Abstract

Patient: Male, 70

Final Diagnosis: Cardiogenic shock

Symptoms: Chest discomfort and intermittent palpitations

Medication: Amiodarone

Clinical Procedure: Intubation

Specialty: Cardiology

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Amiodarone is frequently used in emergency departments for treatment of arrhythmias. Incidence of several amiodarone-related adverse events is unknown. The literature is sparse for potentially life-threatening adverse effects of amiodarone.

Case Report:

We present a case of a male patient who presented with chest discomfort and rapid atrial fibrillation. He was known to have paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, which did not respond to initial beta-blocker treatment. The second-line drug amiodarone was given to the patient for rate control. He developed severe hypotension related to amiodarone and required inotropic support along with rapid-sequence intubation.

Conclusions:

Intravenous amiodarone can cause severe and refractory hypotension.

MeSH Keywords: Amiodarone, Atrial Fibrillation, Hypotension

Background

Amiodarone is used for treatment of life-threatening arrhythmias in emergency departments. Amiodarone is one of the most effective antiarrhythmic drugs available, but it has a narrow therapeutic index and high risk of toxicity. It prolongs the refractory period in all cardiac muscles. Gastrointestinal disturbances, including hepatic dysfunction, hypothyroidism, pulmonary toxicity, and neuropathy, are widely described in the literature. Amiodarone can cause potentially life-threatening refractory hypotension, which we have described in this case report.

Case Report

A 70-year-old man presented to emergency department with chest discomfort and intermittent palpitations. His chest discomfort had increased for the past 2 hours before he presented to the emergency department. He had nausea but not diaphoresis or vomiting. He did not have breathing difficulty or fever. On examination he was alert and appeared to be in moderate discomfort. His right radial pulse rate was 160 beats per min, which was irregularly irregular with good volume. The left upper-arm blood pressure was 150/95 on digital recording. His oxygen saturation was 96% at room air with a respiratory rate of 20 per min. His temperature was 36.4°C on tympanometric measurement. Cardiac examination confirmed irregular heart sounds without any murmur. Bilateral respiratory sounds were vesicular. Jugular venous pressure on palpation of liver was not elevated. There was no evidence of pedal edema.

He was previously diagnosed to have paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. His regular medications included bisoprolol, dabigatran, ramipril, and rosuvastatin. A recent echocardiogram was consistent with his diagnosis and had mildly dilated left ventricle. Coronary angiogram performed a year ago showed mild triple-vessel disease.

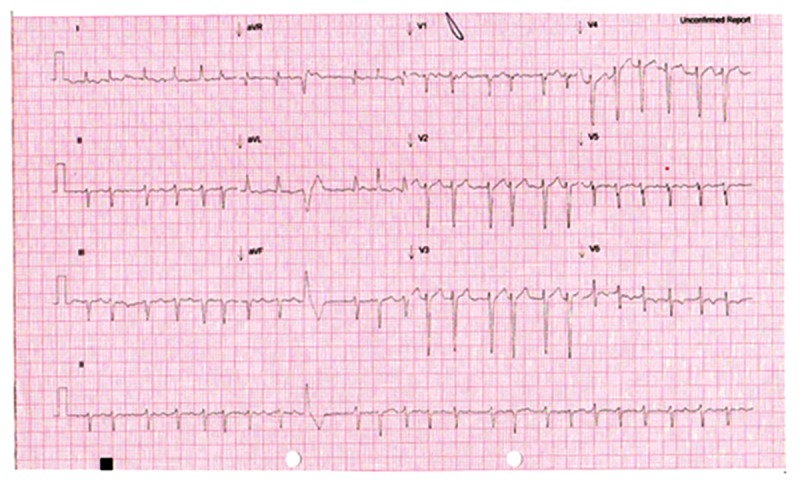

At presentation, the initial electrocardiogram showed atrial fibrillation with fast ventricular response with no ischemic changes (Figure 1). Chest x-ray confirmed cardiomegaly. Lung fields were normal on chest x-ray and there was no sign of congestive cardiac failure. Blood test showed normal full blood count, and urea and electrolytes were normal. Laboratory and point-of-care tests for blood glucose were within normal range. High sensitive troponin at the time of presentation, which was 3 hours after onset of symptoms, was 14 ng/L (reference range <15 ng/L).

Figure 1.

ECG 1: Initial ECG showing atrial fibrillation.

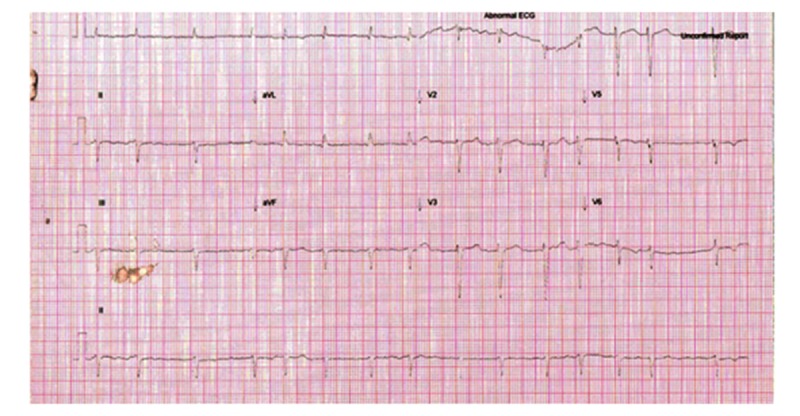

He was treated with oral bisoprolol, which did not have any effect on his tachycardia after over an hour. Amiodarone (Cordarone X intravenous – Sanofi Aventis) was commenced as an intravenous loading dose of 300 mg over 30 min. Within minutes of starting amiodarone, the patient became agitated and diaphoretic. Repeat electrocardiogram had no dynamic changes to his ST or T segment (Figure 2). His blood pressure started to drop below 90 systolic. A test dose of fluid did not have any effect. There were no features of acute anaphylactic reaction. He complained of epigastric pain and soon became cyanotic with loss of consciousness. Ventricular rate dropped to 70 per min and irregular. Blood pressure was not recordable. Amiodarone infusion was stopped. He was immediately intubated and inotropic infusion of noradrenaline 0.4mg/h was started. He continued to remain hypotensive in the systolic blood pressure range of 60 to 70 mmHg. A second inotropic drug, dobutamine, was commenced. Bedside echocardiogram revealed severe left ventricular dysfunction. CT thoracic angiogram was negative for acute aortic dissection. There was no evidence of central pulmonary emboli. All subsequent troponin levels were within normal range. He was stabilized in the emergency department and then transferred to the intensive care unit.

Figure 2.

ECG 2: Repeat ECG: Atrial fibrillation with slower rate. No signs of myocardial infarction.

In the week following intensive care admission, he had a transoesophageal echocardiogram, which was consistent with the previous echocardiographic results. He had no vegetation on the valves. Electrical cardioversion was successfully performed.

Discussion

Amiodarone is an iodinated benzofuran derivative used for the treatment of both supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias. It acts through interference with potassium (class III), sodium (class I), and calcium (class IV) [1–4]. It also has beta-blocking (class II) effects [5]. However, it is generally considered as a class III antiarrhythmic agent according to the Vaughan-Williams classification. Its long-term adverse effects, including thyroid and pulmonary toxicities, are well established.

In the acute setting, amiodarone can cause hypotension due to vasodilation and depression of myocardial contractility; this may be partly due to the solvent, polysorbate 80 or benzyl alcohol, used to assist in dissolving the drug [6–8]. Experimental studies with administration of amiodarone with a relatively non-toxic co-solvent such as cyclodextrin instead of polysorbate 80 and benzyl alcohol is known to be devoid of myocardial depressant effect [9]. In regards to treatment of intravenous amiodarone-induced acute hypotension, lipid emulsion has been suggested as an antidote. Intravenously-administered lipid emulsion has been used successfully in a study done in animals to reverse intravenous amiodarone-induced hypotension [10] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Adverse effects of amiodarone.

| System affected | Adverse effect |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Conduction abnormalities Heart block Prolongs the QT interval |

| Endocrine | Hypothyroidism Hyperthyroidism |

| Pulmonary | Eosinophilic lung infiltrate Pulmonary fibrosis |

| Skin | Allergic rash Photosensitivity Blue-gray skin discoloration |

| Gastrointestinal | Nausea Vomiting Anorexia Constipation Hepatitis Liver failure |

| Nervous system | Tremor Ataxia Peripheral neuropathy Fatigue |

| Eye | Corneal micro-deposits Macular degeneration |

Reference: MIMS (Monthly Index of Medical Specialties. www.mims.com.au, last access Jan 2015.

There were several case reports on acute hypotension with intravenous amiodarone use thought to be due to anaphylactic reaction [11,12]. To the best of our knowledge, all the available case reports on amiodarone anaphylaxis have shown other associated symptoms or signs of an allergic reaction such as angioedema or urticaria in association with hypotension with a rapid improvement of hypotension after ceasing amiodarone infusion. Other causes of cardiogenic shock (e.g., massive myocardial ischemia) were excluded with repeat ECGs and troponin levels. There were no clinical features of sepsis or any other causes of hypotension.

This case report is unique in that the patient developed life-threatening refractory hypotension within minutes of completion of amiodarone bolus dose, with no other features of anaphylaxis. To the best of our knowledge, this adverse effect is described in the drug manuals based on animal studies, but no human study of this has been published. With echocardiographic evidence of severe left ventricular dysfunction and absence of other clinical features of anaphylaxis, cardiogenic shock was thought to be the likely explanation. Severe cardiogenic shock immediately following therapeutic doses of amiodarone infusion is a very rare adverse event. The likely cause for acute severe hypotension is the co-solvent used to dissolve amiodarone.

Physicians using current formulations of intravenous amiodarone should be aware of its life-threatening acute adverse effects such as severe hypotension secondary to cardiogenic shock. The pharmaceutical industry should be encouraged to develop newer formulations of amiodarone with better co-solvents to prevent potentially fatal acute adverse effects of intravenous amiodarone. In addition, more studies should be done to develop an antidote for amiodarone-induced hypotension such as lipid emulsion until better intravenous amiodarone preparations are made available to clinicians.

Conclusions

Intravenous amiodarone can cause severe and refractory hypotension. Clinicians using amiodarone should be aware of and be prepared to deal with serious adverse effects of amiodarone in the acute setting.

Footnotes

Statement

No financial support. No conflict of interest.

References:

- 1.Ravishankar R, Samuels LE, Kaufman MS, et al. Amiodarone associated hemoptysis. Am J Med Sci. 1998;316:390–92. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199812000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanguinetti MC, Jurkiewicz NK. Block of a novel cardiac K+ current by calss III antiarrhythmic agents. Circulation. 1989;80:S607. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Follmer C, Aomine M, Yeh J, Singer DH. Amiodarone induced block of sodium current in isolated cardiac cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;243:187–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishimura M, Follmer CH, Singer DH. Amiodarone blocks calcium current in single guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251:650–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coker SJ, Chess-Williams WR. Amiodarone, adrenoceptor responsiveness and ischaemia and reperfusion-induced arrhythmias. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;201:103–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90329-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Goodman Gilman A, editors. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 10th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kudenchuk PJ, Cobb LA, Copass MK, et al. Amiodarone for resuscitation after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation. N Eng J Med. 1999;341:871–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909163411203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cushing DJ, Cooper WD, Gralinski MR, Lipicky RJ. The hypotensive effect of intravenous amiodarone is sustained throughout the maintenance infusion period. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2010;37(3):358–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cushing DJ, Kowey PR, Cooper WD, et al. PM101: A cyclodextrin-based intravenous formulation of amiodarone devoid of adverse hemodynamic effects. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;607:167–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niiya T, Litonius E, Petaja L, et al. Intravenous lipid emulsion sequesters amiodarone in plasma and eliminates its hypotensive action in pigs. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(4):402–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.06.001. e402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurt ÝH, Yalcin F. Anaphylactic shock due to intravenous amiodarone. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:265.e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okuyan H, Altin C, Arihan O. Anaphylaxis during intravenous administration of amiodarone. Ann Card Anaesth. 2013;16:229–30. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.114251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]