Abstract

The present study examined differences in lifetime use and initiation of substance use and associated risk factors for alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana among seven subgroups of Asian American (AA) adolescents: Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Mixed heritage Asian. Sixth and 7th grade AA adolescents in Southern California were surveyed five times over three academic years. We examined subgroup differences in (1) lifetime alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use assessed at baseline, (2) initiation of each substance over three years, and (3) baseline individual (positive and negative expectancies about substances, resistance self-efficacy, and intentions to use), family (closest adult and older sibling substance use), and school factors (perceived peer use). Although there was considerable heterogeneity in lifetime substance use and initiation rates, subgroup differences were not statistically significant (ps > .20). Significant subgroup differences existed for negative expectancies about use, perceived peer use, and close adult alcohol and cigarette use (ps < .05). Specifically, Vietnamese and Japanese adolescents had the lowest negative expectancies about cigarettes and marijuana, respectively. Vietnamese adolescents reported the highest levels of perceived peer cigarette use. Mixed-heritage adolescents reported the highest frequency of alcohol and cigarette use by their closest adult. Although no differences in substance use rates were observed, these findings are an important first step in understanding heterogeneity in AA adolescents’ risk for substance use and initiation.

Keywords: Asian, substance use, initiation, family substance use, perceived peer use, expectancies

Differences in Substance Use and Substance Use Risk Factors by Asian Subgroups

There are large racial/ethnic disparities in the rates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use in the United States. Typically, Asian American (AA) adolescents (e.g., American youth identifying with Asian ethnicities) report lower rates of substance use compared to other ethnic groups such as non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, and Hispanics (Bachman et al., 1991; Best et al., 2001; D'Amico et al., 2012; Grunbaum, Lowry, Kann, & Pateman, 2000; Rodham, Hawton, Evans, & Weatherall, 2005; Shih, Miles, Tucker, Zhou, & D'Amico, 2010; Wallace et al., 2002; Wallace et al., 2009). For instance, among youth ages 12–17 responding to the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 35.8% of non-Hispanic Whites, 31.6% of non-Hispanic Blacks, 34.6% of Hispanics, and 23.1% of Asians reported any alcohol use in their lifetime (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2011a). Lifetime cigarette use rates among youth ages 12–17 were 21.2%, 14.4%, 17.2%, and 10.5% for non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians, respectively (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2011b). Lifetime marijuana use among youth ages 12–17 were 17.1%, 17.7%, 18.9%, and 9.0% for non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians, respectively (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2011c).

However, although AA adolescents on average have the lowest prevalence rates of substance use, concern about substance use among AA adolescents is growing (Hahm, Wong, Huang, Ozonoff, & Lee, 2008; Lee, Battle, Lipton, & Soller, 2010; Thai, 2010). In addition, many epidemiological studies of adolescent substance use tend to group AAs together into one category, which hinders examination of the social, biological, and cultural factors that may contribute to the heterogeneity in risk for substance use by AA subgroups. For instance, these studies take a larger ethnic group (e.g., “Asian Americans”) and generalize drinking patterns across diverse subgroups (e.g., Japanese, Korean, Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese) when in fact drinking varies considerably between these subgroups (Lum, Corliss, Mays, Cochran, & Lui, 2009; Wong, Klingle, & Price, 2004). Failure to consider variation in substance use across AA subgroups not only neglects potential heterogeneity, but may also underestimate true prevalence rates of substance use and initiation among AAs (Hendershot, Dillworth, Neighbors, & George, 2008; Hendershot, MacPherson, Myers, Carr, & Wall, 2005; Wong, et al., 2004).

Lifetime and Past Month Substance Use by Asian American Subgroups

Studies that do disaggregate AA subgroups generally examine young adult populations such as college students, or adolescents that span a wide age range (Duranceaux et al., 2008; Hendershot et al., 2009; Hendershot, et al., 2005; Luczak, Wall, Cook, Shea, & Carr, 2004; Myers, Doran, Trinidad, Wall, & Klonoff, 2009). In general, these studies report extensive variability in rates of use with Korean-American students reporting higher rates of alcohol use disorders (13%) compared to Chinese-American students (5%) (Duranceaux, et al., 2008; Hendershot, et al., 2009; Hendershot, et al., 2005; Luczak, et al., 2004; Myers, et al., 2009). Other studies of high school adolescents find that the rates of past month alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use are highest among Filipino adolescents and lowest among Chinese adolescents (Harachi, Catalano, Kim, & Choi, 2001; Otsuki, 2003; Price, Risk, Wong, & Klingle, 2002; Wong, et al., 2004). One study that included younger Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, and Korean adolescents (ages 12–18) in California (Chen, Unger, Cruz, & Johnson, 1999) found that Filipino adolescents reported the highest rates of lifetime smoking (18.9%) and past month smoking (8.6%), whereas Chinese adolescents reported the lowest rates of lifetime smoking (11.0%) and past month smoking (2.8%). To complement this study on smoking, two studies have examined alcohol and marijuana use among 12–17 year old adolescents identifying with Japanese, Filipino, Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese ethnicities in one wave of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), a longitudinal study of a nationally representative sample of adolescents in grades 7–12 in the United States (Choi, 2008; Price, et al., 2002). Contrary to other studies, these two papers reported that Japanese adolescents had the highest rates of past year alcohol use (36.0%) and any lifetime marijuana use (31.6%). Mixed-heritage AA and Pacific Islanders in the Add Health study were also at higher risk for any type of substance use in comparison to unmixed-heritage adolescents of the same AA and Pacific Islander subgroups (e.g., mixed heritage Vietnamese adolescents were more likely to use substances than Vietnamese adolescents without mixed heritage), even after controlling for foreign-born status, speaking native language at home, immigration timing, and socioeconomic measures (Choi, 2008; Price, et al., 2002).

In sum, while prior studies on disaggregated AA subgroups provide valuable information about lifetime substance use rates, only a handful of studies have examined more than five subgroups beyond Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Filipinos (Chen, et al., 1999; Lee, et al., 2010), and have found discrepant findings in terms of which AA subgroup reported the highest rates of lifetime substance use. These studies also include a wide age range of adolescents and no studies to our knowledge have solely examined younger adolescents, a group at highest risk for substance use initiation (D'Amico et al., 2005b; Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2008; Wittchen et al., 2008).

Substance Use Initiation by Asian American Subgroups

Substance use initiation is important to examine because earlier initiation of substances increases the risk for use of illicit drugs, alcohol and other drug use disorders (Dawson, Goldstein, Chou, Ruan, & Grant, 2008; King & Chassin, 2007), low academic intentions (Ellickson, Tucker, Klein, & Saner, 2004; Warner & White, 2003), antisocial behavior (Krueger et al., 2002; McGue, Iacono, & Krueger, 2006), and has potential long term consequences for neurological development (Padula, Schweinsburg, & Tapert, 2007; Schweinsburg, Brown, & Tapert, 2008; Spear, 2000). Existing studies of substance use initiation among disaggregated AA subgroups focus exclusively on smoking initiation for cigarettes. For example, Chen & Unger (1999) examined rates of smoking initiation among AA adolescents ages 12–17 and found that there were large differences in the risk for initiation by AA subgroup such that Chinese adolescents had the lowest risk of smoking initiation whereas Filipino adolescents had the highest risk of initiation. The Minority Youth Health project in Seattle examined smoking initiation among AA in grades 6–8th and found similar AA subgroup differences in smoking initiation (Harachi, et al., 2001). Although these studies provide valuable information on the heterogeneity in risk for smoking initiation, there is growing concern about heavy drinking among AA adolescents (Hahm, Lahiff, & Guterman, 2003; Hahm, et al., 2008). Early use of any substance has been linked with increased heavy drinking in later adolescence regardless of race/ethnicity (LaBrie, Rodrigues, Schiffman, & Tawalbeh, 2007). Thus, it is important to characterize early initiation of not only smoking, but also other substances such as alcohol and marijuana in AA subgroups. The current study will be the first to examine longitudinal data on initiation of more than one substance among AA middle school adolescents.

Differences in Risk and Protective Factors by Asian American Subgroups

The observation that AA youth have lower rates of substance use compared to non-Hispanic White and Black adolescents has been attributed to protective factors such as lower adult and peer substance use, less access to substances, lower intentions to use substances, and higher academic performance (Gillmore et al., 1990; Landrine, Richardson, Klonoff, & Flay, 1994; Wall, Shea, Chan, & Carr, 2001).

Some studies report that non-Hispanic Black adolescents have higher rates of both negative and positive expectancies or beliefs about alcohol compared to non-Hispanic White adolescents (Hipwell et al., 2005; Meier, Slutske, Arndt, & Cadoret, 2007), although others have reported no differences (Rinehart, Bridges, & Sigelman, 2006). In addition, Oei & Jardim (2007) found that White college students reported more positive expectancies and less resistance self-efficacy for alcohol (the ability to refuse alcohol) compared to Asians. Other family risk factors such as older sibling use and adult usse are related to risk for substance use, and our prior work (Shih, et al., 2010) suggests that these factors help explain racial/ethnic disparities in lifetime alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. In addition to these individual cognitive and family risk factors, intentions to use and perceived use by peers have been linked with substance use. Non-Hispanic White and Hispanic adolescents generally report greater perceptions of peer substance use compared to other ethnicities (D'Amico & McCarthy, 2006; Juvonen, Martino, Ellickson, & Longshore, 2001). Intentions to use also frequently differ by race such that in one study of urban youth, Whites were more likely to report higher intentions to use drugs than Black or Asian youth, although perceived use by peers did not differ by race in this study (Gillmore, et al., 1990).

Despite this robust literature on differences in risk and protective factors for racial/ethnic groups, only one published study has examined whether there are differences in the extent to which individual, family, and school risk factors may influence substance use among disaggregated AA subgroups. Thai and colleagues (2010) examined the influence of acculturation, peer substance use, and academic achievement on any lifetime alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use among six AA subgroups in Add Health (n = 1,248). After accounting for these factors, there were no differences in risk of lifetime alcohol, cigarette, or marijuana use by AA subgroup, although Vietnamese adolescents did have lower rates of marijuana use even after accounting for all three factors.

Our work builds on this study and significantly extends research in this area by longitudinally assessing a large sample of AAs and examining a host of risk and protective factors that have been linked with lifetime use and initiation of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana, including age (Glanz, Maskarinec, & Carlin, 2005; Kaplan et al., 2003), sex (Sasao, 1999), positive and negative expectancies (Barkin, Smith, & DuRant, 2002; Elder et al., 2000; Spruijt-Metz, Gallaher, Unger, & Johnson, 2005), resistance self-efficacy or ability to resist offers to use substances (D'Amico & McCarthy, 2006; Oei & Burrow, 2000; Oei, Fergusson, & Lee, 1998; Oei & Morawska, 2004; Olds, Thombs, & Tomasek, 2005; Orlando, Ellickson, McCaffrey, & Longshore, 2005), close adult and older sibling substance use (Unger & Chen, 1999; Wiecha, 1996), intentions to use (Andrews, Tildesley, Hops, Duncan, & Severson, 2003), and perceived use among peers at school (Chi, Lubben, & Kitano, 1989; Newcomb & Bentler, 1986; Unger et al., 2001). Although prior studies that use cross-sectional Add Health data from the 1994–95 school year have contributed substantially to understanding AA heterogeneity in substance use (Price, et al., 2002; Thai, et al., 2010), the present study extends this literature in several ways. First, we expand the research on AA adolescent substance use prevalence and initiation rates by utilizing more recently collected, longitudinal data on both lifetime substance use and substance use initiation in a younger sample. In addition, contrary to many other studies of AA adolescents that examine “Asian Americans” as a homogeneous group, we examine differences among seven of the largest AA subgroups that comprise more than 90% of AA and Pacific Islanders in the U.S. (Reeves & Bennett, 2004), with comparable proportions in each AA subgroup to Add Health. We also explore whether there are differences by AA subgroup in individual, family, and school factors that may be influential in adolescents’ risk for substance use and initiation. Because no other study has examined such a young adolescent sample with so many AA subgroups, the goal of this exploratory study is to conduct hypothesis-generating analyses to determine which AA subgroups may be at greater or reduced risk for lifetime substance use and initiation, and to determine the factors that may be most promising to target in early interventions for AA youth.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The analytic sample is comprised of 6th and 7th grade students in 16 middle schools across three school districts in Southern California who participated in the evaluation of CHOICE, a voluntary after-school prevention program targeting alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette use (D'Amico, et al., 2012). This paper presents secondary data analyses on five waves of surveys covering three academic years from 6th – 7th grade through 8th – 9th grades. The self-administered surveys were completed in school during PE class and took approximately 45 minutes to complete. The baseline Wave 1 survey was completed in Fall 2008, and the Wave 2 survey in Spring 2009. Waves 3 (Fall 2009) and Wave 4 (Spring 2010) took place during the second academic year, and Wave 5 (Spring 2011) took place during the third academic year. Schools were compensated on a sliding scale determined by the percentage of returned consent forms (regardless of whether the parent responded “yes” or “no”) with a maximum of $2500 compensation per school per wave. Survey responses were protected by a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health. All materials and procedures were approved by the school districts, individual schools, and the institution’s Internal Review Board.

At baseline, 14,979 students were approached for parental consent, with consent forms provided in English, Spanish, or Korean. Ninety-two percent (13,785) returned a consent form with approximately 71% (9,828) providing consent to participate. The number of valid surveys completed at Wave 1 (8,932, or 91% of those consented) was higher or comparable to other school-based survey completion rates with this population (Johnson & Hoffmann, 2000; Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2009; Kandel, Kiros, Schaffran, & Hu, 2004). Because 8th graders at Wave 1 were not followed after leaving their middle schools during the next school year and did not contribute to Waves 3–5, we focus on the 6th and 7th graders at Wave 1 (5,839) who were followed until they were 8th and 9th graders in Wave 5.

Across the 16 schools, N = 5,839 6th and 7th grade students at Wave 1 were followed through 8th and 9th grade in Wave 5. Of these students, n = 953 students self-identified as AA and did not indicate that any other racial/ethnic group described them. We excluded a total of 52 Cambodian, Laotian, and other Asian adolescents because of the small number of adolescents in each of these subgroups, yielding an analytic sample of n = 901 AAs which included Chinese (109), Filipinos (149), Indians (45), Japanese (217), Korean (189), Vietnamese (55), and mixed heritage Asian (137) subgroups. Out of the 137 mixed heritage Asians, the most frequently selected combinations were Chinese/Japanese (18), Chinese/Filipino (13), Japanese/Korean (11), Chinese/Other (11), and Chinese/Vietnamese (11). Among the 901 Asian Americans who filled out the baseline survey, follow-up rates from wave to wave ranged from 78% to 97%. This is the first paper from the CHOICE project to analyze the Asian American subset of all CHOICE participants.

Measures

Baseline Socio-demographic Characteristics

The survey asked students about their age, sex, grade-level and race/ethnicity at baseline. Respondents initially classified themselves by ethnicity (Hispanic or not Hispanic) and were then asked about their race (US DHHS, 2001). To assess AA subgroups, respondents were asked “If you are Asian or Pacific Islander, which groups best describe you?” Respondents could answer one or more categories of Chinese; Filipino; Japanese; Korean; Vietnamese; Asian Indian; Cambodian; Laotian; Native Hawaiian, Guamanian, Samoan, or other Pacific Islander; and Other Asian.

Alcohol, Cigarette, and Marijuana Use and Initiation

Lifetime frequency of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use was assessed using well-established measures from the California Healthy Kids Survey (WestEd, 2008) and Project ALERT (Ellickson, McCaffrey, Ghosh-Dastidar, & Longshore, 2003). Lifetime use was assessed by asking “During your life, how many times have you used or tried [a cigarette/one full drink/marijuana]?” A “drink” was defined as one whole drink of alcohol (not including few sips of a drink, such as wine for religious purposes). Cigarette use was defined as “a cigarette, even one or two puffs.” Variability in responses for higher frequency of consumption in this young population was very low. Therefore, for analytic purposes, respondents were classified into dichotomous categories of any lifetime use (one time or more) and no lifetime use (never used the substance).

If lifetime use was endorsed as “yes” in a prior wave, we logically imputed the lifetime use variable for that student in subsequent waves to be “yes.” The rate of imputed cases was low (1.3–6.8%) across the three substances. We defined initiation between waves (e.g., Wave 1 to Wave 2) as reporting any lifetime use in the subsequent survey where there was no lifetime use reported in the survey at the prior wave. We created separate outcome variables for initiation of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana from Wave 1 to Wave 5.

Baseline Individual Factors

For each of the three substances we assessed positive and negative expectancies and resistance self-efficacy (RSE). We measured positive and negative expectancies about each substance’s effects using separate six-item scales for alcohol, cigarette and marijuana (Ellickson, et al., 2003). For example, alcohol and marijuana positive expectancy items asked whether students thought that using the substance would relax them or let them have more fun. Alcohol and marijuana negative expectancies asked whether students thought that using the substance would make them do poorly in school, or make them do things they might regret. Cigarette positive and negative expectancies were assessed by asking, for example, whether students thought that cigarettes would help them stay thin or make other people not want to be around them. Students indicated their extent of agreement with each statement using a fourpoint response scale (1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree) and responses were averaged (Cronbach’s alphas for the positive and negative scales for each of the three substances ranged from 0.75 to 0.87). Scores for negative expectancies were reverse coded so that higher scores indicated higher positive or higher negative expectancies.

Resistance self-efficacy for each substance was assessed by asking students three questions for each substance: “Suppose you are offered alcohol [or marijuana or cigarettes] and you do not want to use it [them]. What would you do in these situations: A) your best friend is drinking alcohol [smoking cigarettes/using marijuana); B) you are bored at a party; and C) all your friends at a party are drinking alcohol [smoking cigarettes/using marijuana]” (Ellickson, et al., 2003). These three items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 = “I would definitely drink/smoke cigarettes/use marijuana” to 4 = “I would definitely not drink/smoke cigarettes/use marijuana” and then averaged to develop a single RSE scale for each of the three substances (Cronbach’s alphas for the three scales ranged from 0.93 to 0.96). Higher scores indicated higher RSE.

Intention to use a substance was assessed by asking students “Do you think you will use drink any alcohol [smoke a cigarette/use any marijuana] in the next six months?” The response categories were 1 = “definitely yes,” 2 = “probably yes,” 3 = “probably no,” and 4 = “definitely no.” We reverse coded these scores so that higher scores indicated stronger intention to use.

Baseline Family Factors

Family substance use was assessed by asking students how often the adult most important to them that they spend time with used alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana. Response options were 1 = “never,” 2 = “less than once a week,” 3 = “1–3 days a week,” and 4 = “4–7 days a week.” Due to infrequency of students’ reporting of the top three category responses, we dichotomized this item so that the three top categories were collapsed to represent an affirmative response (1) and ‘never” was set to 0 (no close adult use). Students were also asked if any of their older siblings used each specific substance (yes/no). If students did not have any older siblings, they were classified as missing.

Baseline School Factors

Perceived use among peers at school was measured using a question derived from the California Healthy Kids Survey. Respondents were asked approximately how many students in 100 have drunk alcohol at least once a month [smoked cigarettes at least once a month/ever tried marijuana] (WestEd, 2008). Response options ranged from 0 to 100 with multiples of 10 as anchors. Responses were recoded to percentages (e.g., reported perception of use by 20 students out of 100 was converted to 20%).

Data Analyses

We report unadjusted rates (i.e., no adjustment for covariates such as age or sex) of lifetime use and initiation for alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana by AA subgroup. We also explored differences in the individual, family, and school factors by AA subgroup. All comparisons by AA subgroup were tested using a chi-square test for dichotomous variables and ANOVA for continuous variables.

Results

Baseline Risk/Protective Factors, Overall and by Asian American Subgroup

As shown in Table 1, the sample of 901 AAs was 50% male and had a mean age of 11.5 years at baseline (SD = 0.65). Negative expectancies for the whole sample were fairly high on the scale of 1–4 (3.2 for alcohol; 3.3 for cigarettes and marijuana) and positive expectancies were low (1.3 for alcohol and cigarettes; 1.2 for marijuana). On a scale of 1–4, RSE was high for all three substances (3.8 for alcohol; 3.9 for cigarettes and marijuana) and intentions to use substances were low (1.3 for alcohol and marijuana; 1.2 for cigarettes). Most adolescents reported infrequent substance use for the adult most important to them, and older sibling use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana was reported by only 9.6%, 4.8% and 1.5% of adolescents who had an older sibling, respectively. Perceptions of substance use among school peers were also fairly low (1.5–3.2% of students).

Table 1.

Baseline Risk and Protective factors by Asian American (AA) Subgroup, Mean (SD) or N (%)

| Chinese (n = 109) |

Filipino (n = 149) |

Indian (n = 45) |

Japanese (n = 217) |

Korean (n = 189) |

Vietnamese (n = 55) |

Mixed heritage Asian (n = 137) |

Total AAs (n = 901) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, N (%) | 52 (47.71) | 77 (51.68) | 21 (46.67) | 111 (51.39) | 101 (53.44) | 27 (49.09) | 61 (44.53) | 450 (50.06) | .768 |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 11.40 (0.64) | 11.52 (0.63) | 11.27 (0.69) | 11.50 (0.62) | 11.44 (0.72) | 11.45 (0.60) | 11.42 (0.64) | 11.45 (0.65) | .320 |

| Negative expectancies, mean (SD) | |||||||||

| Alcohol | 3.40 (0.84) | 3.04 (1.02) | 3.26 (0.91) | 3.13 (1.04) | 3.11 (1.03) | 3.18 (0.91) | 3.18 (0.97) | 3.16 (0.99) | .144 |

| Cigarettes | 3.54 (0.80) | 3.22 (1.09) | 3.44 (0.94) | 3.16 (1.06) | 3.25 (1.06) | 2.96 (1.17) | 3.44 (0.91) | 3.28 (1.03) | .003 |

| Marijuana | 3.51 (0.87) | 3.17 (1.06) | 3.31 (1.02) | 3.11 (1.16) | 3.17 (1.09) | 3.28 (1.03) | 3.40 (0.92) | 3.25 (1.05) | .018 |

| Positive expectancies, mean (SD) | |||||||||

| Alcohol | 1.20 (0.49) | 1.29 (0.59) | 1.33 (0.67) | 1.34 (0.65) | 1.32 (0.64) | 1.28 (0.59) | 1.28 (0.58) | 1.30 (0.60) | .634 |

| Cigarettes | 1.23 (0.40) | 1.30 (0.52) | 1.35 (0.64) | 1.29 (0.55) | 1.31 (0.58) | 1.39 (0.64) | 1.27 (0.47) | 1.29 (0.54) | .657 |

| Marijuana | 1.12 (0.36) | 1.23 (0.53) | 1.29 (0.69) | 1.24 (0.55) | 1.18 (0.49) | 1.29 (0.71) | 1.23 (0.50) | 1.21 (0.53) | .322 |

| Resistance self-efficacy, mean (SD) | |||||||||

| Alcohol | 3.88 (0.38) | 3.78 (0.52) | 3.78 (0.67) | 3.86 (0.39) | 3.86 (0.40) | 3.70 (0.67) | 3.88 (0.35) | 3.84 (0.45) | .068 |

| Cigarettes | 3.94 (0.30) | 3.84 (0.56) | 3.95 (0.31) | 3.91 (0.36) | 3.93 (0.33) | 3.84 (0.60) | 3.93 (0.36) | 3.91 (0.40) | .261 |

| Marijuana | 3.98 (0.14) | 3.86 (0.57) | 3.94 (0.30) | 3.92 (0.40) | 3.89 (0.44) | 3.85 (0.59) | 3.88 (0.49) | 3.90 (0.45) | .400 |

| Intentions to use, mean (SD) | |||||||||

| Alcohol | 1.17 (0.55) | 1.34 (0.85) | 1.20 (0.76) | 1.25 (0.74) | 1.36 (0.90) | 1.53 (1.02) | 1.29 (0.76) | 1.30 (0.80) | .111 |

| Cigarettes | 1.23 (0.76) | 1.16 (0.66) | 1.07 (0.46) | 1.21 (0.76) | 1.18 (0.70) | 1.30 (0.89) | 1.38 (0.96) | 1.22 (0.76) | .150 |

| Marijuana | 1.31 (0.91) | 1.26 (0.79) | 1.07 (0.46) | 1.32 (0.92) | 1.35 (0.96) | 1.22 (0.79) | 1.27 (0.84) | 1.29 (0.87) | .598 |

| Closest adult uses, N (%) | |||||||||

| Alcohol | 32 (32.65) | 47 (36.15) | 6 (15.38) | 90 (46.63) | 81 (46.02) | 45 (36.29) | 24 (50.00) | 325 (40.22) | .001 |

| Cigarettes | 12 (12.12) | 26 (19.70) | 1 (2.56) | 33 (17.01) | 42 (23.73) | 26 (20.80) | 15 (31.25) | 155 (19.04) | .006 |

| Marijuana | 1 (1.02) | 4 (3.03) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.54) | 4 (2.26) | 1 (0.81) | 1 (2.08) | 14 (1.73) | .776 |

| Older sibling uses, N (%) | |||||||||

| Alcohol | 4 (7.02) | 13 (16.05) | 0 (0) | 7 (6.36) | 12 (11.11) | 3 (8.82) | 7 (9.33) | 46 (9.56) | .332 |

| Cigarettes | 1 (1.75) | 8 (9.76) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.82) | 5 (4.63) | 4 (11.76) | 3 (4.17) | 23 (4.80) | .077 |

| Marijuana | 1 (1.75) | 3 (3.75) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.85) | 1 (3.03) | 0 (0) | 7 (1.47) | .242 |

| Perceived peer use, mean out of 100% (SD) | |||||||||

| Alcohol | 3.07 (7.03) | 4.60 (10.50) | 4.25 (10.59) | 2.61 (7.67) | 2.85 (7.51) | 3.40 (7.06) | 2.50 (6.64) | 3.15 (8.09) | .308 |

| Cigarettes | 1.78 (5.18) | 3.14 (7.05) | 1.75 (5.49) | 1.36 (5.29) | 1.34 (4.29) | 5.28 (16.01) | 2.02 (6.17) | 2.06 (6.78) | .003 |

| Marijuana | 1.39 (4.01) | 2.65 (7.91) | 0.75 (2.67) | 1.41 (5.95) | 1.47 (6.40) | 0.96 (2.98) | 1.56 (5.81) | 1.58 (5.96) | .419 |

Notes: p value from ANOVA for continuous variables and Fishers Exact Test or Chi-squared Test for categorical variables. Denominators do not add up to total baseline subgroup sizes because of missing data on some items. Expectancies and resistance self-efficacy range from 1–4. Perceived use among peers at school ranged 0–100% such that if a student reported 20 students out of 100 used a substance, it was converted to 20%. Substance use by closest adult was coded dichotomously, never vs. “less than once/week,” or “1–3 days/week,” or 4 = “4–7 days/week.” Older sibling use was reported among students with an older sibling; those without an older sibling were coded as missing. Bolded values indicate p ≤ .05.

Tests of differences by AA subgroup for risk and protective factors showed that negative expectancies about cigarette (F = 3.38; df = 6; p = .003) and marijuana use (F = 2.57; df = 6; p = .018) significantly differed by subgroup, but negative expectancies about alcohol use did not differ (p = .144). Chinese adolescents reported the highest negative expectancies for cigarette and marijuana use, whereas Vietnamese adolescents reported the lowest negative expectancies for cigarette use, and Japanese adolescents reported the lowest negative expectancies for marijuana use. No statistically significant differences in positive expectancies, RSE, or intentions to use were observed (all ps > .05).

There were significant differences in reports of adult use of alcohol (χ2 = 21.70; df = 6; p = .001) and cigarettes (χ2 = 17.91; df = 6; p = .004), but not marijuana (χ2 = 3.26; df = 6; p = .776). Mixed-heritage adolescents reported the highest adult use of alcohol and cigarettes, and Indian adolescents reported the lowest adult use of both substances.

Perceived peer use of cigarettes differed by subgroup (F = 3.36; df = 6; p = .003), but perceived peer use of alcohol and marijuana did not (F = 1.19; df = 6; p = .308 and F = 1.01; df = 6; p = .419, respectively). Perceived peer use of cigarettes was highest among Vietnamese adolescents and lowest among Korean adolescents.

Lifetime Substance Use by Asian American Subgroup

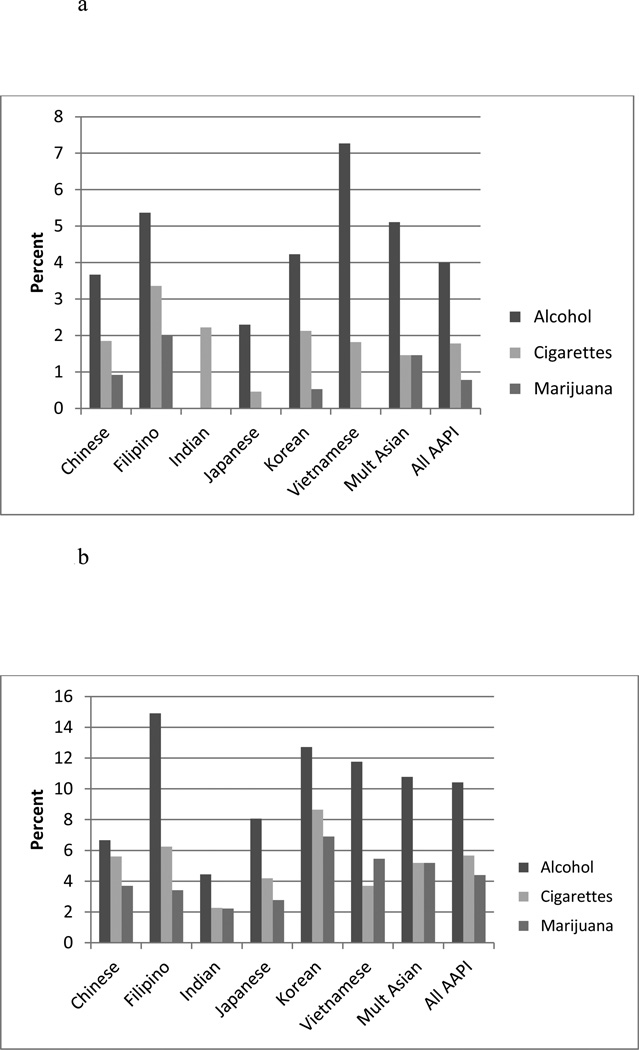

Figure 1a depicts lifetime alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use at baseline for all the subgroups. Overall, lifetime rates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use among AAs were 4.0%, 1.8%, and 0.8%, respectively. We did not find any statistically significant differences in lifetime rates of alcohol, cigarette, or marijuana use by AA subgroup (all ps > .05). However, it is important to note trends in rates of lifetime substance use by subgroup. Vietnamese adolescents reported the highest rates of lifetime alcohol use (7.3%), whereas Japanese adolescents reported the lowest lifetime rate of alcohol use (2.3%). For lifetime cigarette and marijuana use, Filipino adolescents reported the highest rates at 3.4% and 2.0%, respectively. Again, Japanese youth reported the lowest lifetime rate (0.5%) of cigarette use and both Japanese and Indian adolescents reported the lowest lifetime rate (0%) of marijuana use.

Figure 1.

a Lifetime Substance Use by Asian American Pacific Islander Subgroup (n = 901)

b Substance Use Initiation Over 3 Academic Years by Asian American Pacific Islander Subgroup (n = 901)

Note: Percentages do not sum across rows because of different sample sizes at each wave.

Substance Use Initiation by Asian American Subgroup

Figure 1b shows initiation rates of the three substances from Wave 1 to Wave 5. Although subgroup differences in initiation rates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use were not statistically significant (all ps > .05), we note a few trends in initiation rates by sub-group. Initiation of alcohol use over the five waves of data was highest for Filipino (14.9%) and Korean (12.7%) adolescents and lowest for Indian adolescents (4.4%). For cigarette use initiation, rates were highest among Korean (8.7%) and Filipino (6.3%) adolescents and lowest among Indian adolescents (2.3%). For marijuana initiation, rates were highest among Korean (6.9%) and Vietnamese (5.5%) adolescents and lowest among Indian adolescents (2.2%).

Discussion

Most of the published literature on substance use among AAs has examined risk among this broad but diverse group as a homogeneous population. However, research must acknowledge the heterogeneity of substance use among subgroups to efficiently direct resources to reduce disparities in adolescent substance use. This study is the first to examine rates of use among seven different subgroups of younger AA adolescents. Overall, lifetime rates of alcohol, cigarette and marijuana were low for all subgroups, which is a typical finding for younger adolescent populations and for younger AA populations in particular (Chen & Unger, 1999; Otsuki, 2003).

Although we did not find statistically significant differences, we observed considerable heterogeneity in lifetime substance use and initiation rates by AA subgroup. We did not conduct two-group comparisons; however, examination of the percentages suggests that Vietnamese adolescents appeared to be more than three times as likely to report lifetime alcohol use at baseline compared to Japanese adolescents, and Filipino adolescents appeared to be seven times as likely to report cigarette use at baseline compared to Japanese adolescents. Korean adolescents appeared to be about three times as likely as Indian adolescents to initiate alcohol, cigarette, or marijuana use over a 3-year period, although again, no two-group comparisons were conducted. Although not significant, these differences suggest that tracking substance use and initiation over time among a larger sample of AAs is important and may help identify subgroups at highest risk for substance use initiation in early adolescence.

We also found heterogeneity by AA subgroups across substances, although it is important to emphasize that we did not find statistically significant differences by subgroup. Some interesting trends observed were that Vietnamese adolescents reported the highest rates of lifetime alcohol use, but they reported a low rate of lifetime marijuana use. Filipino adolescents reported the highest rates of alcohol initiation, but had one of the lowest rates of marijuana initiation. Vietnamese adolescents had relatively high rates of alcohol and marijuana initiation, but one of the lowest rates of cigarette initiation, compared to other groups. By contrast, Korean adolescents reported some of the highest rates of initiation across all three substances. Future studies with larger AA subgroups should carefully consider whether certain subgroups exhibit a preference for using one or multiple substances in early adolescence. This research could indicate that targeted efforts are needed among at-risk subgroups with prevention messaging to prevent onset of specific substances.

Finding statistically significant differences was difficult because of low statistical power due to small sample sizes among each of the subgroups. Some other studies that included both middle school-aged and older AA adolescents (ages 12–18) have reported trends of differences by AA subgroup such that Filipino, Japanese, and multiethnic Asian adolescents reported higher rates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use (Chen, et al., 1999; Choi, 2008; Price, et al., 2002) than other AA subgroups. It may be that the conflicting results we observed in our study which did not find differences are due to the fact that those studies included older adolescents in their samples. It is difficult to examine heterogeneity in AA substance use and also have sufficiently large subgroup sizes to detect statistically significant differences. Nevertheless, our descriptive report is helpful in understanding rates of use among AA subgroups in early adolescence and paves the way for future longitudinal work with larger samples to understand whether rates of use and initiation over time may differ among AA subgroups.

Our study sought to clarify subgroup differences in early adolescence which may be able to assist with early prevention efforts for subgroups at highest risk for initiating substances. Initiation of cigarette smoking in particular is important to track among AA groups because certain AAs have high rates of cigarette use in young adulthood (e.g., 25% among Filipinos and 30% among Koreans ages 18–25 years) according to the U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (Benjamin, 2012). These rates suggest that smoking initiation among certain AAs may increase substantially throughout adolescence and into adulthood (Chen & Unger, 1999).

We also examined a host of individual, family, and school risk and protective factors by AA subgroup. Significant subgroup differences existed for negative expectancies about cigarette and marijuana use, close adult alcohol and cigarette use, and perceived peer use of cigarettes. Each of these factors are related to substance use in both AA and other adolescent racial/ethnic groups and may serve as early indicators for substance use risk during later adolescence. For example, Vietnamese and Filipino adolescents reported higher levels of perceived cigarette use among their peers. Given that this is associated with higher risk for cigarette initiation (D'Amico & McCarthy, 2006), targeting perceptions of peer use in early adolescence may be particularly beneficial for reducing risk of substance use among Vietnamese or Filipino subgroups. We also found that adult use of alcohol and cigarettes differed by AA subgroup such that mixed-heritage adolescents were more likely to report use by their important adult. The Add Health study, which included older adolescents than those in our sample, reported that mixed-heritage AA and Pacific Islanders were at higher risk for substance use in comparison to unmixed-heritage adolescents of the same AA and Pacific Islander subgroups. Thus, our finding suggests that targeting prevention efforts to very young adolescents who have a close adult that uses alcohol or cigarettes may be most beneficial for mixed-heritage adolescents. Family substance use is a risk factor for substance use in AA and other adolescent samples (Ary, Tildesley, Hops, & Andrews, 1993; D'Amico & Fromme, 1997; Komro, McCarty, Forster, Blaine, & Chen, 2003; Li, Pentz, & Chou, 2002; van der Vorst, Engels, Meeus, Dekovic, & Van Leeuwe, 2005; Windle, 2000). Thus, future research on larger, more statistically powered samples should examine whether AA differences in these family factors explain differences in AA substance use or initiation of substance use.

The strengths of our study include assessing the prevalence of alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette use among seven subgroups of young adolescent AAs and providing longitudinal data on initiation of alcohol, marijuana and cigarette use. Nevertheless, we note several limitations of our analyses. First, because of the small subgroup sample sizes, we did not examine adjusted prevalence rates or adjusted associations between the risk and protective factors and substance use or initiation. However, this study is an important first step in describing prevalence rates and risk and protective factors for seven AA subgroups and leads the way for future studies with more statistical power to examine adjusted associations between predictive factors and subsequent substance use and initiation. Second, we examined a group of AA adolescents in one region of the country only. Although nearly half of AAs live in the Western U.S. states, there are AA subgroup differences in region of residence (e.g., Indian adults are more equally distributed across the country compared to other AAs (Hoeffel, Rastogi, Kim, & Shahid, 2012; Taylor, 2012). Therefore, whereas our study afforded the opportunity to examine seven AA subgroups living in the racially/ethnically diverse Southern California region, this sample may not necessarily be representative of other AAs. Further, future studies of AA adolescents should aim to address other risk or protective factors associated with substance use and initiation among AAs such as self-esteem, depression, parental attitudes about substance use, and social norms regarding substance use by AA subgroups (Butters, 2004; Towberman & McDonald, 1993). In addition, studies could examine the role of acculturation among AAs. Higher acculturation to Western culture (often imperfectly measured by English language preference or generational status) is associated with higher risk of substance use among AA adolescents (Hahm, et al., 2003; Hussey et al., 2007). Acculturation levels may partially explain the patterns we observed since AA subgroups immigrated to different regions of the country and at different times in U.S. history and they and their offspring may therefore have varying levels of acculturation. In addition to measures of acculturation, cultural values such as ethnic identity, respect of parents, and stronger family ties may play a role in substance use. However, we previously did not find any significant differences in cultural factors by racial/ethnic categories in the larger overall sample of Hispanic, non-Hispanic Whites and Blacks, and Asian American and Pacific Islanders (Shih, et al., 2010). Furthermore, exploratory analyses among the AA subgroups in the current study revealed no significant differences, perhaps because this is a more acculturated, young sample of AAs.

It is also important to note that genetic factors may influence the level of response to substances. For example, the aldehyde dehydrogenase ALDH2*2 allele is found exclusively among individuals of northwest Asian heritage (Chinese, Korean, Japanese) and carriers typically report significantly lower rates of alcohol use compared to non-carriers (Duranceaux, et al., 2008; Luczak, Wall, Shea, Byun, & Carr, 2001; Wall, et al., 2001). Thus, genetic factors that influence responses to alcohol in particular, are correlated with AA subgroup membership. Future studies should account for genetic factors when examining AA subgroup differences in substance use and risk factors for substance use because they may partly explain differences.

In general, research has shown that AA youth are less likely to report use of alcohol, marijuana, and cigarettes than other racial/ethnic groups (Benjamin, 2012). Even though overall AA use was low in our young adolescent sample, findings indicate some heterogeneity in lifetime use and initiation of use among AA subgroups. This suggests the need to consider how to best focus prevention efforts for those at highest risk of initiation during middle school. AAs are typically underrepresented in nationally recognized evidence-based prevention programs (Le, Goebert, & Wallen, 2009; National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices, 2008). Our findings suggest that in order to reduce the potential for AA disparities in substance use from adolescence through adulthood, prevention programs must comprehensively address individual, family, and school risk factors in AAs such as having lower negative beliefs, greater rates of family substance use, and higher perceptions of peer use which may affect risk of substance initiation during this important developmental period.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA016577; “Brief Voluntary Alcohol and Drug Intervention for Middle School Youth”; Principal Investigator: Elizabeth J. D’Amico).

References

- Andrews JA, Tildesley E, Hops H, Duncan SC, Severson HH. Elementary school age children's future intentions and use of substances. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32(4):556–567. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ary DV, Tildesley E, Hops H, Andrews J. The influence of parent, sibling, and peer modeling and attitudes on adolescent use of alcohol. International Journal of the Addictions. 1993;28(9):853–880. doi: 10.3109/10826089309039661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Wallace JM, Jr, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Kurth CL, Neighbors HW. Racial/ethnic differences in smoking, drinking, and illicit drug use among American high school seniors, 1976–89. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81(3):372–377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkin SL, Smith KS, DuRant RH. Social skills and attitudes associated with substance use behaviors among young adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:448–454. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin RM. A new Surgeon General's report: Preventing tobacco use among adolescents and young adults. Public Health Reports. 2012;127(4):360–361. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best D, Rawaf S, Rowley J, Floyd K, Manning V, Strang J. Ethnic and gender differences in drinking and smoking among London adolescents. Ethnicity & Health. 2001;6(1):51–57. doi: 10.1080/13557850123660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butters JE. The impact of peers and social disapproval on high-risk cannabis use: Gender differences and implications for drug education. Drugs: Education Prevention and Policy. 2004;11(5):381–390. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Unger JB. Hazards of smoking initiation among Asian American and non-Asian adolescents in California: A survival model analysis. Preventive Medicine. 1999;28(6):589–599. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Unger JB, Cruz TB, Johnson CA. Smoking patterns of Asian-American youth in California and their relationship with acculturation. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24(5):321–328. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi I, Lubben JE, Kitano HH. Differences in drinking behavior among three Asian-American groups. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50(1):15–23. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y. Diversity within: Subgroup differences of youth problem behaviors among Asian Pacific Islander American adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36(3):352–370. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Ellickson PL, Wagner EF, Turrisi R, Fromme K, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Wright D. Developmental considerations for substance use interventions from middle school through college. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005b;29(3):474–483. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000156081.04560.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Fromme K. Health risk behaviors of adolescent and young adult siblings. Health Psychology. 1997;16(5):426–432. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.5.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, McCarthy DM. Escalation and initiation of younger adolescents' substance use: The impact of perceived peer use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39(4):481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Shih RA, Tucker JS, Miles JNV, Zhou AJ, Green HD., Jr Preventing alcohol use with a voluntary after school program for middle school students: Results from a cluster randomized controlled trial of CHOICE. Prevention Science. 2012;13(4):415–425. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0269-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Grant BF. Age at first drink and the first incidence of adult-onset DSM-IV alcohol use disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32(12):2149–2160. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duranceaux NC, Schuckit MA, Luczak SE, Eng MY, Carr LG, Wall TL. Ethnic differences in level of response to alcohol between Chinese Americans and Korean Americans. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(2):227–234. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder JP, Campbell NR, Litrownik AJ, Ayala GX, Slymen DJ, Parra-Medina D, Lovato CY. Predictors of cigarette and alcohol susceptibility and use among Hispanic migrant adolescents. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31(2 Pt 1):115–123. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, McCaffrey DF, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Longshore DL. New inroads in preventing adolescent drug use: Results from a large-scale trial of project ALERT in middle schools. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(11):1830–1836. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ, Saner H. Antecedents and outcomes of marijuana use initiation during adolescence. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39(5):976–984. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillmore MR, Catalano RF, Morrison DM, Wells EA, Iritani B, Hawkins JD. Racial differences in acceptability and availability of drugs and early initiation of substance use. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1990;16(3–4):185–206. doi: 10.3109/00952999009001583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Maskarinec G, Carlin L. Ethnicity, sense of coherence, and tobacco use among adolescents. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;29(3):192–199. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2903_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunbaum JA, Lowry R, Kann L, Pateman B. Prevalence of health risk behaviors among Asian American/Pacific Islander high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27(5):322–330. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Lahiff M, Guterman NB. Acculturation and parental attachment in Asian-American adolescents' alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33(2):119–129. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Wong FY, Huang ZJ, Ozonoff A, Lee J. Substance use among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders sexual minority adolescents: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42(3):275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harachi TW, Catalano RF, Kim S, Choi Y. Etiology and prevention of substance use among Asian American youth. Prevention Science. 2001;2(1):57–65. doi: 10.1023/a:1010039012978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, Collins SE, George WH, Wall TL, McCarthy DM, Liang T, Larimer ME. Associations of ALDH2 and ADH1B genotypes with alcohol-related phenotypes in Asian young adults. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33(5):839–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00903.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, Dillworth TM, Neighbors C, George WH. Differential effects of acculturation on drinking behavior in Chinese- and Korean-American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(1):121–128. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, MacPherson L, Myers MG, Carr LG, Wall TL. Psychosocial, cultural and genetic influences on alcohol use in Asian American youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(2):185–195. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipwell AE, White HR, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Chung T, Sembower MA. Young girls' expectancies about the effects of alcohol, future intentions and patterns of use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005:630–639. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffel EM, Rastogi S, Kim MO, Shahid H. The Asian population: 2010: 2010 census briefs. US Census Bureau; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Iritani BJ, Halpern CT, Bauer DJ. Sexual behavior and drug use among Asian and Latino adolescents: Association with immigrant status. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2007;9(2):85–94. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RA, Hoffmann JP. Adolescent cigarette smoking in U.S. racial/ethnic subgroups: Findings from the National Education Longitudinal Study. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2000;41(4):392–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Volume I: Secondary school students. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2008. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2007; p. 707. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2008. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Drug Abuse; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Martino SC, Ellickson PL, Longshore DL. “But others do it!”: Do misperceptions of schoolmate alcohol and marijuana use predict subsequent drug use among young adolescents? Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2001;37(4):740–758. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Kiros GE, Schaffran C, Hu MC. Racial/ethnic differences in cigarette smoking initiation and progression to daily smoking: A multilevel analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(1):128–135. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan CP, Zabkiewicz D, McPhee SJ, Nguyen T, Gregorich SE, Disogra C, Jenkins C. Health-compromising behaviors among Vietnamese adolescents: The role of education and extracurricular activities. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;32(5):374–383. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KM, Chassin L. A prospective study of the effects of age of initiation of alcohol and drug use on young adult substance dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68(2):256–265. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komro KA, McCarty MC, Forster JL, Blaine TM, Chen V. Parental, family, and home characteristics associated with cigarette smoking among adolescents. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2003;17(5):291–299. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-17.5.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: Modeling the externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(3):411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Rodrigues A, Schiffman J, Tawalbeh S. Early alcohol initiation increases risk related to drinking among college students. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2007;17(2):125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Richardson JL, Klonoff EA, Flay B. Cultural diversity in the predictors of adolescent cigarette smoking: The relative influence of peers. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;17(3):331–346. doi: 10.1007/BF01857956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le TN, Goebert D, Wallen J. Acculturation factors and substance use among Asian American youth. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30(3–4):453–473. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JP, Battle RS, Lipton R, Soller B. 'Smoking': Use of cigarettes, cigars and blunts among Southeast Asian American youth and young adults. Health Education Research. 2010;25(1):83–96. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Pentz MA, Chou CP. Parental substance use as a modifier of adolescent substance use risk. Addiction. 2002;97(12):1537–1550. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luczak SE, Wall TL, Cook TA, Shea SH, Carr LG. ALDH2 status and conduct disorder mediate the relationship between ethnicity and alcohol dependence in Chinese, Korean, and White American college students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(2):271–278. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luczak SE, Wall TL, Shea SH, Byun SM, Carr LG. Binge drinking in Chinese, Korean, and White college students: Genetic and ethnic group differences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15(4):306–309. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum C, Corliss HL, Mays VM, Cochran SD, Lui CK. Differences in the drinking behaviors of Chinese, Filipino, Korean, and Vietnamese college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(4):568–574. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Iacono WG, Krueger R. The association of early adolescent problem behavior and adult psychopathology: A multivariate behavioral genetic perspective. Behavior Genetics. 2006;36(4):591–602. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9061-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier MH, Slutske WS, Arndt S, Cadoret RJ. Positive alcohol expectancies partially mediate the relation between delinquent behavior and alcohol use: generalizability across age, sex, and race in a cohort of 85,000 Iowa schoolchildren. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(1):25–34. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MG, Doran NM, Trinidad DR, Wall TL, Klonoff EA. A prospective study of cigarette smoking initiation during college: Chinese and Korean American students. Health Psychology. 2009;28(4):448–456. doi: 10.1037/a0014466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices. Find interventions. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.nrepp.samhsa.gov.

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Substance use and ethnicity: Differential impact of peer and adult models. Journal of Psychology. 1986;120(1):83–95. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1986.9712618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oei TP, Burrow T. Alcohol expectancy and drinking refusal self-efficacy: A test of specificity theory. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25(4):499–507. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oei TP, Fergusson S, Lee NK. The differential role of alcohol expectancies and drinking refusal self-efficacy in problem and nonproblem drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59(6):704–711. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oei TP, Jardim CL. Alcohol expectancies, drinking refusal self-efficacy and drinking behaviour in Asian and Australian students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87(2–3):281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oei TP, Morawska A. A cognitive model of binge drinking: The influence of alcohol expectancies and drinking refusal self-efficacy. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(1):159–179. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds RS, Thombs DL, Tomasek JR. Relations between normative beliefs and initiation intentions toward cigarette, alcohol and marijuana. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37(1):75. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando M, Ellickson PL, McCaffrey DF, Longshore DL. Mediation analysis of a school-based drug prevention program: Effects of Project ALERT. Prevention Science. 2005;6(1):35–46. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-1251-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuki TA. Substance use, self-esteem, and depression among Asian American adolescents. Journal of Drug Education. 2003;33(4):369–390. doi: 10.2190/RG9R-V4NB-6NNK-37PF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padula CB, Schweinsburg AD, Tapert SF. Spatial working memory performance and fMRI activation interaction in abstinent adolescent marijuana users. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:478–487. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RK, Risk NK, Wong MM, Klingle RS. Substance use and abuse by Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: Preliminary results from four national epidemiologic studies. Public Health Reports. 2002;117(Suppl 1):S39–S50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves TJ, Bennett CE. We the people: Asians in the United States. 2004 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2004pubs/censr-17.pdf.

- Rinehart CS, Bridges LJ, Sigelman CK. Differences between Black and White elementary school children's orientations toward alcohol and cocaine: A three-study comparison. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2006;5(3):75–102. doi: 10.1300/J233v05n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodham K, Hawton K, Evans E, Weatherall R. Ethnic and gender differences in drinking, smoking and drug taking among adolescents in England: A self-report schoolbased survey of 15 and 16 year olds. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28(1):63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasao T. Identifying at-risk Asian American adolescents in multiethnic schools: Implications for substance abuse prevention interventions and program evaluation. 1999:143–167. DHHS Publication No. SMA 98–3193. [Google Scholar]

- Schweinsburg AD, Brown SA, Tapert SF. The influence of marijuana use on neurocognitive functioning in adolescents. Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 2008;1(1):99–111. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801010099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih RA, Miles JNV, Tucker JS, Zhou AJ, D'Amico EJ. Racial/ethnic differences in adolescent substance use: Mediation by individual, family, and school factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:640–651. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. Adolescent period: Biological basis of vulnerability to develop alcoholism and other ethanol mediated behaviors. In: Noronha A, Eckardt M, Warren K, editors. Review of NIAAA's Neuroscience and Behavior Research Portfolio. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Spruijt-Metz D, Gallaher P, Unger JB, Johnson CA. Unique contributions of meanings of smoking and outcome expectancies to understanding smoking initiation in middle school. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;30(2):104–111. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Table 2.38B - Alcohol Use in Lifetime, Past Year, and Past Month among Persons Aged 12 to 17, by Demographic Characteristics: Percentages 2010 and 2011. 2011a Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2011SummNatFindDetTables/NSDUH-DetTabsPDFWHTML2011/2k11DetailedTabs/Web/HTML/NSDUH-DetTabsSect2peTabs1to42-2011.htm#Tab2.38B.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Table 2.23B – Cigarette Use in Lifetime, Past Year, and Past Month among Persons Aged 12 to 17, by Demographic Characteristics: Percentages, 2010 and 2011. 2011b Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2011SummNatFindDetTables/NSDUH-DetTabsPDFWHTML2011/2k11DetailedTabs/Web/HTML/NSDUH-DetTabsSect2peTabs1to42-2011.htm#Tab2.23B.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Table 1.25B – Marijuana Use in Lifetime, Past Year, and Past Month among Persons Aged 12 to 17, by Demographic Characteristics: Percentages, 2010 and 2011. 2011c Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2011SummNatFindDetTables/NSDUH-DetTabsPDFWHTML2011/2k11DetailedTabs/Web/HTML/NSDUH-DetTabsSect1peTabs1to46-2011.htm#Tab1.25B.

- Taylor P. The rise of Asian Americans. Pew Research Social & Demographic Trends, 1–225. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2012/06/SDT-The-Rise-of-Asian-Americans-Full-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Thai ND, Connell CM, Tebes JK. Substance use among Asian American adolescents: Influence of race, ethnicity, and acculturation in the context of key risk and protective factors. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2010;1(4):261–274. doi: 10.1037/a0021703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towberman DB, McDonald RM. Dimensions of adolescent drug-avoidant attitude. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1993;10(1):45–52. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90097-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Chen X. The role of social networks and media receptivity in predicting age of smoking initiation: a proportional hazards model of risk and protective factors. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24(3):371–381. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Rohrbach LA, Cruz TB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Howard KA, Palmer PH, Johnson CA. Ethnic variation in peer influences on adolescent smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2001;3(2):167–176. doi: 10.1080/14622200110043086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US DHHS. NIH policy and guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research. 2001 Retrieved from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/women_min/guidelines_amended_10_2001.htm.

- van der Vorst H, Engels RC, Meeus W, Dekovic M, Van Leeuwe J. The role of alcohol-specific socialization in adolescents' drinking behaviour. Addiction. 2005;100(10):1464–1476. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall TL, Shea SH, Chan KK, Carr LG. A genetic association with the development of alcohol and other substance use behavior in Asian Americans. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110(1):173–178. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Jr, Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE, Cooper SM. Tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use: Racial and ethnic differences among U.S. high school seniors, 1976– 2000. Public Health Reports. 2002;117(Suppl 1):S67–S75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Jr, Vaughn MG, Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic factors, and smoking among early adolescent girls in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;104(Suppl 1):S42–S49. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner LA, White HR. Longitudinal effects of age at onset and first drinking situations on problem drinking. Substance Use & Misuse. 2003;38(14):1983–2016. doi: 10.1081/ja-120025123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WestEd. California Healthy Kids Survey. 2008 Retrieved from www.wested.org/hks. [Google Scholar]

- Wiecha JM. Differences in patterns of tobacco use in Vietnamese, African-American, Hispanic, and Caucasian adolescents in Worcester, Massachusetts. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1996;12(1):29–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. Parental, sibling, and peer influences on adolescent substance use and alcohol problems. Applied Development Science. 2000;4:96–110. [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Behrendt S, Hofler M, Perkonigg A, Lieb R, Buhringer G, Beesdo K. What are the high risk periods for incident substance use and transitions to abuse and dependence? Implications for early intervention and prevention. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2008;17(Suppl 1):S16–S29. doi: 10.1002/mpr.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Klingle RS, Price RK. Alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use among Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents in California and Hawaii. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(1):127–141. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]