Abstract

This study examines depression-related chatter on Twitter to glean insight into social networking about mental health. We assessed themes of a random sample (n=2,000) of depression-related tweets (sent 4-11 to 5-4-14). Tweets were coded for expression of DSM-5 symptoms for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Supportive or helpful tweets about depression was the most common theme (n=787, 40%), closely followed by disclosing feelings of depression (n=625; 32%). Two-thirds of tweets revealed one or more symptoms for the diagnosis of MDD and/or communicated thoughts or ideas that were consistent with struggles with depression after accounting for tweets that mentioned depression trivially. Health professionals can use our findings to tailor and target prevention and awareness messages to those Twitter users in need.

Keywords: Social media, depression

1. Introduction

The use of social media platforms has steadily risen over the past decade, and recent surveys estimate that 90% of online adolescents and young adults in the United States use some kind of social networking site (Duggan & Smith, 2013). One of the most popular social networking sites is Twitter with 19% of online American adults using its platform (Duggan & Smith, 2013). In fact, 35% of internet users of ages 18-29 use Twitter, and American teenagers named it the “most important social media network” in a 2013 market research survey (Brenner, 2013; Edwards, 2013). Additionally, latest data from a 2014 survey from the Pew Research Center found that 23% of online adults currently use Twitter, which is a 5% increase from 2013 (Duggan, Ellison, Lampe, Lenhart, & Madden, 2015). Twitter is a microblogging platform where users create short updates that are less than 140 characters. These “tweets” are then viewed by a network of “followers” that choose to follow the user’s account (Marwick, 2011).

Because of the ease with which Twitter allows users to connect with a large audience of acquaintances and strangers, its popularity has grown, especially with teens and young adults (Brenner, 2013; De Cristofaro, Soriente, Tsudik, & Williams, 2012). In fact, Twitter contrasts with other popular social media platforms like Facebook, because Twitter users tend to keep their posts public while Facebook profiles often use privacy settings. Adults between the ages of 55-64 are now the fastest growing demographic on Facebook (Tappin, 2014) and, consequently, it is considered by many teens to have a prominent adult presence (Madden et al., 2013). In contrast, most of the Twitter users are young (66% are 25 years old and under) (Bennett, 2014; De Cristofaro et al., 2012). In terms of the demographic specifics among teen Twitter users, Twitter is more popular among girls versus boys (37% versus 30%). Additionally, African American teens use Twitter to a higher degree than Caucasian counterparts (45% versus 31%) (Lenhart et al., 2015). Given that there is less interaction or oversight from older adults/parents, in general on Twitter, young Twitter users can feel free to openly communicate with friends and acquaintances about virtually anything, even topics as traditionally private as mental illness.

Depression tends to be a stigmatized condition (Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein, & Zivin, 2009) and many people consider the struggle of such symptoms to be “private matters” and/or choose not to seek treatment because they do not want to be labeled as a psychiatric patient (Bland, Newman, & Orn, 1997; Dew, Dunn, Bromet, & Schulberg, 1988; Sirey et al., 2001). Moreover, self-harm, defined as intentional self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of type of motive or the extent of suicidal intent, is a grave public health problem among young people (Hawton, Saunders, & O’Connor, 2012). Thoughts about self-harm are also a risk factor for suicide and are strongly associated with mental illnesses, especially Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (Evans, Hawton, & Rodham, 2004; Kessler, Berglund, Borges, Nock, & Wang, 2005; Pfaff & Almeida, 2004).

Several studies have examined references to depression, self-harm, and suicidality on social media in an effort to better understand the information being shared and discussed, however the research on this topic is still in its infancy. For instance, existing research has identified that posts about stress and depressive symptoms are common on Facebook profiles (Egan & Moreno, 2011; Moreno et al., 2011). In addition, an individual’s social media posts about feeling depressed corresponded well with the depression symptoms they self-reported on a depression screening tool (Moreno et al., 2012). Studies focused on depression-related tweets have been relatively few in number but nonetheless signal that such risk factors as suicidality, self-harm, and depression are posted on Twitter. For instance, De Choudhury et al. (2013) studied the tweets of individuals who had been diagnosed with MDD according to self-report responses using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Based on their retrospective study evaluating tweets for one year prior to the reported onset of MDD, the researchers detected lowered social activity, greater negative emotion, high self-attentional focus, increased relational and medicinal concerns, and heightened religious thoughts among individuals who scored positively for depression when compared against individuals who scored negatively for depression using ratings from the CES-D. In a related study, researchers examined the keyword “depression” on Twitter for two months in 2009 and yielded 20,000 tweets; the researchers found initial evidence that individuals tweet about their depression and even disclosed updates about their mental health treatment on Twitter (Park, Cha, & Cha, 2012). Likewise, a case study of tweets posted by a Twitter user prior to committing suicide found that suggestions of suicide were noted in the individual’s tweets immediately prior to the suicide occurring (Gunn & Lester, 2012). Another related study found associations between clusters of at-risk suicide Twitter conversations and increased prevalence of geographic-specific suicide rates reported in traditional data sources (Jashinsky et al., 2015). Lastly, a study of Tweeters in Japan found that self-reported lifetime suicide attempts were associated with tweets expressing suicidality (Sueki, 2015).

There is still much to learn about the content of depression-related tweets. Symptoms of depression have been observed in Facebook posts (Egan & Moreno, 2011; Moreno et al., 2011); however, it is unknown if in some cases, clinical symptoms of depression can be identified in tweets. At the other extreme, while there is some indication that Tweeters provide encouragement to individuals with depression (Park, Cha, & Cha, 2012), the extent of supportive tweets (i.e., educational and prevention messages) about depression is likewise unclear even though it is quite possible that Tweeters seek out or post supportive comments or advice about depression on Twitter. Furthermore, as stated in a recent editorial published in this journal, the need for researchers to develop a deeper understanding of this type of cyberbehavior has never been more timely or more important (Guitton, 2014). In response, the present study answers the following research questions: What are the most common themes of depression-related chatter on Twitter and how well do some tweets correspond with clinical symptoms of depression? In addition, what are the demographic characteristics of Twitter users posting this type of content? In addressing these research aims, our exploratory study gleans insight into the conversations and social networking that is occurring about depression on Twitter, and who is participating in these conversations, which offers a unique contribution to an emerging field of research.

2. Methods

The Twitter data in the current study is public. The study protocol was approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board.

2.1.Tweets related to depression

Tweets about depression were collected by Simply Measured, a company that specializes in social media measurement and analytics (Simply Measured, 2014). Simply Measured has access to the Twitter “firehose” (or full volume of tweets) via Gnip, a licensed company that can retrieve the full Twitter data stream.

All tweets in the English language that contained at least either “depressed”, “#depressed”, “depression,” or “#depression” were collected between April 11 and May 4, 2014. We scanned a random sample of the tweets to identify common phrases that included our keywords of interest but were not about mental health. In SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), we used the index function, which searches a character expression (in this case, the text of the tweet) for a specific string of characters, to locate and remove such tweets from our sample. We removed tweets that included the following terms, regardless of capitalization: “Great Depression”, “economic depression”, “during the depression”, “depression era”, “tropical depression”, and “depressed real estate.

The popularity and influence of the Tweeters was described using the distribution of followers and Klout Scores. While number of followers is a measure of popularity, Klout Score is a measure of influence. Klout Scores range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating higher influence. Klout Score is calculated based on an algorithm that considers over 400 signals from eight different online networks. Examples of signals include the amount of retweets a person generates in relation to the amount of tweets shared and the amount of engagement a user drives from unique individuals (e.g., lots of retweets from different individuals as opposed to lots of retweets from one person) (Klout Inc., 2014).

2.2.Themes

Using the SAS surveyselect procedure, we selected a simple random sample of 2,000 tweets (that were not direct @replies) from the total volume of depression-related tweets. Two members of the research team, each with graduate level degrees (i.e. Ph.D. and M.P.H) and more than 10 years of experience in mental health research, scanned approximately 300 random tweets in order to determine their most common themes and generate a codebook. We defined themes as topics that occur and reoccur (Ryan & Bernard, 2003). Tweets were coded for presence of the following themes: 1) Tweeter discloses feelings of depression; 2) Tweet is a supportive or helpful message about depression; 3) Tweeter discloses feeling school or work-related pressures related to depression; 4) Tweeter engages in substance use to deal with depression; and 5) Tweeter discloses self-harm or suicidal thoughts. Tweets could be assigned as many themes as were pertinent. For tweets where the user indicated that he or she was feeling depressed, those that appeared trivial (i.e., not concerning) were identified. These were tweets where the depression terms were used casually or in a humorous manner or referenced depression caused by trivial things, such as being depressed after finishing a good book, seeing a concert, or watching a sad movie.

In addition, we ascertained the source of the tweet by viewing the Tweeter’s profile picture and studying their Twitter handle name. The source was then coded into one of the three following categories: clinician/therapist, health-focused handle (e.g., health/government organization, handle focused on healthy lifestyle, etc.), or regular person or other (handle did not fall into the above categories).

Using this codebook, the 2,000 randomly sampled tweets were coded in teams of two trained student research interns who coded the tweets together, discussing each tweet and coming to an agreement on the final assigned codes. A sample of 150 tweets was also coded by a senior team member (Ph.D. clinician) with extensive mental health research experience. Inter-coder reliability for each theme was as follows: 1) Tweeter discloses feelings of depression: percent agreement 85%, kappa 0.67; 2) Tweet is a supportive or helpful message about depression: percent agreement 85%, kappa 0.70; 3) Tweeter discloses feeling school or work-related pressures related to depression: percent agreement 98%, kappa 0.72; 4) Tweeter engages in substance use to deal with depression: percent agreement 100%, kappa 1.0; 5) Tweeter discloses self-harm or suicidal thoughts: percent agreement 98%, kappa 0.56; 6) trivial disclosures of depression: percent agreement 90%, kappa 0.70; 7) source of Tweet: percent agreement 91%, kappa 0.51. Because both prevalence of and kappa for diminished ability to think/concentrate were low, we chose not to report on this code.

2.3.Presence of depression symptoms

Tweets where the Tweeter expressed feelings of depression, and were not deemed trivial, were further coded to identify whether symptoms of depression were also expressed. Symptoms of MDD, according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), included depressed mood or irritable most of the day, nearly every day, decreased interest or pleasure in most activities, significant weight change or change in appetite, change in sleep, psychomotor agitation or retardation, fatigue or loss of energy, guilt or worthlessness, diminished ability to think or concentrate or indecisiveness, and self-harm/suicidality (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). The research team also coded tweets that disclosed thoughts about self-harm as endorsing a symptom of depression. Because most Tweeters did not specify the length of time that they had been experiencing a symptom, we did not use the criteria of “nearly every day” for the symptoms. For example, if the Tweeter mentioned feeling decreased interest or pleasure in most activities, we coded this Tweet as endorsing a symptom of depression even though it was not clear if the Tweeter had been experiencing this symptom “nearly every day”. However, when only general feelings of depression were expressed (i.e., depressed mood or irritability), we did take the length of the depressed mood into consideration in order to distinguish the depression-related tweets that described a chronic or long-term struggle with depression. Specifically, we differentiated between tweets that provided no information about a length of time for the depressed mood (e.g. “I’m depressed”) from those glethat indicated that the Tweeter was feeling depressed for an extended length of time such as “I’m tired of being depressed all the time.” Psychomotor agitation or retardation must be objective (i.e., observable by others) and was therefore not coded.

Two team members with graduate degrees (Ph.D. and M.P.H.) and expertise in mental health research separately coded each of the tweets for symptoms of MDD symptomatology and/or self-harm. First the presence of any symptom was coded, with good agreement (percent agreement 87%; kappa 0.65). The team members then discussed the remaining tweets where there was disagreement to come to a consensus on whether any symptoms were present. Then the team members further reviewed the tweets where at least one symptom was present in order to code the specific symptoms present in the tweets. Inter-coder agreement for each symptom was as follows: 1) depressed mood or irritable: percent agreement 82%, kappa 0.62; 2) decreased interest or pleasure in most activities: percent agreement 97%, kappa 0.65; 3) significant weight change or change in appetite: percent agreement 100%, kappa 1.0; 4) change in sleep: percent agreement 98%, kappa 0.76; 5) fatigue or loss of energy: percent agreement 98%, kappa 0.83; , 6) guilt or worthlessness: percent agreement 89%, kappa 0.69; 7) self-harm: percent agreement 97%, kappa 0.73; 8) suicidality: percent agreement 98%, kappa 0.89. ; agreement was good (median percent agreement across specific symptoms 97%, range 82% to 100%; median kappa 0.71, range 0.32 to 1.0). We chose not to report on diminished ability to think/concentrate in our results because both the prevalence of and kappa for this symptom were low. Any disagreements were then discussed in detail by the two researchers to determine whether the symptom was expressed in the tweet and a consensus reached.

2.4.Demographic characteristics

Demographics Pro was used to infer the demographic characteristics of the individuals who disclosed feeling depressed in the tweets that were examined in the present study (Demographics Pro for Twitter, 2014). The demographic characteristics examined include: age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, income, occupation, and location of the Tweeter. In order to assess for patterns in Twitter interests the most likely Twitter handles that are being followed by the Tweeters were also provided.

Demographics Pro uses a series of proprietary algorithms to estimate or infer likely demographic characteristics of Twitter handles based on Twitter behavior/usage. Their predictions rely on multiple data signals from networks (signals imparted by the nature and strength of ties between individuals on Twitter), consumption (consumption of information on Twitter revealed by accounts followed and real-world consumption revealed by Twitter usage), and language (words and phrased used in tweets and bios).

Demographics Pro has used their methodology to profile some 300 million Twitter users to date and requires confidence of 95% or above to make an estimate of a single demographic characteristic. For example, if 10,000 predictions are made, 9500 would need to be correct in order to accept the methodology used to make the prediction. The success of the Demographics Pro analytic predictions relies on the relatively low covariance of multiple amplified signals. Iterative evaluation testing the methodologies on training sets of established samples of Twitter users with verified demographics allows the calibration of balance between depth of coverage (the number of demographic predictions made) and required accuracy. The size of these established samples of Twitter users with verified demographics varies from 10,000 to 200,000 people depending on the specific demographic characteristic to be inferred.

For comparison purposes, inferred demographic characteristics across a sample of 20,000 randomly selected English-language Twitter users in the U.S. and Canada were also provided by Demographics Pro. We used Pearson chi square tests to compare the inferred characteristics of Tweeters from our sample who expressed feelings of depression versus the typical Twitter user. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

From April 11 to May 4, 2014, approximately 12,000,000,000 tweets were posted on Twitter (Simply Measured, 2014) and of this full stream of Twitter data, a total of 1,562,941 depression- related tweets were collected using our keywords of interest. The median number of followers of the tweets was 335 (inter-quartile range 137 – 825) and the median Klout score (or measure of influence) was 39.4 (inter-quartile range 30.5 – 44.2).

3.1.Themes

The 2,000 randomly sampled tweets had similar follower and Klout distribution as the full sample (follower’s median 335, inter-quartile range 139 – 821; Klout score median 38.4, inter-quartile range 29.8 – 43.9). Of the 2,000 randomly sampled tweets, 22 (1%) were not about depression in humans and were thus excluded from qualitative analysis. Of the 1,978 tweets that were about depression, 97% (n=1,910) were from unique Twitter handles.

Themes identified in the 1,978 randomly sampled tweets are presented in Table 1. Supportive or helpful tweets about depression was the most common theme (n=787, 40%) and included such messages as how to prevent depression, supportive or inspirational quotes for individuals struggling with depression, and how to help loved ones who are depressed.

Table 1.

Depression-related tweets (n=1,978 or 99% of 2,000)

| Themes | N (%) | Example Tweets |

|---|---|---|

| Supportive or helpful tweets about depression |

787 (40%) | * Depressed? We can Help! Bit.ly/1mjUTr7 #depression #mentalhealth #therapy * Exercise has been scientifically proven to treat depression just as well as taking medication would--and it’s much more natural! * Telling someone with depression to “get over it” is like telling someone with a broken leg to “walk it off” |

| Disclosure of depression | 625 (32%) | * Sometimes I become very depressed very quickly and it’s hard for me to pull out. Makes me feel broken at those times. * I’m so depressed nowadays I don’t remember what being happy feels like. * Depressed & alone |

| School or work-related pressures |

54 (3%) | * Too much homework has a negative impact on the GPA of High School students. Feeling overworked in school also causes depression. * school stresses me out that’s where all anger come from depression tears etc! * I blame school for my anxiety and depression. |

| Substance use and depression | 26 (1%) | * I feel myself getting depressed..excuse me if I wanna get drunk by myself. * Marijuana is one of the most highly effective ways to relieve depression and anxiety. * Party Drug may be a new remedy for serious depression… http://fb.me/1bGaKHvTe |

| Self-harm or suicidal thoughts | 21 (1%) | * Can’t wait to go away and fend for myself in the real world and drive myself further into depression and suicide. * Some days I just wanna die because I’m so depressed… * I’ll never understand people who joke about depression and self harm. |

Nearly 1/3 of the tweets were coded by our research team as being from individuals who disclosed feeling depressed (n=625, 32%). All of the tweets expressing feelings of depression were from unique Twitter handles. The other themes identified were much less common. School or work-related pressures were mentioned in 3% of the tweets (n=54) and substance use in the context of feeling depressed was found in 1% of the tweets (n=26).

3.2. Source of tweets

Most of the tweets (n=1,806, 92%) were from ordinary people or other Twitter accounts that did not fall into the above categories. Only 6% (n=112) of the tweets were from health focused handles such as health or government organizations or handles promoting healthy lifestyles (e.g., Doctor’s Nutrition @drsnutritionetx, Natural Health @naturalhealth92). In addition, only 3% (n=60) were from clinicians or therapists.

3.3.Symptoms of depression conveyed in tweets

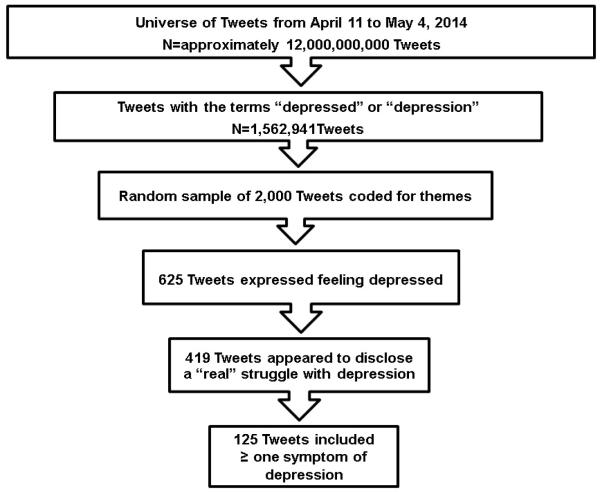

From the 625 tweets that disclosed feelings of depression, we identified 419 tweets where the Tweeter reported struggles that were consistent with depression (versus using “depression” or “depressed” in a trivial and/or humorous way; n= 206). The 419 tweets were further coded for the presence of one or more DSM-5 symptom(s) of MDD or indications of self-harm.

Of the 419 tweets, we identified 125 (30%) that included ≥ 1 symptom of MDD or self-harm. A flowchart of our study is provided in Figure 1 and examples of such tweets that included ≥ 1 symptom of MDD or self-harm are provided in Table 2. The most common DSM-5 symptoms of MDD that were disclosed within a tweet were feeling depressed mood or irritable (n=73/125, 58%) and guilt or worthlessness (n=30/125, 24%). MDD symptoms that were endorsed less frequently (<10%) included self-harm (n=10/125, 8%), contemplating suicide or expressing a desire for death (n=10/125, 8%), decreased interest or pleasure in most activities (n=9/125, 7%), fatigue or loss of energy (n=9/125, 7%), change in sleep (n=8/125, 6%), and significant weight change or change in appetite (n=1/125, <1%).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of tweets related to depression

Table 2.

Presence of symptoms of Major Depressive Disorder within the tweets (n=419)a

| N (%) | Example Tweets | |

|---|---|---|

| ------------------------------------------------ Symptoms of Major Depressive Disorder (n= 125, 30%) b ------------------------------------------------ | ||

| Depressed mood or irritable most of the day |

73/125 (58%) | * Most of the time I suffer from depression & stress. * I’m just so fuckin’ depressed, I just can’t seem to get out this slump. * Why am I depressed and sad 24\7 #Done |

| Guilt or worthlessness | 30/125 (24%) | * I’m depressed as fuck and I blame myself. * All my frendz hate me :/ #depressed #emo * I randomly get in the most shittiest depressed moods that make me hate every aspect about myself. |

| Contemplating suicide or desires death c |

10/125 (8%) | * I’m so depressed, I just wanna hurt myself. I just wanna close my eyes forever. I just wanna disappear. * I wake up every morning depressed and suicidal. * I keep reading that working out helps with depression, I literally work out everyday and everyday I still want to stop existing so now what. |

| Self-harm c | 10/125 (8%) | * Whenever I’m depressed, I like to cut myself * Nights were u feel so fucking depressed. Overthinks everything, decides to cut, and regret it after. * I’m not attention seeking but for every rt this gets I will not cut for a day. |

| -------------------------------------------------------------- No symptom specified (n= 294, 70%) -------------------------------------------------------------- | ||

| Feelings of depression, but no specific symptom identified |

* Depression sucks. That is all. * Soo depressed … ugh… * Feeling really depressed tonight. :( |

|

Excludes 206 tweets that appeared to use the terms casually or in a humorous manner, or referenced depression caused by trivial things.

MDD symptoms that were endorsed at a low frequency (< 10% ) include decreased interest or pleasure in most activities, significant weight change or change in appetite, change in sleep, psychomotor agitation or retardation, fatigue/loss of energy, and diminished ability to think or concentrate.

Even though suicidality/desires death and self-harm were endorsed at a low frequency (< 10%), example tweets are provided given their seriousness.

3.4.Demographics of Twitter users

Tweets where individuals expressed feelings of depression (and were not deemed trivial) was a popular theme of the tweets in our random sample and given the potential clinical implications associated with these social media messages, our research team had interest in characterizing the demographic characteristics of these individuals. Accordingly, Table 3 presents the inferred characteristics of Twitter users who tweeted about feeling depressed (n=419) compared to the inferred demographics of a random sample of 20,000 Tweeters in the US and Canada. Those tweeting about feeling depressed tended to be ≤25 years old (94%), which is similar to the typical Twitter user (94% ≤25 years old), but the distribution of ages under the age of 25 appeared to differ between the two groups (see Table 3). The vast majority of individuals who tweeted about feeling depressed were girls/women (77%) in comparison to the typical Twitter user (58%).

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of Tweeters

| Typical Twitter handle | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disclosed depression (n= 419 Twitter handles)a |

(n = 20,000 Twitter handles)b |

p | |

| Age, years | |||

| ≤16 | 22% | 16% | <.0001 |

| 17-19 | 55% | 67% | |

| 20-24 | 17% | 11% | |

| 25-29 | 2% | 3% | |

| 30-39 | 2% | 2% | |

| ≥40 | 2% | 1% | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 24% | 42% | <.0001 |

| Female | 77% | 58% | |

| Race (U.S. only) | |||

| Caucasian | 52% | 64% | <.0001 |

| African American | 35% | 24% | |

| Hispanic | 13% | 11% | |

| Asian | 0% | 1% | |

| Income | |||

| < $10,000 | 55% | 38% | <.0001 |

| $10,000-19,999 | 31% | 43% | |

| $20,000-29,999 | 9% | 9% | |

| $30,000-39,999 | 3% | 4% | |

| $40,000-49,999 | 1% | 3% | |

| ≥ $50,000 | 1% | 2% | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 86% | 74% | <.0001 |

| Married | 14% | 27% | |

| Top location | |||

| United States | 75% | 95% | <.0001 |

| United Kingdom | 9% | 0% | |

| Canada | 3% | 5% | |

| Other | 13% | 0% | |

| Following on Twitter | |||

| Miley Cyrus | 28% | 12% | <.0001 |

| Justin Bieber | 23% | 6% | <.0001 |

| Katy Perry | 22% | 6% | <.0001 |

Excludes 206 tweets that appeared to use the terms casually or in a humorous manner, or referenced depression caused by trivial things

Typical Twitter user demographics are based on a random sample of 20,000 English-language Twitter handles from the U.S. and Canada.

Most of the individuals who tweeted about feeling depressed were inferred to be Caucasian (52%). This prevalence is lower when compared against the typical Twitter user (64% Caucasian). More tweeters who disclosed feeling depressed were African American than the typical Twitter user (35% versus 24%).

4. Discussion

The present study examined the depression-related chatter on Twitter over the course of about one month (April 11 to May 4, 2014) in order to glean insight into the conversation and social networking that is occurring about depression on this popular social media platform. Over this time period, over 1.5 million tweets were collected (over 70,000 per day), showing the considerable presence of social networking about depression on Twitter. We additionally studied the content of a random sample of these tweets, and inferred within our research team that the most common theme was supportive or helpful tweets about depression. Past studies have found that the internet is widely used for information seeking and/or to engage in peer support exchanges for many health-related issues including depression (Moreno et al., 2011; Moreno et al., 2012). Our findings add to this emerging field of research by identifying Twitter as a social media platform where individuals likewise deliver and/or garner support or helpful advice about depression. We do not know the extent to which supportive/helpful tweets help individuals to cope with depression but we do see this as an important next step.

Another common theme that we identified was that the Tweeter was disclosing feelings of depression. Furthermore, two-thirds of these tweets appeared to reveal one or more symptoms consistent with the diagnosis of MDD and/or communicated thoughts or ideas that were consistent with struggles of depression. The most common symptoms we observed in these tweets included chronic feelings of a depressed or irritable mood and guilt/worthlessness. Thus, our findings indicate that some individuals are forthcoming about their mental health struggles via postings on Twitter which corresponds with Park et al. (2012) who likewise found that individuals tweet about their depression and even disclosed updates about their mental health treatment on Twitter. Moreover, we found tweets where thoughts about self-harm and/or suicide were mentioned. When extended to the full sample of tweets, we estimate nearly 700 tweets per day are posted that entail thoughts about self-harm and/or suicide.

We are unable to determine the degree to which the tweets that we examined do correspond with self-reported depression and/or suicidal intent, and a more in-depth study on this topic is an important next step in this line of research. Nevertheless, it is indeed worrisome that individuals are socially networking about these topics, especially when the posts involve self-harm and suicidal thoughts. This is especially concerning given the surmounting evidence supporting the social contagion of suicidality (Daine et al., 2013; Gould & Davidson, 1988; Niedzwiedz, Haw, Hawton, & Platt, 2014; O’Carroll & Potter, 1994). Our study is exploratory and as a whole, social media research is a relatively new field of research. Thus, it is relevant to understand the effects of these posts among individuals who view them because young people tend to be highly impressionable to media messages and peer influences, in general.

Given the relatively high prevalence of tweets that reflected one or more symptoms for the diagnosis of MDD and/or communicated thoughts or ideas that were consistent with feeling depressed, we focused our demographic analysis on these Tweeters. We note that Caucasian girls/women were inferred to be the most likely Tweeters of depression-related content, and African Americans also had a dominant presence among the Tweeters. Epidemiological studies similarly note MDD prevalence rates that are in-line with the gender and racial/ethnic differences we observed among the Tweeters (Howell, Brawman-Mintzer, Monnier, & Yonkers, 2001; Kessler, 2003). In fact, the prevalence of depression has been consistently documented at about twice as high in females versus males (Kessler, 2003). Our findings are also consistent with research that has found differences in social media use between African Americans versus Caucasians (Madden et al., 2013). In general, African Americans have a high presence on Twitter (Madden et al., 2013). African American youth are less likely to disclose their real name on a social media profile, and this anonymity may facilitate their openness to discussing depression-related content on Twitter (Madden, et al., 2013). Whatever the case may be, our study provides a snapshot into the inferred demographic characteristics of individuals whose tweets are disclosing struggles with depression.

We additionally found that the Tweeters in our study tended to follow the same popular culture celebrities. Best practices for incorporating social media trends and insights health-related interventions have not yet been established. However, it may be useful for mental health-related organizations that currently use Twitter to strategize ways to tailor their tweets to match the ages and hobbies/interests of individuals who are disclosing feelings of depression in their tweets. For example, on August 30, 2014, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline tweeted, “Musician Rhett Miller talks about his suicide attempt and why he is glad the Lifeline is here to help. http://ow.ly/ASkwI”. Another example is Demi Lovato who is a young adult celebrity who is popular with a young demographic and has advocated on behalf of mental health issues, including tweets such as “It’s NAMI’s National Day of Action!! Pass comprehensive mental health legislation #mentalhealth #Act4MentalHealth” which was tweeted on September 4, 2014. Suicide prevention organizations are encouraged to strategize ways to incorporate music, education, or popular culture into their efforts perhaps by partnering with celebrities to deliver prevention messages about suicide and depression.

Because Twitter limits user’s posts to 140 characters, the depth of content can be lacking. This restricted the amount of information users could give about their feelings of depression, and therefore, all causes about the Tweeter’s depression were often not given within the tweets that we examined. The findings of the study are based on a random sample of 2,000 depression-related tweets sent in a 24-day period. Therefore, more tweets examined over an extended time period could produce more thorough findings. We did not monitor popular terms like “sad”, “unhappy”, and “miserable” because they are commonly used to describe temporary states or moods and would have likely generated a much higher number of trivial tweets. However, a more extensive list of keywords to monitor could have led to more comprehensive findings. We are unable to make any conclusions about the type of individuals who are willing to share personal information about depression openly online compared with those who do not choose to socially network in this way. For instance, there are some individuals with depression who likely suffer from social anxiety (Keller, 2006) and use Twitter to socially network because they experience less social anxiety interacting online when compared to offline interactions (Yen et al., 2011). Finally, Demographics Pro infers demographic characteristics of Twitter users, so although their methods are deemed to be accurate, it’s possible that the inferred characteristics of the Tweeters do not represent the actual Twitter users in our sample of tweets. Similarly, the “typical Twitter user” comparison group is limited to the United States and Canada and is not an exact match of our sample of Tweeters; most of our Tweeters are inferred to be from the United States and Canada (78%) while 9% are from United Kingdom and 13% are from another country.

Despite these limitations, the present study offers a unique understanding of the role of social media in the expression of depression. Twitter is one of the most widely used social media platforms especially among young people, and we found that many individuals are posting supportive or helpful tweets about depression. However, we also found a relatively high prevalence of tweets that revealed one or more symptoms for the diagnosis of MDD and/or communicated thoughts or ideas that were consistent with feeling depressed. Our study is unique in its examination of a broad sample of depression-related tweets for identification of common themes and symptoms as well as Tweeter’s demographic characteristics and interests. We hope that our findings can be used by mental health professionals to tailor and target prevention and awareness messages to those Twitter users who are most in need.

Highlights.

Many posts about depression on Twitter are supportive/helpful tweets.

Twitter users also commonly disclose feelings of depression in their Tweets.

Tweets reveal symptoms consistent with the diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder.

Research is needed on how tweets relate to self-reported depression.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from NIH R01DA032843 (PCR), NIH R01DA039455 (PCR)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D.C: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S. Twitter USA: 48.2 Million Users Now, Reaching 20% Of Population By 2018. Mediabistro. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.mediabistro.com/alltwitter/twitter-usa-users_b55352.

- Bland RC, Newman SC, Orn H. Help-seeking for psychiatric disorders. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;42(9):935–942. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner J. Pew Internet: Social Networking. Pew Internet & American Life Project. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/social-networking-fact-sheet/

- Daine K, Hawton K, Singaravelu V, Stewart A, Simkin S, Montgomery P. The power of the Web: a systematic review of studies of the influence of the Internet on self-harm and suicide in young people. PloS One. 2013;8(10):e77555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077555. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Choudhury M, Gamon M, Counts S, Horvitz E. Predicting Depression via Social Media. Seventh International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.2013. [Google Scholar]

- De Cristofaro E, Soriente C, Tsudik G, Williams A. Hummingbird: Privacy at the time of twitter. Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP’12); IEEE Computer Society; May, 2012. pp. 285–299. doi:10.1109/SP.2012.26. [Google Scholar]

- Demographics Pro for Twitter 2014 Retrieved from http://www.demographicspro.com/

- Dew MA, Dunn LO, Bromet EJ, Schulberg HC. Factors affecting help-seeking during depression in a community sample. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1988;14(3):223–234. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan M, Ellison NB, Lampe C, Lenhart A, Madden M. Social Media Update 2014: Pew Research Center. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/01/09/social-media-update-2014.

- Duggan M, Smith A. Social Media Update. Pew Internet & American Life Project. 2013 Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Social-Media-Update.aspx.

- Edwards J. Facebook is no longer the most popular social network for teens. Business Insider. 2013 Oct 24; Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/facebook-and-teen-user-trends-2013-10.

- Egan KG, Moreno MA. Alcohol references on undergraduate males’ facebook profiles. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2011;5(5):413–420. doi: 10.1177/1557988310394341. doi:10.1177/1557988310394341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Downs MF, Golberstein E, Zivin K. Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Medical Care Research and Review. 2009;66(5):522–541. doi: 10.1177/1077558709335173. doi:10.1177/1077558709335173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans E, Hawton K, Rodham K. Factors associated with suicidal phenomena in adolescents: A systematic review of population-based studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24(8):957–979. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.04.005. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, Davidson L. Suicide contagion among adolescents. Advances in Adolescent Mental Health. 1988;3:29–59. [Google Scholar]

- Guitton MJ. The importance of studying the dark side of social networks. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;31:355. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.055. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn JF, Lester D. Twitter postings and suicide: An analysis of the postings of a fatal suicide in the 24 hours prior to death. Suicidologi. 2012;17(3):28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Saunders KEA, O’Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2373–2382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell HB, Brawman-Mintzer O, Monnier J, Yonkers KA. Generalized anxiety disorder in women. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2001;24(1):165–178. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70212-4. doi:10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jashinsky J, Burton SH, Hanson CL, West J, Giraud-Carrier C, Barnes MD, Argyle T. Tracking suicide risk factors through Twitter in the US. Crisis. 2015;35(1):51–59. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000234. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB. Social anxiety disorder clinical course and outcome: review of Harvard/Brown Anxiety Research Project (HARP) findings. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 12):14–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. Epidemiology of women and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;74(1):5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00426-3. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Borges G, Nock M, Wang PS. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990-1992 to 2001-2003. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293(20):2487–2495. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2487. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klout Inc The Klout Score. 2014 Retrieved from https://klout.com/corp/score.

- Lenhart A, Duggan M, Perrin A, Stepler R, Rainie L, Parker K. Teens, social media & technology overview 2015. Pew Research Center. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/files/2015/04/PI_TeensandTech_Update2015_0409151.pdf.

- Madden M, Lenhart A, Cortesi S, Gasser U, Duggan M, Smith A, Beaton M. Teens, Social Media, and Privacy. Pew Internet & American Life Project. 2013 May 21; Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/files/2013/05/PIP_TeensSocialMediaandPrivacy_PDF.pdf.

- Marwick AE. I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society. 2011;13(1):114–133. doi:10.1177/1461444810365313. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno MA, Jelenchick LA, Egan KG, Cox E, Young H, Gannon KE, Becker T. Feeling bad on Facebook: Depression disclosures by college students on a social networking site. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28(6):447–455. doi: 10.1002/da.20805. doi:10.1002/da.20805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno MA, Christakis DA, Egan KG, Jelenchick LA, Cox E, Young H, Villiard H, Becker T. A pilot evaluation of associations between displayed depression references on Facebook and self-reported depression using a clinical scale. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2012;39(3):295–304. doi: 10.1007/s11414-011-9258-7. doi:10.1007/s11414-011-9258-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedzwiedz C, Haw C, Hawton K, Platt S. The definition and epidemiology of clusters of suicidal behavior: a systematic review. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2014;44(5):569–581. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12091. doi:10.1111/sltb.12091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Carroll PW, Potter LB. Suicide contagion and the reporting of suicide: Recommendations from a national workshop. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Recommendations and Reports. 1994:9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M, Cha C, Cha M. Depressive moods of users portrayed in Twitter. Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD Workshop on Healthcare Informatics (HIKDD).2012. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff JJ, Almeida OP. Identifying suicidal ideation among older adults in a general practice setting. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;83(1):73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.03.006. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003;15(1):85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Simply Measured 2014 Retrieved from http://simplymeasured.com/

- Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Friedman SJ, Meyers BS. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(12):1615–1620. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1615. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sueki H. The effect of suicide-related Internet use on users’ mental health. Crisis. 2015;34(5):348–353. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000201. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tappin S. Facebook vs. Twitter: Who wins the battle for our social attention? 2014 Jul 29; Retrieved from http://pando.com/2014/02/06/facebook-vs-twitter-who-wins-the-battle-for-our-social-attention/

- Yen J-Y, Yen C-F, Chen C-S, Wang P-W, Chang Y-H, Ko C-H. Social Anxiety in Online and Real-Life Interaction and Their Associated Factors. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2011;15(1):7–12. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2011.0015. doi:10.1089/cyber.2011.0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]