Key Points

Telomerase variants in patients with bone marrow failure syndromes are difficult to categorize as disease-causing or otherwise.

DC can derive from triallelic mutations in 2 telomerase genes and epigenetic-like inheritance of short telomeres.

Abstract

Dyskeratosis congenita (DC) and related diseases are a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by impaired telomere maintenance, known collectively as the telomeropathies. Disease-causing variants have been identified in 10 telomere-related genes including the reverse transcriptase (TERT) and the RNA component (TERC) of the telomerase complex. Variants in TERC and TERT can impede telomere elongation causing stem cells to enter premature replicative senescence and/or apoptosis as telomeres become critically short. This explains the major impact of the disease on highly proliferative tissues such as the bone marrow and skin. However, telomerase variants are not always fully penetrant and in some families disease-causing variants are seen in asymptomatic family members. As a result, determining the pathogenic status of newly identified variants in TERC or TERT can be quite challenging. Over a 3-year period, we have identified 26 telomerase variants (16 of which are novel) in 23 families. Additional investigations (including family segregation and functional studies) enabled these to be categorized into 3 groups: (1) disease-causing (n = 15), (2) uncertain status (n = 6), and (3) bystanders (n = 5). Remarkably, this process has also enabled us to identify families with novel mechanisms of inheriting human telomeropathies. These include triallelic mutations, involving 2 different telomerase genes, and an epigenetic-like inheritance of short telomeres in the absence of a telomerase mutation. This study therefore highlights that telomerase variants have highly variable functional and clinical manifestations and require thorough investigation to assess their pathogenic contribution.

Introduction

The telomeropathies are a collection of disorders characterized by impaired telomere maintenance.1,2 The classic example of this is the inherited bone marrow failure (BMF) syndrome dyskeratosis congenita (DC).3 In this disease, patients are diagnosed by the presence of a characteristic triad of mucocutaneous features (abnormal skin pigmentation, nail dystrophy, and oral leukoplakia) which is often seen alongside BMF and other constitutional features which can affect all body systems. The Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome (HHS) is a particularly severe form of DC characterized by aplastic anemia (AA), immune deficiency, growth retardation, microcephaly, and cerebellar hypoplasia.4

DC and HHS patients usually have abnormally short telomeres due to variants in genes encoding proteins and an RNA molecule responsible for telomere extension and maintenance.5,6 Human telomeres are composed of thousands of repeats of the hexameric sequence TTAGGG. These chromosomal caps serve to protect genomic DNA from attrition during cell division due to the “end replication problem,”7 which results in the loss of 50 to 100 bp of telomeric DNA during each cycle. When telomeres become critically short, replicative senescence is triggered, halting further divisions of the cell.8 In some stem cells and in the germline, telomere shortening can be compensated by the action of telomerase.9 This ribonucleoprotein complex is composed of 2 key components, the reverse transcriptase (TERT) and the RNA component (TERC). TERT is responsible for lengthening telomeres using the RNA template provided by TERC. In association with proteins of the shelterin complex, telomeres also prevent the chromosome ends from being recognized as a double-strand breaks and being inappropriately subjected to DNA damage repair mechanisms.10

Genetic variants in TERC and TERT are frequently seen in DC patients, accounting for ∼10% of cases.11 Typically, TERC variants are heterozygous, resulting in dominantly inherited disease with heterogeneous disease presentation. Alongside the typical mucocutaneous and BMF features of DC,12 patients have also been observed presenting with AA, myelodysplasia (MDS),13 pulmonary fibrosis,14 and/or liver disease.15 Similarly, dominantly inherited variants in TERT have been identified in DC patients16,17 as well as in patients with idiopathic or familial AA,18 pulmonary fibrosis,14,19 liver disease,20 and familial MDS/acute myeloid leukemia (AML).15,21

Although TERC and TERT variants are associated with a number of disease phenotypes, the investigation of telomerase variants is further complicated by variable penetrance within families, late onset of disease, subclinical features, and disease anticipation due to progressive telomere shortening through successive generations.17,22 Furthermore, next-generation sequencing has increased our awareness of the number of genetic variants in healthy individuals, with ∼100 novel, heterozygous coding variants being described in each person. Data from the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/) indicates that 1 in ∼120 people carry a rare missense or loss-of-function (LOF) variant (allele frequency <1/10 000) in the TERT gene. The ExAC database shows genetic variants reported in 60 706 unrelated individuals, sequenced as part of various disease-specific and population genetic studies. This underlies the importance of investigating novel variants in order to assign their pathogenic status.

Here, we report on 23 families with DC or DC-like disease in which we have identified 26 telomerase variants, 16 of which are novel. From analyzing each variant, we have predicted their impact and placed them into 3 different categories: disease-causing, status uncertain, and bystander. We provide an algorithm which will assist in categorizing new telomerase variants and report on 2 novel inheritance mechanisms at play in causing telomeropathies.

Methods

Patient selection

The majority of patients included in this study come from the DC registry (DCR) in London, which currently comprises 417 families with 618 affected individuals from 42 different countries. The criteria for admission to the DCR has been described previously.23 In addition to these patients, we have also studied samples from patients who have clinical features that overlap DC, but not enough to fulfill a definitive diagnosis, as well as patients who present with AA, with or without additional constitutional features (CAA). Informed consent was provided from all patients and family members in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. These studies have received approval from the East London and The City Research Ethics Committee.

Identification of telomerase variants

Telomerase variants were identified in patients recruited over the past 3 years using 3 different methods: (1) all BMF patients referred to our laboratory (n = 338) were routinely screened for TERC variants by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and direct Sanger sequencing using a BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing V3.1 kit followed by capillary electrophoresis on a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). (2) Screening for TERT variants was performed on a selected group of patients (n = 39) whose clinical presentation had features indicative of a telomerase variant, including DC and BMF with autosomal-dominant inheritance, pulmonary fibrosis, and/or liver disease. The 16 exons of TERT were amplified on 18 different fragments by PCR and scanned for mutation by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a WAVE DNA fragment analysis system (Transgenomic), as described previously.16 If a sample gave an abnormal elution pattern, the appropriate fragment was reamplified and sequenced as for the TERC fragment above. (3) In another group of DC patients, or patients with DC-like features (n = 75), we have performed whole-exome sequencing as described elsewhere.24 Briefly, library preparation and exon capture was performed using the TruSeq Exome enrichment kit (Illumina). Samples were sequenced on the Illumina HighSequation 2000 following the on-system generation of 100-bp paired-end reads and variants were called with the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) version 2.7.4.

Telomere length measurement

Patient telomere lengths (TLs) were measured using a monochrome multiplex quantitative PCR method.25 This approach compares the amount of PCR product generated from the telomere (T) to a single-copy gene (S) to obtain a T:S ratio, which is proportional to TL. In brief, 30 nM of telomere-specific primers and 6 nM of primers specific to human β-globin were used, 10 ng of genomic DNA was input per sample (extracted from whole peripheral blood), and all samples were measured in triplicate. Reactions were analyzed on a Roche LightCycler 480 real-time thermal cycler (Roche Applied Science). Standard curves for telomere and human β-globin amplification were established by titration of a reference DNA sample. T:S ratios were determined from these curves and normalized to the T:S ratio of a second reference sample run on each plate. Selected samples also had TL measured by flow–fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH; Repeat Diagnostics).

Cell culture and plasmids

Telomerase-negative WI38-VA13 cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Wild-type pcDNA3.1+TERC or pcDNA3.1+TERT plasmids have been previously reported.21 Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out in order to introduce single-nucleotide variants into these plasmids using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Scientific). The fidelity of all constructs was verified by DNA sequencing.

Analysis of telomerase activity

The effect of TERC and TERT variants on telomerase activity was measured using the TRAPeze RT Telomerase Detection kit (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. The telomerase-negative human fibroblast cell line WI-38 and plasmids pcDNA3.1+TERT and pcDNA3.1+TERC were used. Briefly, 1 × 105 WI-38 cells were transfected with 0.8 µg of DNA (0.4 µg of each pcDNA3.1-TERT and pcDNA3.1-TERC) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and harvested 24 hours later. The telomerase activity of 3000 cells was measured in duplicate in 2 independent experiments. Plasmid expression was confirmed as described previously.21

Results

Identification of telomerase variants

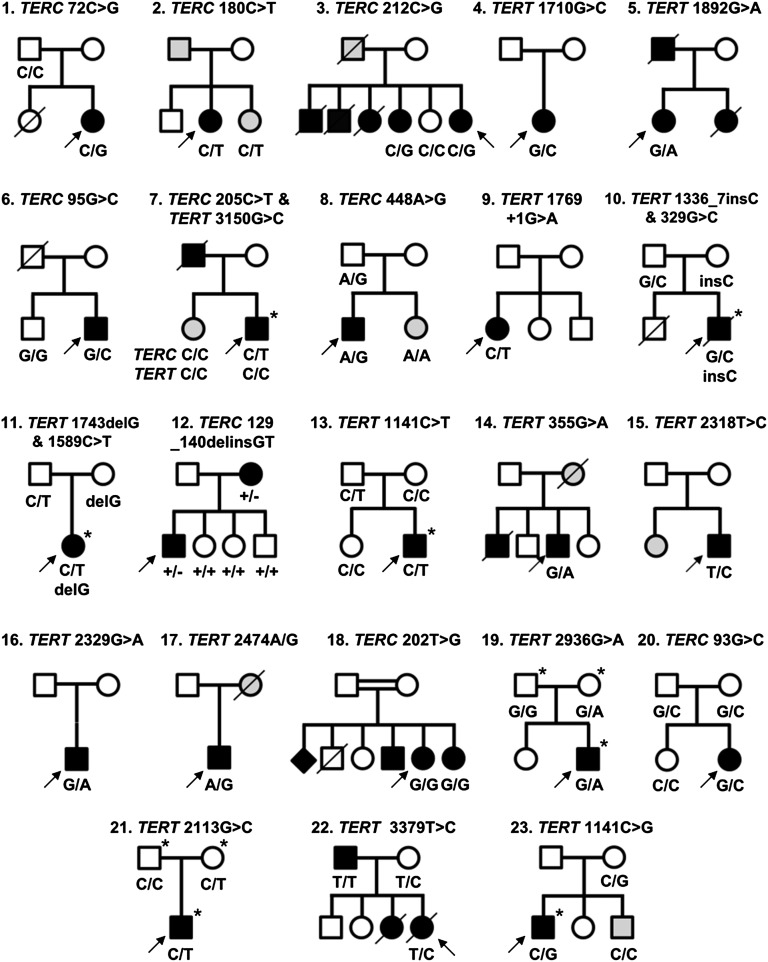

Direct sequencing of the TERC gene has revealed 9 variants of interest among the 338 patients screened in this study, 5 of which have not been observed previously. Scanning of the TERT gene by denaturing HPLC has identified 7 cases with heterozygous variants from a selected cohort of 39 patients. Whole-exome sequencing, performed on a total of 75 patients, has revealed 9 additional TERT variants to give a total of 16 TERT variants and 9 TERC variants in 23 different families (Figure 1; Table 1). We have also obtained updated clinical information from a family with a TERT variant that we have previously reported,16 and this will be discussed further.

Figure 1.

Twenty-three families identified with telomerase variants. Open circles and squares indicate unaffected females and males; black circles and squares, affected females and males; gray circles and squares, females and males with few disease features; diamond, gender unknown; line through, deceased. Arrows indicate the index cases in each family. Where known, the genotype is indicated below each individual. Individuals who have undergone exome sequencing are denoted with an asterisk (*).

Table 1.

Twenty-six telomerase variants in 23 families

| Family | Sex | Age at report, y | Gene | Nucleotide change | Amino acid substitution | Zygosity | TRAP, % | Frequency on ExAC | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 48 | TERC | r.72C>G | N/A | Het | 5* | NR | D |

| 2 | Female | 32 | TERC | r.180C>T | N/A | Het | 25* | NR | D |

| 3 | Female | 53 | TERC | r. 212C>G | N/A | Het | 1* | NR | D |

| 4 | Male | 37 | TERT | c.1710G>C | p. Lys570Asn | Het | 1-2* | NR | D |

| 5 | Female | 64 | TERT | c.1892G>A | p.Arg631Gln | Het | 2.7 | NR | D |

| 6 | Male | 42 | TERC | r.95G>C | N/A | Het | 1.7 | NR | D |

| 7 | Male | 54 | TERC | r.205C>T | N/A | Het | 4.7 | NR | D |

| 8 | Male | 12 | TERC | r.448A>G | N/A | Het | 2.7 | NR | D |

| 9 | Female | 39 | TERT | c.1769+1G>A | Splicing | Het | NA | NR | D |

| 10 | Male | 4 | TERT | c.1336_1337insC | p.Arg446Profs*93 | C. het | NA | NR | D |

| 11 | Female | 25 | TERT | c.1743delG | p.Trp581* | C. het | NA | NR | D |

| 12 | Male | 11 | TERC | c. 129_140delinsGT | N/A | Het | NA | NR | D |

| 10 | Male | 4 | TERT | c.329G>C | p.Gly110Ala | C. het | NA | NR | D |

| 13 | Male | 3 | TERT | c.1141C>T | p.Arg381Cys | Het | 66 | NR | U |

| 14 | Male | 49 | TERT | c.355G>A | p.Val119Met | Het | 140 | NR | U |

| 15 | Male | 29 | TERT | c.2318T>C | p.Met773Thr | Het | NA | NR | U |

| 16 | Male | 45 | TERT | c.2329G>A | p.Val777Leu | Het | NA | NR | U |

| 17 | Male | 40 | TERT | c.2474A>G | p.Tyr825Cys | Het | NA | NR | U |

| 18 | Female | 58 | TERC | r.202T>G | N/A | Hom | 92 | NR | U |

| 11 | Female | 25 | TERT | c.1589C>T | p.Pro530Leu | C. het | NA | 2/121934 | B |

| 19 | Male | 2 | TERT | c.2936G>A | p.Arg979Gln | Het | 35 | 1/122330 | B |

| 20 | Female | 14 | TERC | r.93G>C | N/A | Het | NA | 2/112256 | B |

| 21 | Female | 5 | TERT | c.2113G>C | p.Glu705Gln | Het | 38 | NR | B |

| 22 | Female | 5 | TERT | c.3379T>C | p.Phe1127Leu | Het | 100 | NR | B |

| 7 | Male | 54 | TERT | c.3150G>C | p.Lys1050Asn | Hom | 56 | 10/114130 | D |

| 23 | Male | 17 | TERT | c.1141C>G | p.Arg381Gly | Het | 51 | NR | D |

B, bystander; C.het, compound heterozygous; D, disease-causing; Het, heterozygous; Hom, homozygous; N/A, not applicable; NA, not available; NR, not reported; TRAP, telomerase repeat amplification assay (% wild type); U, uncertain status.

Reported elsewhere.

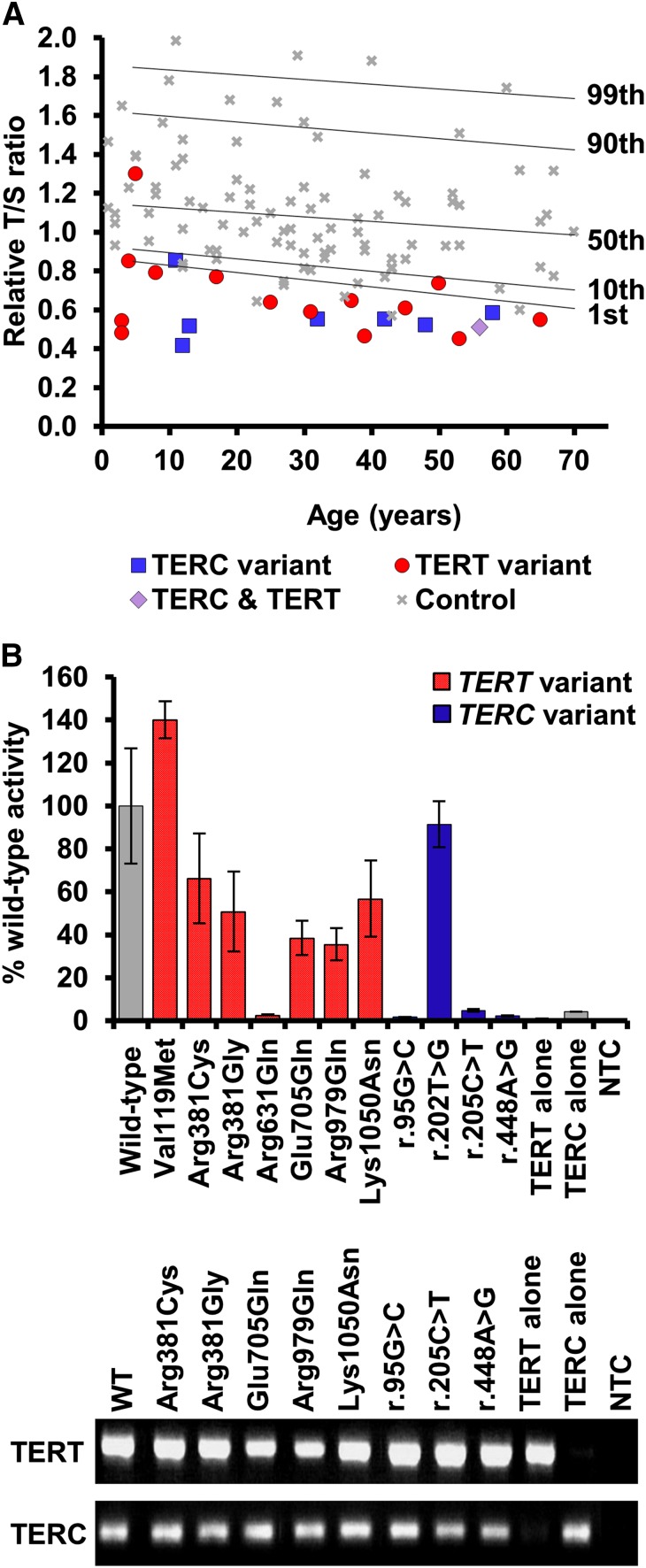

The TLs of all patients were measured (Figure 2A) except for the index in family 17 who was excluded as the DNA was not of sufficient quality. With the exception of family 21, all probands had short telomeres (below the 10th centile) and 18 had very short telomeres (below the first centile). Although this is indicative of a telomeropathy (as demonstrated previously21,26-28), we examined each family further, and find that it is not always easy to definitively assign pathogenic status to the telomerase variants we identified.

Figure 2.

Telomere lengths of patients and telomerase activity of selected variants. (A) Telomere lengths were measured by MM-qPCR and expressed as a T:S ratio for probands and 99 normal controls. Percentiles for the normal controls are indicated. All samples were normalized to a reference. (B) Telomerase activity was measured in WI38-VA13 cells ectopically expressing the stated telomerase variant. Activity was calculated as a percentage of wild-type levels, measured using the TRAP. Less than 5% activity is considered LOF. RT-PCR products demonstrate expression of wild-type and mutant TERC and TERT mRNA. Bars show standard error of mean of duplicate readings from 2 independent experiments. MM-qPCR, monochrome multiplex quantitative PCR; mRNA, messenger RNA; NTC, no template control; RT-PCR, reverse transcription PCR.

Disease-causing variants

We consider a variant to be disease-causing if it has been previously reported as disease-associated. This is true for 3 of the TERC variants (r.72C>G, r.180C>T, and r.212C>G) and 2 of the TERT variants (Lys570Asn and p.Arg631Gln) that we have identified in families 1 through 5. Arg631Gln in family 5 is worthy of special mention as it has been reported previously on 4 different occasions, segregating with a variety of phenotypes including DC-like disease, familial MDS/AML, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.21,29-31 It is also 1 of the few TERT variants that, in our hands, gives telomerase activity of <10% in the telomerase repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) assay, which we have confirmed in this study (Figure 2B). For the other variants, the fact that they are recurring in affected individuals strengthens the case that they are disease-causing.

We also consider LOF variants to be disease-causing as these will certainly result in haploinsufficiency which is a well-established disease mechanism with telomerase variants.18,32-34 We suggest that a telomerase activity of < 5% of wild-type levels in a TRAP assay represents LOF. This is true for 3 novel TERC variants (r.95G>C, r.205C>T, and r.448A>G) identified in families 6 through 8. Interestingly, apart from p.Arg631Gln, none of the TERT missense variants that we have studied here display low TRAP activity (Figure 2B). However, we have identified 3 TERT variants in families 9 through 11 that are predicted to result in LOF in that they are splicing, frameshift, or nonsense variants (c.1769+1G>A, p.Arg446Profs*93, and p.Trp581*, respectively).35 In family 12, we have identified a TERC variant (r.129_140delinsGT) that is also predicted to cause LOF due to its impact on the pseudoknot domain.

The index case in family 10 presented with severe features resembling HHS, including microcephaly and cerebellar atrophy (Table 2). In addition to the LOF TERT variant (p.Arg446Profs*93) inherited from his asymptomatic mother, he also inherited a novel missense variant from his asymptomatic father (p.Gly110Ala). This situation is very reminiscent of previous reports of a severe phenotype being associated with biallelic inheritance of TERT variants36,37 and we therefore consider it likely that both of these variants are contributing to the disease. Furthermore, exome sequencing did not reveal rare variants in any other gene known to cause DC, or to be involved in telomere biology.

Table 2.

Clinical features of probands and affected family members

| Family | Individual | Hematologic features | Mucocutaneous features | Other abnormalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Index | MDS | FH ovarian and prostate cancer | |

| 2 | Index | BMF | FH macrocytic anemia | |

| 3 | Index | BMF | ||

| 3 | Brother | BMF | LD, finger clubbing | |

| 3 | Brother | BMF | Premature greying, hair loss | |

| 3 | Sister | Low wbc | PF | |

| 4 | Index | BMF | LD, PF, premature greying, hair loss | |

| 5 | Index | ND, SP | PF, premature greying | |

| 5 | Father | BMF | LD, premature greying | |

| 5 | Sister | BMF | COPD, premature greying | |

| 6 | Index | BMF | ||

| 7 | Index | BMF | ND, SP | Dental, renal failure |

| 7 | Sister | BMF | ND | |

| 7 | Father | ND | ||

| 8 | Index | BMF | CH, MC, ataxia | |

| 8 | Sister | CH, MC | ||

| 9 | Index | AML | ND | Hair loss |

| 10 | Index | BMF | ND, LP | CH, MC |

| 11 | Index | BMF | LP | Dental, aseptic necrosis, tongue cancer |

| 12 | Index | BMF | ||

| 12 | Mother | BMF | ||

| 13 | Index | BMF | ND, LP | Low birth weight |

| 14 | Index | BMF | LD, PF, dental | |

| 14 | Brother | LD, PF | ||

| 14 | Mother | PF | ||

| 15 | Index | BMF | Premature greying | |

| 15 | Sister | Premature greying | ||

| 16 | Index | LD, PF | ||

| 17 | Index | BMF | ||

| 17 | Mother | Premature greying | ||

| 18 | Index | ND, SP, LP | PF, dental | |

| 18 | Sister | ND, SP, LP | PF | |

| 19 | Index | BMF | LP | CH, MC, low birth weight, scoliosis |

| 20 | Index | MDS | ||

| 21 | Index | ID | SP café au lait spot | MC, low birth weight |

| 22 | Index | BMF | LP | CH |

| 22 | Sister | CH | ||

| 22 | Father | BMF | ND, SP, LP | Hair loss, premature greying |

| 23 | Index | BMF | ND, SP, LP | |

| 23 | Brother | LP |

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BMF, bone marrow failure; CH, cerebellar hypoplasia; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FH, family history; ID, immune deficiency; LD, liver disease; LP, leukoplakia; MC, microcephaly; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; ND, nail dystrophy; PF, pulmonary fibrosis; SP, abnormal skin pigmentation; wbc, white blood cell count.

Variants of uncertain status

We have identified 6 variants which, with all the currently available data, remain of uncertain status (Figure 1; Table 1; families 13-18). One of the problems encountered in trying to assign pathogenic status to a variant is that the details of the patient’s family history are often limited. We have therefore classed a variant as having uncertain status if it does not cause LOF and the patient either has (1) no other family members with disease features (or their phenotype is unknown) or (2) family members with disease features but segregation of the variant is unknown.

This applies to 5 of the TERT variants that we have identified. In 1 of these, a boy with early onset DC (family 13), had inherited p.Arg381Cys from his asymptomatic father (Table 1), a variant that gave 66% wild-type activity in a TRAP assay (Figure 2B). In 4 other cases with previously unreported variants (p.Val119Met, p.Met773Thr, p.Val777Leu, and p.Tyr825Cys), the clinical presentation and family history is typical of patients with disease-causing TERT variants. These features include BMF, liver disease, pulmonary fibrosis, and/or apparent autosomal-dominant inheritance (Table 2). However, in each case, other family members are unavailable and segregation cannot be established. In addition, the TRAP data are either unavailable (which is the case in a diagnostic setting) or show >100% wild-type activity (Figure 2B). We note that an in vitro TRAP assay may reveal a variant has normal telomerase activity, yet it could still be pathogenic due to errors in recruitment or assembly. These variants therefore have to remain of uncertain status.

Family 18 is particularly interesting as a TERC variant (r.202T>G) is seen in a homozygous state in the index case and her affected sister (Figure 1). To our knowledge, this is the first report of a homozygous variant in TERC. The proband is a 58-year-old women with dental abnormalities and both her and her affected sister have pulmonary fibrosis and mucocutaneous features (Table 2). The TRAP assay revealed a telomerase activity of 92% wild-type (Figure 2B) which does not denote LOF. Although 3 additional family members have disease features, the segregation of the variant among these individuals, as well as unaffected siblings and parents, remains unknown. We therefore class this variant as status uncertain due to the limited information available from family members.

Variants that are bystanders

Somewhat surprisingly, we have identified 5 variants which we believe are likely to be bystanders (Figure 1; Table 1; families 11 and 19-22). We consider a heterozygous variant to be a bystander if it has been reported on the ExAC database. This is true of TERT variants p.Pro530Leu (identified in conjunction with the LOF variant in family 11) and p.Arg979Gln (identified in family 19). If a variant has been previously reported at a frequency of ∼1 in 100 000 it is unlikely to cause a rare disorder. The TERC variant in family 20 (r.93G>C), who presented with MDS at the age of 14 and was found to be heterozygous in both parents, is also present on the ExAC database.

The TERT variant identified in family 21 (p.Glu705Gln) is also likely to be a bystander because variants in a different disease gene have been identified in this patient, who presented with immune deficiency alongside a café au lait spot, low birth weight, and microcephaly. She stands out as her telomeres were above the 50th centile (Figure 2A), which suggested that telomere maintenance was not the cause of pathology. She was subsequently found to have compound heterozygous LOF variants in LIG4, which cause the immune-deficiency disorder ligase IV syndrome (LIG4 syndrome, OMIM 601837).

We have previously described family 22 with the TERT variant p.Phe1127Leu, which was shown to be inherited by the index case from her asymptomatic mother.16 The proband had a severe HHS-like phenotype (Table 2) and it was noted that her mother may be asymptomatic due to an extreme case of anticipation. However, functional analysis later showed the substitution gave ∼100% wild-type telomerase activity, suggesting it did not have a negative impact.38 Since this original report, the proband’s father, who is wild type for TERT, developed features of disease (Table 2). This TERT variant therefore turns out to be a bystander, as it is not present in the affected father.

Categorization of telomerase variants

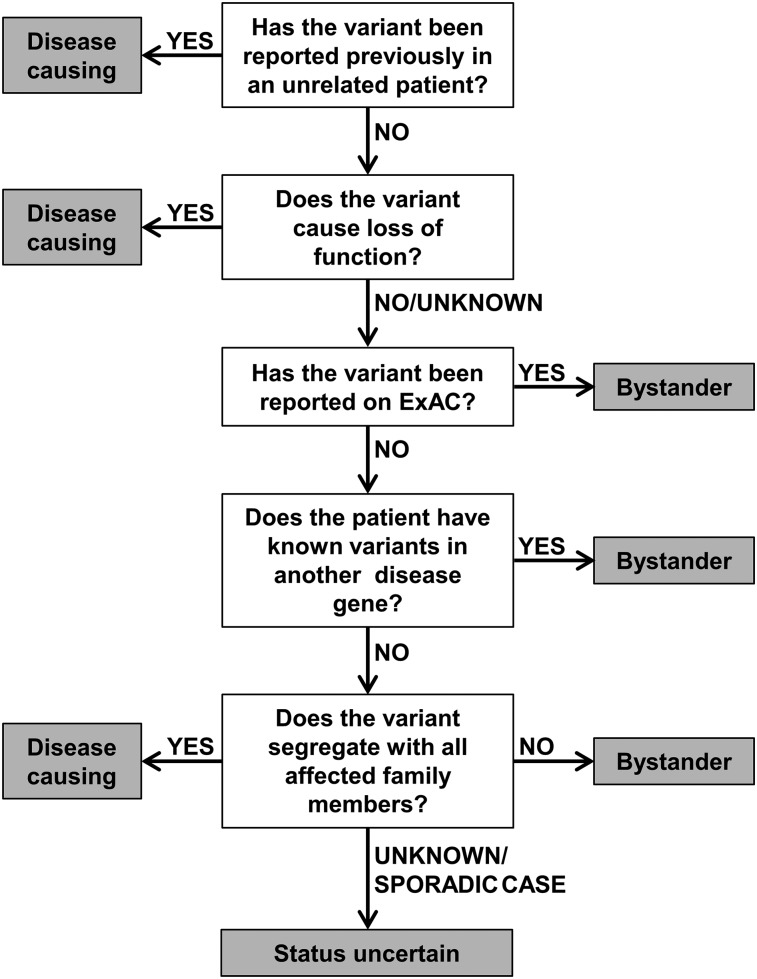

In order to aid the assignment of pathogenic status, we have established a diagnostic algorithm to characterize the likely impact of telomerase variants (Figure 3). This groups the variants into categories of (1) disease-causing, (2) status uncertain, and (3) bystander, as described in this article. The algorithm considers whether a variant has been reported previously in disease, the nature of the variant (ie, if it causes LOF), its frequency of the variant in a general population, the presence of variants in other known disease genes, and the family history of the patient (where available). The algorithm acknowledges that details of a patient’s family history are often incomplete and does not rely on TL to predict the impact of a variant. This is because short telomeres alongside a telomerase variant may not mean the variant is disease-causing.

Figure 3.

Diagnostic algorithm for the characterization of telomerase variants. Variants are considered disease-causing if they have been reported in other unrelated patients or cause LOF. Conversely, variants are considered bystanders if they appear on ExAC or if a different disease gene has been identified. Additionally, a variant is classed as a bystander if it does not segregate with all affected members of a family. If segregation of the variant is unknown (or if a patient is a sporadic case) and if TRAP activity is >5% or unknown, a variant should be considered as status uncertain.

Families with novel disease mechanisms: triallelic inheritance in the index case

The TERT variant p.Lys1050Asn identified in family 7, which shows intermediate telomerase activity in the TRAP assay (56%, Figure 2B), has been reported on the ExAC database in 10 of 114 130 alleles. However, in this family, it was found in a homozygous state in the index case and his sister, who both have BMF and nail dystrophy, with the index case additionally presenting with abnormal skin pigmentation, dental abnormalities, and renal failure (Figure 1; Tables 1-2). The family are Ashkenazi Jews and this variant may be enriched due to a founder effect in this population. Remarkably, the index case in this family also has the novel TERC variant r.205C>T which has low telomerase activity (4.7%, Figure 2B). However, his affected sister is wild type for TERC. Thus, the index case, who has a more severe clinical phenotype and shorter telomeres than his sister (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site), has both a homozygous TERT variant as well as a heterozygous TERC variant. His sister, with a less severe clinical phenotype, only has the homozygous TERT variant. The exome data from the proband was extensively analyzed and no other variants were identified in known disease genes or genes known to be involved in telomere biology. We therefore propose a triallelic model of inheritance in this index case.

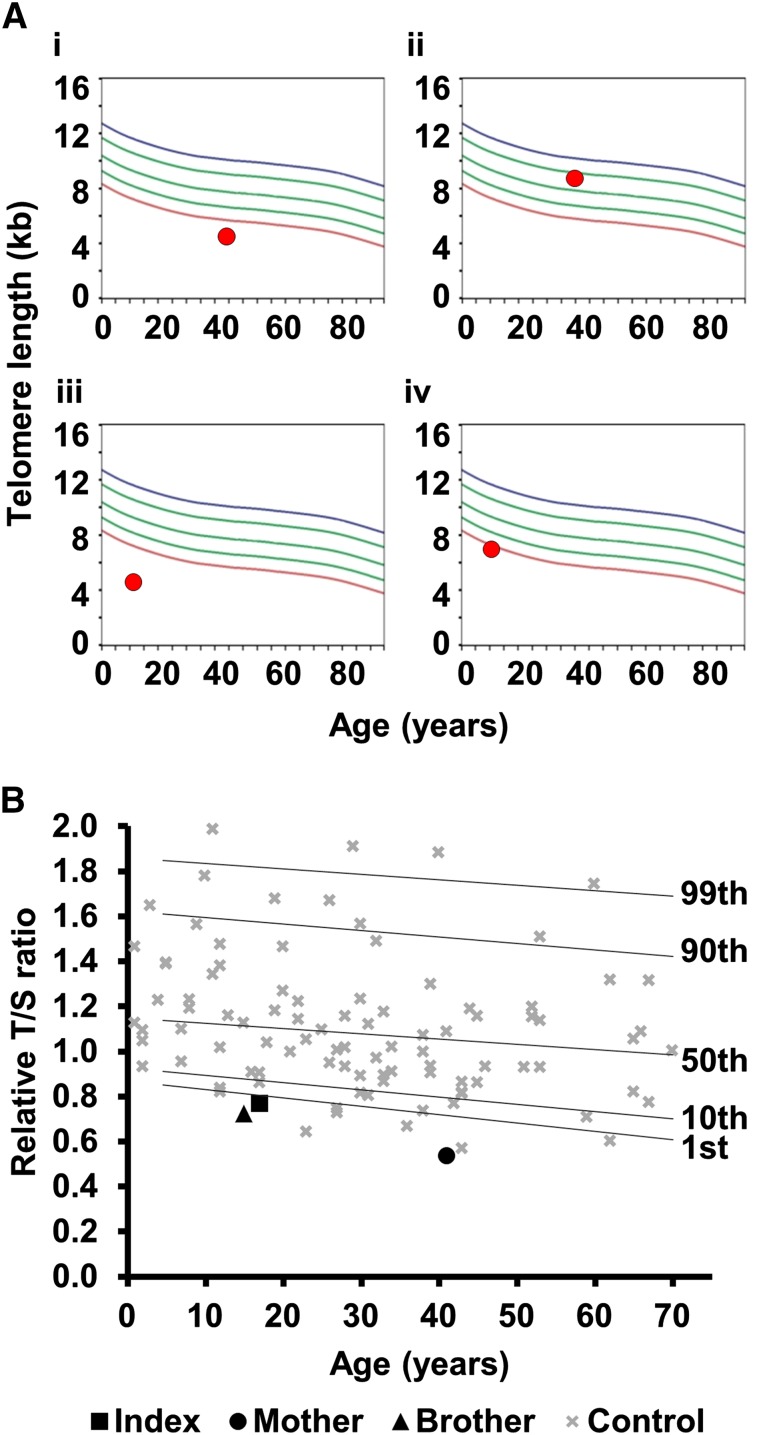

Disease phenotype in individuals arising from inherited short telomeres in presence of normal telomerase

In family 8, the proband has a severe HHS phenotype, with BMF, cerebellar hypoplasia, microcephaly, and ataxia (Table 2). He has the TERC variant r.448A>G, inherited from his asymptomatic father. This variant impacts on the ACA box of TERC and reduces telomerase activity to 2.2% of wild-type levels (Figure 2B). However, his sister, who also has microcephaly and cerebellar hypoplasia, is wild type for TERC. TLs in this family were measured by flow-FISH, showing that the father and both siblings had very short telomeres (Figure 4). Fifty-two genes linked to inherited BMF were sequenced in the proband (as part of a previous study28) and no novel variants were revealed. Although we cannot rule out the contribution of a variant in another gene, we propose that the inheritance of short telomeres, alongside the TERC variant, has caused the severe disease phenotype observed in the proband. His sister, on the other hand, presents with fewer disease features due to the inheritance of short telomeres through the germline while being wild type for TERC.

Figure 4.

Telomere lengths in families 8 and 23. (A) Lymphocyte telomere lengths in family 8 measured by flow-FISH. (i) Father of the index, asymptomatic with TERC variant r.448A>G; (ii) mother of the index, asymptomatic, wild type for TERC; (iii) index case with TERC variant r.448A>G; (iv) sister of the index, affected, wild type for TERC. Curved lines represent 99th, 90th, 50th, 10th, and first percentiles. (B) Telomere lengths of family 23 measured by MM-qPCR. Telomere lengths are expressed as a T:S ratio for the index case, his mother (heterozygous for TERT variant) and his brother (wild type for TERT). These are compared with 99 normal controls (as in Figure 2A). Percentiles for the normal controls are indicated. All samples were normalized to a reference.

In family 23, the index case manifests a full DC phenotype and has the heterozygous TERT variant, p.Arg381Gly. This variant has intermediate telomerase activity based on the TRAP assay (51%, Figure 2B). His brother is wild type for TERT but has leukoplakia. Exome sequencing in the proband failed to reveal any other likely disease-causing variants. As in family 8, it is likely that the inheritance of short telomeres alongside the TERT variant has caused more severe phenotype in the index case, whereas the younger brother has inherited short telomeres (Figure 4), but is wild type for TERT, leading to a milder phenotype.

We therefore propose that in these 2 families, the inheritance of short telomeres exacerbates the disease in the probands who harbor telomerase variants, consistent with previous observations of disease anticipation. However, we now also suggest that the inheritance of short telomeres alone is sufficient to cause the disease phenotypes observed in affected siblings, in the absence of a telomerase variant.

Discussion

To date, we are aware of 75 TERT and 49 TERC disease-associated variants, listed in the Telomerase Database (http://telomerase.asu.edu/) as well as other published sources.11 Here, we have reported on 26 telomerase variants (17 in TERT and 9 in TERC) in 23 different families. Reviewing each 1, we have found it helpful to place them into 1 of 3 different categories: (1) disease-causing, (2) status uncertain, and (3) bystander. In doing so, this study highlights the difficulties in assigning pathogenic status to telomerase variants. We have therefore established an algorithm, which we present here, that will help to objectively categorize telomerase variants. It considers 5 key factors: (1) the reoccurrence of a variant within the disease population, (2) the type of variant and its functional impact, (3) the frequency of the variant in a general population, (4) the presence of variants in other known disease genes, and (5) the family history of disease and segregation of the variant among affected individuals.

We believe that variants reported on the ExAC database are unlikely to be disease-causing in the heterozygous state because DC is a very rare disease. However, other disease phenotypes associated with telomerase variants are more common, notably idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis which has an estimated prevalence of between 14 and 42.7 in 100 000.39 We therefore suggest that if a TERT variant in a patient with pulmonary fibrosis appears on ExAC it should not be ruled out as a bystander without further investigation.

All of the patients reported in this series had short or very short telomeres, bar 1. On its own, therefore, the presence of short telomeres does not demonstrate that the telomerase variant identified is disease-causing. We considered variants that significantly reduced telomerase activity (<5% of wild type) were disease-causing. However, interpreting intermediate TRAP levels can be difficult because there is no designated “cutoff” describing a level of activity needed for normal telomerase function. Xin et al have grouped variants, giving TRAP scores between 20% and 100% of wild-type levels as within a normal range,38 whereas Zaug et al, using a direct telomerase assay, described 10% to 50% as “substantially reduced activity.”40 Surprisingly, these authors found that a significant number of disease-associated TERT variants showed normal telomerase activities in their direct assay. It is possible that alternative methods that directly measure telomerase processivity41 or telomerase recruitment42,43 would further help to characterize these variants.

Remarkably, we have identified 3 families that appear to display novel mechanisms in the inheritance of telomere disorders. In 1 family (family 7), we describe an affected case with a severe phenotype associated with mutations in 2 different telomerase genes (homozygous variant in TERT and heterozygous variant in TERC). This individual therefore has 3 mutant telomerase alleles, representing a triallelic disease model. It is notable that studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have demonstrated a similar effect called “additive haploinsufficiency.” Diploid organisms with heterozygous deletions in 2 telomerase genes were shown to have an enhanced phenotype (telomere shortening and an accelerated onset of senescence in haploid progeny that inherit a deletion in a single telomerase gene) compared with strains carrying only 1 mutation.44,45 In human disease, a similar triallelic phenomenon has been documented previously in the heterogeneous disorder Bardet-Biedl syndrome.46

In 2 other families (families 8 and 23), we find that the index cases have a more severe phenotype because of the inheritance of short telomeres from a parent in association with a telomerase variant whereas a corresponding affected sibling has mild disease due to the inheritance of short telomeres but with normal telomerase. This is the first observation in humans of the generation of a clinical phenotype due solely to the inheritance of short telomeres from a parent, although this phenomenon has been documented previously in mice.47,48 Although this represents an epigenetic-like mechanism of inheritance, it is not dissimilar to the effect that short telomeres have in hastening disease in people who are heterozygous for telomerase mutations, which is thought to be the mechanism underlying the observed disease anticipation in these disorders. It has also been proposed that this atypical, epigenetic-like mechanism of TL inheritance may account for a significant proportion of the heritability of TL in the general population.49

In summary, this study highlights the complexity in categorizing telomerase variants, documents new mechanisms involved in generating human telomeropathies, and demonstrates that thorough investigation is necessary to assess the pathogenic contribution of newly identified telomerase variants. This will become increasingly important and difficult as exome-based diagnostic reports are generated without reference to the many nuances that may be encountered.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Charles Mein, Anna Terry, and Monika Bozek of the Barts and The London Genome Centre for their help with DNA sequencing; Vincent Plagnol for variant calling of the exome data; and all of the patients and clinicians who entered samples into this study.

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC; UK) and Children with Cancer.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: L.C.C. performed research and wrote the paper; A.J.W., S.C., A.J.Y.V.L., T.L., R.K., and H. Tummala performed research; J.d.l.F., M.M., H. Toriello, and H. Tamary provided clinical samples; and T.J.V. and I.D. designed the research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Thomas J. Vulliamy, Centre for Genomics and Child Health, Blizard Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, 4 Newark St, London E1 2AT, United Kingdom; e-mail: t.vulliamy@qmul.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Calado R, Young N. Telomeres in disease. F1000 Med Rep. 2012;4:8. doi: 10.3410/M4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armanios M, Blackburn EH. The telomere syndromes. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(10):693–704. doi: 10.1038/nrg3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dokal I. Dyskeratosis congenita. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:480–486. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knight SW, Heiss NS, Vulliamy TJ, et al. Unexplained aplastic anaemia, immunodeficiency, and cerebellar hypoplasia (Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome) due to mutations in the dyskeratosis congenita gene, DKC1. Br J Haematol. 1999;107(2):335–339. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alter BP, Baerlocher GM, Savage SA, et al. Very short telomere length by flow fluorescence in situ hybridization identifies patients with dyskeratosis congenita. Blood. 2007;110(5):1439–1447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-075598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savage SA, Alter BP. Dyskeratosis congenita. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23(2):215–231. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harley CB, Futcher AB, Greider CW. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature. 1990;345(6274):458–460. doi: 10.1038/345458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allsopp RC, Vaziri H, Patterson C, et al. Telomere length predicts replicative capacity of human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(21):10114–10118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shay JW, Bacchetti S. A survey of telomerase activity in human cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33(5):787–791. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Lange T. Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev. 2005;19(18):2100–2110. doi: 10.1101/gad.1346005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dokal I, Vulliamy T, Mason P, Bessler M. Clinical utility gene card for: dyskeratosis congenita - update 2015. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(4) doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vulliamy T, Marrone A, Goldman F, et al. The RNA component of telomerase is mutated in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Nature. 2001;413(6854):432–435. doi: 10.1038/35096585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamaguchi H, Baerlocher GM, Lansdorp PM, et al. Mutations of the human telomerase RNA gene (TERC) in aplastic anemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2003;102(3):916–918. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armanios MY, Chen JJ, Cogan JD, et al. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(13):1317–1326. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calado RT, Regal JA, Hills M, et al. Constitutional hypomorphic telomerase mutations in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(4):1187–1192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807057106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vulliamy TJ, Walne A, Baskaradas A, Mason PJ, Marrone A, Dokal I. Mutations in the reverse transcriptase component of telomerase (TERT) in patients with bone marrow failure. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2005;34(3):257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armanios M, Chen JL, Chang YP, et al. Haploinsufficiency of telomerase reverse transcriptase leads to anticipation in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(44):15960–15964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508124102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaguchi H, Calado RT, Ly H, et al. Mutations in TERT, the gene for telomerase reverse transcriptase, in aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(14):1413–1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsakiri KD, Cronkhite JT, Kuan PJ, et al. Adult-onset pulmonary fibrosis caused by mutations in telomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(18):7552–7557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701009104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calado RT, Brudno J, Mehta P, et al. Constitutional telomerase mutations are genetic risk factors for cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;53(5):1600–1607. doi: 10.1002/hep.24173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirwan M, Vulliamy T, Marrone A, et al. Defining the pathogenic role of telomerase mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(11):1567–1573. doi: 10.1002/humu.21115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vulliamy T, Marrone A, Szydlo R, Walne A, Mason PJ, Dokal I. Disease anticipation is associated with progressive telomere shortening in families with dyskeratosis congenita due to mutations in TERC. Nat Genet. 2004;36(5):447–449. doi: 10.1038/ng1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vulliamy TJ, Marrone A, Knight SW, Walne A, Mason PJ, Dokal I. Mutations in dyskeratosis congenita: their impact on telomere length and the diversity of clinical presentation. Blood. 2006;107(7):2680–2685. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tummala H, Kirwan M, Walne AJ, et al. ERCC6L2 mutations link a distinct bone-marrow-failure syndrome to DNA repair and mitochondrial function. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94(2):246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cawthon RM. Telomere length measurement by a novel monochrome multiplex quantitative PCR method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(3):e21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walne AJ, Dokal A, Plagnol V, et al. Exome sequencing identifies MPL as a causative gene in familial aplastic anemia. Haematologica. 2012;97(4):524–528. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.052787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walne AJ, Vulliamy T, Kirwan M, Plagnol V, Dokal I. Constitutional mutations in RTEL1 cause severe dyskeratosis congenita. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92(3):448–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collopy LC, Walne AJ, Vulliamy TJ, Dokal IS. Targeted resequencing of 52 bone marrow failure genes in patients with aplastic anemia reveals an increased frequency of novel variants of unknown significance only in SLX4. Haematologica. 2014;99(7):e109–e111. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.105320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basel-Vanagaite L, Dokal I, Tamary H, et al. Expanding the clinical phenotype of autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita caused by TERT mutations. Haematologica. 2008;93(6):943–944. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diaz de Leon A, Cronkhite JT, Katzenstein AL, et al. Telomere lengths, pulmonary fibrosis and telomerase (TERT) mutations. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(5):e10680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernandez BA, Fox G, Bhatia R, et al. A Newfoundland cohort of familial and sporadic idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients: clinical and genetic features. Respir Res. 2012;13(64):64–74. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-13-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Snow BE, Hande MP, et al. The telomerase reverse transcriptase is limiting and necessary for telomerase function in vivo. Curr Biol. 2000;10(22):1459–1462. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00805-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Kha H, Ungrin M, Robinson MO, Harrington L. Preferential maintenance of critically short telomeres in mammalian cells heterozygous for mTert. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(6):3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062549199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erdmann N, Liu Y, Harrington L. Distinct dosage requirements for the maintenance of long and short telomeres in mTert heterozygous mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(16):6080–6085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401580101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacArthur DG, Balasubramanian S, Frankish A, et al. 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A systematic survey of loss-of-function variants in human protein-coding genes. Science. 2012;335(6070):823–828. doi: 10.1126/science.1215040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marrone A, Walne A, Tamary H, et al. Telomerase reverse-transcriptase homozygous mutations in autosomal recessive dyskeratosis congenita and Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome. Blood. 2007;110(13):4198–4205. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-062851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Du HY, Pumbo E, Manley P, et al. Complex inheritance pattern of dyskeratosis congenita in two families with 2 different mutations in the telomerase reverse transcriptase gene. Blood. 2008;111(3):1128–1130. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-120907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xin ZT, Beauchamp AD, Calado RT, et al. Functional characterization of natural telomerase mutations found in patients with hematologic disorders. Blood. 2007;109(2):524–532. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-035089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raghu G, Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Bradford WZ, Oster G. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(7):810–816. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-163OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zaug AJ, Crary SM, Jesse Fioravanti M, Campbell K, Cech TR. Many disease-associated variants of hTERT retain high telomerase enzymatic activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(19):8969–8978. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhong FL, Batista LF, Freund A, Pech MF, Venteicher AS, Artandi SE. TPP1 OB-fold domain controls telomere maintenance by recruiting telomerase to chromosome ends. Cell. 2012;150(3):481–494. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nandakumar J, Bell CF, Weidenfeld I, Zaug AJ, Leinwand LA, Cech TR. The TEL patch of telomere protein TPP1 mediates telomerase recruitment and processivity. Nature. 2012;492(7428):285–289. doi: 10.1038/nature11648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vulliamy TJ, Kirwan MJ, Beswick R, et al. Differences in disease severity but similar telomere lengths in genetic subgroups of patients with telomerase and shelterin mutations. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9):e24383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lendvay TS, Morris DK, Sah J, Balasubramanian B, Lundblad V. Senescence mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with a defect in telomere replication identify three additional EST genes. Genetics. 1996;144(4):1399–1412. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hughes TR, Evans SK, Weilbaecher RG, Lundblad V. The Est3 protein is a subunit of yeast telomerase. Curr Biol. 2000;10(13):809–812. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00562-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katsanis N, Ansley SJ, Badano JL, et al. Triallelic inheritance in Bardet-Biedl syndrome, a Mendelian recessive disorder. Science. 2001;293(5538):2256–2259. doi: 10.1126/science.1063525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hao LY, Armanios M, Strong MA, et al. Short telomeres, even in the presence of telomerase, limit tissue renewal capacity. Cell. 2005;123(6):1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Armanios M, Alder JK, Parry EM, Karim B, Strong MA, Greider CW. Short telomeres are sufficient to cause the degenerative defects associated with aging. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85(6):823–832. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Meyer T, Vandepitte K, Denil S, De Buyzere ML, Rietzschel ER, Bekaert S. A non-genetic, epigenetic-like mechanism of telomere length inheritance? Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22(1):10–11. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]