Abstract

The hallmarks of persistent viral infections are exhaustion of virus-specific T cells, elevated production of interleukin 10 (IL-10) and programmed death-1 (PD-1) the dominant negative regulators of the immune system and disruption of secondary lymphoid tissues. Within the first 12–24 hours after mice are infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) clone 13, which is used as a model of persistent virus infection, we note generation of high titers of type 1 interferon. Blockade of type 1 interferon significantly lessens IL-10 and PD-1/PD-L1, allows normal secondary lymphoid architecture and re-establishes antiviral T-cell function, thus eradicating the virus and clearing the infection. Hence, type 1 interferon is a master reostat for establishing persistent viral infection.

Keywords: type 1 interferon, persistent viral infection, regulation of IL-10 and PD-1/PD-L1

Hilary Koprowski was a most fascinating man and scientist. I had the pleasure of his company as a friend, traveling companion, and colleague for over 35 years. A renaissance man who loved fine things and real surprises, Hilary would have been tickled by the recent unusual finding made in my laboratory. We found that type 1 interferon (IFN), like the good Dr Jekyll's evil side, Mr Hyde, can be harmful for its host [1]. In addition to the Dr Jekyll-like beneficial roles of antiviral and anti-tumor phenotypes associated with antiviral or anti-tumor T-cell generation, my colleagues and I at Scripps found a sinister Mr Hyde role. That is, type 1 IFN can signal the up-regulation of interleukin 10 (IL-10) and programmed death-1 (PD-1)/PD-L1, molecules associated with T-cell exhaustion, resulting in a persisting virus infection. This discussion of IFN-1's opposing sides, initially found in the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) clone (Cl) 13 model of persistent infection [1, 2] and later extended to human viral infections, is dedicated to Hilary.

Animal models are routinely used to dissect and understand mechanisms of human diseases. One would certainly agree that the best model of any human disease is a human with that disease. However, it would be lunacy to believe that the available clinical pictures and biomarkers present in humans are by themselves often sufficient to understand the pathogenesis of disease. Take diabetes as an example, a disease that embodies very good indicators, such as elevated blood glucose and low insulin levels, along with antibodies and specific T cells that recognize and interact with molecules on pancreatic islets. An estimated 75% or more β cells, the cells that make insulin, must be destroyed before blood glucose levels become clinically abnormal enough to prompt the diagnosis. A number of years before glucose/insulin malfunction is evident, antibodies to antigens on/in pancreatic islet cells are recognizable biomarkers signaling the likelihood that diabetes will occur [3, 4]. Other biomarkers prospectively indicate islet-specific cytolytic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Both factors define events in the circulation to judge correlations with a disease occurring in the islets [5]. Thus it is not possible to know whether those actions occur with appropriate timing and within the vicinity or milieu of islet cells. CTLs are considered to have the ability for direct lysis of beta cells in the islets of Langerhans [5, 6] or to be a necessary cell that recognizes cells to be destroyed. In the second scenario by the release of cytokines/chemokines, the CTL attracts cells of the myeloid lineage, that is, macrophages that perform the killing of islets [7]. Again, because neither antibodies nor T-cell biomarkers in the circulation reflect what occurs in the microenvironment of the islet cell, one cannot clearly establish the etiology, degree, and/or molecular mechanism of islet cell damage during current examining of patients.

Identification of biomarkers for other autoimmune disorders, like multiple sclerosis (MS), is even further in the future than for diabetes in terms of adequately defining the disease or its resolution. Thus, the intrinsic weakness of attempting to study diseases in living patients is that the microenvironment of affected tissues is difficult or impossible to access (eg, the pancreas in diabetics or oligodendrocytes/neurons in patients with MS). The recent flurry of articles denigrating or questioning experimental studies in mice [8, 9] not only seems but is shallow and fails to recognize the well-substantiated experience over several decades of animal studies that have provided great insight into human diseases. Of course, experimentalists must select the appropriate disease or biologic phenomena to study in a model system and then ensure that resulting observations relate to the human situation or pathologic condition. Some correlations are too limited for the application of outcomes in mice or other animals for translational human research as there is no or limited correlation. However, most often, superb correlations have frequently emerged between animal models and human disorders. For example, the basic knowledge about antiviral T cells, that is, their generation, expansion, function, and memory phenotype in humans, came from animal experimentations as did the finding of T-cell exhaustion and identification of the negative immune regulators (PD-1/PD-L1; IL-10, LAG3, etc.). All came from work with LCMV infection of mice [10–27] and was later applied to understanding human persistent infections such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C, or hepatitis B viruses, as well as herpes and cytomegaloviruses [28–36].

Over the last 4 decades basic research using the murine model of LCMV has illuminated our understanding of the biologic systems and pathogenesis of human viral infections [reviewed 10, 11]. Down-regulation of the function of antiviral T cells or T-cell exhaustion is now known to be the central tenet of persistent viral infections in humans but was first described after studies with LCMV in the laboratory [12]. Indeed, the first documentation that lymphocytes kill virus-infected targets [13, 14], identification of the killer cells as T cells [15], and understanding that major histocompatability complex (MHC) restriction was the primary requirement for virus-specific T-cell recognition, killing, or cytokine/chemokine release [16], all originated while using the LCMV/murine model by investigators from multiple laboratories long before these processes were shown to be essential in human infections. The LCMV model was also used to provide evidence that adoptive transfer of splenic memory cells [17] or removing CD8+ T and CD4+ T cells from the persistently infected host and culturing them away from the viral excess found in persistent infections, restored T-cell function. Those virus-free T cells then reinstated the functions required to clear the viral infection [18].

The next essential step was to determine the mechanism by which T-cell exhaustion [12] occurred. Work from the laboratory or Rafi Ahmed and ours independently established that the infecting virus induced and maintained negative immune regulators (NIRs) [reviewed 19]. Again, LCMV Cl 13 infection of mice provided the environment in which NIRs and PD-1 cell receptors were first identified [19–26]. Among the many NIRs and receptors now known, the first 2 described, IL-10 [21, 22] and PD-1/PD-L1 [20], appear to be the most important. So far, these 2 are considered the major immunodominant NIRs as they alone, by genetic deletion or specific antibody neutralization, restore functionality to exhausted T cells. In contrast, other NIRs [19, 27] apparently do not act alone to restore T-cell functionality but work primarily by cooperating with an immunodominant NIR. We propose labeling this family of NIRs and cell receptors as subdominant. Later, these NIRs and cell receptors were also found operational for persistent virus infections of humans [28–35]. Interestingly, the IL-10 and PD-1/PD-L1 effect occurs via separate pathways, because the blockade of one does not affect the other [36]. A major thrust currently under way by the pharmaceutical industry is the discovery and usage of novel small pharmacologic molecules and improvement of known NIRs for their therapeutic applications in clinical medicine for treatment of both persistent viral infections as well as cancers in humans.

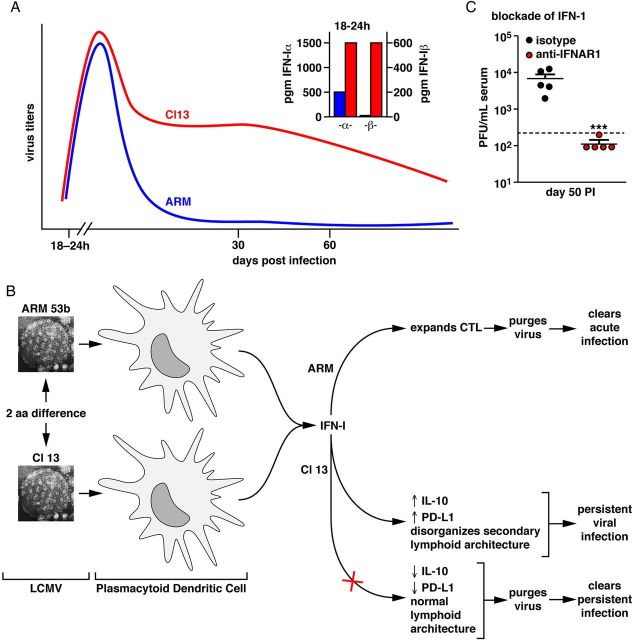

The perception of NIRs’ regulation and T-cell exhaustion recently underwent a paradigm shift. Interferon (IFN) 1 was found to be the master regulator of IL-10 and PD-1/PD-L1, because blockade of IFN-1 signaling by monoclonal antibody diminished IL-10 and PD-1/PD-L1 levels (Figures 1 and 2), restored the previously diminished or lost T-cell function and cleared virus [1, 2]. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (DCs) are the major cells producing IFN-1, which is robustly made during the first 24 hours of LCMV Cl 13 infection [1, 2] (Figure 1). Thus, blockage of type 1 IFN signaling with a monoclonal antibody against the IFN-1α-β receptor reduced IL-10, PD-1/PD-L1 content, restored T-cell trafficking in the lymphoid tissues and thereby restored T-cell function (Figure 2). As a result the persisting virus was purged (Figure 1). This association of IFN type 1 with excessive viral replication govern the regulation of NIR that lead to T-cell exhaustion. Current investigations are focused on how IFN-1 can be both antiviral and also proviral and what molecular mechanisms participate. Efforts are under way in several laboratories to see if IFN-1 signaling and/or IFN signatures found in mice resemble those in humans with persistent viral infections. The motivation is that a blockade of IFN-1 signaling with neutralizing antibody or by small molecules early in infection or later when T cells are exhausted could be a therapeutic solution to control persistent human viral infections as well as several human cancers.

Figure 1.

Comparison of infection pathways for LCMV ARM and LCMV Cl 13. Upper panel A, Viral titers of LCMV ARM (blue) and LCMV Cl 13 (red) following their injection (2 × 106 PFU iv) into C57Bl/6 mice are shown, as is the release of IFN-α and IFN-β at 18–24 h following each virus infection. Lower left and center panel B, Display of the EM portrait of LCMV ARM and LCMV Cl 13. Cl 13 differ from ARM in only 3 amino acids of the virion's total 3356 amino acids; only 2 amino acid differences lead to the vastly different phenotypes listed. LCMV Cl 13 infects significantly more plasmacytoid DCs, the major cell type producing IFN-1, than does LCMV ARM. Panel C, Display of the blockade of IFN-1α,β receptor signaling (red dot for each individual mouse) that purges virus and clears the LCMV Cl 13 infection compared to an isologous non-IFN-1 blocking antibody (black dot for each individual mouse). Abbreviations: ARM, Armstrong; EM, effector memory; IFN, interferon; LCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus; PFU, plaque-forming unit.

Figure 2.

Regulation of markers of viral infection by IFN-1. Panel A, Display that IFN-1 is a major regulator of IL-10 and PD-1/PD-L1 the immunodominant molecules associated with and causing T-cell exhaustion. Note that a blockade of IFN-1α,βrec signaling significantly reduces IL-10 and PD-L1 levels during LCMV Cl 13 infection. Panel B, Displays of the total distortion of splenic cell architecture by LCMV Cl 13 infection; in contrast, that architecture is preserved when antibody to IFN-α,βrec blocks IFN-1 signaling. Panel C, Records of the preferential infection of plasmacytoid DCs by LCMV Cl 13 compared to that by LCMV ARM. IFN-β indicator YFP expression in plasmacytoid (pDC) and conventional dendritic cell subsets, CD4, CD8, NK, or macrophages are shown in the 2 inserts on the left. The right insert displays pDCs preferentially infected early after Cl 13 infection. Percent of GFP-positive pDCs infected with ΔGP-Cl 13 or ΔGP-ARM viruses at 24 h post-infection are shown (see ref [1] for details). Panel D, Summary of the role of IFN-1 signaling in initiating and maintaining a persistent virus infection. Abbreviations: ARM, Armstrong; DC, dendritic cell; GFP, green fluorescent protein; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; LCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus; NK, natural killer; PD, programmed death; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein.

A blockade of IFN-1 signaling maintained splenic architecture. That is, the follicle containing white pulp was now not destroyed during a persistent viral infection [1]. This structure is necessary for the migration of naive T cells through secondary lymphoid tissues for their encounter with DCs, the cells that present viral antigens. When DC T-cell interaction occurs, virus-specific T cells can then be programmed and expanded, thereby enabling them to control the existing viral infection. A blockade of IFN-1α,β receptor signaling significantly ameliorated amounts of IL-10 and PD-1/PD-L1, the 2 immunodominant negative regulators clearly indicating that IFN-1 signaling was a master regulator of these molecules and essential for the initial expression and maintenance. To reiterate, with the establishment of a persistent LCMV infection, antiviral T-cell exhaustion is associated with up-regulation of IL-10 and PD-1/PD-L1 leading to an increase in virus and disordered secondary lymphoid architecture, a portrait also observed with HIV infection. Importantly, use of an animal model allows us to explore by 2-photon microscopy the trafficking of T cells into disordered splenic lymphoid organs. Because IFN-1α,β receptor signaling initiated that T-cell migratory behavior, comparable trafficking into mice, whose IFN-1 signaling was blocked by specific neutralizing antibody to IFN-1α,β receptors, provides a window of opportunity for careful monitoring of cell and molecular events not otherwise available.

Such experiments have been undertaken by Cherie Ng in my laboratory, in collaboration with Dorian McGavern's unit at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). There, 2-photon microscopy and immunochemical assay are used for in vivo analysis of migration and velocity of naive and LCMV-specific primed CD8 and CD4 T cells in the LCMV Cl 13 model in the presence and absence of type 1 IFN signaling. Other studies have identified, quantitated, and blocked several cytokines/chemokines that control or retard the trafficking events in the disordered or in the corrected splenic architecture. Additional analyses in my laboratory are reexploring and marking the earliest cells that become infected by LCMV Cl 13. The purpose is to see if cells other than plasmacytoid DCs are involved and contribute to the release of IFN. Finally, we are evaluating different strategies used by LCMV Cl 13 compared to LCMV Armstrong (ARM) for signaling the IFN-1α,β receptor (Figure 1). Of a total 3356 amino acids, the Cl 13 strain differs from the ARM strain by only 3 amino acids [37–39]. Of these, only 2, Cl 13/ARM GP260 Leu/Phe and polymerase 1079 Gln/Lys, determine whether virus persists and T-cell exhaustion occurs (Cl 13) or, in contrast, a robust virus-specific T-cell response is made, and virus is cleared (ARM). The molecular basis for this observation [37–42] is that the Cl 13 which contains at GP 260 Leu, a small aliphatic amino acid, binds at 2.5 logs higher affinity to the LCMV receptor alpha-dystroglycan (α-DG) than LCMV ARM, which has a bulky aromatic acid Phe at the GP 260 position and binds minimally. α-DG is preferentially located on dendritic cells (DC) [37, 40–42], and this accounts for the high percentage of DCs infected with LCMV Cl 13 (30%–50%) as compared to <5% for LCMV ARM. In addition, Cl 13 generates significantly greater type 1 IFN-α and -β responses 12–24 hours postinfection than does ARM [1, 2] (Figure 1). A blockade of IFN type 1 signaling during Cl 13 infection generates the virus-specific T-cell response and control of virus infection; however, a similar blockade of IFN type 1 signaling during ARM infection halts CTL generation, leading to excessive virus replication [1]. The dichotomy between α and β responses and between Cl 13 and ARM infections suggests that unique molecular and signaling pathways await discovery and foretells surprises. Unfortunately, we will not be able to share such novel findings of IFN-1 signaling with Hilary, unless of course he knows something that we don't!

Notes

Acknowledgments. The recent and current investigations of IFN-1 are undertaken in my laboratory by Cherie Ng, John Teijaro, and Brian Sullivan. The 2-photon microscopy is in collaboration with Dorian McGavern and his group at the NIH. Past studies of NIR and plasmacytoid DCs were begun by David Brooks and Elina Zuniga when postdoctoral fellows in my laboratory, now Associate Professors at UCLA and UCSD, respectively. Studies on the initial discovery of LCMV Cl 13, its sequencing and genetics, as well as trafficking of LCMV Cl 13 to the white pulp were done by past postdoctoral fellows Rafi Ahmed, Maria Salvato, Persephone Borrow, Claire Evans, Stefan Kunz, Noemi Sevilla, Sara Smelt, Brian Sullivan, and Dan Popkin. Studies on reverse genetics of LCMV were performed by and in part with my colleague, Juan Carlos de la Torre, a Professor at TSRI, his former postdoctoral fellow Sebastien Emonet, and later my postdoctoral fellows Brian Sullivan and Dan Popkin.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award R01 AI009484.

Potential conflicts of interest. The author reports no potential conflicts.

The author has submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Teijaro JR, Ng C, Lee AM, et al. Persistent LCMV infection is controlled by blockade of type I interferon signaling. Science 2013; 340:207–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson EB, Yamada DH, Elsaesser H, et al. Blockade of chronic type I interferon signaling to control persistent LCMV infection. Science 2013; 340:202–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pihoker C, Gilliam LK, Hampe CS, Lernmark A. Autoantibodies in diabetes. Diabetes 2005; 54(suppl 2):S52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Notkins AL, Lernmark A. Autoimmune type 1 diabetes: Resolved and unresolved issues. J Clin Invest 2001; 108:1247–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coppieters KT, Dotta F, Amirian N, et al. Demonstration of islet-autoreactive CD8 T cells in insulitic lesions from recent onset and long-term type 1 diabetes patients. J Exp Med 2012; 209:51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coppieters K, Amirian N, von Herrath M. Intravital imaging of CTLs killing islet cells in diabetic mice. J Clin Invest 2012; 122:119–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JV, Kang SS, Dustin ML, McGavern DB. Myelomonocytic cell recruitment causes fatal CNS vascular injury during acute viral meningitis. Nature 2009; 457:191–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8."Of men, not mice." Editorial. Nat Med 2013; 19:379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seok J, Warren HS, Cuenca AG, et al. Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110:3507–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zinkernagel RM. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus and immunology. Curr Topics Microbiol Immunol 2002; 263:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oldstone MB. Biology and pathogenesis of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2002; 263:83–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zajac AJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, et al. Viral immune evasion due to persistence of activated T cells without effector function. J Exp Med 1998; 188:2205–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oldstone MBA, Habel K, Dixon FJ. The pathogenesis of cellular injury associated with persistent LCM viral infection. Fed Proc 1969; 28:429. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lundstedt C. Interaction between antigenically different cells: Virus-induced cytotoxicity by immune lymphoid cells in vitro. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1969; 75:139–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cole GA, Nathanson N, Prendergast RA. Requirement for theta-bearing cells in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-induced central nervous system disease. Nature 1972; 238:335–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zinkernagel RM, Doherty PC. Restriction of in vitro T cell-mediated cytotoxicity in lymphocytic choriomeningitis within a syngeneic or semiallogeneic system. Nature 1974; 248:701–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oldstone MBA, Blount P, Southern PJ, Lampert PW. Cytoimmunotherapy for persistent virus infection reveals a unique clearance pattern from the central nervous system. Nature 1986; 321:239–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brooks DG, McGavern DB, Oldstone MBA. Reprogramming of antiviral T cells prevents inactivation and restores T cell activity during persistent viral infection. J Clin Invest 2006; 116:1675–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wherry EJ. T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol 2011; 12:492–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, et al. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature 2006; 439:682–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brooks DG, Trifilo MJ, Edelmann KH, Teyton L, McGavern DB, Oldstone MBA. Interleukin-10 determines viral clearance or persistence in vivo. Nat Med 2006; 12:1301–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ejrnaes M, Filippi CM, Martinic MM, et al. Resolution of a chronic viral infection after interleukin-10 receptor blockade. J Exp Med 2006; 203:2461–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elsaesser H, Sauer K, Brooks DG. IL-21 is required to control chronic viral infection. Science 2009; 324:1569–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi JS, Du M, Zajac AJ. A vital role for interleukin-21 in the control of a chronic viral infection. Science 2009; 324:1572–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng CT, Oldstone MBA. Infected CD8α- dendritic cells are the predominant source of IL-10 during establishment of persistent viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:14116–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooks DG, Lee AM, Elsaesser H, McGavern DG, Oldstone MBA. IL-10 blockade facilitates DNA vaccine-induced T cell responses and enhances clearance of persistent virus infection. J Exp Med 2008; 205:533–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crawford A, Wherry EJ. The diversity of costimulatory and inhibitory receptor pathways and the regulation of antiviral T cell responses. Curr Opin Immunol 2009; 21:179–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brockman MA, Kwon DS, Tighe DP, et al. IL-10 is up-regulated in multiple cell types during viremic HIV infection and reversibly inhibits virus-specific T cells. Blood 2009; 114:346–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alter G, Kavanagh D, Rihn S, et al. IL-10 induces aberrant deletion of dendritic cells by natural killer cells in the context of HIV infection. J Clin Invest 2010; 120:1905–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flynn JK, Dore GJ, Hellard M, et al. Early IL-10 predominant responses are associated with progression to chronic hepatitis C virus infection in injecting drug users. J Viral Hepat 2011; 18:549–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das A, Ellis G, Pallant C, et al. IL-10-producing regulatory B cells in the pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Immunol 2012; 189:3925–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Day CL, Kaufmann DE, Kiepiela P, et al. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature 2006; 443:350–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watanabe T, Bertoletti A, Tanoto TA. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and T-cell exhaustion in chronic hepatitis virus infection. J Viral Hepat 2010; 17:453–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Penna A, Pilli M, Zerbini A, et al. Dysfunction and functional restoration of HCV-specific CD8 responses in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 2007; 45:588–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boni C, Fisicaro P, Valdatta C, et al. Characterization of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-specific T-cell dysfunction in chronic HBV infection. J Virol 2007; 81:4215–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brooks DG, Ha SJ, Elsaesser H, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ, Oldstone MBA. IL-10 and PD-L1 operate through distinct pathways to suppress T-cell activity during persistent viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105:20428–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan BM, Emonet SF, Welch MJ, et al. Point mutation in the glycoprotein of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus is necessary for receptor binding, dendritic cell infection, and long-term persistence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:2969–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee AM, Cruite J, Welch MJ, Sullivan B, Oldstone MBA. Pathogenesis of Lassa fever virus infection: I. Susceptibility of mice to recombinant Lassa Gp/LCMV chimeric virus. Virology 2013; 442:114–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bergthaler A, Flatz L, Hegazy AN, et al. Viral replicative capacity is the primary determinant of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus persistence and immunosuppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:21641–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sevilla N, Kunz S, Holz A, et al. Immunosuppression and resultant viral persistence by specific viral targeting of dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2000; 192:1249–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sevilla N, McGavern DB, Teng C, Kunz S, Oldstone MBA. Viral targeting of hematopoietic progenitors and inhibition of DC maturation as a dual strategy for immune subversion. J Clin Invest 2004; 113:737–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kunz S, Sevilla N, McGavern DB, Campbell KP, Oldstone MBA. Molecular analysis of the interaction of LCMV with its cellular receptor [alpha]-dystroglycan. J Cell Biol 2001; 155:301–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]