Abstract

Background/Aims

Male and female rats differ in their ability to utilize spinal endomorphin 2 (EM2; the predominant mu-opioid receptor ligand in spinal cord) and in the mechanisms that underlie spinal EM2 analgesic responsiveness. We investigated the relevance of spinal estrogen receptors (ERs) to the in vivo regulation of spinal EM2 release.

Methods

ER antagonists were administered directly to the lumbosacral spinal cord of male and female rats, intrathecal perfusate was collected, and resulting changes in EM2 release were quantified using a plate-based radioimmunoassay.

Results

Intrathecal application of an antagonist of either estrogen receptor-α (ERα) or the ER GPR30 failed to alter spinal EM2 release. Strikingly, however, the concomitant blockade of ERα and GPR30 enhanced spinal EM2 release. This effect was sexually dimorphic, being absent in males. Furthermore, the magnitude of the enhancement of spinal EM2 release in females was dependent upon estrous cycle stage, suggesting a relationship with circulating levels of 17β-estradiol. The rapid onset of enhanced EM2 release following intrathecal application of ERα/GPR30 antagonists (within 30–40 min) suggests mediation via ERs in the plasma membrane, not the nucleus. Notably, both ovarian and spinally synthesized estrogens are essential for membrane ER regulation of spinal EM2 release.

Conclusion

These findings underscore the importance of estrogens for the regulation of spinal EM2 activity and, by extension, endogenous spinal EM2 antinoci-ception in females. Components of the spinal estrogenic mechanism(s) that suppress EM2 release could represent novel drug targets for improving utilization of endogenous spinal EM2, and thereby pain management in women.

Keywords: Membrane estrogen receptors, Aromatase, Estrous cycle, Mu-opioid receptors

Introduction

Clinical and epidemiological studies have repeatedly demonstrated that women experience greater severity and frequency of chronic pain syndromes than men [1, 2]. Additionally, pain sensitivity changes over the course of the menstrual cycle in women [3] and the estrous cycle in rats [4]. Although the underlying mechanisms for these sex- and cycle-dependent differences are not well characterized, studies in animal models suggest that pain sensitivity is regulated by the endogenous opioids as well as sex steroids [5]. For example, the analgesia produced by opioid drugs differs significantly between males and females [6] and over the course of the estrous cycle [7]. Furthermore, the administration of exogenous estrogens increases pain sensitivity in male rats [8], and eliminating endogenous testosterone via gonadectomy prevents male rats from habituating to repetitive painful stimuli [9].

Since levels of circulating 17β-estradiol (E2), the predominant estrogen in adults of both sexes, differ considerably between males and females and over the course of the menstrual/estrous cycle [10–15], many studies have examined the relevance of endogenous estrogens (estrone, E2, and estriol) to sex- and cycle-dependent differences in pain behavior [for review, see 16]. The ovaries synthesize the vast majority of circulating estrogens, which can rapidly penetrate the blood-brain barrier to activate estrogen receptors (ERs) in the central nervous system (CNS) [17]. Additionally, estrogens are synthesized in situ by CNS neurons where they are postulated to act locally as neuromodulators and/or neurotransmitters [18, 19].

Estrogens can exert rapid regulatory effects on antinociceptive systems via membrane ERs (mERs) [20]. For instance, E2 inhibits ATP-induced (pronociceptive) calcium currents in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons [21] and augments the dimerization of spinal mu-opioid receptor (MOR) with kappa-opioid receptor (KOR) in females [22], both via mERs. Notably, the nongenomic effects of activating mERs are observed within the same time frame as those of G protein-coupled receptors (seconds to minutes) – much more rapidly than the time required for the effects of activating nuclear ERs to be manifest. At least three subtypes of mER have been identified: mERα and mERβ, derived from the translocation of their nuclear counterparts, and GPR30 (aka GPER), which is purported to be G protein-coupled [23, 24]. mERs can partner with metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) [25–27] and can utilize virtually all established membrane-initiated signaling cascades [for review, see 28].

Endomorphin 1 (Tyr-Pro-Trp-Phe-NH2) and endomorphin 2 (Tyr-Pro-Phe-Phe-NH2; EM1 and EM2, respectively) are endogenous opioids with much higher selectivities and affinities for MOR than for KOR or delta-opioid receptor [29, 30]. Intracerebroventricular or intrathecal application of EM1 or EM2 generates strong MOR-mediated analgesia [31, 32]. EM2 is the predominant EM expressed in the spinal cord [33], and utilization of the spinal MOR/EM2 system is sexually dimorphic: MOR activation produces greater antinociception in males than females [34–43], and basal/K+-evoked EM2 release is greater from spinal tissue of male than female rats [44].

The functional state of the MOR/EM2 system fluctuates naturally over the course of the estrous cycle. Our laboratory recently demonstrated that spinal EM2 antinociception is not only greater in male rats than diestrous female rats, but also greater in proestrous than diestrous females [45]. We therefore hypothesized that regulation of spinal EM2 release is also sex and cycle dependent. Given that peripheral estrogen levels depend upon sex and estrous stage [10], and that estrogens regulate antinociceptive signaling via mERs [21, 22], we further hypothesized that spinal EM2 release is regulated by estrogens via mERs. In the present study, these hypotheses were tested by comparing the effects of spinal ER blockade on spinal EM2 release among male and female rats at different stages of the estrous cycle. Results revealed sexually dimorphic and estrous cycle-dependent suppression of EM2 release derived from both peripheral and central estrogens. The female-specific suppression of EM2 release suggests that females cannot utilize spinal MOR/EM2 antinociceptive signaling as effectively as males, possibly contributing to women’s increased vulnerability to chronic pain syndromes.

Materials and Methods

Animals

We employed Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Kingston, N.Y., USA; 250–300 g), which were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. All experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Determination of Stage of Estrous Cycle

We determined estrous cycle stage via histology of vaginal smears. A predominance of round nucleated cells, large nonnucleated cells, or small leukocytes indicated proestrus, estrus, or diestrus, respectively. Rats were used in the early part of proestrus, when E2 levels are highest [10, 14, 15], and on day 2 of diestrus, which lasts for 3 days, to avoid overlap with adjacent stages.

Ovariectomy

To assess the activational effects of ovarian estrogens on spinal EM2 release, adult female rats were ovariectomized 8 days prior to their utilization. Animals were pretreated with atropine (0.85 mg/kg i.p.; IUX Animal Health Inc., St. Joseph, Mo., USA) and anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg i.p.; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, Ill., USA) before removal of the ovaries [46].

Implantation of Intrathecal Cannulas and in vivo Perfusion of the Spinal Intrathecal Space

We implanted two PE-10 catheters (8.25-cm inflow and 6.75-cm outflow; Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lanes, N.J., USA) into the subarachnoid space as described previously [47]. Briefly, we anesthetized animals as described above and inserted two cannulas through the atlanto-occipital membrane into the lumbar spinal subarachnoid space. The cephalic portions of the catheters were externalized through the skin on the dorsal side of the neck, immediately after which the intrathecal space was perfused (5 µl/min) with Krebs-Ringer buffer prewarmed to 37 °C. To prevent EM2 degradation, the buffer contained protease inhibitors phenanthroline (1 mm; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo., USA) and actinonin (100 µm; AG Scientific, San Diego, Calif., USA), and the outflow tubing was placed on ice. We equilibrated the intrathecal space with the perfusion medium for 10 min prior to collecting four 10-min perfusate samples from each animal to measure EM2 release: two before and two after intrathecal drug treatment. To inhibit spinal aromatase, we administered intrathecal fadrozole immediately after the 10-min equilibration period.

Intrathecal Administration of Drugs

We delivered drugs to the subarachnoid space via the inflow intrathecal cannula over a 60-second period. Each drug was administered in 2.5–5 µl vehicle, followed by 10 µl buffer to flush the cannula. EM2 release was quantified at various intervals thereafter and compared against predrug values. ER antagonists and the glutamate receptor antagonist YM-298198 were obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK); the aromatase inhibitor fadrozole was from Sigma-Aldrich.

EM2 Competitive Radioimmunoassay

The content of EM2 in intrathecal perfusate was quantified using a competitive radioimmunoassay described previously [44] that employed a highly selective anti-EM2 antibody (generously supplied by Dr. James Zadina, Tulane University) and 125I-labeled EM2 (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Burlingame, Calif., USA) as tracer. Nonspecific adherence to the assay tube was minimized using bovine serum albumin (0.1%; Sigma-Aldrich). We counted assay plates using a MicroBeta plate reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, Mass., USA) and quantified unknown values from a standard curve generated with each assay using the forecast function in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Wash., USA).

Membrane Preparation and Immunoprecipitation

Spinal cords from 3 proestrous rats were collected and processed individually in parallel. Each was homogenized in 5 ml buffer containing 20 mm HEPES, 5 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 2 mm DTT, 10% sucrose, and protease inhibitors aprotinin at 2 µg/ml, leupeptin at 3.2 µg/ml, phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride at 20 µg/ml, and cOmplete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets (Roche, Indianapolis, Ind., USA) at 1 tablet/50 ml, pH 7.4, using glass Teflon homogenizers. Following a 10-min 1,500 g centrifugation at 4 °C, the pellet was washed in another 5 ml of homogenization buffer and subjected to a 10-min 2,500 g centrifugation at 4°C. The supernatants from both centrifugations were combined and subjected to 31,000 g centrifugation for 40 min at 4°C. The resulting membrane fraction pellet was resuspended in the homogenization buffer without sucrose and stored in aliquots at –80 ° C until needed.

For immunoprecipitation, membranes were solubilized in two volumes of solubilization buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet-P40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, and protease inhibitors as above, pH 7.4, with agitation for 60 min at 4°C, centrifuged at 16,000 g for 15 min at 4°C, and the clear supernatants containing solubilized membrane fraction were used for Bradford Protein Assay. ERα was immunoprecipitated using 15 µl of mouse monoclonal affinity purified antibody (raised against amino acids 495–595; Santa Cruz, Dallas, Tex., USA) per 600 µg of each sample. Following a 60-min gentle agitation at 4 °C, samples were combined with prewashed protein A agarose beads (60 µl slurry/sample; Roche) and immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C. The beads were then washed using a buffer containing 25 mm Tris-HCl, 5 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton-X-100, and protease inhibitors as above, pH 7.4. Immunoprecipitates were eluted with heat (15 min at 86 ° C) in 30 µl NuPAGE lithium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer containing 1× NuPAGE reducing agent (Invitrogen, Norwalk, Conn., USA). Samples were separated on 4–12% Bis-Tris Mini Gels (Invitrogen), electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose membrane, and Western blotted. GPR30 was visualized using a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against an internal region of GPR30 (Santa Cruz). The antibodies used for immunoprecipitation and subsequent Western blotting were raised in different species to avoid cross-recognition by secondary antibodies. The signal was developed using SuperSignal West Dura enhanced chemiluminescence horseradish peroxidase substrate (Life Technologies, Norwalk, Conn., USA) and the chemiluminescence captured using a G:Box CCD Camera (Syngene, Cambridge, UK). Specificity of the GPR30 Western signal was verified by >80% reduction of signal when preadsorbed antibody flow-through was used. For preadsorption, the peptide that served as the antigen for generation of the primary antibody was coupled to Affi-Gel 10 slurry (Pierce, Rockford, Ill., USA), and the primary antibody pre-adsorbed in 1× Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.4, at room temperature for 2 h (twice) under gentle agitation. Following that incubation, the flow-through was collected and used to probe one of two identical nitrocellulose membrane strips for GPR30 immunoblotting. The other strip was immunoblotted with nonpreadsorbed anti-GPR30 antibody. Signal intensity was quantified using Genetools software (Syngene).

Data Analysis

Student’s t test and one-way ANOVA were used to compare basal EM2 release between groups. One-way repeated measures ANOVA was used to determine the effect of treatment at multiple time points after intrathecal administration of drugs within each group. Tukey’s test was used to identify specific time points at which significant effects were manifest. Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze interactions between stage of estrous cycle and time after treatment. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Results

Basal Spinal EM2 Release

The basal rate of spinal EM2 release per 10-min period did not vary over the 90 min of intrathecal perfusion, nor did it differ between males (3.88 ± 0.18 fmol; n = 5) and naïve females (4.70 ± 0.37 fmol; n = 24, collapsed across estrous cycle stages; t27 = 1.00; p = 0.328). Among naïve females, however, one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of estrous stage on basal EM2 release (F2, 21 = 5.09; p = 0.016): EM2 release was significantly higher in estrus (6.85 ± 0.79 fmol; n = 4) than in either proestrus (4.57 ± 0.33 fmol; n = 11) or diestrus (3.90 ± 0.66 fmol; n = 9). Putative differences in basal spinal EM2 release in proestrous versus diestrous rats could have been obscured by variations in EM2 release between subjects, which may be greater than variations between proestrous and diestrous stages of the estrous cycle.

Regulation of Spinal EM2 Release by ERs Is Sexually Dimorphic and Dependent on Stage of Estrous Cycle

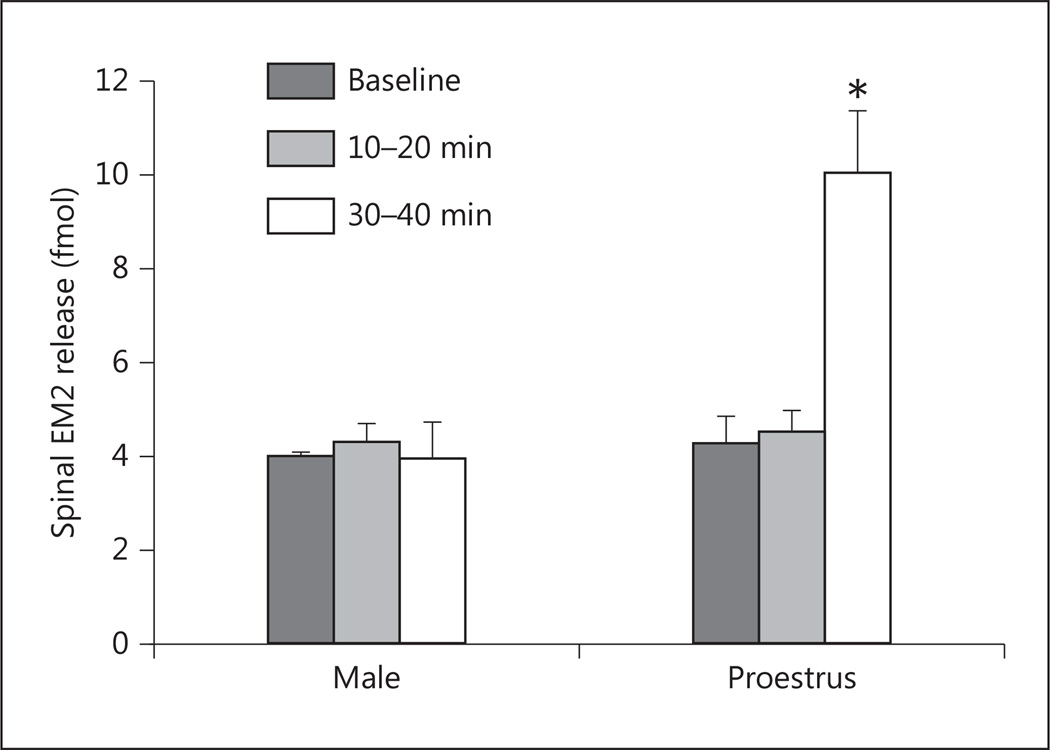

Initially, we determined the effects of individual antagonists for ERα, ERβ, and GPR30 (MPP, PHTPP, and G15, respectively) on spinal EM2 release in proestrous females. Based on the dose-effect relationship of these ER antagonists to alter characteristics of spinal morphine analgesia [22], 10 nmol was selected for further study. Oneway repeated measures ANOVA revealed that the magnitude of spinal EM2 release was unaltered by intrathecal blockade of either ERα (F2, 6 = 1.11; p = 0.389, n = 4), ERβ (F2, 8 = 1.79; p = 0.227, n = 5), or GPR30 (F2, 8 = 0.17; p = 0.844, n = 5). Since multiple mER types have been reported to act cooperatively [22, 28, 48–50], we also determined the effects of combinations of ER antagonists. In contrast to the individual blockade of ERα and GPR30, their concomitant blockade (fig. 1) substantially augmented spinal EM2 release in proestrous females (F2, 6 = 16.50; p = 0.004, n = 4): EM2 release increased from 4.16 ± 0.70 to 9.95 ± 1.43 fmol 30–40 min after treatment (p < 0.01). The rapid onset of effects of ERα/GPR30 blockade (30 min) suggests that mERs, rather than nuclear ERs, modulate spinal EM2 release. Strikingly, in contrast to proestrous females, combined ERα/GPR30 blockade failed to alter EM2 release in males (F2, 8 = 0.14; p = 0.868, n = 5).

Fig. 1.

Blockade of ERα/GPR30 disinhibits spinal EM2 release in proestrous females but not males. The spinal intrathecal space was perfused at 5 µl/min using the push-pull method as described in Materials and Methods. MPP (ERα antagonist) and G15 (GPR30 antagonist) were administered via the inflow spinal cannula. The EM2 content of perfusate was quantified using a competitive radioimmunoassay. Vertical bars represent spinal EM2 release at three time points: baseline, 10–20 min after drug treatment, and 30–40 min after drug treatment. Data are expressed as fmol EM2 per 10-min period. * p < 0.01 for EM2 release in proestrous females before vs. 30–40 min after intrathecal administration of MPP and G15 (n = 4–5).

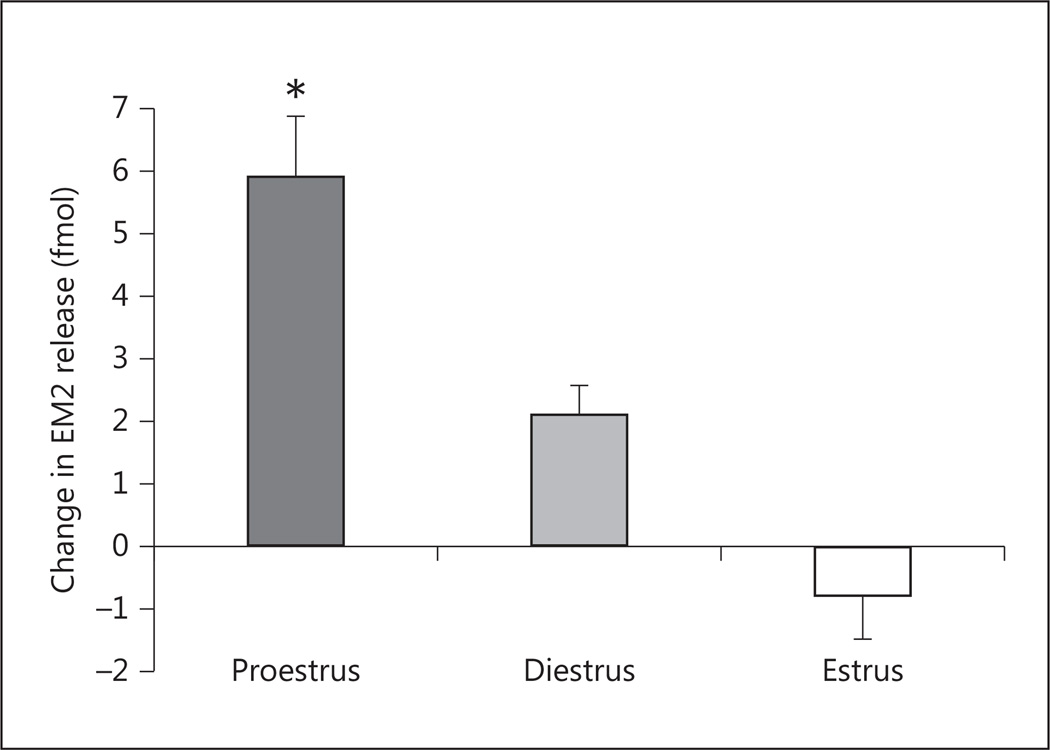

To assess whether changes in peripheral estrogen levels over the course of the estrous cycle influence mER regulation of EM2 release, we compared the effect of blocking spinal ERα/GPR30 on spinal EM2 release during proestrus with that observed during diestrus and estrus in females. Two-way ANOVA revealed the main effects of treatment (p < 0.001) and estrous stage (p = 0.044), as well as a significant treatment × estrous stage interaction (p < 0.001). At 30–40 min after treatment, the increase in EM2 release (fig. 2) was largest in proestrus (139% above basal release), intermediate in diestrus (67%), and not detectable in estrus.

Fig. 2.

The magnitude of change in EM2 release following spinal ERα/GPR30 blockade is stage of estrous cycle dependent. One-way ANOVA showed a main effect of estrous stage on change in spinal EM2 release (F2, 10 = 14.73; p = 0.001). Post hoc tests revealed that the magnitude of enhanced EM2 release was significantly greater in proestrus vs. diestrus or estrus (* p < 0.05 for both comparisons). Data are expressed as fmol EM2 above basal release 30–40 min after intrathecal application of ERα/GPR30 antagonists (n = 4–5).

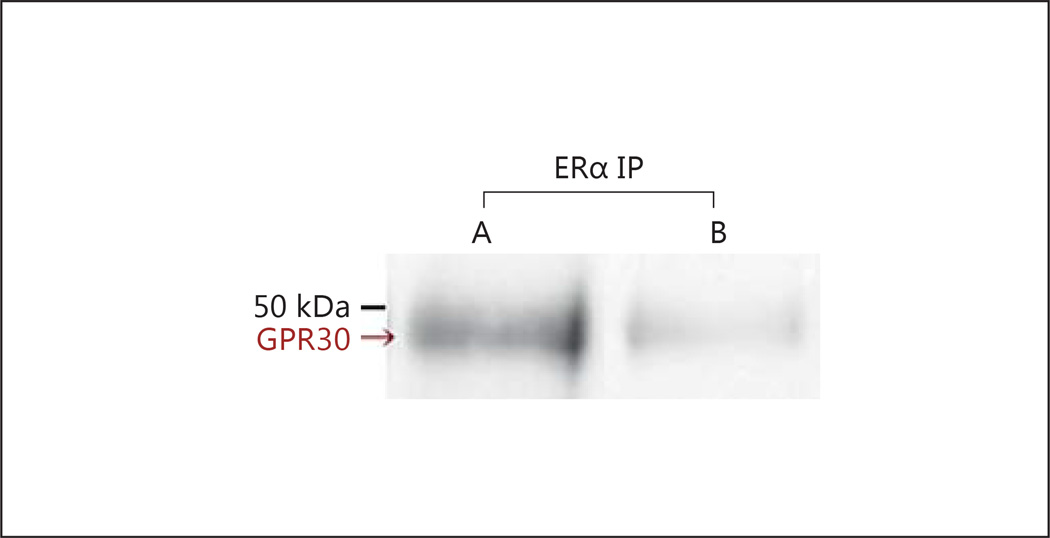

mERα and GPR30 Are Present in a Common Complex

Collaboration between mERα and GPR30 in regulating spinal EM2 release prompted us to investigate their physical association. This was accomplished by determining the presence of GPR30 in immunoprecipitate obtained with anti-ERα antibody. GPR30 Western analyses of spinal membranes immunoprecipitated with anti-ERα antibody revealed a ≈ 50-kDa signal (fig. 3, lane A), which was substantially reduced (>80%) when ERα immunoprecipitate was Western blotted using preadsorbed anti-GPR30 antibody (fig. 3, lane B). The molecular mass of this signal is comparable to that previously reported for rat spinal GPR30, also assessed via Western blotting [51]. While the observed co-immunoprecipitation does not unequivocally indicate a direct physical association between ERα and GPR30, it does indicate that they coexist within a common complex.

Fig. 3.

ERα and GPR30 co-immunoprecipitate. Lane A: ERα immunoprecipitate contains GPR30 immunoreactivity. The specificity of the ≈50-kDa GPR30 Western signal is shown in lane B by the >80% reduction in signal intensity when the same immunoprecipitated sample is Western blotted using preadsorbed anti-GPR30 antibody. Data shown for one of three replications.

Enhancement of Spinal EM2 Release by ERα/GPR30 Blockade Is mGluR1 Independent

Some of the signaling pathways recruited by mERs involve activation of mGlurR1 [25–27]. To assess potential contributions of mGluR1 to the modulation of EM2 release via mERα/GPR30, we determined the effect of the highly selective mGluR1 antagonist YM-298198 (26 nmol) [52–55] on spinal EM2 release in proestrous and diestrous females. Intrathecal application of YM-298198 did not alter EM2 release during either proestrus (F2, 12 = 1.23; p = 0.326, n = 7) or diestrus (F2, 6 = 0.08; p = 0.920, n = 4).

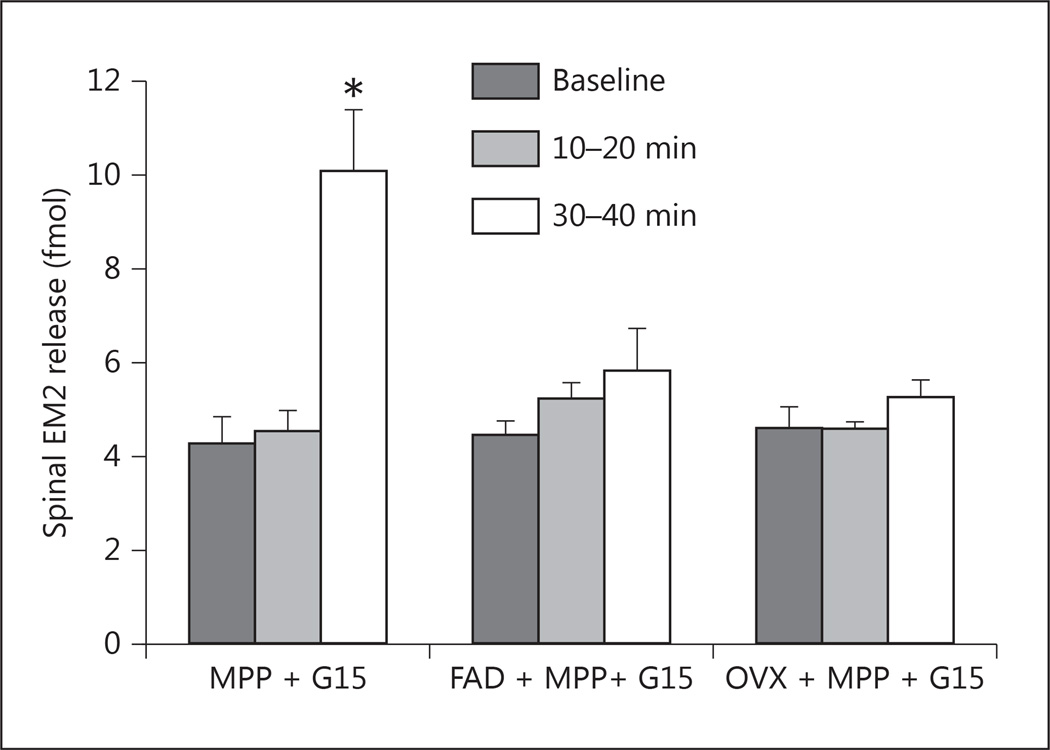

Ovariectomy or Inhibition of Spinal Aromatase Abolishes Enhancement of Spinal EM2 Release following ERα/GPR30 Blockade

Spinal ERs can be activated by locally synthesized estrogens and/or estrogens synthesized in the periphery (e.g. ovaries). To determine whether spinal ER-mediated modulation of EM2 release requires locally synthesized and/or ovarian estrogens, we determined the effect of the intrathecally applied aromatase inhibitor fadrozole (2.5 nmol) or ovariectomy on the modulation of EM2 release by ERα/GPR30. For the latter, female rats were ovariectomized during either proestrus or diestrus, and the effect of ERα/GPR30 blockade was determined 8 days (the equivalent of two full estrous cycles) after ovariectomy. Strikingly, the enhancement of spinal EM2 release by concomitant blockade of ERα and GPR30 was eliminated by either intrathecal fadrozole 1-hour pretreatment (F2, 6 = 0.84; p = 0.477, n = 4) or ovariectomy (F2, 10 = 1.01; p = 0.399, n = 6; fig. 4). Spinal EM2 release 30–40 min after ERα/GPR30 blockade did not differ between proestrous females pretreated with intrathecal fadrozole (5.68 ± 1.05 fmol) and ovariectomized females (5.13 ± 0.50 fmol; t8 = 0.53, p = 0.611). Additionally, effects of ovariectomy were equivalent whether ovaries were removed during proestrus (F2, 4 = 2.08; p = 0.241, n = 3) or diestrus (F2, 4 = 0.98; p = 0.452, n = 3). These data demonstrate that both central and peripheral estrogens are required for the modulation of spinal EM2 release via spinal ERs.

Fig. 4.

Disinhibition of EM2 release following intrathecal MPP (ERα antagonist) and G15 (GPR30 antagonist) is abolished by intrathecal pretreatment (1 h) with the aromatase inhibitor fadrozole (FAD) in proestrous females, or by bilateral ovariectomy (OVX). Vertical bars represent spinal EM2 release (fmol per 10 min) at three time points: baseline, 10–20 min after drug treatment (ERα/GPR30 blockade), and 30–40 min after drug treatment. * p < 0.01 for EM2 release in proestrous females before vs. 30–40 min after intrathecal administration of MPP and G15 (n = 4–6).

Discussion

In this study, the negative estrogenic regulation of spinal EM2 release is reflected by the enhancement of EM2 release following blockade of spinal mERs. Our findings demonstrate that this regulation is dynamic, fluctuating in magnitude over the estrous cycle. Specific findings include: (1) spinal mERα and GPR30 act in a cooperative fashion to negatively modulate spinal EM2 release; (2) the magnitude of disinhibition of EM2 release following ERα/GPR30 blockade varies across the estrous cycle; (3) modulation of spinal EM2 release via ERα and GPR30 is sexually dimorphic (it is not observed in males); (4) spinal ERα and GPR30 are present in a common complex; (5) regulation of spinal EM2 release via mERs requires both peripherally and spinally synthesized estrogens. It remains to be determined whether spinal mERβ also acts cooperatively with other mERs to regulate spinal EM2 release.

Estrogens Suppress EM2 Release via mERs

The cycle-dependent enhancement (disinhibition) of EM2 release produced by blockade of ERα/GPR30 indicates that under physiological conditions, estrogens tonically suppress EM2 release in proestrous and diestrous females. The rapid onset (30–40 min) of this enhancement is consistent with mediation via ERs in the plasma membrane [56–59]. Previous studies have demonstrated analogous rapid regulation of antinociceptive signaling by mERs. For example, estrogenic suppression of pronociceptive calcium currents in DRG neurons is reversed within 5 min of ER blockade [21], and KOR-dependent spinal morphine antinociception in proestrous females is eliminated within 15 min of spinal ER blockade [22]. In contrast, estrogenic signaling via nuclear receptors requires hours to days for effects to be manifest. For instance, administration of exogenous E2 to ovariectomized female rats increases KOR gene expression after 48 h [60], and ovariectomy induces mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in females after 28 days [61]. Some immediateearly genes, including those regulated by nuclear ERs, are transcribed within 20 min [62–64]. However, it is highly unlikely that the effects of spinal ER blockade on EM2 release involve immediate-early transcription because transcriptional effects require additional time for trans gene activation and protein synthesis. Furthermore, if the effects of ER blockade were genomic, ER antagonists would be expected to block transcription (not activate it). This would require depletion of existing protein pools, not likely to be manifest in the 30–40 min within which spinal EM2 release was enhanced. Importantly, modulation of spinal EM2 release by mERα/GPR30 does not preclude contributions from nuclear ERs, particularly since there is considerable cross-talk and convergence between mERs and nuclear ERs (e.g. mER-activated signaling cascades can potentiate nuclear transcription, thus impacting sustained effects of estrogens as well as their nongenomic actions) [65, 66].

mERα and GPR30 Operate in Tandem to Suppress EM2 Release

The nature of GPR30 functionality as an ER is somewhat ambiguous. Some studies are consistent with GPR30 acting as a stand-alone ER [67–71], while others suggest that GPR30 acts as an accessory protein, collaborating with mERα/mERβ and/or other membrane proteins [72–74, for review, see 28]. GPR30 has recently been shown to bind to postsynaptic density-95 (aka PSD-95) [75], a membrane scaffolding protein. This increases plasma membrane localization of GPR30, which influences the membrane-initiated signaling cascades it initiates as well as its interactions with other membrane receptors [76–79]. Importantly, receptor and modulator functionalities are not mutually exclusive; GPR30 function appears to be dependent on cellular context and the specific agonist used [50].

In the current study, individual blockade of ERα and GPR30 did not alter EM2 release, but their combined blockade did. This indicates that both mERα and GPR30 act in concert to suppress spinal EM2 release. The present demonstration of cooperative signaling by mERα and GPR30 is consistent with earlier reports of their co-expression by neurons of the spinal dorsal horn [22] and their cooperative effects on gene transcription [48] and formation of spinal MOR/KOR heterodimers [22]. In these reports, ERα and GPR30 functioned interdependently.

The requirement for concomitant blockade of GPR30 and ERα suggests that their contributions to clamping spinal EM2 release result from neither their interdependent actions nor the modulation of ERα by GPR30. Instead, GPR30 and ERα appear to act in parallel to independently negatively modulate spinal EM2 release, each one being sufficient to mediate the observed clamp on EM2 utilization. This redundancy would ensure reliability of fine-tuning spinal EM2 synaptic activity. The presence of both GPR30 and ERα in the same complex (fig. 3) could provide a cellular/molecular context for ensuring optimal parallel estrogenic regulation of EM2 release.

mGluR1 Independence of EM2 Suppression

Certain mER signal transduction cascades require activation of mGluRs, which are functionally coupled to mERs within caveolae [25, 26]. For example, activation of sexual receptivity and lordosis behavior in female rats via mERα is mGluR1 dependent [80]. Additionally, in cultured hippocampal neurons, activation of mERα recruits mGluR1, leading to phosphorylation of CREB by MAP-kinase within 5 min [27]. These functional interactions between mERα and mGluR1 led us to hypothesize that suppression of EM2 release via mERα and GPR30 might be mGluR1 dependent as well. However, unlike ERα/GPR30 blockade, mGluR1 blockade failed to enhance spinal EM2 release. Notably, this does not preclude the possible relevance of other mGluRs to mER-mediated antinociceptive mechanisms. For example, estrogenic suppression of pronociceptive calcium currents in DRG neurons via mERs requires activation of mGluR2 and mGluR3 [81].

Estrogenic Suppression of EM2 Release Is Estrous Cycle Dependent

The magnitude of enhanced EM2 release following spinal ERα/GPR30 blockade (reflecting the magnitude of ongoing mER-mediated suppression of EM2 release) was greater during proestrus than diestrus and not observable during estrus (or in males). This dependence on stage of estrous cycle suggests a correlation with the ebb and flow of circulating levels of E2, which are highest in proestrous females (146.8–367 pm), intermediate in diestrous females (up to 135.8 pm), and lowest in estrous females (as low as 18.40 pm) and males (<18.35 pm) [10, 12–15]. This, along with the negative correlation between the magnitude of basal EM2 release and circulating E2 levels (i.e. basal EM2 release is highest during estrus, when circulating E2 is lowest), suggests that spinal estrogenic activity acts as a physiological clamp to suppress EM2 release. (Differences in basal spinal EM2 release between proestrus and diestrus, expected to be smaller than differences between proestrus/diestrus and estrus, were likely obscured by between-subject variations in EM2 release.) Nonestrogenic contributions to the regulation of spinal EM2 release, however, cannot be ruled out since the secretion of ovarian factors in addition to estrogens (e.g. progesterone, inhibin) also varies across the estrous cycle.

The relationship between sex/estrous stage and nociception is exceedingly complex, varying with species/strain, nature of the painful stimulus, location of pain, method of measurement, and the interactions among these variables [16, 82]. In rats, sensitivity to colorectal distension is higher in proestrus than diestrus [83], but sensitivity to ureteral pain is higher in diestrus than proestrus [84]. Additionally, the relationship between estrous cycle stage and analgesic effectiveness of morphine varies with its route of administration. For example, in rats, subcutaneous morphine produces greater analgesia during proestrus/diestrus than estrus when measured via tail flick [85] or hotplate [86], but morphine administered intracerebroventricularly elicits comparable analgesia across all estrous cycle stages when measured via tail flick or shock-jump [87]. The variable dependence on stage of estrous cycle among different antinociceptive systems could indicate that analgesic mechanisms differ in their sensitivity to estrogens and/or that spinal estrogenic activity is not only compartmentalized but also asynchronously regulated.

Estrogenic Suppression of EM2 Release Is Sexually Dimorphic

A female-specific mechanism for suppressing spinal EM2 release is consistent with a range of findings demonstrating the relative inability of females to harness MOR-coupled antinociception. For example, many MOR-preferring agonists produce more powerful analgesia and greater CNS activation in males than females [34–43], and basal/K+-evoked spinal EM2 release is greater in males than females in vitro [44]. Furthermore, the inference that peripheral levels of estrogens influence the magnitude of ongoing suppression of spinal EM2 release is consonant with these findings and with the absence of any effect of spinal ERα/GPR30 blockade on EM2 release in males (where circulating levels of estrogens are substantially lower than in females) [10, 11].

The Female-Specific Plasticity of Estrogenic Regulation Coordinates Spinal EM2 Utilization with Physiological Demand

Fluctuating estrogenic suppression of spinal EM2 release directly parallels the estrogen-dependent formation of MOR/KOR heterodimers, which is also greater in proestrus than diestrus [22, 88]. Monomeric spinal KOR subserves pronociceptive functions [for review, see 89] without producing detectable spinal antinociception [88, 90–93]. In contrast, activation of KOR (concomitant with MOR) within the MOR/KOR heterodimer unveils antinociceptive attributes of KOR. Therefore, during diestrus, when expression of MOR/KOR ebbs, the pronociceptive functions of spinal KOR are likely to prevail, while during proestrus, the pronociceptive functions of KOR are diminished by the increased formation of MOR/KOR. Consequently, the activation of MOR (by endomorphins) required to counterbalance the activation of KOR (by dynorphins) should be relatively high in diestrus versus proestrus, providing a physiological rationale for our observation that estrogenic suppression of spinal EM2 release is highest during proestrus and greatly reduced during diestrus. The inverse modulation by estrogens of spinal EM2 release and MOR/KOR formation [22] provides a mechanism for coordinating spinal EM2 utilization with physiological demand.

Perturbation of Cycle-Dependent Opioid Antinociceptive Mechanisms May Predispose Women to Chronic Pain Syndromes

Although the disinhibition of spinal EM2 release produced by ERα/GPR30 blockade was sexually dimorphic, basal EM2 release did not differ between the sexes. This suggests that tonic spinal endomorphic tone is unlikely to account for sex differences in the severity and frequency of pain syndromes. However, the variable estrogenic suppression of spinal EM2 release could account, in part, for changes in pain sensitivity observed across the estrous cycle in rats [4] and the menstrual cycle in women [3]. Moreover, malfunctions in the coordination of spinal MOR/KOR heterodimer formation with estrogenic suppression of EM2 release could be biological factors that predispose women to develop chronic pain syndromes.

Spinal EM2 Suppression Requires both Peripheral and Central Estrogens

Both ovariectomy and inhibition of spinal aromatase, individually, eliminated mER suppression of EM2 release in females, suggesting that the estrogenic regulation of spinal EM2 release requires cooperative action of both peripheral and central estrogens. The involvement of an ovarian factor is also supported by the apparent relationship between estrous cycle stage and the magnitude of suppression of EM2 release. Previous studies have demonstrated roles for either peripheral or central estrogens in regulating pain physiology. For example, in rats, ovariectomy decreases sensitivity to formalin-induced pain [94]; inhibition of spinal aromatase decreases pain sensitivity in both male and female quails [18]; and in proestrous female rats, inhibition of spinal aromatase reduces MOR/KOR dimerization and eliminates the KOR dependency of morphine antinociception [22]. Interestingly, the present study identifies a mechanism that relies on both peripheral and central estrogens, implicating a possible interaction between these two pools of estrogens.

The functional relationship between central and peripheral estrogens remains largely unexplored and has been the subject of much speculation [95]. Peripheral estrogens, which reach the CNS by penetrating the blood-brain barrier and diffusing from cerebrospinal fluid into extracellular fluid [96], could act directly on spinal mERs to suppress EM2 release. In parallel, central estrogens are synthesized by spinal aromatase near synaptic structures, and could also activate nearby mERs [18, 19, 97–99]. It is possible that a critical threshold of estrogens is essential for spinal mER suppression of EM2 release, which could be achieved by the summation of peripheral and central estrogens. However, such a threshold would produce ‘all-or-none’ EM2 suppression, and would not be consistent with the graded magnitude of mER inhibition of EM2 release that is manifest over the estrous cycle. Accordingly, it is more likely that peripheral and central estrogens act synergistically to modulate spinal EM2 utilization. The mechanism(s) underlying putative synergistic interactions between centrally and peripherally synthesized estrogens are not known. Given indications that diffusion of centrally synthesized estrogens is highly spatially restricted [95, 100–103], it is possible that CNS- and ovarian-derived estrogens activate different populations of spinal ERs that are functionally convergent. Current findings support the imperative to investigate points of convergence (in the CNS) of the actions of centrally and peripherally derived estrogens.

Synergistic interactions in the CNS between central and peripheral estrogens likely involve their coordinated synthesis. The synthesis of peripheral estrogens requires the activity of ovarian aromatase, which is synchronized with the estrous cycle, being (slowly) regulated by the pituitary gonadotropins luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone [17]. CNS aromatase activity, in contrast, is regulated both slowly (hours to days) by sex steroids [104–106] and rapidly (within minutes) by a variety of local factors including intracellular calcium concentration, glutamate receptor activity, and phosphorylation by protein kinases A and C [107–110]. Points of intersection among the pathways regulating peripheral versus central aromatase activity remain to be elucidated.

The mechanisms underlying the cooperative actions of central and peripheral estrogens to suppress spinal EM2 release could represent novel pharmacological targets for relief of pain in women, enabling improved utilization of endogenous EM2. The pliability of EM2 utilization, strikingly absent in male rats, may contribute to women’s elevated risk of developing chronic pain conditions while also providing an opportunity for therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, R01DA027663, to A.R.G.

References

- 1.Fillingim RB, Gear RW. Sex differences in opioid analgesia: clinical and experimental findings. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL., 3rd Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain. 2009;10:447–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teepker M, Peters M, Vedder H, Schepelmann K, Lautenbacher S. Menstrual variation in experimental pain: correlation with gonadal hormones. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;61:131–140. doi: 10.1159/000279303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibironke GF, Aji KE. Pain threshold variations in female rats as a function of the estrus cycle. Niger J Physiol Sci. 2011;26:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craft RM, Mogil JS, Aloisi AM. Sex differences in pain and analgesia: the role of gonadal hormones. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:397–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craft RM. Sex differences in opioid analgesia: ‘from mouse to man’. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:175–186. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200305000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mogil JS, Chesler EJ, Wilson SG, Juraska JM, Sternberg WF. Sex differences in thermal nociception and morphine antinociception in rodents depend on genotype. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:375–389. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aloisi AM, Ceccarelli I. Role of gonadal hormones in formalin-induced pain responses of male rats: modulation by estradiol and naloxone administration. Neuroscience. 2000;95:559–566. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00445-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aloisi AM, Ceccarelli I, Fiorenzani P. Gonadectomy affects hormonal and behavioral responses to repetitive nociceptive stimulation in male rats. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;1007:232–237. doi: 10.1196/annals.1286.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornil CA, Ball GF, Balthazart J. Functional significance of the rapid regulation of brain estrogen action: where do the estrogens come from? Brain Res. 2006;1126:2–26. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haim S, Shakhar G, Rossene E, Taylor AN, Ben-Eliyahu S. Serum levels of sex hormones and corticosterone throughout 4- and 5-day estrous cycles in Fischer 344 rats and their simulation in ovariectomized females. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26:1013–1022. doi: 10.1007/BF03348201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahdieh HB, Siegel HI, Wade GN. The role of the uterus in regulation of heat duration in cycling rats. Horm Behav. 1985;19:292–303. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(85)90028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeo Y. Influence of continuous illumination on estrous cycle of rats: time course of changes in levels of gonadotropins and ovarian steroids until occurrence of persistent estrus. Neuroendocrinology. 1984;39:97–104. doi: 10.1159/000123964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butcher RL, Collins WE, Fugo NW. Plasma concentration of LH, FSH, prolactin, progesterone and estradiol-17beta throughout the 4-day estrous cycle of the rat. Endocrinology. 1974;94:1704–1708. doi: 10.1210/endo-94-6-1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith MS, Freeman ME, Neill JD. The control of progesterone secretion during the estrous cycle and early pseudopregnancy in the rat: prolactin, gonadotropin and steroid levels associated with rescue of the corpus luteum of pseudopregnancy. Endocrinology. 1975;96:219–226. doi: 10.1210/endo-96-1-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gintzler AR, Liu NJ. Importance of sex to pain and its amelioration; relevance of spinal estrogens and its membrane receptors. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2012;33:412–424. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. ed 12. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evrard HC, Balthazart J. Rapid regulation of pain by estrogens synthesized in spinal dorsal horn neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7225–7229. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1638-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evrard HC. Estrogen synthesis in the spinal dorsal horn: a new central mechanism for the hormonal regulation of pain. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R291–R299. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00930.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gintzler AR, Liu NJ. Importance of sex to pain and its amelioration; relevance of spinal estrogens and its membrane receptors. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2012;33:412–424. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaban VV, Mayer EA, Ennes HS, Micevych PE. Estradiol inhibits ATP-induced intracellular calcium concentration increase in dorsal root ganglia neurons. Neuroscience. 2003;118:941–948. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00915-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu NJ, Chakrabarti S, Schnell S, Wessendorf M, Gintzler AR. Spinal synthesis of estrogen and concomitant signaling by membrane estrogen receptors regulate spinal kappa- and mu-opioid receptor heterodimerization and female-specific spinal morphine antinociception. J Neurosci. 2011;31:11836–11845. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1901-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonini JA, Anderson SM, Steiner DF. Molecular cloning and tissue expression of a novel orphan G protein-coupled receptor from rat lung. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;234:190–193. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carmeci C, Thompson DA, Ring HZ, Francke U, Weigel RJ. Identification of a gene (GPR30) with homology to the G-protein-coupled receptor superfamily associated with estrogen receptor expression in breast cancer. Genomics. 1997;45:607–617. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boulware MI, Kordasiewicz H, Mermelstein PG. Caveolin proteins are essential for distinct effects of membrane estrogen receptors in neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9941–9950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1647-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mermelstein PG. Membrane-localised oestrogen receptor alpha and beta influence neuronal activity through activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21:257–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01838.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boulware MI, Weick JP, Becklund BR, Kuo SP, Groth RD, Mermelstein PG. Estradiol activates group I and II metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling, leading to opposing influences on camp response element-binding protein. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5066–5078. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1427-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levin ER. Rapid signaling by steroid receptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1425–R1430. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90605.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fichna J, Janecka A, Costentin J, Do Rego JC. The endomorphin system and its evolving neurophysiological role. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:88–123. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zadina JE, Hackler L, Ge LJ, Kastin AJ. A potent and selective endogenous agonist for the muopiate receptor. Nature. 1997;386:499–502. doi: 10.1038/386499a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakurada S, Hayashi T, Yuhki M, Fujimura T, Murayama K, Yonezawa A, Sakurada C, Takeshita M, Zadina JE, Kastin AJ, Sakurada T. Differential antagonism of endomorphin-1 and endomorphin-2 spinal antinociception by naloxonazine and 3-methoxynaltrexone. Brain Res. 2000;881:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02770-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soignier RD, Vaccarino AL, Brennan AM, Kastin AJ, Zadina JE. Analgesic effects of endomorphin-1 and endomorphin-2 in the formalin test in mice. Life Sci. 2000;67:907–912. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00689-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanderson Nydahl K, Skinner K, Julius D, Basbaum AI. Co-localization of endomorphin-2 and substance p in primary afferent nociceptors and effects of injury: a light and electron microscopic study in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1789–1799. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrett AC, Smith ES, Picker MJ. Sex-related differences in mechanical nociception and antinociception produced by mu- and kappaopioid receptor agonists in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;452:163–173. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cicero TJ, Nock B, Meyer ER. Sex-related differences in morphine’s antinociceptive activity: relationship to serum and brain morphine concentrations. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:939–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cicero TJ, Nock B, Meyer ER. Gender-related differences in the antinociceptive properties of morphine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;279:767–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyer JS, Morgan MM, Craft RM. Microin-jection of morphine into the rostral ventro-medial medulla produces greater antinociception in male compared to female rats. Brain Res. 1998;796:315–318. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00353-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krzanowska EK, Bodnar RJ. Morphine antinociception elicited from the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray is sensitive to sex and gonadectomy differences in rats. Brain Res. 1999;821:224–230. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01364-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cook CD, Barrett AC, Roach EL, Bowman JR, Picker MJ. Sex-related differences in the anti-nociceptive effects of opioids: importance of rat genotype, nociceptive stimulus intensity, and efficacy at the mu opioid receptor. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;150:430–442. doi: 10.1007/s002130000453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peckham EM, Barkley LM, Divin MF, Cicero TJ, Traynor JR. Comparison of the antinociceptive effect of acute morphine in female and male Sprague-Dawley rats using the long-lasting mu-antagonist methocinnamox. Brain Res. 2005;1058:137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peckham EM, Traynor JR. Comparison of the antinociceptive response to morphine and morphine-like compounds in male and female Sprague-Dawley rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:1195–1201. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.094276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ji Y, Murphy AZ, Traub RJ. Sex differences in morphine-induced analgesia of visceral pain are supraspinally and peripherally mediated. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R307–R314. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00824.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X, Traub RJ, Murphy AZ. Persistent pain model reveals sex difference in morphine potency. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R300–R306. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00022.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta DS, von Gizycki H, Gintzler AR. Sex-/ovarian steroid-dependent release of endomorphin 2 from spinal cord. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:635–641. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.118505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu NJ, Gintzler AR. Spinal endomorphin 2 antinociception and the mechanisms that produce it are both sex- and stage of estrus cycle-dependent in rats. J Pain. 2013;14:1522–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marks HE, Hobbs SH. Changes in stimulus reactivity following gonadectomy in male and female rats of different ages. Physiol Behav. 1972;8:1113–1119. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(72)90206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu NJ, Schnell SA, Schulz S, Wessendorf MW, Gintzler AR. Regulation of spinal dynorphin 1–17 release by endogenous pituitary adenylyl cyclase-activating polypeptide in the male rat: relevance of excitation via disinhibition. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:328–335. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.173039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albanito L, Madeo A, Lappano R, Vivacqua A, Rago V, Carpino A, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER, Musti AM, Ando S, Maggiolini M. G protein-coupled receptor 30 (GPR30) mediates gene expression changes and growth response to 17beta-estradiol and selective GPR30 ligand G-1 in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1859–1866. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Razandi M, Pedram A, Greene GL, Levin ER. Cell membrane and nuclear estrogen receptors (ERs) originate from a single transcript: studies of ERalpha and ERbeta expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Endocrinol (Baltimore) 1999;13:307–319. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.2.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vivacqua A, Bonofiglio D, Recchia AG, Musti AM, Picard D, Ando S, Maggiolini M. The G protein-coupled receptor GPR30 mediates the proliferative effects induced by 17beta-estradiol and hydroxytamoxifen in endometrial cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:631–646. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Y, Xiao X, Zhang XM, Zhao ZQ, Zhang YQ. Estrogen facilitates spinal cord synaptic transmission via membrane-bound estrogen receptors: implications for pain hypersensitivity. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:33268–33281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.368142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fukunaga I, Yeo CH, Batchelor AM. Potent and specific action of the mGlu1 antagonists YM-298198 and JNJ16259685 on synaptic transmission in rat cerebellar slices. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:870–876. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kohara A, Toya T, Tamura S, Watabiki T, Nagakura Y, Shitaka Y, Hayashibe S, Kawabata S, Okada M. Radioligand binding properties and pharmacological characterization of 6-amino-N-cyclohexyl-N,3-dimethylthiazolo[3, 2-a]benzimidazole-2-carboxamide (YM-298198), a high-affinity, selective, and noncompetitive antagonist of metabotropic glutamate receptor type 1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:163–169. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.087171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoon MH, Choi J, Bae HB, Kim SJ, Chung ST, Jeong SW, Chung SS, Yoo KY, Jeong CY. Antinociceptive effects and synergistic interaction with morphine of intrathecal metabotropic glutamate receptor 2/3 antagonist in the formalin test of rats. Neurosci Lett. 2006;394:222–226. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kohara A, Nagakura Y, Kiso T, Toya T, Watabiki T, Tamura S, Shitaka Y, Itahana H, Okada M. Antinociceptive profile of a selective metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 antagonist YM-230888 in chronic pain rodent models. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;571:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bondar G, Kuo J, Hamid N, Micevych P. Estradiol-induced estrogen receptor-alpha trafficking. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15323–15330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2107-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levin ER. Plasma membrane estrogen receptors. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:477–482. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rai D, Frolova A, Frasor J, Carpenter AE, Katzenellenbogen BS. Distinctive actions of membrane-targeted versus nuclear localized estrogen receptors in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1606–1617. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zheng J, Ramirez VD. Demonstration of membrane estrogen binding proteins in rat brain by ligand blotting using a 17beta-estra-diol-[125i]bovine serum albumin conjugate. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;62:327–336. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(97)00037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lawson KP, Nag S, Thompson AD, Mokha SS. Sex-specificity and estrogen-dependence of kappa opioid receptor-mediated antinociception and antihyperalgesia. Pain. 2010;151:806–815. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sarajari S, Oblinger MM. Estrogen effects on pain sensitivity and neuropeptide expression in rat sensory neurons. Exp Neurol. 2010;224:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guertin MJ, Zhang X, Coonrod SA, Hager GL. Transient estrogen receptor binding and p300 redistribution support a squelching mechanism for estradiol-repressed genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28:1522–1533. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lanaud P, Maggio R, Gale K, Grayson DR. Temporal and spatial patterns of expression of c-fos, zif/268, c-jun and jun-B mRNAs in rat brain following seizures evoked focally from the deep prepiriform cortex. Exp Neurol. 1993;119:20–31. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Madeo A, Maggiolini M. Nuclear alternate estrogen receptor GPR30 mediates 17beta-estradiol-induced gene expression and migration in breast cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6036–6046. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vasudevan N, Pfaff DW. Membrane-initiated actions of estrogens in neuroendocrinology: emerging principles. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:1–19. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Levin ER. Integration of the extranuclear and nuclear actions of estrogen. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1951–1959. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB, Sklar LA. GPR30: a G protein-coupled receptor for estrogen. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;265–266:138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Revankar CM, Cimino DF, Sklar LA, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER. A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science. 2005;307:1625–1630. doi: 10.1126/science.1106943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dun SL, Brailoiu GC, Gao X, Brailoiu E, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER, Oprea TI, Dun NJ. Expression of estrogen receptor GPR30 in the rat spinal cord and in autonomic and sensory ganglia. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:1610–1619. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Noel SD, Keen KL, Baumann DI, Filardo EJ, Terasawa E. Involvement of G protein-coupled receptor 30 (GPR30) in rapid action of estrogen in primate LHRH neurons. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:349–359. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kuhn J, Dina OA, Goswami C, Suckow V, Levine JD, Hucho T. GPR30 estrogen receptor agonists induce mechanical hyperalgesia in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:1700–1709. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pedram A, Razandi M, Levin ER. Nature of functional estrogen receptors at the plasma membrane. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1996–2009. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Otto C, Rohde-Schulz B, Schwarz G, Fuchs I, Klewer M, Brittain D, Langer G, Bader B, Prelle K, Nubbemeyer R, Fritzemeier KH. G protein-coupled receptor 30 localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum and is not activated by estradiol. Endocrinology. 2008;149:4846–4856. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Madak-Erdogan Z, Kieser KJ, Kim SH, Komm B, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Nuclear and extranuclear pathway inputs in the regulation of global gene expression by estrogen receptors. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:2116–2127. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Akama KT, Thompson LI, Milner TA, McEwen BS. Post-synaptic density-95 (PSD-95) binding capacity of G-protein-coupled receptor 30 (GPR30), an estrogen receptor that can be identified in hippocampal dendritic spines. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:6438–6450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.412478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xu H, Qin S, Carrasco GA, Dai Y, Filardo EJ, Prossnitz ER, Battaglia G, Doncarlos LL, Muma NA. Extra-nuclear estrogen receptor GPR30 regulates serotonin function in rat hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1599–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rossi DV, Dai Y, Thomas P, Carrasco GA, DonCarlos LL, Muma NA, Li Q. Estradiol-induced desensitization of 5-HT1A receptor signaling in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus is independent of estrogen receptor-beta. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:1023–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hammond R, Gibbs RB. GPR30 is positioned to mediate estrogen effects on basal forebrain cholinergic neurons and cognitive performance. Brain Res. 2011;1379:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hammond R, Nelson D, Gibbs RB. GPR30 co-localizes with cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain and enhances potassium-stimulated acetylcholine release in the hippocampus. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dewing P, Boulware MI, Sinchak K, Christensen A, Mermelstein PG, Micevych P. Membrane estrogen receptor-alpha interactions with metabotropic glutamate receptor 1a modulate female sexual receptivity in rats. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9294–9300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0592-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chaban V, Li J, McDonald JS, Rapkin A, Micevych P. Estradiol attenuates the adenosine triphosphate-induced increase of intracellular calcium through group ii metabotropic glutamate receptors in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89:1707–1710. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu NJ, Schnell S, Wessendorf MW, Gintzler AR. Sex, pain and opioids: Inter-dependent influences of sex and pain modality on dynorphin-mediated antinociception in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;344:522–530. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.199851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ji Y, Tang B, Traub RJ. The visceromotor response to colorectal distention fluctuates with the estrous cycle in rats. Neuroscience. 2008;154:1562–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.04.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Giamberardino MA, Affaitati G, Valente R, Iezzi S, Vecchiet L. Changes in visceral pain reactivity as a function of estrous cycle in female rats with artificial ureteral calculosis. Brain Res. 1997;774:234–238. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)81711-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Banerjee P, Chatterjee TK, Ghosh JJ. Ovarian steroids and modulation of morphine-induced analgesia and catalepsy in female rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1983;96:291–294. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(83)90319-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stoffel EC, Ulibarri CM, Craft RM. Gonadal steroid hormone modulation of nociception, morphine antinociception and reproductive indices in male and female rats. Pain. 2003;103:285–302. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00457-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kepler KL, Kest B, Kiefel JM, Cooper ML, Bodnar RJ. Roles of gender, gonadectomy and estrous phase in the analgesic effects of intra-cerebroventricular morphine in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1989;34:119–127. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chakrabarti S, Liu NJ, Gintzler AR. Formation of mu-/kappa-opioid receptor heterodimer is sex-dependent and mediates female-specific opioid analgesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20115–20119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009923107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lai J, Ossipov MH, Vanderah TW, Malan TP, Jr, Porreca F. Neuropathic pain: the paradox of dynorphin. Mol Interv. 2001;1:160–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stevens CW, Yaksh TL. Dynorphin A and related peptides administered intrathecally in the rat: a search for putative kappa opiate receptor activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1986;238:833–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Przewlocka B, Dziedzicka M, Lason W, Przewlocki R. Differential effects of opioid receptor agonists on nociception and camp level in the spinal cord of monoarthritic rats. Life Sci. 1992;50:45–54. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90196-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Piercey MF, Einspahr FJ. Spinal analgesic actions of kappa receptor agonists, u-50488h and spiradoline (u-62066) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251:267–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schmauss C. Spinal kappa-opioid receptor-mediated antinociception is stimulus-specific. Eur J Pharmacol. 1987;137:197–205. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gaumond I, Arsenault P, Marchand S. The role of sex hormones on formalin-induced nociceptive responses. Brain Res. 2002;958:139–145. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03661-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schlinger BA, Remage-Healey L, Rensel M. Establishing regional specificity of neuroestrogen action. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2014;205:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Guyton A, Hall JE. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. ed 12. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hojo Y, Hattori TA, Enami T, Furukawa A, Suzuki K, Ishii HT, Mukai H, Morrison JH, Janssen WG, Kominami S, Harada N, Kimoto T, Kawato S. Adult male rat hippocampus synthesizes estradiol from pregnenolone by cytochromes P45017alpha and P450 aromatase localized in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:865–870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2630225100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Naftolin F, Horvath TL, Jakab RL, Leranth C, Harada N, Balthazart J. Aromatase immunoreactivity in axon terminals of the vertebrate brain. An immunocytochemical study on quail, rat, monkey and human tissues. Neuroendocrinology. 1996;63:149–155. doi: 10.1159/000126951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Peterson RS, Yarram L, Schlinger BA, Saldanha CJ. Aromatase is pre-synaptic and sexually dimorphic in the adult zebra finch brain. Proc Biol Sci. 2005;272:2089–2096. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Remage-Healey L, Maidment NT, Schlinger BA. Forebrain steroid levels fluctuate rapidly during social interactions. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1327–1334. doi: 10.1038/nn.2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Charlier TD, Newman AE, Heimovics SA, Po KW, Saldanha CJ, Soma KK. Rapid effects of aggressive interactions on aromatase activity and oestradiol in discrete brain regions of wild male white-crowned sparrows. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23:742–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chao A, Schlinger BA, Remage-Healey L. Combined liquid and solid-phase extraction improves quantification of brain estrogen content. Front Neuroanat. 2011;5:57. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2011.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fokidis HB, Prior NH, Soma KK. Fasting increases aggression and differentially modulates local and systemic steroid levels in male zebra finches. Endocrinology. 2013;154:4328–4339. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Abdelgadir SE, Resko JA, Ojeda SR, Lephart ED, McPhaul MJ, Roselli CE. Androgens regulate aromatase cytochrome p450 messenger ribonucleic acid in rat brain. Endocrinology. 1994;135:395–401. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.1.8013375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Roselli CE, Resko JA. Cytochrome P450 aromatase (CYP19) in the non-human primate brain: distribution, regulation, and functional significance. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;79:247–253. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schumacher M, Balthazart J. Testosterone-induced brain aromatase is sexually dimorphic. Brain Res. 1986;370:285–293. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90483-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Balthazart J, Baillien M, Ball GF. Phosphorylation processes mediate rapid changes of brain aromatase activity. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;79:261–277. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Balthazart J, Baillien M, Ball GF. Rapid and reversible inhibition of brain aromatase activity. J Neuroendocrinol. 2001;13:63–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2001.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Balthazart J, Baillien M, Ball GF. Rapid control of brain aromatase activity by glutamatergic inputs. Endocrinology. 2006;147:359–366. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Balthazart J, Baillien M, Charlier TD, Cornil CA, Ball GF. Multiple mechanisms control brain aromatase activity at the genomic and non-genomic level. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;86:367–379. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00346-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]