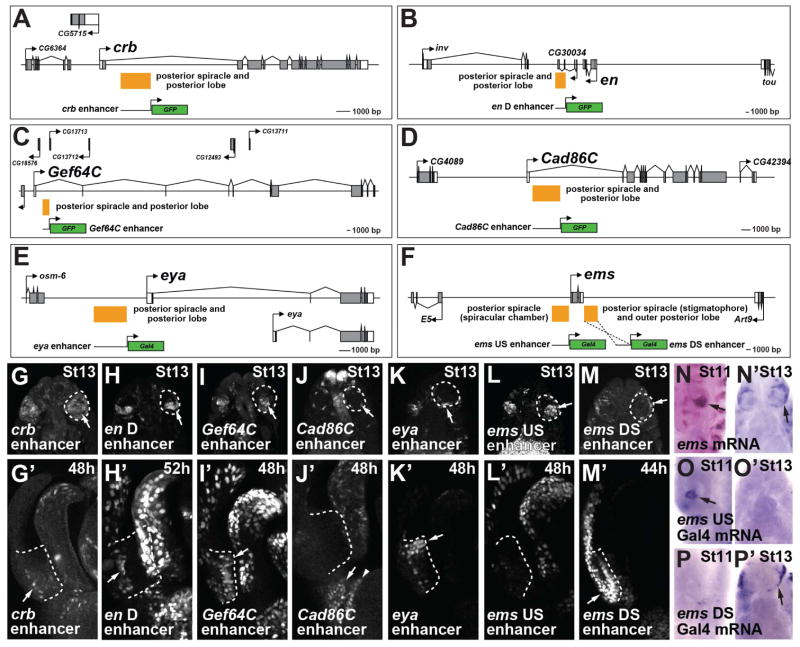

The crb gene is deployed in the posterior spiracle through an intronic JAK/STAT responsive enhancer (Lovegrove et al., 2006), which we found to be active in the posterior lobe (Figure 5A, 5G, and 5G′). A recent screen of the regulatory regions of invected (inv) and en identified a posterior spiracle enhancer (Cheng et al., 2014), which consistently drives weak expression during late posterior lobe development (Figure 5B, 5H and H′). We discovered a region of the Gef64C gene that is active in both the posterior spiracle and posterior lobe patterns (Figure 5C, 5I, and 5I′). We also discovered a region of the Cad86C gene that consistently recapitulates a portion of its posterior spiracle expression domain, as well as a lobe-associated pattern that is specific to lobed species (Figure 5D, 5J and 5J′, white arrow). For eya, a new member of the posterior spiracle network identified in this study, we localized an upstream enhancer that recapitulates its genital expression pattern (Figure 5E and 5K′). This enhancer is also active in the outer edge of the larval spiracle’s stigmatophore (Figure 5K). While a previously identified posterior spiracle enhancer upstream of ems (Jones and McGinnis, 1993, Figure 5L) lacked activity in the posterior lobe (Figure 5L′), we identified an additional enhancer located just downstream of the transcription unit that is activated in both settings (Figure 5F, 5M, and 5M′). This downstream (DS) enhancer of ems recapitulates a previously undescribed activity in the outer edge of the stigmatophore (Figure 5N′ and 5P′) but is not active in the initial spiracular chamber pattern (Figure 5P). In conclusion, we have identified seven enhancers (Poxn, crumbs, en, Gef64C, Cad86C, eya, and ems) of the posterior lobe network that can be traced to overlapping functions in the posterior spiracle. Given the large size of their respective regulatory regions, we postulated that the coincidence of lobe and spiracle enhancers would be highly unlikely due to chance alone. Simulations in which we randomized the locations of lobe and spiracle reporter fragments across the full extent of each of the seven loci confirmed an extremely low probability that the observed lobe and spiracle enhancer fragments would overlap by a single nucleotide (p = 6 × 10−8).

Figure 5.

Co-option of posterior spiracle enhancers to posterior lobe development. (A–F) Schematic diagrams of genomic loci in which an enhancer activated in both the posterior lobe and posterior spiracle were localized (orange boxes). Reporter constructs contain the schematized segment fused to either GFP or Gal4. (G-M,G′-M′) GFP reporter expression driven in transgenic D. melanogaster by enhancers for crb (G, G′), en (H, H′), Gef64C (I, I′), Cad86C (J, J′), eya(K, K′), ems US enhancer (L, L′) and ems DS enhancer (M, M′) in the posterior spiracle (G–M), and in the posterior lobe (G′-M′). (N–P) ems mRNA is first present at stage 11 in cells that contribute to the spiracular chamber, a pattern recapitulated by the ems US reporter (O), but not by the ems DS reporter (P). (N′-P′) ems is also active later during posterior spiracle development around the border of the stigmatophore (arrow) and in each embryonic segment, a pattern not encoded in the upstream enhancer (O′), but is recapitulated by the ems DS reporter (P′, arrow). (L′) The ems US reporter is not expressed within the developing posterior lobe. (J′) In addition to a lobe specific pattern (arrow), the Cad86C reporter also recapitulates a conserved pattern at the edge of the anal plate (arrowhead).

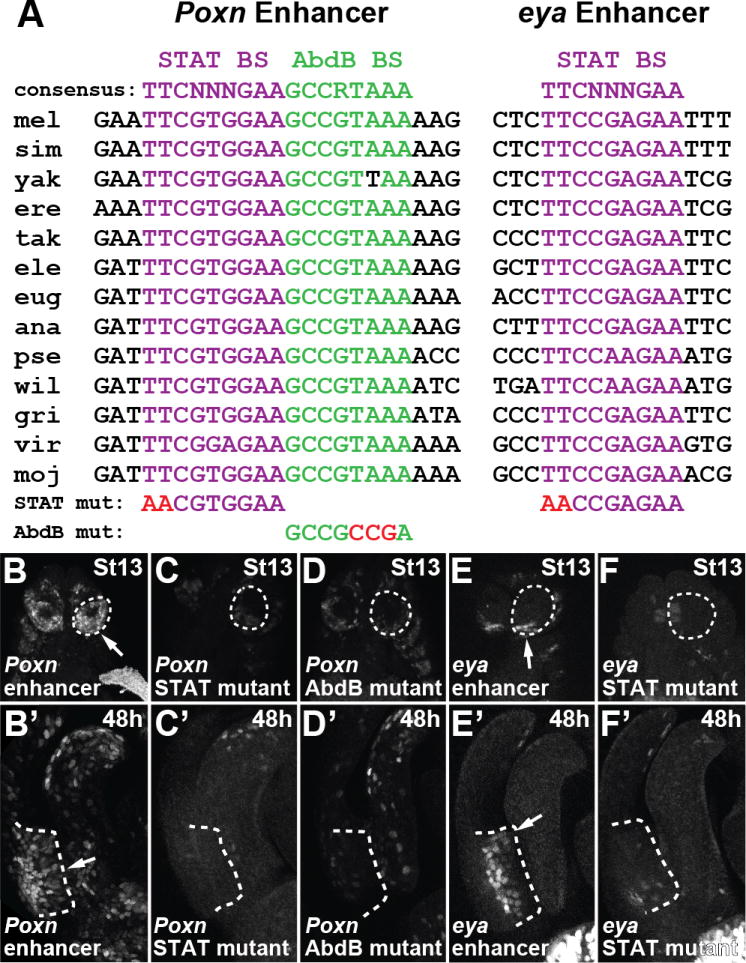

The activation of enhancers in both new and old contexts depends on direct input from Hox and signaling pathway factors

A hallmark of co-option of regulatory sequences is the use of individual transcription factor binding sites in two or more developmental contexts (Rebeiz et al., 2011). The similarities in lobe and spiracle network topologies and enhancer locations strongly suggested that transcription factor binding sites within posterior spiracle enhancers would be required for posterior lobe function. Therefore, we searched for conserved transcription factor binding sites that could mediate functions common to both networks. Within the Poxn posterior lobe enhancer, we identified instances of high quality binding sites for STAT and Abd-B, both of which were contained within an 897 bp fragment active in both contexts (Figure S3A). In addition, we identified a high quality binding site for STAT within a 294 bp interval defined by two overlapping reporters of the eya enhancer that were active in both locations (Figure S6C and S6D). Comparisons to other sequenced Drosophila species revealed that these three sites are highly conserved (Figure 6A), consistent with their potential function in the deeply conserved posterior spiracle structure. Introduction of a 2-bp mutation that is known to disrupt STAT binding (Lovegrove et al., 2006) drastically reduced activity of the Poxn reporter in both the posterior lobe and posterior spiracle (Figure 6B–C and 6B′–C′), and similarly eliminated activity of the eya enhancer reporter in both setttings (Figure 6E–F and 6E′-F′). Introduction of a 3-bp mutation that disrupts Abd-B binding (Williams et al., 2008) extinguished Poxn enhancer activity in the posterior lobe and significantly reduced posterior spiracle expression by 57% (Figure 6D and 6D′). These results demonstrate the co-option of enhancers into a novel setting through the redeployment of pre-existing transcription factor binding sites.

Figure 6.

Redeployment of Poxn and eya in the posterior lobe required ancestral binding sites for Abd-B and STAT that function in the posterior spiracle context. (A) Alignment of a Stat92E binding site (purple text) and an Abd-B binding site (green text) of the Poxn lobe/spiracle enhancer and a Stat92E binding site (purple text) of the eya lobe/spiracle enhancer, showing near perfect conservation among sequenced Drosophila species. (B–D, B′-D′) Mutations to two bases in a STAT binding site (C, C′), or three bases in an Abd-B binding site (D, D′) reduces both posterior spiracle (C–D) and posterior lobe (C′-D′) activity compared to the wildtype Poxn enhancer (B, B′). Mutation of two bases in a STAT binding site (F, F′) reduces both posterior spiracle (F) and posterior lobe (F′) activity compared to the wildtype eya enhancer (E, E′). See also Figure S6.

DISCUSSION

Here, we have shown how a gene regulatory network underlying a novel structure, the posterior lobe, is composed of components that are active in the embryonic posterior spiracle, an ancestral Hox-regulated structure that was present at the inception of this novelty (Fig. 7). These findings confirm previous speculation that network co-option proceeds through the re-use of individual transcription factor binding sites within enhancer sequences (Gao and Davidson, 2008; Monteiro and Podlaha, 2009). Further, our data help calibrate expectations concerning the degree of physical similarity between novel and ancestral structures during co-option events. Below, we briefly discuss how the architecture of the posterior spiracle network may have predisposed it for co-option in the genitalia, and explore the general implications of our findings with regard to the origins of morphological novelty.

Figure 7.

Model depicting the co-option of genes, enhancers, and transcription factor binding sites during the origination of the novel posterior lobe. (A) (top) The posterior spiracle enhancer of Poxn binds Abd-B and phosphorylated STAT in the embryonic posterior spiracle anlagen to activate expression (“ON”). (middle) In species lacking a posterior lobe, the enhancer is not activated during genital development (“OFF”). (bottom) The deployment of regulatory factors of the spiracle network during late stages of genital development in lobed species resulted in the activation of the Poxn spiracle enhancer by Abd-B and activated STAT. (B–C) Summary of Poxn expression (B) and the status of the posterior spiracle network (C) in the three developmental contexts. (C) Expressed genes are shaded in green, while inactive genes are shaded grey. Genes activated by a shared lobe/spiracle enhancer are outlined with red dashes. The yellow dashes surrounding the upd node indicates its activation in the spiracle through an enhancer that lacks lobe activity. (D) Schematic diagram of the upd locus in which a posterior spiracle enhancer was identified (orange box). (E–F) Reporter construct containing the schematized segment fused to a GFP reporter is active in the posterior spiracle (E), but not in the posterior lobe (F). (G–H) Illustrated three-dimensional models of the developing posterior spiracle at embryonic stage 13 (G) and the developing posterior lobe (H). Important structural domains for both tissues are identified. The Hox gene Abd-B is expressed in all depicted genital structures and is deployed throughout the entire body segment containing the posterior spiracle. Zones of expression for top-tier factors Spalt (green) Ems (blue) and Cut (red) are shown. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway ligand Unpaired is shown in white, with arrows pointing toward tissues in which the JAK/STAT signaling response has been demonstrated. Downstream network genes Eya (yellow), Poxn, Engrailed, Crumbs, Gef64C and Cad86C are deployed in distinct portions of both tissues. See also Figure S7.

While our results illustrate the downstream consequences of co-option, the upstream causative events await characterization. We suspect that some number of high-level regulators of the posterior spiracle network recently evolved novel genital expression patterns through alterations within their regulatory regions. Currently, Unpaired represents the best candidate upstream factor, as it is positioned near the top of the spiracle network, differs in expression greatly between lobed and non-lobed species (unlike Spalt and Abd-B), and is the only high-level factor in the spiracle network for which a shared lobe/spiracle enhancer has yet to be identified (Figure 7C). Indeed, a reporter screen of the 30kb of regulatory DNA immediately surrounding the upd gene identified a posterior spiracle enhancer that is not deployed in the posterior lobe, marking an important point of divergence separating the posterior spiracle and posterior lobe networks (Figure 7D–F). However, the identification of enhancers controlling upd expression in the posterior lobe will be required to resolve its role in this structure’s origination.

The architecture of the posterior spiracle network may have shaped the possible developmental contexts in which it could be co-opted. The Hox factor Abd-B has a deeply conserved role in the insect abdomen and genitalia (Kelsh et al., 1993; Yoder and Carroll, 2006). The top-level factors of the posterior spiracle network depend upon Abd-B for activation in the embryo (Figure 3G) (Hu and Castelli-Gair, 1999). This regulation by Abd-B extends to lower tiers of the network, such as Poxn (Figure 6A, 6D and 6D’, Table S1). The tight integration of Abd-B with multiple tiers of the posterior spiracle network may have limited this network’s re-deployment to posterior body segments that express Abd-B. Indeed, several components of this network (Poxn, ems, upd) are activated early during genital development in the presumptive cleavage furrow separating the lateral plate from the clasper (Figures 2B, S4K, and S4A). This may represent the aftereffect of multiple waves of re-deployment in Abd-B expressing tissues. Examination of additional examples of network co-option at the level of constituent regulatory sequences could reveal general rules that govern and bias network redeployment.

Historically, the identification of co-option events has relied upon comparative analyses of gene co-expression. The first examples of co-option were diagnosed by finding novel gene expression patterns near zones of ancestral function, such as the deployment of the posterior wing patterning circuit within novel butterfly eyespots (Keys, 1999). Subsequently, many examples of co-option have involved educated guesses of the types of networks that contribute to the novelty, such as the role of the appendage specification network within beetle horns (Moczek and Nagy, 2005; Moczek et al., 2006), or the sharing of the biomineralization network between adult and larval skeletons of sea urchins (Gao and Davidson, 2008). Our data suggest that tracing the evolutionary origins of individual enhancers provides a less biased path for connecting novelties to their ancestral beginnings, as any of the seven enhancers we have characterized in the posterior lobe would have led us to the spiracle network. Further, this approach is likely to illuminate the underlying cellular mechanisms by which the co-option of a network is translated into a novel developmental outcome.

Rather than generating a serial homolog of the posterior spiracle, the co-option event forming the posterior lobe resulted in an epithelial outgrowth, likely owing to the deployment of only a portion of the spiracle network in the genitalia. This is reflected by the absence of the Cut transcription factor and downstream genes (Figure S7B–L) that control the spiracular chamber’s development (Hu and Castelli-Gair, 1999). Of the ten genes we have identified in both networks, nine are active in the stigmatophore (Figure 7G–H), the outer sheath of the posterior spiracle that protrudes from the body through a process that involves convergent extension (Brown and Castelli-Gair Hombría, 2000; Hu and Castelli-Gair, 1999). Collectively, these findings imply that similar morphogenic processes are activated by this shared network in the novel setting of the posterior lobe. We propose that the inspection of enhancers underlying other novel three-dimensional structures may reveal similar networks that have been used over and over again to generate “unique styles of architecture” within developing tissues (Zuckerkandl, 1976).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Fly strains and husbandry

All flies were reared on a standard cornmeal medium. Species used in this study were obtained from the UC San Diego Drosophila Stock Center (Drosophila biarmipes #0000-1028.01, Drosophila ananassae #0000-1005.01, Drosophila simulans #14021-0251.165, Drosophila pseudoobscura #0000-1006.01, Drosophila sechellia #14021-0248.03, Drosophila erecta #14021-0224.01, Drosophila yakuba # 14021-0261.00). The Drosophila melanogaster line used in this study is mutant for yellow and white (y1w1, Bloomington Stock Center #1495), and was isogenized for 8 generations.

Pupal Genital Sample Preparation

To collect developmentally staged genital samples, white prepupae were sorted by sex, and incubated at 25°C for 24 hours to 48 hours. Pupae were cut in half in cold PBS, extricated from the pupal case, and flushed with cold PBS to remove fat bodies and internal organs while preserving the developing genital epithelium. Carcasses were then fixed in PBS with 0.1% Triton-X and 4% paraformadehyde (PBT-fix) at room temperature for 30 minutes. Samples containing fluorescent reporters were washed three times for 10 minutes in PBS with 0.1% Triton-X (PBT) then imaged immediately. Samples to be used for in situ hybridization were rinsed twice in methanol and stored in ethanol at −20°C.

Embryo Collection

Embryos were collected from grape agar plates (Genesee Scientific) in egg-lay chambers that were incubated at 25°C for up to 20 hours. Embryos were dechorionated in 50% bleach for 3 minutes, washed in distilled water, and collected on a nitrile filter. Embryos were then fixed for 20 minutes in scintillation vials containing PBS, 2% paraformaldehyde, and 50% heptane. The PBS layer was removed from the vial and replaced with an equal amount of methanol. Samples to be used for in situ hybridization were vortexed for 30 seconds, removed from the methanol layer, rinsed twice in methanol then stored in ethanol. Samples containing fluorescent reporters or to be used for immunostaining were shaken vigorously by hand for 1 minute, rinsed in methanol once then quickly rinsed in PBT three times to prevent the degradation of GFP and antibody epitopes.

Immunostaining

Embryo and genital samples were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted in PBT. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit-anti-Poxn 1:100 (Dambly-Chaudiere et al., 1992), rabbit anti-Ems 1:200 (Dalton et al., 1989), rabbit anti-Spalt 1:500 (Barrio et al., 1996), mouse anti-Eya 1:100 (Bonini et al., 1997), mouse anti-Crb 1:50 (Tepass and Knust, 1993), mouse anti-Engrailed/Invected 1:500 (Patel et al., 1989), rat anti-E-cadherin 1:100 (antibody DCAD2, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), and mouse anti-Cut 1:100 (antibody 2B10, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). After several washes with PBT to remove unbound primary antibody, samples were incubated overnight in diluted secondary antibody (donkey anti-mouse Alexa 488, and donkey anti-rabbit Alexa 647, both at 1:400 dilution from Molecular Probes, or goat anti-rat Alexa 488 at 1:200 dilution from Molecular Probes) to detect bound primary antibody. Samples were washed in PBT to remove unbound secondary antibody, incubated for 10 minutes in 50% PBT and 50% glycerol solution, then mounted on glass slides in an 80% glycerol 0.1M Tris-HCL pH 8.0 solution.

in situ hybridization

in situ hybridization was performed as previously described in (Rebeiz et al., 2009) with the modification that we used an InsituPro VSi robot (Intavis Bioanalytical Instruments). Fixed embryo and genital samples were first dehydrated in a 50% xylenes/50% ethanol solution for 30 minutes at room temperature. Xylenes were removed by several washes with ethanol before the samples were loaded into the InsituPro VSi. During the automated steps, the samples were washed in methanol, rehydrated in PBT, fixed in PBT-fix, incubated in 1:25,000 proteinase K PBT (from a 10mg/mL stock solution), fixed in PBT-fix, and subjected to several washes in hybridization buffer. Samples were probed with digoxygenin riboprobes targeting the coding regions of selected genes (See Supplemental Experimental Procedures, Primers for amplifying species-specific mRNA probes) for 18 hours at 65°C. Unbound riboprobe was removed in several subsequent hybridization buffer washes, and washed several times in PBT. Samples were removed from the robot, and incubated overnight in PBT with 1:6000 anti-digoxygenin antibody Fab fragments conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Roche Diagnostics). Alkaline phosphatase staining was then developed for several hours in NBT/BCIP color development substrate (Promega). Samples were then washed in PBT and mounted on glass slides in an 80% glycerol 0.1M Tris-HCL, pH 8.0 solution.

Transgenic constructs

Enhancer elements were cloned using the primers listed in Supplemental Experimental Procedures, Primers for transgenic constructs, and inserted into the vector pS3aG (GFP reporter) or pS3aG4 (Gal4 reporter) using AscI and SbfI restriction sites as previously described (Williams et al., 2008). Primers were designed and sequence conservation was assessed using the GenePalette software tool (Rebeiz and Posakony, 2004). Targeted regions were cloned from genomic DNA purified using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen). Transcription factor binding site mutations were introduced using overlap extension PCR with mutant primers (See Supplemental Experimental Procedures, Primers for generating mutant binding site reporters by overlap extension PCR). All GFP reporters were inserted into the 51D landing site on the 2nd chromosome (Bischof et al., 2007), or the third chromosome 68A4 “attP2” site (Groth et al., 2004) by Rainbow Transgenics. Gal4 insertions depicted in Figure S3 were inserted into the 68E1 landing site on the third chromosome (Bischof et al., 2007). A full list of transgenes and insertions sites is listed in Supplemental Experimental Procedures, Transgenic lines analyzed.

The Poxn rescue construct depicted in Figure 3F of the main text contains a 7.8kb genomic fragment containing 3kb upstream of the Poxn coding unit, including the Poxn promoter, and the first 3 exons and 2 introns of Poxn (which includes the lobe/spiracle enhancer). The remainder of the Poxn gene was joined to this construct from a Poxn CDNA. This construct (“L2”) is identical to the “L1” construct published by Boll and Noll, but differs by the inclusion of 1.5 kb additional sequence upstream of the promoter (Boll and Noll, 2002).

The following GFP and Gal4 reporters were obtained from existing sources. 10XStat92E-GFP reporter was obtained from Erika Bach (Bach et al., 2007). Poxn-Gal4 (construct #13 from (Boll and Noll, 2002)) and UAS-Poxn was obtained from Werner Boll. armadillo-GFP was obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (#8556). Several enhancer-GAL4 lines from the Rubin collection (Pfeiffer et al., 2008) were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) and are listed in Supplemental Experimental Procedures, Transgenic lines analyzed. Transgenic RNAi lines from the Harvard TRiP project include: dome (#34618), Stat92E (#33637) hop (#32966), crb (#40869), Cad86C (#27295), Gef64C (#31130), ems (#50673), eya (#35725). mCherry (#35785), a gene that is not present in the Drosophila genome was used as a control for RNAi experiments. The salm-Gal4 driver (#25755) was also obtained from the BDSC.

Microscopy

Adult posterior lobe cuticles and stained in situ hybridization samples were imaged on a Leica M205 stereomicroscope with a 1.6× objective with the extended multi-focus function. Samples stained with fluorescent antibodies or containing fluorescent reporters were imaged via confocal microscopy at 20× magnification on an Olympus Fluoview 1000 microscope. SEM images of third instar larvae were obtained as previously described by Higashijima (Higashijima et al., 1992).

For each transgenic construct, 3–5 independent lines inserted into the 51D landing site (Bischof et al., 2007) or 68A4 “attP2” landing site (Groth et al., 2004) were derived. A list of reporters and corresponding landing sites are reported in Supplemental Experimental Procedures, Transgenic lines analyzed. We compared the relative expression of multiple lines in the genitalia to determine the normal reporter activity of each construct. For quantitative measures, relative fluorescence of the Poxn and eya posterior lobe enhancers, and constructs mutant for STAT and Abd-B sites were determined in both the posterior lobe and posterior spiracle contexts. Mounted genital and embryo samples were imaged at 20× magnification under identical, non-saturating settings uniquely optimized for each sample type. Relative expression within the lobe or spiracle was quantified using ImageJ and assessed using a student’s paired t-test.

Simulations of posterior lobe and spiracle enhancer co-occurrence

The lengths of shared enhancers and the length of each regulatory region in which these enhancers were embedded were input into an in-house Perl script, CRE-overlap-sim. This program randomizes the location of two equally sized segments of DNA (the size of each reporter fragment tested) across the length of each gene’s potential regulatory sequence (the distance from the upstream gene to the gene downstream). For each simulation, the script measures whether the two segments overlapped, and counts a successful co-occurrence when all of the input enhancers overlap by the designated number of nucleotides in their respective regulatory regions. A large overlap, which would be expected for co-opted enhancer sequences will reduce the measured probability of co-occurrence. Our simulations specified a 1 nucleotide overlap, which represents the most permissive, and thus most stringent setting possible to detect non-random co-occurrence. 500,000,000 simulations were performed, and the average p-value as presented in the main text was calculated.

Identification of shared and distinct posterior spiracle/posterior lobe enhancers

A combination of comprehensive whole gene surveys and targeted candidate region tests of non-coding regions of genes shared between the two networks was employed to identify co-opted enhancers. In the case of five out of eight of the identified enhancers, multiple constructs, inserted in at least two distinct genomic locations were tested for activity. For the whole gene surveys, with the exception of upd, we used lines from the Rubin GAL4 collection (Jenett et al., 2012; Pfeiffer et al., 2008), in which non-coding sequences are fused to the GAL4 transcription factor, and inserted into the attP2 site on the third chromosome. We supplemented these searches with constructs we generated (see “Transgenic Constructs”) when necessary. Primers used to amplify reporter constructs are presented in Supplemental Experimental Procedures, Primers for transgenic constructs. We detail the search for each of these enhancers below: crb: Lovegrove et al. identified a spiracle enhancer located in the first intron (Lovegrove et al., 2006), for which we cloned an identical segment into our reporter system. Additionally, we screened all intronic sequences using the Rubin-Gal4 collection, in which the construct overlapping the Lovegrove fragment uniquely recapitulated lobe expression. We additionally cloned the upstream region of crb into our GFP reporter system, and this fragment was not active in the posterior lobe.

en

Cheng et al screened the regulatory regions surrounding engrailed and invected (Cheng et al., 2014). The “D” enhancer from the intergenic region between inv and en was shown to specifically recapitulate the posterior spiracle activity of en. We reconstituted this enhancer by designing primers to clone the identical segment into our reporter system. This construct drove strong expression similar to endogenous posterior spiracle en activity as reported by Cheng, and weak but consistent activity within a subset of the posterior lobe, mirroring the levels that appear late during posterior lobe development (Figure S5B).

eya

We screened the upstream region and introns of eya using the Rubin Gal4 collection. This screen identified a single posterior lobe activity just upstream of the transcription unit. We further confirmed the activity of this enhancer fragment by inserting it into our GFP reporter system, which showed activity in the posterior lobe as well. Both the GFP reporter and the Rubin Gal4 constructs were expressed in the posterior spiracle. We further refined the size of this regulatory region by testing overlapping fragments of the D. sechellia eya enhancer. Two fragments that overlap by 294 bp were active in both spiracle and lobe tissues (Figure S6C–D,C′–D′). The smallest fragment tested was 1060 bp.

ems

Rubin Gal4 lines existed for nearly all of the ~67 kb region encompassing the non-coding DNA surrounding ems. To test a portion of the regulatory region upstream of the ems promoter that is not included in the Rubin Gal4 collection, we cloned three additional overlapping regions into our GFP reporter system. We first tested a Rubin Gal4 line that contains the previously identified upstream enhancer for the spiracular chamber (Jones and McGinnis, 1993) (Figure 5F). This line faithfully reproduced spiracular chamber expression (Figure 5L and 5O), but was not active in the ems posterior lobe pattern (Figure 5L′). Screening the other Rubin collection lines of ems for genital activity, we identified a fragment just downstream of the transcription unit that drove expression partially recapitulating the lobe expression of ems. To determine if this enhancer was indeed distinct from the posterior spiracle activity, we examined its expression in stage 13 embryos, and noticed that it was active in the outer stigmatophore (Figure 5M and 5P′), a pattern that recapitulates endogenous ems expression (Figure 5N′). We cloned a subfragment of this downstream enhancer into our GFP reporter system, confirming the activity of this segment in the posterior lobe and spiracle. In addition, we cloned the orthologous segment of DNA from D. ananassae into our reporter system, demonstrating that a non-lobed species version of ems DS is capable of driving expression within the posterior lobe (Figure S6B′).

Gef64C

A survey of the non-coding region of Gef64C identified a segment containing several binding sites for genes in the spiracle network, including a high affinity binding site for Abd-B (Ekker et al., 1994), and two candidate STAT binding sites, all of which were conserved to D. pseudoobscura. Fusing this segment of DNA into our reporter system revealed expression in the spiracular chamber of the posterior spiracle, embryonic hindgut, and in several zones in the developing genitalia that recapitulate its endogenous expression (clasper, lobe, anal plate, and hypandrium, Figure 4M). Further truncation of this segment of DNA separated the posterior spiracle and posterior lobe patterns from the other activities, localizing this enhancer to the first intron. This truncation includes the two candidate STAT binding sites but not the candidate Abd-B binding site (Table S1).

Cad86C

A screen of the non-coding regions surrounding Cad86C identified an intronic region near the promoter that included a Spalt site (Barrio et al., 1996) which is conserved to D. ananassae (Table S1). We cloned a 3003 bp segment of DNA that included this region into our reporter system. This reporter consistently recapitulated a portion of the endogenous Cad86C activity in the posterior spiracle and embryonic anus (Figure 5J and Figure S5E), and drove expression in the anal plate pattern common to both lobed and non-lobed species (Figure 5J′ arrowhead and Figure S5E), as well as the lobe-specific pattern just posterior to the lobe (Figure 5J′ arrow and Figure S5E).

upd

We screened the 30kb intergenic non-coding DNA between upd (also os) and its neighboring genes upd3 and CG6023 by cloning eight overlapping segments into our reporter system. One reporter directly downstream of upd drove expression within the posterior spiracle (Figure 7E), matching the endogenous upd pattern (Figure S4G), and none of the tested reporters drove expression within the posterior lobe. The region that drove posterior spiracle expression contains a high quality match to the Abd-B binding site (Ekker et al., 1994), which is conserved to at least D. virilis.

Identification of predicted conserved transcription factor binding sites in minimal shared enhancers

Using the GenePalette Software tool (Rebeiz and Posakony, 2004), we compared the orthologous regions of the shared posterior spiracle and posterior lobe enhancers from D. melanogaster, D. simulans, D. yakuba, D. biarmipes, D. ananassae, D. pseudoobscura, and D. virilis. We screened for predicted binding sites for STAT (Yan et al., 1996), Spalt (Barrio et al., 1996) and for a high-fidelity binding site for Abd-B (Ekker et al., 1994). Putative conserved transcription factor binding sites are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Newly evolved Drosophila adult genital structure allows analysis of network history

The adult structure evolved by co-opting the network of a larval breathing structure

Ten genes, including seven transcription factors, are shared between both networks

Seven embryonic regulatory sequences are re-deployed during genital development

Acknowledgments

The authors thank J.N. Pruitt, T.M. Williams, J. Posakony, and members of the Rebeiz laboratory for thoughtful discussions and comments on the manuscript. We thank W. McGinnis, R. Barrio, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for generously providing antibodies used in this study. Drosophila strains were provided by the UCSD Drosophila species stock center, the Harvard TRiP, and the Bloomington Drosophila stock center. E. Bach, B. Gyeong-Hun, G. Campbell, and A. Kopp provided Drosophila stocks. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM107387 to M.R.) and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (to M.R.). N.R.D. was supported by an HHMI grant to the University of Pittsburgh.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: M.R. and W.J.G. designed the study, performed experiments, and wrote the paper. W.C.J. cloned constructs and established transgenic lines, Y.L. and N.R.D. screened and characterized the eya enhancer. S.J.S screened the upd locus. W.B. and M.N. performed analyses of Poxn expression and mutant phenotypes in the posterior spiracle. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abouheif E. Establishing homology criteria for regulatory gene networks: prospects and challenges. Novartis Found Symp. 1999;222:207–221. doi: 10.1002/9780470515655.ch14. discussion 222–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach EA, Ekas LA, Ayala-Camargo A, Flaherty MS, Lee H, Perrimon N, Baeg GH. GFP reporters detect the activation of the Drosophila JAK/STAT pathway in vivo. Gene Expr Patterns. 2007;7:323–331. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrio R, Shea MJ, Carulli J, Lipkow K, Gaul U, Frommer G, Schuh R, Jäckle H, Kafatos FC. The spalt-related gene of Drosophila melanogaster is a member of an ancient gene family, defined by the adjacent, region-specific homeotic gene spalt. Dev Genes Evol. 1996;206:315–325. doi: 10.1007/s004270050058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof J, Maeda RK, Hediger M, Karch F, Basler K. An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line-specific phiC31 integrases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3312–3317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611511104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boll W, Noll M. The Drosophila Pox neuro gene: control of male courtship behavior and fertility as revealed by a complete dissection of all enhancers. Development. 2002;129:5667–5681. doi: 10.1242/dev.00157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonini NM, Bui QT, Gray-Board GL, Warrick JM. The Drosophila eyes absent gene directs ectopic eye formation in a pathway conserved between flies and vertebrates. Development. 1997;124:4819–4826. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.23.4819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner JT. The origins of multicellularity. Integr Biol Issues, News, Rev. 1998;1:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Castelli-Gair Hombría J. Drosophila grain encodes a GATA transcription factor required for cell rearrangement during morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127:4867–4876. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.22.4867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celniker SE, Keelan DJ, Lewis EB. The molecular genetics of the bithorax complex of Drosophila: characterization of the products of the Abdominal-B domain. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1424–1436. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.9.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Brunner AL, Kremer S, DeVido SK, Stefaniuk CM, Kassis JA. Co-regulation of invected and engrailed by a complex array of regulatory sequences in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 2014;395:131–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne J. The genetics of an isolating mechanism between two sibling species of Drosophila. Evolution (N Y) 1993;47:778–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick FH. The origin of the genetic code. J Mol Biol. 1968;38:367–379. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton D, Chadwick R, McGinnis W. Expression and embryonic function of empty spiracles: a Drosophila homeo box gene with two patterning functions on the anterior-posterior axis of the embryo. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1940–1956. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12a.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambly-Chaudiere C, Jamet E, Burri M, Bopp D, Basler K, Hafen E, Dumont N, Spielmann P, Ghysen A, Noll M. The paired box gene pox neuro: a determinant of poly-innervated sense organs in Drosophila. Cell. 1992;69:159–172. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EH. Genomic regulatory systems3: development and evolution. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dong PD, Todi SV, Eberl DF, Boekhoff-Falk G. Drosophila spalt/spalt-related mutants exhibit Townes-Brocks’ syndrome phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10293–10298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1836391100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard WG. Sexual selection and animal genitalia. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ekker SC, Jackson DG, Von Kessler DP, Sun BI, Young KE, Beachy PA. The degree of variation in DNA sequence recognition among four Drosophila homeotic proteins. Eur Mol Biol Organ J. 1994;13:3551–3560. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada B, Sánchez-Herrero E. The Hox gene Abdominal-B antagonizes appendage development in the genital disc of Drosophila. Dev Cambridge Engl. 2001;128:331–339. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foronda D, Estrada B, de Navas L, Sanchez-Herrero E. Requirement of Abdominal-A and Abdominal-B in the developing genitalia of Drosophila breaks the posterior downregulation rule. Development. 2006;133:117–127. doi: 10.1242/dev.02173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F, Davidson EH. Transfer of a large gene regulatory apparatus to a new developmental address in echinoid evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6091–6096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801201105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth AC, Fish M, Nusse R, Calos MP. Construction of transgenic Drosophila by using the site-specific integrase from phage phiC31. Genetics. 2004;166:1775–1782. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.4.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DA, McCoon PE, Binari R, Gilman M, Perrimon N. Drosophila unpaired encodes a secreted protein that activates the JAK signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3252–3263. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashijima S, Michiue T, Emori Y, Saigo K. Subtype determination of Drosophila embryonic external sensory organs by redundant homeo box genes BarH1 and BarH2. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1005–1018. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu N, Castelli-Gair J. Study of the posterior spiracles of Drosophila as a model to understand the genetic and cellular mechanisms controlling morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 1999;214:197–210. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagadeeshan S, Singh RS. A time-sequence functional analysis of mating behaviour and genital coupling in Drosophila: role of cryptic female choice and male sex-drive in the evolution of male genitalia. J Evol Biol. 2006;19:1058–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenett A, Rubin GM, Ngo TTB, Shepherd D, Murphy C, Dionne H, Pfeiffer BD, Cavallaro A, Hall D, Jeter J, et al. A GAL4-driver line resource for Drosophila neurobiology. Cell Rep. 2012;2:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B, McGinnis W. The regulation of empty spiracles by Abdominal-B mediates an abdominal segment identity function. Genes Dev. 1993;7:229–240. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens G, Wieschaus E, Nüsslein-Volhard C, Kluding H. Mutations affecting the pattern of the larval cuticle in Drosophila melanogaster II. Zygotic loci on the third chromosome. Dev Biol. 1984;193:283–295. doi: 10.1007/BF00848157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsh R, Dawson I, Akam M. An analysis of abdominal-B expression in the locust Schistocerca gregaria. Development. 1993;117:293–305. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keys DN. Recruitment of a hedgehog Regulatory Circuit in Butterfly Eyespot Evolution. Science (80- ) 1999;283:532–534. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5401.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keys DN, Lewis DL, Selegue JE, Pearson BJ, Goodrich LV, Johnson RL, Gates J, Scott MP, Carroll SB. Recruitment of a hedgehog regulatory circuit in butterfly eyespot evolution. Science (80- ) 1999;283:532–534. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5401.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp A, True JR. Evolution of male sexual characters in the oriental Drosophila melanogaster species group. Evol Dev. 2002;4:278–291. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2002.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühnlein RP, Frommer G, Friedrich M, Gonzalez-Gaitan M, Weber A, Wagner-Bernholz JF, Gehring WJ, Jäckle H, Schuh R. spalt encodes an evolutionarily conserved zinc finger protein of novel structure which provides homeotic gene function in the head and tail region of the Drosophila embryo. EMBO J. 1994;13:168–179. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuraku S, Usuda R, Kuratani S. Comprehensive survey of carapacial ridge-specific genes in turtle implies co-option of some regulatory genes in carapace evolution. Evol Dev. 2005;7:3–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2005.05002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovegrove B, Simões S, Rivas ML, Sotillos S, Johnson K, Knust E, Jacinto A, Hombría JCG. Coordinated control of cell adhesion, polarity, and cytoskeleton underlies Hox-induced organogenesis in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2206–2216. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moczek AP, Nagy LM. Diverse developmental mechanisms contribute to different levels of diversity in horned beetles. Evol Dev. 2005;7:175–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2005.05020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moczek AP, Rose DJ. Differential recruitment of limb patterning genes during development and diversification of beetle horns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8992–8997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809668106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moczek AP, Rose D, Sewell W, Kesselring BR. Conservation, innovation, and the evolution of horned beetle diversity. Dev Genes Evol. 2006;216:655–665. doi: 10.1007/s00427-006-0087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro A, Podlaha O. Wings, Horns, and Butterfly Eyespots: How Do Complex Traits Evolve? PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller GB, Wagner GP. Novelty in Evolution: Restructuring the Concept. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1991;22:229–256. [Google Scholar]

- Orgel LE. Evolution of the genetic apparatus. J Mol Biol. 1968;38:381–393. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90393-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NH, Martin-Blanco E, Coleman KG, Poole SJ, Ellis MC, Kornberg TB, Goodman CS. Expression of engrailed proteins in arthropods, annelids, and chordates. Cell. 1989;58:955–968. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer BD, Jenett A, Hammonds AS, Ngo TT, Misra S, Murphy C, Scully A, Carlson JW, Wan KH, Laverty TR, et al. Tools for neuroanatomy and neurogenetics in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9715–9720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803697105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebeiz M, Posakony JW. GenePalette: a universal software tool for genome sequence visualization and analysis. Dev Biol. 2004;271:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebeiz M, Pool JE, Kassner VA, Aquadro CF, Carroll SB. Stepwise modification of a modular enhancer underlies adaptation in a Drosophila population. Science (80- ) 2009;326:1663–1667. doi: 10.1126/science.1178357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebeiz M, Jikomes N, Kassner VA, Carroll SB. The evolutionary origin of a novel gene expression pattern through co-option of the latent activities of existing regulatory sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105937108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson HM. Mating Asymmetries and Phylogeny in the Drosophila melanogaster. Pacific Sci. 1988;42:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Sagan L. On the origin of mitosing cells. J Theor Biol. 1967;14:255–274. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(67)90079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small S, Blair A, Levine M. Regulation of even-skipped stripe 2 in the Drosophila embryo. EMBO J. 1992;11:4047–4057. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepass U, Knust E. Crumbs and stardust act in a genetic pathway that controls the organization of epithelia in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1993;159:311–326. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TM, Selegue JE, Werner T, Gompel N, Kopp A, Carroll SB. The regulation and evolution of a genetic switch controlling sexually dimorphic traits in Drosophila. Cell. 2008;134:610–623. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkopp PJ. Genomic sources of regulatory variation in cis and in trans. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:1779–1783. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5064-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan R, Small S, Desplan C, Dearolf CR, Darnell JE. Identification of a Stat Gene That Functions in Drosophila Development. Cell. 1996;84:421–430. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassin A, Orgogozo V. Coevolution between Male and Female Genitalia in the Drosophila melanogaster Species Subgroup. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder JH, Carroll SB. The evolution of abdominal reduction and the recent origin of distinct Abdominal-B transcript classes in Diptera. Evol Dev. 2006;8:241–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2006.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerkandl E. Programs of Gene Action and Progressive Evolution. In: Goodman M, Tashian R, Tashian J, editors. Molecular Anthropology SE - 20. Springer; US: 1976. pp. 387–447. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.