Abstract

Progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia (PPRD) is a rare, autosomal recessive condition characterized by mild spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia and severe, progressive, early-onset arthritis due to WISP3 mutations. Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia (SED), Stanescu type, is a vaguely delineated autosomal dominant dysplasia of unknown genetic etiology. Here we report three individuals from two unrelated families with radiological features similar to PPRD and SED, Stanescu type who share the same novel COL2A1 variant and were matched following discussion at an academic conference. In the first family, we performed whole exome sequencing on three family members, two of whom have a PPRD-like phenotype, and identified a heterozygous variant (c.619G>A, p.Gly207Arg) in both affected individuals. Independently, targeted sequencing of the COL2A1 gene in an unrelated proband with a similar phenotype identified the same heterozygous variant. We suggest that the p.Gly207Arg variant causes a distinct type II collagenopathy with features of PPRD and SED, Stanescu type.

Keywords: COL2A1, Skeletal dysplasia, type II collagenopathy, PPRD, SED, Stanescu

Progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia (PPRD; MIM# 208230), is a painful, disabling autosomal recessive skeletal dysplasia accompanied by pseudorheumatoid arthritis that manifests in childhood and inexorably worsens. Features include platyspondyly, epimetaphyseal expansion, and progressive stiffness and swelling of the joints [Garcia Segarra et al., 2012]. Hurvitz et al. [1999] implicated variants in WISP3 (Wnt-1-inducible secreted protein 3; MIM# 603400) in several families with PPRD; however, no WISP3 variants were found in a simplex case in this cohort (Family 6), suggesting locus heterogeneity.

Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia (SED), Stanescu type, is distinguished by painful, progressive joint space narrowing, joint contractures, platyspondyly, and epimetaphyseal dysplasia with pronounced femoral coxa valga and normal stature. This disorder was first described by Stanescu et al. [1984] in a male proband born of unaffected parents, making the mode of inheritance indeterminate. Subsequently, Nishimura et al. [1998] described two families with multiple affected generations and autosomal dominant transmission. As noted by Nishimura et al. [1998], SED, Stanescu type is likely underdiagnosed, perhaps due to shared features with other dysplasias. Neither the genetic basis of this disorder nor is its relationship to PPRD is clear.

Czech dysplasia [Marik et al., 2004; MIM# 609162] is caused by a heterozygous c.823C>T, p.Arg275Cys variant in the type II alpha-1 collagen gene COL2A1 (MIM# 120140). While also characterized by early-onset, progressive arthritis and skeletal dysplasia, it is clinically distinguishable from PPRD by shortened metatarsals in all described individuals.

Here we describe three patients from two families harboring a novel heterozygous variant in COL2A1 (RefSeq NM_001844.4:c.619G>A, p.Gly207Arg), with similar phenotypes. The proband of Family 1 (Table 1) was previously reported as the simplex case of family 6 by Hurvitz et al. [1999]. She is the product of unaffected, non-consanguineous parents with negative family histories for relevant features. As a child, she was noted never to hop or run. A waddling gait was initially assessed at 4 years of age, prompting concerns of limb weakness, but extensive evaluation demonstrated no neuromuscular abnormality. Joint pain began around 5 years of age. More severe joint pain and early joint immobility arose in late childhood and were initially most severe in her neck and spine.

Table 1. Comparison of Clinical and Molecular Features of Relevant Disorders.

| Family 1 | Family 2 | Rukavina et al. [2014] | Czech Dysplasia | SED, Stanescu type |

Progressive Pseudorheumatoid Dysplasia (PPRD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode of Inheritance | Autosomal dominant |

De novo | Autosomal dominant |

Autosomal dominant |

Autosomal dominant |

Autosomal recessive |

|

| ||||||

| Family Origin | U.S.A. | Korea | Unknown | Multiethnic | Multiethnic | Multiethnic |

|

| ||||||

| Major Clinical Features | ||||||

| Short Stature | + | − | + | − | − | + |

|

| ||||||

| 3rd and 4th Toe Shortening |

− | − | − | +* | − ** | − |

|

| ||||||

| Hearing Loss | − | − | − | +/− | +/−*** | − |

|

| ||||||

| Joint Pain | + | + | + | + | + | + |

|

| ||||||

| Progressive Joint Immobility |

+ | + | + | + | + | + |

|

| ||||||

| Joint Replacement Surgery Needed |

+ | Not yet | + | + | + | + |

|

| ||||||

| Major Radiologic Features | ||||||

| Progressive Platyspondyly |

+ | + | + | + | + | + |

|

| ||||||

| Progressive Joint Space Narrowing |

+ | +***** | + | + | + | + |

|

| ||||||

| Metaphyseal Enlargement, Hands |

+ | − ****** | + | +/− | + | + |

|

| ||||||

| Metatarsal Shortening | − | − | − | +* | − | − |

|

| ||||||

| Mutated Gene | COL2A1 | COL2A1 | COL2A1 | COL2A1 | Unknown | WISP3 |

|

| ||||||

| Genetic Variant **** | c.619G>A (heterozygous) |

c.619G>A (heterozygous) |

c.611G>T (heterozygous) |

c.823C>T (heterozygous) |

N/A | Allelic Heterogeneity [Hurvitz et al., 1999; Delague et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2007; Yue et al., 2009; Temiz et al., 2011; Dalal et al., 2012; Garcia Segarra et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2012] |

|

| ||||||

| Protein Variant **** | p.Gly207Arg (heterozygous) |

p.Gly207Arg (heterozygous) |

p.Gly204Val (heterozygous) |

p.Arg275Cys (heterozygous) |

N/A | Allelic Heterogeneity (See references above) |

|

| ||||||

| SIFT/ PolyPhen-2 Scores | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/0.999 | 0/0.999 | N/A | N/A |

Although the patients described by Burrage et al. [2013] did not have disproportionate shortening of the 3rd and 4th toes, they did have radiologic evidence of generalized shortening of the metatarsals.

One proband described by Nishimura et al. [1998] had shortening of his 2nd and 3rd toes and 2nd fingers; this is distinct from the 3rd and 4th toe shortening observed in Czech dysplasia.

The original proband described by Stanescu et al. [1984] had sensorineural hearing loss.

COL2A1 variant positions are based on RefSeq transcript NM_001844.4.

After age 10 years.

As of age 10 years.

Although radiographs at 9 years of age showed mild platyspondyly, anterior vertebral wedging and mild, generalized epiphyseal abnormalities, she carried a diagnosis of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis throughout childhood. She developed kyphoscoliosis in adolescence and had extension osteotomies of both femora at age 13 years due to worsening hip flexion contractures.

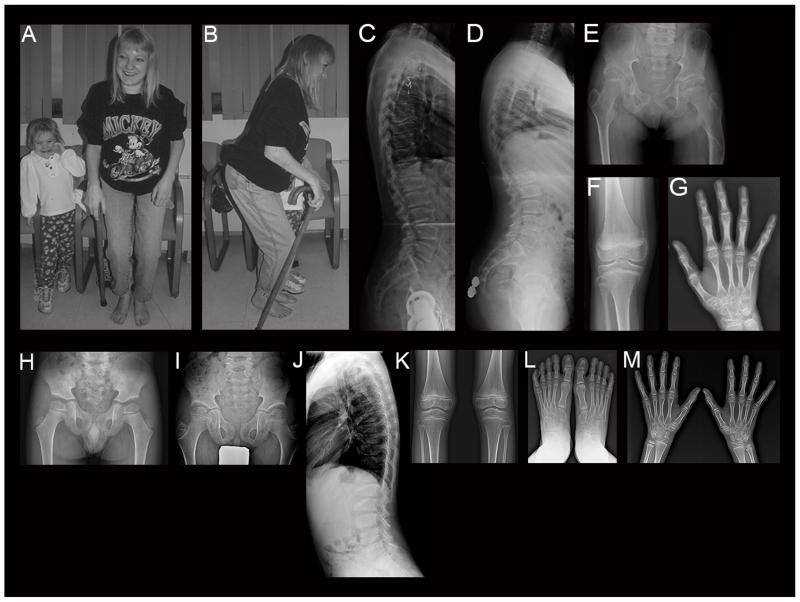

She was first evaluated through the Midwest Regional Bone Dysplasia Clinics at age 22 years (Fig. 1a-c). Between childhood and her first assessment, joint pain progressively worsened, with greatest severity in her elbows, hips, knees and hands. Progressive joint stiffness and joint prominence developed, particularly in her hands. She had an adult height of ~150 cm, generalized truncal stiffness, severe neck stiffness, normal craniofacial features, and limited mouth opening. Shoulder abduction and elevation as well as elbow extension, pronation and supination were limited. Legs showed hip flexion contractures, only 15° of rotation, no abduction or adduction, minimal active hip flexion, mild knee flexion contractures, and ankle stiffness. Her stance was a “Z” posture (Fig. 1a-b) with absent heel strike, knee flexion, and hip flexion. Spine radiographs showed platyspondyly and anterior wedging (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

a-c: Proband of Family 1 at 23 years. Note marked joint contractures resulting in Z posture. c: Lateral spine radiograph shows platyspondyly and irregular degenerative changes. d-g: Radiographs of the daughter of the proband of Family 1 at 12 years. d: Mild anterior wedging and platyspondyly of lateral spine. e: Hip and pelvic features include flattened and irregular femoral heads, short femoral necks, and deformed shaft of the left femur secondary to prior trauma. f: Knee radiograph shows joint space narrowing and metaphyseal irregularity. g: Note metaphyseal prominence and joint space narrowing at distal radius and distal ulna. h-m: Radiographs of the proband of Family 2 at 4 years (h) and 8 years (i-m). h: Note irregularity and mild flattening at articular surfaces of capital femoral epiphyses. Acetabulum is flat, and femoral necks are broad with mild coxa valga. i: Capital femoral epiphyses show mild flattening and dysplastic trabeculation. Femoral necks are broad and elongated with further coxa valga. Ilia are somewhat narrowed and elongated. The acetabulum shows deepening with irregularity of its contour. j: Note moderate spinal platyspondyly with anterior wedging and irregularity of the endplates. k: Knee joints show mild flaring of the distal femora and proximal tibiae. Epiphyses are normal. l-m: Hands and feet are normal.

Over the ensuing ten years, her stiffness and pain worsened, requiring bilateral hip replacements at age 25 years and knee replacements at age 26 years. She developed progressive thoracolumbar kyphosis and presented acutely at age 35 years with progressive numbness to the level of the umbilicus and leg weakness. MRI showed severe spinal stenosis and multilevel myelomalacia. She had laminectomy (T8-L1 and L4-L5) and spinal fusion, which improved her symptoms. Today, she is 38 years old and remains ambulatory.

She was initially diagnosed with PPRD and included in the cohort of Hurvitz et al. [1999], but had no pathogenic WISP3 variants, which was confirmed by subsequent testing (Supp. Materials and Methods). A diagnosis of Czech dysplasia was also considered but rejected due to the absence of structural abnormalities of the toes or metatarsals.

Concerns arose in the proband’s daughter (Table 1) during childhood. She was born at 36 weeks gestation with a weight of 2840 g and length of 48 cm. When first assessed at 3 7/12 years of age, her mother was concerned about a mild waddling gait, but examination was normal. By 5 years of age, she had progressive knee valgus, internal tibial torsion, mild limitation of ankle dorsiflexion, and poor heel-toe transition, but was otherwise normal. Between 7 and 8 ½ years of age, neck stiffness, minimal limitation of elbow supination, and minimal wrist stiffness were evident, as were confounding features caused by an unrelated subtrochanteric femur fracture.

By age 11 ½ years, she had developed worsening neck stiffness; pain in her neck, hips, and knees; increased waddling; and decreased walking endurance. She had decreased mobility in her neck, elbows, wrists, hips, knees, and ankles. Proximal interphalangeal hand joints were prominent, and feet were normal except for incidental mild hallux valgus. Height was 135.4 cm (5th centile). Between 12-15 years of age, kyphosis developed, mild scoliosis progressed, and joint stiffness and pain worsened, particularly in her hips. She is now a young adult and attends college. Joint immobility, particularly of the hips and knees, has continued to progress. She has severe pain with ambulation and can only walk for short distances with crutches. Both hip replacement and spinal fusion surgeries are anticipated.

Radiographs at 5 and 8 years of age were normal. By 12 years of age, her spine showed mild to moderate generalized platyspondyly, mild anterior wedging, loss of anterior substance and mild excess concavity of the vertebral bodies, and a lumbar scoliosis (Fig. 1d). There was mild, generalized joint space narrowing and metaphyseal irregularity (distal radii, distal ulnae, and distal femora; Fig. 1e-g), and phalangeal metaphyses of the hands were mildly prominent (Fig. 1g). Femoral heads were flattened and irregular, and femoral necks were short (Fig. 1e). The left femur was deformed secondary to previous injury.

The proband of Family 2 (Table 1) is a Korean boy who presented at age 6 years because of awkward gait and running difficulty. He was the product of a normal full-term pregnancy of unaffected, non-consanguineous parents and born with a weight of 3.7 kg. Motor and cognitive developments were normal, and he started to walk alone at 14 months of age. His parents noticed his slow, waddling gait and inability to run at 2-3 years of age. He was examined by a pediatric neurologist but not found to have neurologic or muscle disease. His height was 118.3 cm (z=+0.6, 73th centile), and weight 18.4 kg. His older brother and sister were unaffected. At age 8 ½ years, he had an awkward gait and complained of difficulty squatting. He could run only slowly, and could barely climb stairs without the railing. Physical assessment revealed standing posture with hips and knees flexed. He showed a wide-based gait with smooth heel-toe progression. The knees showed 20° flexion contractures. The hips and elbows showed mild limitation of motion. His height was 131.5 cm (z=+0.45, 67th centile) and arm span was 137 cm.

At 9 4/12 years of age, his knee and hip joint pain worsened, precluding sports activities. He had a stiff gait with hip abduction. The hip joints showed 15° flexion contractures, and further flexion was painful and limited to 100°. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories and diverse physical treatments lessened his joint pain. By 10 ½ years of age, he could walk only with assistance due to joint pain and limb muscle weakness from prolonged disuse. Bearing weight on his legs resulted in hip, knee, and ankle pain. Motion at the hip joint was painful, with flexion contractures of 20° and flexion limited to 120°. The knee joint showed 20° flexion contractures.

His initial hip radiographs at 4 years of age (Fig. 1h) showed irregular contour of the femoral capital epiphyses, shallow acetabulum, and wide femoral neck with mild coxa valga. Skeletal survey at age 8 ½ years (Fig. 1i-m) revealed generalized platyspondyly with wedged vertebral bodies at the thoracolumbar junction. His pelvis showed mild capital femoral epiphyseal dysplasia, coxa valga, and small, elongated ilia. Hand radiographs showed no distinct metaphyseal widening of the phalanges or metacarpals. Feet lateral radiographs showed large os trigonum bilaterally, and accentuated pes cavus. We prioritized a diagnosis of SED, Stanescu type and also included a broad category of unclassified spondyloepiphyseal dysplasias, possibly including a type II collagenopathy. Based on the proband’s average to tall stature, apparent spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia with coxa valga, and absent metaphyseal widening of the phalanges, there was no initial suspicion of PPRD.

After multiple assessments failed to detect WISP3 variants in Family 1, we performed WES on the proband, her unaffected mother, and her affected daughter. WES analysis and filtering in Family 1 (Supp. Materials and Methods) yielded 56 heterozygous variants, including a novel COL2A1 variant (p.Gly207Arg). Sanger sequencing confirmed that this variant was present in the 2 affected individuals and absent in the unaffected mother of the proband (Supp. Figure S1), but we were unable to confirm de novo occurrence in the proband since paternal DNA was unavailable. In the proband of Family 2, we directly evaluated COL2A1 for sequence and copy number variants because we suspected a type II collagenopathy (Supp. Materials and Methods). We detected the same heterozygous variant in the proband by full Sanger sequencing of COL2A1 (Supp. Table S1) and confirmed de novo occurrence by Sanger sequencing of the mutation site in his unaffected parents (Supp. Figure S2). Functional prediction software indicates that the variant occurs at a conserved residue and is predicted to be damaging (Supp. Materials and Methods). This variant was submitted to a COL2A1 locus-specific database at http://databases.lovd.nl/shared/variants/COL2A1, DB-ID COL2A1_000405, in three separate entries representing each individual with the variant.

Interestingly, the clinical and radiological findings manifest somewhat differently between affected individuals in Families 1 and 2, although they share the same variant. The proband of Family 2 exhibited normal height until late childhood, and the proximal femora were broad and elongated with coxa valga. The proband of Family 2 also lacked enlarged phalangeal epimetaphyses of the hands, which is one of the hallmarks of PPRD and was prominent in Family 1.

COL2A1 encodes the alpha-1 chain of type II collagen, the primary collagen in articular cartilage. Many bone dysplasias are type II collagenopathies (MIM# 120140), ranging from lethal to very mild and including Czech dysplasia. Although the individuals described here share many phenotypic features and the autosomal dominant mode of inheritance of Czech dysplasia, they lack major hallmarks including metatarsal shortening, which is thought to be uniformly characteristic of Czech dysplasia (Table 1). In addition, a single heterozygous COL2A1 variant (p.Arg275Cys) has been ascribed to Czech dysplasia in all published cases (MIM# 609162), while the individuals described here are heterozygous for a p.Gly207Arg variant.

Although there are few reports of Stanescu dysplasia, all describe a chondrocytic phenotype of PAS-positive, amylase-resistant cytoplasmic inclusions [Stanescu et al., 1984; Nishimura et al., 1998]. Since we did not have access to chondrocytes from our patients, we were unable to test for this feature. However, given the phenotypic overlap with our cases, it is likely that Stanescu dysplasia is also a type II collagenopathy, and conceivable that it arises from the same mutation described here. We believe it would be worthwhile to investigate the possibility of COL2A1 mutation in other cases with this phenotype.

Rukavina et al. [2014] implicated a c.611G>T, p.Gly204Val COL2A1 variant in a case of early-onset progressive osteoarthritis with mild spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia (Table 1). This patient shares many clinical features of the patients described here, suggesting similar consequences of the p.Gly204Val and p.Gly207Arg COL2A1 variants.

Previous connections have been made between WISP3 and type II collagen. Overexpression of wild-type WISP3, but not PPRD variants, increases type II collagen in human chondrocytes [Sen et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2013]. WISP3 normally co-localizes with type II collagen in the midzone region of chondrocytes, but WISP3 localization is disrupted by PPRD variants [Sen et al., 2004]. Type II collagen secretion into the extracellular matrix also decreases in human chondrocytes transfected with mutant as compared to wild-type WISP3 [Wang et al., 2013]. We hypothesize that the WISP3 variants found in PPRD and the COL2A1 variant described here both decrease type II collagen, potentially disrupting the extracellular matrix and common downstream signaling pathways [Barber et al., 2014].

These individuals heterozygous for the p.Gly207Arg COL2A1 variant have a phenotype overlapping PPRD, SED, Stanescu type, and Czech dysplasia, although the third is clinically distinguishable by metatarsal shortening. The individuals described here have a disorder that further expands the phenotypic spectrum of type II collagenopathies.

We initially matched the common variant in these families at an academic conference. The team working with the proband of Family 2 described the variant in an abstract, which was subsequently recognized by the group following Family 1. While this story highlights the power of case matching, the probability that such matches will be made is enhanced by tools such as GeneMatcher [Sobreira et al., 2015]. Based on our experience, we strongly support wider collaboration and data sharing, particularly for researchers and clinicians following rare disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our patients and their families for participation and to Dr. James Hyland of Connective Tissue Gene Tests for molecular analysis of WISP3 in Family 1. Our work was supported in part by grants from the US NIH/NHGRI (T32GM07814; 1U54HG006542) and the Genome Technology to Business Translation Program of the National Research Foundation funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning of the Korean Government (NRF-2014M3C9A2064684).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barber T, Esteban-Pretel G, Marin MP, Timoneda J. Vitamin A deficiency and alterations in the extracellular matrix. Nutrients. 2014;6:4984–5017. doi: 10.3390/nu6114984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrage LC, Lu JT, Liu DS, Moss TJ, Gibbs R, Schlesinger AE, Bacino CA, Campeau PM, Lee BH. Early childhood presentation of Czech dysplasia. Clin Dysmorphol. 2013;22:76–80. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0b013e32835fff39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal A, Bhavani GSL, Togarrati PP, Bierhals T, Nandineni MR, Danda S, Danda D, Shah H, Vijayan S, Gowrishankar K, Phadke SR, Bidchol AM, et al. Analysis of the WISP3 gene in Indian families with progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A(11):2820–2828. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delague V, Chouery E, Corbani S, Ghanem I, Aamar S, Fischer J, Levy-Lahad E, Urtizberea JA, Mégarbané A. Molecular study of WISP3 in nine families originating from the Middle-East and presenting with progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia: identification of two novel mutations, and description of a founder effect. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;138A(2):118–126. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Segarra N, Mittaz L, Campos-Xavier AB, Bartels CF, Tuysuz B, Alanay Y, Cimaz R, Cormier-Daire V, Di Rocco M, Duba HC, Elcioglu NH, Forzano F, et al. The diagnostic challenge of progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia (PPRD): A review of clinical features, radiographic features, and WISP3 mutations in 63 affected individuals. Am J Med Genet C. 2012;15:217–229. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurvitz JR, Suwairi WM, Van Hul W, El-Shanti H, Superti-Furga A, Roudier J, Holderbaum D, Pauli RM, Herd JK, Van Hul E, Rezai-Delui H, Legius E, et al. Mutations in the CCN gene family member WISP3 cause progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia. Nat Genet. 1999;23:94–98. doi: 10.1038/12699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marik I, Marikova O, Zemkova D, Kuklik M, Kozlowski K. Dominantly inherited progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia with hypoplastic toes. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33:157–164. doi: 10.1007/s00256-003-0708-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura G, Saitoh Y, Okuzumi S, Imaizumi K, Hayasaka K, Hashimoto M. Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia with accumulation of glycoprotein in the chondrocytes: spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, Stanescu type. Skeletal Radiol. 1998;27:188–194. doi: 10.1007/s002560050363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM . McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University; Baltimore, MD: [Accessed October 2013]. http://omim.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rukavina I, Mortier G, Van Laer L, Frković M, Ðapić T, Jelušić M. Mutation in the type II collagen gene (COL2AI) as a cause of primary osteoarthritis associated with mild spondyloepiphyseal involvement. Semin Arthritis Rheu. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.03.003. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.03.003. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen M, Cheng Y, Goldring MB, Lotz MK, Carson DA. WISP3-dependent regulation of type II collagen and aggrecan production in chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:488–497. doi: 10.1002/art.20005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobreira N, Schiettecatte F, Boehm C, Valle D, Hamosh A. New tools for Mendelian disease gene identification: PhenoDB variant analysis module; and GeneMatcher, a web-based tool for linking investigators with an interest in the same gene. Hum Mutat. 2015;36(4):425–431. doi: 10.1002/humu.22769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanescu R, Stanescu V, Maroteaux P. Dysplasie Spondylo-epiphysaire avec accumulation de glycoproteines dans les chondrocytes. Arch Fr Pediatr. 1984;41:185–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Xia W, He S, Zhao Z, Nie M, Li M, Jiang Y, Xing X, Wang O, Meng X, Zhou X. Novel and recurrent mutations of WISP3 in two Chinese families with progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temiz F, Ozbek MN, Kotan D, Sangun O, Mungan NO, Yuksel B, Topaloglu AK. A homozygous recurring mutation in WISP3 causing progressive pseudorheumatoid arthropathy. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2011;1-2:105–108. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2011.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Man XF, Liu YQ, Liao EY, Shen ZF, Luo XH, Guo LJ, Wu XP, Zhou HD. Dysfunction of collagen synthesis and secretion in chondrocytes induced by Wisp3 mutation. Int J Endocrinol. 2013;2013:679763. doi: 10.1155/2013/679763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue H, Zhang ZL, He JW. Identification of novel mutations in WISP3 gene in two unrelated Chinese families with progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia. Bone. 2009;44:547–554. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HD, Bu YH, Peng YQ, Xie H, Wang M, Yuan LQ, Jiang Y, Li D, Wei QY, He YL, Xiao T, Ni JD, Liao EY. Cellular and molecular responses in progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia articular cartilage associated with compound heterozygous WISP3 gene mutation. J Mol Med. 2007;85:985–996. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0193-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.