Abstract

Objective

Cancer patients report high rates of distress. The related constructs of meaning in life (MiL) and sense of coherence (SOC) have long been recognized as important factors in the psychological adjustment to cancer; however, both constructs’ associations with distress have not been quantitatively reviewed or compared in this population. Informed by Park’s integrated meaning-making model and Antonovsky’s salutogenic model, the goals of this meta-analysis were the following: (1) to compare the strength of MiL-distress and SOC-distress associations in cancer patients; and (2) to examine potential moderators of both associations (i.e., age, gender, ethnicity, religious affiliation, disease stage, and time since diagnosis).

Methods

A literature search was conducted using electronic databases. Overall, 62 records met inclusion criteria. The average MiL-distress and SOC-distress associations were quantified as Pearson’s r correlation coefficients and compared using a one-way ANOVA.

Results

Both MiL and SOC demonstrated significant, negative associations with distress (r = 0.41, 95% CI: −0.47 to −0.35, k = 44; and r = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.67 to −0.51, k = 18, respectively). Moreover, the MiL-distress association was significantly smaller than the SOC-distress association (Qb = 10.42, df = 1, p < 0.01). Neither association varied by the tested moderators.

Conclusions

Findings provide support for the clinical relevance of MiL and SOC across demographic and medical subgroups of cancer patients. The strength of the SOC-distress association suggests that incorporating aspects of SOC (e.g., the perceived manageability of life circumstances) into meaning-centered interventions may improve their effectiveness for distressed cancer patients.

Background

Cancer patients have high rates of distress, including reduced emotional well-being and increased anxiety and depressive symptoms [1,2]. Cancer patients’ distress is associated with poor health-related outcomes (e.g., global health status, cognitive functioning, and fatigue) [3], with clinically elevated depressive symptoms predicting mortality [4,5]. The related constructs of meaning in life (MiL) and sense of coherence (SOC) are recognized as important factors in patients’ psychological adjustment to cancer [6-8]. In the succeeding texts, a conceptual overview of MiL and SOC is provided, and research on their relations to distress in cancer patients is reviewed.

Meaning in life and distress in cancer patients

Although multiple definitions of MiL have been proposed [9], MiL is generally defined as a person’s subjective feelings of meaningfulness, including a sense of purpose or direction, comprehension of life’s circumstances, and significance [10-14]. One’s sense of MiL is likely acquired through interpersonal relationships and culture [11]. Numerous theorists have described the developmental nature of MiL, suggesting that the foundation of one’s MiL begins early in childhood and is refined as one ages and experiences life [11,15]. MiL is a central component of spirituality; however, it is conceptually distinct from other components of spirituality, including feelings of peace and reliance on faith during illness [16]. MiL and other facets of spirituality may change through a process of meaning-making, defined as cognitive efforts to reduce the discrepancy between one’s appraisal of a stressor and one’s global meaning (i.e., beliefs, goals, and MiL) [7,17].

Numerous meaning-making theories exist; however, Park’s integrated meaning-making model [7] was developed as a synthesis of prominent theories. The integrated meaning-making model posits a negative relationship between MiL and distress [7]. From this perspective, if stressful life events (e.g., a cancer diagnosis) challenge a person’s MiL, meaning-making efforts are initiated. Successful meaning-making efforts result in a greater or restored sense of MiL and reduced distress.

Two narrative reviews examined MiL and other aspects of spirituality in relation to mental health outcomes in cancer patients [6,18]. Both reviews highlighted the wide range of effect sizes reported across studies, with the majority of studies reporting a negative spirituality-distress association. The authors noted that differences in effect sizes could be related to variations in sample characteristics (e.g., disease stage) and measurement of spiritual constructs. For example, many widely used measures of spirituality contain items that directly refer to emotional well-being, thus artificially inflating associations with distress. Moreover, some studies examined spirituality as a unidimensional construct, despite evidence suggesting that different components of spirituality are differentially related to distress [6].

Sense of coherence and distress in cancer patients

Similar to MiL, SOC has received significant research attention in cancer patients; however, the SOC-distress association has not been reviewed in this population. SOC is conceptualized as a global orientation to life experiences, including the degree to which life is viewed as comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful [8]. Antonovsky suggested that SOC is similar to a personality trait or coping disposition that develops early in childhood and later becomes more solidified based on the degree to which an individual has a sense of control over his or her environment and outcomes [8]. According to Antonovsky’s salutogenic model, a person’s physical and mental health is significantly determined by his or her attitude (i.e., global orientation) toward life. Specifically, Antonovsky posited that people with a high degree of SOC are more likely to use available internal and external resources to meet the demands of life and, thus, maintain well-being [8]. Some studies with cancer patients have reported a strong, negative SOC-distress association [19,20]; however, the wide range of observed effect sizes suggests possible moderating variables [21,22]. Conversely, the salutogenic model predicts a similar SOC-distress association across demographic and medical subgroups [8].

Meaning in life and SOC are related but distinct constructs. As noted by Steger [23], SOC is sometimes mistakenly equated with MiL [24]. Although they both encompass the degree to which a person feels that his or her life is meaningful and comprehensible [25,26], only SOC includes the perceived manageability of life circumstances. Thus, based on Antonovsky’s salutogenic model [8], one would predict that SOC would be more strongly related to distress than MiL, given that SOC is more similar to a coping disposition. In addition, Antonovsky [8] theorized that SOC is a stable trait, whereas Park’s integrated meaning-making model [7] suggests MiL can change over time [11,15,27]. Longitudinal studies have yielded mixed results regarding the stability of SOC, with some studies showing decreases in SOC following a traumatic event [28,29]. Similarly, MiL has been shown to change over time and often fluctuates concurrently with emotional well-being [30,31]. In sum, MiL and SOC share some commonalities; however, these constructs are theoretically distinct and have not been compared in relation to distress in cancer patients.

The present study

To address this gap in the literature, the current meta-analysis provides an initial examination of the extent to which MiL and SOC are related to distress in cancer patients. Meaning-centered interventions for distressed cancer patients have increased MiL and reduced distress [32,33]; however, no intervention trials for cancer patients, with the exception of two mindfulness-based stress reduction trials [34,35], have included SOC as an outcome variable. Results of this study will provide an evidence regarding the clinical relevance of MiL and SOC and inform psychosocial interventions for distressed cancer patients. Guided by Park’s integrated meaning-making model [7] and Antonovsky’s salutogenic model [8], the goals of this meta-analysis are the following: (1) to compare the strength of MiL-distress and SOC-distress associations in cancer patients; and (2) to examine potential moderators of both associations (i.e., age, gender, ethnicity, religious affiliation, disease stage, and time since diagnosis).

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies included in this meta-analysis met a number of inclusion criteria. These criteria included the following: (1) being written in English, (2) examining a sample of adult cancer patients across the disease trajectory (e.g., initial diagnosis, long-term survivor, and end of life), and (3) quantitatively measuring MiL and/or SOC as well as distress. Regarding MiL measures, records were potentially eligible if they included a valid self-report measure of MiL that assessed the presence of a subjective sense of life as meaningful, including a sense of purpose or direction, comprehension of life circumstances, and significance [10-14]. MiL measures were selected a priori based on recent MiL measurement review articles [26,36] (for a list of study measures, see Online Supporting Information 1). One of these measures was the Meaning subscale of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT–Sp). Initial validation of the FACIT-Sp showed that two components explained the observed variance best: Meaning/Peace and Faith [9]. The combined Meaning/Peace subscale included items that assessed both MiL and a sense of harmony and peace associated with connection to something larger than the self. Recently, however, two studies [16,37] have confirmed that a three-factor structure of the FACIT-Sp fits the data best (i.e., separation of the Meaning, Peace, and Faith subscales). Moreover, some researchers have contended that the Peace subscale is confounded with distress [6]; thus, in the current study, only the Meaning subscale was included.

As noted by Park [7], different components of the integrated meaning-making model demonstrate different associations with distress. Thus, MiL measures were excluded if they assessed meaning-related constructs (e.g., meaning-making processes and appraised meaning) without a specific MiL subscale. In addition, spirituality measures that included MiL items while referencing God or a specific religion or assessing additional constructs (e.g., humility and responsibility) were excluded from this review, as MiL is conceptually distinct from religiosity [9].

Eligible measures of SOC were restricted to versions of Antonovsky’s Orientation to Life Questionnaire [25], as they are the only validated measures of this construct. Theory and psychometric evaluations support the use of the Orientation to Life Questionnaire as a unidimensional measure [25]; that is, Antonovsky [25] and others [36] have cautioned against separating the three components (i.e., comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness). Thus, only the Orientation to Life Questionnaire total score was included in the current study.

Validated self-report measures of distress were selected a priori. Additional measures of distress were included if they had acceptable psychometric properties, including published reliability (i.e., alpha >.70) or validity evidence (e.g., strongly correlated with other reliable measures) (for a list of distress measures, see Online Supporting Information 2).

Records were excluded if MiL, SOC, or distress were only measured after an intervention; however, intervention studies were included if measures were administered at baseline. When there were multiple records for the same sample (e.g., conference abstract and a published article), peer-reviewed records were chosen over other records (e.g., dissertations and conference abstracts), and records with a larger portion of the sample were selected over records with a smaller portion of the sample.

Literature search

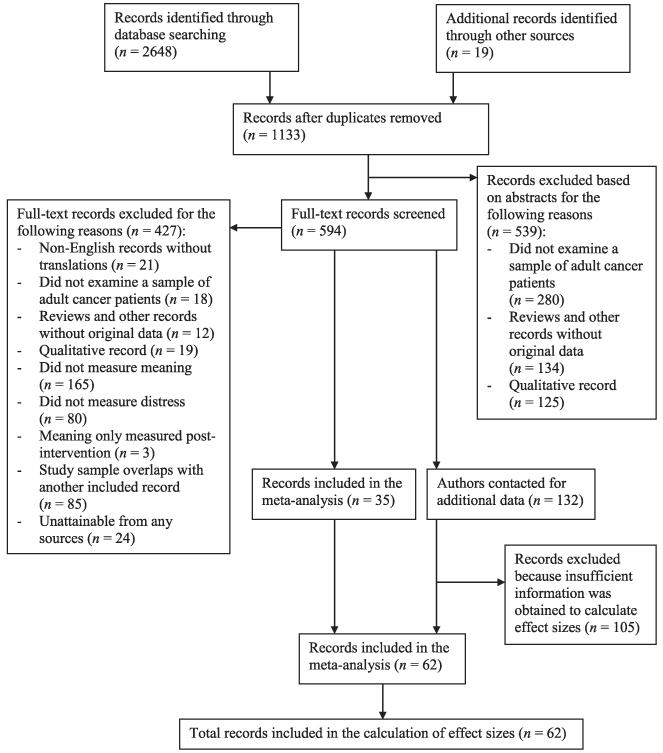

A systematic literature search was conducted to identify studies examining the MiL-distress and SOC-distress associations in cancer patients. First, we examined all of the records cited in Visser and colleagues’ [6] narrative review of spirituality and emotional well-being in cancer patients as well as Schreiber and Brockopp’s [18] narrative review of spirituality/religiosity and emotional well-being in breast cancer survivors. Second, we conducted a literature search using the following databases: Embase, MEDLINE, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, Pubmed, and Web of Science. The following Boolean search phrase was used in each of the databases: (cancer OR oncolog* OR neoplasm) and (‘spiritual well-being’ OR ‘meaning-making’ OR ‘meaning in life’ OR ‘purpose in life’ OR ‘sense of coherence’). The initial database searches were completed on February 8, 2014. Electronic mail alerts were used to identify records published after the initial search. Third, abstracts were reviewed and clearly ineligible records (e.g., qualitative and non-cancer populations) were excluded; the remaining records were examined in-depth. Fourth, after compiling all of the relevant records, references were examined to identify any records that may have been missed in the database searches. Finally, authors were contacted for any records that were lacking sufficient information for either determining eligibility or conducting analyses. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines were used to report findings of this meta-analysis [38]. For the record retrieval flowchart, see Figure 1. The flowchart and analyses included all records that were obtained prior to October 24, 2014.

Figure 1.

Record retrieval flowchart

Moderator extraction

Potential continuous moderators were coded, including age (i.e., mean age of the sample), gender (i.e., percent female), ethnicity (i.e., percent African American), religious affiliation (i.e., percent with religious affiliation), time since diagnosis (i.e., mean days since diagnosis), and disease stage (i.e., percent with advanced-stage cancer). Concerning ethnicity, few studies reported ethnic backgrounds other than Caucasian and African American; therefore, other ethnicities could not be compared. We decided to code ethnicity as percent African American because of the centrality of spirituality in African Americans’ social systems [39]. Specifically, it has been theorized that the MiL-distress association may be particularly strong for African Americans relative to Caucasians and other ethnic groups [40,41]. Concerning disease stage, we used the National Cancer Institute [42] classifications for advanced-stage cancer, including the following: (1) stage III, IV, and metastatic breast cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, gynecological cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and Hodgkin lymphoma; (2) stage III and metastatic testicular cancer; and (3) extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. Publication status (i.e., published = 1 and unpublished = 0) was coded as a potential dichotomous moderator.

The first author coded all of the aforementioned variables, and the second author coded a random sample of 25% of the records. The overall percent agreement between the coders was 97.4%. All disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Meta-analytic method

The current meta-analysis examined the strength of MiL-distress and SOC-distress associations in cancer patients. When a record provided multiple effect sizes for these associations (e.g., MiL-anxiety symptoms and MiL-depressive symptoms), the following decisions were made based on guidelines for complex data structures [43,44]. First, when multiple measures of MiL were used within one record, they were averaged, as different measures of MiL are often highly correlated [26]. Second, different measures of distress within one record were averaged. The high correlation among distress measures provides evidence for a common underlying construct [45-47]; furthermore, many studies with cancer patients have combined various distress measures for analyses [47,48]. In both averaging scenarios, the averages were weighted by sample size. Thus, each record contributed only one effect size for each association to ensure statistical independence and reduce bias [43,44]. Additionally, only univariate associations were included in the analyses; thus, authors were contacted, and univariate associations were requested for records that reported multivariate relationships. Lastly, only cross-sectional effect sizes were included in the analyses because potential moderators were measured at baseline (e.g., time since diagnosis would increase from baseline to follow-up).

All data were coded in SPSS (version 20.0; Chicago, IL, USA). Before running analyses, a stem and leaf plot was used to characterize the distribution of effect sizes as well as identify outliers. Then the effect size contributed from each record was weighted by the sample size and transformed using a Fisher’s Z-transformation [49]. Next, Wilson’s [50] SPSS macro ‘MeanES’ was used to calculate the mean effect size. A random-effects model was chosen over a fixed-effects model because a random-effects model computes less biased and more conservative effect size estimates [43,44,49]. Wilson’s [50] ‘MeanES’ macro also converts the aggregated mean Fisher’s Z-score back to r in order to improve the interpretability of the effect size. Heterogeneity of the effect sizes was examined using the Q-statistic provided by Wilson’s [50] macro and subsequent calculation of the I2-statistic. An I2 of at least 25% is commonly used to indicate that between-study variability is greater than expected by chance and, thus, moderators should be considered [43]. Following, Orwin’s fail-safe N was calculated to estimate the number of records with null effects (r = .00) that would be required to reduce the mean effect size to a non-significant level [49,51]. The mean effect sizes for the MiL-distress and SOC-distress associations were then compared using Wilson’s [50] ‘MetaF’ macro, which performs a one-way ANOVA. Moderation analyses were subsequently conducted using Wilson’s [50] ‘MetaReg’ macro for continuous moderators, which performs a weighted generalized least square regression. Lastly, Wilson’s [52] ‘MetaF’ macro was used for the dichotomous moderator (i.e., publication status). For all moderation analyses, mixed-effects models were used, and each moderator was examined independently in order to maximize the number of included records.

Results

Sample

A total of 167 records were identified that measured MiL or SOC and distress in adult cancer patients (see Figure 1 for record retrieval flowchart). Thirty-five records included enough information for effect size calculations and 132 records did not include sufficient information. Thus, we contacted the authors of these 132 records and obtained sufficient data for 27 of them. The remaining 105 records were excluded from all analyses (Online Supporting Information 3 and 4). Of the 105 excluded records, the majority (n = 77) used the FACIT-Sp to measure MiL, and 18 studies measured SOC. Overall, 98 associations were provided from 62 records, including 53 journal articles, eight doctoral dissertations, and one conference abstract. As noted previously, effect sizes were averaged when a record reported more than 1 value for the association; thus, the final database consisted of 62 associations. The MiL-distress analyses included 44 associations, and the SOC-distress analyses included 18 associations.

The median sample sizes of the included records were 154.00 (SD = 1314.10; range = 19.00–8805.00; k = 44) and 85.50 (SD = 94.43; range = 20.00–342.67; k = 18) for MiL-distress and SOC-distress records, respectively. The mean ages of the samples were 56.08 (SD = 6.48; range = 43.70–70.00; k = 41; MiL-distress records) and 59.90 (SD = 10.32; range = 37.00–69.90; k = 12; SOC-distress records). Calculating gender continuously, the mean percentages of women across records were 66.56% (SD = 23.02%; k = 42; MiL-distress records) and 57.99% (SD = 32.65%; k = 17; SOC-distress records). Calculating ethnicity continuously, the mean percentages of African Americans across records were 22.44% (SD = 33.12%; k = 15; MiL-distress records) and 28.76% (SD = 47.80%; k = 4; SOC-distress records). On average across MiL-distress records, 84.24% (SD = 13.31; k = 14) reported a religious affiliation; none of the SOC-distress records reported religious affiliation. Concerning medical variables, the mean percentages with advanced-stage cancer (e.g., stage III, IV, or metastatic) were 56.62% (SD = 33.41%; k = 23) and 34.15% (SD = 30.01%; k = 10), and the mean days since diagnosis were 1488.40 (SD = 833.75; k = 17) and 1435.48 (SD = 2239.39; k = 4) for MiL-distress and SOC-distress records, respectively. See Online Supporting Information 5 for additional information about the included records.

Effect sizes

Before running analyses, a stem and leaf plot was used to display the distribution of effect sizes and identify possible outliers (Online Supporting Information 6). For the MiL-distress association, three outliers were identified [53-55]. However, there were no significant differences in any of the results when these records were included or excluded; thus, they were included in the final analyses [44]. No outliers were identified for the SOC-distress association.

Mean effect sizes were computed for the MiL-distress and SOC-distress associations. Using a random-effects model, the mean effect size for the MiL-distress association was moderate, r = −.41 (SE = .03; range: −.67 to .08; k = 44; N = 18,280.17), and significantly different from zero (z = −13.78; p <0.0001), with a 95% CI of −.47 to −.35. The mean effect size for the SOC-distress association was large, r = −.59 (SE = .04; range: −.69 to −.37; k = 18; N = 2252.67), and significantly different from zero (z = −14.82; p <0.0001), with a 95% CI of − .67 to −.51. The average effect size for the MiL-distress association was significantly smaller than the average effect size for the SOC-distress association (Qb = 10.42, df = 1, p = .001, k = 62).

Orwin’s fail-safe N was calculated and showed that 69.64 missing records with null effects (r = .00) would be needed to reduce the overall MiL-distress association below a significant level (r = .16, p > .05) for a sample of 154.00 participants (the median sample size for the MiL-distress association). For the SOC-distress association, 31.87 missing records with null effects would be needed to reduce the overall effect below a significant level (r = .21, p > .05) for a sample of 85.5 participants (the median sample size for the SOC-distress association).

Concerning heterogeneity, the I2 index indicated that 90.43% (Q = 449.53) of the variability in the MiL-distress association and 66.12% (Q = 50.18) of the variability in the SOC-distress association were due to between-study variability rather than sampling error. Therefore, moderation analyses were conducted to examine study-level factors that might explain some of the between-study variance in both associations.

Moderator variables

Continuous moderator variables were age, gender (i.e., percent female), ethnicity (i.e., percent African American), religious affiliation (i.e., percent with a religious affiliation), disease stage (i.e., percent with advanced-stage cancer), and days since diagnosis. The MiL-distress association was not significantly moderated by age (b = .0019, SE = .0049, z = .39, 95% CI = −.0078 to .0116, k = 41), gender (b = −.0005, SE = .0014, z = −.34, 95% CI = −.0033 to .0022, k = 42), ethnicity (b = .0006, SE = .0019, z = .31, 95% CI = −.0031 to .0042, k = 15), religious affiliation (b = −.0003, SE = .0030, z = −.11, 95% CI = −.0063 to .0056, k = 14), disease stage (b = −.0013, SE = .0011, z = −1.23, 95% CI = .0034 to .0008, k = 23), or days since diagnosis (b = −.0001, SE = .0001, z = −.73, 95% CI = −.0002 to .0001, k = 17). Similarly, the SOC-distress association was not significantly moderated by age (b = −.0085, SE = .0049, z = −1.73, 95% CI = −.0182 to .0012, k = 12), gender (b = .0009, SE = .0012, z = .76, 95% CI = −.0014 to .0033, k = 17), ethnicity (b = .0007, SE = .0013, z = .57, 95% CI = −.0018 to .0033, k = 4), disease stage (b = .0004, SE =−.0017, z = .24, 95% CI = −.0029 to .0037, k = 10), or days since diagnosis (b = .0000, SE = .0000, z = −.73, 95% CI = −.0001 to .0001, k = 4). Of note, religious affiliation could not be run as a potential moderator of the SOC-distress association because no records reported this variable. Lastly, publication status was not a significant moderator of either the MiL-distress association (Qb = .08, df = 1, p = .78, k = 44) or the SOC-distress association (Qb = 2.30, df = 1, p = .13, k = 18).

Conclusions

In the current meta-analysis, both MiL and SOC demonstrated significant negative associations with distress in cancer patients. Moreover, there was a significant difference between the two associations: the MiL-distress association was moderate, whereas the SOC-distress association was large. Consistent with Park’s integrated meaning-making model [7] and Antonovsky’s salutogenic model [8], these findings suggest that MiL and SOC are related but distinct constructs that play important roles in patients’ psychological adjustment to cancer. Moreover, the results support targeting these constructs, especially SOC, in interventions for distressed cancer patients.

Park’s integrated meaning-making model [7] suggests multiple interpretations of the moderate negative association between MiL and distress in cancer patients. First, for some patients, higher levels of MiL and lower levels of distress may reflect successful meaning-making efforts (i.e., ‘meanings made’) and, thus, less distress. Indeed, a longitudinal study with survivors of various cancers found that meaning-making efforts were related to less distress through meanings made [31]. Second, the MiL-distress association may reflect a non-distressing appraisal of cancer in a subgroup of patients [7,56]. One hypothesis is that some cancer patients have a global meaning framework that more readily assimilates or accommodates stressful life events [57-59]. For example, a qualitative study with advanced cancer patients found that some responded to their poor prognosis with a peaceful resolve (e.g., ‘My life is in God’s hands’) [56]. Third, lower levels of MiL and higher levels of distress may indicate a shattering of a person’s global meaning and unsuccessful meaning-making attempts [60]. If meaning-making efforts do not reduce the discrepancy between a person’s appraisal of cancer and his or her global meaning, distress may continue and even increase over time [7].

Numerous potential moderators of the MiL-distress association were examined, including age, gender, ethnicity, religious affiliation, disease stage, and time since diagnosis. The strength of the MiL-distress association remained statistically the same across all tested variables, suggesting that MiL-distress association does not vary across subgroups. If future studies continue to support these findings, meaning-centered interventions may be equally important across a variety of demographic and medical subgroups. However, alternative explanations for these findings exist. For example, statistical power for detecting effects was likely reduced because of a restriction of range in some of the tested moderators. For example, the mean sample age did not include younger adults (range = 44–70 years) and, when reported, the mean percent of the sample with a religious affiliation was high (range = 58–100%). Thus, more primary studies with diverse populations are needed before definitive conclusions can be made regarding moderators of the MiL-distress association.

The current results are also consistent with Antonovsky’s salutogenic model [8]. According to Antonovsky’s model, a large negative SOC-distress association suggests that cancer patients who view life as comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful (i.e., high levels of SOC) experience less distress. Patients with high levels of SOC may rely on their available resources and, thus, maintain their well-being in the midst of stressful life events. For example, these patients may be more likely to approach difficult situations in a flexible way, such as matching coping strategies to the presenting problem [8]. Similar to the MiL-distress association, all tested moderators of the SOC-distress association (i.e., age, gender, ethnicity, disease stage, and time since diagnosis) were non-significant. These results are congruent with Antonovsky’s salutogenic model [8], which posits consistency of the SOC-distress association across many demographic and medical subgroups. However, alternative explanations for these null results warrant consideration. For example, some of the moderator analyses (i.e., ethnicity and time since diagnosis) included a limited number of studies, and meta-analyses with fewer than six publications have less than 80% power to detect small effects [43,49]. Moreover, religious affiliation could not be run as a moderator, as no studies reported this variable. In sum, more primary studies are needed before definitive conclusions regarding moderators of the SOC-distress association can be made.

The present study is limited by the same factors that limit the studies included in the analyses [44]. The majority of included studies had samples of primarily middle-aged and older adult Caucasians, and, when religious affiliation was reported, most participants identified themselves as religious. Further studies are needed with more diverse populations. In addition, all studies were cross-sectional and analyses were correlational. Thus, the directions of the MiL-distress and SOC-distress associations cannot be confirmed. To date, only a few studies have longitudinally examined these associations, and the results have been mixed [24,30,31]. Given the lack of prospective research in this area, the extent to which a cancer diagnosis may shatter one’s global meaning is unclear. A few studies have examined this question retrospectively (i.e., asked patients to think about the time of initial diagnosis) [61]. Ideally, future studies should assess MiL before and after a cancer diagnosis. Measurement issues also warrant attention in future research. Concerning distress measures, our examined studies only used self-report instruments. Future studies should consider incorporating clinician-assessed distress given that certain distress measures may be confounded with cancer or treatment-related symptoms [62]. Moreover, cancer stage and time since diagnosis were based on self-report in the majority of studies. The poor reliability of self-reported medical variables among cancer patients has been well documented [63-65]. Future studies should consider collecting disease-related variables from medical records. Lastly, the current study was susceptible to publication bias favoring statistically significant results (i.e., the file drawer problem); however, numerous unpublished studies were included, and publication status was not a significant moderator. In addition, Orwin’s fail-safe N analyses indicated that a large number of null studies would be needed to reduce the overall effects below meaningful levels.

The current findings have numerous implications for clinical practice. To begin, the moderate MiL-distress and large SOC-distress associations provide evidence for the importance of these constructs for cancer patients’ mental health. A recent meta-analysis examined the effects of various existential therapies on psychological outcomes in cancer and other adult populations [66]. Ten randomized controlled trials with cancer patients have tested existential therapies, with four interventions focusing specifically on MiL. The results showed that meaning-centered interventions, compared with no intervention, can have a large effect on MiL and a moderate effect on distress. In contrast, few studies have examined intervention effects on SOC. Intervening on SOC may not be feasible if it is indeed a stable personality trait as posited by Antonovsky [8]. However, two studies showed that mindfulness-based stress reduction can increase cancer patients’ SOC as well as reduce their distress [34,35]. Additional intervention studies are needed to examine the extent to which SOC can be altered. Based on the current findings, meaning-centered interventions may be enhanced by incorporating unique components of SOC, such as the manageability of life circumstances. For example, cancer patients’ perceived manageability of their diagnosis could be increased through training in relaxation and other coping techniques. Lastly, based on moderator analyses, MiL and/or SOC interventions may be equally important for patients regardless of age, gender, religious status, cancer stage, and phase of the disease trajectory.

In conclusion, many cancer patients experience high rates of distress, and theory and research suggest that MiL and SOC play important roles in the psychological adjustment to cancer [1,7,8]. The current study found that moderate MiL-distress and large SOC-distress associations occur across many demographic and medical subgroups. Given the strength of the SOC-distress association, future meaning-centered intervention studies should consider incorporating components of Antonovsky’s salutogenic model [8]. Specifically, cancer patients’ distress may be reduced through enhancing their view that life is meaningful and comprehensible as well as manageable.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The work of the first author was supported by a fellowship from the Behavioral Cooperative Oncology Group Center for Symptom Management and the Walther Cancer Foundation. The work of the second author was supported by R25 CA117865-06 (V. Champion, PI) from the NCI. The work of the third author was supported by K07CA168883 from the NCI; in addition, research reported in this publication was supported by K05CA175048 from the NCI. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Kevin Rand, Ph.D., John McGrew, Ph.D., and Kenny Karyadi, M.S. for their assistance with this project.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web site.

References

- 1.Miovic M, Block S. Psychiatric disorders in advanced cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:1665–1676. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22980. DOI:10.1002/cncr.22980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linden W, Vodermaier A, MacKenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025. DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith E, Gomm S, Dickens C. Assessing the independent contribution to quality of life from anxiety and depression in patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med. 2003;17:509–513. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm781oa. DOI:10.1191/0269216303pm781oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinquart M, Duberstein P. Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1797–1810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992285. DOI:10.1017/S0033291709992285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giese-Davis J, Collie K, Rancourt KM, Neri E, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Decrease in depression symptoms is associated with longer survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a secondary analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:413–420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4455. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Visser A, Garssen B, Vingerhoets A. Spirituality and well-being in cancer patients: a review. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19:565–572. doi: 10.1002/pon.1626. DOI:10.1002/pon.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park CL. Making sense of the meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychol Bull. 2010;136:257–301. doi: 10.1037/a0018301. DOI:10.1037/a0018301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antonovsky A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp) Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:49–58. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06. DOI:10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klinger E. Meaning and Void: Inner Experience and the Incentives in peoples’ Lives. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis, MN: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumeister RF. Meanings of Life. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryff C. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57:1069–1081. DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frankl VE. Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy. Pocket Books; New York, NY: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yalom ID. Existential Psychotherapy. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reker GT, Peacock EJ, Wong PT. Meaning and purpose in life and well-being: A life-span perspective. J Gerontol. 1987;42:44–49. doi: 10.1093/geronj/42.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy PE, Fitchett G, Stein K, Portier K, Crammer C, Peterman AH. An examination of the 3-factor model and structural invariance across racial/ethnic groups for the FACIT-Sp: a report from the American Cancer Society’s Study of Cancer Survivors-II (SCS-II) Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19:264–272. doi: 10.1002/pon.1559. DOI:10.1002/pon.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. Eur J Pers. 1987;1:141–169. DOI:10.1002/per.2410010304. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schreiber JA, Brockopp DY. Twenty-five years later—what do we know about religion/spirituality and psychological well-being among breast cancer survivors? A systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:82–94. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0193-7. DOI:10.1007/s11764-011-0193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gustavsson-Lilius M, Julkunen J, Keskivaara P, Hietanen P. Sense of coherence and distress in cancer patientsand their partners. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16:1100–1110. doi: 10.1002/pon.1173. DOI:10.1002/pon.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyphantis T, Papadimitriou I, Petrakis D, et al. Psychiatric manifestations, personality traits and health-related quality of life in cancer of unknown primary site. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:2009–2015. doi: 10.1002/pon.3244. DOI:10.1002/pon.3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Black EK, White CA. Fear of recurrence, sense of coherence and posttraumatic stress disorder in haematological cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2005;14:510–515. doi: 10.1002/pon.894. DOI:10.1002/pon.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtis RC. Coping with Prostate Cancer: The Effects of Family Strength, Sense of Coherence, and Spiritual Resources. University of North Carolina at Greensboro; US: 2000. Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steger MF. Experiencing meaning in life: optimal functioning at the nexus of well-being, psychopathology, and spirituality. In: Wong PT, editor. The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications. Routledge; New York, NY: 2013. pp. 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherman AC, Simonton S, Latif U, Bracy L. Effects of global meaning and illness-specific meaning on health outcomes among breast cancer patients. J Behav Med. 2010;33:364–377. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9267-7. DOI:10.1007/s10865-010-9267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36:725–733. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-z. DOI:10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandstätter M, Baumann U, Borasio GD, Fegg MJ. Systematic review of meaning in life assessment instruments. Psycho-Oncology. 2012;21:1034–1052. doi: 10.1002/pon.2113. DOI:10.1002/pon.2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ebersole P, DePaola S. Meaning in life depth in the active married elderly. J Psychol. 1989;123:171–178. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1989.10542973. DOI:10.1080/00223980.1989.10542973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snekkevik H, Anke AG, Stanghelle JK, Fugl-Meyer AR. Is sense of coherence stable after multiple trauma? Clin Rehabil. 2003;17:443–452. doi: 10.1191/0269215503cr630oa. DOI:10.1191/0269215503cr630oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schnyder U, Büchi S, Sensky T, Klaghofer R. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence: trait or state? Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69:296–302. doi: 10.1159/000012411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinquart M, Fröhlich C. Psychosocial resources and subjective well-being of cancer patients. Psychol Health. 2009;24:407–421. doi: 10.1080/08870440701717009. DOI:10.1080/08870440701717009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park CL, Edmondson D, Fenster JR, Blank TO. Meaning making and psychological adjustment following cancer: the mediating roles of growth, life meaning, and restored just-world beliefs. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:863–875. doi: 10.1037/a0013348. DOI:10.1037/a0013348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breitbart W, Poppito S, Rosenfeld B, et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1304–1309. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2517. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Gibson C, et al. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19:21–28. doi: 10.1002/pon.1556. DOI:10.1002/pon.1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matousek R, Dobkin P. Weathering storms: a cohort study of how participation in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program benefits women after breast cancer treatment. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:62–72. doi: 10.3747/co.v17i4.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shapiro SL, Bootzin RR, Figueredo AJ, Lopez AM, Schwartz GE. The efficacy of mindfulness-based stress reduction in the treatment of sleep disturbance in women with breast cancer: an exploratory study. Psycho-Oncology. 2003;54:85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00546-9. DOI:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park CL, George LS. Assessing meaning and meaning making in the context of stressful life events: measurement tools and approaches. J Posit Psychol. 2013;8:483–504. DOI:10.1080/17439760.2013.830762. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peterman AH, Reeve CL, Winford EC, et al. Measuring meaning and peace with the FACIT–Spiritual Well-Being Scale: Distinction without a difference? Psychol Assess. 2014;26:127–137. doi: 10.1037/a0034805. DOI:10.1037/a0034805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferraro KF, Koch JR. Religion and health among black and white adults: examining social support and consolation. J Sci Study Relig. 1994;33:362–375. DOI:10.2307/1386495. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson KS, Elbert-Avila KI, Tulsky JA. The influence of spiritual beliefs and practices on the treatment preferences of African Americans: a review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:711–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53224.x. DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crawley L, Payne R, Bolden J, Payne T, Washington P, Williams S. Palliative and end-of-life care in the African American community. JAMA. 2000;284:2518–2521. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2518. DOI:10.1001/jama.284.19.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cancer Staging Fact Sheet. National Cancer Institute; [Accessed October 17, 2014]. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/detection/staging. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons; West Sussex, UK: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical Meta-analysis. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: A meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:160–174. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rabkin JG, McElhiney M, Moran P, Acree M, Folkman S. Depression, distress and positive mood in late-stage cancer: a longitudinal study. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18:79–86. doi: 10.1002/pon.1386. DOI:10.1002/pon.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ziegler L, Hill K, Neilly L, et al. Identifying psychological distress at key stages of the cancer illness trajectory: a systematic review of validated self-report measures. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2011;41:619–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.06.024. DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simonelli LE, Fowler J, Maxwell GL, Andersen BL. Physical sequelae and depressive symptoms in gynecologic cancer survivors: meaning in life as a mediator. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35:275–284. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9029-8. DOI:10.1007/s12160-008-9029-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Card NA. Applied Meta-analysis for Social Science Research. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilson DB. [Accessed October 17, 2014];Meta-analysis macros for SAS, SPSS, and Stata. 2010 http://mason.gmu.edu/~dwilsonb/ma.html.

- 51.Rosenthal R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psycho-Oncology. 1979;86:638–641. DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mizuno M, Kakuta M, Inoue Y. The effects of sense of coherence, demands of illness, and social support on quality of life after surgery in patients with gastrointestinal tract cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36:E144–E152. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.E144-E152. DOI:10.1188/09.ONF.E144-E152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lazenby M, Khatib J, Al-Khair F, Neamat M. Psychometric properties of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-being (FACIT-Sp) in an Arabic-speaking, predominantly Muslim population. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:220–227. doi: 10.1002/pon.2062. DOI:10.1002/pon.2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jim HS, Andersen BL. Meaning in life mediates the relationship between social and physical functioning and distress in cancer survivors. Br J Health Psychol. 2007;12:363–381. doi: 10.1348/135910706X128278. DOI:10.1348/135910706X128278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gibson LM, Parker V. Inner resources as predictors of psychological well-being in middle-income African American breast cancer survivors. Cancer Control. 2003;10:52–59. doi: 10.1177/107327480301005s08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alcorn SR, Balboni MJ, Prigerson HG, et al. ‘If God wanted me yesterday, I wouldn’t be here today’: religious and spiritual themes in patients’ experiences of advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:581–588. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0343. DOI:10.1089/jpm.2009.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dull VT, Skokan LA. A cognitive model of religion’s influence on health. J Soc Issues. 1995;51:49–64. DOI:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1995.tb01323.x. [Google Scholar]

- 58.McIntosh DN. Religion-as-schema, with implications for the relation between religion and coping. Int J Psychol Relig. 1995;5:1–16. DOI:10.1207/s15327582ijpr0501_1. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hill PC, Pargament KI. Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality: implications for physical and mental health research. Psycholog Relig Spiritual. 2008;3-17 doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.64. DOI:10.1037/1941-1022.S.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Janoff-Bulman R. Shattered Assumptions: Towards a New Psychology of Trauma. Simon and Schuster; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Büssing A, Fischer J. Interpretation of illness in cancer survivors is associated with health-related variables and adaptive coping styles. BMC Womens Health. 2009;9:2–11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-9-2. DOI:10.1186/1472-6874-9-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ibbotson T, Maguire P, Selby P, Priestman T, Wallace L. Screening for anxiety and depression in cancer patients: the effects of disease and treatment. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30:37–40. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80015-2. DOI:10.1016/S0959-8049(05)80015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manjer J, Merlo J, Berglund G. Validity of self-reported information on cancer: determinants of under- and over-reporting. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:239–247. doi: 10.1023/b:ejep.0000020347.95126.11. DOI:10.1023/B:EJEP.0000020347.95126.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Phillips K-A, Milne RL, Buys S, et al. Agreement between self-reported breast cancer treatment and medical records in a population-based Breast Cancer Family Registry. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4679–4686. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.002. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhu K, McKnight B, Stergachis A, Daling JR, Levine RS. Comparison of self-report data and medical records data: results from a case-control study on prostate cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:409–417. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.3.409. DOI:10.1093/ije/28.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vos J, Craig M, Cooper M. Existential therapies: a meta-analysis of their effects on psychological outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. doi: 10.1037/a0037167. In Press. DOI:10.1037/a0037167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.