Abstract

Blockade of group III–IV muscle afferents by intrathecal injection of the μ-opioid agonist fentanyl (IF) in humans has been variously reported to depress exercise hyperpnea in some studies but not others. A key unanswered question is whether such an effect is transient or persists in the steady state. Here we show that in healthy subjects undergoing constant-load cycling exercise IF significantly slows the transient exercise ventilatory kinetics but has no discernible effect on the ventilatory response when exercise is sufficiently prolonged. Thus, the ventilatory response to group III–IV muscle afferents input in healthy subjects is not a simple reflex but acts like a high-pass filter with maximum sensitivity during early-phase exercise and is reset in the late phase. In patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) IF causes sustained CO2 retention not only during exercise but also in the resting state, where muscle afferents feedback is minimal. In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), IF also elicits sustained decreases in the exercise ventilatory response but with little or no resultant CO2 retention due to concomitant decreases in physiological VD/VT (dead space-to-ventilation ratio). These results support the proposition that optimal long-term regulation of exercise hyperpnea in health and in disease is determined centrally by the respiratory controller through the continuing adaptation of an internal model which dynamically tracks the metabolic CO2 load and the ventilatory inefficiency [1/(1− VD/VT)] that must be overcome for the maintenance of arterial PCO2 homeostasis, rather than being reflexively driven by group III–IV muscle afferents feedback per se.

1. Introduction

Since the work of Dejours (1964), Founding Editor of this Journal, it has been well established that the ventilatory response to constant-load mild-to-moderate exercise in healthy subjects starting from rest or from a lower work rate comprises three distinct phases: an occasional rapid (phase I) increase in total ventilation (V̇E) at exercise onset, followed by a transient (phase II) further increase in V̇E towards a final steady state (phase III) (Fig. 1A). Although many neural or humoral inputs have been implicated to play a role in phase I/II development of exercise hyperpnea, none of them has so far unequivocally proven obligatory for phase III (Poon and Tin, 2013; Poon et al., 2007). The crux of the issue is that a fast input component for the V̇E response [presumably arising from central command (Paterson, 2014) or afferent feedback from exercising muscles (Duffin, 2014)] that peaks early during exercise may not necessarily persist throughout exercise as generally presumed (Fig. 1A). Instead, it is possible for such an input to exert its influence on V̇E only transiently during phase I/II exercise but not phase III, with the steady-state response to the fast input component being reset to the baseline like a neural differentiator or high-pass filter (Poon and Young, 2006; Tin and Poon, 2014) (Fig. 1B). The plethora of postulated neurohumoral inputs which have proved to play a role in the development of exercise hyperpnea in phase I/II but not its maintenance in phase III raises the distinct possibility that the control of V̇E is not necessarily a Sherringtonian simple reflex driven by feedback/feedforward stimuli as generally presumed. On the contrary, increasing evidence indicates that long-term regulation of V̇E in phase III exercise may be governed by an ‘internal model’ adapted by the respiratory controller during phase I/II exercise to dynamically track the metabolic CO2 production (V̇CO2) in order to determine the optimal respiratory neural output necessary to eliminate CO2 in an energetically cost-effective manner in the long run (Poon and Tin, 2013; Poon et al., 2015; Poon et al., 2007).

Fig. 1.

Dejours’ three-phase exercise ventilatory kinetics framework. A. A fast input component for the ventilatory response that peaks at exercise onset (phase I) or during the transient phase (phase II) is generally presumed to persist throughout steady-state (phase III) exercise, recovering only at exercise offset (Dejours, 1964; Duffin, 2014). B. Alternatively, a fast input component may elicit a response only during phase I or phase II but the steady-state response may be reset to the baseline in phase III and may remain unresponsive to the static input until the exercise intensity is further increased or decreased. In this case the influence of the fast input component on the ventilatory response acts like a neural differentiator or high-pass filter (Poon and Young, 2006; Tin and Poon, 2014) instead of a simple reflex.

The need to distinguish phase I/II exercise V̇E response from phase III is underscored by the recent suggestion that exercise hyperpnea in healthy subjects was depressed after partial blockade of group III–IV muscle afferents with intrathecal injection of the μ-opioid agonist fentanyl (IF) (Amann et al., 2010, 2011; Dempsey et al., 2014), whereas other studies using a similar IF approach concluded otherwise (Olson et al., 2014; Poon and Tin, 2013). In addition, IF was reported to result in a significant increase in arterial PCO2 (PaCO2) during exercise in patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) (Olson et al., 2014) but not those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Gagnon et al., 2012). Here, we show that these seemingly discrepant ventilatory effects of IF—when reconciled under Dejours’ three-phase exercise ventilatory kinetics framework—do not support a role for group III–IV muscle afferents in mediating the steady-state exercise hyperpnea response in healthy subjects and patients with CHF or COPD besides speeding up the transient ventilatory kinetics during early-phase exercise. Our results confirmed that the ventilatory response to group III–IV muscle afferents feedback in humans indeed acts like a high-pass filter (Fig. 1B), and that the control of V̇E in the steady state is mechanistically coupled to both V̇CO2 and theVD/VT (dead space to tidal volume ratio) that adds to the burden of eliminating V̇CO2, as suggested by (Poon and Tin, 2013; Poon et al., 2015). These findings lend support for the internal model hypothesis for the optimal long-term control of V̇E at rest and during steady-state exercise in health and in disease (Poon and Tin, 2013; Poon et al., 2015; Poon et al., 2007).

2. Methods

Protocols for cardiopulmonary exercise testing and experimental methods for μ-opioid-sensitive muscle afferent blockade with intrathecal injection of fentanyl (IF) or placebo at the lumbar (L3–L4) level in healthy subjects and patients with CHF or COPD performing cycling exercise are as described in previous studies (Amann et al., 2010, 2011; Dempsey et al., 2014; Gagnon et al., 2012; Olson et al., 2014) (Table 1). Original reported data from these studies were reanalyzed de novo under Dejours’ framework.

Table 1.

Summary of reported data being reanalyzed in regard to the ventilatory effects of intrathecal fentanyl on exercise hyperpnea in healthy subjects and patients with COPD and heart failure

| Data being reanalyzed | Subjects | n | Exercise test | Exercise intensity | Exercise duration | Fentanyl dosage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amann et al. (2010) | Healthy1 | 7 | Incremental | Mild to 80% peak | 3–8 min | 50 μg |

| Dempsey et al. (2014) | Healthy1 | 7 | Incremental | Mild to 80% peak | 3–8 min | 50 μg |

| Amann et al. (2011) | Healthy1 | 7 | Constant-load | 80% peak power | 9 min | 25 μg |

| Olson et al. (2014) | Healthy2 | 9 | Constant-load | 65% peak power | 5 min | 50 μg |

| Olson et al. (2014) | CHF3 | 9 | Constant-load | 65% peak power | 5 min | 50 μg |

| Gagnon et al. (2012) | COPD4 | 8 | Constant-load | 80% peak power | 7–10 min | 25 μg |

Healthy subjects are:

young male cyclists (ages ~24 yrs);

elderly male/female subjects age-matched to the CHF patients (ages ~63 yrs).

CHF subjects (ages ~60 yrs, males/females) were classified as having New York Heart Association Class I–III heart failure.

COPD patients (ages ~66 yrs) were classified as having Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage II–III COPD.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Effect of IF on exercise ventilatory kinetics in healthy subjects

3.1.1. Mild-to-moderate exercise

In (Amann et al., 2010), subjects pre-treated with IF or placebo performed incremental cycling exercise at mild-to-moderate intensities of 50, 100, and 150 W for 3 min each, followed by > 4 min of heavy exercise at 325 ± 19 W. During all but the lowest work rate (50 W) with IF, V̇E and V̇E/V̇CO2 (ventilatory equivalent for CO2) were significantly attenuated compared with placebo [Fig. 2 in (Amann et al., 2010)]. Amann et al. (2010) interpreted these data to mean that group III–IV muscle afferents contributed to the normal steady-state ventilatory response to moderate exercise in humans. However, analysis of similar data for prolonged heavy exercise in healthy subjects revealed that IF attenuated only the early-phase (< 3 min) but not late-phase (> 7 min) nonsteady exercise V̇E response, suggesting that group III–IV muscle afferents likely contributed mainly to the transient development but not steady-state maintenance of the exercise V̇E response in healthy subjects (Poon and Tin, 2013).

Subsequently, Dempsey et al. (2014) revisited the study of (Amann et al., 2010) by concatenating the 3-min incremental exercise data to highlight the frank persistence of the decreases in V̇E and elevation of end-tidal PCO2 (PETCO2) with IF throughout the entire exercise duration (Fig. S1, Supplementary Data). Based on this rerendering, Dempsey et al. (2014) reasserted that group III–IV muscle afferents were required for a normal steady-state exercise hyperpnea in humans. In contrast, an independent study (Olson et al., 2014) found that IF had no discernible effects on the V̇E response to 5-min constant-load submaximal cycling exercise or corresponding PaCO2 at end-exercise in healthy subjects (Fig. S2, Supplementary Data).

The discrepancy in the reported effects of IF on the exercise V̇E response in healthy subjects is puzzling. Olson et al. (2014) speculated that such discrepancy might be ascribable to extraneous factors such as differences in age of participants, fitness of participants, specificity of training status and exercise protocol employed. However, it is not clear how differences in age, fitness and training status between these two subject groups may contribute to the differing outcomes. If anything, older subjects who are unfit and untrained for exercise are likely to be more vulnerable to IF treatment than younger subjects, rather than the other way around. On the contrary, Olson et al. (2014) observed that the results of (Amann et al., 2010) for young healthy trained cyclists appeared to resemble similar results they reported in a group of CHF patients (Olson et al., 2014), even though the latter group was much older and physically unfit/untrained and in poor health compared to the subject population in (Amann et al., 2010).

To explore whether differences in exercise protocols could contribute to the divergent results in these studies, we replotted the data of (Olson et al., 2014) in accordance with Dejours’ three-phase exercise ventilatory kinetics framework (Fig. 2). Olson et al. (2014) reported that IF had no discernible effect on V̇E compared with placebo at the 300 sec (5 min) time point of constant-load submaximal cycling exercise in healthy subjects. On the other hand, detailed statistical analysis of the exercise ventilatory kinetics data led these authors to conclude that “…our healthy control participants had a slowed ventilatory kinetic response [under IF] during the exercise protocol, demonstrating a significant reduction in V̇E at the 150 s time point….” This conclusion of a transient reduction in V̇E is consistent with the data of (Amann et al., 2010), where the duration of exercise was cut short at 180 sec (3 min) for each work rate increment such that phase III exercise hyperpnea never fully developed under IF due to the slowed exercise ventilatory kinetics in phase II (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Schematic summary of the data from (Olson et al., 2014) and (Amann et al., 2010) showing time-dependent ventilatory response to constant-load exercise starting from rest (or from a lower work rate) in healthy subjects after intrathecal injection of fentanyl or placebo. Transient (phase II) development of the ventilatory response towards steady state (phase III) is slowed by fentanyl. The exercise protocol of (Olson et al., 2014) allows for phase III to be attained in 5 min under both fentanyl and placebo conditions, whereas the exercise protocol of (Amann et al., 2010) is cut short at 3 min before the ventilatory response under fentanyl reaches steady state. Possible abrupt increases of the ventilatory response at exercise onset (phase I, not shown) in some subjects are not included in the data of (Amann et al., 2010; Olson et al., 2014).

Importantly, the finding by Olson et al. (2014) of a slowed ventilatory kinetic response for healthy subjects under IF was based on a rigorous statistical analysis (ANOVA with repeated measures) applied to all the data points. Although Bonferroni post hoc analyses of individual data points identified a reduction in V̇E to be statistically significant for IF vs. placebo only at the 150 sec time point but not 180 sec (Olson et al., 2014), the reported data clearly indicated a trend of reduced V̇E under IF throughout the phase II period (Fig. S2, Supplementary Data) suggesting that the failure to reach statistical significance at the 180 sec time point was likely a type II statistical error due to the relatively small sample size (n = 9) in the study. Such type II error is also apparent in the data of (Amann et al., 2010), where the reduction in V̇E under IF failed to reach statistical significance (n = 7) after the first 3 min (180 sec) of exercise at 50 W, becoming significant only upon continued exercise at higher work rates [see Fig. 2 in (Amann et al., 2010)]. In both cases (Amann et al., 2010; Olson et al., 2014) the V̇E response after 3 min of constant-load moderate exercise under IF clearly remained very much in the thick of the transient phase II kinetics rather than attaining a true steady state, consistent with the slowed exercise ventilatory kinetic response reported by Olson et al. (2014).

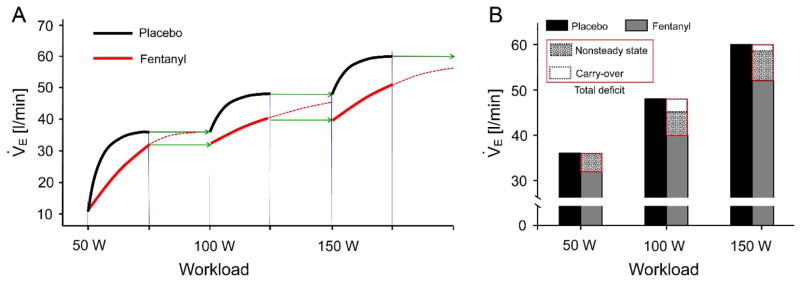

To investigate whether a similar analysis was applicable to the rerendered data in Fig. S1 (Supplementary Data) as depicted in (Dempsey et al., 2014), we retraced the Dejours plot for the first three successive exercise levels (50, 100, 150 W) in the 3-min incremental exercise protocol of (Amann et al., 2010). As shown in Fig. 3A, throughout each of the 3-min exercise levels V̇E remained nonsteady under IF, never settling into a phase III plateau even though the cumulative duration of the incremental exercise protocol lasted > 9 min. This is because the increase in work rate every 3 min reset the exercise ventilatory kinetics towards a higher and higher steady-state V̇E level, a moving target which was never attained within the 3-min period for each work rate. Such transient ventilatory deficits under IF accumulated after each work-rate increment, resulting in an even greater transient reduction in V̇E at the 100 W and 150 W exercise levels than the 50 W level (Fig. 3B). This cumulative transient ventilatory reduction due to the nonsteady incremental exercise protocol of (Amann et al., 2010) explains why the reduction in V̇E under IF was found by these authors to be significant at the 100 W and 150 W exercise levels but not at the 50 W level. It follows that the apparent persistence of the hypoventilatory response under IF in the rerendered data in Fig. S1 (Supplementary Data) as depicted in (Dempsey et al., 2014) is again ascribable to a slowed ventilatory kinetics in phase II rather than indicating a true reduction in the normal steady-state exercise hyperpnea in phase III as suggested in (Dempsey et al., 2014).

Fig. 3.

Transient ventilatory deficits caused by intrathecal fentanyl accumulate rather than settle during nonsteady incremental exercise. A. Schematic summary of the delayed ventilatory kinetics with intrathecal fentanyl that is inherent in the nonsteady incremental exercise data from (Amann et al., 2010) but is omitted in the rerendering by (Dempsey et al., 2014). Bold lines indicate time-dependent V̇E response during incremental exercise with intrathecal fentanyl (red) or placebo (black) at increasing work rates of 50, 100 and 150 W of 3 min each. Green arrows indicate theoretical extension of the exercise duration for another 3 min at each work rate, which would have allowed V̇E to attain steady state with fentanyl. Broken red lines indicate projected continuing time-dependent V̇E response with fentanyl beyond the 3-min duration for each work rate. Note that carry-over of the ventilatory deficits in successive 3-min work rates results in accumulation rather than settling of the deficits. B. Bar graphs showing total ventilatory deficit induced transiently by fentanyl with theoretical breakdown into nonsteady-state component and carry-over component at each work rate. The nonsteady-state component of the deficit with fentanyl is assumed to be the same (relative to the response with placebo) at each work rate.

3.1.2 Heavy exercise

The ventilatory effects of IF during heavy exercise are more complex, because steady-state V̇E response takes longer than 3–5 min to achieve in this case and may not be attained at all before the subject is exhausted (Riley and Cooper, 2002; Whipp and Wasserman, 1972). Nevertheless, any transient influence of IF on ventilatory kinetics during early-phase heavy exercise should gradually wash out and eventually vanish over time even though V̇E, V̇E/V̇CO2 and PaCO2 may remain nonsteady when exercise is terminated out of subject exhaustion. This prediction based on an extension of the Dejours framework to heavy exercise has been demonstrated by (Poon and Tin, 2013), who showed that the initial hypoventilatory effects of IF in young healthy subjects during heavy exercise did not persist as previously thought (Amann et al., 2011) but were completely nullified after ~7 min of constant-load heavy exercise (Fig. S3, Supplementary Data). In the present study, similar time-dependent effects are also evident in the rerendered data in Fig. S1 (Supplementary Data) at the heaviest work rate (327 ± 16 W), where the early-phase responses in V̇E/V̇CO2 and PaCO2 with IF are seen to gradually approach corresponding control values (with placebo) as exercise was prolonged beyond 3 min, even though the ventilatory responses with IF or placebo both remained nonsteady at the end of exercise (Fig. S1, Supplementary Data). This lack of persistence of the effects of IF on the ventilatory response during heavy exercise in young healthy subjects is also tacitly acknowledged in (Dempsey et al., 2014), which states that “As exercise intensity increased and/or exercise duration at high intensity was prolonged, the relative effects of [muscle] afferent blockade on the hyperventilatory, cardioaccelerator and MAP [(mean arterial pressure)] responses were clearly diminished…… we are unable to attribute [any residual differences in V̇E and Pa CO2 with IF vs. placebo] at the heaviest intensity solely to the effects of muscle afferent feedback and its sequelae”. Hence, a consensus is emerging that IF may indeed slow the early-phase exercise ventilatory kinetics but has no lasting effects on the V̇E response in young healthy subjects during prolonged heavy exercise, as originally suggested by (Poon and Tin, 2013).

3.1.3 Roles of group III–IV muscle afferents in phase I/II vs. phase III exercise hyperpnea

The foregoing analysis under Dejours’ framework confirms that group III–IV muscle afferents represent a new class of priming inputs (such as carotid chemoafferent input) which serve mainly to speed up early-phase exercise ventilatory kinetics but are inconsequential for late-phase exercise V̇E response, in accord with (Poon and Tin, 2013). For mild-to-moderate exercise, steady-state exercise hyperpnea cannot be reliably discerned under IF by using an incremental exercise protocol in which each work rate is limited to a duration of only 3 min, regardless of whether the data are analyzed separately for each work rate (Amann et al., 2010) or collectively over the entire incremental exercise duration (Dempsey et al., 2014). In both cases, a 3-min incremental exercise protocol could only reveal the slowed V̇E kinetics under IF during phase II (Amann et al., 2010; Dempsey et al., 2014) but not IF’s lack of effect on steady-state exercise hyperpnea in phase III (Olson et al., 2014). For heavy exercise where a phase III ventilatory plateau of the Dejours plot is not reached before exercise is terminated due to exhaustion, current consensus is that the early hypoventilatory effect of IF in young healthy subjects gradually declines as exercise duration is prolonged (Dempsey et al., 2014), vanishing after ~7 min of constant-load heavy exercise (Poon and Tin, 2013).

These results suggest that group III–IV muscle afferents are not required for a normal steady-state exercise hyperpnea in healthy human subjects regardless of the exercise intensity or the age, physical fitness and training status of the subjects. On the contrary, the ventilatory response to group III–IV muscle afferents input in healthy subjects appears to act like a high-pass filter (Fig. 1B) instead of a simple reflex (Fig. 1A). Similar high-pass filter characteristics with resetting of the steady-state response to the baseline have been previously demonstrated for the respiratory responses to carotid chemoreafferent input (Poon et al., 2000; Young et al., 2003) and vagal lung volume-related afferent input (MacDonald et al., 2009; Poon et al., 2000; Siniaia et al., 2000). The neural correlates of some of these respiratory high-pass filters have been identified recently (Poon and Song, 2014; Song et al., 2015). Further, IF exerted the greatest effect at the height of phase II exercise hyperpnea rather than phase I (Fig. 2) indicating that the ventilatory response to group III–IV muscle afferents input exhibits compound high-pass (differentiator) and low-pass filter (integrator) characteristics. Therefore, the fast input component for the phase I V̇E response likely arises from feedforward central command (Paterson, 2014) rather than muscle afferents feedback (Duffin, 2014). However, as noted previously such a fast input component is present only in some individuals but is not evident in the general population (Duffin, 2014) indicating that it is not obligatory for exercise hyperpnea especially in phase III. Indeed, in their seminal work Krogh and Lindhard (1913) exercised an abundance of caution in emphasizing that such a fast input component for V̇E was reproducible only “at the beginning of heavy work, especially in persons trained to sudden and violent exertion” and was pertinent only “during the initial stages of muscular work”.

In addition to group III–IV muscle afferents feedback and feedforward central command, other factors (such as carotid chemoafferent feedback) may also contribute to speeding up phase I/II ventilatory kinetics but are inconsequential for phase III exercise hyperpnea (Lugliani et al., 1971; Wasserman et al., 1975). We suggest that these feedforward and feedback exercise signals provide the necessary priming inputs for the respiratory controller to dynamically adapt an internal model of the increased metabolic CO2 load, a process which takes place mainly during the transient phase I/II development of exercise hyperpnea (Poon et al., 2007). Such an internal model [for reviews see (Poon and Merfeld, 2005; Tin and Poon, 2005)], once fully adapted by the controller, would eventually sustain the steady-state V̇E response in phase III independently of the priming inputs. Consequently, all the feedforward and feedback exercise signals which contribute to the early-phase exercise hyperpnea appear to be ‘filtered out’ or ‘reset’ or ‘buffered’ in the late phase as further training of the internal model by these priming inputs is no longer necessary until the exercise intensity is further increased or decreased. In unusual circumstances such as patients with congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (Gozal et al., 1996), muscle afferents feedback (and possibly also feedforward central command) provide the only priming inputs for the controller to adapt such an internal model during phase I/II exercise (Poon et al., 2007).

3.2 Ventilatory effects of IF in CHF patients at rest and during exercise

Patients with CHF maintain remarkably stable PaCO2 at rest and during exercise with a paradoxical increase in V̇E/V̇CO2 in compensation for the increase in physiological VD/VT due to the disease (Wasserman et al., 1997). A prevailing hypothesis ascribed the augmented steady-state V̇E/V̇CO2in these patients to increased feedback via group III–IV afferents from the exercising muscles (Scott et al., 2000). However, previous studies for testing this hypothesis relied mainly on the technique of post-exercise regional circulatory occlusion, an approach which is highly problematic [see Appendix A in (Poon and Tin, 2013)]. To circumvent this difficulty, Olson et al. (2014) recently reported that IF elicited a significant decrease in exercise V̇E and increase in PaCO2 after 5 min of constant-load submaximal cycling exercise in CHF patients but not in age-matched healthy controls (Fig. S2, Supplementary Data). They interpreted these data as supporting the view that inhibition of group III–IV afferents feedback from locomotor muscle significantly reduced the ventilatory response to exercise in CHF patients. However, the reported hypoventilatory effects of IF during exercise appear to be overestimated, given that the ventilatory response clearly remained nonsteady even after 5 min of submaximal exercise (at 65% peak power, Table 1) in this patient group particularly under IF (Fig. S2, Supplementary Data). Apparently, steady-state exercise V̇E response may take longer than 5 min to achieve in this case, presumably because CHF patients are more prone to lactic acidosis at submaximal exercise levels compared to healthy subjects (Wasserman et al., 1997).

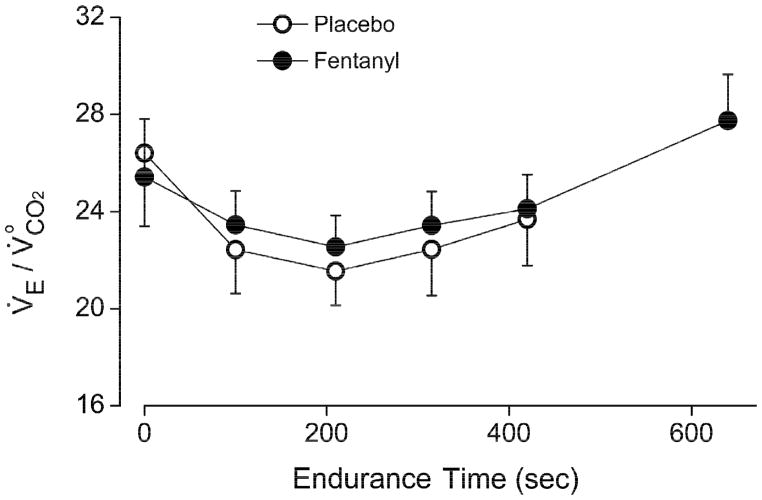

Importantly, a thorough re-analysis of all the reported data in these CHF patients revealed that IF resulted in a significant decrease in V̇E/V̇CO2 and increase in PaCO2 not only during exercise but also in the resting state (Fig. 4), indicating the presence of sustained side effects on V̇E at rest and during exercise that were independent from blockade of group III–IV muscle afferents. Indeed, in (Olson et al., 2014) IF reportedly elicited significant sustained decreases in MAP (but not in heart rate) in both CHF patients and age-matched healthy controls, although these effects were again manifested both at rest and during exercise indicating their non-specificity to muscle afferents blockade [see Tables 3 and 4 of (Olson et al., 2014)]. Such complications revealed the limitations of the IF approach. Although the administration of IF was intended to localize in the lumbar spinal cord, the possibility exists that IF may secondarily influence cardiorespiratory function at rest and during exercise through cephalad or systematic migration of the fentanyl or its action on μ-opioid receptors in other spinal networks unrelated to group III–IV muscle afferents transmission.

Fig. 4.

Intrathecal fentanyl causes similar hypoventilatory effects in CHF patients in the resting state as in exercise. Data (means±SE) for V̇E/V̇CO2 (A) and PaCO2 (B) at rest and at the end of exercise are derived from Tables 3 and 4 of (Olson et al., 2014). *P < 0.05, two-tailed paired Student’s t tests. Note that the hypoventilatory effects of IF during exercise may be overestimated, since the ventilatory response clearly had not attained full steady state even after 5 min of submaximal exercise in these patients (see Fig. S2, Supplementary Data).

These observations suggest that the reported hypoventilatory effects of IF in CHF patients during exercise were comprised of two components: (1) a transient component mediated by group III–IV afferents feedback which was prominent during phase II exercise hyperpnea but not phase III (as with healthy subjects); (2) a long-lasting component which persisted into phase III exercise (as at rest) and was secondary to confounds unrelated to blockade of group III–IV muscle afferents activity. The cause of such confounds at rest and during exercise is unknown but they appear to be unique to these CHF patients. Hence the data reported in (Olson et al., 2014)—when considered in their totality—do not support a role for group III–IV afferents in mediating the augmented steady-state exercise hyperpnea response in CHF patients.

Recently, an alternative hypothesis has been proposed which links the augmented V̇E/V̇CO2 in CHF patients at rest and during steady-state exercise directly to the increased physiological VD/VT in these patients, by positing that the internal model adapted by the respiratory controller may dynamically track the changes in not only V̇CO2 but also VD/VT at rest and during exercise (Poon and Tin, 2013; Poon et al., 2015). As elaborated below, this hypothesis is supported by a wide range of experimental evidences demonstrating a close correlation between V̇E/V̇CO2 and VD/VT in healthy subjects and in CHF and COPD patients.

3.3 Ventilatory effects of IF in COPD patients at rest and during exercise

Like patients with CHF, patients with mild-to-moderate COPD also exhibit an augmented V̇E/V̇CO2 during exercise with near normal PaCO2 (Neder et al., 2015; Paoletti et al., 2011; Teopompi et al., 2014). Gagnon et al. (2012) reported that in patients with COPD, IF also resulted in sustained decreases in V̇E/V̇CO2 during constant-load heavy cycling endurance exercise. Unlike the sustained hypoventilatory effects of IF in CHF patients (Olson et al., 2014), however, the IF-elicited decreases in V̇E/V̇CO2 in this case were observed only during heavy exercise (but not at rest) and were accompanied by concomitant decreases in physiological VD/VT, such that CO2 retention was minimal throughout exercise despite the apparent ventilatory depression [see Fig. 4 in (Gagnon et al., 2012)]. The mechanism underlying the IF-elicited decrease in physiological VD/VT in these patients during heavy exercise is unknown but was presumed to be secondary to corresponding decreases in mean inspiratory airflow and/or reductions in sympathetic outflow, both of which may help to improve pulmonary ventilation-perfusion matching (Gagnon et al., 2012). Such side effects of IF were apparently unique to these COPD patients and were not observed in healthy subjects or CHF patients as demonstrated above.

Again, blockade of group III–IV muscle afferents is unlikely to account for the sustained effects of IF on exercise V̇E/V̇CO2 in COPD patients, given the lack of evidence of such sustained effects mediated by these afferents in healthy subjects and CHF patients (Figs. 2–4) and that PaCO2 remained relatively stable under IF compared with placebo in these COPD patients. What, then, contributed to the reported sustained decreases in V̇E/V̇CO2 during heavy exercise in these COPD patients under IF without causing significant corresponding increases in PaCO2 ? In (Gagnon et al., 2012), the concurrent decreases in physiological VD/VT were deemed a coincidental side effect that helped to stabilize PaCO2 throughout exercise in the face of the decreases in V̇E/V̇CO2 resulting from IF. However, evidence abounds indicating that such correlated decreases in physiological VD/VT and in V̇E/V̇CO2 were by no means an isolated coincidence unique to these COPD patients. In healthy subjects, decreases in physiological VD/VT from rest to moderate exercise are typically compensated for by corresponding decreases in V̇E/V̇CO2 hence keeping PaCO2 relatively stable throughout exercise (Sun et al., 2002; Whipp, 2008), a phenomenon which has been dubbed ‘Whipp’s law’ (Poon and Tin, 2013; Poon et al., 2015). Conversely, increases in VD/VT during dead space loading results in a potentiation of the slope of the V̇E −V̇CO2 relationship (Poon, 1992, 2008; Ward and Whipp, 1980; Wood et al., 2011). Similarly, in patients with CHF or mild-to-moderate COPD the abnormal increases in physiological VD/VT are typically compensated for by corresponding increases in the V̇E−V̇CO2 slope thus keeping PaCO2 relatively stable at rest and during exercise (provided the CHF or COPD diseases are not severe and without other complications) (Neder et al., 2015; Paoletti et al., 2011; Poon, 2014; Poon and Tin, 2013; Poon et al., 2015; Teopompi et al., 2014; Wasserman et al., 1997). The generality of the close correlation between changes in V̇E/V̇CO2 and in VD/VT under a wide range of conditions in health and in disease has led to the recent proposition that the steady-state V̇E response at rest and during moderate exercise is not determined solely by V̇CO2 but is coupled to an apparent (‘real-feel’) metabolic CO2 load defined as (Poon and Tin, 2013; Poon et al., 2015):

| (1) |

In Eq. 1, the apparent metabolic CO2 load ( ) faced by the respiratory controller is greater than V̇CO2 by a factor [1/(1 − VD/VT)] representing the ventilatory inefficiency (reciprocal of ventilatory efficiency) of the pulmonary gas exchanger. By coupling V̇E to the controller is therefore responsive to changes in both V̇CO2 and in VD/VT in order to stabilize PaCO2. Equation 1 has been shown to satisfactorily describe the close correlation between changes in V̇E/V̇CO2 and in VD/VT observed in healthy subjects (Whipp’s law) and in patients with CHF or mild-to-moderate COPD at rest and during moderate exercise (Poon and Tin, 2013; Poon et al., 2015).

To investigate whether Eq. 1 also applies to the reported effects of IF on V̇E/V̇CO2 and physiological VD/VT in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD during prolonged heavy exercise, we plotted (apparent ventilatory equivalent for CO2) vs. exercise endurance time under IF or placebo conditions in these patients using the V̇E/V̇CO2 and VD/VT data derived from (Gagnon et al., 2012). As shown in Fig. 5, was virtually identical for IF and placebo conditions at rest and throughout exercise in these patients. This finding confirms that the sustained decreases in exercise V̇E/V̇CO2 in these patients under IF were secondary to the decreases in ventilatory inefficiency [1/(1 − VD/VT)] (or increases in ventilatory efficiency) as a result of the corresponding decreases in physiological VD/VT under IF. Thus, the sustained decreases in exercise V̇E/V̇CO2 elicited by IF in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD reported in (Gagnon et al., 2012) can be completely accounted for by the controller’s responsiveness to the decreases in secondary to corresponding IF-elicited decreases in physiological VD/VT, independent from blockade of group III–IV muscle afferents.

Fig. 5.

Apparent ventilatory equivalent for at rest and during exercise in a group of patients with COPD after intrathecal injection of fentanyl or placebo. Values are computed based on Eq. 1 using data for V̇E/V̇CO2 and physiological VD/VT derived from Figure 4 in (Gagnon et al., 2012).

4. Conclusion

4.1 Mechanism of ventilatory control during exercise

In conclusion, the available data with IF—when reconciled under Dejours’ framework—do not support the hypothesis that group III–IV muscle afferents are required for a normal steady-state exercise hyperpnea in healthy subjects and in patients with CHF or COPD, although these afferents clearly may help to speed up the transient exercise ventilatory kinetics in healthy subjects. Thus, the ventilatory response to group III–IV muscle afferents input in healthy subjects is not a simple reflex but acts like a high-pass filter with maximum sensitivity during early-phase exercise and subsequent resetting of the response to the baseline in the late phase. In CHF and COPD, IF may elicit sustained decreases in V̇E/V̇CO2 through varying confounding factors independent from the blockade of group III–IV muscle afferents indicating the limitations of the IF approach. In particular, in patients with COPD the attenuation of exercise hyperpnea elicited by IF are completely accounted for by concomitant decreases in ventilatory inefficiency [1/(1 − VD/VT)], such that PaCO2 remains relatively stable throughout exercise compared with placebo. These results support the proposition (Poon et al., 2015; Poon and Tin, 2013) that the steady-state V̇E response at rest and during exercise in healthy subjects and patients with CHF or COPD is mechanistically coupled to (Whipp’s law) as defined in Eq. 1, rather than being reflexively driven by group III–IV muscle afferents feedback per se. We suggest that group III–IV muscle afferents feedback—together with other priming inputs such as carotid chemoafferent feedback and feedforward central command—may contribute to the respiratory controller’s continuing adaptation of an internal model during phase I/II exercise to dynamically track the increase in until the controller can eventually sustain the steady-state optimal exercise hyperpnea response on its own in the long run (Poon et al., 2007). The generality and parsimony of this internal model paradigm in well predicting the exercise ventilatory response in health, CHF and COPD with wide-ranging physiologic/pathophysiologic disturbances in the respiratory apparatus provide a critical litmus test that challenges traditional Sherringtonian feedback/feedforxward reflex control models of exercise hyperpnea (Poon, 2015a, b).

4.2 Mechanism of cardiovascular control during exercise

Lastly, although the present work was focused on calling attention to the transient contribution of group III–IV muscle afferents to exercise hyperpnea, such a caution should equally apply to studies of the cardiovascular response to exercise also. Specifically, the effect of IF on the heart rate response during constant-load heavy exercise in young healthy subjects has been shown to vanish after ~7 min of exercise (Fig. S3, Supplementary Data) (Poon and Tin, 2013) rather than being persistent throughout exercise as previously suggested (Amann et al., 2011). Although the IF-elicited lowering of the MAP response at 3 min of constant-load heavy exercise in young healthy subjects was said to persist until end-exercise at exhaustion [not a fair comparison because the endurance time was significantly longer under placebo condition than IF condition, see Figs. 3 and 4 in (Amann et al., 2011)], subsequent study by these authors has confirmed that “[as] exercise intensity increased and/or exercise duration at high intensity was prolonged, the relative effects of [muscle] afferent blockade on the hyperventilatory, cardioaccelerator and MAP responses were clearly diminished” (Dempsey et al., 2014). Hence, a consensus is emerging that the contribution of group III–IV muscle afferents feedback to the responses in heart rate and MAP during heavy exercise may reset in a time-dependent manner just like a high-pass filter, in a manner similar to the transient contribution of these afferents to the exercise V̇E response (Fig. 1B) or the well-known arterial baroreflex resetting in cardiovascular regulation during exercise (Joyner, 2006; Raven et al., 2006). We believe that all three classical components of cardiovascular regulation—arterial baroafferent feedback, muscle afferents feedback, and feedforward central command—may represent priming inputs that dynamically train the cardiovascular controller in adapting an internal model for long-term cardiovascular regulation during exercise, in a manner akin to that proposed above for the optimal long-term regulation of exercise hyperpnea. Further rigorous research is needed in the future to discriminate the transient vs. long-term effects of group III–IV muscle afferents input on cardiovascular control during moderate exercise in health, CHF and COPD in a definitive manner.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Intrathecal fentanyl slows the transient exercise ventilatory kinetics in humans

Intrathecal fentanyl does not affect steady-state exercise hyperpnea in humans

Intrathecal fentanyl has complex ventilatory effects in COPD and CHF patients

Type III/IV muscle afferents modulate ventilatory response via a high-pass filter

Exercise hyperpnea is coupled to metabolic CO2 load and ventilatory inefficiency

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL093225 and HL067966.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amann M, Blain GM, Proctor LT, Sebranek JJ, Pegelow DF, Dempsey JA. Group III and IV muscle afferents contribute to ventilatory and cardiovascular response to rhythmic exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:966–976. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00462.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amann M, Blain GM, Proctor LT, Sebranek JJ, Pegelow DF, Dempsey JA. Implications of group III and IV muscle afferents for high-intensity endurance exercise performance in humans. J Physiol. 2011;589:5299–5309. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.213769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejours P. Control of respiration in muscular exercise. In: Fenn WO, Rahn H, editors. Handbook of Physiology: Respiration, section 3. American Physiological Society; Washington, D.C: 1964. pp. 631–648. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey JA, Blain GM, Amann M. Are type III–IV muscle afferents required for a normal steady-state exercise hyperpnoea in humans? J Physiol. 2014;592:463–474. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.261925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffin J. The fast exercise drive to breathe. J Physiol. 2014;592:445–451. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.258897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon P, Bussieres JS, Ribeiro F, Gagnon SL, Saey D, Gagne N, Provencher S, Maltais F. Influences of spinal anesthesia on exercise tolerance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2012;186:606–615. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0404OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozal D, Marcus CL, Ward SL, Keens TG. Ventilatory responses to passive leg motion in children with congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:761–768. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.2.8564130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner MJ. Baroreceptor function during exercise: resetting the record. Exp Physiol. 2006;91:27–36. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.032102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, Lindhard J. The regulation of respiration and circulation during the initial stages of muscular work. J Physiol. 1913;47:112–136. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1913.sp001616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugliani R, Whipp BJ, Seard C, Wasserman K. Effect of bilateral carotid-body resection on ventilatory control at rest and during exercise in man. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1105–1111. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111112852002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald SM, Tin C, Song G, Poon CS. Use-dependent learning and memory of the Hering-Breuer inflation reflex in rats. Exp Physiol. 2009;94:269–278. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.045344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neder JA, Arbex FF, Alencar MC, O’Donnell CD, Cory J, Webb KA, O’Donnell DE. Exercise ventilatory inefficiency in mild to end-stage COPD. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:377–387. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00135514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson TP, Joyner MJ, Eisenach JH, Curry TB, Johnson BD. Influence of locomotor muscle afferent inhibition on the ventilatory response to exercise in heart failure. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:414–426. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.075937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P, De Filippis F, Fraioli F, Cinquanta A, Valli G, Laveneziana P, Vaccaro F, Martolini D, Palange P. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) in pulmonary emphysema. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;179:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson DJ. Defining the neurocircuitry of exercise hyperpnoea. J Physiol. 2014;592:433–444. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.261586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon CS. Potentiation of exercise ventilatory response by airway CO2 and dead space loading. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:591–595. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.2.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon CS. The classic potentiation of exercise ventilatory response by increased dead space in humans is more than short-term modulation. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:390. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90543.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon CS. Exercise ventilation-CO2 output relationship in COPD and heart failure: a tale of two abnormalities. Respir Care. 2014;59:1157–1159. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon CS. Precedence and autocracy evince optimization and decision-making in breathing control. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2015a;118(12):1558. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00229.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon CS. Reply to Dr. S.A. Ward: Whipp’s law, Comroe’s law and generality of the optimization model of ventilatory control. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2015b;216:94–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon CS, Merfeld DM. Internal models: the state of the art. J Neural Eng. 2005;2 doi: 10.1088/1741-2552/1082/1083/E1001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poon CS, Song G. Bidirectional plasticity of pontine pneumotaxic postinspiratory drive: implication for a pontomedullary respiratory central pattern generator. Prog Brain Res. 2014;209:235–254. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63274-6.00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon CS, Tin C. Mechanism of augmented exercise hyperpnea in chronic heart failure and dead space loading. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013;186:114–130. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon CS, Tin C, Song G. Submissive hypercapnia: Why COPD patients are more prone to CO2 retention than heart failure patients. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2015;216:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon CS, Tin C, Yu Y. Homeostasis of exercise hyperpnea and optimal sensorimotor integration: the internal model paradigm. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;159:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.02.020. discussion 14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon CS, Young DL. Nonassociative learning as gated neural integrator and differentiator in stimulus-response pathways. Behav Brain Funct. 2006;2:29. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-2-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon CS, Young DL, Siniaia MS. High-pass filtering of carotid-vagal influences on expiration in rat: role of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Neurosci Lett. 2000;284:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00993-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven PB, Fadel PJ, Ogoh S. Arterial baroreflex resetting during exercise: a current perspective. Exp Physiol. 2006;91:37–49. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.032250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley MS, Cooper CB. Ventilatory and gas exchange responses during heavy constant work-rate exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:98–104. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200201000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott AC, Francis DP, Davies LC, Ponikowski P, Coats AJ, Piepoli MF. Contribution of skeletal muscle ‘ergoreceptors’ in the human leg to respiratory control in chronic heart failure. J Physiol. 2000;529(Pt 3):863–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00863.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siniaia MS, Young DL, Poon CS. Habituation and desensitization of the Hering-Breuer reflex in rat. J Physiol. 2000;523(Pt 2):479–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00479.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song G, Tin C, Poon CS. Multiscale fingerprinting of neuronal functional connectivity. Brain Struct Funct. 2015;220(5):2967–82. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0838-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XG, Hansen JE, Garatachea N, Storer TW, Wasserman K. Ventilatory efficiency during exercise in healthy subjects. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2002;166:1443–1448. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2202033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teopompi E, Tzani P, Aiello M, Ramponi S, Visca D, Gioia MR, Marangio E, Serra W, Chetta A. Ventilatory response to carbon dioxide output in subjects with congestive heart failure and in patients with COPD with comparable exercise capacity. Respir Care. 2014;59:1034–1041. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tin C, Poon CS. Internal models in sensorimotor integration: perspectives from adaptive control theory. J Neural Eng. 2005;2:S147–163. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/2/3/S01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tin C, Poon CS. Control of breathing: integration of adaptive reflexes. In: Jaeger D, Jung R, editors. Encyclopedia of Computational Neuroscience. Springer; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ward SA, Whipp BJ. Ventilatory control during exercise with increased external dead space. J Appl Physiol. 1980;48:225–231. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.48.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman K, Whipp BJ, Koyal SN, Cleary MG. Effect of carotid body resection on ventilatory and acid-base control during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1975;39:354–358. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.39.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman K, Zhang YY, Gitt A, Belardinelli R, Koike A, Lubarsky L, Agostoni PG. Lung function and exercise gas exchange in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1997;96:2221–2227. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whipp BJ. Control of the exercise hyperpnea: the unanswered question. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;605:16–21. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-73693-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whipp BJ, Wasserman K. Oxygen uptake kinetics for various intensities of constant-load work. J Appl Physiol. 1972;33:351–356. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.33.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood HE, Mitchell GS, Babb TG. Short-term modulation of the exercise ventilatory response in younger and older women. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;179:235–247. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young DL, Eldridge FL, Poon CS. Integration-differentiation and gating of carotid afferent traffic that shapes the respiratory pattern. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:1213–1229. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00639.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.