Abstract

Growing evidences show that matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP1) plays important roles in tumorigenesis and cancer metastasis. The interactions between MMP1−1607 1G>2G polymorphism and risk of gastric cancer (GC) have been reported, but results remained ambiguous. To determine the association between MMP1−1607 1G>2G polymorphism and risk of GC, we conducted a meta-analysis and identified the outcome data from all the research papers estimating the association between MMP1−1607 1G>2G polymorphism and GC risk, which was based on comprehensive searches using databases such as PubMed, Elsevier Science Direct, Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). The fixed-effects model was used in this meta-analysis. Data were extracted, and pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. In this meta-analysis, six studies involving 1,377 cases and 1,543 controls were included. We identified the significant association between MMP1−1607 1G>2G polymorphism and GC risk for allele model (OR =1.05; 95% CI, 1.01−1.08), for dominant model (OR =1.11; 95% CI, 1.08−1.15), and for recessive model (OR =1.06; 95% CI, 0.98−1.14). In summary, our analysis demonstrated that MMP1−1607 1G>2G polymorphism was significantly associated with an increased risk of GC.

Keywords: MMP1, gene polymorphisms, gastric cancer

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fourth most common cancer and second leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide.1 The mechanism of gastric carcinogenesis remains elusive. Environmental and genetic factors possibly play a role in the etiology of the disease.2,3 However, these risk factors cannot fully explain the development of GC, since only a minority of exposed population finally developed GC, indicating possible interplay between risk factors and personal background including genetic susceptibility.4 Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a group of proteolytic enzymes involved in physiological and pathological extracellular matrix processing, capable of degrading essentially all extracellular matrix components.5,6

MMPs are divided into five structural families, including collagenases, gelatinases, stromelysins, matrilysins, and membrane-type MMPs. More evidence indicates that many MMPs are involved in tumorigenesis by modulating cell proliferation, apop-tosis, and angiogenesis.7 MMP1, located on 11q22.3, is one member of the MMP family and degrades interstitial collagen types I, II, and III. The expression level of MMP1 gene is at low level in normal cells under physiological conditions;8,9 however, MMP1 expression is dramatically increased in many malignancies.5,10 It has been reported that the promoter of MMP1 can regulate MMP1 gene transcription, in which there is a functional single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), MMP1−1607 1G>2G (rs1799750),11,12 which contains a guanine insertion/deletion polymorphism at position −160713 and leads to higher expression of MMP1. In the current study, we performed a meta-analysis of hospital-based studies to determine the association between the MMP1−1607 1G>2G polymorphism and GC risk.

Materials and methods

Study strategy

A systematic computerized search in all the electronic databases that could search for literatures, including PubMed, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), EMBASE and Elsevier Science Direct etc, was conducted to collect all case-control studies evaluating MMP1 and GC in humans published until August 2014. The search was developed without any language restriction and searching for the following terms: (matrix metalloproteinase-1 OR MMP1), (polymorphism OR polymorphisms OR variant OR variants OR genotype), and (cancer OR carcinoma OR neoplasm). To expand our research, we also performed the search in the CNKI database using terms in Chinese, such as MMP1, gastric cancer risk OR GC risk, and polymorphism. The references for all identified publications were hand-searched for additional studies.

Statistical methods

We used odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to measure the strength of association between MMP1−1607 1G>2G polymorphism and GC risk. Pooled ORs and 95% CIs were calculated for an allele mode, a dominant model (variant homozygote + heterozygote vs wild-type homozygote), and a recessive model (variant homozygote vs heterozygote + wild-type homozygote).

Then, we assessed an estimate of potential publication bias using the funnel plot, in which the standard error of log (SEL) of every study was plotted against its log (OR), and an asymmetric plot indicated a potential publication bias. We assessed funnel plot asymmetry using Egger’s linear regression test, a linear regression method of evaluating funnel plot asymmetry on the natural logarithm scale of the OR. The significance of the intercept was determined using the t-test suggested by Egger, and P<0.05 was considered representative of statistically significant publication bias. All of the statistical tests were performed using STRATA version 12.0 (StrataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Data extraction

The following basic data were collected from the studies that met the inclusion criteria: first author’s name, tumor type, year of publication, country, ethnicity of study population, number of cases and controls, and genotyping method. Two independent investigators conducted data extraction work, and they resolved discrepancies through discussion. Study qualities were judged according to the criteria modified from a previously published study14 (Table S1).

Results

Eligible study characteristics

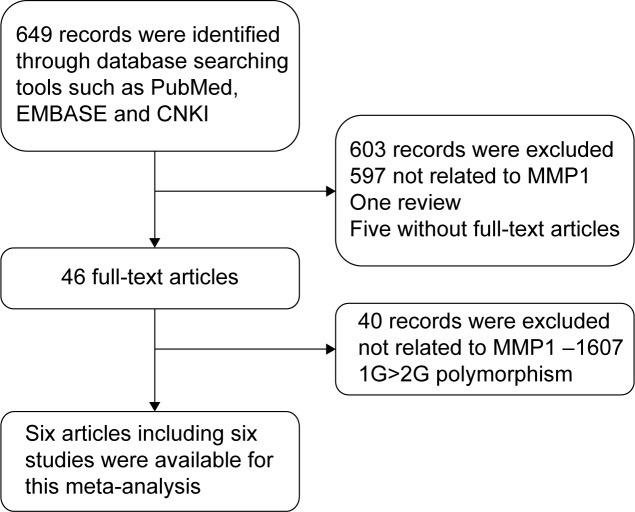

A total of 649 publications, all written in English or Chinese and all extracted from the PubMed, MEDILINE, EMBASE, and CNKI databases, were reviewed. Finally, six articles15–20 containing six studies, including 1,377 GC cases and 1,543 non-cancer controls were included in the current meta-analysis. A flowchart shows the study selection procedure (Figure 1). The main characteristics of the studies are listed in Table 1. Sample sizes and MMP1−1607 1G>2G allele and genotype distributions in the studies considered in the present meta-analysis are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection procedure of this meta-analysis.

Abbreviations: EMBASE, Excerpta Medica Database; CNKI, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure; MMP1, matrix metalloproteinase-1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of individual studies included in the current meta-analysis

| First author’s name (year) | Country | Genotype method | Selection/characteristics of cases | Selection/characteristics of controls | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matsumura et al (2004) | Japan | PCR-RFLP | 215 gastric cancer patients, 153 males and 62 females (median age 67.7±11.4 years), including 122 patients with an intestinal type of gastric cancer and 93 patients with a diffuse type | 166 healthy control subjects, 95 males and 71 females | 20 |

| Jin et al (2005) | People’s Republic of China | PCR | 183 patients with gastric cardiac adenocarcinoma, 134 males and 49 females, average age 55.0±10.5 years | 350 healthy individuals, 229 males and 121 females, average age 51.7±10.7 years | 19 |

| Fang et al (2013) | People’s Republic of China | PCR-RFLP | 246 gastric cancer patients, 163 males and 83 females, average age 57.9±11.8 years | 252 normal controls, 167 males and 85 females, average age 58.8±11.2 years | 18 |

| Devulapalli et al (2014) | India | PCR-RFLP | 166 gastric cancer patients, 118 males and 48 females, 82.53% ≥50 years | 202 normal controls, 132 males and 70 females, 62.37% ≥50 years | 16 |

| Dey et al (2014) | India | PCR | 145 gastric cancer patients, 112 males and 33 females, range 42.6–65.8 years | 145 normal controls, 81 males and 64 females, range 34.5–62.5 years | 17 |

| Hua et al (2014) | People’s Republic of China | PCR | 422 gastric cancer patients, 237 males and 185 females, range 42.2±5.6 years | 428 gastric cancer patients, range 43.3±4.6 years | 15 |

Note: Equations show data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Abbreviations: PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism.

Table 2.

Sample sizes and MMP1–1607 1G>2G allele and genotype distributions in the studies considered in the present meta-analysis

| Gene | First author’s name (year) | Cases

|

Controls

|

HWE of control (P-value) | Frequency of 1G allele in controls | Quality* | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2G/2G | 1G/2G | 1G/1G | 2G | 1G | N | 2G/2G | 1G/2G | 1G/1G | 2G | 1G | |||||

| MMP1–1607 | Matsumura et al20 (2004) | 215 | 101 | 88 | 26 | 290 | 140 | 166 | 88 | 61 | 17 | 237 | 95 | Y (0.1953) | 0.713855 | 7 |

| 1G/2G | Jin et al19 (2005) | 183 | 112 | 51 | 20 | 275 | 91 | 350 | 194 | 105 | 51 | 493 | 207 | N (0.0000) | 0.704286 | 7 |

| Fang et al18 (2010) | 246 | 155 | 85 | 6 | 395 | 97 | 252 | 161 | 78 | 13 | 400 | 104 | Y (0.3826) | 0.793651 | 7 | |

| Devulapalli et al16 (2014) | 166 | 46 | 114 | 6 | 206 | 126 | 202 | 50 | 130 | 22 | 230 | 174 | N (0.0000) | 0.569307 | 7 | |

| Dey et al17 (2014) | 145 | 56 | 66 | 23 | 178 | 112 | 145 | 53 | 72 | 20 | 178 | 112 | Y (0.2713) | 0.613793 | 6 | |

| Hua et al4 (2014) | 422 | 186 | 187 | 49 | 559 | 285 | 428 | 158 | 195 | 75 | 511 | 345 | Y (0.5686) | 0.596963 | 7 | |

Note:

Represents the confidence of the study.

Abbreviations: MMP1, matrix metalloproteinase-1; HWE, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium; N, number of subjects.

Quantitative synthesis

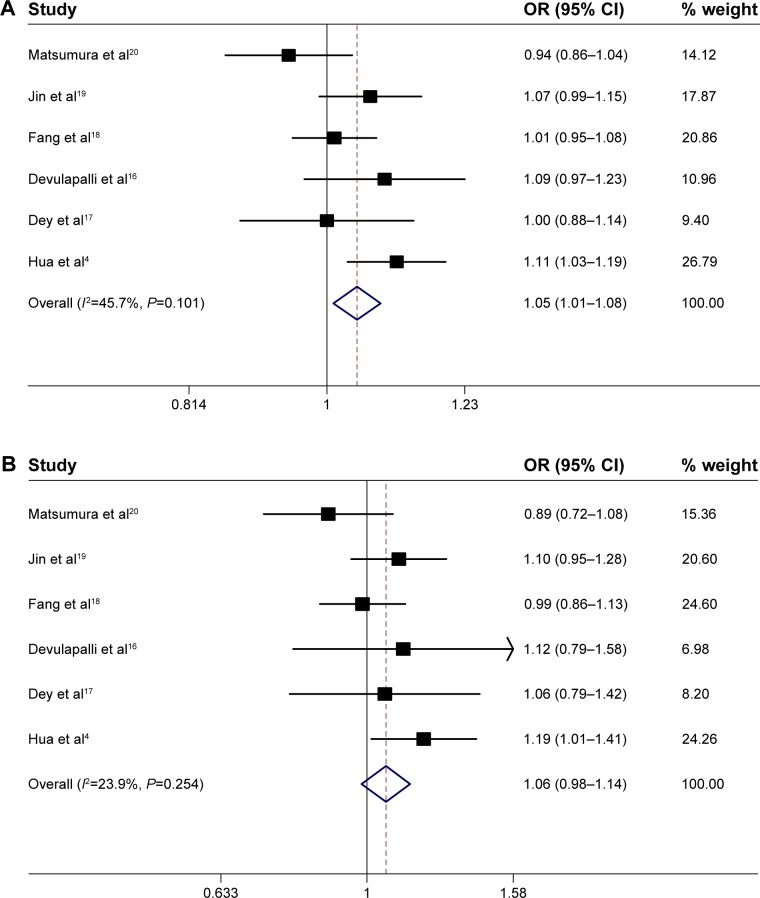

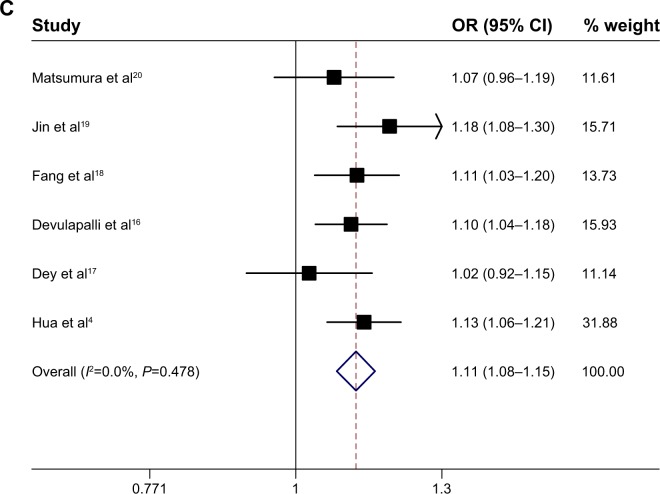

The fixed-effects model is used in the current meta-analysis. The association between the MMP1−1607 1G>2G polymorphism and cancer risk was estimated with the following models: an allele model (2G vs 1G), a dominant model (2G/2G + 1G/2G vs 1G/1G), and a recessive model (2G/2G vs 2G/1G + 1G/1G). The evaluations of the association of MMP1−1607 1G>2G with cancer risk are shown in Table 3. In the allele model (2G vs 1G), the overall pooled effect showed that the 2G allele was associated with an increased overall cancer risk, compared with the 1G allele (OR =1.05; 95% CI, 1.01–1.08) (Figure 2A). In the recessive model (2G/2G vs 2G/1G + 1G/1G), the overall pooled effect showed that the 2G/2G homozygote was not associated with an overall cancer risk, compared with the 2G/2G + 1G/1G homozygote (OR =1.06; 95% CI, 0.98–1.14) (Figure 2B). In the dominant model (2G/2G + 1G/2G vs 1G/1G), the overall pooled effect demonstrated that the 2G/2G + 1G/2G genotypes were associated with a significantly increased overall cancer risk, compared with the 1G/1G homozygote (OR =1.11; 95% CI, 1.08–1.15) (Figure 2C).

Table 3.

Meta-analysis of the association between the studied MMP1 alleles and GC in different populations

| Gene | Genotypes | Group | Fixed-effects model

|

Heterogeneity

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | Z | P | χ2 | I2 (%) | PQ-test | |||

| MMP1–1607 | 2G vs 1G | Total | 1.05 (1.01–1.06) | 2.49 | 0.013 | 9.21 | 45.7 | 0.101 |

| 1G/2G | 2G/2G vs 2G/1G + 1G/1G | Total | 1.06 (0.989–1.14) | 1.52 | 0.129 | 6.57 | 23.9 | 0.254 |

| 2G/2G + 2G/1G vs 1G/1G | Total | 1.11 (1.08–1.15) | 6.14 | 0.000 | 4.51 | 0 | 0.478 | |

Abbreviations: GC, gastric cancer; MMP1, matrix metalloproteinase-1; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; vs, versus.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of the association between GC and the MMP1–1607 1G>2G polymorphisms.

Notes: (A) MMP1–1607 1G>2G allele model (2G vs 1G), among all populations in the fixed-effects model. (B) MMP1–1607 1G>2G recessive model (2G/2G vs 1G/2G + 1G/1G), among all populations in the fixed-effects model. (C) MMP1–1607 1G>2G dominant model (2G/2G + 1G/2G vs 1G/1G), among all populations in the fixed-effects model.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; MMP1, matrix metalloproteinase-1; GC, gastric cancer; vs, versus.

Heterogeneity analysis

Heterogeneity was assessed using the χ2-based Q-test among studies in the overall comparisons analysis. Heterogeneity was found in the pooling models (P<0.1 in all models); thus, the fixed-effects model was used to produce an extended pool of studies with 95% CIs. No significant heterogeneity can be seen among the six comparisons using the dominant model, recessive model, or allelic contrast.

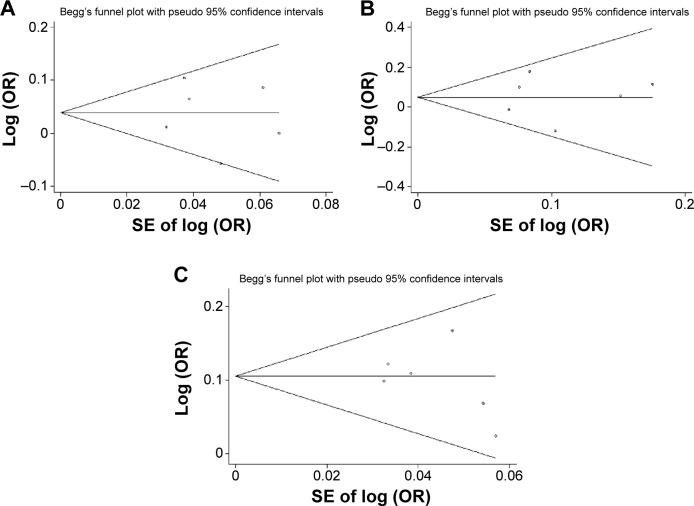

Publication bias

For MMP1−1607 1G>2G, Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test provided no evidence of publication bias in an allele model (2G vs 1G, Egger’s test: 95% CI, −4.65 to −4.81, P=0.964; Begg’s test: P=0.851). Similarly, there was no evidence of publication bias for MMP1−1607 1G>2G in a dominant model (2G/2G + 1G/2G vs Egger’s test: 95% CI, −6.78 to −3.50, P=0.425; Begg’s test: P=0.75), and in a recessive model (2G/2G vs 1G/2G + 1G/1G, Egger’s test: 95% CI, −7.48 to −6.22, P=0.81; Begg’s test: P=0.851) (Figure 3). These findings demonstrated that publication bias, if any, did not significantly affect the results of our current meta-analysis for the association between MMP1−1607 and GC risk.

Figure 3.

Begg’s funnel plot for publication bias test. Each point represents a separate study for the indicated association. Log (OR) is the natural logarithm of OR. Horizontal line is the effect size.

Notes: (A) MMP1–1607 1G>2G, 2G vs 1G; (B) MMP1–1607 1G>2G, 2G/2G vs 1G/2G + 1G/1G; (C) MMP1–1607 1G>G, 2G/2G + 1G/2G vs 1G/1G.

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; OR, odds ratio; MMP1, matrix metalloproteinase-1; vs, versus.

Discussion

MMPs can degrade the extracellular matrix and basement membrane, which is an important event in many physiological and pathological processes, including tumor invasion and metastasis. MMP expression has been found in a variety of human tumors and is significantly correlated with tumor invasion, metastasis, and therapeutic response.21 However, certain members of the MMP family exert contradicting roles at different stages during cancer progression, depending upon other factors and upon the tumor stage, tumor site, enzyme localization, and substrate profile.22

The expression level of the MMP1 gene was found to be increased in various tumors and was related to a poor prognosis in several types of cancers. MMP1 expression can be regulated by the MMP1 promoter. The polymorphism at position −1607 among the MMP1 promoters determined the increased MMP1 transcriptional level, which is attributed to its 2G allele generating a core-binding site for the E26 transformation-specific (ETS) transcription factor family, leading to the increased MMP1 expression.23

There were six articles15–20 containing six studies, including 1,377 GC cases and 1,543 non-cancer controls used in the present meta-analysis. The procedure of meta-analysis was performed by using STRATA version 12.0 software. We found that individuals with the 2G allele and 1G/2G + 2G/2G genotypes had a higher risk of GC for all models, including allele and dominant models. Interestingly, in a recessive model, there was no significant difference between 2G/2G genotype and 1G/2G + 1G/1G genotypes. These results indicated that 2G allele and heterozygote 2G might affect the individual’s phenotype more than other genotypes; the 2G allele or 1G/2G genotype carriers therefore seemed more susceptible to cancer development than 1G allele genotype carriers, or 1G/1G genotype carriers.

In the past several years, other studies have also found that the 2G allele is associated with an increased risk of other cancers. Zhang et al12 have reported that the MMP1−1607 1G>2G polymorphism is associated with an increased risk of head and neck cancer. Hu et al’s results showed that the MMP1 rs1799750 polymorphism is associated with a decreased risk of lung cancer in Asian, but not in Caucasian subjects.24 Taken together, the relationship between MMP1 rs1799750 polymorphism and cancer risk may be disease-specific and may depend on other factors, such as race, age, habits, etc. There are another two studies that relate to GC and MMP1, included in Li et al (2013)25 and Yang et al (2014).26 Meanwhile, Li’s study14,25 gathered data before August 2011, and Yang’s before June 2013. In our results, there are four more studies involved, indicating the advantages of our study compared to previously published similar studies.

Recently, multiple therapeutic agents named matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors (MMPIs) have been developed to target MMPs and to control their enzymatic activity.22 MMP1−1607 1G>2G polymorphism may be regarded as a target of MMPIs in treatment of GC in the future.

Study limitations

There are some limitations to the current study. First, we have collected all eligible studies, but the study number was not large and the numbers of patients examined were small. Second, we did not assess the potential effects of other factors such as differences in race. Third, only one SNP in MMP1 was included in this study. Some other SNPs in MMP1 also could contribute to susceptibility to GC. The effects of these SNPs and the interaction or network among these related genes should also be studied in the future.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our present meta-analysis indicates that MMP1−1607 1G>2G polymorphism is associated with GC risk. However, our results should be further validated with larger samples and in different ethnic populations, due to the limited study numbers and relatively small sample sizes.

Supplementary material

Table S1.

Scale for methodological quality assessment

| Criteria | Score |

|---|---|

| 1. Representativeness of cases | |

| Gastric cancer diagnosed according to acknowledged criteria | 2 |

| Mentioned the diagnosed criteria but not specifically described | 1 |

| Not mentioned | 0 |

| 2. Source of controls | |

| Population or community-based | 3 |

| Hospital-based GC-free controls | 2 |

| Healthy volunteers without total description | 1 |

| GC-free controls with related diseases | 0.5 |

| Not described | 0 |

| 3. Sample size | |

| >300 | 2 |

| 200–300 | 1 |

| >200 | 0 |

| 4. Quality control of genotyping methods | |

| Repetition of partial/total tested samples with a different method | 2 |

| Repetition of partial/total tested samples with the same method | 1 |

| Not described | 0 |

| 5. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) | |

| Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in control subjects | 1 |

| Hardy–Weinberg disequilibrium in control subjects | 0 |

Abbreviation: GC, gastric cancer.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Bou Kheir T, Futoma-Kazmierczak E, Jacobsen A, et al. miR-449 inhibits cell proliferation and is down-regulated in gastric cancer. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reeves GK, Pirie K, Green J, Bull D, Beral V, Million Women Study Collaborators Comparison of the effects of genetic and environmental risk factors on in situ and invasive ductal breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:930–937. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang XQ, Terry PD, Yan H. Review of salt consumption and stomach cancer risk: epidemiological and biological evidence. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2204–2213. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hua HB, Yan TT, Sun QM. miRNA polymorphisms and risk of gastric cancer in Asian population. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5700–5707. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i19.5700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du X, Wang S, Lu J, et al. Correlation between MMP1-PAR1 axis and clinical outcome of primary gallbladder carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:1086–1093. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyr108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chimal-Ramírez GK, Espinoza-Sánchez NA, Utrera-Barillas D, et al. MMP1, MMP9, and COX2 expressions in promonocytes are induced by breast cancer cells and correlate with collagen degradation, transformation-like morphological changes in MCF-10A acini, and tumor aggressiveness. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:279505. doi: 10.1155/2013/279505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Decock J, Hendrickx W, Vanleeuw U, et al. Plasma MMP1 and MMP8 expression in breast cancer: protective role of MMP8 against lymph node metastasis. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decock J, Paridaens R, Ye S. Genetic polymorphisms of matrix metal-loproteinases in lung, breast and colorectal cancer. Clin Genet. 2008;73:197–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu X, Wang Q, Hu G, et al. ADAMTS1 and MMP1 proteolytically engage EGF-like ligands in an osteolytic signaling cascade for bone metastasis. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1882–1894. doi: 10.1101/gad.1824809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutter JL, Mitchell TI, Butticè G, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the matrix metalloproteinase-1 promoter creates an Ets binding site and augments transcription. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5321–5325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang C, Song X, Zhu M, et al. Association between MMP1-1607 1G>2G polymorphism and head and neck cancer risk: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fakhoury H, Noureddine S, Chmaisse HN, Tamim H, Makki RF. MMP1-1607(1G>2G) polymorphism and the risk of lung cancer in Lebanon. Ann Thorac Med. 2012;7:130–132. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.98844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li C, Fu W, Zhang Y, et al. Meta-analysis of microRNA-146a rs2910164 G>C polymorphism association with autoimmune diseases susceptibility, an update based on 24 studies. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dedong H, Bin Z, Peisheng S, Hongwei X, Qinghui Y. The contribution of the genetic variations of the matrix metalloproteinase-1 gene to the genetic susceptibility of gastric cancer. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2014;18:675–682. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2014.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devulapalli K, Bhayal AC, Porike SK, et al. Role of interstitial colla-genase gene promoter polymorphism in the etiology of gastric cancer. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:309–314. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.141693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dey S, Ghosh N, Saha D, Kesh K, Gupta A, Swarnakar S. Matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) Promoter polymorphisms are well linked with lower stomach tumor formation in eastern Indian population. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang WL, Liang WB, Gao LB, Zhou B, Xiao FL, Zhang L. Genetic polymorphisms in Matrix Metalloproteinases-1 and -7 and susceptibility to gastric cancer: an association study and meta-analysis. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;12:203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin X, Kuang G, Wei LZ, et al. No association of the matrix metalloproteinase 1 promoter polymorphism with susceptibility to esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and gastric cardiac adenocarci-noma in northern China. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2385–2389. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i16.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumura S, Oue N, Kitadai Y, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the MMP-1 promoter is correlated with histological differentiation of gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:259–265. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0543-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luukkaa H, Klemi P, Hirsimäki P, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-7 in salivary gland cancer. Acta Oncol. 2010;49:85–90. doi: 10.3109/02841860903287197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gialeli C, Theocharis AD, Karamanos NK. Roles of matrix metallo-proteinases in cancer progression and their pharmacological targeting. FEBS J. 2011;278:16–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart K, Landvik NE, Lind H, Skaug V, Haugen A, Zienolddiny S. A combination of functional polymorphisms in the CASP8, MMP1, IL10 and SEPS1 genes affects risk of non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2011;71:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu J, Pan J, Luo ZG. MMP1 rs1799750 single nucleotide polymorphism and lung cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:5981–5984. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.12.5981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Qu L, Zhong Y, Zhao Y, Chen H, Daru L. Association between promoters polymorphisms of matrix metalloproteinases and risk of digestive cancers: a meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:1433–1447. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1446-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang TF, Guo L, Wang Q. Meta-analysis of associations between four polymorphisms in the matrix metalloproteinases gene and gastric cancer risk. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:1263–1267. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.3.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Scale for methodological quality assessment

| Criteria | Score |

|---|---|

| 1. Representativeness of cases | |

| Gastric cancer diagnosed according to acknowledged criteria | 2 |

| Mentioned the diagnosed criteria but not specifically described | 1 |

| Not mentioned | 0 |

| 2. Source of controls | |

| Population or community-based | 3 |

| Hospital-based GC-free controls | 2 |

| Healthy volunteers without total description | 1 |

| GC-free controls with related diseases | 0.5 |

| Not described | 0 |

| 3. Sample size | |

| >300 | 2 |

| 200–300 | 1 |

| >200 | 0 |

| 4. Quality control of genotyping methods | |

| Repetition of partial/total tested samples with a different method | 2 |

| Repetition of partial/total tested samples with the same method | 1 |

| Not described | 0 |

| 5. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) | |

| Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in control subjects | 1 |

| Hardy–Weinberg disequilibrium in control subjects | 0 |

Abbreviation: GC, gastric cancer.