Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Consensus on normal translabial ultrasound (TL-US) anal sphincter complex measurements for postpartum women is lacking. We aimed to evaluate normative measurements in 2D and 3D TL-US for the anal sphincter complex (ASC) at 6 months postpartum and compare these measurements in women who had a vaginal birth (VB) and in those who had a Cesarean delivery (CD).

Methods

A large, prospective cohort of primiparous women underwent 2D and 3D TL-US 6 months after their first delivery. For normative sphincter measurements, we excluded women with third- or fourth-degree lacerations or with sphincter interruption on TL-US. Measurements included the sphincter thickness at the 3, 6, 9, and 12 o'clock positions of the external anal sphincter (EAS) and the internal anal sphincter (IAS) at proximal, mid, and distal levels. We also measured the mean coronal diameter of the pubovisceralis muscle (PVM).

Results

696 women consented to participate, and 433 women presented for ultrasound imaging 6 months later. Women who sustained a third- or fourth-degree laceration had significantly thicker EAS measurements at 12 o'clock. Sphincter asymmetry was common (69 %), but was not related to mode of delivery. Only IAS measurements at the proximal and distal 12 o'clock position were significantly thicker for CD patients. There were no significant differences in the EAS or PVM measurements between VB and CD women.

Conclusions

There appear to be few differences in normative sphincter ultrasound measurements between primiparous patients who had VB or CD.

Keywords: Anal sphincter, Muscle, Measurements, Postpartum, Ultrasound

Introduction

Damage to the anal sphincter complex (ASC) during childbirth can result in long-lasting bowel control problems following delivery [1,2]. Three fourths of the cases of fecal incontinence (FI) follow some type of sphincter injury [3]. Gaps in knowledge about how muscle integrity corresponds to normal changes after a birth may contribute to the disappointing results seen in attempts at surgical correction of sphincter defects [4]. Estimates of sphincter injury rates vary widely and occur more commonly in women who undergo forceps deliveries [5–7]. Damage to the anal sphincter complex has been associated with fecal incontinence symptoms, with different locations and extent of muscle injury having different effects on symptomatology [7–10].

Ultrasound imaging is considered a reliable, cost-effective, and widely available method of evaluating ASC integrity [11–13], and ASC ultrasound imaging is vital to the diagnosis and treatment of anal disorders [14]. Unfortunately, normal values for thickness of the anal sphincter musculature are not well established. A standard method of evaluating ASC damage and objective measurements that constitute a “normal” ASC thickness would aid in the description and diagnosis of ASC damage following birth. Past studies have generated nomograms from small cohorts of patients [7, 15–17], but the heterogeneity of patient populations and inconsistent imaging modalities (translabial, transperineal, and endoanal) in these studies are notable barriers to establishing normal findings postpartum [18].

Normative sphincter measurements may differ based on the mode of delivery. A common hypothesis is that Cesarean delivery would better preserve pelvic musculature, resulting in thicker measurements of the ASC and levator ani during postpartum ultrasound evaluation. While it has been shown that pelvic organ dysfunction is associated with levator damage and birth trauma, it has not yet been consistently found that women delivering by Cesarean section have different postpartum anal sphincter anatomy from women delivering vaginally [19, 20]. It is not known what specific ultrasound findings can be expected in a large population of women who have undergone vaginal birth (VB) as opposed to a Cesarean delivery (CD).

The aim of this study was to establish normal measurements of the ASC and PVM using TL-US in primiparous women 6 months postpartum and compare these measurements between women who had differing modes of delivery. We consider normative measurements of the anal sphincter to be measurements in women who have not sustained a third or fourth degree interruption and are not found to have interrupted sphincters on imaging. We hypothesized that normative values for muscle thickness could be established in this large population undergoing 2D and 3D TL-US imaging, and that these measurements would be thinner in some locations for women who had a VB versus women who had undergone a CD.

Materials and methods

This study is a planned secondary assessment of data collected as part of a parent study designed to evaluate postpartum pelvic floor changes following delivery of a first child. Nulliparous, healthy women who presented to prenatal care with the University of New Mexico midwives were recruited prenatally and an additional cohort who delivered their first child by CD without entering the second stage of labor were recruited immediately postpartum. This study was approved by the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center Internal Review Board (IRB). Informed written consent was given by all participants.

Labor and maternal characteristics were gathered at the birth and included a detailed examination of all lacerations to the genital tract sustained during delivery. Women with a second degree perineal laceration or higher were evaluated by a second examiner to ensure that the lacerations were graded appropriately. All third and fourth degree lacerations were repaired at the time of delivery, with standard repair methodology including identification and repair of the IAS with polygalactin sutures and repair of the EAS in an end-to-end or overlapping fashion with PDS suture.

All study participants were scheduled to undergo 6-month postpartum 2D and 3D TL-US imaging of the ASC. Women who presented for 6-month postpartum ultrasound were also encouraged to undergo endoanal ultrasound during that examination, although this paper will be focused solely on the translabial ultrasound findings. Examinations were performed in the lithotomy position. All examinations were performed by one of the principal investigators (RH) or by fellows in the field of pelvic medicine who were directly supervised by this investigator. All sonographers were blinded to the patients' delivery history.

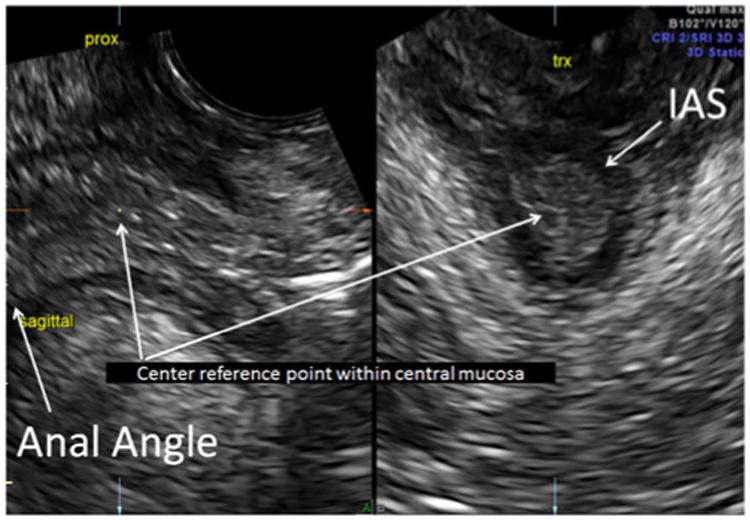

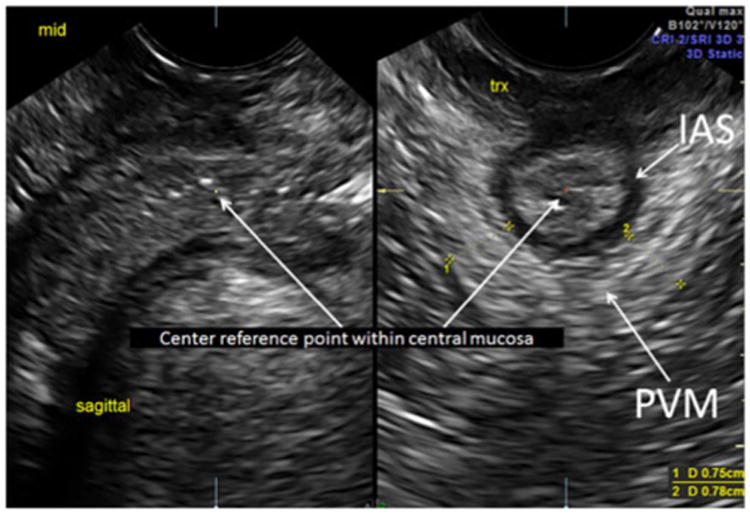

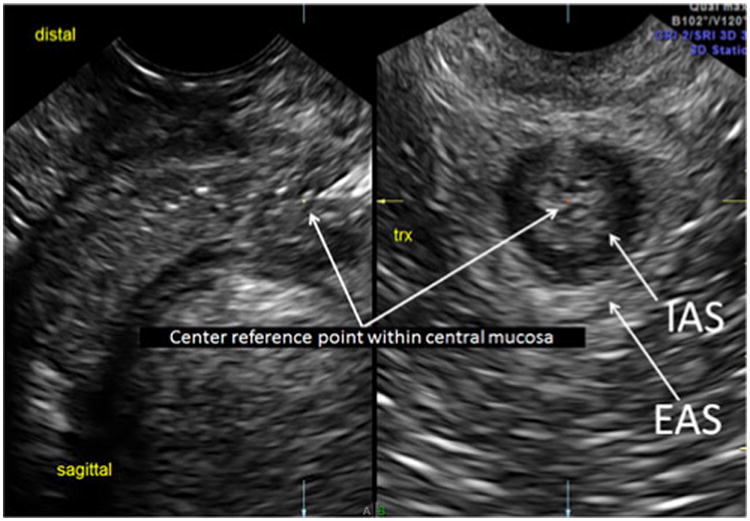

Our methodology has been previously described and found to have high inter-rater reliability; thus, this protocol was used for imaging the ASC in this study [17]. We acquired all 2D and 3D measurements and 3D volume sets using the GE E8 ultrasound system with the 5- to 9-MHz endovaginal transducer (Milwaukee, WI, USA) or the Phillips IU22 with the 4-to 8-MHz endovaginal transducer (Bothell, WA, USA). The endovaginal transducer was placed at the introitus in a transverse plane, angling nearly perpendicular to the floor. With transducer angle manipulation from superior to inferior, the ASC was seen at multiple planes, the proximal, mid, and distal levels of the ASC (Figs. 1, 2 and 3). This has been described in previous studies regarding levels of the rectum [21]. The proximal level was the IAS just distal to the anal angle, the mid level was the location at which the pubovisceralis muscle (PVM) could be seen passing posteriorly to the IAS, and the distal level was the level at which the IAS and EAS were optimally imaged together. Each 2D and 3D volume set was stored in the PACS system of our imaging center.

Fig. 1. Proximal anal sphincter complex (ASC): center reference point of the 3D sagittal acquisition plane demonstrates proximal internal anal sphincter (IAS) location just distal to the anal angle and at a transverse cut.

Fig. 2. Mid ASC: center reference point of the 3D sagittal acquisition plane demonstrates mid-level ASC in the sagittal view and at a transverse cut. Note that this view demonstrates the mid IAS and the measurements of the pubovisceralis muscle (PVM).

Fig. 3. Distal ASC: center reference point of the sagittal acquisition A plane is moved distally to optimize the EAS (arrows) and IAS (arrows) in the same view on the transverse B plane, which represents the distal level of the ASC.

We made a full survey of the IAS and EAS complex, which included visualization of the PVM, in 3D imaging in order to select the best plane and location in which to make measurements of muscle thickness. Measurements in a transverse plane included 1) 2D Anterior Posterior (AP) diameters of the 12, 3, 6, and 9 o'clock positions of the IAS at proximal, mid and distal levels, 2) 2D AP diameters of the 12, 3, 6, and 9 o'clock EAS, and 3) 2D and 3D pubovisceralis muscle AP diameter. The transducer was then turned 90° from the axial plane to a mid-sagittal plane to acquire 3D volume sets. Volume sweeps were made with a 75° sweep angle and high quality resolution (slow sweep). Comparative 3D translabial measurements of the IAS/EAS complex at 12, 3, 6, and 9 o'clock at proximal, mid and distal levels were obtained from the volume set, as was the widest bilateral AP diameter of the transverse pubovisceral muscle (PVM). This widest bilateral AP diameter of the PVM was consistently at 4 and 8 o'clock at the mid IAS level as described by previous authors [15, 22]. 2D TL-US and 3D TL-US measurements with squeeze and with Valsalva were also obtained.

We describe 3D planes as being related to the specific anatomy being measured versus the body, because the position of each of the pelvic floor structures was not aligned with 3D rotated planes. Though some ultrasound imaging and MRI authors describe ultrasound cuts to the body plane [7], we describe planes (i.e., the axial plane) relative to the organ being measured (i.e. the rectum) rather than relative to the body, thus accounting for the variation in locations of all anatomical structures. This is consistent with standard practice in diagnostic ultrasound imaging, and is described in this manner by other authors measuring the anal sphincter complex [15].

No measurements were obtained when compromised resolution demanded that specialty imaging techniques, such as slice thickness (volume contrast imaging), be used. We acquired all our 3D volume sets in the midline sagittal plane (A Plane). Our 3D ASC measurements were taken at the plane transverse to the midline sagittal plane (B Plane) and we utilized these planes and the coronal plane (C Plane) to manipulate the images and correctly align the overall volume. To properly maximize the pubovisceralis thickness and measure the perimeters of the inner and outer planes, the volume set was manipulated by X, Y, and Z axis rotations. We chose to produce a subset of short field of view (FOV) 2D and manipulated 3D in order to optimize the thickest transverse PVM cut. Our described PVM images are most optimally measured at the pivotal 4 and 8 o'clock locations, which is seen best at the mid IAS level on 2D and the B Plane on 3D. This study did not include the coronal view of the hiatus, where much of the described avulsion pathology has been noted, as we purposely decreased our FOV to increase resolution.

We defined muscle interruption as a complete discontinuity in the muscle at a given location. The definition of sphincter asymmetry was a measurement in one muscle quadrant (3, 6, 9, or 12 o'clock) that was <50 % of the mean of the measurements for the other three quadrants for that muscle at that level. An intact PVM was defined as a continuous and symmetrical pubovisceralis muscle sling immediately surrounding the rectum, not the anterior attachment of this muscle. Women with third- or fourth-degree lacerations at the time of delivery or complete IAS or EAS interruption on 6-month postpartum TL-US were excluded from analysis of normative measurements for the anal sphincters.

As this was a secondary analysis of a larger study evaluating postpartum pelvic floor changes, the study was initially powered for a parent study that is still in progress. Normative ultrasound measurement values are reported as means ± standard deviations separately for each mode of delivery. Continuous variables were compared using t tests. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-squared analysis or Fisher's exact test. All statistical analysis was performed using SAS programming.

Results

Between July 2006 and December 2011, 782 women consented prenatally and post-Cesarean delivery to participate, 696 of whom delivered at the University of New Mexico: 448 delivering by VB, 246 delivering by CD, and 2 women deemed ineligible after recruitment owing to the discovery that they had had preterm vaginal births at <37 weeks' gestation. There was 1 forceps delivery, 25 vacuum deliveries (6 % of VB), and 8 episiotomies (2 % of VB) in this study. Of women who had CD, the majority were recruited postoperatively and never entered the second stage of labor. Of women who had a CD, 93 were patients of the midwifery practice who entered the first stage of labor and proceeded to have a CD, and 155 were patients who had a CD and were recruited postpartum. Only 24 midwifery patients entered the second stage and pushed prior to having a CD; these 24 women were analyzed in the CD group and none of them sustained a third- or fourth-degree laceration or had interruption of the sphincters on their 6-month postpartum ultrasound imaging. Thus, 90 % of the CD group never entered the second stage of labor.

Of women eligible to undergo an ultrasound examination at 6 months postpartum, 433 out of 694 (62 %) presented for ultrasound imaging (299 VB and 134 CD). Women who presented for ultrasound had more years of education (13.99±2.74 vs 13.53±2.86 years, p =0.04) and were more likely to have undergone a VB than women who did not present for 6-month postpartum ultrasound (69 % vs 56 % VB, p <0.01), but were otherwise similar in baseline characteristics. Women who had a CD were significantly older, had a significantly higher pre-pregnancy BMI, and were more likely to have had an epidural or received oxytocin than women who had VB (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient and labor characteristics of women who had vaginal birth (VB) versus Cesarean delivery (CD).

| VB n = 299 | CD n = 134 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 24.43±5.07 | 26.72±6.20 | <0.01 |

| Education (years) (mean ± SD) | 14.06±2.76 | 13.84±2.71 | 0.47 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD) | 24.75±5.40 | 26.65±25.60 | <0.01 |

| Weight gain in pregnancy (kg; mean ± SD) | 16.19±6.40 | 15.90±7.81 | 0.71 |

| Fetal birth weight (g; mean ± SD) | 3206.5±432.7 | 3262.8±512.3 | 0.27 |

| Race (%) | 0.71 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 133 (44) | 54 (41) | |

| Hispanic | 127 (42) | 59 (44) | |

| Other | 39 (13) | 20 (15) | |

| Tobacco use (%) | 17 (5.7) | 11 (8.5) | 0.29 |

| Vacuum delivery(%) | 15 (5) | 0 | N/A |

| Epidural (%) | 176 (59) | 85 (63) | 0.4 |

| Oxytocin (%) | 139 (47) | 81 (60) | 0.01 |

| Episiotomy (%) | 6 (2) | 0 | 1.0 |

| Perineal length before delivery (cm; mean ± SD) | 4.17±4.06 | 4.13±3.85 | 0.8 |

| Active second stage (min; mean ± SD) | 74.14±65.41 | N/A | N/A |

| Perineal laceration (%) | 166 (56) | 0 | N/A |

| 1st degree | 60 (20) | ||

| 2nd degree | 87 (29) | ||

| 3rd degree | 16 (5) | ||

| 4th degree | 3 (1) |

Second observers were present for 91 out of 151 (60 %) of second degree or greater lacerations (n =129 second degree, n =19 third degree, and n =3 fourth degree lacerations) at the time of delivery, with 98 % agreement between observers. The rate of third and fourth degree lacerations in women with a VB in the study population was 4.9 % (22 out of 448). The rate of third- and fourth-degree lacerations in the population of women with VB who later presented for 6-month postpartum ultrasound was 6.5 % (19 out of 291; 16 third degree and 3 fourth degree lacerations), There was a low rate of sphincter interruptions on ultrasound imaging at 6 months postpartum (4 EAS separations and 36 IAS separations in 38 women, 33 VB and 5 CD). Most women with a sphincter interruption on 6-month postpartum ultrasound (n =38) had disruption of the IAS at the 12 o'clock position (31 out of 38 [82 %]), with the 12 o'clock distal IAS being the most common interruption site (19 out of 38 [50 %]).

There were no significant differences in the rates of an intact IAS or intact EAS between CD and VB women at any location on TL-US. In nearly all women (99 %) the distal IAS and EAS were visualized. The rate of intact distal IAS was similar in CD and VB women (96 % vs 94 %, p=0.33), and 99 % of both CD women and VB women had an intact EAS at 12 o'clock. None of the women had a disrupted sphincter on any other quadrants of the EAS (3, 6, or 9 o'clock).

Women who sustained a third- or fourth-degree laceration were not more likely to have an ultrasound-recognized disruption at the proximal IAS (0 out of 19 [0 %] vs 14 out of 404 (3 %), p =0.41), mid IAS (1 out of 18 [6 %] vs 9 out of 404 [2 %], p =0.36), or the distal IAS (1 out of 19 [5 %] vs 22 out of 402 [5 %], p =0.97) compared with those women without a history of severe laceration, although numbers were small in these categories. Women who sustained a third or fourth degree laceration were also no more likely to have an EAS separation at 12 o'clock than women without this laceration history (0 out of 19 vs 4 out of 402 [1 %], p =1.0). A repaired third or fourth degree laceration diagnosed at the time of delivery did not significantly change any IAS measurements. However, women with a history of a repaired third or fourth degree laceration did have a slightly thicker EAS muscle measurement at 12 o'clock compared with women who had no history of third or fourth degree laceration (2.57±0.83 vs 2.11±0.83 mm, p =0.03).

Four hundred and twenty-three women (291 VB and 132 CD) had sphincter measurement data on 6-month postpartum ultrasound, and 368 of these patients (87 %; 242 VB and 126 CD) were eligible for normative measurement analysis of the anal sphincters. Women who sustained third- or fourth-degree lacerations (n =19) or had interrupted sphincters on 6-month postpartum ultrasound imaging (n =36 additional women) were excluded from the normative value analysis of the anal sphincters. As mentioned above, there were two women who sustained third degree lacerations and showed interruption of sphincters on the 6-month postpartum imaging. For the IAS, measurements did not differ significantly between women who had VB and women who had CD, with the exception of the 12 o'clock position at the proximal and distal IAS (Table 2). There were no significant differences in normative values of EAS measurements between CD and VB women.

Table 2. Translabial 2-D ultrasound normative values of anal sphincter thickness: vaginal birth (VB) versus Cesarean delivery (CD).

| Normal vaginal birth (mean ± SD in mm) n=242 | Cesarean section (mean ± SD in mm) n = 126 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean proximal IAS thickness | |||

| At 12 o'clock | 1.99±0.83 | 2.25±0.85 | <0.01 |

| At 3 o'clock | 2.17±0.62 | 2.22±0.69 | 0.52 |

| At 6 o'clock | 1.94±0.67 | 2.02±0.80 | 0.33 |

| At 9 o'clock | 2.20±0.64 | 2.29±0.71 | 0.25 |

| Mean mid IAS thickness | |||

| At 12 o'clock | 2.08±0.70 | 2.24±0.74 | 0.06 |

| At 3 o'clock | 2.28±0.61 | 2.26±0.64 | 0.74 |

| At 6 o'clock | 1.90±0.63 | 1.95±0.70 | 0.51 |

| At 9 o'clock | 2.36±0.62 | 2.36±0.62 | 0.99 |

| Mean distal IAS thickness | |||

| At 12 o'clock | 2.10±0.63 | 2.24±0.67 | 0.04 |

| At 3 o'clock | 2.22±0.55 | 2.28±0.60 | 0.38 |

| At 6 o'clock | 2.24±0.72 | 2.17±0.60 | 0.34 |

| At 9 o'clock | 2.35±0.60 | 2.37±0.60 | 0.8 |

| Mean distal EAS thickness | |||

| At 12 o'clock | 2.11±0.85 | 2.03 ±0.75 | 0.36 |

| At 3 o'clock | 3.66±1.63 | 3.57±1.68 | 0.63 |

| At 6 o'clock | 4.09±2.15 | 3.98±2.19 | 0.62 |

| At 9 o'clock | 3.80±1.74 | 3.65±1.55 | 0.42 |

Normative values of PVM measurements were established for the 426 women who had 2D or 3D TL-US measurements of this muscle (294 VB and 119 CD); there were no significant differences between women who had CD and VB (Table 3). All women with a CD delivery and 97 % of women who had VB had PVM visualized and intact bilaterally; there were no significant differences in the rate of an intact PVM at rest or with pelvic maneuvers between CD and VB women.

Table 3. Pubovisceralis muscle (PVM) measurements: vaginal birth (VB) versus Cesarean delivery (CD).

| Normal Vaginal birth (mean ± SD in mm) n=294 | Cesarean Section (mean ± SD in mm) n =119 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean coronal transverse diameter (3-D) | |||

| At rest | |||

| Right | 7.01 ±1.77 | 6.98±1.73 | 0.85 |

| Left | 7.30±1.85 | 7.15±1.90 | 0.47 |

| With pelvic floor squeeze | |||

| Right | 7.40±3.72 | 7.29±1.80 | 0.66 |

| Left | 7.76±3.58 | 7.49±1.94 | 0.31 |

| With Valsalva | |||

| Right | 7.90±8.16 | 7.97±8.21 | 0.94 |

| Left | 8.22±8.12 | 8.13±8.21 | 0.91 |

| Mean coronal transverse diameter (at rest) | |||

| Translabial 2-D | |||

| Right | 6.90±1.63 | 7.14±1.55 | 0.18 |

| Left | 7.21 ±1.66 | 7.30±1.70 | 0.61 |

Since the occurrence of sphincter separations was low, we explored the rates of asymmetry of the ASC sphincter muscles in the VB and CD groups. As noted above, we defined asymmetry of a muscle as measurement of one quadrant of muscle <50 % of the mean of other quadrants. Asymmetry in some level of some muscle was observed in 292 women, 233 of whom had asymmetry of the EAS. Neither rate of asymmetry at the EAS (134 out of 241 [56 %]) asymmetry for VB vs 72 out of 126 (57 %) for CD, p =0.82) nor asymmetry in any sphincter at any level (200 out of 291 [69 %] asymmetry for VB vs 92 of the 132 [70 %] for CD, p =0.99) was associated with mode of delivery. A history of third or fourth degree laceration was not associated with asymmetry in any location (11 out of 19 [58 %] asymmetry with third or fourth degree laceration vs 281 out of 404 (70 %) without third or fourth degree laceration, p = 0.31). Of note, sphincters found to have asymmetry had significantly thicker mean measurements of the EAS at 12 o'clock compared with sphincters that were not asymmetric (2.19±0.99 vs 2.0± 0.64 mm, p =0.03).

Discussion

We found that there are few differences in normative sphincter measurements between VB and CD for primiparous women exposed to low levels of episiotomy and operative vaginal birth. Measurement of IAS muscle thickness ranged from 1.90 to 2.37 mm, and for the EAS from 2.03 mm to 4.09 mm, and most measurements were similar between VB and CD. The exception was the IAS at the 12 o'clock location, which is significantly thinner proximally and distally in women who have had a VB. The clinical utility of these measurements is that, with the exception of very small differences in these two isolated locations, the average sphincter measurements of normal women without sphincter interruption should be considered similar regardless of mode of delivery.

We found that the majority of women have some asymmetry of their anal sphincter complex, as measured by 2D TL-US. We explored asymmetry as a possible surrogate for partial damage in the anal sphincter muscles, but its lack of association with delivery mode supports that asymmetry is not a marker for partial disruptions. This study joins other research indicating that sphincter thinning or asymmetry, particularly at the 12 o'clock position, is not merely a product of birth injury or mode of delivery [23, 24]. An ultrasound study of 55 nulliparous women described thinner EAS measurements at the 12 o'clock position, indicating that this asymmetric anatomy is present even when no pregnancy or delivery has occurred [23]. The clinical significance of a thinner muscle is also unclear, as some studies show that the sphincter measurements may not relate to incontinence and that the anterior EAS may be naturally shorter than the remainder of the muscle in the absence of any injury [24]. Studies investigating sphincter anatomy in women should take into account the frequency with which notable asymmetry is seen, and not establish the normalcy of sphincter anatomy based on only one quadrant.

The field has not clearly established normative measurements of thickness for the anal sphincter musculature, particularly for women with differing modes of delivery. Prior series have been smaller, included a wide range of age and parity for women, and in some instances included men [16, 24–26]. Research demonstrates that women naturally have shorter sphincters than men [15] and their sphincter thickness changes with age [26]. The role of parity in sphincter thickness and anal symptoms is also unclear [4, 24, 25]. Despite these issues, we compared our data with past ultrasound measurements of the ASC. Nearly two decades ago, examiners used a “pseudo-3D” method of measuring the ASC at multiple levels to determine a mean EAS thickness of 3.5 mm and a mean IAS thickness of 2.3 mm [16]. A more recent transperineal ultrasound study of 139 postpartum, primiparous women established mean IAS measurements of 2.6 mm, 2.55 mm, 2.6 mm, and 2.72 mm at 12, 3, 6, and 9 o'clock respectively, and EAS measurements were nearly twice that thickness at 4.15 mm, 4.2 mm, 4.21 mm, and 4.20 mm at 12, 3, 6, and 9 o'clock respectively [27]. A smaller study using transperineal ultrasound measured the IAS at 2.3–2.9 mm and the PVM at 6.4–6.5 mm [22].

The findings in the present study were similar to these past measurements of the IAS. However, our EAS thickness measurements (2.03–4.09 mm) were somewhat smaller than in these previous reports, especially at the 12 o'clock position, and our PVM measurements were somewhat larger (6.90–8.22 mm). This may be due to our protocol of translabial imaging, although this methodology had been found to have high inter-rater reliability in a prior study [17]. These differences may also be due to the particular characteristics of the low-risk population in this study. Interestingly, our EAS thickness values were quite similar to prior reports with MRI [28, 29].

The present study did not find any significant difference in PVM thickness between women who have had a CD and those who have undergone VB. Imaging studies demonstrate that levator avulsion is more common in women who have VB and nearly absent in women who undergo CD [30], but few studies explore if there is PVM thinning resulting from birth injury. There is evidence that pelvic floor dysfunction is associated with parity regardless of mode of delivery. However, a past TL-US study shows that pelvic organ descent is progressively worse from CD to VB to operative vaginal birth [31]. A plethora of research upholds that levator avulsion, an injury connected to vaginal parity, is highly correlated with pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic organ descent [8, 28]. We did not specifically set out to investigate levator avulsion and measured only PVM thickness; thus, we may not have captured all clinically relevant levator damage.

We detected almost no measurement differences between women who had sphincter laceration at delivery and those who did not. The notable exception was an increase in sphincter thickness at the 12 o'clock EAS in women who sustained and had repair of a third- or fourth-degree laceration. This unexpected finding may be due to post-repair scar formation or subsequent healing, and could represent a population that had adequate EAS laceration repair. This population was at low risk of severe lacerations partly because the very low rate of episiotomy and operative delivery in this study. The rarity of these lacerations also makes it difficult to establish their effect in a population of this size. These data revealed 5 women with the interesting finding of a sphincter interruption on ultrasound 6 months after a Cesarean delivery. Non-continuity of the sphincter in these women may be an anatomical defect that occurred before their delivery or because of non-obstetrical trauma. This could also be an error of the imaging methodology, although image datasets were re-reviewed by the authors and disruptions were still noted.

A strength of the present study is the exclusion of any sphincter interruption, either by severe laceration or any interruption of the muscle on postpartum ultrasound, from the establishment of normative sphincter measurements. This study is also one of the first to investigate the normative measurements of the ASC compared in VB and CD women. Furthermore, we distinctly defined the level and orientation of ultrasound measurements, something that is often not delineated beyond the EAS in other studies [18, 23–27].

The protocol of the parent study did not allow for us to perform antepartum ultrasound measurements in this population for comparison with the postpartum measurements; thus, we acknowledge this as a limitation to this data set. Also, the generalizability of this study is limited by its single-institution design and the restriction to only primiparous women. The VB population in this study was also delivered mostly by midwives with low rates of operative vaginal birth and episiotomy, thus, it may not be generalizable to all obstetrical populations. Also, the tendency for more educated women or women with VB to present for postpartum ultrasound may have biased our results. Despite these limitations, nearly all of the women who presented for postpartum ultrasound imaging had their sphincters both visualized and measured, furthering the hypothesis that TL-US modalities can be used effectively for postpartum evaluation of the pelvic floor musculature.

This study establishes normal expected values for ASC measurements on TL-US imaging for primiparous women who have undergone either CD or VB. There are few measurement differences between the modes of delivery, with the exception of the IAS measurements proximally and distally at 12 o'clock. This study indicates that normative values in primiparous women can be considered similar regardless of mode of delivery. This study also establishes that muscle asymmetry is common and should be considered in future research investigating sphincter anatomy. The establishment of normative values can aid our field in determining the clinical significance of measurements that fall outside normal ranges.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NICHD 1R01HD049819-01A2 and by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health through Grant Number 8UL1TR000041.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: RG Rogers: Chair DSMB for the Transform trial sponsored by American Medical Systems. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Kate V. Meriwether, Email: meriwet2@salud.unm.edu, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, NM, USA.

Rebecca J. Hall, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, NM, USA

Lawrence M. Leeman, Department of Family Medicine, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, NM, USA

Laura Migliaccio, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, NM, USA.

Clifford Qualls, Clinical Translational Sciences Center, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, NM, USA.

Rebecca G. Rogers, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, NM, USA

References

- 1.DeLancey JO. The hidden epidemic of pelvic floor dysfunction: achievable goals for improved prevention and treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1488–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel DA, Xu X, Thomason AD, Ransom SB, Ivy JS, DeLancey JO. Childbirth and pelvic floor dysfunction: an epidemiologic approach to the assessment of prevention opportunities at delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(1):23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oberwalder M, Connor J, Wexner SD. Meta-analysis to determine the incidence of obstetric anal sphincter damage. Br J Surg. 2003;90(11):1333–1337. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Bartram CI. Third degree obstetric anal sphincter tears: risk factors and outcome of primary repair. BMJ. 1994;308(6933):887–991. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6933.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Thomas JM, Bartram CI. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal birth. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(26):1905–1911. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312233292601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varma A, Gunn J, Gardiner A, Lindow SW, Duthie GS. Obstetric anal sphincter injury: prospective evaluation of incidence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(12):1537–1543. doi: 10.1007/BF02236202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinstein MM, Pretorius DH, Jung SA, Nager CW, Mittal RK. Transperineal three-dimensional ultrasound imaging for detection of anatomic defects in the anal sphincter complex muscles. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(2):205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLancey JO, Morgan DM, Fenner DE, Kearney R, Guire K, Miller JM, Hussain H, Umek W, Hsu Y, Ashton-Miller JA. Comparison of levator ani muscle defects and function in women with and without pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 Pt 1):295–302. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000250901.57095.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roos AM, Thakar R, Sultan AH. Outcome of primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS): does the grade of tear matter? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(3):368–374. doi: 10.1002/uog.7512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richter HE, Fielding JR, Bradley CS, Handa VL, Fine P, FitzGerald MP, Visco A, Wald A, Hakim C, Wei JT, Weber AM. Pelvic floor disorders network. Endoanal ultrasound findings and fecal incontinence symptoms in women with and without recognized anal sphincter tears. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(6):1394–1401. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000246799.53458.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wieczorek AP, Stankiewicz A, Santoro GA, Woźniak MM, Bogusiewicz M, Rechberger T. Pelvic floor disorders: role of new ultrasonographic techniques. World J Urol. 2011;29(5):615–623. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0708-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unger CA, Weinstein MM, Pretorius DH. Pelvic floor imaging. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2011;38(1):23–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2011.02.002. vii. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dietz HP. Pelvic floor ultrasound: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):321–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tubaro A, Koelbl H, Laterza R, Khullar V, de Nunzio C. Ultrasound imaging of the pelvic floor: where are we going? Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(5):729–734. doi: 10.1002/nau.21136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valsky DV, Yagel S. Three-dimensional transperineal ultrasonography of the pelvic floor: improving visualization for new clinical applications and better functional assessment. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26(10):1373–1387. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.10.1373. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexander AA, Miller LS, Liu JB, Feld RI, Goldberg BB. High-resolution endoluminal sonography of the anal sphincter complex. J Ultrasound Med. 1994;13(4):281–284. doi: 10.7863/jum.1994.13.4.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall RJ, Rogers RG, Saiz L, Qualls C. Translabial ultrasound assessment of the anal sphincter complex: normal measurements of the internal and external anal sphincters at the proximal, mid-, and distal levels. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(8):881–888. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0254-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roos AM, Abdool Z, Sultan AH, Thakar R. The diagnostic accuracy of endovaginal and transperineal ultrasound for detecting anal sphincter defects: the PREDICT study. Clin Radiol. 2011;66(7):597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanzarone V, Dietz HP. Three-dimensional ultrasound imaging of the levator hiatus in late pregnancy and associations with delivery outcomes. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47(3):176–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dietz HP, Shek C. Levator avulsion and grading of pelvic floor muscle strength. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(5):633–636. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delancey JO, Toglia MR, Perucchini D. Internal and external anal sphincter anatomy as it relates to midline obstetrical lacerations. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(6):924–927. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00472-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JH, Pretorius DH, Weinstein M, Guaderrama NM, Nager CW, Mittal RK. Transperineal three-dimensional ultrasound in evaluating anal sphincter muscles. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(2):201–209. doi: 10.1002/uog.4057. USA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang WC, Yang SH, Yang JM. Three-dimensional transperineal sonographic characteristics of the anal sphincter complex in nulliparous women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(2):210–220. doi: 10.1002/uog.4083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West RL, Felt-Bersma RJ, Hansen BE, Schouten WR, Kuipers EJ. Volume measurements of the anal sphincter complex in healthy controls and fecal-incontinent patients with a three-dimensional reconstruction of endoanal ultrasonography images. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(3):540–548. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0811-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Starck M, Bohe M, Fortling B, Valentin L. Endosonography of the anal sphincter in women of different ages and parity. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25(2):169–1776. doi: 10.1002/uog.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rociu E, Stoker J, Eijkemans MJ, Laméris JS. Normal anal sphincter anatomy and age- and sex-related variations at high-spatial-resolution endoanal MR imaging. Radiology. 2000;217(2):395–401. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.2.r00nv13395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valsky DV, Messing B, Petkova R, Savchev S, Rosenak D, Hochner-Celnikier D, Yagel S. Postpartum evaluation of the anal sphincter by transperineal three-dimensional ultrasound in primipa-rous women after vaginal birth and following surgical repair of third-degree tears by the overlapping technique. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29(2):195–204. doi: 10.1002/uog.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dobben AC, Terra MP, Deutekom M, Slors JF, Janssen LW, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J. The role of endoluminal imaging in clinical outcome of overlapping anterior anal sphincter repair in patients with fecal incontinence. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(2):W70–W77. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terra MP, Beets-Tan RG, van der Hulst VP, Deutekom M, Dijkgraaf MG, Bossuyt PM, Dobben AC, Baeten CG, Stoker J. MRI in evaluating atrophy of the external anal sphincter in patients with fecal incontinence. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(4):991–999. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dietz HP, Simpson JM. Levator trauma is associated with pelvic organ prolapse. BJOG. 2008;115(8):979–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guise JM, Boyles SH, Osterweil P, Li H, Eden KB, Mori M. Does cesarean protect against fecal incontinence in primiparous women? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(1):61–67. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0729-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]