Abstract

Background

Coformulated elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (EVG/COBI/FTC/TDF; Stribild®) is a recommended integrase inhibitor-based regimen in treatment guidelines from the US Department of Health and Human Services and the British HIV Association. The purpose of this analysis was to determine the change in patient-reported symptoms over time among HIV-infected adults who switch to Stribild® versus those continuing on a protease inhibitor (PI) with FTC/TDF.

Methods

A secondary analysis was conducted on the STRATEGY-PI study (GS-US-236-0115, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01475838), a randomized, open-label, phase 3b trial of HIV-infected adults taking a PI with FTC/TDF who were randomly assigned (2:1) either to Stribild® (switch) or continuation of their existing regimen (no-switch). Logistic regressions and longitudinal modeling were conducted to evaluate the relationship of treatment with bothersome symptoms.

Results

At week 4 as compared with baseline, the switch group experienced a statistically significantly lower prevalence in five symptoms (diarrhea/loose bowels, bloating/pain/gas in stomach, pain/numbness/tingling in hands/feet, nervous/anxious, and trouble remembering). The lower prevalence of diarrhea/loose bowels, bloating/pain/gas in stomach, and pain/numbness/tingling in hands/feet observed at week 4 was maintained over time. While there were no significant differences between groups in the prevalence of sad/down/depressed and problems with sex at week 4 or week 48, longitudinal models indicated the switch group had a statistically significantly decreased prevalence in both symptoms from week 4 to week 48. As compared with the no-switch group, higher levels of satisfaction with treatment were experienced by patients in the switch group at the first follow-up visit and at week 24.

Conclusions

In this study sample, a switch from a ritonavir-boosted PI, FTC, and TDF regimen to coformulated EVG/COBI/FTC/TDF was associated with more treatment satisfaction and a reduction in the prevalence of patient-reported diarrhea/loose bowel symptoms, which was maintained over the 48-week study period.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40271-015-0137-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Little is known about how HIV patients’ symptoms change after switching to Stribild® versus continuing a regimen consisting of a protease inhibitor with emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. |

| In this study, switching to Stribild® was associated with significant, maintained improvements from baseline to 48 weeks in three patient-reported HIV symptoms: diarrhea/loose bowels, bloating/pain/gas in stomach, and pain/numbness/tingling in hands/feet. |

| Higher levels of satisfaction with treatment were experienced by patients who switched to Stribild® compared with the no-switch group at the first follow-up visit, and those treated with Stribild® also reported greater treatment satisfaction at week 24. |

Introduction

Effective combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has led to significant declines in HIV/AIDS-related morbidity and mortality. The success of cART is highly dependent on patient adherence to therapy, which may be influenced by a variety of factors, including regimen complexity and treatment tolerability [1]. Experiencing symptoms related to treatment and/or disease increases the risk for undesirable clinical outcomes, including hospitalization, lower health-related quality of life, and shortened survival [2]. Guideline-recommended cART regimens differ not only in complexity (number of prescribed pills, frequency of dosing, food requirements) [3], but also tolerability. One strategy to improve the complexity of cART is regimen simplification, a change in established effective therapy to reduce pill burden and/or dosing frequency [4], which may also improve treatment tolerability and adherence because of the unique side effect profile of each antiretroviral medication.

Switching from a multi-tablet regimen to a single-tablet regimen is one type of regimen simplification, and might be a useful option for virologically suppressed patients on a multi-tablet cART regimen. In addition to simplicity, some newer single-tablet regimens may be better tolerated by patients. Switching to a coformulated single-tablet regimen consisting of elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (EVG/COBI/FTC/TDF; Stribild®, STB) has demonstrated non-inferiority efficacy [HIV-1 ribonucleic acid (RNA) <50 copies/mL] at week 48 compared with continuation of multi-tablet ritonavir (RTV)-boosted protease inhibitor (PI), FTC, and TDF regimen in virologically suppressed adults [5]. The symptom experience of patients switching to EVG/COBI/FTC/TDF compared with the symptom experience of those who continue a multi-tablet RTV-boosted PI regimen has not been determined. This analysis describes changes in patient-reported symptoms over 48 weeks in virologically suppressed HIV-infected adults who simplified therapy to EVG/COBI/FTC/TDF versus those who remained on a multi-tablet RTV-boosted PI, FTC, and TDF regimen, as well as a comparison of patient-reported satisfaction between the two regimens.

Methods

Study Design

Details regarding the study design and patient recruitment have been previously described [5] and are summarized here. STRATEGY-PI (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01475838) was an international, open label, randomized study, which evaluated the efficacy (non-inferiority), safety, and tolerability of switching to the single-tablet regimen STB containing EVG 150 mg, COBI 150 mg, FTC 200 mg, and TDF 300 mg, from a regimen consisting of an RTV-boosted PI, FTC, and TDF (PI + RTV + FTC/TDF) in virologically suppressed HIV-1 infected subjects. Between December 12, 2011, and December 20, 2012, 433 participants were randomly assigned (2:1) and dosed; 293 switched to the simplified regimen of STB (switch group) and 140 remained on their baseline PI-containing regimen (no-switch group). After exclusions, 290 and 139 participants, respectively, were analyzed in the modified intention-to-treat population. Post-baseline study visits occurred at weeks 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48. Participants and investigators were not masked to the treatment allocation in this open-label study.

Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Demographics (gender, age, race, and ethnicity) and clinical characteristics [serious mental illness, cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) cell count, asymptomatic status, years since HIV diagnosis, years since first antiretroviral therapy use, on first antiretroviral regimen, PI used at randomization, the Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS) Index, and Fibrosis (FIB)-4 score] were collected or calculated. Serious mental illness was defined as a diagnostic history of one or more of the following conditions based on medical chart review: major depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, or other psychosis. The VACS Index was calculated to quantify the overall mortality risk associated with HIV. The VACS Index is a summary score based on age, CD4 count, HIV-1 RNA, the FIB-4 score, creatinine, and viral hepatitis C infection to predict all-cause and cause-specific mortality and other outcomes in those living with HIV infection and mortality among those without HIV infection [6]. The FIB-4 score is computed using age, platelet, aspartate and alanine transaminase values, and provides an estimate of the degree of liver fibrosis in HIV and hepatitis C virus co-infected patients [7].

At the enrollment visit, study subjects were asked to endorse the reason(s) they chose to enroll in the study. Options included (a) “Desire to simplify your current anti-HIV regimen”; (b) “I am not tolerating the current regimen well because of side effects”; (c) “I am concerned about the long-term side effects of my current anti-HIV regimen”; (d) “I am having trouble taking my current regimen on a regular basis”; and (e) “Other.”

Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs)

HIV Symptom Index (HIV-SI)

The dependent variable in this study was the HIV Symptom Index (HIV-SI). The HIV-SI is a validated patient-reported outcome (PRO) instrument that assesses the symptom burden of 20 common HIV symptoms associated with HIV treatment or disease [8]. The instrument was developed on the basis of literature review and clinical and advisory board feedback, is supported by evidence of good construct validity, and has been considered the gold standard in contemporary HIV symptom research [9]. Patients are asked about their experience with each symptom during the past 4 weeks using a 5-point Likert-type scale. Response options and scores are as follows: (0) “I don’t have this symptom”; (1) “I have this symptom and it doesn’t bother me”; (2) “I have this symptom and it bothers me a little”; (3) “I have this symptom and it bothers me”; (4) “I have this symptom and it bothers me a lot.”

The 20 symptoms comprising the HIV-SI are fatigue/loss of energy, difficulty sleeping, nervous/anxious, diarrhea/loose bowels, changes in body composition, sad/down/depressed, bloating/pain/gas in stomach, muscle aches/joint pain, problems with sex, trouble remembering, headaches, pain/numbness/tingling in hands/feet, skin problems/rash/itching, cough/trouble breathing, fever/chills/sweats, dizzy/lightheadedness, weight loss/wasting, nausea/vomiting, hair loss/changes, and loss of appetite/food taste.

Consistent with prior analyses by Edelman et al. [10], symptoms were dichotomized into a 0 (not present or no bother) or 1 (bothered 2, 3, or 4) scale for individual presentation in order to provide information about symptoms not only present but bothersome and, thus, clinically relevant to treatment decisions. In addition, the overall bothersome symptom count at baseline was generated by counting the number of individual symptoms scored as bothersome and used as a covariate in regression analyses and longitudinal modeling.

Descriptive PRO Measures

A number of PRO instruments were used to provide descriptive information and also served as covariates in regression and longitudinal analyses. The Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) from the Short Form 36 (SF-36), an instrument supported by extensive evidence of good psychometric properties in a range of therapeutic areas [11], including HIV-infected individuals [12], were used to describe health-related quality of life [13]; the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) Adherence Questionnaire [14], a validated instrument that correlates significantly with Medication Event Monitoring System caps and pharmacy data, was used to assess patient-reported adherence to their antiretroviral regimen using a linear scale (0–100 %) to indicate what proportion of medications was taken in the last 30 days; and the HIV Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (HIVTSQ), a ten-item instrument with five items assessing general treatment satisfaction and five items assessing treatment ease [15], was used and is supported by evidence of good internal consistency and reliability [16]. The status form (HIVTSQs) was used at baseline and asks about “now,” and the change form (HIVTSQc), in which items state “compared to before,” was used at week 4 and week 24. For the HIVTSQs form, the response options are anchored at 6 and 0, and for the HIVTSQc form, answers range from values of 3 to −3. The total score ranges from 0 to 60 for the status form at baseline and from −30 to 30 for the change form, with higher positive scores indicating more/improved satisfaction and higher negative scores indicating greater dissatisfaction.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Questionnaires were submitted by 96 % of enrolled patients at baseline and 80 % at week 48, the decline due in part to patients that left the study. Of the questionnaires received, there were roughly 140 items with missing values, of a total of 170,000 records (<0.1 %). As in the analyses completed for the STRATEGY-non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) trial [17], imputation rules were applied to the HIV-SI data. If multiple responses were provided for a single item, the most severe (maximum) of the responses was used (Justice A., personal communication, July 28, 2014). For single items that were left blank, but with other items completed, the missing value was imputed to “I do not have this symptom,” a score of 0 [10].

Descriptive statistics were used to describe baseline demographic and clinical characteristics and PROs. Unadjusted and adjusted analyses at week 4 and week 48 were performed to evaluate the relationship of treatment with the probability of experiencing HIV-SI items, with and without covariates. Specifically, HIV-SI symptoms were modeled as binary outcomes using a logistic regression model analysis. Each model included treatment as the independent variable and covariates which were selected from a number of potential demographic, clinical, and descriptive variables that were evaluated for multicollinearity.

Longitudinal modeling was performed using generalized mixed models to show symptom patterns over each of the seven study visits using data from the HIV-SI. The functional form of the change pattern was assessed visually from the observed prevalence in each group. Linear and quadratic patterns were tested to determine optimal fit, ultimately favoring a linear function. As with the STRATEGY-NNRTI trial [17], the decision was made to model the data from weeks 4 through 48 and include baseline as a covariate. To assess the possibility that the effect of treatment may itself vary over time, the models included an interaction between treatment and time in addition to the indicator of a simple treatment group. Continuous variables were mean centered for ease of interpretation and model fit. The fit of the derived models were compared with a simple unadjusted model that included time and treatment, along with a random intercept to account for the longitudinal nature of the data. The comparison was based on Bayesian information criterion (BIC).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were similar in the two treatment groups (Table 1). At randomization, the majority of subjects in the switch group and no-switch group were taking atazanavir [n = 123 (42 %) and n = 51 (37 %), respectively] or darunavir [n = 113 (39 %) and n = 60 (43 %), respectively]. In the switch group versus the no-switch group, participants had a mean duration of 6 versus 5 years since HIV diagnosis and 3 years since first antiretroviral therapy use, and 73 versus 75 % were asymptomatic, respectively. The majority of patients in both groups combined (86 %) reported that the reason they chose to enroll in the study was a “Desire to simplify your current anti-HIV regimen.”

Table 1.

Patient-reported baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

| Switch group (N = 293) | No-switch group (N = 140) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 250 (85.3) | 121 (86.4) | 0.76 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 41 (9.7) | 41 (8.9) | 0.99 |

| Racea, n (%) | 0.72 | ||

| White | 234 (79.9) | 113 (80.7) | |

| Non-white | 57 (19.5) | 25 (17.9) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.50 | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 42 (14.3) | 17 (12.1) | |

| Serious mental illnessb, n (%) | 28 (9.6) | 13 (9.3) | 0.93 |

| VACS Index scorec, mean (SD) | 9.2 (9.9) | 8.0 (8.5) | 0.33 |

| FIB-4 scored, mean (SD) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.4) | 0.67 |

| Asymptomatic, n (%) | 214 (73.0) | 105 (75.0) | 0.66 |

| CD4 cell count (cells per µL), mean (SD) | 604 (274.6) | 624 (269.9) | 0.25 |

| Years since HIV diagnosis, mean (SD) | 6.0 (4.8) | 5.0 (3.6) | 0.79 |

| Years since first antiretroviral therapy use, mean (SD) | 3.0 (2.8) | 3.0 (2.2) | 0.23 |

| On first antiretroviral therapy regimen at randomization, n (%) | 226 (77.1) | 116 (82.9) | 0.17 |

| Protease inhibitor at randomization, n (%) | 0.56 | ||

| Atazanavir | 123 (42.0) | 51 (36.7) | |

| Darunavir | 113 (38.6) | 60 (43.2) | |

| Lopinavir | 49 (16.7) | 23 (16.5) | |

| Fosamprenavir | 6 (2.0) | 5 (3.6) | |

| Saquinavir | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.80 |

| HIV-SI symptom counte, mean (SD) | 4 (4.5) | 4 (4.4) | 0.80 |

| SF-36 PCSf, mean (SD) | 54.5 (6.3) | 54.4 (7.2) | 0.71 |

| SF-36 MCSf, mean (SD) | 48.9 (11.6) | 49.4 (10.0) | 0.79 |

For categorical data, p value was from the CMH test (using the general association statistic). For continuous data, p value was from the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test. p value comparing protease inhibitor at randomization compared the distribution of all five drugs, and did not focus on individual drugs

CMH Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel, FIB-4 Fibrosis 4, HIV-SI HIV Symptom Index, SD standard deviation, SF-36 MCS Short Form 36 Mental Component Summary, SF-36 PCS Short Form 36 Physical Component Summary, VACS Veterans Aging Cohort Study

aTwo subjects in the switch group and two subjects in the no-switch group did not provide race data

bSerious mental illness defined as having a history of one or more of the following diagnoses based on chart review: major depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, or other major psychiatric disorders

cThe VACS Index score is a score that sums points for age, CD4 count, HIV-1 RNA, hemoglobin, platelets, aspartate and alanine transaminase, creatinine, and viral hepatitis C infection

dThe FIB-4 score is derived from age and platelet, aspartate and alanine transaminase values

eThe HIV-SI bothersome symptom count is a summation of the presence of the individual HIV-SI items and ranges from 0 to 20, with higher counts indicating more bothersome symptoms

fThe SF-36 PCS and MCS are scored from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better health

Descriptive Analysis of PRO Measures

At baseline, the prevalence rates of all 20 bothersome symptoms on the HIV-SI were similar between groups (Table 2). In the switch group, the prevalence rates of eight symptoms (nervous/anxious, diarrhea/loose bowels, changes in body composition, bloating/pain/gas in stomach, muscle aches/joint pain, problems with sex, pain/numbness/tingling in hands/feet, and fever/chills/sweats) were significantly lower at week 4 compared with baseline; at week 48, the prevalence of only half of these symptoms (diarrhea/loose bowels, changes in body composition, bloating/pain/gas in stomach, and fever/chills/sweats) remained significantly lower. In the no-switch group, the prevalence rates of three symptoms (headaches, fever/chills/sweats, and weight loss/wasting) were significantly lower at week 4 compared with baseline; at week 48, the prevalence of only one of these symptoms (headaches) remained significantly lower.

Table 2.

Frequency of HIV symptoms by study visit in the switch and no-switch groups

| Switch group baseline (%) N = 286 |

No-switch group baseline (%) N = 135 |

Switch group week 4 (%) N = 280 |

No-switch group week 4 (%) N = 124 |

Switch group week 48 (%) N = 259 |

No-switch group week 48 (%) N = 117 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue/loss of energy | 35.7 | 42.2 | 34.5 | 34.9 | 33.6 | 33.3 |

| Difficulty sleeping | 31.5 | 29.6 | 28.1 | 34.1 | 29.4 | 27.5 |

| Nervous/anxious | 30.4 | 28.9 | 22.1** | 27.1 | 26.0 | 20.8 |

| Diarrhea/loose bowels | 29.0 | 27.4 | 13.5***,^^^ | 31.0^^^ | 11.3***,^^^ | 25.8^^^ |

| Changes in body composition | 28.3 | 25.9 | 18.5*** | 24.8 | 23.4* | 20.0 |

| Sad/down/depressed | 27.6 | 23.7 | 24.6 | 26.4 | 25.3 | 25.0 |

| Bloating/pain/gas in stomach | 26.2 | 23.7 | 18.5**,^^ | 31.0^^ | 20.0* | 24.2 |

| Muscle aches/joint pain | 25.5 | 25.2 | 17.1** | 21.7 | 20.4 | 18.3 |

| Problems with sex | 25.5 | 20.0 | 20.3* | 20.2 | 20.8 | 21.7 |

| Trouble remembering | 20.6 | 25.9 | 18.9 | 24.8 | 24.9 | 24.2 |

| Headaches | 18.9 | 20.7 | 16.0 | 13.2* | 17.4 | 11.7* |

| Pain/numbness/tingling in hands/feet | 18.9 | 19.3 | 12.5**,^ | 20.9^ | 17.7 | 18.3 |

| Skin problems/rash/itching | 17.1 | 17.0 | 15.3 | 14.7 | 18.9 | 16.7 |

| Cough/trouble breathing | 15.0 | 11.1 | 13.5 | 10.9 | 11.3 | 12.5 |

| Fever/chills/sweats | 14.0 | 13.3 | 8.2** | 7.0* | 9.1* | 8.3 |

| Dizzy/lightheadedness | 11.9 | 16.3 | 13.2 | 12.4 | 10.9 | 11.7 |

| Weight loss/wasting | 11.5 | 14.1 | 10.0 | 5.4** | 9.4 | 7.5 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 11.2 | 5.9 | 7.5 | 5.4 | 6.4 | 7.5 |

| Hair loss/changes | 10.1 | 11.1 | 8.2 | 12.4 | 13.6 | 12.5 |

| Loss of appetite/food taste | 5.9 | 5.9 | 7.8 | 3.1 | 7.9 | 5.8 |

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 McNemar test within group for change from baseline

^ p < 0.05, ^^ p < 0.01, ^^^ p < 0.001 Chi square test between group differences

Satisfaction with treatment was similar between groups at baseline. At weeks 4 and 24, the mean HIVTSQc scores were positive for both groups, indicating greater satisfaction with treatment; however, the scores for the switch group were statistically significantly higher compared with the no-switch group [mean (SD) at week 4: switch group 21.5 (9.4) and no switch group 13.3 (11.8), p < 0.001; mean (SD) at week 24: switch group 23.1 (8.8) and no switch group 14.5 (12.9), p < 0.001]. SF-36 PCS scores were high at baseline for the switch and no-switch groups [mean (SD) 54.5 (6.3) vs. 54.4 (7.2), respectively, p = 0.71], while MCS scores were just below US population norms for both groups [mean (SD) 48.9 (11.6) vs. 49.4 (10.0), respectively, p = 0.79]. At week 48, the PCS and MCS mean scores were largely unchanged for the switch and no-switch groups [PCS change from baseline, mean (SD) 0.5 (5.8) vs. −0.2 (5.2), respectively, p = 0.52; MCS change from baseline, mean (SD) −0.1 (8.9) vs. −1.4 (6.8), respectively, p = 0.25], and there were again no differences observed between the switch and no-switch groups [PCS, mean (SD) 54.8 (6.8) vs. 54.3 (7.5), respectively, p = 0.69; MCS, mean (SD) 48.6 (12.1) vs. 49.0 (10.7), respectively, p = 0.79]. Patient-reported treatment adherence was ≥97 on the 100-point VAS across study visits in both treatment groups.

Associations Between HIV-SI Bothersome Symptoms and Treatment in Logistic Regression Models and Longitudinal Analyses

The association between treatment and each bothersome symptom was examined by logistic regression models and longitudinal analyses. In the final models, treatment group (switch vs. no-switch) was the independent variable and covariates included age, sex, race (white vs. non-white), baseline bothersome symptom count, VACS Index score, years since HIV diagnosis, years since first antiretroviral therapy use, baseline PI use, serious mental illness, and baseline MCS and PCS scores. Treatment adherence was not considered a covariate because nearly all participants across groups reported nearly perfect levels of adherence.

The adjusted logistic regression models show that switching to STB was associated with a lower risk of experiencing five bothersome symptoms (diarrhea/loose bowels, bloating/pain/gas in stomach, pain/numbness/tingling in hands/feet, nervous/anxious, and trouble remembering) at week 4 (see ESM Table 1 in the Electronic Supplementary Material). This association, however, was maintained only for diarrhea/loose bowels at week 48. As indicated in unadjusted and adjusted models, the no-switch group did not have a significantly lower prevalence in any symptom at week 4 or week 48 as compared with the switch group.

The prevalence of bothersome symptoms over time was evaluated using mixed-effects logistic models adjusted for the same covariates as those specified above. In all instances, the BIC of the multivariate model showed a substantial improvement in fit over the simple unadjusted model with treatment only, suggesting that bothersome symptom prevalence was associated with at least some of the predictors included in the model.

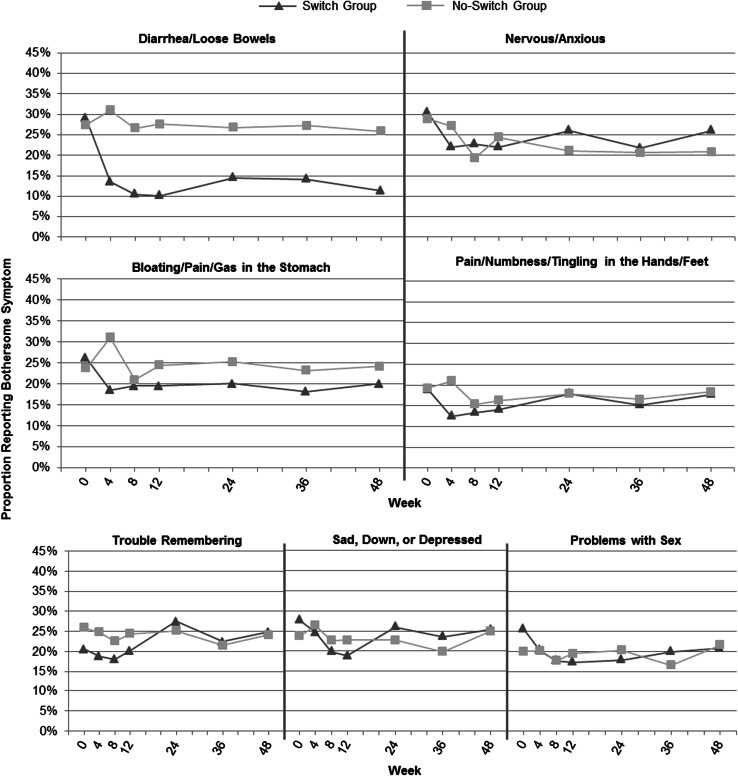

The adjusted longitudinal models revealed a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of five symptoms (diarrhea/loose bowels, bloating/pain/gas in stomach, pain/numbness/tingling in the hands/feet, sad/down/depressed, and problems with sex) between the switch and no-switch groups over time, all favoring the switch group. A complete table showing the coefficients, including findings for main effects and time by treatment interactions (the effect of time depends on whether the subject was in the switch or no-switch group), is provided in ESM Table 2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material. No covariate was significant in all symptom models; however, the presence of the bothersome symptom at baseline, the HIV-SI symptom count at baseline, and SF-36 MCS score at baseline were significant for most symptom models. Table 3 summarizes the results for symptoms with statistically significant findings in the regression and/or longitudinal analyses. Figure 1 shows the observed prevalence of each symptom from Table 3 over time by treatment group.

Table 3.

Summary of results from adjusted logistic regression analyses at weeks 4 and 48 and longitudinal analyses

| HIVI-SI bothersome symptom | Week 4 | Week 48 | Longitudinal model | Description of longitudinal findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea/loose bowels | ✓* | ✓* | ✓‡ | Switch group decreased prevalence is maintained over the study period and is significantly lower than baseline from week 4 to week 48 |

| Bloating/pain/gas in stomach | ✓* | ✓ | Switch group decreased prevalence is maintained over the study period, with no further significant changes in prevalence from week 4 to week 48 | |

| Pain/numbness/tingling in hands/feet | ✓* | ✓ | Switch group decreased prevalence is maintained over the study period, with no further significant changes in prevalence from week 4 to week 48 | |

| Nervous/anxious | ✓ | ‡ | Decreased prevalence in both groups from week 4 to week 48 | |

| Trouble remembering | ✓ | ✗ | Switch group initial decrease in prevalence is not maintained over time, with no differences in prevalence observed between groups from week 4 to week 48 | |

| Sad/down/depressed | ✓ | Switch group decreased prevalence from week 4 to week 48 | ||

| Problems with sex | ✓ | Switch group decreased prevalence from week 4 to week 48 |

HIV-SI HIV Symptom Index

✓ Statistically significant reduction for the switch group, ‡ statistically significant effect for time, ✗ statistically significant time-by-treatment interaction, * also significant in unadjusted model

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of significant HIV-SI symptoms over time by treatment group. HIV-SI HIV Symptom Index

With respect to diarrhea/loose bowels, the decreased prevalence in the switch group is maintained over the study period and is significantly lower than baseline from week 4 to week 48. With regard to bloating/pain/gas in stomach and pain/numbness/tingling in hands/feet, the decreased prevalence observed in the switch group was maintained over the study period, and no further significant changes in prevalence from week 4 to week 48 were observed. For nervous/anxious, there is initially a significant decrease in prevalence for the switch group; however, the difference is not maintained over time because both groups decrease in prevalence from week 4 to 48. For trouble remembering, the switch group’s initial decrease in prevalence was not maintained over time, and no differences in prevalence were observed between the two groups from week 4 to week 48. Finally, for both sad/down/depressed and problems with sex, there were no significant differences between groups in the prevalence of either symptom at week 4 or week 48; however, the longitudinal models revealed that compared with the no-switch group, the switch group had a statistically significant decreased prevalence from week 4 to week 48.

Discussion

This study was the first prospective randomized HIV switch trial to use the HIV-SI to assess the symptom experience of patients switching from an RTV-boosted PI to STB. The results indicate that switching to STB was associated with more treatment satisfaction, improvements in a number of patient-reported HIV symptoms that were maintained over 48 weeks, and no differences or changes in health-related quality of life.

Results of the descriptive analyses showed that diarrhea/loose bowels, bloating/pain/gas in stomach, and pain/numbness/tingling in hands and feet were statistically significantly less prevalent for the switch group at week 4. Adjusted logistic regression results were similar, with the addition of lower prevalence for nervous/anxious and trouble remembering. Of these affected symptoms, the lower prevalence of diarrhea/loose bowels for the switch compared with the no-switch group was maintained over the study period from week 4 to week 48. This was the only symptom with this finding—both a maintained advantage over the no-switch group and a significantly lower experience in prevalence throughout measurement periods as compared with baseline.

Drug-induced gastrointestinal (GI) side effects like diarrhea or loose stool, most commonly associated with the use of PIs like RTV, is a nuisance complication of HIV therapy [18]. The mechanisms for PI-associated GI dysfunction include increased calcium-dependent chloride conductance, cellular apoptosis and necrosis, and decreased proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells [19]. The findings from the present study, a prominent reduction in GI symptoms—primarily diarrhea/loose bowels, but also bloating/pain/gas in stomach—are consistent with previous studies of GI symptom prevalence in patients treated with a PI [20, 21]. For example, Lalanne et al. [21] found the rates of nausea (27 vs. 13 %, p = 0.024), diarrhea (40 vs. 25 %, p = 0.042), and abdominal pain or bloating (40 vs. 13 %, p = 0.001) were greater in PI- than non-PI-treated patients.

While it was clear that the prevalence of diarrhea/loose bowels was consistently lower among patients switching to STB, there were many symptoms that had similar patterns of prevalence across the two groups and also remained unchanged from baseline. In adjusted models, prevalence rates were essentially parallel over time for fatigue, changes in body, muscle aches/joint pain, skin problems/rash/itching, weight loss/wasting, nausea, and hair loss. The importance of the statistically significant associations found among multiple covariates with these bothersome symptoms (e.g., race, baseline VACS Index, years since HIV diagnosis, and years since first antiretroviral therapy) warrants further investigation and could inform clinicians which patients are more susceptible to certain symptoms.

A strength of the present study is the use of PRO tools, which can provide insight into patient-reported symptoms that may be underreported by clinicians [2]. Additionally, the use of longitudinal modeling allows for a greater understanding of the prevalence of HIV symptoms over time after switching antiretroviral therapy. A limitation of this study is generalizability. The majority of the study population was male and white, and findings, therefore, may not be applicable to women and patients of non-white race. Further, study results are more generalizable to a virologically suppressed patient population than a treatment-naïve patient population because inclusion criteria stipulated that all patients have viral loads at baseline that were undetectable on therapy. Another limitation of our methodology is the use of imputation for missing items and acceptance of the most severe (maximum) response when multiple responses were provided for a single item. It is possible these methods could result in an inaccurate reflection of the true patient experience. Finally, it is possible that given the open-label design, study findings may be confounded by knowledge of treatment assignment. It is possible that patients in the no-switch group were more aware of their symptoms.

Research has shown that switching virologically suppressed patients to STB from an NNRTI + FTC/TDF was associated with a reduced prevalence in HIV symptoms as early as 4 weeks after the switch [17]. This study demonstrated that switching patients to STB from an RTV-boosted PI + FTC/TDF regimen was associated with reduced prevalence in five HIV symptoms (diarrhea/loose bowels, bloating/pain/gas in stomach, pain/numbness/tingling in hands/feet, nervous/anxious, and trouble remembering) after 4 weeks, with a sustained decrease in diarrhea/loose bowels over 48 weeks. These benefits are important because PI-associated GI side effects may eventually lead to decreased quality of life and treatment interruption [18].

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Gathe contributed to the acquisition of the data and manuscript preparation. Dr. Arribas contributed to the acquisition of the data and manuscript preparation. Dr. Van Lunzen contributed to the acquisition of the data and manuscript preparation. Dr. Garner contributed to the acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation. Dr. Speck contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and manuscript preparation. Dr. Bender contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and manuscript preparation. Dr. Shreay contributed to the acquisition of the data and manuscript preparation. Dr. Nguyen contributed to the acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation, and is the guarantor of this work. We would like to thank David Budd and David Piontkowsky for their critical review of this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Potential conflicts of interest and sources of funding

Dr. Gathe has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Drs. Garner, Shreay, and Nguyen are employees of Gilead Sciences and hold stock options in the company. Dr. Arribas has received consulting fees and speaker payments from ViiV, Tibotec, Janssen, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Merck Sharp and Dohme. Dr. Van Lunzen has received consulting fees and speaker payments from Gilead. Drs. Speck and Bender are employees of Evidera, contract recipients for the project.

This study was funded by Gilead Sciences. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was reviewed and approved by central or site-specific institutional review boards or ethics committees covering all participating sites. All participants provided written informed consent.

References

- 1.Al-Dakkak I, Patel S, McCann E, Gadkari A, Prajapati G, Maiese EM. The impact of specific HIV treatment-related adverse events on adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Care. 2013;25(4):400–414. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.712667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edelman EJ, Gordon K, Justice AC. Patient and provider-reported symptoms in the post-cART era. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(4):853–861. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9706-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metz KR, Fish DN, Hosokawa PW, Hirsch JD, Libby AM. Patient-level medication regimen complexity in patients with HIV. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(9):1129–1137. doi: 10.1177/1060028014539642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. April 8 2015. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf. Accessed 13 May 2015.

- 5.Arribas JR, Pialoux G, Gathe J, Di Perri G, Reynes J, Tebas P, et al. Simplification to coformulated elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir versus continuation of ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor with emtricitabine and tenofovir in adults with virologically suppressed HIV (STRATEGY-PI): 48 week results of a randomised, open-label, phase 3b, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(7):581–589. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70782-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Justice AC, Modur SP, Tate JP, Althoff KN, Jacobson LP, Gebo KA, et al. Predictive accuracy of the Veterans Aging Cohort Study index for mortality with HIV infection: a North American cross cohort analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(2):149–163. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827df36c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43(6):1317–1325. doi: 10.1002/hep.21178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Justice AC, Holmes W, Gifford AL, Rabeneck L, Zackin R, Sinclair G, et al. Development and validation of a self-completed HIV symptom index. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(Suppl 1):S77–S90. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simpson KN, Hanson KA, Harding G, Haider S, Tawadrous M, Khachatryan A, et al. Patient reported outcome instruments used in clinical trials of HIV-infected adults on NNRTI-based therapy: a 10-year review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:164. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edelman EJ, Gordon K, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Justice AC, Vacs Project T Patient-reported symptoms on the antiretroviral regimen efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(6):312–319. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, O’Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305(6846):160–164. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsiung PC, Fang CT, Chang YY, Chen MY, Wang JD. Comparison of WHOQOL-bREF and SF-36 in patients with HIV infection. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(1):141–150. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-6252-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buscher A, Hartman C, Kallen MA, Giordano TP. Validity of self-report measures in assessing antiretroviral adherence of newly diagnosed, HAART-naive, HIV patients. HIV Clin Trials. 2011;12(5):244–254. doi: 10.1310/hct1205-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woodcock A, Bradley C. Validation of the HIV Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (HIVTSQ) Qual Life Res. 2001;10(6):517–531. doi: 10.1023/A:1013050904635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woodcock A, Bradley C. Validation of the revised 10-item HIV Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire status version and new change version. Value Health. 2006;9(5):320–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mills A, Garner W, Pozniak A, Berenguer J, Speck RM, Bender R, Nguyen T. Patient-reported symptoms over 48 weeks in a randomized, open-label, phase IIIb non-inferiority trial of adults with HIV switching to co-formulated elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir DF versus continuation of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor with emtricitabine and tenofovir DF. Patient. 2015 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Prosperi MC, Fabbiani M, Fanti I, Zaccarelli M, Colafigli M, Mondi A, et al. Predictors of first-line antiretroviral therapy discontinuation due to drug-related adverse events in HIV-infected patients: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:296. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bode H, Lenzner L, Kraemer OH, Kroesen AJ, Bendfeldt K, Schulzke JD, et al. The HIV protease inhibitors saquinavir, ritonavir, and nelfinavir induce apoptosis and decrease barrier function in human intestinal epithelial cells. Antivir Ther. 2005;10(5):645–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill A, Balkin A. Risk factors for gastrointestinal adverse events in HIV treated and untreated patients. AIDS Rev. 2009;11(1):30–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lalanne C, Armstrong AR, Herrmann S, Le Coeur S, Carrieri P, Chassany O, et al. Psychometric assessment of health-related quality of life and symptom experience in HIV patients treated with antiretroviral therapy. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(6):1407–1418. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0880-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.