Abstract

B lymphopoiesis requires that immunoglobulin genes be accessible to the RAG1-RAG2 recombinase. However, the RAG proteins bind widely to open chromatin suggesting that additional mechanisms must restrict RAG-mediated DNA cleavage. Here, we demonstrate developmental downregulation of interleukin 7 (IL-7) receptor signaling in small pre-B cells induced expression of the bromodomain family member BRWD1, which was recruited to a specific epigenetic landscape at Igk dictated by pre-BCR-dependent Erk activation. BRWD1 enhanced RAG recruitment, increased gene accessibility and positioned nucleosomes 5′ to each Jκ recombination signal sequence. BRWD1 thus targets recombination to Igk and places recombination within the context of signaling cascades that control B cell development. Our findings provide a paradigm in which, at any particular antigen receptor locus, specialized mechanisms enforce lineage and stage specific recombination.

The defining event of B lymphopoiesis is immunoglobulin gene (Ig) recombination1. Rearrangement begins with the Igh locus and recombination of diversity (D) to joining (J) gene segments in pre-pro B cells followed by variable (V) gene segments to DJ in late pro-B cells2. Following in-frame recombination, expressed Igμ chain assembles with the surrogate light chain (λ5 and VpreB) and Igα–Igβ to form a pre-B cell receptor (pre-BCR). Expression of the pre-BCR is associated with IL-7–dependent clonal expansion2. However, pre-B cells must exit cell cycle before initiating Igk recombination. Failure to do so risks genomic instability and leukemic transformation3.

Ig recombination is dependent upon both expression of recombinase proteins encoded by the recombination-activating genes Rag1 and Rag2 and accessibility of targeted genes to the recombination machinery4. Gene accessibility was first proposed to be required for recombination in 19855 and subsequent studies demonstrated close correlations between Ig recombination, transcription6 and marks of open chromatin7. Elegant in vitro studies have demonstrated that chromatin structure both restricts and enables Ig gene recombination1. Furthermore, determiners of Ig gene transcription, including cis-acting enhancers and transcription factors (TFs), also regulate Ig gene recombination1,2,7,8.

For the Igk locus, Igk germline transcription (κGT) and the epigenetic landscape are determined by antagonistic signaling cascades downstream of the IL-7R and the pre-BCR2. The IL-7R activates STAT5, which binds to the Igk intronic enhancer (Eκi) and recruits the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) which decorates regional chromatin, including Jκ and Cκ, with trimethyl groups at lysine 27 of histone H3 (H3K27me3)9. Expression of the pre-BCR is associated with subsequent escape from IL-7R dependent STAT5 activation2 leading to cell cycle exit10 and derepression of Igk9. Pre-BCR–induced E2A can then bind the Eκi and 3′ kappa enhancer (3′Eκ), recruit histone acetyl-transferases and augment Igk transcription9,11.

Some studies indicate that transcription itself is required for recombination6,12 while others have noted a discordance between transcription and recombination13,14. It might be that the epigenetic state associated with transcriptional activation is a more universal requirement of antigen receptor gene recombination as H3K4me3, a mark of open chromatin, directly recruits RAG215,16,17. This observation directly links the epigenetic landscape to recombination.

A role for H3K4me3 in recombination suggests specific restrictions on how accessibility would be regulated at Ig genes targeted for recombination. Nucleosomes would have to be present within targeted loci to recruit RAG2. However, nucleosomes at recombination signal sequences (RSSs, which include nonamer and heptamer motifs) inhibit RAG-mediated cleavage18,19,20, while in vitro, nucleosomes preferentially position over RSS sites1,18. These data suggest that nucleosomes, bearing H3K4me3, would need to be positioned adjacent to RSSs by mechanisms not solely reliant upon underlying DNA sequence21,22.

Furthermore, it is not clear if the known mechanisms of gene accessibility and recombination are sufficient to restrict recombination to specific Ig loci at particular developmental transitions. In small pre-B cells, both RAG1 and RAG2 are recruited to thousands of sites bearing H3K4me31,23. Furthermore cryptic RSS (cRSSs), which can be cleaved by RAG24,25, are predicted to occur at millions of sites across the genome26. Yet, in small pre-B cells, recombination is normally restricted to the Igk loci. These observations suggest that there must be additional, unknown factors that target and restrict recombination to Igk in small pre-B cells.

Herein, we demonstrate that the dual bromodomain family member BRWD1 targets Igk for recombination. BRWD1 is rapidly induced following escape from IL-7R signaling and is then recruited to Jκ by a specific epigenetic code imparted by pre-BCR dependent signals. Binding of BRWD1 at Jκ both opens regional chromatin and positions nucleosomes relative to DNA GAGA motifs to enable RAG recruitment and Igk recombination.

RESULTS

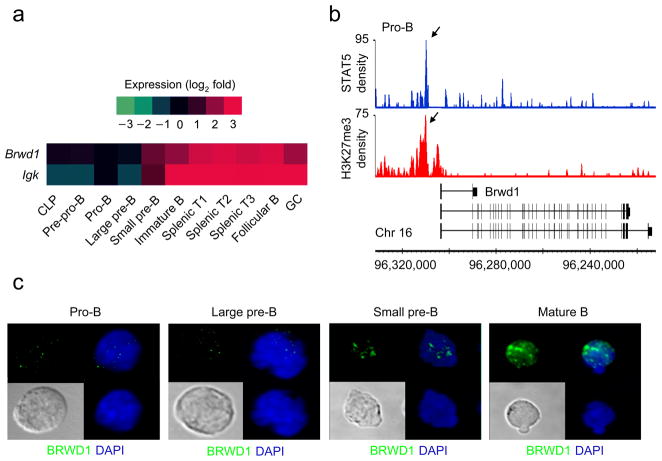

STAT5 directly represses Brwd1

In pro-B cells, STAT5-mediated repression is usually associated with stable silencing of target genes through subsequent stages of B lymphopoiesis9. Of the 47 genes repressed by STAT5 in pro-B cells9, only two genes, κGT and Brwd1 (Fig. 1a) were immediately and strongly induced upon transition to the small pre-B cell stage. BRWD1 was a direct target of STAT5 as it bound the Brwd1 promoter region and STAT5 binding was associated with co-incident and flanking H3K27me3 repressive marks (Fig. 1b). Brwd1 demonstrates a similar expression pattern to Igk throughout B cell development, and like Igk, its expression is primarily restricted to the B cell lineage. BRWD1 is a histone lysine acetylation reader27 and a member of the dual bromodomain and WD40 repeat protein families which associates with the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex28. These features predict nuclear localization. Indeed, confocal microscopy of flow cytometry-sorted wild-type primary B cell progenitors indicated that BRWD1 expression was induced after the pro-B cell stage and that most BRWD1 resided in the nucleus (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

STAT5-regulated Brwd1 expression during B lymphopoiesis. (a) Heat map of Igk and Brwd1 expression presented as change in expression (log2) as a function of B cell development and maturation relative to the pro-B cell stage (ImmGen Consortium). (b) Cultured Rag2−/− pro-B cells were subjected to ChIP-Seq with STAT5 and H3K27me3 specific antibodies as described. Reads were aligned to the Brwd1 gene and are presented as smoothed tag densities. Data are representative of two experiments. (c) Localization of BRWD1 in different flow sorted B cell progenitors from wild-type bone marrow by confocal microscopy. Data are representative of 9 images from two independent experiments.

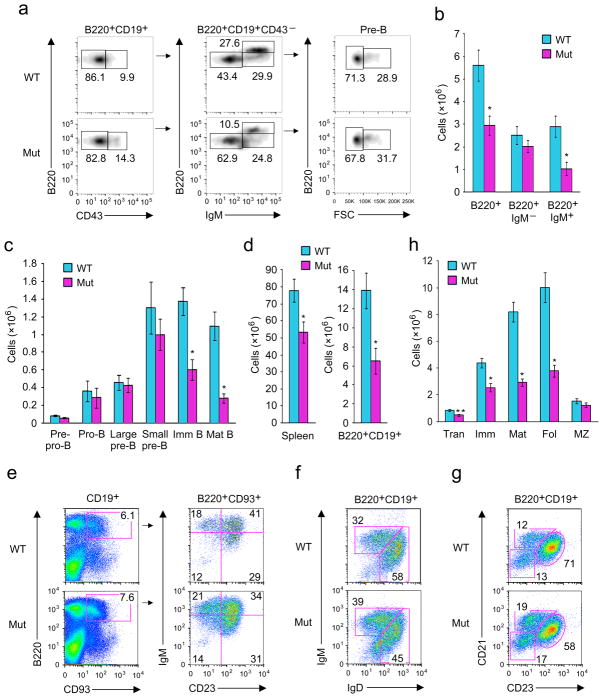

BRWD1 is required for B lymphopoiesis

To examine if BRWD1 was important in B lymphopoiesis, we obtained Brwd1mut (Brwd1mut/mut) mice29 which contain an ethylnitrosourea (ENU)-induced single point mutation at the exon 10-intron 10 junction of Brwd1. These mice, originally derived on a C57BL/J6 background, were then extensively back-crossed to C3HeB/FeJ to isolate the mutation to a 1.8 Mb region on chromosome 16 (ref. 29). cDNAs from wild-type and Brwd1mut bone marrow (BM), and splenic B220+ B cells10, were sequenced to confirm that the identified mutation induced exon skipping and a frame-shift that generated premature stop codons (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1a–c). Immunoblotting of Brwd1mut splenic B cells with an antibody specific for the N-terminal domain of BRWD1 did not detect either the wild-type BRWD1 bands or any smaller molecular weight species (Supplementary Fig. 1d).

Next, BM and spleens were harvested from Brwd1mut or wild-type littermate-control mice and B lymphopoiesis was analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 2). There were diminished frequencies of later-stage B cell progenitors in Brwd1mut mice (Fig. 2a). Total numbers of B220+ BM cells were decreased in Brwd1mut mice, as compared to wild-type, and mainly due to a reduction in the IgM+ B cell population (Fig. 2b). The defect began in small pre-B (Lin−B220+CD43−IgM−FSClo) cells and progressively worsened in later BM developmental stages (Fig. 2c). No significant B cell developmental defects were detected in heterozygous Brwd1mut/+ mice (Supplementary Fig. 2a). The developmental defect in Brwd1mut mice persisted into the periphery, with small spleens (data not shown), diminished total splenocytes and decreased numbers of splenic B220+CD19+ B cells (Fig. 2d). Defects in the frequencies and numbers of splenic transitional (B220+CD19+CD93+), immature (B220+CD19+IgMhiIgDlo), mature (B220+CD19+IgMloIgDhi), and follicular (B220+CD19+CD21−CD23+) B cells were detected (Fig. 2e–h). In contrast, the marginal zone (B220+CD19+CD21+CD23−) B cell numbers were relatively preserved (Fig. 2g, h). Subsequent analysis of early common progenitors, other hematopoietic lineages and thymocytes revealed no substantial defects (Supplementary Figs. 2b–l).

Figure 2.

Impaired B lymphopoiesis in Brwd1mut mice. (a) Flow cytometric analysis of different developmental stages of B lymphopoiesis in BM of wild-type (WT) and Brwd1mut (Mut) mice (n=4). Pre-B cells are defined as BM Lin−B220+CD43−IgM− population. (b) BM cellularity and the absolute number of IgM+ and IgM− B cells in WT and Brwd1mut mice (n=3). (c) Absolute numbers of cells/mouse at different stages of B cell development in the BM of WT and Brwd1mut mice (n=4). (d) Numbers of total splenocytes and B cells (CD19+B220+) in spleen of WT and Brwd1mut mice (n=3). (e,f,g) Flow cytometric analysis of transitional B cells (e), immature and mature B cells (f) and follicular and marginal zone B cells (g) in the spleens of WT and Brwd1mut mice (n=3). (h) Absolute numbers of transitional (Tran), immature (Imm), mature (Mat), follicular (Fol) and marginal zone (MZ) B cells in the spleen of WT and Brwd1mut animals (n=3). In all experiments *P<0.001 compared to the respective WT control. **P<0.01 compared to respective controls (unpaired t-test). All bar graphs are presented as average ±s.d.

To assess the competitive fitness of Brwd1mut cells in vivo, we reconstituted sublethally irradiated Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice with an equal mixture of Lin−Sca1+c-Kit+ (LSK) progenitor cells from either wild-type CD45.1 and wild-type CD45.2 mice (Fig. 3a) or wild-type CD45.1 and Brwd1mut CD45.2 mice (Fig. 3b). After 5 weeks, BM was harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 3a, b). LSK cells from wild-type CD45.1 and CD45.2 were equally competent to reconstitute B lymphopoiesis (Fig. 3c). Brwd1mut LSKs could also reconstitute the pro-B and large pre-B cell compartments (Fig. 3d). In contrast, wild-type LSKs contributed 4–5 fold more small pre-B cells than Brwd1mut cells and this bias persisted into the immature and mature B cell compartments (Fig. 3d). Splenic Brwd1mut B cells were also severely diminished (Supplementary Fig. 3a). In the T cell lineage, there was some skewing towards CD4+ cells that may reflect low expression of BRWD1 in double-positive thymocytes (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

BRWD1 is required for normal small pre-B cell development. (a,b) LSK progenitors from WT (CD45.1) and WT (CD45.2) (a) or WT (CD45.1) and Brwd1mut (CD45.2) (b) mice were flow sorted, mixed 1:1, and transplanted into sub-lethally irradiated (550Rads) Rag2−/−Il2rg−/−hosts. B cell development in BM was then analyzed by flow cytometry 5 weeks after transfer. (c,d) Number of cells/mouse for indicated BM B cell progenitors in WT (CD45.1) and WT (CD45.2) (c) or WT (CD45.1) and Brwd1mut (CD45.2) (d) mixed BM chimeras 5 weeks after transfer (each symbol represents one mouse). *P<0.001 compared to the WT small pre-B cells. **P<0.0008 compared to WT immature B cells. **P<0.03 compared to WT mature B cells. (unpaired t-test).

The observed defects in B lymphopoiesis in Brwd1mut mice were not associated with apparent increased frequencies of apoptotic B cell progenitors (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Slightly more Brwd1mut large and small pre-B cells were progressing through the cell cycle (Supplementary Fig. 3d). Cyclin D2 (Ccnd2) expression was slightly diminished and cyclin D3 (Ccnd3)30 was slightly increased in Brwd1mut pre-B cells compared to wild-type littermate controls (Supplementary Fig. 3e). These results suggest that the observed defects in B lymphopoiesis were not due to increased apoptosis or diminished proliferation.

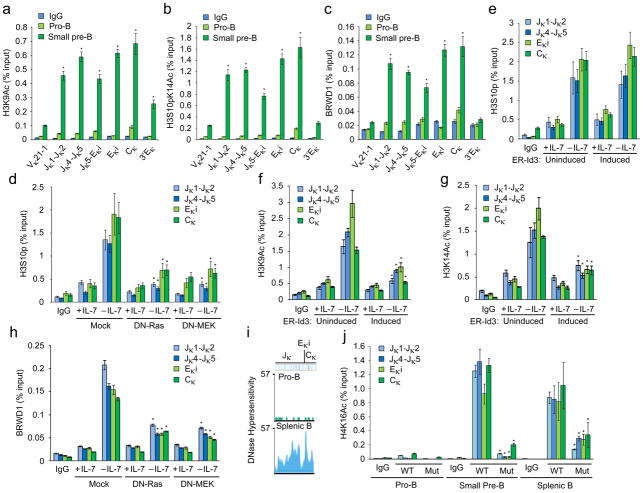

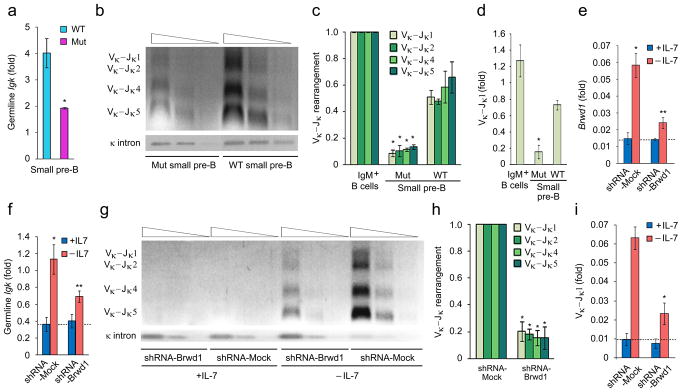

Igk recombination requires BRWD1

As Igk recombination occurs in small pre-B cells, these cells were sorted from wild-type and Brwd1mut mice. κGT expression was decreased approximately two-fold in Brwd1mut mice as compared to wild-type controls (Fig. 4a). In contrast, overall Vκ-Jκ recombination was diminished approximately five-fold compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 4b, c). Quantitative PCR for Vκ-Jκ recombination revealed a similar defect in recombination (Fig. 4d)8. The distribution of Jκ usage in rearranged Igk genes from wild-type and Brwd1mut small pre-B cells was similar (Supplementary Fig. 3f). Likewise Vκ1, Vκ4, Vκ6 and Vκ8 were the most common Vκ segments detected in rearranged Igk genes (Supplementary Fig. 3g). Finally, the frequency of Igλ expressing immature B cells isolated from BM and spleen was also modestly reduced in Brwd1mut mice as compared to wild-type mice (Supplementary Fig. 3h).

Figure 4.

BRWD1 is required for Igk recombination. (a) Quantitative RT-PCR for Igk germline transcription (κGT) in flow sorted small pre-B cells isolated from WT and Brwd1mut mice (n=4). *P<0.001 versus WT control. (b) Semi-quantitative PCR analysis of Igk rearrangement in small pre-B cells of WT and Brwd1mut mice (n=3). (c) Quantitative analysis of Vκ-Jκ rearrangement presented in “b” (n=3). *P<0.001 versus WT Vκ-Jκ1–5 (unpaired t-test). (d) Quantitative RT-PCR for Vκ-Jκ1 recombination in small pre-B cells of WT and Brwd1mut mice and IgM+ splenic B cells (n=3). *P<0.001 versus WT Vκ-Jκ1 (unpaired t-test). (e,f) Quantitative RT-PCR for expression of Brwd1 (e) or κGT (f) in Irf4−/−Irf8−/− pre-B cells expressing mock (shRNA targeting firefly luciferase) or Brwd1-shRNA cultured in presence (+IL-7, 10ng/ml) and absence (-IL-7; 0.1ng/ml) of IL-7 for 48 hours (n=3).*P<0.001 (in e and f) versus +IL-7 mock-shRNA expressed cells. **P<0.001 (in e and f) versus –IL-7 mock-shRNA expressed cells (unpaired t-test). (g) Semi-quantitative PCR analysis of Igk rearrangement in Irf4−/−Irf8−/− pre-B cells expressing mock or Brwd1-shRNA cultured in presence and absence of IL-7 for 48 hours (representative of three experiments). (h) Quantitative analysis of Vκ-Jκ rearrangement presented in “g”. *P<0.001 versus –IL-7 mock-shRNA expressed cells (n=3, unpaired t-test). (i) Quantitative RT-PCR for Vκ-Jκ1 recombination in Irf4−/−Irf8−/− pre-B cells expressing mock-shRNA or Brwd1-shRNA cultured in presence and absence of IL-7 for 48 hours (n=3). *P < 0.001 versus mock-shRNA Vκ-Jκ1 (unpaired t-test). All bar graphs are presented as average ±s.d..

To confirm that BRWD1 was required for Igk recombination we used Irf4−/−Irf8−/− pre-B cells, which rapidly proliferate in vitro with IL-7 and undergo Igk recombination upon IL-7 withdrawal9. IL-7 withdrawal robustly induced expression of Brwd1 (Fig. 4e). We then used retrovirus to express a shRNA targeting Brwd1, or a shRNA control, in cultured Irf4−/−Irf8−/− pre-B cells. In the presence of IL-7, both Brwd1 and κGT were low and this was not affected by the Brwd1 specific shRNA (Fig. 4e, f). However, upon IL-7 withdrawal the induction of Brwd1 was reduced approximately by 75% and κGT by 55% in Irf4−/−Irf8−/− pre-B cells expressing the Brwd1 specific shRNA (Fig. 4e, f). In contrast, Igk recombination following IL-7 withdrawal was attenuated by 5-fold in Irf4−/−Irf8−/− cells expressing the Brwd1 specific shRNA (Fig. 4g–i). Therefore, both in vivo and in vitro studies indicate a critical role for BRWD1 in Igk recombination.

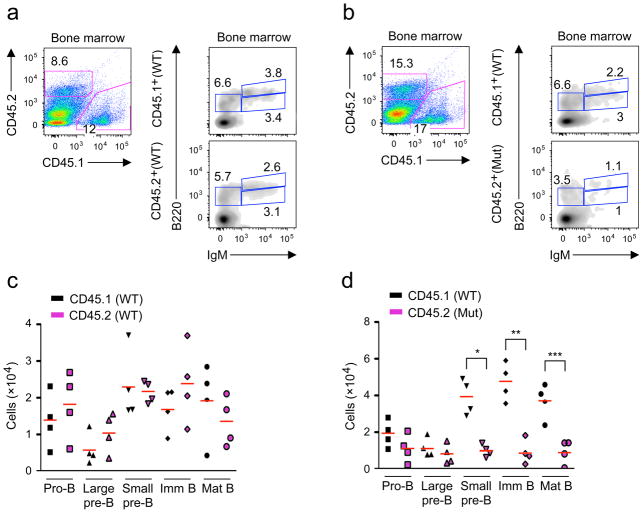

BRWD1 is recruited to histone H3K9AcS10pK14Ac marks at Igk

In vitro studies of the BRWD1 bromodomains predict recruitment to H3K9Ac, phosphorylated H3S10 (H3S10p) and H3K14Ac27. Therefore, pro-B and small pre-B cells were isolated from wild-type BM by flow sorting and nuclear preparations were subjected to chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with H3K9Ac, H3S10pK14Ac or BRWD1 specific antibodies followed by qPCR for the indicated regions of the Igk locus including the 3′ enhancer (3′Eκ) (Fig. 5a–c). In pro-B cells, the Igk locus was essentially devoid of detectable H3K9Ac or H3S10pK14Ac epigenetic marks. However, upon transit into the small pre-B cell pool, there was a robust induction of H3K9Ac and H3S10pK14Ac through Jκ, Eκi and Cκ (Fig. 5a, b). Remarkably, BRWD1 was preferentially recruited to the Jκ through Cκ regions marked with both H3K9Ac and H3S10pK14Ac (Fig. 5c). Jκ segments were negligible in chromatin immunoprecipitations with BRWD1-specific antibodies from Brwd1mut small pre-B cells (Supplementary Fig. 4a).

Figure 5.

BRWD1 is recruited to Igk marked with H3K9Ac and H3S10pK14Ac. (a,b,c) ChIP-qPCR with IgG, H3K9Ac (a) H3S10pK14Ac (b) and BRWD1(c) specific antibodies in flow-sorted WT pro-B and small pre-B cells for indicated regions of Igk (Supplementary Table 1). *P<0.001 versus pro-B cells in respective region (unpaired t-test). (d) ChIP-qPCR with IgG and H3S10p specific antibodies in Irf4−/−Irf8−/− pre-B cells expressing empty vector (Mock), DN-Ras or DN-MEK. Cells were cultured for 48 hours in presence or absence of IL-7. *P<0.001 versus mock -IL-7 H3S10p (unpaired t-test). (e) ChIP-qPCR with IgG and H3S10p specific antibodies in Irf4−/−Irf8−/− pre-B cells expressing a retrovirus-encoded fusion of the estrogen receptor and inducible Id3 (ER-Id3) and cultured for 48 h in presence or absence of IL-7 and mock-treated (uninduced; left) or induced for 48 h with 1 μM tamoxifen (Induced; right). (f,g) ChIP-qPCR with IgG, H3K9Ac (f) or H3K14Ac (g) specific antibodies in Irf4−/−Irf8−/− pre-B cells expressing inducible Id3 (ER-Id3) and cultured for 48 h in presence or absence of IL-7 and mock-treated (uninduced; left) or induced for 48h with 1 μM tamoxifen (Induced; right). *P<0.001, versus uninduced -IL-7 H3K9Ac (f) and uninduced -IL-7 H3K14Ac (g) (unpaired t-test). (h) ChIP-qPCR with IgG and BRWD1 specific antibodies in Irf4−/−Irf8−/− pre-B cells expressing empty vector, DN-Ras or DN-MEK. Cells were cultured for 48 hours in presence or absence of IL-7. *P<0.001 versus mock -IL-7 BRWD1 (unpaired t-test). (i) DNase I hypersensitivity profiles from Jκ to Cκ region of Igk in pro-B and splenic B cells presented as smoothed read density (mm9 chromosome 6: 70,672,550 to 70,676,748). (j) ChIP with IgG or H3K16Ac specific antibodies from flow sorted pro-B, small pre-B and splenic B cells followed by quantitative PCR with non-overlapping primer sets designed to detect indicated Igk regions. *P<0.001, versus WT small pre-B H4K16Ac (unpaired t-test). Data are representative of three independent experiments (average ±s.d).

It is possible that BRWD1 decorates Igk with H3K9Ac and H3S10pK14Ac. Therefore, nuclear lysates from wild-type and Brwd1mut small pre-B cells were subjected to ChIP-qPCR with H3K9Ac or H3S10pK14Ac-specific antibodies as described above. The absence of BRWD1 in small pre-B cells did not substantially change the magnitude of either H3K9Ac or H3S10pK14Ac at the Igk locus (Supplementary Fig. 4b, c). These data suggest that BRWD1 is recruited to a pre-existing, specific epigenetic landscape.

Erk induces H3S10 phosphorylation at Igk

The pre-BCR activates Erk10 which can directly phosphorylate H3S10 (refs. 31,32). Therefore, we determined if blocking the Erk pathway in Irf4−/−Irf8−/− cultured cells diminished H3S10 phosphorylation. With IL-7 there was modest H3S10 phosphorylation at Jκ, Eκi and Cκ (Fig. 5d) that increased following IL-7 withdrawal. This induction was greatly attenuated in Irf4−/−Irf8−/− cells expressing either dominant-negative Ras (DN-Ras) or DN-MEK (Fig. 5d). We next examined if H3S10 phosphorylation could be a consequence of E2A induction. Irf4−/−Irf8−/− cells expressing an estrogen receptor (ER)-Id3 fusion were cultured in the presence or absence of 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen10. However, inhibiting E2A did not appreciably diminish Igk H3S10 phosphorylation (Fig. 5e).

We next examined if E2A was specifically required for Igk H3K9Ac and H3K14Ac. Irf4−/−Irf8−/− cells expressing ER-Id3 were cultured as above and assayed by ChIP with H3K9Ac and H3K14Ac specific antibodies. Withdrawal of IL-7 induced robust H3K9Ac and H3K14Ac at Jκ through Cκ (Fig. 5f, g) which were significantly attenuated by Id3. Finally, we determined if Erk activation was needed for BRWD1 recruitment. Expression of DN-Ras or DN-MEK in Irf4−/−Irf8−/− cells diminished BRWD1 recruitment to Igk following IL-7 withdrawal (Fig. 5h). Overall, these observations suggest that downstream of the pre-BCR, Erk signaling sets the epigenetic landscape at Igk to recruit BRWD1.

BRWD1 regulates Igk locus accessibility

Reanalysis of pro-B and splenic B (CD19+) DNase-Seq data33,34 demonstrated that the Jκ to Cκ regions of the Igk locus were inaccessible in pro-B while they were accessible in splenic B cells (Fig. 5i). We next assessed if BRWD1 played a role in opening the Igk locus in small pre-B cells. Nuclear lysates from flow isolated wild-type and Brwd1mut pro-B, small pre-B and splenic B cells were subjected to ChIP with H4K16Ac specific antibodies35. In wild-type pro-B cells, there was little H4K16Ac at the Igk locus. However, on transition to the small pre-B cell stage H3K16Ac became robust at Igk (Fig. 5j). In contrast, in Brwd1mut small pre-B cells, this mark was almost absent. These data suggest that BRWD1 binds to Igk and facilitates chromatin decompaction.

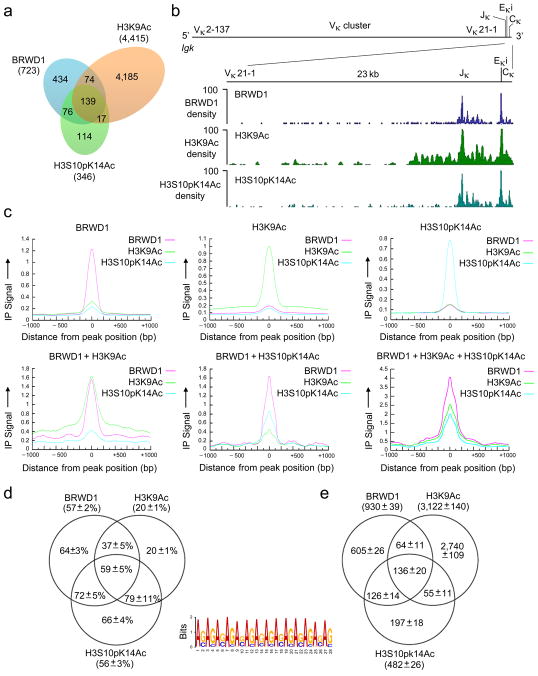

BRWD1 is recruited to H3K9Ac and H3S10pK14Ac genome-wide

We next assessed the relationships between H3K9Ac, H3S10pK14Ac and BRWD1 recruitment across the entire genome. Nuclear preparations from wild-type flow-sorted small pre-B cells were subjected to ChIP as above followed by massively parallel deep sequencing (ChIP-Seq). Alignment to the genome of ChIP-Seq data demonstrated that over 62% of H3S10pK14Ac peaks were co-incident with BRWD1 peaks (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Fig. 5a). Over 64% of these overlapping peaks were also co-incident with H3K9Ac. Concordance of BRWD1, H3K9Ac and H3S10pK14Ac peaks at the Igk locus was particularly good with peaks clustered at Jκ and Eκi (Fig. 6b). Comparison of genome-wide normalized immunoprecipitation signal distributions for BRWD1, H3K9Ac and H3S10pK14Ac confirmed extensive peak overlap (Fig. 6c). Considering either each ChIP-Seq data set separately, or in combination, 37% to 62% of peaks were in gene regulatory regions (intragenic or promoter) and 38% to 63% were intergenic (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

Figure 6.

Recruitment of BRWD1 to H3K9Ac and H3S10pK14Ac genome-wide. (a) Overlap of peaks (P<10−7) obtained by ChIP-Seq for BRWD1, H3K9Ac and H3S10pK14Ac from purified WT small pre-B cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (b) ChIP-Seq analysis of the binding of BRWD1, H3K9Ac and H3S10pK14Ac at the Igk locus in purified WT small pre-B cells presented as smoothed density (where ‘density’ indicates sequence ‘read’). Data are representative of two independent experiments. Igk locus shows the location of Vκ, Jκ, Eκi and Cκ gene segments (mm9 chromosome 6: 70,653,572–70,676,748). (c) Alignment of BRWD1, H3K9Ac and/or H3S10pK14Ac enrichment in ChIP-Seq peaks. Y-axis represents normalized immunoprecipitation signal distribution for ChIP peaks centered at 0 bp. (d) Percentage of peaks containing at least one extended GAGA motif (GA11). The +/− errors are standard deviations from 100 bootstrapping runs for each peak group. (e) Total number of extended GAGA motif (GA11) hits in different ChIP-Seq groups. The +/− errors are standard deviations from 100 bootstrapping runs for each peak group.

There was no evidence of BRWD1 binding to Igh or Igl (which encodes the λ light chain) in small pre-B cells (data not shown). Furthermore, JH and Jλ were not marked with H3K9Ac or H3S10pK14Ac. Igl is normally rearranged in a small fraction of immature B cells2. Therefore, we examined if BRWD1 bound Igl in immature B cells from mice that cannot rearrange Igk (Igkdel)36. There was no detectable binding of BRWD1 to Jλ in these cells (Supplementary Fig. 5c). These data indicate that BRWD1 is a specific mediator of Igk recombination in small pre-B cells.

BRWD1 binds at GAGA motifs genome-wide

We next used de novo prediction of motifs to assess DNA sequences occurring at single and co-incident ChIP-Seq peaks. In individual peaks, the most significant DNA motifs observed were similar to ISRE (BRWD1 and H3S10pK14Ac) and Sox12 (H3K9Ac) binding motifs, both of which contain repetitive GA (CT) elements (Supplementary Fig. 5d). At peaks co-incident in two or more ChIP-Seq data sets, long repetitive sequences of GAGA were overrepresented (BRWD1/H3S10pK14Ac, P<10−5993 and BRWD1/H3K9Ac/H3S10pK14Ac, P < 10−2640) (Supplementary Figs. 5e, f). Further analysis demonstrated that extended GAGA motifs (GA11) were most enriched in BRWD1 and H3S10pK14Ac peaks with a prevalence of up to 79% (Fig. 6d). In some data sets, the total number of extended GAGA motifs exceeded the total number of peaks (Fig. 6e) indicating that some peaks contained multiple GAGA motifs. These data demonstrate a remarkable enrichment of GAGA motifs at sites of H3S10pK14Ac and BRWD1 recruitment.

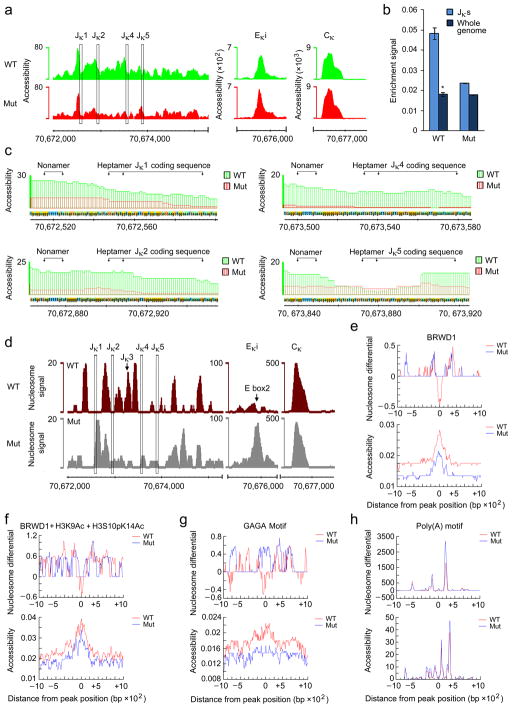

BRWD1 regulates accessibility and nucleosome positioning

In Drosophila, GAGA motifs recruit Trithorax-like (TRL)which regulates gene accessibility37,38. Therefore, to determine if BRWD1 regulates gene accessibility genome-wide, nuclear lysates from flow-sorted wild-type and Brwd1mut small pre-B cells were assessed by transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-Seq)39. Comparison at the Igk locus in Brwd1mut small pre-B cells revealed diminished accessibility at the Jκ region with relatively little change in overall accessibility at the Eκi and Cκ regions (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Table 2). The Jκ region was approximately 2.7 times more accessible in wild-type small pre-B cells compared to whole genome average accessibility. In contrast, the Jκ region in Brwd1mut small pre-B cells was only 1.3 times more accessible (Fig. 7b). Genome-wide, accessibility was similar in wild-type and Brwd1mut small pre-B cells while the number of accessible regions in Brwd1mut small pre-B cells was increased (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Indeed, some genes such as Ccnd3 were more accessible in Brwd1mut versus wild-type small pre-B cells (Supplementary Fig. 6b).

Figure 7.

BRWD1 regulates chromatin accessibility and nucleosome positioning in vivo. (a) Accessibility (open chromatin) at Jκ, Eκi and Cκ in WT and Brwd1mut small pre-B cells. y-axis represents tags per million reads. Data are representative of two independent experiments (105 cells/sample). (b) Quantitative measurement of accessibility in Jκ region and whole genome of WT and Brwd1mut small pre-B cells. Jκ region was defined as 70,672,000–70,675,000 of chromosome 6 (mm9). *P<0.0001, versus whole genome average accessibility (unpaired t-test). (c) Accessibility around individual Jκ segments at single nucleotide resolution in WT and Brwd1mut small pre-B cells. The recombination signal sequences (RSS), nonamer (G/AGTTTTTGT) and heptamer (CACTGTG) motifs and the coding sequences of each Jκ are provided. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (d) Nucleosome positioning at Jκ, Eκi and Cκ in WT and Brwd1mut small pre-B cells. Nucleosome signal represents the difference in normalized densities between the simulated signal and background data obtained from the same data; “signal” is from read pairs with large insert sizes, and “background” is from read pairs with short insert sizes. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (e–h) DNA foot printing analysis of ±1kb region for WT (red) and Brwd1mut (blue) small pre-B cells at BRWD1 peaks (e), BRWD1+H3K9Ac+H3S10pK14Ac peaks (f), GAGA motifs (n=136) (g) and poly(A) motifs (n=737) (h) centered at 0. In each of (e), (f), (g) and (h) ‘Nucleosome differential’ (top) and ‘Accessibility’ (bottom) were demonstrated. For nucleosome differential (y-axis), values above 0 indicate the presence of a nucleosome while values below 0 tend to be nucleosome free. x-axis is distance in bp from indicated peak or motif.

Extensive recombination at Igk could distort apparent accessibility. However, comparison of Igk in Rag1−/− pro-B cells, wild-type small pre-B cells, and splenic B cells revealed that Vκ segment accessibility was similar in Rag1−/− pro-B cells and wild-type small pre-B cells (Supplementary Fig. 7c–e). In contrast, apparent accessibility throughout Igk was greatly diminished in splenic B cells. Therefore, in small pre-B cells, Jκ was poised for recombination but substantial recombination had not yet occurred.

In Brwd1mut small pre-B cells there was greatly diminished accessibility at each RSS and at the exons encoding Jκ1, Jκ2 and Jκ4 compared to wild-type small pre-B cells (Fig. 7c). For Jκ5, the loss of accessibility observed in Brwd1mut small pre-B cells was most prominent at the RSS nonamer motif. In contrast, changes in accessibility at Eκi were subtle, with a slight overall shift in the distribution of accessibility (Fig. 7a).

It has been postulated that nucleosomes must flank recombining Jκ segments as RAG2 is recruited to H3K4me3 (ref. 15). As predicted, in wild-type small pre-B cells, nucleosomes were positioned between Jκ segment exons leaving the RSSs and Jκ segments nucleosome free (Fig. 7d and Supplementary Fig. 7a). In marked contrast, in Brwd1mutsmall pre-B cells, nucleosomes were positioned over each RSS and Jκ segment. Furthermore, while in wild-type small pre-B cells Eκi was primarily free of nucleosomes, in Brwd1mut cells there was accumulation of nucleosomes over the E2A binding site E box2 (Fig. 7d). Interestingly, at 3′ Eκ, there was also an accumulation of nucleosomes in Brwd1mut small pre-B cells (Supplementary Fig. 7b), suggesting that BRWD1 might regulate nucleosome organization through long-range loops40.

Genome-wide, BRWD1 binding was associated with nucleosome depletion (Fig. 7e, top) and enhanced DNA accessibility (Fig. 7e, bottom). Likewise, BRWD1/H3K9Ac/H3S10pK14Ac peaks were locally associated with nucleosome free DNA (Fig. 7f). These associations were also observed inBRWD1/H3S10pK14Ac and H3S10pK14Ac peaks but not in the BRWD1/H3K9Ac or H3K9Ac peaks (Supplementary Fig. 7c). The largest effect of BRWD1 on nucleosome placement was observed at extended GAGA motifs that were enriched in BRWD1, H3K9Ac and H3S10pK14Ac (Supplementary Fig. 7d). These extended GAGA motifs were normally relatively free of nucleosomes in wild-type small pre-B cells while in Brwd1mut cells, nucleosomes tended to occupy these motifs (Fig. 7g). No change in nucleosome positioning, or gene accessibility, was observed at control poly-A motifs found in single and in co-incident peaks (Fig. 7h).

TRL can productively bind 5-nucleotide-long GAGAG motifs41. Such motifs were found within 140 bp upstream of the nonamer sites for Jκ1, Jκ2, Jκ4 and Jκ5 (Supplementary Fig. 7e). Strikingly, no GAGAG motif was found upstream of the non-functional exon Jκ3 where nucleosomes accumulate in wild-type small pre-B cells. Two GAGAG motifs were also found in Eκi (Supplementary Fig. 7e). These data demonstrate that BRWD1, in a H3S10pK14Ac and GAGA motif-associated manner, regulates both chromatin accessibility and precise nucleosome positioning.

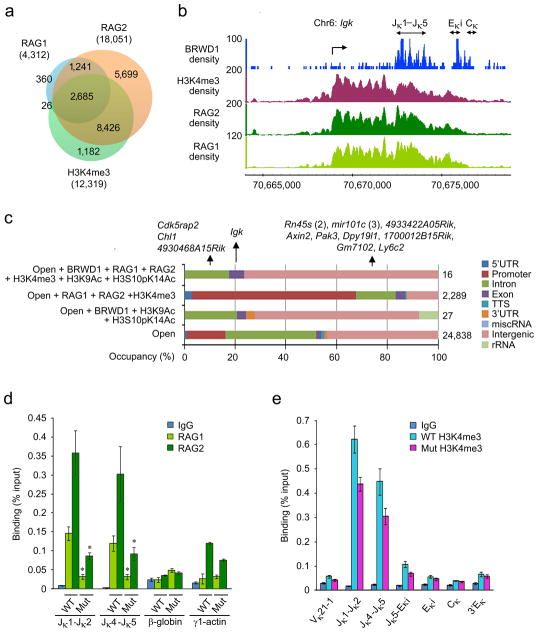

RAG1 and RAG2 recruitment to Igk requires BRWD1

We next examined the inter-relationships between BRWD1, RAG1 and RAG2 binding15. For these experiments, we used RAG1, RAG2 and H3K4me3 ChIP-Seq data sets23 from pre-B cells isolated from Rag1−/− × B18i-Igh knock-in × RAG1(D708A)-transgenic mice which arrest development at the small pre-B cell stage with non-productive RAG complexes bound to chromatin15. Both RAG1 and RAG2 bind permissively across the genome with 2685 RAG1/RAG2/H3K4me3 co-incident peaks (Fig. 8a). We next examined if BRWD1 could play a role in targeting RAG to Igk. Analysis at Igk revealed RAG1 and RAG2 binding at Jκ that extended proximally to the κGT transcription start site (TSS) (Fig. 8b). In contrast, BRWD1 binding was primarily restricted to Jκ (Fig. 8b), which has been proposed to be the center for Vκ to Jκ recombination1.

Figure 8.

BRWD1 is required for RAG1 and RAG2 recruitment to Igk. (a) Overlap of RAG1, RAG2 and H3K4me3 ChIP-Seq peaks (P<10−7). (b) Co-incidence of BRWD1, RAG1, RAG2 and H3K4me3 at the Jκ-Cκ region of the Igk locus. (c) Overlap of indicated peaks (Open is accessible by ATAC-Seq) with RAG1, RAG2 and H3K4me3 with distribution of peaks within regions of DNA given. Total number of peaks in a particular group was shown at right. (d) ChIP-qPCR for RAG1 and RAG2 at Jκ, β-globin, and Actg1 (γ1-actin) genes in WT and Brwd1mut small pre-B cells (n=3). *P<0.001, versus WT small pre-B RAG1/RAG2 (unpaired t-test). (e) ChIP-qPCR with H3K4me3 specific antibodies or control IgG from flow-sorted WT pro-B and small pre-B cells to detect various regions of Igk (n=3). All bar graphs are presented as average ±s.d.

Genome-wide, the overlap between BRWD1/H3K9Ac/H3S10pK14Ac and RAG1/RAG2/H3K4me3 at open chromatin (Fig. 8c) was very restricted with only 16 co-incident peaks occurring near 13 genes. At only four of these genes was binding intragenic and at only one (Igk) was binding at exons. Furthermore, only the Jκ peak contained RSS sites. Cryptic RSSs were found in four of these 16 peaks (Supplementary Table 3). However the putative heptamer motif in all began with CAT, instead of the canonical CAC. Such cryptic RSSs are usually not functionally active (unpublished observation).

Interestingly, only 10 of the above 16 co-incident peaks exhibited BRWD1-dependent remodeling of chromatin (data not shown and Supplementary Table 3). We postulated that this might reflect the availability of GAGAG motifs within these peaks. Indeed, all 10 peaks at which chromatin remodeling occurred had at least one GAGAG motif while none of the 6 other peaks did.

Finally, we asked whether BRWD1 played a role in RAG recruitment to Igk. Nuclear preparations from wild-type and Brwd1mut small pre-B cells were subjected to ChIP with RAG1- or RAG2-specific antibodies followed by qPCR for Jκ1-Jκ2 and Jκ4-Jκ5 regions. Both RAG1 and RAG2 recruitment were reduced approximately 4-fold in Brwd1mut small pre-B cells as compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 8d). In contrast, RAG2 recruitment to Actg115 was similar. Rag1 and Rag2 expression were only slightly diminished in Brwd1mut small pre-B cells (Supplementary Fig. 7f). Furthermore, the expression of other genes implicated in pre-B cell proliferation and Igk recombination, including Tcfe2a (encoding E2A), Pax5, Ikzf1 (Ikaros), Irf4/Irf8, Smarca4 (BRG1) and Myc were not significantly altered in Brwd1mut small pre-B cells as compared to wild-type cells (Supplementary Fig. 7g). RAG2 binds H3K4me3 and therefore decreased RAG recruitment might reflect diminished nucleosome occupancy or methylation. However, there was only a modest decrease (30%) in H3K4me3 across Igk in Brwd1mut small pre-B cells (Fig. 8e). Therefore, H3K4me3 does not appear to be sufficient to recruit RAG2 to Jκ, but requires BRWD1 for efficient RAG protein binding.

DISCUSSION

Numerous findings have indicated that accessibility of the antigen receptor genes to recombination, and recruitment of the RAG proteins, is required for recombination4,13. However, recent evidence has also made it clear that usual mechanisms of accessibility are not sufficient to explain the cell lineage and stage-specific recombination of antigen receptor loci1. In small pre-B cells, both RAG1 and RAG2 are recruited to thousands of genes most of which are accessible and bear the usual marks of open chromatin15,23. However, under physiological conditions, only Igk is targeted for recombination in these cells. Herein, we demonstrate that a complex, lineage and stage-restricted mechanism specifically remodels the chromatin landscape at Jκ to enable assembly of the RAG protein complex at RSS sites poised for recombination.

Central to productively assembling the recombination machinery at Jκ, and opening the Igk locus to recombination, is BRWD1. Like κGT, Brwd1 transcription is repressed by STAT5 yet rapidly induced following loss of IL-7R signaling. Subsequent targeting of BRWD1 is mediated by a very specific and relatively genome-wide restricted, epigenetic code that is dependent upon pre-BCR signaling. Downstream of the pre-BCR, activation of Erk induces H3S10 phosphorylation; a possible direct substrate of Erk31,32. Interestingly, Erk can be directly recruited to GAGA motifs42 providing a possible mechanism for the observed increase in H3S10p at GAGA-enriched DNA sequences. Erk also induces free nuclear E2A that binds and recruits histone acetyltransferases to Eκi where they acetylate regional histones at H3K9 and H3K14 (refs 9,11). This specialized epigenetic code largely restricts BRWD1 to the putative recombination center at Jκ. In contrast, the RAGs, which are recruited to general features of open chromatin, are broadly recruited to the region from which κGT is transcribed. The coordinated control of BRWD1 expression and recruitment by the IL-7R and pre-BCR respectively ensure that Igk recombination is restricted to small pre-B cells and follows Igh recombination2.

Remarkably, BRWD1 was required for the positioning of nucleosomes relative to GAGA-motifs genome-wide. While long GAGA motifs were highly enriched at BRWD1 sites, five nucleotide GAGA motifs were found 5′ to each functional Jκ segment. In Drosophila, five nucleotide GAGAG motifs can recruit TRL41, which enhances gene accessibility to transcription factors37. It has been postulated that TRL travels along GAGAG motifs to slide or eject nucleosomes38, functions consistent with what we observed with BRWD1. Only one known mammalian molecule shares sequence homology with TRL, ThPOK (cKrox)43. However, ThPOK has not been demonstrated to position nucleosomes in a GAGA-dependent manner. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, BRWD1 is the first mammalian protein associated with TRL-like functions.

That the specific chromatin remodeling events associated with BRWD1 should enable RAG-mediated recombination is predicted by previous in vitro studies1,16,17,44. Overall accessibility at Jκ was increased by BRWD1 yet the most marked and consistent increase was at the Jκ RSS nonamers which have been proposed to be the initial sites of RAG1 recruitment1,44,45. Importantly, BRWD1 was also required for the precise positioning of nucleosomes flanking the RSSs and Jκ exons. This is predicted to both enable H3K4me3-mediated RAG2 recruitment and to help position the RAG complex at the RSSs.

Our data suggest that there are important differences in the accessible states associated with enhanced transcription versus those that enable Ig recombination. Transcription is usually associated with nucleosome positioning at transcription start sites and a relative depletion of nucleosomes at exons46. However, BRWD1 binding resulted in precise placement of nucleosomes flanking RSSs and Jκ exons, changes that would not necessarily be reflected in transcriptional changes. Indeed, κGT was only decreased two-fold in Brwd1mut pre-B cells despite large differences in nucleosome positioning throughout the Jκ region and greatly diminished Igk recombination. This apparent discrepancy between κGT transcription and Igk recombination suggests that while transcription might be permissive for recombination47, recombination efficiency is not proportional to the magnitude of transcription.

BRWD1 lacks identifiable catalytic domains and it is unlikely that it directly mediates nucleosome positioning or other BRWD1-associated functions such as acetylation of H4K16. Rather, we propose that BRWD1 serves as a platform that binds to specific epigenetic landscapes where it assembles and coordinates the activities of other chromatin regulators. BRWD1 can recruit the ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling protein SMARCA4 (BRG1)28, the catalytic subunit of the mammalian SWI/SNF complex. In vivo, SMARCA4 binds Ig segments when they are accessible to RAG1/2 and is required for recombination48,49. Other binding partners of BRWD1 remain to be identified.

It appears that other molecules or processes can partially compensate for BRWD1 deficiency. B lymphopoiesis was not ablated in Brwd1mut mice and in those B cells able to transit into the periphery there was some restoration of H4K16Ac at Jκ. There are two BRWD1 paralogs in the mouse genome, pleckstrin homology interacting protein PHIP and BRWD3. Like, BRWD1, both PHIP and BRWD3 contain WD40 repeats and tandem BROMO domains. Both have over 60% amino acid sequence homology with BRWD1 through large N-terminal domains29 and both are expressed in developing B lymphocytes. However, neither PHIP nor BRWD3 expression is induced in pre-B cells and Jκ chromatin structure was remarkably aberrant in Brwd1mut mice. These observations suggest that BRWD1, and BRWD1-associated molecules, are the major determiners of Jκ chromatin structure in small pre-B cells.

Our studies demonstrate that opening the Igk locus to recombination requires coordinated regulation of stage-specific signaling processes and the induction of BRWD1 whose expression is highly restricted. These findings raise the possibility that those molecules regulating recombination at other antigen receptor loci, including, Igh, Igl, Tcrb and Tcra, will also be specialized, developmentally restricted and tightly regulated by signals critical for key developmental transitions. We postulate that such layers of unique combinatorial specificities would ensure that antigen receptor gene recombination is sequential and only occurs in correct developmental contexts.

METHODS

Mice

Wild-type (C57BL/6 and C57BL/6 backcrossed to C3HeB/FeJ), Irf4−/−Irf8−/− (C57BL/6), Brwd1mut (C57BL/6-C3HeB/FeJ) and Rag1−/− (C57BL/6) and Igkdel (BALB/c) mice were housed in the animal facilities of the University of Chicago. Rag1−/−, Rag2−/−, Rag1−/−B18i Igh-knock-in with RAG1(D708A) transgenic and Rag1−/−B18i Igh-knock-in (C57BL/6-129) mice were housed in the animal faci lity of the Yale University. Mice were used at 6–12 weeks of age and experiments were in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Chicago.

Isolation, culture and flow cytometry of bone marrow B cell progenitors

Bone marrow (BM) was collected from wild-type mice and cells were resuspended in staining buffer (3% (vol/vol) FBS in PBS). Erythrocytes were lysed and cells were stained with antibodies specific for CD11c (HL3), NK1.1 (PK136), TCRβ (H57-597), CD71 (C2), Ter119 (TER-119), Mac-1 (M1/70), Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), CD34 (RAM34), Sca1 (Ly-6A/E, D7), c-Kit (CD117, 2B8), Flt3 (CD135, A2F10.1), IL-7Rα (CD127, SB/199), CD4 (H129.19), CD8 (53-6.7), CD25 (IL-2Rα, 7D4), CD44 (IM7), TCRγδ (GL3), CD43 (S7), IgM (R6-60.2), IgD (11–36), CD19 (1D3), B220 (RA3-6B2l), CD93 (AA4.1), CD21 (7G6) and/or CD23 (B3B4); (all from BD Biosciences). Antibodies were directly coupled to fluorescein isothiocyanate, phycoerythrin, phycoerythrin-indotricarbocyamine, allophycocyanin, eFluor 450 or biotin. Pro-B cells (Lin−CD19+B220+CD43+IgM−), large pre-B cells (Lin−B220+CD43−IgM−FSChi), small pre-B cells (Lin−B220+CD43−IgM−FSClo), immature B cells (Lin−B220+CD43−IgM+) and recirculating mature (Lin−B220hiCD43−IgM+) were isolated by cell sorting with a FACSAriaII (BD).

Irf4−/−Irf8−/− pre-B cells were isolated from BM with a MACS separation column (MiltenyiBiotec) for isolation of CD19+ cells. Irf4−/−Irf8−/− pre-B cells (>99% pure) were overlaid on OP9 stromal cells in complete medium with IL-7 at a concentration of 10 ng/ml (high IL-7) or 0.1 ng/ml (low)10.

Short-hairpin RNA

Oligonucleotides of shRNA specific for Brwd1 (97 bases; targeting sequences, Supplementary Table 1) were designed according to the RNAi Consortium criteria and software (Broad Institute: http://www.broadinstitute.org/rnai/public/) and through the use of Ravi Lab Resources (http://katahdin.cshl.org/siRNA/RNAi.cgi?type=shRNA). These shRNA oligonucleotides were cloned into a GFP-expressing retroviral vector based on microRNA miR309.

Retroviral gene transduction

cDNAs encoding mouse DN-Ras (RasN17N), DN-MEK (MEKK1-8E-K97M) or human ER-Id3 were subcloned into the plasmid MIGR110. Retroviruses containing constructs including shRNA targeting Brwd1 were produced by transient transfection of PLAT-E packaging cell lines. After 48 h, GFP+ cells were isolated by cell sorting and were cultured in complete medium. Id3 was induced by treatment of cultures with 1μM 4-OH–tamoxifen for 48 h before assay10.

In vivo reconstitutions

Lineage-depleted LSK progenitors (Lin−Sac1+c-Kit+) from bone marrow of WT C57BL/6 CD45.1+, C57BL/6 CD45.2+ and Brwd1mut CD45.2+ mice were isolated by flow sorting. Then for competitive reconstitution, WT C57BL/6 CD45.1+ LSKs were mixed with either WT C57BL/6 CD45.2+or Brwd1mut CD45.2+ at a ratio of ratio of 1:1 and transferred into sublethally irradiated (550RAD) Rag2−−/−Il2rg−/− recipients by retro-orbital injection. Reconstitution of bone marrow and spleen were analyzed by staining of cells with antibodies to B220, CD19, CD43, IgM, CD4 and CD8 as described before30.

Quantitative PCR analysis

Total cellular RNA was isolated with an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and RNA was reverse-transcribed with SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). For quantitative PCR, a total volume of 25 μl containing 1 μl cDNA template, 0.5 μM of each primer (Supplementary Table 1) and SYBR Green PCRMaster Mix (Applied Biosystems) was analyzed in quadruplicate. Gene expression was analyzed with an ABI PRISM 7300 Sequence Detector and ABI Prism Sequence Detection Software version 1.9.1 (Applied Biosystems). Results were normalized by division of the value for the test gene by that obtained for B2m.

Cell-cycle analysis

B cell progenitors of different developmental stages were flow sorted and then were incubated in a solution containing propidium iodide. The analysis was performed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson) as described10. The proportion of cells in the G1, S and G2-M phases of the cell cycle was analyzed with FlowJo and Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson).

Apoptosis assays

Apoptosis was evaluated via flow cytometry using fluorescently conjugated annexin V (BD Pharmingen). Upon the completion of cell surface staining, the cells were washed and incubated in annexin V binding buffer with annexin V at a 1:20 dilution for 20 min at 25 °C. The cells were then washed, resuspended in annexin V binding buffer, and analyzed by flow cytometry immediately. Annexin V staining was done in conjunction with the vital dye 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) to differentiate early apoptosis (annexin V+7-AAD−) from late apoptosis/necrosis (annexin V+7-AAD+).

PCR analysis of Igk rearrangements

Semi-quantitative PCR with genomic DNA was done as described10 (primers, Supplementary Table 1). For PCR analysis of Igk rearrangements, small pre-B cells from WT and Brwd1mut mice or Irf4−/−Irf8−/− pre-B cell populations (cultured for 48 h in high or low IL-7) were used. Degenerate Vκ and Igk intron primers10, and five-fold template dilutions were used for PCR. A region in Eκi was amplified to control for the amount of genomic DNA (primers Eκi-F and Eκi-R). DNA from wild-type splenic IgM+ B cells was used as positive control. The intensity of the band for each rearrangement product was divided by that for the corresponding Igk intron fragment, followed by normalization to values obtained from IgM+ B cells, given a value of 1. Quantitative analysis of Vκ-Jκ1 rearrangement was performed by qPCR (primers degVκ and κ-J1-R; Supplementary Table 1) using Eκi primers product as a control.

Analysis of Jκ usage

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) for flow-sorted small pre-B cells from WT and Brwd1mut mice. cDNA was synthesized as described above. Vκ-Jκ rearrangements were amplified by PCR using high fidelity Taq enzyme (Roche) with specific primers (Supplementary Table 1). PCR amplicons were then cloned using the TOPO-TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) and sequenced (UC-core facility). Unique sequences were analyzed for Jκ usage.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

A ChIP assay kit was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Millipore 17-295)9. Samples were immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific for H3K9Ac (Millipore 06-942, Lot#2279810), H3S10pK14Ac (Millipore 07-081, Lot#2200929), BRWD1 (E-15; sc-83517, Lot#J1508), H3S10p (Millipore, 06-570, Lot#2202541), H4K16Ac (Millipore 07-329, Lot#2073125), H3K4me3 (Millipore 07-473, Lot# 2430389), rabbit IgG (011-000-003; Jackson Immunoresearch Labs), RAG1 orRAG215. Purified DNA was then analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR primers (Supplementary Table 1).

ChIP-Sequencing

Chromatin from flow sorted small pre-B cells (4–7 ×107) was used for each ChIP experiment with H3K9Ac, H3S10pK14Ac and BRWD1specific antibodies described above. DNA libraries were prepared from the sheared chromatin (200–600bp). Libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq2000. The sequences were aligned to the mm9 reference genome (National Center for Biotechnology Information build mm9_NCBI_build_37.1) with Bowtie alignment software, and only reads with unique matches were retained.

ChIP-Seq peak calling and motif analysis

Peaks for ChIP-Seq samples were called using MACS2at a P-value threshold of 10−7. Peak groups were generated by considering overlapping peak regions of at least 10 bp. HOMER software (hypergeometric optimization of motif enrichment) for de novo motif discovery and next-generation sequencing analysis was used for new prediction of motifs in the peaks. Additionally, de novo motif searches were performed independently on each peak group using meme, asking for the top 10 motifs. GA repeat motifs were obtained from a manual filtering of the motifs found by meme.

For further motif analysis and DNA footprinting, peaks were recalled at a P-value threshold of 10−7. We then searched for the GA repeat motifs in each of these peak groups using MAST50, counting both the total number of hits for the motif, and the fraction of sequences with at least one hit for the motif.

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using Sequencing (ATAC-Seq)

ATAC-Seq was performed as recently described39. Briefly, flow-sorted small pre-B cells (1 × 105) from WT and Brwd1mut mice were used for each ATAC-seq. To prepare nuclei, cells were centrifuged at 500g for 5 min, which was followed by a wash with ice-cold PBS and centrifugation at 500g for 5 min. Cells were lysed using cold lysis buffer (10 mMTris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mMNaCl, 3 mM MgCl2 and 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630). Immediately after lysis, nuclei were spun at 500g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatant was carefully pipetted away from the pellet after centrifugation. Immediately following the nuclei prep, the pellet was resuspended in the transposase reaction mix (25μl 2× Tagment buffer, 2.5 μl Tagment DNA enzyme (Illumina, FC-121-1030) and 22.5 μl nuclease-free water. The transposition reaction was carried out at 37 °C for 30 min. Following transposition the sample was purified using a QiagenMinElute kit. Following purification, we amplified library fragments using Nextera PCR Primers (IlluminaNextera Index kit) and NEBnext PCR master mix (New England lab, 0541) for a total of 10–12 cycles followed by purification using a Qiagen PCR cleanup kit.

The amplified, adapter ligated libraries were size selected using Life Technologies’ E-Gel® SizeSelect™ gel system in the 150–650 bp range. The size-selected libraries were quantified using the Agilent Bioanalyzer and via qPCR in triplicate using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit on the Life Technologies Step One System. Libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq2000 system to generate 7.5–10 × 107 50-bp paired-end reads.

QC and DNA alignment

All raw sequence data was quality trimmed to a minimum phred score of 20 using trimmomatic51. Alignment to reference genome mm9 was done with BWA52. For ATAC-Seq data, read pairs where one pair passed quality trimming but the other did not were aligned separately and merged with the paired-end alignments. PCR duplicates were removed using Picard MarkDuplicates and alignments with an edit distance greater than 2 to the reference, or those were mapped multiple times to the reference, were removed.

ATAC-Seq analysis

Read alignment positions were adjusted according to their strand: +4 bp for + strand alignments, and −5 bp for − strand alignments. Open chromatin regions were called using Zinba53 with a window size of 300 bp, an offset of 75 bp, and a posterior probability threshold of 0.8.

For nucleosome positioning, properly paired alignments were filtered by their fragment size. Fragment sizes less than 100 bp were considered nucleosome free and replaced with a single BED region, and used as a background. Sizes between 180 and 247 bp were considered mononucleosomes and replaced with a single BED region; sizes between 315 and 473 bp were considered dinucleosomes and replaced with two BED regions, each spanning half the overall fragment length; and sizes between 558 and 615 bp were considered trinucleosomes and replaced with three BED regions, each spanning one third of the overall fragment length; the mono-, di-, and tri-nucleosome regions were concatenated and used as the nucleosome signal. The resulting BED regions were analyzed using DANPOS54 with the parameters –p 1 –a 1 –d 20 ––clonalcut 0 to identify regions enriched or depleted for nucleosomes.

DNA footprinting data were obtained by combining bigWig enrichment tracks for ChIP-Seq and ATAC-Seq data over specified BED regions (combinations of peak calls or motif hits). ChIP-Seq enrichment data were generated by MACS2, as described above. Open chromatin enrichment data from ATAC-Seq were generated from the read-adjusted alignments using custom scripts, normalized to reads per million alignments, and nucleosome positioning enrichment data were obtained from DANPOS54. DNA footprinting scores were averaged over 10 bp bins from enrichment tracks, using custom scripts.

For correlations between signals, the UCSC genome browser’s bigWigToWig tool was used to extract profiles for the Igk loci from each of the enrichment tracks. Different enrichment profiles were compared using both the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients; the latter was included to prevent regions of very high enrichment from dominating the correlation.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with the unpaired t-test and analysis of variance, followed by the test of least-significant difference for comparisons within and between groups. All categories in each analyzed experimental panel were compared P values below 0.05 were considered significant. All P values below 0.001 were rounded to facilitate comparisons of results.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Olson and D. Leclerc for cell-sorting services; and the ImmGen Consortium for data assembly. We thank W.J Greenleaf (Stanford University) for ATAC-Seq methodology. We also thank O. Kalininafor Igkdel mice. Supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH GM088847, GM101090, AI120715 and U19 AI082724 to M.R.C). D.G.S. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

ChIP-Seq and ATAC-Seq data sets have been deposited in the GEO database with accession number GSE63302.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.M. designed, did and analyzed most of the experiments including ChIP-Seq and ATAC-Seq, oversaw the entire project and wrote the first manuscript draft; K.M.H. assisted M.M. in flow cytometry of some of the experiments, confocal microscopy, immunoblot, shRNA experiments and adoptive transfer studies. A.T. assisted in flow cytometry of some of the experiments; M.M-C. performed the ChIP-Seq and ATAC-Seq analysis with M.M. N.B. worked with M.M-C. G.T. generated the RAG1, RAG2 and H3K4me3 ChIP-Seq data. J.H.T. assisted M.M. in ATAC-Seq methodology development; J.J.B. assisted M.M. in H3S10p ChIP. J.J.E. generated and provided advice about Brwd1mut mice. D.G.S. collaborated with RAG and H3K4me3 ChIP-Seq data; and M.R.C. oversaw the entire project and prepared the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Schatz DG, Ji Y. Recombination centers and the orchestration of V(D)J recombination. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:251–263. doi: 10.1038/nri2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark MR, Mandal M, Ochiai K, Singh H. Orchestrating B cell lymphopoiesis through interplay of IL-7 receptor and pre-B cell receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:69–80. doi: 10.1038/nri3570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang L, Reynolds TL, Shan S, Desiderio S. Coupling of V(D)J recombination to cell cycle suppresses genomic instability and lymphoid tumorigenesis. Immunity. 2011;34:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanhope-Baker P, Hudson K, Shaffer AL, Constantinescu A, Schlissel M. Cell type-specific chromatin structure determines the targeting of V(D)J recombinase activitiy in vitro. Cell. 1996;85:887–897. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yancopoulos GD, Alt FW. Developmentally controlled and tissue-specific expression of unrearranged VH gene segments. Cell. 1985;40:271–281. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abarrategui I, Krangel MS. Regulation of T cell receptor-alpha gene recombination by transcription. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1109–1115. doi: 10.1038/ni1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cobb RM, Oestreich KJ, Osipovich OA, Oltz EM. Accessibility control of V(D)J recombination. Adv Immunol. 2006;91:45–109. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)91002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson K, et al. Regulation of immunoglobulin light-chain recombination by the transcription factor IRF-4 and the attenuation of interleukin-7 signaling. Immunity. 2008;28:335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandal M, et al. Epigenetic repression of the Ig-kappa locus by STAT5-mediated recruitment of the histone methyltransferase Ezh2. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1212–1220. doi: 10.1038/ni.2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandal M, et al. Ras orchestrates exit from the cell cycle and light-chain recombination during early B cell development. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1110–1117. doi: 10.1038/ni.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck K, Peak MM, Ota T, Nemazee D, Murre C. Distinct roles for E12 and E47 in B cell specification and the sequential rearrangement of immunoglobulin light chain loci. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2271–2284. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abarrategui I, Krangel MS. Noncoding transcription controls downstream promoters to regulate T-cell receptor alpha recombination. EMBO J. 2007;26:4380–4390. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krangel MS. T cell development: better living through chromatin. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:687–694. doi: 10.1038/ni1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sikes ML, Meade A, Tripathi R, Krangel MS, Oltz EM. Regulation of V(D)J recombination: a dominant role for promoter positioning in gene segment accessibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12309–12314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182166699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji Y, et al. The in vivo pattern of binding of RAG1 and RAG2 to antigen receptor loci. Cell. 2010;141:419–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Subrahmanyam R, Chakroborty T, Sen R, Desiderio S. A plant homeodomain in RAG-2 that binds Hypermethylated lysine 4 of histone H3 is necessary for efficient antigen-receptor-gene rearrangement. Immunity. 2007;27:561–571. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews AG, et al. RAG2 PHD finger couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2007;450:1106–1110. doi: 10.1038/nature06431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baumann M, Mamais A, McBlane F, Xiao H, Boyes J. Regulation of V(D)J recombination by nucleosome positioning at recombination signal sequences. EMBO J. 2003;22:5197–5207. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golding A, Chandler S, Ballestar E, Wolffe AP, Schlissel MS. Nucleosome structure completely inhibits in vitro cleavage by the V(D)J recombinase. EMBO J. 1999;18:3712–3723. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon J, Imbalzano AN, Matthews A, Oettinger MA. Accessibility of nucleosomal DNA to V(D)J cleavage is modulated by RSS positioning and HMG1. Mol Cell. 1998;2:829–839. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du H, Ishii H, Pazin MJ, Sen R. Activation of 12/23-RSS-dependent RAG cleavage by hSWI/SNF complex in the absence of transcription. Mol Cell. 2008;31:641–649. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patenge N, Elkin SK, Oettinger MA. ATP-dependent remodeling by SWI/SNF and ISWI proteins stimulates V(D)J cleavage of 5 S arrays. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35360–35367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405790200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teng G, et al. RAG represents a widespread threat to the lymphocyte genome. Cell. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.009. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahman NS, Godderz LJ, Stray SJ, Capra JD, Rodgers KK. DNA cleavage of a cryptic recombination signal sequence by RAG1 and RAG2. Implications for partial V(H) gene replacement. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12370–12380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507906200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang M, Swanson PC. V(D)J recombinase binding and cleavage of cryptic recombination signal sequences identified from lymphoid malignancies. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6717–6727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710301200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis SM, Agard E, Suh S, Czyzyk L. Cryptic signals and the fidelity of V(D)J joining. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3125–3136. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Filippakopoulos P, et al. Histone recognition and large-scale structural analysis of the human bromodomain family. Cell. 2012;149:214–231. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang H, Rambaldi I, Daniels E, Featherstone M. Expression of the Wdr9 gene and protein products during mouse development. Dev Dyn. 2003;227:608–614. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phillips DL, et al. The dual bromodomain and WD repeat-containing mouse protein BRWD1 is required for normal spermiogenesis and the oocyte-embryo transition. Dev Biol. 2008;317:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper AB, et al. A unique function for cyclin D3 in early B cell development. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:489–497. doi: 10.1038/ni1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunn KL, Davie JR. Stimulation of the Ras-MAPK pathway leads to independent phosphorylation of histone H3 on serine 10 and 28. Oncogene. 2005;24:3492–3502. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhong SP, Ma WY, Dong Z. ERKs and p38 kinases mediate ultraviolet B-induced phosphorylation of histone H3 at serine 10. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20980–20984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909934199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Revilla-I-Domingo R, et al. The B-cell identity factor Pax5 regulates distinct transcriptional programmes in early and late B lymphopoiesis. EMBO J. 2012;31:3130–3146. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samstein RM, et al. Foxp3 exploits a pre-existent enhancer landscape for regulatory T cell lineage specification. Cell. 2012;151:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shogren-Knaak M, et al. Histone H4-K16 acetylation controls chromatin structure and protein interactions. Science. 2006;311:844–847. doi: 10.1126/science.1124000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen J, et al. B cell development in mice that lack one or both immunoglobulin kappa light chain genes. EMBO J. 1993;12:821–830. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farkas G, et al. The Trithorax-like gene encodes the Drosophila GAGA factor. Nature. 1994;371:806–808. doi: 10.1038/371806a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clapier CR, Cairns BR. The biology of chromatin remodeling complexes. Ann Rev Biochem. 2009;78:273–304. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.062706.153223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1213–1218. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stadhouders R, et al. Pre-B cell receptor signaling induces immunoglobulin kappa locus accessibility by functional redistribution of enhancer-mediated chromatin interactions. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Steensel B, Delrow J, Henikoff S. Chromatin profiling using targeted DNA adenine methyltransferase. Nat Genet. 2001;27:304–308. doi: 10.1038/85871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tee WW, Shen SS, Oksuz O, Narendra V, Reinberg D. Erk1/2 activity promotes chromatin features and RNAPII phosphorylation at developmental promoters in mouse ESCs. Cell. 2014;156:678–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zulio JM, et al. DNA sequence-dependent compartmentalization and silencing of chromatin at the nuclear lamina. Cell. 2012;149:1474–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yin FF, et al. Structure of the RAG1 nonamer binding domain with DNA reveals a dimer that mediates DNA synapsis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:499–508. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spanopoulou E, et al. The homeodomain region of Rag-1 reveals the parallel mechanisms of bacterial and V(D)J recombination. Cell. 1996;87:263–276. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang C, Pugh BF. Nucleosome positioning and gene regulation: advances through genomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:161–172. doi: 10.1038/nrg2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schlissel MS. Regulation of activation and recombination of the murine Igkappa locus. Immunol Rev. 2004;200:215–223. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morshead KB, Ciccone DN, Taverna SD, Allis CD, Oettinger MA. Antigen receptor loci poised for V(D)J rearrangement are broadly associated with BRG1 and flanked by peaks of histone H3 dimethylated at lysine 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11577–11582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932643100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osipovich O, et al. Essential function for SWI-SNF chromatin-remodeling complexes in the promoter-directed assembly of Tcrb genes. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:809–816. doi: 10.1038/ni1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bailey TL, Gribskov M. Combining evidence using p-values: application to sequence homology searches. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:48–54. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rashid NU, Giresi PG, Ibrahim JG, Sun W, Lieb JD. ZINBA integrates local covariates with DNA-seq data to identify broad and narrow regions of enrichment, even within amplified genomic regions. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R67. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-7-r67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen K, et al. DANPOS: dynamic analysis of nucleosome position and occupancy by sequencing. Genome Res. 2013;23:341–351. doi: 10.1101/gr.142067.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.