Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a devastating neurodegenerative condition that affects more than 5 million Americans. Currently, a definitive and unequivocal diagnosis of AD can only be confirmed histopathogically via post-mortem autopsy, demonstrating the need for objective measures of cognitive functioning for those at risk for AD. The single most important genetic risk factor of AD is the Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) ε4 allele. The present study investigated olfactory and cognitive processing deficits in ApoE ε4 positive individuals using a cross-modal recognition memory task and an objective electrophysiological measure, the event-related potential (ERP). Ten ε4+ individuals (5 M, 5 F, M = 75.1 yrs) and ten age and gender-matched ε4− individuals (5 M, 5 F, M = 71 yrs) sequentially encoded a set of 16 olfactory stimuli and were subsequently shown names of odors previously presented (targets) or not (foils). EEG activity was recorded from 19 electrodes as participants distinguished targets from foils using a two-button mouse. P3 latencies were significantly longer in ε4+ individuals and intra-class correlations demonstrated differential activity between the two groups. These findings are consistent with a compensatory hypothesis, which posits that non-demented ε4+ individuals will expend greater effort in cognitive processing or engage in alternative strategies and therefore require greater activation of neural tissue or recruitment of different neural populations. The findings also suggest that cross-modal ERP studies of recognition memory discriminate early neurocognitive changes in ApoE ε4+ and ApoE ε4− individuals and may contribute to identifying the phenotype of persons who will develop Alzheimer's Disease.

Keywords: Aging, Alzheimer's Disease, ApoE ε4, Olfaction, Olfactory Impairment, Smell, Recognition Memory

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a devastating neurodegenerative condition that affects more than 5 million Americans. Since 1980, the prevalence of AD in America has nearly doubled making it the most common form of dementia, accounting for 50-60% of dementia related cases. Current estimates suggest that by 2050, more than 13 million Americans will suffer from this debilitating disorder.1

Diagnostic Criteria

Both the NINDS-ADRDA and the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for AD include progressive and global cognitive impairment in two or more cognitive areas including memory. Attempts to diagnose the disorder in a living person using physiological tests are imperfect. Therefore, a definitive and unequivocal diagnosis of AD can only be confirmed histopathogically via post-mortem autopsy. As pharmacological and other interventions become available, distinguishing very early those individuals who will go on to develop AD will be very important for targeted treatment; hence, efforts to identify these individuals are keen. The current study was designed to investigate a new method for targeting these individuals using evoked brain potentials.

Risk Factors

A number of risk factors for AD have been identified with the most obvious being age,1,2 a decreased reserve capacity of the brain resulting from reduced brain size, low educational and occupational attainment, low mental ability in early life, and reduced mental and physical activity during later life,3,4 head trauma,5 and Down's syndrome.6,7

The single most important genetic risk factor is the allelic variant apolipoprotein E (ApoE) ε4.8 The ApoE ε4 allele increases the risk of developing AD by three times in heterozygotes and by fifteen times in homozygotes.9, 10

ApoE ε4

ApoE is a key lipoprotein found in the brain as well as the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF).11,12 It has been mapped in the human genome to the proximal long arm of Chromosome 19.13,14 ApoE normally functions as a cholesterol transporter in the brain12 but it also abnormally binds to soluble and insoluble forms of B-amyloid15 and the βA4 peptide, which is the primary component of neuritic plaques.16 As shown by Poirier,17 the ApoE ε4 allele is less efficient than other ApoE alleles in the reuse of membrane lipids and neuronal repair. ApoE has also been found to contribute to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs).11

ApoE mRNA, which plays a compensatory role in neuronal sprouting and synaptogenesis in the central nervous system, is reduced in the hippocampus in AD.15 Tau, the main component of NFTs, is elevated in the CSF of AD patients who possess at least one copy of the ε4 allele compared to those without the ε4 allele.18 Soininen and Riekkinen19 showed a positive association between the number of ε4 alleles and the increased deficit of acetylcholine-containing neurons in the brains of AD patients.

Prior research into global cognitive functioning and ApoE allele genotype has been inconclusive. A number of studies have shown that the ε4 allele predicted cognitive decline20-26 and ε4+ persons perform poorly on tests of processing speed, delayed free recall, and semantic long term memory.27 However, performance is not impaired on all tests28-30 and some have reported no difference in cognitive decline between the different allelic variants of ApoE.31,32

Olfaction and AD

AD produces neuropathological changes in peripheral and central areas of the brain that process olfactory information. The first stage in the neurodegenerative progression of AD occurs in the entorhinal and trans-entorhinal areas critical to olfactory information processing.33,34 The olfactory bulbs, anterior olfactory nucleus, and orbitofrontal cortex are all also affected by AD.34,35 This pathology motivates the investigation of olfactory functioning in individuals in the beginning stages of AD. The olfactory deficits observed in AD include decreases in odor threshold sensitivity,36-38 odor identification,39-42 odor memory,43,44 odor fluency,45 and olfactory event-related potentials.46

Deficits in olfactory functioning have also been associated with those at risk for AD. Wilson (this volume) discusses elegantly the olfactory impairment in persons with mild cognitive impairment, an important risk factor for AD. He and his group have also shown a significant relationship between olfactory impairment and neuroanatomical bases of AD. Olfactory deficits are clearly associated with the ApoE ε4 allele. Physiologically, a post-mortem study showed ApoE was localized in an increased number of olfactory receptor neurons becoming more pervasive in the olfactory epithelium of individuals with AD compared to non-AD individuals.47 Behaviorally, Bacon et al.36 demonstrated that in the first year of their AD diagnosis, ε4 + individuals had inferior odor threshold sensitivity. Murphy et al.42 showed that even in nondemented elderly individuals, those with the ε4 allele showed impaired odor identification, and Calhoun-Haney and Murphy48 found significant decline in odor identification in ε4 + individuals who did not yet show significant declines in DRS, suggesting that changes in olfactory function may predict later overall decline.

Memory

Neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies have revealed several different brain regions involved in encoding and retrieval of episodic memory. These studies demonstrated that neural activity is observed in different brain regions depending on a number of conditions, e.g., depth of encoding,49 sensory modality,50 and task set.51

Recognition Memory and ApoE

A number of studies have shown significant deficits in odor recognition memory and odor identification in ε4+ individuals.52-54 They also commit more false positive errors in response to olfactory stimuli than ε4− individuals.52 A false positive error is defined as erroneously choosing a new stimulus (foil) as a member of the original stimulus set (target). Analysis of false positive errors and poor performance on odor recognition memory tasks may be useful ways to distinguish between normal older individuals and those at risk for developing AD.

ERP Components

Early components of the ERP waveform, N1/P2, represent exogenous sensory mechanisms that have been associated with psychophysical measures of olfactory functioning, e.g., odor threshold sensitivity.57,58 Later components of the ERP waveform, especially P3, represent endogenous mechanisms such as stimulus classification speed as well as cognitive attending and evaluation of stimuli.59,60 P3 latency is correlated with performance on neuropsychological tests that measure memory and cognitive processing speed.61 P3 amplitude is proportional to the amount of neural resources allocated to a given task.62,63 P3 latency increases and P3 amplitude decreases as individuals age.57,58,64,65 Wetter and Murphy66 also demonstrated that ApoE ε4+ individuals performing an oddball task show abnormally increased P3 latency and decreased P3 amplitude. These findings suggest the potential of EEG measures for assessing cognitive functioning and more specifically recognition memory in ε4+ individuals.

However, to date, an ERP recognition memory study using a cross-modal odor recognition task (presenting olfactory stimuli during encoding and visually presenting names of those same odors during recognition) has never been employed to investigate differences in cortical activation in ApoE ε4+ and ε4− individuals. This was our aim.

Methods

Participants were 20 non-demented older adults, 10 who were ε4+ (5 M, 5 F, M = 75.1 years, SD = 8.3) and 10 who were ε4−, age- and gender matched (M = 71 years, SD = 6.1). All gave informed consent.

Psychophysical and Neuropsychological Measures

Psychophysical measures included the San Diego Odor Identification Test,70 measures of verbal fluency including letter and category fluency, and tests of odor fluency.45 The odor threshold test37 screened for potential anosmia or severe hyposmia.

Neuropsychological measures included the California Odor Learning Test (COLT), 71 the Dementia Rating Scale (DRS),72 and the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE).73 These measures assess participants’ global cognitive functioning, cognitive impairment, and odor learning, recall, and recognition memory abilities.

Electrophysiological Data Collection

Electroencephalographic (EEG) activity was recorded with an electrode cap from 19 electrode sites, FP1/2, Fz, F3/4, F7/8, Cz, C3/4, T7/8, Pz, P3/4, P7/8, and O1/2, for 2000 ms, including a 100 ms pre-stimulus baseline; amplified via a Grass RPS 197 amplifier system; filtered (0.1 30 Hz band pass, 6 dB octave/slope); and digitized at 256 Hz. Data were averaged off-line using in-house software to reject artifactual responses of +/− 150 μV and a regression analysis based EOG correction procedure to remove any remaining artifact.74 Neuroscan software was used to calculate intra-class correlations.

Procedure

The experimental paradigm used in this study is identical to the paradigm used in a parallel fMRI study investigating cross-modal recognition memory for odors,69 and is based on a design of Stark and Squire.50 Stimuli were presented in 3 blocks, each with 72 trials. During encoding, participants were presented with 16 familiar odors from the California Odor Learning Test.71 Each was presented for 5 sec, with a 15 sec inter-stimulus interval.

During EEG recording, every 4 sec participants were presented with words displayed on a computer screen that corresponded to names of odors previously presented (targets) or not (foils), followed by a fixation cross. Participants distinguished targets from foils using a two-button mouse.

Hypotheses

The purpose of the proposed study was to examine whether ApoE ε4+ and ε4− individuals exhibit differences in the neural allocation of resources during a cross-modal recognition memory task. We analyzed P3 latency and intra-class correlations of activity at each electrode site. We hypothesized differences in ERP data as a function of allele status: Longer P3 latencies, and differences in activity in ApoE ε4+ individuals, dependent on response type.

Results

Psychophysical and Cognitive Functioning Tests

Multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) on age, years of education, category fluency, odor fluency, letter fluency, mean odor threshold, SDOIT, DRS, and MMSE scores demonstrated no significant differences between groups (Table 1). In particular, analyses demonstrated no significant difference in odor threshold scores between ApoE ε4+ and ε4− participants. This finding suggests that ε4+ and ε4− participants had similar sensory functioning and therefore, similar potential to encode the olfactory stimuli. This result was not surprising since participants were screened to exclude participants with anosmia or severe hyposmia.

Table 1.

MANOVA Results for Psychophysical and Cognitive Function Tests

| Dependent Variables | ApoE ε4+ | ApoE ε4− | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | df | F | Sig. | |

| Age | 75.13 | 8.34 | 71.00 | 6.14 | 1 | 1.27 | .28 |

| Education (Years) | 14.38 | 2.61 | 14.63 | 2.26 | 1 | .04 | .84 |

| Category fluency score | 44.50 | 9.61 | 45.38 | 6.97 | 1 | .04 | .84 |

| Odor fluency score | 17.13 | 8.18 | 12.75 | 8.88 | 1 | 1.05 | .32 |

| Letter fluency score | 40.00 | 12.97 | 37.88 | 6.71 | 1 | .17 | .69 |

| Odor threshold score | 5.69 | 2.07 | 5.38 | 1.85 | 1 | .10 | .76 |

| SDOIT Score | 5.25 | 1.04 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 1 | 2.47 | .14 |

| DRS | 140.63 | 2.77 | 142.25 | 3.45 | 1 | 1.07 | .32 |

| MMSE | 27.00 | 2.73 | 26.13 | 2.75 | 1 | .41 | .53 |

P3 Latency

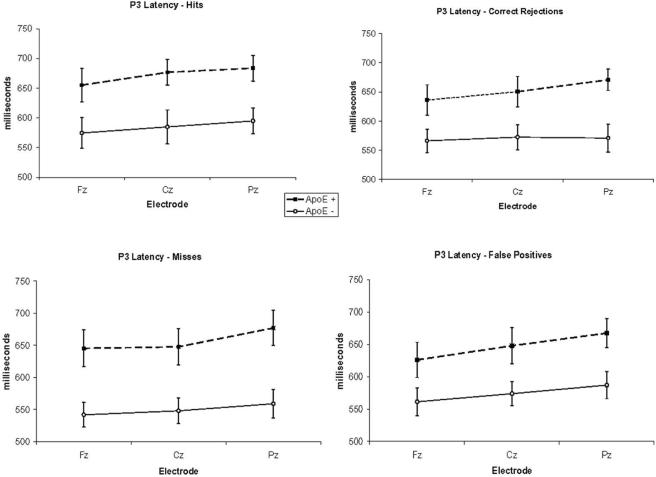

Olfactory ERP studies have focused almost exclusive on the Fz, Cz and Pz electrode sites and thus, to place the data in the context of the literature, we first conducted ANOVA on midline electrode sites (Table 1). ANOVA of P3 latency showed that latency was significantly delayed in ApoE ε4+ individuals [F(1,18) = 9.6, p < .05, eta2 = .35] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

P3 latency for ApoE ε4+ and ε4− participants.

Intra-class Correlations

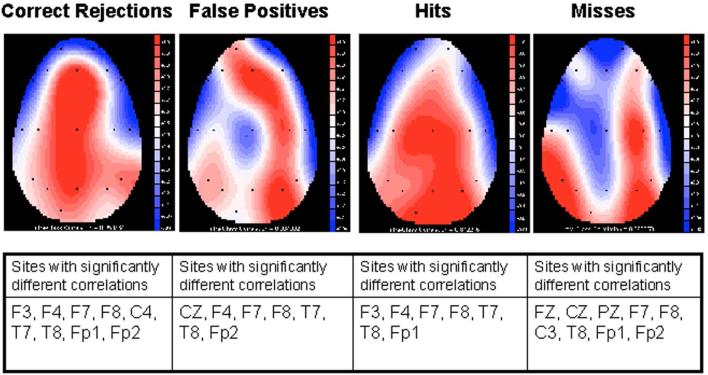

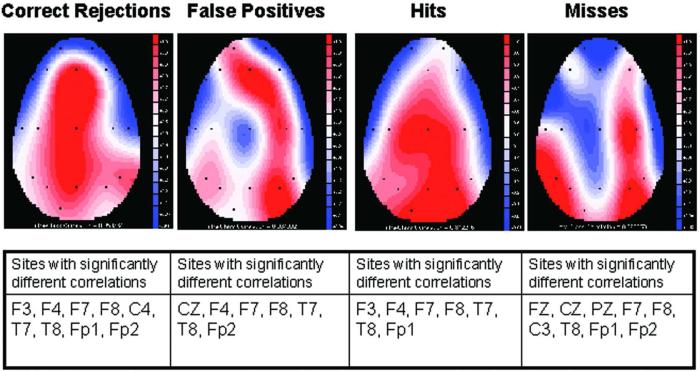

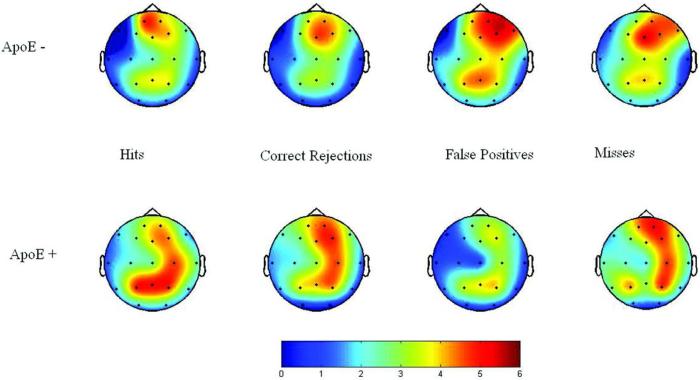

To investigate differences in activity between groups intra-class correlations of the positive area measured from 525-675 msec post stimulus from ApoE ε4+and ε4− participants were examined at each electrode sites and for each response type. The 525-675 msec post-stimulus response epoch was used in order to capture the epoch during which the P3s for the participants were generated (See Fig. 1). The intra-class correlation expresses the degree of overlap and related variability between two waveforms. The statistic is generated by comparing two ERP waveforms, taking into account both waveshape and absolute voltage values. Correlation values below .44 (p < .05) indicated statically significant differences in amplitude (See Table 3). As illustrated in Table 3, there were significant differences in activity between groups. Intra-class correlations for each of the response types are given in Figure 2, with blue indicating the largest differences between groups and red indicating greatest similarity between groups. The topographical maps in Figure 3 illustrate the group differences in P3 amplitude, with warmer colors indicating greater amplitude.

Table 3.

Intra-class correlations at the 19 electrode sites, comparing brain response in ε4+ and ε4− individuals during the four memory response types: correct rejections, false positives, hits and misses respectively.

| Electrode Site | Correct Rejections: Correlation (r) | False Positives: Correlation (r) | Hits: Correlation (r) | Misses: Correlation (r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fz | .95 | .93 | .61 | .18* |

| Cz | .94 | .25* | .89 | .26* |

| Pz | .89 | .62 | .92 | .34* |

| F3 | .28* | .54 | .17* | .50 |

| F4 | .29* | .42* | .30* | .64 |

| F7 | .00* | .17* | .01* | .08* |

| F8 | .07* | .13* | .01* | .32* |

| C3 | .58 | .50 | .65 | .41* |

| C4 | .35* | .82 | .63 | .87 |

| T7 | .29* | .30* | .18* | .56 |

| T8 | .13* | .29* | .18* | .19* |

| P3 | .73 | .66 | .75 | .80 |

| P4 | .68 | .96 | .91 | .96 |

| P7 | .60 | .71 | .72 | .98 |

| P8 | .78 | .67 | .60 | .76 |

| FP1 | .10* | .73 | .12* | .03* |

| FP2 | .01* | .06* | .47 | .11* |

| O1 | .74 | .51 | .95 | .68 |

| O2 | .80 | .71 | .95 | .75 |

Correlations that indicate significantly different responses are indicated by.

Figure 2.

Intra-Class correlations for electrode sites for the four response types for ε4+ and ε4− individuals. Blue indicates the greatest differences between groups and red the highest correlations between groups.

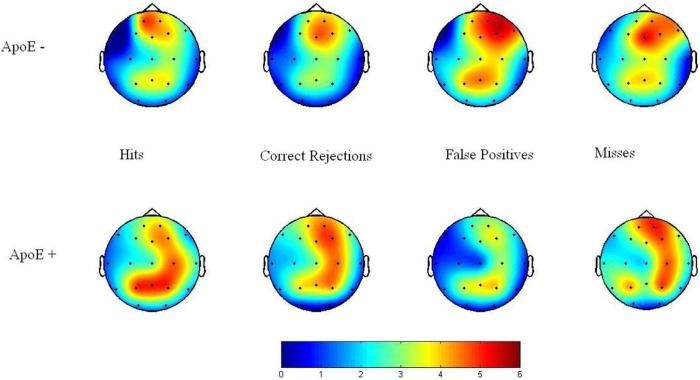

Figure 3.

P3 amplitude for the four response types for ε4+ and ε4− individuals. Warmer colors indicate greater amplitude.

Discussion

This study was designed to investigate whether EEG correlates of cross-modal odor recognition memory discriminate between ε4+ and ε4− individuals. The results support significant differences between ε4+ and ε4− individuals in P3 latency and in intra-class correlations of activity.

Psychophysical and Cognitive Functioning Tests

No significant differences were found in psychophysical and cognitive functioning test scores between ε4+ and ε4− participants, suggesting that participants had similar olfactory functioning supporting similar sensory encoding of the olfactory stimuli. Participants with anosmia or serious hyposmia were screened out using the odor threshold test, thus this result is not surprising.

P3 Latency, & Intra-Class Correlations

P3 Latency

The original hypothesis that ε4+ participants would demonstrate longer P3 latencies than ε4− participants was supported. This is the first report of longer latencies in a cross-modal odor recognition memory task. Latency differences have been observed in ERP studies using oddball tasks;75,66 however, this is the first observation that a cross-modal odor recognition memory task discriminates between ε4+and ε4− individuals. Longer P3 latencies in ε4+ individuals are consistent with the theory that ε4+ individuals demonstrate slower cognitive processing than normal older adults and are at risk for subsequently developing AD.

Amplitude & Intra-class Correlations

Figure 3 illustrates the differences in P3 amplitude between ε4+ and ε4− participants at the different electrode sites.

Intra-class correlations were employed in order to compare waveshape and voltage values at each individual electrode site between ε4+ and ε4− participants. These correlations were generated for each response type using a 525 675 milliseconds post stimulus response epoch to capture the epoch during which the P3s for the participants were generated (See Fig. 1). For correct rejection responses, ε4+ and ε4− participants showed significant differences in intra-class correlations in electrode sites over frontal (F3, F4, F7, F8, Fp1, Fp2) and temporal areas (T7, T8). This effect was also observed when evaluating hit responses (F3, F4, F7, F8, T7, T8, Fp1). The ε4+ and ε4− individuals showed significantly different intra-class correlations at a number of electrode sites for false positive responses (CZ, F4, F7, F8, T7, T8, Fp2) and misses (FZ, CZ, PZ, F7, F8, C3, T8, Fp1, Fp2), suggesting that differential activity underlies these performance errors (See Table 3 and Figure 2). These findings are consistent with the compensatory hypothesis that ε4+ individuals expend greater effort in cognitive processing in a cross-modal odor recognition memory task than ε4− individuals. This increased effort observed in ε4+ individuals requires activation of a greater area extent of neural tissue, or an increased firing rate within a given area, or a larger number of neurons recruited to perform the task. This pattern of correlations is also compatible with the hypothesis that ε4+ individuals may engage in different strategies in order to perform the task. Preliminary data from our laboratory using fMRI are also consistent with these hypotheses. 76

These findings are complemented by anatomical studies that have demonstrated that ε4+ individuals experience greater temporal atrophy than ε4− individuals.77,78 Finally, intra-class correlations lend further support to neuropsychological studies that suggest false positive responses were able to discriminate between ε4+ and ε4− individuals.52,79

Conclusion

ApoE ε4+ individuals demonstrated significantly longer P3 latency than ε4+ individuals and differential activity for all response types. Differential activity in ApoE ε4+and ε4− individuals, demonstrated by the intra-class correlation coefficients, is consistent with a compensatory hypothesis, which posits that ε4+ individuals expend greater effort in cognitive processing and therefore require greater activation of neural tissue during retrieval attempts. Finally, in accordance with previous ERP and fMRI studies involving odor familiarity, participants exhibited greater positive area in electrode sites over the right hemisphere in comparison to the left hemisphere. These findings suggest that cross-modal ERP studies of recognition memory in ApoE ε4+and ε4− individuals are a useful measure for indexing functional brain integrity, for understanding the neurocognitive changes associated with the ApoE ε4 allele, and for discriminating between brain response in ε4+ and ε4− individuals.

Table 2.

ANOVA Results Comparing P3 Latency for ApoE ε4+ and ApoE ε4− Participants

| P3 Latency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | df | F | Sig. | η p 2 |

| Allele Status (AS) | 1 | 9.59 | .01 | .35 |

| Site (S) | 2 | 17.63 | .00 | .50 |

| Response (R) | 3 | 1.18 | .32 | .06 |

| R X AS | 3 | .53 | .62 | .03 |

| S X R | 6 | .88 | .46 | .05 |

| S X R X AS | 6 | .57 | .64 | .03 |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Drs. Paul Gilbert, John Polich, Wendy Smith and Mr. Brian Lopez for expertise and assistance. Supported by the National Institute of Health grants DC02064 and AG04085 to Claire Murphy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hebert LE, et al. Alzheimer disease in the US population: Prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch. Neurol. 2003;60:1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrer LA, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype in patients with Alzheimer's disease: Implications for the risk of dementia among relatives. Ann. Neurol. 1995;38:797–808. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayeux R. Epidemiology of neurodegeneration. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;26:81–104. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.043002.094919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mortimer JA, Snowdon DA, Markesbery WR. Head circumference, education and risk of dementia: Findings from the Nun Study. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2003;25:671–679. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.5.671.14584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jellinger KA. Head injury and dementia. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2004;17:719–723. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200412000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motte J, Williams RS. Age-related changes in the density and morphology of plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in Down syndrome brain. Acta Neuropathol. 1989;77:535–546. doi: 10.1007/BF00687256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wisniewski KE, Wisniewski HM, Wen GY. Occurrence of neuropathological changes and dementia of Alzheimer's disease in Down's syndrome. Ann. Neurol. 1985;17:278–282. doi: 10.1002/ana.410170310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raber J, Huang Y, Ashford JW. ApoE genotype accounts for the vast majority of AD risk and AD pathology. Neurobiol. Aging. 2004;25:641–650. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farrer LA, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium. JAMA (J. Am. Med. Assoc.) 1997;278:1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corder EH, et al. The apolipoprotein E E4 allele and sex-specific risk of Alzheimer's disease. JAMA (J. Am. Med. Assoc.) 1995;273:373–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Namba Y, et al. Apolipoprotein E immunoreactivity in cerebral amyloid deposits and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease and kuru plaque amyloid in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain Res. 1991;541:163–166. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91092-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saunders AM, et al. Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele distributions in late-onset Alzheimer's disease and in other amyloid-forming diseases. Lancet. 1993;342:710–711. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91709-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das HK, et al. Isolation, characterization, and mapping to chromosome 19 of the human apolipoprotein E gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:6240–6247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olaisen B, Teisberg P, Gedde-Dahl T., Jr. The locus for apolipoprotein E (apoE) is linked to the complement component C3 (C3) locus on chromosome 19 in man. Hum. Genet. 1982;62:233–236. doi: 10.1007/BF00333526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poirier J, et al. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1993;342:697–699. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91705-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strittmatter WJ, et al. Apolipoprotein E: High-avidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:1977–1981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poirier J. Apolipoprotein E in animal models of CNS injury and in Alzheimer's disease. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:525–530. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tapiola T, et al. CSF tau is related to apolipoprotein E genotype in early Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1998;50:169–174. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soininen HS, Riekkinen PJ., Sr. Apolipoprotein E, memory and Alzheimer's disease. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:224–228. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feskens EJ, et al. Apolipoprotein e4 allele and cognitive decline in elderly men. BMJ. 1994;309:1202–1206. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6963.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haan MN, et al. The role of APOE epsilon4 in modulating effects of other risk factors for cognitive decline in elderly persons. JAMA (J. Am. Med. Assoc.) 1999;282:40–46. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyman BT, et al. Apolipoprotein E and cognitive change in an elderly population. Ann. Neurol. 1996;40:55–66. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonker C, et al. Association between apolipoprotein E epsilon4 and the rate of cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly individuals with and without dementia. Arch. Neurol. 1998;55:1065–1069. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.8.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yaffe K, et al. Apolipoprotein E phenotype and cognitive decline in a prospective study of elderly community women. Arch. Neurol. 1997;54:1110–1114. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550210044011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riley KP, et al. Cognitive function and apolipoprotein E in very old adults: findings from the Nun Study. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2000;55:S69–75. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.2.s69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carmelli D, et al. The joint effect of apolipoprotein E epsilon4 and MRI findings on lower-extremity function and decline in cognitive function. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2000;55:M103–109. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.2.m103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staehelin HB, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotypes and cognitive functions in healthy elderly persons. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1999;100:53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1999.tb00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henderson AS, et al. Apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4, dementia, and cognitive decline in a population sample. Lancet. 1995;346:1387–1390. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Hara R, et al. The APOE epsilon4 allele is associated with decline on delayed recall performance in community-dwelling older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1998;46:1493–1498. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Small BJ, Basun H, Backman L. Three-year changes in cognitive performance as a function of apolipoprotein E genotype: Evidence from very old adults without dementia. Psychol. Aging. 1998;13:80–87. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.13.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brayne C, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype in the prediction of cognitive decline and dementia in a prospectively studied elderly population. Dementia. 1996;7:169–174. doi: 10.1159/000106873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Helkala EL, et al. Memory functions in human subjects with different apolipoprotein E phenotypes during a 3-year population-based follow-up study. Neurosci. Lett. 1996;204:177–180. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12348-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braak H, Braak E. Staging of Alzheimer-related cortical destruction. Int. Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(Suppl 1):257–261. discussion 269-272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Price JL, et al. The distribution of tangles, plaques and related immunohistochemical markers in healthy aging and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 1991;12:295–312. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(91)90006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esiri MM, Wilcock GK. The olfactory bulbs in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1984;47:56–60. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.47.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bacon AW, et al. Very early changes in olfactory functioning due to Alzheimer's disease and the role of apolipoprotein E in olfaction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998;855:723–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murphy C, et al. Olfactory thresholds are associated with degree of dementia in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 1990;11:465–469. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(90)90014-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nordin S, Murphy C. Impaired sensory and cognitive olfactory function in questionable Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsych. 1996;10:112–119. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serby M. Olfaction and Alzheimer's disease. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 1986;10:579–86. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(86)90027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doty RL, et al. Odor identification deficit of the parkinsonism-dementia complex of Guam: Equivalence to that of Alzheimer's and idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1991;5(Suppl 2):77–80. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.5_suppl_2.77. discussion 80-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morgan CD, Nordin S, Murphy C. Odor identification as an early marker for Alzheimer's disease: Impact of lexical functioning and detection sensitivity. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1995;17:793–803. doi: 10.1080/01688639508405168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy C, Bacon A, Bondi MW, Salmon DP. Apolipoprotein E status is associated with odor identification deficits in nondemented older persons. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998;855:744–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murphy C, Nordin S, Jinich S. Very early decline in recognition memory for odors in Alzheimer's disease. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 1999;6:229–240. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schiffman SS, Graham BG, Sattely-Miller EA, Zervakis J, Welsh-Bohmer K. Taste, smell and neuropsychological performance of individuals at familial risk for Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2002;23:397–404. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bacon AW, Paulsen JS, Murphy C. A test of odor fluency in patients with Alzheimer's disease and Huntington's chorea. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1999;21:341–351. doi: 10.1076/jcen.21.3.341.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morgan CD, Murphy C. Olfactory event-related potentials in Alzheimer's disease. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2002;8:753–763. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702860039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamagishi M, et al. Increased density of olfactory receptor neurons immunoreactive for apolipoprotein E in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1998;107:421–426. doi: 10.1177/000348949810700511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Calhoun Haney R, Murphy C. Apolipoprotein epsilon4 is associated with more rapid decline in odor identification than in odor threshold or Dementia Rating Scale scores. Brain Cogn. 2005;58:178–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Craik FIM, Lockhart RS. Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. J. Verb. Learn. Verb. Behav. 1972;11:671–84. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stark CE, Squire LR. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) activity in the hippocampal region during recognition memory. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:7776–7781. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07776.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morcom AM, Rugg MD. Getting ready to remember: The neural correlates of task set during recognition memory. Neuroreport. 2002;13:149–152. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200201210-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gilbert PE, Murphy C. The effect of the ApoE epsilon4 allele on recognition memory for olfactory and visual stimuli in patients with pathologically confirmed Alzheimer's disease, probable Alzheimer's disease, and healthy elderly controls. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2004;26:779–794. doi: 10.1080/13803390490509439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nordin S, Murphy C. Odor memory in normal aging and Alzheimer's disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998;855:686–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sundermann EE, Gilbert PE, Murphy C. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 genotype and gender: Effects on memory. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2007;15:869–878. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318065415f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lehtovirta M, et al. Volumes of hippocampus, amygdala and frontal lobe in Alzheimer patients with different apolipoprotein E genotypes. Neuroscience. 1995;67:65–72. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00014-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bondi MW, et al. Episodic memory changes are associated with the APOE-epsilon 4 allele in nondemented older adults. Neurology. 1995;45:2203–2206. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.12.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morgan CD, et al. Olfactory event-related potentials: Older males demonstrate the greatest deficits. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1997;104:351–358. doi: 10.1016/s0168-5597(97)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murphy C, et al. Olfactory-evoked potentials: Assessment of young and elderly, and comparison to psychophysical threshold. Chem. Senses. 1994;19:47–56. doi: 10.1093/chemse/19.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Donchin E, Coles MG. Is the P300 component a manifestation of context updating? Behav. Brain Sci. 1988;11:357–427. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Polich J. P300 clinical utility and control of variability. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1998;15:14–33. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Geisler MW, et al. Neuropsychological performance and cognitive olfactory event-related brain potentials in young and elderly adults. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1999;21:108–126. doi: 10.1076/jcen.21.1.108.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kramer AF, Strayer DL. Assessing the development of automatic processing: An application of dual-task and event-related brain potential methodologies. Biol. Psychol. 1988;26:231–267. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(88)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wickens C, et al. Performance of concurrent tasks: A psychophysiological analysis of the reciprocity of information-processing resources. Science. 1983;221:1080–1082. doi: 10.1126/science.6879207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morgan CD, et al. Olfactory P3 in young and older adults. Psychophysiology. 1999;36:281–287. doi: 10.1017/s0048577299980265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Murphy C, et al. Olfactory event-related potentials and aging: Normative data. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2000;36:133–145. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(99)00107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wetter S, Murphy C. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 positive individuals demonstrate delayed olfactory event-related potentials. Neurobiol. Aging. 2001;22:439–447. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Suchan B, et al. Cross-modal processing in auditory and visual working memory. Neuroimage. 2006;29:853–858. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang D, et al. Cross-modal temporal order memory for auditory digits and visual locations: An fMRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2004;22:280–289. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cerf-Ducastel B, Murphy C. Neural substrates of cross-modal olfactory recognition memory: An fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2006;31:386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Murphy C, et al. Prevalence of olfactory impairment in older adults. JAMA (J. Am. Med. Assoc.) 2002;288:2307–2312. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.18.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murphy C, Nordin S, Acosta L. Odor learning, recall, and recognition memory in young and elderly adults. Neuropsychol. 1997;11:126–137. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.11.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mattis S. Dementia Rating Scale: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Semlitsch HV, et al. A solution for reliable and valid reduction of ocular artifacts, applied to the P300 ERP. Psychophysiology. 1986;23:695–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Green J, Levey AI. Event-related potential changes in groups at increased risk for Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 1999;56:1398–1403. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.11.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Murphy C, Haase L, Wang M. The ApoE ε4 risk factor for Alzheimer's Disease alters fMRI brain activation in a cross-modal odor recognition memory task. in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Geroldi C, et al. APOE-epsilon4 is associated with less frontal and more medial temporal lobe atrophy in AD. Neurology. 1999;53:1825–1832. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.8.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rosso SM, et al. Apolipoprotein E4 in the temporal variant of frontotemporal dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2002;72:820. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.6.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gilbert PE, Murphy C. Differences between recognition memory and remote memory for olfactory and visual stimuli in nondemented elderly individuals genetically at risk for Alzheimer's disease. Exp. Gerontol. 2004;39:433–41. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]