Abstract

CONTEXT

The IUD is extremely effective but infrequently used by young adult women, who disproportionately experience unintended pregnancies. Research has not examined how IUD use may affect sexuality, which could in turn affect method acceptability, continuation and marketing efforts.

METHODS

Focus group discussions and interviews were conducted in 2014 with 50 women between the ages of 18 and 29—either University of Wisconsin students or women from the surrounding community who received public assistance—to explore their thoughts about whether and how IUD use can affect sexual experiences. A modified grounded theory approach was used to identify common themes in terms of both experienced and anticipated sexual acceptability of the IUD.

RESULTS

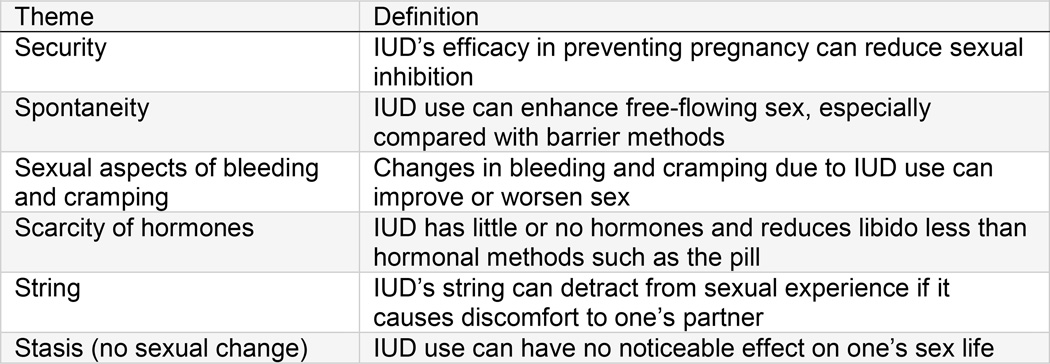

Six themes emerged: Security (IUD’s efficacy can reduce sexual inhibition), spontaneity (IUD can allow for free-flowing sex), sexual aspects of bleeding and cramping (IUD’s side effects can affect sex), scarcity of hormones (IUD has little or no hormones, and reduces libido less than hormonal methods such as the pill), string (IUD’s string can detract from a partner’s sexual experience) and stasis (IUD use can have no impact on sex). Some reported sexual aspects of IUD use were negative, but most were positive and described ever-users’ method satisfaction and never-users’ openness to use the method.

DISCUSSION

Future research and interventions should attend to issues of sexual acceptability: Positive sexual aspects of the IUD could be used promotionally, and counseling about sexual concerns could increase women’s willingness to try the method.

In 2005, Severy and Newcomer argued that sexuality is a “critical” but understudied issue in contraceptive acceptability research.1 Two years later, a commentary in this journal similarly noted a pleasure deficit in the field2: Even though contraceptives are designed for sexual activity, few studies have explored methods’ effects on women’s sexual satisfaction or functioning, let alone how such effects shape contraceptive uptake, adherence and continuation.3 Nonetheless, in recent years, reproductive health researchers have shown increasing interest in how contraception affects women’s sexual well-being and how sexuality may influence contraceptive choices and practices.4–9 This growing body of research suggests significant associations between contraceptives’ sexual acceptability—that is, how they affect users’ sexual experiences—and how consistently and continuously women use them. Given the nascent state of this research, however, substantial gaps in knowledge remain.

One notable gap is the lack of studies on sexual aspects of the IUD—a method that has made a major resurgence in the family planning field in recent years under the banner of long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods, which also include the implant. Given their high efficacy and forgettable nature, as well as their associations with reduction of unintended pregnancy in at least two regions of the United States,10,11 LARC methods are understandably front and center of current family planning programs and policies. Although studies have explored provider- and financial-level barriers to IUD use,12–15 few have employed a patient-centered approach among potential users themselves, especially in terms of how sexuality may shape clients’ satisfaction with their method. To improve the appeal and acceptability of IUDs, research needs to explore how clients’ potential uptake and continued use of IUDs may be associated with sexuality.

A 2014 review identified a small number of LARC studies that included any sexuality measures, and found mixed results and potential methodological limitations, although the IUD was more commonly associated with positive or neutral sexual effects than negative ones.16 None of the studies identified, however, took place in the United States—an inherent limitation, given cultural differences in sexual attitudes and norms. Furthermore, the majority measured sexual acceptability using only one quantitative measure—the Female Sexual Function Index,17 which focuses on physiological functions such as arousal, lubrication and orgasm. Although validated measures of women’s physiological sexual functioning can be very important in research on this topic (and perhaps should be a standard part of contraceptive acceptability studies3), they may miss key domains of overall sexual acceptability, particularly psychological aspects. Qualitative research in particular suggests that women’s sexual preferences for their contraceptive method surpass functioning alone to include partner-based and relational components; inhibition and disinhibition; and personal aesthetic issues relating to touch, feel and other sensations.7,9

To our knowledge, no U.S.-based qualitative study has documented women’s sexual experiences with the IUD. To fill this gap, we collected and analyzed qualitative data on young adult women’s thoughts and experiences regarding the sexual aspects of the IUD. We focused on young adults because, compared with other women, they have a disproportionately high burden of unintended pregnancy and lower rates of LARC method use.18,19

METHODS

Study Design

Data for this analysis derive from a larger qualitative study that took place in Dane County, Wisconsin, a semiurban area of approximately 500,000 inhabitants and home to the University of Wisconsin–Madison; the large majority of county residents are white (81%, compared with 77% nationally), and 13% live below the federal poverty level (compared with 15% nationally).20 We conducted focus group discussions and in-depth interviews to investigate IUD and implant use among 18–29-year-old women; sexuality was one of several barriers and facilitating factors explored. Qualitative research methods such as focus groups and interviews are essential for exploring understudied topics, generating hypotheses and answering questions of why, how and under what circumstances.21 Because research participants generate meanings in their own words, qualitative methods are also good for documenting personal and social meanings, and individual and cultural practices,22 which are all vital to documenting how the IUD relates to sexuality among those who have used the method, as well as those who potentially anticipate IUD use.

To recruit participants, study team members posted and distributed flyers in university buildings, public libraries, Planned Parenthood clinics, university health services, other health clinics (e.g., federally qualified health centers), bus shelters and Job Corps offices. In addition, recruitment e-mails were circulated to university groups; public health departments; representatives of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC); and other pertinent health and social organizations. We also posted information about the study in the community volunteer and “etc.” jobs sections of Craigslist, and in a free local weekly newspaper. Some participants were referred by friends or family members who qualified for the study.

Eligibility criteria included being aged 18–29 and having any history of contraceptive use; in addition, community participants had to be currently receiving at least one form of public assistance (including food stamps, WIC or some form of health insurance, such as an income-based family planning waiver). The second author screened all community respondents by phone and all university respondents by e-mail; she then provided eligible participants with available interview or focus group times and driving or bus directions.

To ensure socioeconomic diversity among participants, we designed a stratified sampling frame: One-third of focus groups and interviews were with current university students, and two-thirds were with women from the community. University students were of interest because of a related project of the investigators, who wish to raise IUD awareness within their local university population.

Data Collection

Focus groups and interviews took place between January and June of 2014; prior to any data collection, the University of Wisconsin–Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board reviewed and waived the study design and instruments. We conducted six focus groups with 40 women who had any history of contraceptive use; of those, eight had used the IUD, and one had used the implant. Focus groups with university participants took place in a campus conference room; focus groups with community participants took place in a conference room of a university-affiliated health clinic located in a bus-accessible, low-income area of Dane County. Focus groups contained 3–10 participants and lasted 1.5–2.5 hours. Twelve interviews took place—all at the second author’s campus office—and lasted 25–55 minutes. The lead author facilitated all focus groups, and the second author conducted all interviews. Two focus group participants also took part in an interview, whereas all other participants took part in either a focus group or an interview.

Focus groups were designed to explore young adult women’s LARC-related knowledge and attitudes, as well as various factors (e.g., medical, relational, sexual) associated with LARC acceptability. We selected focus groups because of their utility in measuring social norms, expectations and values (versus individual beliefs and experiences).22 However, we also wanted to more deeply explore personal experiences of women who had ever used a LARC method. Therefore, we conducted one-on-one interviews with former or current LARC method users.

We developed a lengthy semistructured guide for both focus groups and interviews, with the section on sexuality phrased as follows: “Let’s talk about sex for a moment. So some people notice that certain contraceptives make their sex lives better, some people notice that contraceptives make their sex lives worse, some people notice no effect. What do you think about IUDs?” Focus groups included these probes: “Do you think IUDs have the potential to improve someone’s sex life? Detract from it? Make no difference?” Interviews included this probe: “What are your thoughts on how IUDs have affected your sexual enjoyment, if at all?” We used the same question stem even though we anticipated social-level responses in focus groups and individual-level responses in interviews.

All focus groups and interviews were audio-recorded, and the recordings were transcribed by either a study team member or an independent transcription service. Additionally, after each focus group or interview, the facilitator or interviewer wrote up a 1–2-page memo that summarized the session and highlighted particularly relevant themes or stories. These memos became part of the qualitative data analyzed for the project.

Analysis

Because participants had more familiarity and experience with the IUD than with the implant, we decided to focus our analysis on the sexual aspects of the IUD. Although the majority of focus group participants had not used an IUD, their perceptions on potential sexual aspects of the method are salient in terms of shaping contraceptive clients’ willingness to try these devices. Thus, the remainder of this article distinguishes between experienced and anticipated sexual acceptability of the IUD.

We used an inductive, modified grounded theory approach in analyzing the data—that is, we drew from preexisting themes from the literature and research questions, as well as from themes arising from the data themselves. We had identified a preestablished sexuality code, given our interest in the topic; however, all subthemes arose during analysis on the basis of our review of the memos and data.

About halfway through data collection, the first author generated a coding report of dozens of possible codes on the basis of the research questions of interest (including the sexuality code) and in vivo themes that had arisen; with input from the second and third authors, she winnowed the list down to 20 codes. Trained team members applied codes to relevant blocks of text in each transcript. Two coders independently coded each transcript and then met to discuss the codes. Once 100% agreement was reached, one coder entered all codes from an individual transcript into Atlas.ti. For the current analysis, all team members read over the sexuality coding report, made note of preliminary subthemes, and met to compare and confirm a list of subthemes. Those subthemes became the basis of the results presented below. In refining the subthemes and writing up the results, the lead author referred to memos where appropriate to confirm or augment information about participants.

Once we completed coding and identified subthemes, the first author used descriptive and analytic cross-case analysis23 to document themes with mindfulness toward the following distinct groups: focus group versus interview participants, as well as never-users versus ever-users of an IUD (i.e., women reporting on their IUD experience versus those describing anecdotal or projected sexual acceptability). We present data from ever-users before data from never-users.

We recognize that quotations from focus groups and those from interviews are not fully comparable units of analysis, given the inherently different dynamics of these two data collection settings. However, because of the exploratory nature of this study, as well as the fact that focus group participants told both personal and anecdotal stories (as opposed to merely discussing attitudes and larger social norms), we mix interviewee and focus group data in our presentation of results.

RESULTS

Of the 40 focus group participants, 19 were current university students, and 21 were women from the community. Among the 12 interviewees, four were university students, and eight were women from the community. Focus group participants and interviewees represented a range of racial, ethnic and educational backgrounds, * and described six themes pertaining to sexual aspects of the IUD (Figure 1). For retention’s sake, we have created an organization scheme in which all themes begin with the letter “s”: security, spontaneity, sexual aspects of bleeding and cramping, scarcity of hormones, string and stasis.

FIGURE 1.

Themes on the sexual aspects of the IUD that emerged from focus group discussions and interviews with women aged 18–29, Dane County, Wisconsin, 2014

Security

Many respondents spoke about the sexual benefits of feeling extremely protected against pregnancy, which supports the notion that the sexual aspects of contraceptives can be psychological and not merely physiological. The security theme was shared by ever- and never-users of the IUD, but was especially common among the latter as an anticipated benefit of the method. A number of women, noting chronic concern about unintended pregnancy, described how the IUD could greatly minimize this concern and, thus, reduce sexual inhibition. Participants often compared the IUD favorably with oral contraceptives or condoms in terms of its ability to provide “peace of mind.”

Along similar lines, participants sometimes described how the security of the IUD could minimize “that little voice inside your head”—that is, chronic worry that one might be or become pregnant. In response to the question about how the IUD might affect sexuality, a university interviewee and IUD ever-user reported:

“I guess the peace of mind is the greatest thing, because you don’t have to worry, like, have that minor panic attack, like, ‘Oh my god, I can get pregnant.’ I know I have a solid five-year method….I mean there’s just that peace of mind that now you get to have, I don’t know, lots of sex fun and not have to worry about a baby.”

Never-users expressed similar psychological benefits from the security of the IUD. One community focus group participant, a never-user with interest in the copper IUD, said:

“[With the IUD], there’s just not as much worry….No one likes when you’re in the mood and you’re in the middle of something, having to worry about ‘Oh, did I take my pill today? Should we use a condom for backup?’”

Two other never-users from different community focus groups also described how the security afforded by the IUD’s efficacy could indirectly enhance sexual well-being. One said, “Knowing you’re protected against pregnancy might improve your sex life.” The other commented, “The IUD could affect your sex life indirectly, just like knowing it’s already there and you don’t have to take care of anything. That’s a big thing.” And a never-user in a university focus group said:

“I would think [the IUD] could probably enhance [your sex life] because…you don’t have to worry about ‘Oh, have I taken my pill today?’ or ‘I have to go put a condom on.’ It’s just always there, so you’re always protected.”

Finally, a university focus group participant and never-user described how a friend was sexually active but highly motivated to avoid pregnancy, and how the security of the IUD helped this friend maximize her sexual well-being and enjoyment:

“I do have one friend who’s using [the IUD], and I know she really enjoys it for her lifestyle. Like, she has a lot of sex with a lot of people, and for her, it’s a really big relief knowing it’s in place. She’ll use it with other stuff [condoms], like if it’s a person she doesn’t know, but she definitely feels that it’s a relief that she can have sex like that and not worry about pregnancy.”

Spontaneity

Both ever- and never-users compared the IUD favorably to condoms, particularly in terms of how the method facilitates spontaneous and free-flowing sexual encounters. Participants recognized the importance of condoms for protection against STDs; however, a number of young women reported using condoms less for STD prevention than for extra pregnancy protection or as a backup method if they missed taking pills. In such cases, the IUD ranked higher than condoms in terms of sexual spontaneity.

For example, when asked about any changes in her sex life due to her IUD use, one university interviewee responded, “I’d say it’s better….if we don’t have [condoms], then it’s something I don’t have to worry about.” Similarly, another university interviewee said, “I guess [the IUD] increased the spontaneity, because we didn’t exactly have to use a condom if we didn’t want to. So, I guess sex was a little bit more fun in that way.” Finally, in regard to whether she had noticed any differences in her sex life as a result of her IUD use, a community interviewee said:

“I guess so. Not having to use a condom or having to put something in you or…worry about that that way. You know, you can just have sex whenever without worrying, so that’s positive.”

Never-users similarly anticipated sexual spontaneity benefits of the IUD. For example, a university focus group participant and never-user said, “[The IUD] doesn’t get in the way during sex. You don’t have to be like, ‘Hold on, let me go put my female condom in.’”

Young women repeatedly stated the importance of condoms in preventing STDs, particularly at the beginning of relationships or with multiple partners; however, their comments underscored their preferences for free-flowing sexual encounters. Both in women’s actual and in their anticipated experiences, the IUD had more potential than other methods—particularly condoms—to help people achieve their spontaneous sexual ideal.

Sexual Effects of Bleeding and Cramping

Clinical research has documented bleeding and cramping associated with use of copper and hormonal IUDs;24,25 fewer studies have considered such side effects within a sexual context. Participants in our study described how increased or unscheduled bleeding and cramping could be unpleasant. No IUD ever-users mentioned this particular theme; however, never-users noted how one’s sex life could be negatively affected by such side effects. For example, one university focus group participant said:

“One of my closest friends, like, had her period for four solid months after she got [her IUD] implanted. So that would obviously be a pretty big deterrent on your sex life if you, like, had your period for a very extended amount of time or if you’re cramping for a while after getting it implanted.”

Some never-users also expressed concern about how one’s bleeding could change after an IUD is placed. Some respondents characterized this “not knowing” as a potential sexual deterrent and a reason to avoid the method. In this regard, participants compared the IUD unfavorably to oral contraceptives, which tend to lighten bleeding and cramping for almost all users.26 For example, one never-user and university focus group participant said:

“[The IUD’s] so unreliable in the sense of you don’t know if your period’s going to go crazy. And I would hate for that to affect my sex life with my boyfriend right now. So, I think that would be a really big deterrent for me.”

Few participants—regardless of IUD experience—mentioned the sexual aspects of the reductions in bleeding and cramping that frequently happen with use of the hormonal IUD in particular. One community focus group never-user said:

“If you had less bleeding with [a hormonal IUD]…you wouldn’t really have to communicate with your partner about your menstrual cycle. That form of communication is…eck. So, it’s good that you can avoid that.”

Scarcity of Hormones

A number of never-users reported the IUD’s potential to improve, or at least not worsen, women’s sexual experiences, because it contains a low level of hormones or none at all; no ever-users described this phenomenon. Several never-users felt that the hormonal dosages and configurations in the pill, patch and ring could detract from one’s sex life. In comparison, the IUD—particularly the copper IUD—could have a more positive sexual effect. For example, a community focus group participant reported: “[The question about sexual effects] makes me think of the IUD, especially the copper one, because ever since I’ve been on hormonal birth control, my sex drive has dropped a ton.”

Along similar lines, a community focus group participant said:

“And maybe the lack of hormones [could improve your sex life]. I don’t know how certain people react to certain hormones and levels and all that stuff. I mean, it’s something that is just you and a piece of copper, so that could be better for some people.”

Finally, a never-user and university focus group participant said, “I think knowing that [the IUD] has way less hormones makes me less nervous that it would affect my sex life at all.”

String (Effect on Partner)

When young women were probed with questions about IUDs and sexuality, their most common first response was not about their own sexual experience, but about their male partners’; we list this theme fifth, however, because our focus is women’s sexual experiences. Both focus group and interview participants described personal and anecdotal situations in which a partner’s penis had been bothered by the string of an IUD. For example, one community focus group participant and former IUD user reported:

“I had an issue with my partner where the strings of the IUD would poke him….My nurse was like ‘Oh, that’s no problem. We’ll just cut them shorter.’ And I was like ‘That’s not going to help.’ I don’t know. I just felt like it wouldn’t help me. So I felt like that was one negative thing about the IUD that I didn’t really like.”

A community interviewee and current IUD user relayed a similar experience:

“When I first got [my IUD], my partner said it poked him in the urethra, which was quite painful. So, it kind of killed the moment. Yeah, it was just the first time, and he’s like ‘HUUUUUUUHHHH!’ And I was like ‘Oh my god. What happened? Did it bite you? Like, what happened?’ So that can happen….I felt bad. I imagine that’s very painful. Urethras don’t like bring poked, generally speaking.”

In contrast to the previous case, however, this one-time experience did not cause the woman to discontinue using the IUD; she was a highly satisfied IUD user at the time of data collection.

Several women who had never used an IUD still cited the potential of string-related discomfort for their partners. One university focus group participant reported, “I heard, like, online…there’s a string involved…that can hurt the guy? Like, that’s another horror story that I’ve heard.” A community focus group participant said her concern about the string would mean she would have to let a new partner know about her IUD use:

“I think the IUD’s the only one where I would really consult with my partner about it, because I’ve heard that partners can feel it, like with penetration….That sounds terrifying. I don’t think if I had a penis, I’d want something poking it at the end.”

At a different point in the focus group, this same participant said:

“I had a friend who had a horrible experience with her boyfriend where he, like, screamed out in pain in the middle of sex and, like, it scarred her. And she, like, actually went and changed her IUD after that.”

Notably, interviewees—all of whom had used an IUD—were less likely than focus group participants to mention this phenomenon. Anecdotal reports of string issues were more common than personal experiences, especially in focus groups, in which participants built upon each others’ stories. Nonetheless, this theme was the most top-of-mind sexual aspect of the IUD for most participants in both focus groups and interviews.

Stasis: No Sexual Change

This last theme pertains to no sexual change, or stasis. Ever-user interviewees were especially likely to indicate that their IUD use had had no sexual effect—perhaps because these women were not in focus groups, in which their thoughts could be spurred by other participants’ comments. For several women, the interview seemed to be the first time they had reflected on this issue. One ever-user university interviewee said:

“I honestly don’t think the IUD’s affected [my sex life] at all…in terms of like, my sex drive….If anything, it’s increased it, but I don’t think that’s directly related to the IUD.”

Similarly, an ever-user community interviewee said:

“I have not noticed any difference [with the IUD] at all, either enhancing or detracting from [my sex life]….I’m pretty free anyways, so I haven’t noticed a difference.”

Other interviewees reported that although their IUD use had led to no sexual change, no change was better than the negative change they had experienced when using other methods. For example, a university interviewee reported the following:

“I don’t like condoms, and obviously neither does my partner. Most guys are not a big fan of condoms. But with the IUD, I feel a lot more comfortable using them less, which is good for me. The IUD itself, I don’t really feel like affects my sex life at all. But condoms, I feel, really do.”

This respondent clarified that she had been using condoms for extra pregnancy protection, not for STD protection. As a pill user, she worried when she did not take her pill at exactly the same time every day, so condoms occasionally served as a backup contraceptive method. In comparison, the IUD helped diminish concerns about user error; therefore, she felt she no longer needed condoms as a backup.

DISCUSSION

Despite the outpouring of research and policy efforts regarding the IUD, we know little about how using the method may affect women’s sexual experiences, which in turn may affect method continuation and, ultimately, effectiveness. Although the reproductive health field needs more quantitative, longitudinal data on the IUD’s sexual acceptability, qualitative research is a vital first step in documenting the various sexual aspects of this and other methods, particularly when clients can describe those sexual dimensions in their own words. Case in point, our study revealed a number of themes relating to the IUD’s sexual acceptability that might have been missed by a quantitative measure such as the Female Sexual Function Index.17 Examples include respondents’ reports of the psychosexual benefits of the IUD’s efficacy and its relatively low hormone level—both of which can contribute to overall sexual well-being. Along these lines, our findings suggest that the IUD has the potential to improve the sexual well-being of some women—and they are consistent with results of more classic sexual functioning studies in other countries suggesting that IUD use is more likely to enhance than to detract from women’s sexual experience.16

In regard to the broader concept of sexual acceptability of all contraceptive methods, our findings were consistent with prior qualitative work on the sexual dimensions of contraceptives, including the effect on partners’ pleasure7,9 and the “sexual aesthetics” of contraceptive side effects involving bleeding and cramping.7 Together, these studies suggest that a patient-centered approach to the sexual acceptability of contraceptives should go beyond measures of sexual function to document and address the sexual aspects most noteworthy to clients themselves. Although sexual enjoyment is contingent upon physiological responses such as arousal, lubrication and orgasm, these take place within relational and psychological contexts that may be more important or top-of-mind to women. In fact, no respondent in our study mentioned such physiological functions when asked about the potential sexual aspects of IUDs.

Of course, the more indirect, psychological and otherwise qualitative aspects of sexual acceptability can be more complex and harder to measure than classic sexual functioning. Such complexity, however, should not discourage researchers, program planners or educators from directly addressing phenomena so central to actual contraceptive users—who, after all, have sex not to use contraceptives, but for a range of sexual, relational and personal reasons. Without trying to understand contraceptives in the sexual contexts in which they are used, we risk missing critical components of overall acceptability and women’s willingness to both try and continue any given method. A better understanding of the sexual aspects of contraceptives—and of the IUD, in particular—could strengthen counseling, marketing and education efforts. For example, by highlighting the sexual disinhibition benefits associated with very effective methods, counselors could help encourage use of the IUD. Or by acknowledging that contraceptive users want methods that enhance their sexual well-being (or at least do not undermine it), researchers, program planners and educators may be more likely to take a patient-centered approach to their work, and more specifically, to efforts to promote the IUD.

However, family planning researchers and practitioners (e.g., providers, counselors, advocates) are hardly the only ones who can fail to acknowledge the sexual aspects of contraceptives. Actual contraceptive users do not always have the wherewithal or the words to describe their method’s sexual acceptability. After all, sexual acceptability is only one of many factors that can influence people’s uptake and experience of contraceptives.27 For example, a number of our study participants appeared not to have considered the sexual aspects of their devices until we asked about them. Even though contraceptives are designed expressly for sexual activity, our culture’s medical approach to contraception may discourage women from regularly thinking of contraceptives in a sexual way.

We were surprised by our finding that of all the possible sexual aspects of the IUD, the one on the top of many respondents’ mind—the string—was the one that affects their partners, not themselves. This finding supports previous feminist sexuality research, which has described how women are socialized to be more partner-oriented in sex than men, as well as how women are less likely than men to be encouraged to develop their own sexual subjectivity or perceived right to sexual pleasure.28 For example, in many heterosexual couples, female orgasm is pleasing, but ultimately incidental compared with male orgasm.29 We argue that practitioners and researchers could do far more to document and address contraceptives’ sexual acceptability; however, larger cultural shifts are also needed to increase women’s own claim to sexually acceptable methods, as well as their inherent right to sexual well-being and not merely the absence of disease or dysfunction.30

Limitations

Findings of this study should be considered in light of its limitations. These data cannot be used to determine definitively whether the IUD had a positive, negative or neutral affect on women’s sexual experiences and well-being. After all, qualitative methods are best suited to finding the dimensions and nuance involved in a particular theme or concept. We were interested in documenting how women described the IUD in relation to their sexuality (both experienced and anticipated), not in confirming the proportion of women who described the IUD as sexually acceptable or unacceptable, or in determining the degree to which particular themes outweighed others in importance. Nonetheless, future clinical studies would be well served by including measures that allow for comparisons in sexual changes due to use of the hormonal IUD, the copper IUD, other methods or no method at all. Another potential limitation is that never-users’ reports on the sexual aspects of the IUD are, of course, speculative. Although we argue that such speculative reports are important, given their likelihood of shaping contraceptive clients’ willingness to use the IUD, results should nonetheless be interpreted accordingly.

Conclusions

In this qualitative study with young adult women, we found that the IUD has the potential to improve women’s sexual well-being through a number of mechanisms, particularly by enhancing security and spontaneity, and by exposing users to a low level of libido-affecting hormones. These sexual benefits seem to be associated with the IUD’s overall acceptability or people’s willingness to use the method in the future. However, some never-users also expressed concern about the sexual effects of increased bleeding and cramping caused by the IUD, as well as partners’ being able to feel the string. Although additional research is needed, researchers and practitioners may wish to tap into the sexual benefits of the IUD in their counseling and social marketing efforts. They may also wish to directly assess and address clients’ potential sexual concerns about the method.

Acknowledgments

Data collection and manuscript preparation were supported by grant K12 HD055894 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Additional support came from NICHD Population Research Infrastructure grant P2C HD047873, as well as two grants from the University of Wisconsin–Madison—one from the Obstetrics and Gynecology Intramural Research Fund and one from the Graduate School. The content of this article is the responsibility solely of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding organizations.

Footnotes

We use “participants” and “respondents” interchangeably to refer to any person who took part in the study.

Contributor Information

Jenny A. Higgins, Email: jenny.a.higgins@wisc.edu, Department of Gender and Women’s Studies, University of Wisconsin–Madison..

Kristin Ryder, Department of Gender and Women’s Studies, University of Wisconsin–Madison..

Grace Skarda, Department of Gender and Women’s Studies, University of Wisconsin–Madison..

Erica Koepsel, Department of Gender and Women’s Studies, University of Wisconsin–Madison..

Eliza A. Bennett, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison..

REFERENCES

- 1.Severy LJ, Newcomer S. Critical issues in contraceptive and STI acceptability research. Journal of Social Issues. 2005;61(1):45–65. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higgins JA, Hirsch JS. The pleasure deficit: revisiting the “sexuality connection” in reproductive health. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2007;39(4):240–247. doi: 10.1363/3924007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins JA, Davis AR. Contraceptive sex acceptability: a commentary, synopsis and agenda for future research. Contraception. 2014;90(1):4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith NK, Jozkowski KN, Sanders SA. Hormonal contraception and female pain, orgasm and sexual pleasure. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2014;11(2):462–470. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis AR, Castaño PM. Oral contraceptives and libido in women. Annual Review of Sex Research. 2004;15(1):297–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham CA, et al. Does oral contraceptive–induced reduction in free testosterone adversely affect the sexuality or mood of women? Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(3):246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higgins JA, Hirsch JS. Pleasure, power, and inequality: incorporating sexuality into research on contraceptive use. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(10):1803–1813. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins JA, et al. Relationships between condoms, hormonal methods, and sexual pleasure and satisfaction: an exploratory analysis from the Women’s Well-Being and Sexuality Study. Sexual Health. 2008;5(4):321–330. doi: 10.1071/sh08021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fennell J. “And isn’t that the point?”: pleasure and contraceptive decisions. Contraception. 2014;89(4):264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Secura GM, et al. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2010;203(2):115.e1–115.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ricketts S, Klingler G, Schwalberg R. Game change in Colorado: widespread use of long-acting reversible contraceptives and rapid decline in births among young, low-income women. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2014;46(3):125–132. doi: 10.1363/46e1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harper CC, et al. Challenges in translating evidence to practice: the provision of intrauterine contraception. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2008;111(6):1359–1369. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318173fd83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hubacher D, et al. The impact of clinician education on IUD uptake, knowledge and attitudes: results of a randomized trial. Contraception. 2006;73(6):628–633. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kavanaugh ML, et al. Meeting the contraceptive needs of teens and young adults: youth-friendly and long-acting reversible contraceptive services in U.S. family planning facilities. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52(3):284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.10.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenberg D, McNicholas C, Peipert JF. Cost as a barrier to long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) use in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52(Suppl. 4):S59–S63. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanders JN, Smith NK, Higgins JA. The intimate link: a systematic review of highly effective reversible contraception and women’s sexual experience. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2014;57(4):777–789. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosen R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2000;26(2):191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl. 1):S43–S48. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15–44: United States, 2011–2013. NCHS Data Brief. 2014 No. 173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Bureau of the Census. State and country quick facts. 2015 http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html.

- 21.Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. second ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ulin PR, et al. Qualitative Methods: A Field Guide for Applied Research in Sexual and Reproductive Health. Research Triangle Park, NC: Family Health International; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. second ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acuña MJ, et al. A comparative study of the sexual function of institutionalized patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010;7(10):3414–3423. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andrade AT, et al. Assessment of menstrual blood loss in Brazilian users of the frameless copper-releasing IUD with copper surface area of 330mm2 and the frameless levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2004;70(2):173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatcher RA, et al., editors. Contraceptive Technology. 20th ed. New York: Ardent Media; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson N, et al. Women’s social communication about IUDs: a?qualitative?analysis. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2014;46(3):141–148. doi: 10.1363/46e1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katz-Wise S, Hyde J. Sexuality and gender: the interplay. In: Tolman DL, Diamond LM, editors. APA Handbook of Sexuality and Psychology Vol. 1: Person-Based Approaches. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2014. pp. 29–62. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wade LD, Kremer EC, Brown J. The incidental orgasm: the presence of clitoral knowledge and the absence of orgasm for women. Women & Health. 2005;42(1):117–138. doi: 10.1300/J013v42n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO definition of sexual health. 2015 http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/sexual_health/sh_definitions/en/.