Abstract

Backgrounds/Aims

To evaluate the effect of early enteral nutrition after hepatectomy in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients on postoperative gastrointestinal motility recovery and admission days, liver function and nutrition recovery, and postoperative complication.

Methods

From August 2010 to July 2011, 102 patients with primary HCC underwent hepatectomy. Forty two patients took a sip of water (SOW) at postoperative day (POD)#1, soft blended diet (SBD) at POD#2 (early diet group, ED group), otherwise 60 patients took a SOW at POD#3, SBD at POD#4 (conventional diet group, CD group). Postoperative flatus-pass day, stool-pass day, nausea, vomiting, admission days, immediate postoperative (POD#0) and POD#1, 3, 5, 7 profiles of albumin, prothrombin time (PT) INR, total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), white blood cell (WBC), and POD#1, 3, 5, 7 profiles of C-reactive protein (CRP), and postoperative complications cases were compared between ED group and CD group. All clinical data were compared retrospectively.

Results

Flatus-pass days (p<0.01), stool-pass days (p<0.01) and postoperative admission days (p=0.012) were shorter in ED group. Total bilirubin levels were higher at POD#0, 1, 3 but lower or similar at POD#5, 7 in ED group. AST, ALT levels were higher at POD#0 but lower at POD#1, 3, 5. There were no significant differences in albumin, PT INR, WBC, CRP and postoperative complication rates.

Conclusions

ED group had no difference in nutritional recovery and postoperative complication rates compared to CD group but it has better gastrointestinal motility recovery, liver function recovery, and shorter postoperative admission days.

Keywords: Early recovery after surgery, Early diet, Gastrointestinal motility, Liver function, Postoperative admission days

INTRODUCTION

Liver plays a pivotal role in the metabolism of the body. For this reason, many changes may be associated in the metabolism of the body after partial hepatectomy. Tubal feeding after hepatectomy has been reported to be affecting the DNA synthesis necessary in liver cell renewal through animal tests until the 1990's.1,2,3,4 Since adequate nutritional supply is crucial for the recovery of patients, sufficient postoperative parenteral nutrition is known to reduce the morbidity of patients postoperatively.5 The significance of enteral nutrition has drawn attention as tubal feeding has been verified to be more effective in liver cell regeneration, nutritional recovery, and the maintenance of normal intestinal mucosa in animal tests.6 A comparative study on 67 patients who underwent hepatectomy reported that sepsis decreased in 19 patients who received enteral nutrition compare to 48 patients who received parenteral nutrition within four postoperative days.7 These positive effects of early enteral nutrition have also been beneficial in the maintenance of normal intestinal mucosa in case of liver transplantation.8,9

Implementing early enteral nutrition within the first 24 hours postoperatively is proven to decrease postoperative complications, admission days, and death rate compare to initiating it after the first 24 hours postoperatively.10 Although, enteral nutrition is widely known to be desirable in patient recovery in case of hepatectomy, the efficacy of early enteral nutrition has not yet been completely clarified. Since most hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients are associated with liver cirrhosis, postoperative recovery may be different from the hepatectomy and recovery of patients with normal liver. Thus, the authors aimed to identify the effects of early enteral nutrition and adequate period for implementing enteral nutrition by comparing hepatocellular carcinoma patient groups that initiated diet on the first postoperative day and on the third postoperative day.

METHODS

Patients

A total of 207 HCC patients underwent hepatectomy from August 2010 to July 2011. Among those, the study excluded 22 patients who had a history of abdominal surgery or concurrently received or other surgeries besides hepatectomy. In addition, other 83 patients were excluded since diet plans were not implemented. As a result, a total of 102 were included to study population. Among those, 42 patients took a sip of water (SOW) at postoperative day (POD)#1, soft blended diet (SBD) at POD#2 (early diet group, ED group), otherwise 60 patients took a SOW at POD#3, SBD at POD#4 (conventional diet group, CD group). Patients underwent postoperative routine 5% glucose administration in empty stomach. A 5% glucose solution had been reduced after initiating SBD. The presence of liver cirrhosis was identified through histological examination postoperatively. The extents of hepatectomy were categorized into less than one segmentectomy (wedge resection and segmentectomy) and more than one sectionectomy (sectionectomy, central bisectionectomy, right/left hemi-hepatectomy, and trisectionectomy).

Evaluation process

To evaluate the effect of early enteral nutrition after hepatectomy in HCC patients on postoperative gastrointestinal motility recovery and admission days, liver function and nutrition recovery, and postoperative complication were compared. The indicators of gastrointestinal motility recovery were postoperative flatus-pass day, stool-pass day, nausea, vomiting, and the presence of paralytic ileus. The study examined immediate postoperative (POD#0) and POD#1, 3, 5, 7 profiles of albumin, prothrombin time (PT) INR, total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) as the indicators of liver function & nutrition recovery. Furthermore, the study identified fever, immediate postoperative (POD#0) and POD#1, 3, 5, 7 profiles of white blood cell (WBC) and C-reactive protein (CRP), and postoperative complications as the indicators of postoperative infection.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using the software SPSS version 18.0. T-test was conducted to examine continuous variables after ANOVA and chi-square test was carried out to analyze nominal variables. Differences at p-value of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

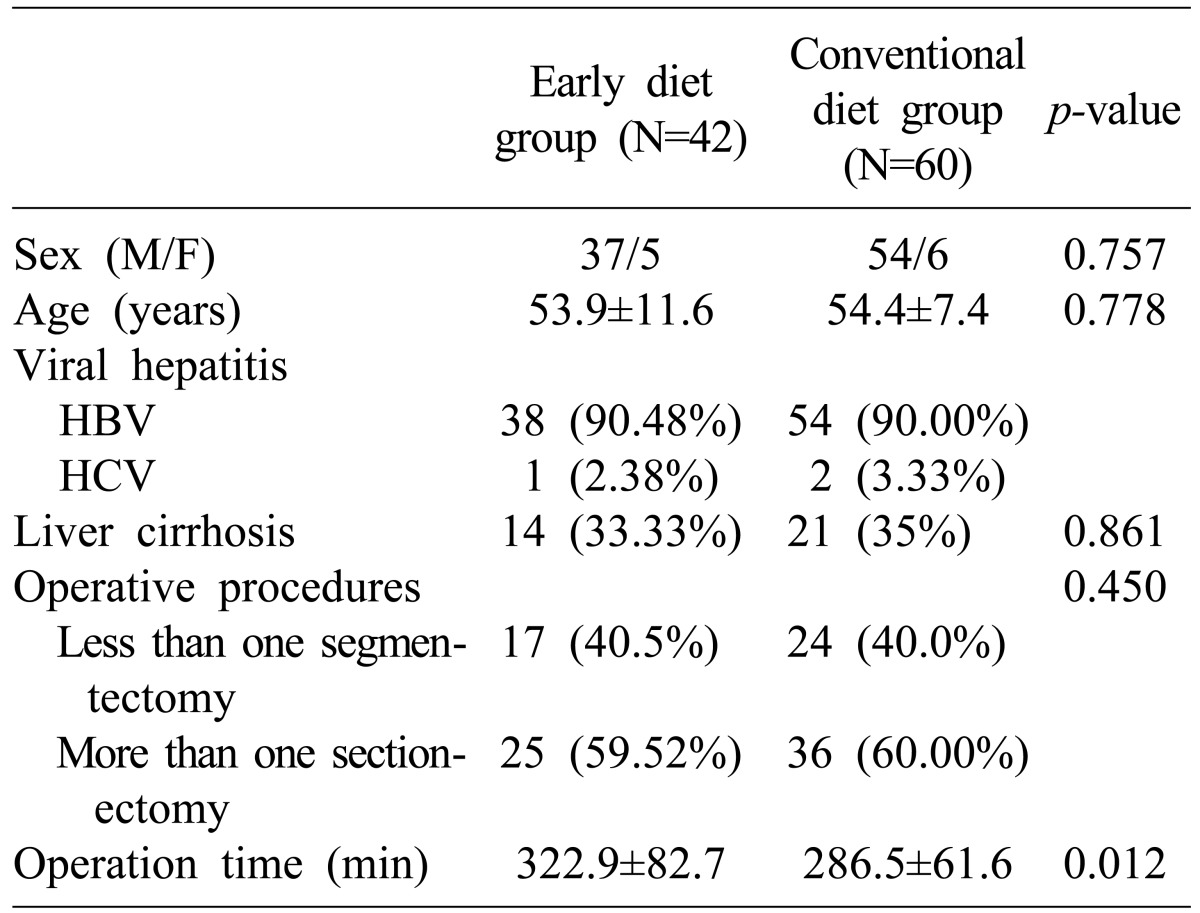

The clinical characteristics of two groups were described in Table 1. There were no differences in sex, age, causal diseases, liver cirrhosis, and the scope of operative procedures. However, operation time was verified to be significantly longer in ED group with the mean value of 322.9 minutes compare with 286.5 minutes (p=0.012).

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus

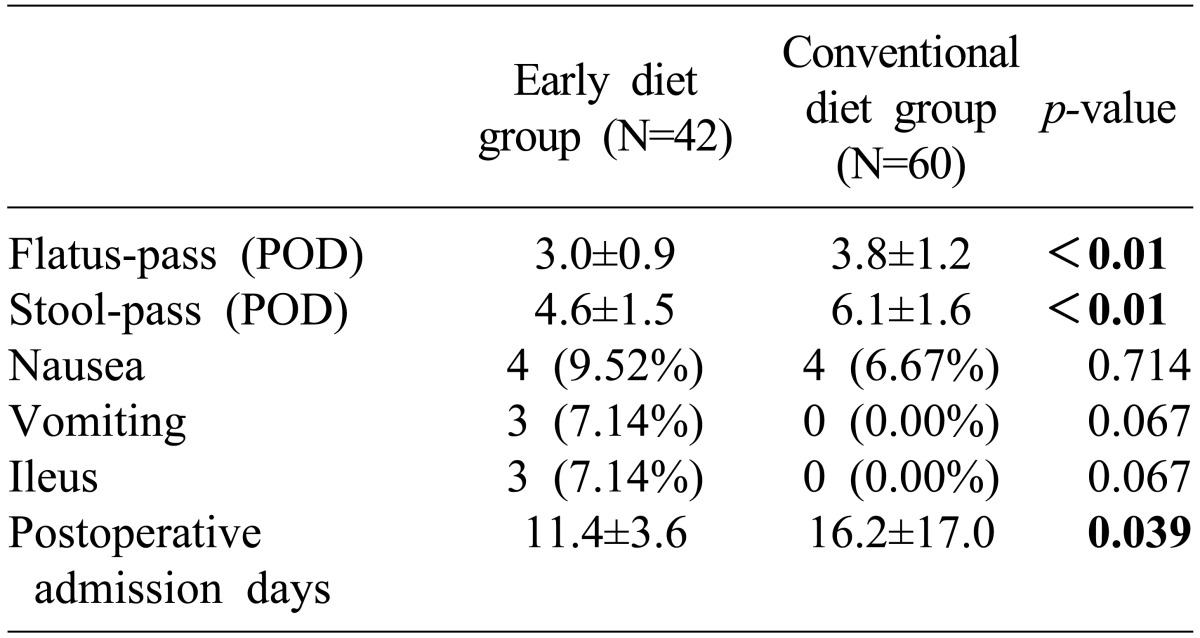

In addition, ED group exhibited significant decreases in gastrointestinal motility recovery and postoperative admission days with flatus-pass day (3.02 days vs. 3.77 days, p≤0.01), stool-pass day (4.63 days vs. 6.14 days, p≤0.01), and postoperative admission days (11.40 days vs. 16.17 days, p=0.039). However, no significant differences were shown in the incidence of nausea, vomiting, and ileus (Table 2).

Table 2. Gastrointestinal motility recovery and postoperative admission days.

POD, postoperative days

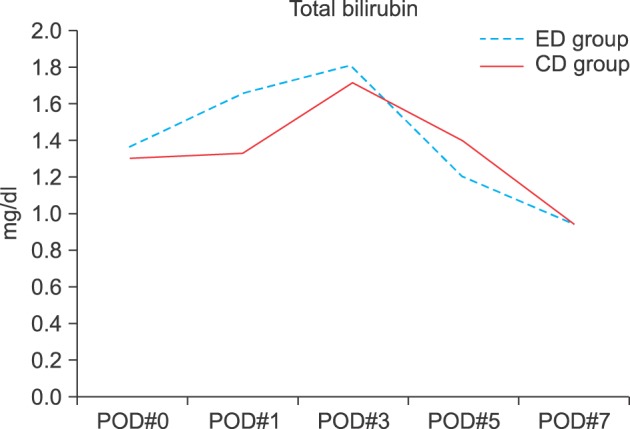

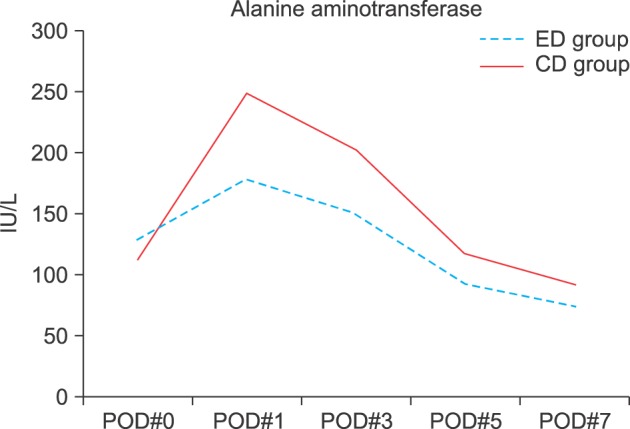

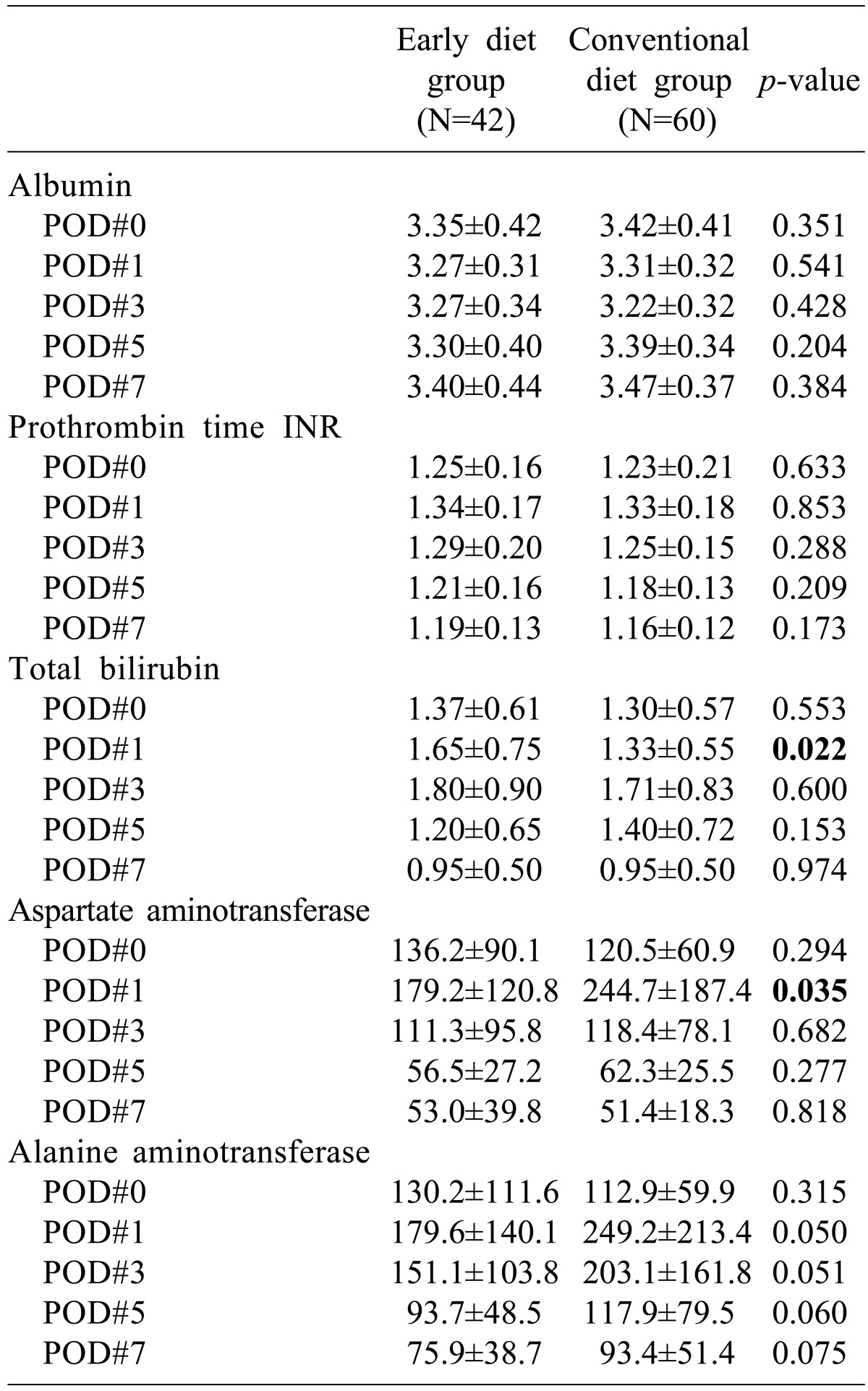

No significant differences were observed between groups in albumin and PT INR values in terms of liver function and nutrition recovery. However, total bilirubin level became the same or lower from the fifth postoperative day after being high from immediate postoperative to the third postoperative day in ED group (Fig. 1). Although AST and ALT values were high immediate postoperatively, they decreased on POD#1, 3, and 5 (Fig. 2) (Table 3).

Fig. 1. Comparison of total bilirubin level between early diet (ED) group and conventional diet (CD) group. POD, postoperative days.

Fig. 2. Comparison of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level between early diet (ED) group and conventional diet (CD) group. POD, postoperative days.

Table 3. Liver function and nutrition recovery.

POD, postoperative days

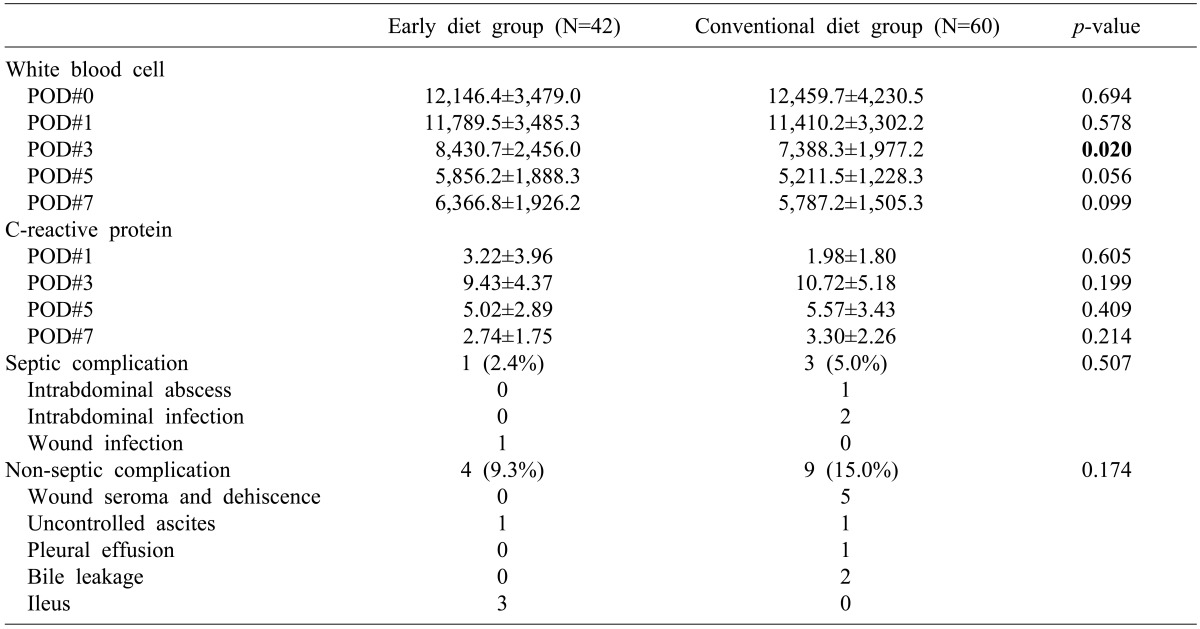

Fever was more frequently observed in ED group as the postoperative complication and no differences were detected in WBC and CRP values within the normal range. Although other complications were more commonly occurred in CD group, there was no statistical significance (Table 4).

Table 4. Postoperative complication.

POD, postoperative days

DISCUSSION

The side effects of nausea, vomiting, and ileus were more frequently detected in ED group, exhibiting some shortcomings compared to patients with conventional diet. However, gastrointestinal motility in patients with early enteral nutrition recovered better in the early stage as proven by flatus-pass and stool-pass. As a result, the admission days of patients were shortened by five days in average. Nausea, vomiting, and ileus are mainly affected by narcotic analgesics used postoperatively. Our institution uses parenteral narcotic analgesics in all patients instead of epidural anesthesia due to the risk of bleeding induced by liver cirrhosis in HCC patients undergoing hepatectomy. More effective outcomes are forecasted to be acquired if further studies are performed on reducing the use narcotic analgesics as with the use of local patient controlled anesthesia. Another effect of early enteral nutrition is a noticeable decrease in total bilirubin. Diet implementation is well known to facilitate the elimination of bile and the study results have aligned with such mechanism. Although AST and ALT values in ED group were higher immediate postoperatively compare to the control group, these levels decreased at POD# 1, 3, and 5. Further studies need to take into consideration the fact that early enteral nutrition not only promotes the regeneration of liver cells but also influences liver cell protection.6 Since albumin has a longer half-life and its synthesis takes a long time, no significant difference until the first postoperative week is thought to be attributable to such causes. Prealbumin with a shorter half-life is thought to be a better marker in future studies.5 The incidence of septic complications was lesser (2.4% vs. 5.0%), but no statistical significance was attributable to a small number of study population with the low incidence of complications. More frequent early postoperative fever may be interpreted to be resulted from longer operation time in ED group as shown in the clinical characteristics of patients. No difference in WBC and CRP values, well reflecting the presence of infections, is thought to be resulted from commonly detected postoperative non-infectious diseases such as atelectasis. Although infectious complications were more frequently detected, the findings were hard to conclude since intra-abdominal infections are profoundly related with surgical outcomes besides from infections in the abdominal wounds. However, both infectious complications and non-infectious complications were frequently observed in the control group. Therefore, the relationship between the complications and diet implementation are thought to be verified by analyzing a study with a large number of subjects.

There were some limitations since the study was a retrospective analysis and study subjects were not randomly assigned in two groups. However the study was meaningful to verify diet implementation after hepatectomy especially in patients associated with liver cirrhosis.

As summary, early enteral nutrition implemented on the first postoperative day was verified to be beneficial in shortening the recovery period of intestine and liver functions in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma compare with the third postoperative day diet. The better results are anticipated when methods to overcome nausea and vomiting such as improved pain management and therefore early postoperative diet can be done as routine postoperative recovery even in the setting of liver cirrhosis.

References

- 1.Barbiroli B, Potter VR. DNA synthesis and interaction between controlled feeding schedules and partial hepatectomy in rats. Science. 1971;172:738–741. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3984.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirsch RE, Saunders SJ, Frith LO, et al. The effect of intragastric feeding with amino acids on liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in the rat. Am J Clin Nutr. 1979;32:738–740. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/32.4.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kallenbach M, Roome NO, Schulte-Hermann R. Kinetics of DNA synthesis in feeding-dependent and independent hepatocyte populations of rats after partial hepatectomy. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1983;16:321–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torosian MH. Perioperative nutrition support for patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery: critical analysis and recommendations. World J Surg. 1999;23:565–569. doi: 10.1007/pl00012348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan ST, Lo CM, Lai EC, et al. Perioperative nutritional support in patients undergoing hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1547–1552. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412083312303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aoi T. Influence of enteral nutrition on hepatic regeneration and small intestinal epithelium after hepatectomy in rat-comparative assessment with TPN. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1995;96:295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mochizuki H, Togo S, Tanaka K, et al. Early enteral nutrition after hepatectomy to prevent postoperative infection. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:1407–1410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y, Chen Y, Zhang J, et al. Protective effect of glutamine-enriched early enteral nutrition on intestinal mucosal barrier injury after liver transplantation in rats. Am J Surg. 2010;199:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikegami T, Shirabe K, Yoshiya S, et al. Bacterial sepsis after living donor liver transplantation: the impact of early enteral nutrition. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis SJ, Andersen HK, Thomas S. Early enteral nutrition within 24 h of intestinal surgery versus later commencement of feeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:569–575. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0592-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]