Abstract

Objective:

Urgent psychiatric services can provide timely access to ambulatory psychiatric assessment and short-term treatment for patients experiencing a mental health crisis or risk of rapid deterioration requiring hospitalization, yet little is known about how best to organize mental health service delivery for this population. Our scoping review was conducted to identify knowledge gaps and inform program development and quality improvement.

Method:

We searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Embase, and EBM Reviews for English-language articles, published from January 1993 to June 2014, using relevant key words and subject headings. Reverse and forward citations were manually searched using reference lists and Google Scholar. Articles were included if they described programs providing ambulatory psychiatric assessment (with or without treatment) within 2 weeks of referral.

Results:

We identified 10 programs providing urgent psychiatric services. Programs targeted a diagnostically heterogeneous population with acute risks and intensive needs. Most programs included a structured process for triage, strategies to improve accessibility and attendance, interprofessional staffing, short-term treatment, and efforts to improve continuity of care. Despite substantial methodological limitations, studies reported improvements in symptom severity, distress, psychosocial functioning, mental health–related quality of life, subjective well-being, and satisfaction with care, as well as decreased wait times for post-emergency department (ED) ambulatory care, and averted ED visits and admissions.

Conclusions:

Urgent psychiatric services may be an important part of the continuum of mental health services. Further work is needed to clarify the role of urgent psychiatric services, develop standards or best practices, and evaluate outcomes using rigorous methodologies.

Keywords: review, ambulatory care, outpatients, community mental health services, crisis intervention, mental health services, mental disorders, emergency services, psychiatric, urgent psychiatric services, mental health crisis

Abstract

Objectif :

Les services psychiatriques d’urgence peuvent offrir un accès en temps opportun à une évaluation psychiatrique ambulatoire et à un traitement à court terme aux patients qui traversent une crise de santé mentale ou un risque de détérioration rapide nécessitant une hospitalisation, et pourtant, nous en savons très peu sur la meilleure façon d’organiser la prestation de services de santé mentale à cette population. Notre étude d’étendue a été menée pour identifier les lacunes des connaissances, et éclairer l’élaboration des programmes et l’amélioration de la qualité.

Méthode:

Nous avons cherché dans les bases de données MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Embase et EBM Reviews des articles en anglais, publiés entre janvier 1993 et juin 2014, à l’aide des mots clés et des sujets pertinents. Les citations inversées et directes ont été recherchées manuellement à l’aide des bibliographies et de Google Scholar. Les articles ont été inclus s’ils décrivaient des programmes offrant une évaluation psychiatrique ambulatoire (avec ou sans traitement) en moins de 2 semaines après l’aiguillage.

Résultats:

Nous avons identifié 10 programmes offrant des services psychiatriques d’urgence. Les programmes visaient une population hétérogène sur le plan diagnostique avec des risques aigus et des besoins intensifs. La plupart des programmes comportaient un processus structuré de triage, des stratégies pour améliorer l’accessibilité et l’assiduité, un personnel interprofessionnel, un traitement à court terme, et des initiatives pour améliorer la continuité des soins. Malgré des limitations méthodologiques substantielles, les études rapportaient des améliorations de la gravité des symptômes, de la détresse, du fonctionnement psychologique, de la qualité de vie liée à la santé mentale, du bien-être subjectif, et de la satisfaction à l’égard des soins, ainsi que des temps d’attente réduits pour les soins ambulatoires post-département d’urgence (DU), et des visites et admissions évitées au DU.

Conclusions:

Les services psychiatriques d’urgence peuvent être une part importante du continuum des services de santé mentale. Il faut plus de recherche pour clarifier leur rôle, établir des normes ou des pratiques exemplaires, et évaluer les résultats à l’aide de méthodologies rigoureuses.

People experiencing mental illness often have difficulties accessing timely ambulatory mental health care and this may contribute to overreliance on the ED for nonemergency problems.1–7 Further, problems with access to outpatient services, and with coordination and continuity of care after use of acute health care service (for example, ED and inpatient hospitalization), contribute to poor clinical outcomes and further acute health service use.4,8,9 These gaps in care represent an overall failure of the health care system to efficiently, seamlessly, and appropriately care for patients.

Urgent psychiatric services provide rapid access to psychiatric assessment and short-term treatment in an outpatient setting for patients with acute mental health needs.10 As an intermediate level of care between community-based services and acute care (for example, ED or inpatient) services, urgent psychiatric care programs may serve the dual roles of prevention of escalation of an urgent situation to an emergency situation, and ongoing assessment and stabilization during a period of sustained urgency after an ED visit or inpatient admission. Regarding the former, the CPA recommends that patients experiencing “clinical conditions that are unstable, with the potential to deteriorate quickly and result in emergency admission”11, p 2 should wait no more than 2 weeks to access psychiatric services after referral from a family physician. Regarding the latter, the APA Task Force on Psychiatric Emergency Services notes that urgent psychiatric services can mitigate the risks associated with diverting patients who visit the ED from admission.12 For people who do not require immediate intervention, urgent care may be more cost-effective than the ED, more capable of providing continuing stabilization, and more likely to ensure that patients are connected to ongoing care as appropriate in the community.12

A growing body of literature describes effective outpatient interventions for specific populations of high-need psychiatric patients, such as frequent ED users13 or discharged psychiatric inpatients.14 However, in reality, many urgent care programs serve heterogeneous populations from multiple referral sources, raising the question of how such programs should be organized to deliver high-quality interventions. Crisis-oriented ambulatory mental health services may meet a need for rapid access to high-intensity services, but these models of care, and their outcomes, are infrequently reported in the literature, leaving a gap regarding evidence-based best practices or standards. We conducted a scoping review of the literature on models of care for urgent psychiatric care programs to guide program development, quality improvement, and program evaluation, and to identify further scholarly work that is needed to develop this field.

Clinical Implications

Urgent psychiatric services may address gaps in continuity of care between acute and ambulatory care services.

These programs have the potential to reduce avoidable acute care use.

Further research is needed to establish best practices or standards for urgent care programs and assess outcomes and costs.

Limitations

The lack of a consistent definition and nomenclature for urgent psychiatric services may affect the comprehensiveness of our literature search.

Existing program evaluations lack methodological rigour and thus preclude causal inferences regarding program effectiveness.

The review is limited to the published literature.

Methods

We identified programs designed to provide rapid access to psychiatric assessment in an outpatient setting, whether accompanied by treatment or not, and described the structures, processes, and outcomes of these programs.

Search Strategy

We searched the databases MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Embase, and EBM Reviews (including the Cochrane Library) for English-language articles published from January 1993 to June 2014. We used a combination of key words and subject headings for 3 main search themes: urgent, psychiatric, and service. For urgent and psychiatric, we included the following key words: acute, urgent, crisis, crises, mental*, and psychiatr* and the subject headings: emergency services psychiatric, psychiatric emergencies, mental patient, and psychiatric patients. For service, we included the following key words: care, service*, clinic*, healthcare, health care, triage, outpatient*, ambulatory, referral*, consult*, centre*, center*, and program, and we excluded the subject headings: inpatient and hospitalization.

All articles were screened by a single reviewer. If the inclusion or exclusion of an article required difficult judgment at either the title and abstract screening stage or the full-text article screening stage, 2 reviewers screened and discussed the article. Reverse and forward citations were reviewed for articles included after full-text screening, using reference lists and Google Scholar.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included published studies and articles that described a specific program that met the following criteria, regardless of study design or outcomes reported: designed to provide rapid access to psychiatric assessment in an outpatient setting, that is, within 2 weeks of referral from hospital, primary care, or community, or self-referral; providing only assessment or both assessment and treatment; staffed by physicians and (or) other mental health clinicians (for example, nursing, psychology, or social work); based in hospital or community settings; and caring for either pediatric or adult populations.

We excluded programs that were designed to provide unscheduled intervention in the ED (that is, emergency services) or to provide intervention within more than 2 weeks of referral (that is, nonurgent services). We also excluded outpatient programs that relied heavily on hospitalization, residential care, or home treatment teams.

These criteria were developed iteratively, based on increasing familiarity with the literature.15

Data Analysis

We extracted data according to Donabedian’s framework for quality of care, whereby health care delivery can be described in terms of the structure, processes, and outcomes of care.16 Structures represent the conditions under which health care is provided, including program parameters, staffing, and funding. Processes of care entail provider and program activities, such as triage, wait times, treatments, and referrals. Outcomes are changes in people and populations that are attributable to health care, including individual and health system outcomes.

Results

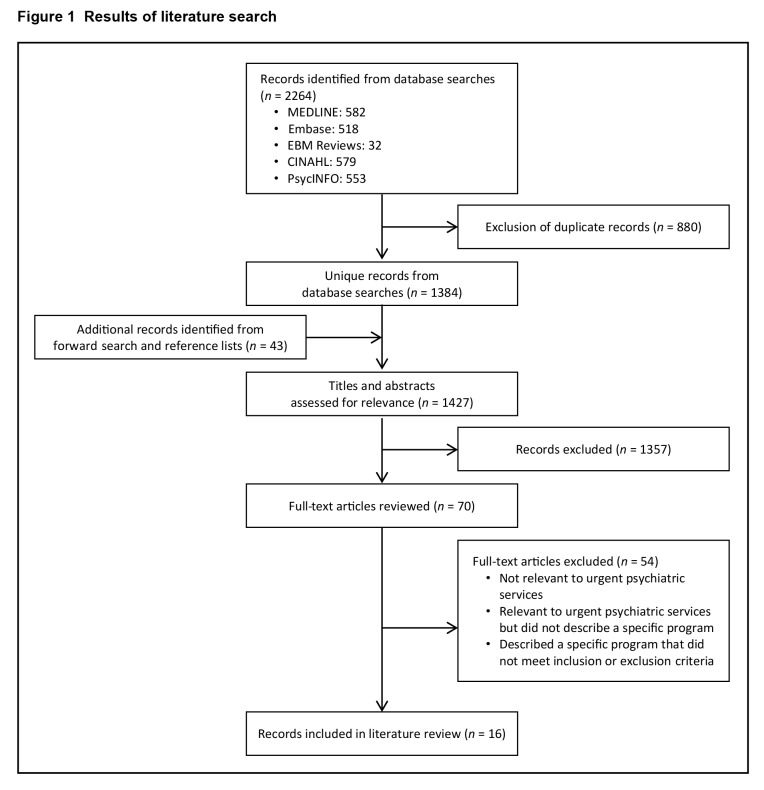

Database searches yielded 1384 unique records, and forward searching and a review of reference lists yielded an additional 43 records. After screening 1427 titles and abstracts and reviewing 70 full-text articles, 16 articles were included in our reference list (Figure 1). The 16 articles described 10 unique urgent psychiatric care programs, of which 7 were hospital-based and 5 were Canadian (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Results of literature search

Table 1.

Urgent psychiatric care programs identified in the literature

|

Table 2 summarizes key aspects of structure and process and Table 3 summarizes outcomes, where reported, for the 10 programs identified, with further details described in the text.

Table 2.

Structures and processes of urgent psychiatric care programs

| Urgent psychiatric care program | Location | Program model | Staffing | Referral sources | Hours of operation | Target wait times,a days | Actual wait times | Episode of care | Services offered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid Response Outpatient Team17,18 | Hospital— outpatient MH | Dedicated clinic | Psychiatry, nursing, social work | Hospital ED | NR | 3 | 6 days (median) | 10 visits (median), 4.5 months (median) | Assessment, treatment (pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy) |

| Rapid Response Model19 | Hospital— outpatient MH | Dedicated clinic | Psychiatry | Hospital ED, family MDs, community (schools) | Weekday daytime | 2 | NR | 1 visit | Assessment |

| Urgent Consultation Clinic10 | Hospital— outpatient MH | Dedicated clinic | Nursing, psychiatry, psychology, social work | Hospital ED, PES, psychiatric inpatient, medical or surgical unit | Weekday daytime | 10 | 12 days (median) | 1 to 8 visits, up to 3 months | Assessment, treatment (pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy) |

| Urgent Followup Clinic25 | Hospital— outpatient MH | Dedicated clinic | Nursing, psychiatry, psychology | Hospital ED | Weekday daytime | 7 | NR | 1 to 6 visits | Assessment, treatment (pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy) |

| Pediatric Crisis Clinic29,30 | Hospital— outpatient MH | Dedicated clinic | Psychiatry | Hospital ED | Weekday daytime | 3 | NR | 1 visit | Assessment |

| ED-based MHNP Outpatient Service21,26,27,31,32 | Hospital— ED | Dedicated clinic | Nursing | Hospital ED | Weekday daytime | NR | 6.4 days (mean) | 1 to 5 visits | Assessment, brief psychotherapy, psychoeducation |

| Interim Crisis Clinic20 | Hospital— PES | Dedicated clinic | Psychiatry, psychology | Hospital PES | Weekday daytime | 7 | NR | 1 to 6 visits | Assessment, treatment (pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, psychoeducation) |

| Mental Health Urgent Care Service22 | Community —health centre | Dedicated clinic | Nursing, psychiatry | Family MD, self-referral | Extended hours | <1 | 5 hours (maximum) | 1 visit | Assessment (psychiatric and physical health), treatment (psychosocial support, pharmacotherapy recommendations) |

| Quick Response Team24 | Community —MH | Triage process only | Nursing | Family MD, community MH, self-referral | Weekday daytime | 1 | NR | Triage only | Triage only |

| Urgent Assessment Service23 | Community —MH | Dedicated clinic | Nursing, psychiatry | Family MD, community MH, self-referral, hospital MD | Weekday daytime | 7 | NR | 3 visits (mean) | Assessment, treatment (pharmacotherapy, psychosocial support) |

Time from referral to initial in-person appointment. ED = emergency department; MD = medical doctor; MH = mental health; MHNP = mental health nurse practitioner; NR = not reported

Table 3.

Outcomes of urgent psychiatric care programs

| Urgent psychiatric care program | Evaluation design | Outcomes reported |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid Response Outpatient Team17,18 | Randomized controlled trial |

|

| Rapid Response Model19 | Interrupted time series |

|

| Urgent Consultation Clinic10 | Pre–post, no control group |

|

| Urgent Followup Clinic25 | Post-only, no control group |

|

| Pediatric Crisis Clinic29,30 | Post-only, no control group |

|

| ED-based Mental Health Nurse Practitioner Outpatient Service21,26,27,31,32 | Pre–post, no control group |

|

| Interim Crisis Clinic20 | Post-only, no control group |

|

| Mental Health Urgent Care Service22 | Post-only, no control group |

|

| Quick Response Team24 | Post-only, no control group |

|

| Urgent Assessment Service23 | Post-only, no control group |

|

Structural Aspects of Urgent Psychiatric Care

Patient Population and Referral Sources

The target populations for the 10 programs were diagnostically heterogeneous populations characterized by their inability to safely await routine ambulatory care, for example owing to acute risk of suicide, self-harm, or clinical deterioration requiring hospitalization. Only one program limited referrals to patients with suicidality only.17,18

Hospital-based programs most commonly accepted referrals for patients assessed in the ED or PES who were not admitted to hospital, and patients discharged from inpatient psychiatry who had no community psychiatric follow-up.10 Therefore, appraisal of risk for these programs considered not only the clinical presentation but also the gaps in the mental health care system that render people in crisis vulnerable to continuing high levels of distress and adverse outcomes. In contrast to the 3 community-based programs, only 1 hospital-based program additionally accepted referrals from primary care and other community settings.19

Physical and Organizational Configuration

Hospital-based urgent psychiatric care programs were all located within the hospital’s outpatient mental health service, with the exceptions of the Interim Crisis Clinic in New York City,20 based in a comprehensive PES, and the MHNP Outpatient Service in Sydney,21 based in the hospital ED. Community-based programs were located within general or mental health-specific community health centres.22–24

Staffing

Programs were typically staffed by health care providers from several disciplines (for example, psychiatrists, nurses, psychologists, and [or] social workers). The rationale for a multidisciplinary approach was rarely explicitly stated; however, it may be intended to expand the volume of patients who could be seen (for example, through joint assessment, either in a single appointment or asynchronously) and (or) to expand the comprehensiveness of services (for example, psychotherapies).10,22,23 Few programs specifically described how providers of different disciplines interfaced in the care of patients. Thus it is unclear whether care was truly interprofessional and team-based (as opposed to multidisciplinary), how roles were defined and negotiated, how communication occurred, and how clinical deterioration and (or) risks were handled. Scope of practice appeared to be a common concern, particularly in the nursing literature.22,24–26 Kowal et al10 described how The Ottawa Hospital formally modified professional roles to use the full scope of each team member’s practice for the Urgent Consultation Clinic.

Processes of Urgent Psychiatric Care

Response Time

Most hospital-based programs aimed to see patients for their first appointment within 7 days (range 2 to 10 days), as did the 1 community-based program that had a similar model of assessment and brief treatment.23 Three programs reported actual wait times for first appointments, which were 2 to 3 days longer than their target wait times and ranged from 6 to 12 days.10,17,27 One community program was a walk-in service22 and 1 community program provided triage only.24

Triage

In most programs, a nurse triaged patients in person and (or) over the telephone.

Treatment

Some crisis-oriented mental health services may be designed to provide rapid evaluation and referral, and others may aim to provide brief treatment in the least restrictive setting possible, as part of a continuum of care.28 Four urgent psychiatric care programs provided a single visit for assessment and referral,19,22,24,29,30 in keeping with the former model. The 6 other urgent psychiatric care programs were consistent with the latter model, providing assessment and a brief episode of care, with a limited number of visits (up to 6 or 8 visits10,20,25) or time period (up to 3 months10).

For those programs providing brief episodes of care, objectives of treatment included continuing assessment beyond the cross-sectional view afforded in the ED (for example, risk assessment, needs assessment, and diagnostic clarification), safety planning, addressing the immediate precipitants of the crisis, building skills for coping, distress tolerance, and self-care, strengthening support networks in the community, and transitioning to either crisis resolution or to ongoing formal care. In most programs, treatment approaches were pragmatic and flexible, rather than diagnosis-based or preordained.10,17,20,23,25,26 Clinician activities commonly included patient and (or) family psychoeducation,20,21,26,27,31,32 brief psychotherapy10,17,18,20–23,25–27,31,32 (cognitive, behavioural, dynamic, mindfulness, solution-focused, or supportive), initiation or adjustment of pharmacotherapy,10,17,18,20,22,23,25 and referrals to community supports or professional care.10,17,18,20–23,25–27,31,32

Coordination and Continuity of Care

Continuity of care can be conceptualized as patients “experiencing care over time as coherent and linked,”33, p i and may rest on the continuity of therapeutic relationships, the accumulation, transfer, and use of knowledge about patients in their care, and a smooth and flexible progression through accessible, consistent, and coordinated services.34–36

Each of the urgent psychiatric care programs we identified implemented elements of care continuity in unique and particular ways. All programs focused on the timeliness of care. Several programs aimed to improve accessibility of services by eliminating barriers associated with referral and scheduling (for example, enabling ED or PES staff to book urgent outpatient appointments directly),19,20 accepting referrals by phone and responding within 1 hour,24 or offering walk-in services.22 Some programs explicitly described efforts to liaise with other providers (for example, to promote informational continuity regarding the patient) through written assessment notes and discharge summaries19,22,25; in other programs, this was not described, but may have been assumed. All programs discussed referrals for ongoing care, with a few programs particularly emphasizing engagement of a wide range of supports (for example, community agencies, peer support, housing and social services, the justice system, child protection, and schools), and monitoring to ensure successful referrals and connections.24,25,29,31,32

Outcomes of Urgent Psychiatric Care

The urgent psychiatric care programs identified in the literature have not been rigorously evaluated; with 2 exceptions, most studies reporting outcome data were noncontrolled pre–post or post-only designs, with limited ability to draw causal inferences regarding program effectiveness. Parker et al19 used an interrupted time series study design, taking advantage of the Rapid Response Model program’s introduction, withdrawal, and resumption at 2 different sites. Greenfield et al17 conducted an RCT, in which on-call psychiatrists who saw suicidal adolescents in the hospital ED had access to the Rapid Response Outpatient Team if they were part of the intervention group, and did not if they were part of the usual care group.

Clinical Outcomes

Overall, programs reported improvements in clinical outcomes, including clinician-assessed mental health and psychosocial functioning10 and various patient-reported clinical outcomes, including: improvements in levels of distress,22,27 self-efficacy,27 mental health symptom severity,10 and mental health–related quality of life and subjective well-being.10 However, in the RCT of the Rapid Response Outpatient Team, Greenfield et al17 reported no between-group differences in overall functioning (measured by the Children’s Global Assessment Scale) or levels of suicidality (measured by the Spectrum of Suicidal Behavior Scale) for the intervention group (n = 158), compared with the usual care group (n = 128), at 6-month follow-up.

Health Services Use

The literature also reported improvements in patterns of health services access and use. Parker et al’s19 interrupted time series study found that the Rapid Response Model was associated with decreased referrals to on-call psychiatry and decreased overnight inpatient admissions. In Greenfield et al’s17 RCT, the rate of initial hospitalization was 11% for patients in the Rapid Response Outpatient Team intervention group, compared with 40% for the usual care group (P < 0.001). However, during a 6-month period of follow-up that recorded hospitalizations at the study hospital and nearby hospitals, there were no significant differences in the number of cumulative hospitalized days (5.4, compared with 5.5, days, P = 0.97).18

In less rigorous post-only evaluations using patient and staff surveys, patients reported averted ED visits,22 and ED staff and PES staff reported averted hospital admissions.25 Anecdotally, The Ottawa Hospital reported that outpatient psychiatry wait times improved from 4 to 6 weeks to 12 days, on average, with a new program model that included the introduction of the Urgent Consultation Clinic.10

Costs

Latimer et al18 conducted a cost-effectiveness analysis for the RCT, comparing the Rapid Response Outpatient Team to usual care. Regarding the costs of resources that were covered by the study hospital, the average cost per patient during the 6-month follow-up period was Can$2114 for the intervention group, which was Can$1886 lower than the average cost per patient for the usual care group, but not statistically significant (P = 0.11). Regarding overall costs to the health care system (that is, including care at other hospitals, physician services, publicly insured medications and out-of-pocket health care expenditures), the average cost per patient for the intervention group was $10 785, which was $991 lower than the usual care group, which was also not statistically significant (P = 0.67). The difference in the study hospital and health care system costs was mainly because the intervention group’s lower initial admission rate at the study hospital was offset by admissions at other hospitals.

Discussion

The findings of our literature review are limited by several potential sources of bias. The scope of urgent psychiatric services bounding our search strategy was subject to our own biases, as there is no consistent definition of urgent psychiatric services in the literature, and relevant studies may have been inadvertently excluded from the search strategy owing to heterogeneous nomenclature. Outcome evaluations lacked methodological rigour, compromising the ability to generate causal inferences about the effectiveness of programs or to disaggregate the effects of program components. Few published studies reported neutral outcomes, and no studies reported negative outcomes, suggesting publication bias. Finally, variation in programs, metrics, and reporting limited our review to a narrative approach. Nevertheless, in the absence of evidence-based practices and (or) widely accepted standards of care, our scoping literature review identifies common elements related to the structures and processes of care, and points to knowledge gaps for future inquiry.

Our findings point to a striking absence of evidence to guide the widespread practice of providing urgent psychiatric care. Programs may be born of necessity (for example, to combat the problems associated with delayed or absent aftercare post-acute presentation) and may be organized based on locally available human and other resources, lacking a firm foundation in evidence and evaluation to guide implementation and sustainability over time. The liberal propagation of urgent psychiatric care programs based on sparse evidence suggests that these programs may play an important role within the continuum of mental health services; however, it is vital that the evidence gaps in this area be addressed. One challenge in future evaluations will be to reconcile the need for high-quality studies that enable causal inferences (for example, RCTs) with the ethical issues involved in withholding what has already become usual care. Well-designed, quasi-experimental studies and comparative effectiveness research may aid in this endeavour.

According to the studies reviewed here, and consistent with the CPA11 and APA12 definitions, the target population for urgent psychiatric services is based on patient risks and vulnerabilities irrespective of diagnosis. Thus the urgent care population may be diagnostically heterogeneous with frequent comorbidity (including addictions and medical problems), at high risk of harm to themselves and (or) others, and vulnerable regarding socioeconomic status and relations. They may receive care from multiple health and social service providers and organizations concurrently and sequentially and thus have a high need for care continuity across service sectors and over time, yet they may also experience significant difficulty navigating the mental health system.

Unfortunately, there is a dearth of empirical evidence to determine clinically appropriate wait times for patients being discharged from the ED. The CPA’s proposed benchmark of 2 weeks references referrals from primary care, not acute care settings.11 In the United States, quality indicators for follow-up after acute care are geared toward discharged inpatients (for example, within 7 days for patients with schizophrenia, within 30 days for patients with depression).37,38 The hospital-based urgent care programs we reviewed have set targets in the range of 2 to 10 days, and those programs reporting actual wait times provided initial appointments within 6 to 12 days on average. None of the programs specifically examined whether their chosen wait times impacted on individual or health system outcomes.

Triage may fulfill key functions, not only in ensuring people are provided care in accordance with their level of risk and type of needs but also in ensuring program sustainability and coherence.39–41 The APA recommends that triage must be accompanied by clear criteria by which a person could be referred to an alternative setting, as well as a process for ensuring care continuity and successful linkages.12

The failure to more thoroughly explore interprofessionalism in the urgent psychiatric care context may represent a missed opportunity to address its inherent advantages and challenges. Interprofessional teams may generate more nuanced assessments of risks and needs, more accurate and useful formulations regarding the nature and precipitants of a person’s crisis, and more effective tailoring of services to pragmatically support crisis resolution. The challenge lies in building the interpersonal processes, programmatic structures, and leadership support required for staff to work in modified or expanded scopes of practice that safely, flexibly, and comprehensively meet the needs of people in crisis.

Case management services were scarcely mentioned in the literature on urgent psychiatric services. This is surprising given the robust literature to support its effectiveness for frequent users of the ED13,42–44 and for transitional care after inpatient discharge.14,45–48 Case managers may play a key role in urgent psychiatric care programs, optimizing engagement through active outreach, and promoting connections in the community.

Urgent psychiatric care programs can promote care continuity at a critical juncture (for example, after an acute presentation to the ED) for people who lack necessary supports and who may have heightened difficulty navigating the mental health system. Indeed, this is a central objective of urgent psychiatric care programs, yet programs have adopted idiosyncratic approaches to achieving this aim. There appears to be little consistency in programs’ eligibility criteria, response times, appointment accessibility, or treatment offerings. Moreover, problems with inaccessible, fragmented, and niche outpatient mental health services both fuel the need for urgent care (that is, crisis presentations) and pose a threat to the sustainability of urgent care as disposition can be challenging. Programs may feel obligated to extend urgent care for longer periods of time to ensure smooth transitions, yet may be unable to sustain the volume of care for people transitioning between crisis and longer-term services.

Solutions will require attention to the organization and delivery of both urgent and nonurgent ambulatory mental health care. For example, acute home treatment teams are a promising alternative to inpatient admission for people in crisis,49 integrated or collaborative care models can improve access to nonurgent care,50–52 and modifications to reimbursement models could support these evolving modes of practice.53 As a starting point, we recommend a more data-driven approach to designing urgent psychiatric services, including identifying priority populations, establishing clinically appropriate wait times, rigorously evaluating outcomes, and drawing connections between specific processes of care and clinical and health system outcomes. There is a tendency to develop programs based on local health care structures and resources; a more evidence-based approach is needed to better meet the needs of people in crisis.12

Conclusion

Urgent psychiatric services provide rapid access to multidisciplinary mental health care in an outpatient setting for people in crisis. These programs form an important part of the continuum of acute and ambulatory care, promoting care continuity and potentially reducing preventable use of acute care services. Thoughtfully structured and robustly staffed programs can care for complex, high-risk patients. However, the amount and quality of published literature evaluating urgent psychiatric services is exceedingly limited. The program components identified in this literature review suggest the basic building blocks for urgent psychiatric services, yet further research is needed to develop evidence-based standards of care.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Mental Health and Addictions Acute Care Alliance (Toronto) for their support and funding of this research. We thank Carolyn Ziegler, Information Specialist with the Health Sciences Library, Li Ka Shing International Healthcare Education Centre at St Michael’s Hospital, for her assistance with the search strategy.

Abbreviations

- APA

American Psychiatric Association

- CPA

Canadian Psychiatric Association

- ED

emergency department

- MHNP

mental health nurse practitioner

- PES

psychiatric emergency service

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

References

- 1.Heggestad T. Operating conditions of psychiatric hospitals and early readmission—effects of high patient turnover. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103(3):196–202. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson EA, Maruish ME, Axler JL. Effects of discharge planning and compliance with outpatient appointments on readmission rates. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(7):885–889. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.7.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prince JD. Practices preventing rehospitalization of individuals with schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194(6):397–403. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000222407.31613.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madi N, Zhao H, Li JF. Hospital readmissions for patients with mental illness in Canada. Healthc Q. 2007;10(2):30–32. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2007.18818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, et al. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(8):886–891. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.8.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steele LS, Durbin A, Sibley LM, et al. Inclusion of persons with mental illness in patient-centred medical homes: cross-sectional findings from Ontario, Canada. Open Med. 2013;7(1):e9–e20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vandyk AD, Harrison MB, VanDenKerkhof EG, et al. Frequent emergency department use by individuals seeking mental healthcare: a systematic search and review. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2013;27(4):171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions [Internet] Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2006. [cited 2014 Jun 3]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19830/. Quality Chasm Series. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, et al. Closing the quality gap: a critical analysis of quality improvement strategies (volume 7: care coordination) [Internet] Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. [cited 2014 Jun 3]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44015/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kowal J, Swenson JR, Aubry TD, et al. Improving access to acute mental health services in a general hospital. J Ment Health. 2011;20(1):5–14. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2010.492415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Psychiatric Association (CPA) Wait time benchmarks for patients with serious psychiatric illnesses [Internet] Ottawa (ON): CPA; 2006. [cited 2014 Jun 3]. Available from: http://www.cpa-apc.org/media.php?mid=585. [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychiatric Association (APA) Task Force on Psychiatric Emergency Services. Report and recommendations regarding psychiatric emergency and crisis services [Internet] Arlington (VA): APA; 2002. [cited 2014 Jun 3]. Available from: http://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Learn/Archives/tfr2002_EmergencyCrisis.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Althaus F, Paroz S, Hugli O, et al. Effectiveness of interventions targeting frequent users of emergency departments: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(1):41–52. e42. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vigod SN, Kurdyak PA, Dennis C-L, et al. Transitional interventions to reduce early psychiatric readmissions in adults: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(3):187–194. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.115030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donabedian A. Selecting approaches to assessing performance In: Donabedian A An introduction to quality assurance in health care. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenfield B, Larson C, Hechtman L, et al. A rapid-response outpatient model for reducing hospitalization rates among suicidal adolescents. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(12):1574–1579. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Latimer EA, Garièpy G, Greenfield B. Cost-effectiveness of a rapid response team intervention for suicidal youth presenting at an emergency department. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(6):310–318. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker KCH, Roberts N, Williams C, et al. Urgent adolescent psychiatric consultation: from the accident and emergency department to inpatient adolescent psychiatry. J Adolesc. 2003;26(3):283–293. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(03)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simakhodskaya Z, Haddad F, Quintero M, et al. Innovative use of crisis intervention services with psychiatric emergency room patients. Prim Psychiatry. 2009;160(9):60–65. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wand T, White K, Patching J. Realistic evaluation of an emergency department-based mental health nurse practitioner outpatient service in Australia. Nurs Health Sci. 2011;13(2):199–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Southern L, Leahey M, Harper-Jaques S, et al. Integrating mental health into urgent care in a community health centre. Can Nurse. 2007;103(1):29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crawford MJ, Kohen D, Dalton J. Evaluation of a community based service for urgent psychiatric assessment. Psychiatr Bull. 1996;20(10):592–595. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tummey R. A collaborative approach to urgent mental health referrals. Nurs Stand. 2001;15(52):39–42. doi: 10.7748/ns2001.09.15.52.39.c3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Hearne MA, Quint FL, Rosenbaum L. Hospital-based urgent mental health care. Can Nurse. 2014;110(1):22–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wand T, White K, Patching J, et al. Introducing a new model of emergency department-based mental health care. Nurse Res. 2010;18(1):35–44. doi: 10.7748/nr2010.10.18.1.35.c8046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wand T, White K, Patching J, et al. Outcomes from the evaluation of an emergency department-based mental health nurse practitioner outpatient service in Australia. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2012;24(3):149–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2011.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janssens A, Hayen S, Walraven V, et al. Emergency psychiatric care for children and adolescents: a literature review. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(9):1041–1050. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182a393e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J, Korczak D. Emergency physician referrals to the pediatric crisis clinic: reasons for referral, diagnosis and disposition. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(4):297–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee J, Korczak D. Factors associated with parental satisfaction with a Pediatric Crisis Clinic (PCC) J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(2):118–127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wand T, White K, Patching J, et al. An emergency department-based mental health nurse practitioner outpatient service: part 1, participant evaluation. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2011;20(6):392–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2011.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wand T, White K, Patching J, et al. An emergency department-based mental health nurse practitioner outpatient service: part 2, staff evaluation. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2011;20(6):401–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2011.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reid R, Haggerty J, McKendry R. Defusing the confusion: concepts and measures of continuity of healthcare. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waibel S, Henao D, Aller M-B, et al. What do we know about patients’ perceptions of continuity of care? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(1):39–48. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzr068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dewa CS, Jacobson N, Durbin J, et al. Examining the effects of enhanced funding for specialized community mental health programs on continuity of care. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2010;29:23–40. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson S, Prosser D, Bindman J, et al. Continuity of care for the severely mentally ill: concepts and measures. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1997;32(3):137–142. doi: 10.1007/BF00794612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hermann RC, Palmer RH. Common ground: a framework for selecting core quality measures for mental health and substance abuse care. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(3):281–287. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Committee for Quality Assurance Follow-up after hospitalization for schizophrenia (7- and 30-day) [Internet] Washington (DC): National Quality Forum; 2014. [cited 2014 Jun 3]. Available from: http://www.qualityforum.org/QPS/1937. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burbach FR. GP referral letters to a community mental health team: an analysis of the quality and quantity of information. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 1997;10(2):67–72. doi: 10.1108/09526869710166969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cubbin S, Llewellyn-Jones S, Donnelly P. How urgent is urgent? Analysing urgent out-patient referrals to an adult psychiatric service. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2000;4(3):233–235. doi: 10.1080/13651500050518136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hilton C, Bajaj P, Hagger M, et al. What should prompt an urgent referral to a community mental health team? Ment Health Fam Med. 2008;5(4):197–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiss A, Schechter M, Chang G. Case management for frequent emergency department users. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(7):715–716. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crane S, Collins L, Hall J, et al. Reducing utilization by uninsured frequent users of the emergency department: combining case management and drop-in group medical appointments. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(2):184–191. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.02.110156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.[No authors listed] ED navigators steer patients with social, financial, or behavioral health needs to appropriate resources. ED Manag. 2012;24(12):137–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kasprow WJ, Rosenheck RA. Outcomes of critical time intervention case management of homeless veterans after psychiatric hospitalization. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(7):929–935. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.7.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dixon L, Goldberg R, Iannone V, et al. Use of a critical time intervention to promote continuity of care after psychiatric inpatient hospitalization. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):451–458. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reynolds W, Lauder W, Sharkey S, et al. The effects of a transitional discharge model for psychiatric patients. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2004;11(1):82–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2004.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Forchuk C, Martin M-L, Chan YL, et al. Therapeutic relationships: from psychiatric hospital to community. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2005;12(5):556–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2005.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carpenter RA, Falkenburg J, White TP, et al. Crisis teams: systematic review of their effectiveness in practice. Psychiatrist. 2013;37(7):232–237. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Butler M, Kane RL, McAlpine D, et al. Integration of mental health/ substance abuse and primary care. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kates N, Mazowita G, Lemire F, et al. The evolution of collaborative mental health care in Canada: a shared vision for the future. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(5 Insert 1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wait Time Alliance . Time to close the gap: report card on wait times in Canada (2014) [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Wait Time Alliance; 2014. [cited 2014 Jun 3]. Available from: http://www.waittimealliance.ca/wta-reports/2014-wta-report-card/. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kurdyak PA, Stukel T, Goldbloom D, et al. Universal coverage without universal access: a study of psychiatrist supply and practice patterns in Ontario. Open Med. 2014;8(3):87–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]