Abstract

Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO)-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation is reportedly diminished during exercise performed at a high (700 W) relative to moderate (400 W) rate of metabolic heat production. The present study evaluated whether this impairment results from increased oxidative stress associated with an accumuluation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) during high intensity exercise. On two separate days, 11 young (mean ± SD, 24 ± 4 years) males cycled in the heat (35°C) at a moderate (500 W) or high (700 W) rate of metabolic heat production. Each session included two 30 min exercise bouts followed by 20 and 40 min of recovery, respectively. Cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC) was monitored at four forearm skin sites continuously perfused via intradermal microdialysis with: (1) lactated Ringer solution (Control); (2) 10 mm ascorbate (Ascorbate); (3) 10 mm l-NAME; or (4) 10 mm ascorbate + 10 mm l-NAME (Ascorbate + l-NAME). At the end of each 500 W exercise bout, CVC was attenuated with l-NAME (∼35% CVCmax) and Ascorbate + l-NAME (∼43% CVCmax) compared to Control (∼60% CVCmax; all P < 0.04); however, Ascorbate did not modulate CVC during exercise (∼60% CVCmax; both P > 0.87). Conversely, CVC was elevated with Ascorbate (∼72% CVCmax; both P < 0.03) but remained similar to Control (∼59% CVCmax) with l-NAME (∼50% CVCmax) and Ascorbate + l-NAME (∼47% CVCmax; all P > 0.05) at the end of both 700 W exercise bouts. We conclude that oxidative stress associated with an accumulation of ascorbate-sensitive ROS impairs NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation during intense exercise.

Key points

Recent work demonstrates that nitric oxide (NO) contributes to cutaneous vasodilatation during moderate (400 W of metabolic heat production) but not high (700 W of metabolic heat production) intensity exercise bouts performed in the heat (35°C).

The present study evaluated whether the impairment in NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation was the result of a greater accumulation of reactive oxygen species during high (700 W of metabolic heat production) relative to moderate (500 W of metabolic heat production) intensity exercise.

It was shown that local infusion of ascorbate (an anti-oxidant) improves NO-dependent forearm cutaneous vasodilatation during high intensity exercise in the heat.

These findings provide novel insight into the physiological mechanisms governing cutaneous blood flow during exercise-induced heat stress and provide direction for future research exploring whether oxidative stress underlies the impairments in heat dissipation that may occur in older adults, as well as in individuals with pathophysiological conditions such as type 2 diabetes.

Introduction

During whole-body heat stress, cutaneous vasodilatation is crucial for the maintenance of a stable core body temperature in humans. Numerous studies have identified a role for nitric oxide (NO) as an important modulator of this response. Specifically, local inhibition of NO production via non-selective NO synthase blockade has been shown to attenuate cutaneous vasodilatation in young adults during whole-body passive heating (Kellogg et al. 1998; Holowatz et al. 2003; Holowatz et al. 2006a,b; Wong & Minson, 2006; Stanhewicz et al. 2012; Brunt et al. 2013; Swift et al. 2014) and exercise-induced heat stress (Welch et al. 2009; Fujii et al. 2014; McGinn et al. 2014a,b; McNamara et al. 2014).

Recently, we demonstrated that NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation was diminished in young physically active males during high (fixed rate of heat production of 700 W) compared to moderate (400 W) intensity intermittent exercise performed in the heat (35°C) (Fujii et al. 2014). This may be the result of a greater accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) during the high relative to moderate intensity exercise. Indeed, NO can react with ROS such as superoxide to form peroxynitrite, which itself is a potent ROS, resulting in diminished NO bioavailability (Radi et al. 1991; Squadrito & Pryor, 1998; Holowatz, 2011; Mortensen & Lykkesfeldt, 2014). Therefore, a marked accumulation of ROS during high intensity exercise could impair NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation. In support of this notion, a recent in vivo human study demonstrated that elevations in oxidative stress are associated with attenuations in the cutaneous vasodilatory response to whole-body heating (Holowatz et al. 2006a).

During aerobic exercise, ROS production increases as a result of elevated oxidative metabolism (Gomes et al. 2012). Under most circumstances, the ROS produced are scavenged by endogenous anti-oxidants, preventing oxidative tissue damage (i.e. oxidative stress) (Gomes et al. 2012). However, high intensity exercise may overwhelm endogenous anti-oxidant capacity, leading to an accumulation of ROS (Lovlin et al. 1987; Goto et al. 2003; Seifi-Skishahr et al. 2008; Sureda et al. 2015). Specifically, circulating malondialdehyde, a marker of oxidative stress, remains elevated after 30 min of high (75% of peak rate of oxygen consumption;  ) but not low (50%

) but not low (50%  ) intensity cycling (Goto et al. 2003). Exercise in a hot environment may also exacerbate the accumulation of ROS, as indicated by a recent study reporting comparatively greater levels of malondialdehyde after intense exercise (75–80%

) intensity cycling (Goto et al. 2003). Exercise in a hot environment may also exacerbate the accumulation of ROS, as indicated by a recent study reporting comparatively greater levels of malondialdehyde after intense exercise (75–80%  ) in the heat (∼32°C) compared to an equivalent exercise bout performed in cool (∼12°C) ambient conditions (Sureda et al. 2015). Altogether, these results suggest that an accumulation of ROS during high intensity exercise may impair NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation, especially in hot environments.

) in the heat (∼32°C) compared to an equivalent exercise bout performed in cool (∼12°C) ambient conditions (Sureda et al. 2015). Altogether, these results suggest that an accumulation of ROS during high intensity exercise may impair NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation, especially in hot environments.

The present study aimed to determine whether intradermal infusion of ascorbate (a non-selective anti-oxidant) is capable of modulating cutaneous vasodilatation during high intensity exercise in the heat (35°C; 20% relative humidity) and, if so, whether this effect is mediated through increases in NO bioavailability. An intermittent exercise protocol was employed to assess whether the influence of ascorbate on the heat loss responses is modulated in a subsequent exercise bout, for which the accumulation of ROS is presumably greater compared to the initial bout. Given previous work demonstrating that NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation is diminished during high intensity exercise only (Fujii et al. 2014), we hypothesized that the contribution of NO to the cutaneous vasodilatory response would be augmented with local infusion of ascorbate during high but not moderate intensity exercise.

Methods

Ethical approval

The current experimental protocol was approved by the University of Ottawa Health Sciences Ethics Board and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written and informed consent was obtained from all volunteers prior to their participation in the study.

Participants

Eleven healthy, habitually active (2–4 days per week of structured physical activity; ≥30 min in duration) young males participated in the present study. All participants were free of cardiovascular, metabolic or respiratory disease. Participants had no history of autonomic or skin disorders, were non-smokers and were not taking any prescription or over-the-counter medications at the time of the study. The physical characteristics of the participants (mean ± SD) were: age, 24 ± 4 years; height, 1.75 ± 0.06 m; body mass, 79 ± 10 kg; body surface area, 1.9 ± 0.1 m2; body fat percentage, 14 ± 5% and  , 45 ± 7 ml O2 kg−1 min−1.

, 45 ± 7 ml O2 kg−1 min−1.

Experimental procedures

Participants volunteered for one screening and two experimental sessions. All participants abstained from prescription and over-the-counter medications and vitamin supplements (including vitamin C and E) for a minimum of 48 h prior to each session, as well as alcohol, caffeine and heavy exercise for at least 24 h before each session. Furthermore, participants were instructed to not consume any food 2 h before each session. During the screening session, body height, mass, density, surface area, fat percentage and  were determined. Body height was measured using a stadiometer (model 2391; Detecto, Webb City, MO, USA), whereas body mass was measured using a high-performance digital weighing terminal (model CBU150X; Mettler Toledo Inc., Mississauga, ON, Canada). Body surface area was subsequently calculated from the measurements of body height and mass (Dubois & Dubois, 1916). Body density was measured using the hydrostatic weighing technique and used to calculate body fat percentage (Siri, 1956).

were determined. Body height was measured using a stadiometer (model 2391; Detecto, Webb City, MO, USA), whereas body mass was measured using a high-performance digital weighing terminal (model CBU150X; Mettler Toledo Inc., Mississauga, ON, Canada). Body surface area was subsequently calculated from the measurements of body height and mass (Dubois & Dubois, 1916). Body density was measured using the hydrostatic weighing technique and used to calculate body fat percentage (Siri, 1956).  was assessed during a maximal incremental cycling protocol performed on a semi-recumbent cycle ergometer (Corival; Lode BV, Groningen, The Netherlands). Participants were instructed to maintain a pedalling cadence of 60–90 revolutions min−1 at a starting workload of 100 W. Thereafter, the work load was increased by 20 W min−1 until volitional fatigue and/or the participants could no longer maintain a pedalling cadence ≥50 revolutions min−1. Throughout the maximal cycling protocol, oxygen uptake was monitored by an automated indirect calorimetry system (MCD Medgraphics Ultima Series; MGC Diagnostics, MN, USA).

was assessed during a maximal incremental cycling protocol performed on a semi-recumbent cycle ergometer (Corival; Lode BV, Groningen, The Netherlands). Participants were instructed to maintain a pedalling cadence of 60–90 revolutions min−1 at a starting workload of 100 W. Thereafter, the work load was increased by 20 W min−1 until volitional fatigue and/or the participants could no longer maintain a pedalling cadence ≥50 revolutions min−1. Throughout the maximal cycling protocol, oxygen uptake was monitored by an automated indirect calorimetry system (MCD Medgraphics Ultima Series; MGC Diagnostics, MN, USA).  was taken as the highest average rate of oxygen uptake measured over 30 s.

was taken as the highest average rate of oxygen uptake measured over 30 s.

On the day of the experimental sessions, participants reported to the laboratory well-hydrated (ensured by consuming 500 ml of water the night prior to and 2 h before the experimental session). Upon arrival, participants provided a urine sample for the measurement of urine specific gravity and voided the remainder of their bladder prior to a measurement of nude body mass. Participants then rested in a semi-recumbent position in a thermoneutral room (25°C) and four microdialysis fibres were inserted into the dermal layer of skin on the dorsal side of the left forearm. All microdialysis fibres were placed in the unanaesthetized skin using an aseptic technique by first inserting a 25-gauge needle that exited the skin ∼2.5 cm from the insertion point. The microdialysis fibre was then threaded through the lumen of the needle, which was subsequently withdrawn, leaving the microdialysis fibre in place. Each fibre was separated from adjacent fibres by at least 4 cm and secured with surgical tape. Thereafter, the microdialysis fibres were perfused with lactated Ringer solution at a rate of 4 μl min− 1 via a perfusion pump (model 400; CMA Microdialysis, Solna, Sweden) for ∼60 min to allow for the resolution of the local hyperemic response. During this time, each site was instrumented for the measurement of local cutaneous blood flow (see below).

After the resolution period, participants entered a thermally controlled chamber (Can-Trol Environmental Systems Limited, Markham, ON, Canada) regulated to 35°C and 20% relative humidity. Participants then rested quietly on a semi-recumbent cycle ergometer (Corival; Lode BV) and the microdialysis probes were perfused at a rate of 4 μl min−1 in a counter-balanced manner with either (1) lactated Ringer serving as a control (Control); (2) 10 mm ascorbate (Ascorbate; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), an anti-oxidant; (3) 10 mm l-NAME (Sigma-Aldrich), a non-selective NO synthase inhibitor; or (4) a combination of 10 mm ascorbate and 10 mm l-NAME (Ascorbate + l-NAME). These concentrations were chosen based on previous studies employing intradermal microdialysis for ascorbate (Holowatz et al. 2006a; Stewart et al. 2008; Fujii et al. 2015) and l-NAME (Holowatz et al. 2003; Holowatz et al. 2006a,b; Fujii et al. 2014; McGinn et al. 2014a,b; Stapleton et al. 2014; Sureda et al. 2015) and have been shown to influence cutaneous vasodilatation (Holowatz et al. 2003; Holowatz et al. 2006a,b; Stewart et al. 2008; Welch et al. 2009; Fujii et al. 2014; McGinn et al. 2014a,b; Swift et al. 2014). Each drug was perfused for a minimum of 60 min prior to the experimental protocol and was continued throughout. Thus, ∼120 min was allowed between the placement of the microdialysis fibres and the start of baseline measurements (i.e. 60 min resolution period plus 60 min of drug perfusion) to ensure that any local trauma associated with insertion of the needle and/or microdialysis fibre had subsided (Hodges et al. 2009).

After 10 min of baseline data collection, participants performed two successive 30 min bouts of semi-recumbent cycling with the first and second exercise bouts followed by 20 and 40 min of recovery, respectively. Thereafter, all measurements were stopped and each microdialysis fibre was perfused with 50 mm sodium nitroprusside (Hospira, Lake Forest, IL, USA) at a rate of 6 μl min−1 to determine maximum cutaneous blood flow. Once a stable plateau in cutaneous blood flow was achieved (∼20–30 min), a measurement of blood pressure was taken for the determination of maximal cutaneous vascular conductance (CVCmax). After the observation of a stable plateau, the remaining instrumentation was removed and a final nude body mass measurement was obtained. This protocol was performed in a counterbalanced manner on two separate days. The only difference between the two sessions was the intensity of exercise, quantified as the absolute rate of metabolic heat production to ensure a similar thermal drive for whole-body heat loss (Gagnon et al. 2013; Kenny & Jay, 2013). In one session, both exercise bouts were performed at a moderate intensity, where the rate of metabolic heat production was maintained at 500 W (moderate intensity condition, equivalent to 52 ± 6%  , 93 ± 6 W of external work load), whereas, in the other session, both exercise bouts were performed at a high intensity defined as a metabolic heat production of 700 W (high intensity condition, equivalent to 71 ± 8%

, 93 ± 6 W of external work load), whereas, in the other session, both exercise bouts were performed at a high intensity defined as a metabolic heat production of 700 W (high intensity condition, equivalent to 71 ± 8%  , 127 ± 8 W of external work load). All 11 participants completed the moderate intensity condition; however, only 10 participants were able to complete the high intensity condition.

, 127 ± 8 W of external work load). All 11 participants completed the moderate intensity condition; however, only 10 participants were able to complete the high intensity condition.

Measurements

A paediatric thermocouple probe of ∼2 mm in diameter (Mon-a-therm; Mallinckrodt Medical, St Louis, MO, USA) inserted through the nose 40 cm past the entrance of the nostril was used for the continuous measurement of oesophageal temperature. Mean skin temperature was calculated using six skin sites weighted to the regional proportions as reported by (Hardy & Dubois, 1938): upper back, 21%; chest, 21%; biceps, 19%; quadriceps, 9.5%; hamstring, 9.5%; and 9.5% and front calf, 20%. All temperature data were collected using a data acquisition module at a sampling rate of 15 s and simultaneously displayed and recorded in spreadsheet format on a personal computer with LabVIEW software, version 7.0 (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA).

Arterial blood pressure was monitored prior to and at 5 min intervals during the experimental protocol, as well as during the plateau phase of CVCmax. Systolic and diastolic pressures were obtained using manual auscultation with a validated mercury column sphygmomanometer (Baumanometer Standby Model; WA Baum Co., Copiague, NY, USA). Mean arterial pressure was calculated as diastolic pressure plus one-third pulse pressure (i.e., the difference between systolic and diastolic pressures). Heart rate was recorded continuously and stored every 15 s using a Polar coded WearLink and transmitter, Polar RS400 interface and Polar Trainer 5 software (Polar Electro, Kempele, Finland).

Cutaneous red blood cell flux, expressed in perfusion units, was locally measured at a sampling rate of 32 Hz with laser-Doppler flowmetry (PeriFlux System 5000; Perimed, Stockholm, Sweden). Integrated laser-Doppler flowmetry probes with a 7-laser array (Model 413; Perimed) were centred directly over each microdialysis fibre. Cutaneous blood flow responses were evaluated as a percentage of the maximal cutaneous blood flow response observed during the administration of 50 mm sodium nitroprusside. Furthermore, CVC was calculated as red blood cell flux divided by mean arterial pressure and presented as a percentage of CVCmax, as determined during the maximal cutaneous blood flow protocol.

Metabolic energy expenditure was measured using indirect calorimetry. The oxygen (error of ± 0.01%) and carbon dioxide (error of ± 0.02%) concentrations of expired air were measured using electrochemical gas analysers (AMETEK model S-3A/1 and CD3A; Applied Electrochemistry, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). A gas mixture of known concentrations (∼17% oxygen, ∼4% carbon dioxide, balance nitrogen) and a 3 L syringe were used to calibrate the gas analysers and turbine ventilometer, respectively, ∼20 min prior to the start of baseline data collection. Participants wore a full face mask (Model 7600 V2; Hans-Rudolph, Kansas City, MO, USA) attached to a two-way T-shape non-rebreathing valve (Model 2700; Hans-Rudolph). Metabolic rate was calculated from measurements of oxygen uptake and respiratory exchange ratio obtained every 30 s. Metabolic heat production during cycling was subsequently calculated as metabolic rate minus external work (Kenny & Jay, 2013).

Data analysis

Baseline resting values were obtained by averaging measurements performed over the first 5 min of the 10 min baseline period, whereas values at the start of the first exercise bout (time 0) were obtained by averaging the final 5 min of this period. Local forearm CVC and cutaneous blood flow at each treatment site, as well as core body and skin temperatures and heart rate data during each exercise bout and recovery period, were obtained by averaging data collected during the final 5 min of each 10 min period. Furthermore, blood pressure data were presented as an average of the two measurements taken over each 10 min interval. Local forearm CVCmax was determined from averaged CVC data over a minimum of 2 min once a plateau was attained during sodium nitroprusside administration performed at the end of each experimental protocol.

Statistical analysis

For each exercise intensity condition, local forearm CVC was analysed at baseline rest and the start of the first exercise bout (time 0) using a one-way repeated measures ANOVA with a factor of treatment site. During exercise, CVC was analysed using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA for each intensity condition with the factors of treatment site and time. Similarly, the local cutaneous vasodilatory response was analysed during each recovery using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA with the factors of treatment site and time. Cutaneous blood flow responses were compared between treatment sites in each intensity condition using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA. In addition, similar analysis was used to compare CVC at the Control site, as well as body temperature (i.e. core and skin temperatures) and cardiovascular (i.e. blood pressure and heart rate) responses between intensity conditions. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA with the factors of treatment site and intensity condition was used to compare CVCmax (expressed as perfusion units mmHg−1) obtained during sodium nitroprusside administration between each treatment site in both trials. Furthermore, pre-trial body mass and the percent change in body mass during the experimental sessions were compared between conditions using two-tailed Student’s paired samples t test. When a significant main effect was observed, post hoc analysis was carried out using two-tailed Student’s paired samples t tests adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Holm–Bonferroni procedure. For all analyses, P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All values are reported as the mean ± 95% confidence interval (i.e. 1.96 × SEM).

Results

Cutaneous vascular response

Comparison between intensity conditions

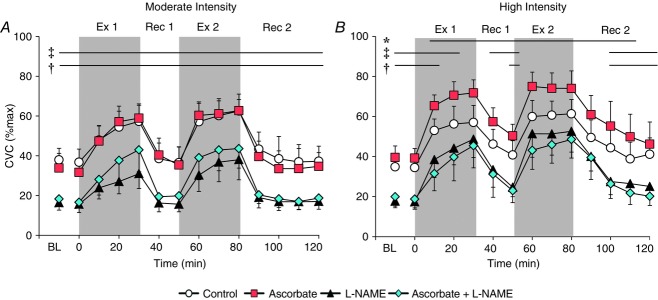

No interaction of intensity and time (P = 0.45) or main effect of intensity condition (P = 0.39) was observed on CVC at the Control site. Therefore, CVC at the Control site was similar between intensity conditions throughout the intermittent exercise protocol (Fig.1).

Figure 1.

CVC during two successive exercise bouts

The successive exercise bouts were performed at a fixed rate of metabolic heat production of 500 W (moderate intensity condition; A) and 700 W (high intensity condition; B). Throughout the intermittent exercise protocol, four skin sites were continuously perfused via intradermal microdialysis with:(1) lactated Ringer solution (Control, open circles); (2) 10 mm ascorbate (Ascorbate, red squares), an anti-oxidant; (3) 10 mm l-NAME (black triangles) to inhibit NO synthase activity; or (4) a combination of 10 mm ascorbate + 10 mm l-NAME (Ascorbate + l-NAME, blue diamonds). Values are the mean ± 95% confidence interval. Each data point during exercise and recovery represents an average of the last 5 min of each 10 min interval. BL, baseline resting; Ex 1, first exercise; Rec 1, first recovery; Ex 2, second exercise; Rec 2, second recovery. *Control significantly different from Ascorbate. ‡Control significantly different from l-NAME. †Control significantly different from Ascorbate + l-NAME (all P < 0.05).

Moderate intensity exercise (500 W)

Prior to the first exercise bout, CVC was reduced at the l-NAME (P < 0.01) and Ascorbate + l-NAME (P < 0.01) skin sites compared to the untreated Control site (main effect of treatment, P < 0.01; Fig.1A); however, responses were similar between the Control and the Ascorbate sites (P = 0.62). Similarly, CVC during both exercise bouts and recovery periods (main effect of treatment site, both P < 0.01) was greater at the Control skin site relative to the l-NAME (all P ≤ 0.02) and Ascorbate + l-NAME (all P ≤ 0.04) sites but similar to Control at the Ascorbate site (all P ≥ 0.16).

High intensity exercise (700 W)

In parallel to the moderate exercise condition, CVC was attenuated at the l-NAME (P < 0.01) and Ascorbate + l-NAME (P = 0.02) sites but similar at the Ascorbate skin site (P = 0.15) compared to Control during baseline rest in the high intensity condition (main effect of treatment, P < 0.01; Fig.1B). During exercise, CVC was reduced from Control for the initial 20 and 10 min of the first exercise bout at the l-NAME (both P ≤ 0.02) and Ascorbate + l-NAME (P ≤ 0.05) skin sites, respectively. However, no differences were observed at these sites relative to Control for the remainder of the first exercise bout (all P ≥ 0.06). Moreover, CVC measured at the l-NAME (all P ≥ 0.07) and Ascorbate + l-NAME (all P ≥ 0.06) skin sites was similar to Control for the full 30 min duration of the second exercise bout (Fig.1B). At the Ascorbate site, CVC was elevated relative to Control for the entirety of both 30 min exercise bouts (all P ≤ 0.01).

After the first exercise bout, CVC at the l-NAME site was significantly reduced from the Control site throughout the duration of the first recovery period (both P ≤ 0.03), whereas CVC was attenuated at the Ascorbate + l-NAME site relative to Control at the end of the 20 min first recovery (P < 0.01) (main effect of treatment site, P < 0.01; Fig.1B). In the second recovery period, CVC was attenuated at the l-NAME (all P ≤ 0.03) and Ascorbate + l-NAME (all P ≤ 0.03) skin sites from the 20 min time point until the end of the 40 min extended recovery period. Moreover, CVC was elevated at the Ascorbate site compared to Control throughout both recovery periods (all P ≤ 0.03), although CVC at the Ascorbate site returned to values similar to Control by the end of the extended second recovery (P = 0.15).

Maximal CVC

No interaction of exercise condition and treatment site (P = 0.28) and no main effect of exercise condition (P = 0.10) or treatment (P = 0.09) were observed on CVCmax during administration of 50 mm sodium nitroprusside. Thus, CVCmax was similar between treatment sites and did not differ between the moderate and the high intensity exercise conditions (Table1).

Table 1.

CVCmax during local administration of 50 mm sodium nitroprusside

| Control | Ascorbate | l-NAME | Ascorbate + l-NAME | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVCmax (PU mmHg−1) | ||||

| Moderate intensity | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.4 |

| High intensity | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.5 |

Values are the mean ± 95% confidence interval. Moderate intensity, exercise performed at fixed rate of metabolic heat production of 500 W. High intensity, exercise performed at fixed rate of metabolic heat production of 700 W. CVCmax in perfusion units (PU mmHg−1) measured at the four skin sites previously perfused with: (1) lactated Ringer solution (Control); (2) 10 mm ascorbate (Ascorbate), an anti-oxidant; (3) 10 mm l-NAME to inhibit NO synthase activity; or (4) a combination of 10 mm ascorbate + 10 mm l-NAME (Ascorbate + L-NAME) throughout the intermittent exercise protocol. No statistically significant differences were observed.

Cutaneous blood flow response

Cutaneous blood flow was attenuated at the l-NAME (all P ≤ 0.01) and Ascorbate + l-NAME (all P ≤ 0.02) skin sites relative to the Control site during baseline rest, as well as each exercise bout and recovery period in the moderate intensity condition (main effect of treatment site, P < 0.01; Table2). Conversely, no differences between the Control and Ascorbate sites were observed (all P ≥ 0.11). In the high intensity exercise condition, l-NAME and Ascorbate + l-NAME reduced cutaneous blood flow relative to Control during baseline rest (both P ≤ 0.02) and each recovery period (all P ≤ 0.01) but not during either exercise bout (all P ≥ 0.06) (main effect of treatment site, P < 0.01; Table2). Furthermore, cutaneous blood flow was elevated at the Ascorbate site compared to Control during both exercise bouts (both P ≤ 0.03) and recovery periods (both P ≤ 0.03) with the exception of the 40 min time point of the second recovery (P = 0.15).

Table 2.

Cutaneous blood flow responses (% of maximum cutaneous blood flow) at rest and during the two exercise/recovery cycles

| Exercise 1 | Recovery 1 | Exercise 2 | Recovery 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | 30 min | 20 min | 30 min | 20 min | 40 min | |

| Moderate intensity | ||||||

| Control | 41 ± 7 | 66 ± 9 | 37 ± 8 | 71 ± 9 | 40 ± 11 | 38 ± 7 |

| Ascorbate | 35 ± 9 | 68 ± 8 | 35 ± 10 | 71 ± 6 | 33 ± 9 | 34 ± 8 |

| l-NAME | 18 ± 4* | 35 ± 8* | 16 ± 4* | 43 ± 11* | 18 ± 4* | 17 ± 3* |

| Ascorbate + l-NAME | 20 ± 3* | 48 ± 12* | 20 ± 5* | 49 ± 10* | 19 ± 5* | 19 ± 4* |

| High intensity | ||||||

| Control | 38 ± 7 | 70 ± 10 | 42 ± 7 | 73 ± 8 | 44 ± 8 | 42 ± 8 |

| Ascorbate | 44 ± 6 | 87 ± 9* | 52 ± 7* | 89 ± 11* | 54 ± 12* | 47 ± 11 |

| l-NAME | 19 ± 3* | 59 ± 10 | 25 ± 4* | 61 ± 12 | 27 ± 5* | 26 ± 5 * |

| Ascorbate + l-NAME | 21 ± 5* | 56 ± 14 | 23 ± 6* | 58 ± 11 | 26 ± 6* | 20 ± 4* |

Values are the mean ± 95% confidence interval. Moderate intensity, exercise performed at fixed rate of metabolic heat production of 500 W. High intensity, exercise performed at fixed rate of metabolic heat production of 700 W. Cutaneous blood flow responses represent an average of the final 5 min of the corresponding time period.

P < 0.05 vs. Control.

Hydration status, body temperature and cardiovascular responses

Prior to the experimental trial, urine specific gravity was 1.010 ± 0.004 and 1.011 ± 0.005 in the moderate and high intensity conditions, respectively, indicating that participants were adequately hydrated before each session (Sawka et al. 2007). Furthermore, no pre-trial differences in urine specific gravity (P = 0.76) or body mass (moderate intensity, 79 ± 6 kg; high intensity, 80 ± 6 kg; P = 0.36) were observed between conditions. However, exercise performed at high intensity resulted in a greater reduction in body mass (−2.7 ± 0.5%) relative to the moderate intensity exercise condition (−1.8 ± 0.2%; P < 0.01).

The time course changes in body (i.e. core and mean skin temperature) temperature and cardiovascular (i.e. blood pressure and heart rate) responses are presented in Table3. No differences in these variables were observed during baseline resting between exercise intensity conditions (all P > 0.12). Compared to the moderate intensity exercise condition, a greater oesophageal temperature response was measured during both exercise bouts and at the 20 min time point of the second recovery in the high intensity exercise condition (all P < 0.01). In contrast, no differences in mean skin temperature were observed between conditions during either exercise/recovery cycle (main effect of intensity condition, P = 0.48). Furthermore, mean arterial pressure was greater in the high relative to moderate exercise condition during both the first and second exercise bouts (both P ≤ 0.02); however, responses were similar during the recovery periods (all P ≥ 0.06). Finally, heart rate in the high exercise intensity condition was significantly elevated from responses measured in the moderate intensity trial throughout both exercise and recovery periods (all P ≤ 0.03).

Table 3.

Body temperatures and cardiovascular variables at rest and during the two exercise/recovery cycles

| Exercise 1 | Recovery 1 | Exercise 2 | Recovery 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | 30 min | 20 min | 30 min | 20 min | 40 min | |

| Oesophageal temperature (°C) | ||||||

| Moderate intensity | 37.00 ± 0.10 | 37.61 ± 0.19* | 37.33 ± 0.14* | 37.82 ± 0.19*‡ | 37.44 ± 0.16*‡ | 37.44 ± 0.13*‡ |

| High intensity | 36.91 ± 0.07 | 38.00 ± 0.19*† | 37.34 ± 0.11* | 38.45 ± 0.20*‡† | 37.66 ± 0.10*‡† | 37.54 ± 0.10*‡ |

| Mean skin temperature (°C) | ||||||

| Moderate intensity | 35.04 ± 0.26 | 35.56 ± 0.38* | 35.11 ± 0.31 | 35.59 ± 0.39* | 35.16 ± 0.36 | 34.86 ± 0.41‡ |

| High intensity | 34.95 ± 0.27 | 35.65 ± 0.29* | 35.36 ± 0.24* | 35.78 ± 0.34* | 35.44 ± 0.30* | 35.03 ± 0.33‡ |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | ||||||

| Moderate intensity | 89 ± 4 | 97 ± 5* | 85 ± 5* | 95 ± 5* | 88 ± 7‡ | 85 ± 5* |

| High intensity | 91 ± 4 | 104 ± 5*† | 87 ± 5* | 102 ± 6*† | 84 ± 5* | 87 ± 5* |

| Heart rate (beats min–1) | ||||||

| Moderate intensity | 71 ± 6 | 130 ± 11* | 85 ± 7* | 135 ± 12*‡ | 88 ± 7*‡ | 86 ± 7* |

| High intensity | 70 ± 7 | 153 ± 8*† | 93 ± 7*† | 161 ± 8*‡† | 99 ± 8*‡† | 94 ± 7*† |

Values are the mean ± 95% confidence interval. Moderate intensity, exercise performed at fixed rate of metabolic heat production of 500 W. High intensity, exercise performed at fixed rate of metabolic heat production of 700 W. Oesophageal and mean skin temperatures, as well as heart rate responses, represent an average of the final 5 min of the corresponding time period. Mean arterial pressure values represents an average of two measurements taken over the final 10 min of the corresponding time period.

P < 0.05 vs. Rest.

P < 0.05 Exercise 1 vs. Exercise 2 or Recovery 1 vs. Recovery 2.

P < 0.05 vs. moderate intensity condition.

Discussion

The primary finding of the present study is that local infusion of ascorbate augmented NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilation during high intensity exercise in the heat. These data suggest that oxidative stress associated with an accumulation of ascorbate-sensitive ROS contributes to the impairment in NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation observed in young adults during high intensity intermittent exercise.

Cutaneous vascular response

The contribution of NO to the cutaneous vascular response during whole-body heat stress associated with passive heating or exercise has been well documented (Kellogg et al. 1998; Holowatz et al. 2003; Holowatz et al. 2006a,b; Welch et al. 2009; Fujii et al. 2014; Johnson et al. 2014; McGinn et al. 2014a,b; McNamara et al. 2014). However, we recently demonstrated that NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation was reduced in young adults during exercise performed at a high intensity (Fujii et al. 2014). NO bioavailability can be impaired by oxidative stress associated with increases in the level of ROS such as superoxide (Radi et al. 1991; Squadrito & Pryor, 1998; Seifi-Skishahr et al. 2008; Mortensen & Lykkesfeldt, 2014). We propose that the mechanism mediating impaired NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation probably comprises increased ROS accumulation associated with high intensity exercise. This hypothesis is supported by our findings that local administration of the anti-oxidant ascorbate resulted in elevated CVC compared to the Control skin site throughout both exercise bouts in the high intensity exercise condition and this response was abolished when ascorbate was administered in combination with l-NAME. A ROS-mediated impairment in NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation during high intensity exercise is further supported by previous work demonstrating elevated levels of circulating malondialdehyde, a marker of oxidative stress, after 30 min of exercise performed at high (i.e. 75%  ) but not moderate intensity (i.e. 50%

) but not moderate intensity (i.e. 50%  ) (Goto et al. 2003); exercise intensities that are comparable to those employed in the present study (i.e. moderate intensity, 52 ± 6%

) (Goto et al. 2003); exercise intensities that are comparable to those employed in the present study (i.e. moderate intensity, 52 ± 6%  ; high intensity, 71 ± 8%

; high intensity, 71 ± 8%  ).

).

Recent studies utilizing dynamic exercise approaches demonstrate that NO contributes to the cutaneous vasodilatory response during exercise performed at 60%  (Welch et al. 2009; McNamara et al. 2014), despite the fact that elevated levels of circulating malondialdehyde have been reported at this exercise intensity, although to a lesser extent than exercise at 75%

(Welch et al. 2009; McNamara et al. 2014), despite the fact that elevated levels of circulating malondialdehyde have been reported at this exercise intensity, although to a lesser extent than exercise at 75%  (Seifi-Skishahr et al. 2008). Furthermore, NO-dependent vasodilatation has also been observed during short duration (i.e. 15 min), high intensity (i.e. 85%

(Seifi-Skishahr et al. 2008). Furthermore, NO-dependent vasodilatation has also been observed during short duration (i.e. 15 min), high intensity (i.e. 85%  ) exercise bouts performed in thermoneutral (McGinn et al. 2014a) and hot ambient conditions (35°C) (McGinn et al. 2014b). Initially, the observation of NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation in these studies appears to be inconsistent with a ROS-mediated impairment in NO bioavailability. However, the present study demonstrates several instances in which CVC was reduced relative to Control at the l-NAME and Ascorbate + l-NAME skin sites but simultaneously elevated compared to Control at the Ascorbate site. Altogether, these results suggest that a dynamic and time-dependent interaction exists between ROS and NO bioavailability during exercise. Thus, it is possible that the NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation observed in previous studies was partially but not entirely suppressed by ROS (Welch et al. 2009; McNamara et al. 2014), whereas the short duration high intensity exercise bout employed in our previous work (i.e. 15 min at 85%

) exercise bouts performed in thermoneutral (McGinn et al. 2014a) and hot ambient conditions (35°C) (McGinn et al. 2014b). Initially, the observation of NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation in these studies appears to be inconsistent with a ROS-mediated impairment in NO bioavailability. However, the present study demonstrates several instances in which CVC was reduced relative to Control at the l-NAME and Ascorbate + l-NAME skin sites but simultaneously elevated compared to Control at the Ascorbate site. Altogether, these results suggest that a dynamic and time-dependent interaction exists between ROS and NO bioavailability during exercise. Thus, it is possible that the NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation observed in previous studies was partially but not entirely suppressed by ROS (Welch et al. 2009; McNamara et al. 2014), whereas the short duration high intensity exercise bout employed in our previous work (i.e. 15 min at 85%  ) (McGinn et al. 2014a,b) may not have been sufficiently long to result in a marked increase in the level of oxidative stress. Thus, future studies are warranted to determine the precise influence of factors such as exercise intensity and duration, as well as the level of environmental heat stress, on ROS and NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation during exercise.

) (McGinn et al. 2014a,b) may not have been sufficiently long to result in a marked increase in the level of oxidative stress. Thus, future studies are warranted to determine the precise influence of factors such as exercise intensity and duration, as well as the level of environmental heat stress, on ROS and NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation during exercise.

Recovery from a bout of dynamic exercise is associated with an abrupt suppression in the heat loss responses such that cutaneous blood flow returns to baseline values within ∼20 min of the cessation of exercise (Kenny & Journeay, 2010; Kenny & Jay, 2013). This phenomenon is considered to be centrally mediated and associated with alterations in sensory receptor activation (e.g. baroreceptors) (Kenny & Journeay, 2010; Kenny & Jay, 2013). However, the results from the present study suggest that the accumulation of ROS during high intensity exercise may also influence the post-exercise recovery of the cutaneous vasodilatory response. Specifically, CVC was elevated at the Ascorbate relative to the Control skin site throughout the first recovery (20 min) and for the first 30 min of the second extended recovery period (40 min) in the high intensity condition. However, this response was abolished when l-NAME was infused simultaneously with ascorbate. The fact that CVC at the Control and Ascorbate sites was similar by the end of the second recovery period suggests that endogenous anti-oxidants were able to scavenge the ROS accumulated during exercise, restoring NO bioavailability and thereby NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation. Indeed, elevated endogenous anti-oxidant activity has been observed after 45 min of treadmill running at 75–80% of  in a hot environment (∼32°C) (Sureda et al. 2015), which would act to scavenge the accumulation of ROS produced during exercise.

in a hot environment (∼32°C) (Sureda et al. 2015), which would act to scavenge the accumulation of ROS produced during exercise.

Limitations

In the present study, direct indices of oxidative stress were not evaluated. Therefore, we are unable to determine whether the high intensity exercise bouts employed resulted in marked increases in ROS accumulation compared to the moderate intensity condition. However, Goto et al.(2003) observed increases in oxidative stress markers after exercise performed at 75% but not 50%  , exercise intensities that are comparable to the high (71 ± 8%

, exercise intensities that are comparable to the high (71 ± 8%  ) and moderate (52 ± 6%

) and moderate (52 ± 6%  ) conditions in the present study, respectively. Furthermore, Seifi-Skishahr et al. (2008) reported increases in oxidative stress after exercise at 75%

) conditions in the present study, respectively. Furthermore, Seifi-Skishahr et al. (2008) reported increases in oxidative stress after exercise at 75%  , whereas recent work by Sureda et al. (2015) demonstrated that intense exercise (75–85%

, whereas recent work by Sureda et al. (2015) demonstrated that intense exercise (75–85%  ) in a hot environment (∼32°C) results in greater elevations in oxidative stress relative to exercise performed in cooler conditions (∼12°C). In addition, two exercise bouts were employed in the present study, resulting in a greater total exercise time (i.e. 60 min), and presumably ROS accumulation, compared to the aforementioned studies. This notion is indirectly supported by our results for CVC, which demonstrate NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation during the early stages of the first but not second exercise bout. Our findings, taken together with those obtained in previous work (Goto et al. 2003; Seifi-Skishahr et al. 2008; Sureda et al. 2015), support the notion that the high intensity exercise bouts in the present study resulted in marked increases in oxidative stress and comparatively lower levels of ROS accumulation in the moderate condition.

) in a hot environment (∼32°C) results in greater elevations in oxidative stress relative to exercise performed in cooler conditions (∼12°C). In addition, two exercise bouts were employed in the present study, resulting in a greater total exercise time (i.e. 60 min), and presumably ROS accumulation, compared to the aforementioned studies. This notion is indirectly supported by our results for CVC, which demonstrate NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation during the early stages of the first but not second exercise bout. Our findings, taken together with those obtained in previous work (Goto et al. 2003; Seifi-Skishahr et al. 2008; Sureda et al. 2015), support the notion that the high intensity exercise bouts in the present study resulted in marked increases in oxidative stress and comparatively lower levels of ROS accumulation in the moderate condition.

Perspectives and significance

During whole-body heat stress associated with exercise and/or exposure to a hot environment, increases in skin temperature secondary to elevations in cutaneous blood flow are crucial to the modulation of heat exchange with the environment and, consequently, the regulation of core body temperature. The findings of the present study demonstrate that an accumulation of ROS can influence the cutaneous vasodilatory response during high intensity exercise in the heat. In addition to high intensity exercise, ageing (Finkel & Holbrook, 2000; Holowatz et al. 2006a) and chronic pathophysiological conditions such as diabetes (Brownlee, 2001; Maddux et al. 2001; Hoeldtke et al. 2011) are associated with elevations in oxidative stress, as well as impairments in whole-body heat loss (Kenny et al. 2013; Larose et al. 2013; Larose et al. 2014). Age-related elevations in oxidative stress have been associated with reductions in the cutaneous vasodilatory response to passive whole-body heating, although the mechanisms of attenuated cutaneous blood flow during exercise in the aged have not been systematically explored. Furthermore, the interactions of oxidative stress, NO and heat loss responses in individuals with diabetes have not been assessed. Therefore, future work should aim to determine the role of oxidative stress in the mechanisms underlying the impairments in cutaneous vasodilatation observed in older adults and those with chronic health conditions that place these individuals at greater risk of heat-related illness and injury during thermal challenges.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilatation is impaired by oxidative stress associated with an accumulation of ascorbate-sensitive ROS induced by high intensity exercise performed in the heat.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate all of the volunteers for taking time to participate in the present study and Martin Poirier for his technical assistance. We would like to thank Mr Michael Sabino of Can-Trol Environmental Systems Limited (Markham, ON, Canada) for his support, as well as Ryan McGinn and Pegah Akbari for their assistance with the study.

Glossary

- CVC

cutaneous vascular conductance

- NO

nitric oxide

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

RDM, NF and GPK conceived and designed the experiments. RDM, NF, GP and JCL contributed to the data collection. RDM performed the data analysis. RDM, NF, LMA, ADF and GPK interpreted the experimental results. RDM prepared the figures. RDM drafted the manuscript. RDM, NF, LMA, GP, JCL, ADF and GPK edited and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication. All experiments took place at the Human and Environmental Physiology Research Unit located at the University of Ottawa.

Funding

The present study was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Discovery Grant (RGPIN-06313-2014), Discovery Grants Program – Accelerator Supplements (RGPAS-462252-2014) and by a Leaders Opportunity Fund from the Canada Foundation for Innovation (funds held by G. P. Kenny). R. D. Meade was supported by a Queen Elizabeth II Graduate Scholarship in Science and Technology. N. Fujii was supported by the Human and Environmental Physiology Research Unit. G. Paull was supported by an Ontario Graduate Scholarship.

References

- Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414:813–820. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunt VE, Fujii N. Minson CT. No independent, but an interactive, role of calcium-activated potassium channels in human cutaneous active vasodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2013;115:1290–1296. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00358.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois D. Dubois EF. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight are known. Arch Intern Med. 1916;17:863–871. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T. Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii N, McGinn R, Stapleton JM, Paull G, Meade RD. Kenny GP. Evidence for cyclooxygenase-dependent sweating in young males during intermittent exercise in the heat. J Physiol. 2014;592:5327–5339. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.280651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii N, Meade RD, Paull G, McGinn R, Foudil-Bey I, Akbari P. Kenny GP. Can intradermal administration of angiotensin II influence human heat loss responses during whole body heat stress? J Appl Physiol (1985) 2015;118:1145–1153. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00025.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon D, Jay O. Kenny GP. The evaporative requirement for heat balance determines whole-body sweat rate during exercise under conditions permitting full evaporation. J Physiol. 2013;591:2925–2935. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.248823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes EC, Silva AN. de Oliveira MR. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the beneficial roles of exercise-induced production of reactive species. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2012;2012:756132. doi: 10.1155/2012/756132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto C, Higashi Y, Kimura M, Noma K, Hara K, Nakagawa K, Kawamura M, Chayama K, Yoshizumi M. Nara I. Effect of different intensities of exercise on endothelium-dependent vasodilation in humans: role of endothelium-dependent nitric oxide and oxidative stress. Circulation. 2003;108:530–535. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080893.55729.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JD. Dubois EF. The technic of measuring radiation and convection. J Nutr. 1938;15:461–475. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges GJ, Chiu C, Kosiba WA, Zhao K. Johnson JM. The effect of microdialysis needle trauma on cutaneous vascular responses in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2009;106:1112–1118. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91508.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeldtke RD, Bryner KD. VanDyke K. Oxidative stress and autonomic nerve function in early type 1 diabetes. Clin Auton Res. 2011;21:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s10286-010-0084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holowatz LA. Ascorbic acid: what do we really NO? J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011;111:1542–1543. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01187.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holowatz LA, Houghton BL, Wong BJ, Wilkins BW, Harding AW, Kenney WL. Minson CT. Nitric oxide and attenuated reflex cutaneous vasodilation in aged skin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1662–H1667. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00871.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holowatz LA, Thompson CS. Kenney WL. Acute ascorbate supplementation alone or combined with arginase inhibition augments reflex cutaneous vasodilation in aged human skin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2965–H2970. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00648.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holowatz LA, Thompson CS. Kenney WL. L-Arginine supplementation or arginase inhibition augments reflex cutaneous vasodilatation in aged human skin. J Physiol. 2006;574:573–581. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.108993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JM, Minson CT. Kellogg DL., Jr Cutaneous vasodilator and vasoconstrictor mechanisms in temperature regulation. Compr Physiol. 2014;4:33–89. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg DL, Jr, Crandall CG, Liu Y, Charkoudian N. Johnson JM. Nitric oxide and cutaneous active vasodilation during heat stress in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1998;85:824–829. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.3.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny GP. Jay O. Thermometry, calorimetry, and mean body temperature during heat stress. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:1689–1719. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny GP. Journeay WS. Human thermoregulation: separating thermal and nonthermal effects on heat loss. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2010;15:259–290. doi: 10.2741/3620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny GP, Stapleton JM, Yardley JE, Boulay P. Sigal RJ. Older adults with type 2 diabetes store more heat during exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:1906–1914. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182940836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larose J, Boulay P, Sigal RJ, Wright HE. Kenny GP. Age-related decrements in heat dissipation during physical activity occur as early as the age of 40. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larose J, Boulay P, Wright-Beatty HE, Sigal RJ, Hardcastle S. Kenny GP. Age-related differences in heat loss capacity occur under both dry and humid heat stress conditions. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2014;117:69–79. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00123.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovlin R, Cottle W, Pyke I, Kavanagh M. Belcastro AN. Are indices of free radical damage related to exercise intensity. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1987;56:313–316. doi: 10.1007/BF00690898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddux BA, See W, Lawrence JC, Jr, Goldfine AL, Goldfine ID. Evans JL. Protection against oxidative stress-induced insulin resistance in rat L6 muscle cells by mircomolar concentrations of alpha-lipoic acid. Diabetes. 2001;50:404–410. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinn R, Fujii N, Swift B, Lamarche DT. Kenny GP. Adenosine receptor inhibition attenuates the suppression of postexercise cutaneous blood flow. J Physiol. 2014;592:2667–2678. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.274068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinn R, Paull G, Meade RD, Fujii N. Kenny GP. Mechanisms underlying the postexercise baroreceptor-mediated suppression of heat loss. Physiol Rep. 2014;2:e12168. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara TC, Keen JT, Simmons GH, Alexander LM. Wong BJ. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase mediates the nitric oxide component of reflex cutaneous vasodilatation during dynamic exercise in humans. J Physiol. 2014;592:5317–5326. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.272898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen A. Lykkesfeldt J. Does vitamin C enhance nitric oxide bioavailability in a tetrahydrobiopterin-dependent manner? In vitro, in vivo and clinical studies. Nitric Oxide. 2014;36:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radi R, Beckman JS, Bush KM. Freeman BA. Peroxynitrite-induced membrane lipid peroxidation: the cytotoxic potential of superoxide and nitric oxide. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;288:481–487. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawka MN, Burke LM, Eichner ER, Maughan RJ, Montain SJ. Stachenfeld NS. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and fluid replacement. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:377–390. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31802ca597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifi-Skishahr F, Siahkohian M. Nakhostin-Roohi B. Influence of aerobic exercise at high and moderate intensities on lipid peroxidation in untrained men. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2008;48:515–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siri WE. The gross composition of the body. Adv Biol Med Phys. 1956;4:239–280. doi: 10.1016/b978-1-4832-3110-5.50011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squadrito GL. Pryor WA. Oxidative chemistry of nitric oxide: the roles of superoxide, peroxynitrite, and carbon dioxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;25:392–403. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanhewicz AE, Bruning RS, Smith CJ, Kenney WL. Holowatz LA. Local tetrahydrobiopterin administration augments reflex cutaneous vasodilation through nitric oxide-dependent mechanisms in aged human skin. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2012;112:791–797. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01257.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton JM, Fujii N, Carter M. Kenny GP. Diminished nitric oxide-dependent sweating in older males during intermittent exercise in the heat. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:921–932. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.077644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JM, Taneja I, Raghunath N, Clarke D. Medow MS. Intradermal angiotensin II administration attenuates the local cutaneous vasodilator heating response. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H327–H334. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00126.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sureda A, Mestre-Alfaro A, Banquells M, Riera J, Drobnic F, Camps J, Joven J, Tur JA. Pons A. Exercise in a hot environment influences plasma anti-inflammatory and antioxidant status in well-trained athletes. J Therm Biol. 2015;47:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift B, McGinn R, Gagnon D, Crandall CG. Kenny GP. Adenosine receptor inhibition attenuates the decrease in cutaneous vascular conductance during whole-body cooling from hyperthermia. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:196–204. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.075200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch G, Foote KM, Hansen C. Mack GW. Nonselective NOS inhibition blunts the sweat response to exercise in a warm environment. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2009;106:796–803. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90809.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong BJ. Minson CT. Neurokinin-1 receptor desensitization attenuates cutaneous active vasodilatation in humans. J Physiol. 2006;577:1043–1051. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.112508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]