Abstract

18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid (18β-GA) has been proposed as a promising hepatoprotective agent. The current study aimed to investigate the protective action and the possible mechanisms of 18β-GA against cyclophosphamide (CP)-induced liver injury in rats, focusing on the role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) and NF-E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2). Rats were administered 18β-GA at doses 25 and 50 mg/kg 2 weeks prior to CP injection. Five days after CP administration, animals were sacrificed and samples were collected. CP induced hepatic damage evidenced by the histopathological changes and significant increase in serum pro-inflammatory cytokines, liver marker enzymes, and liver lipid peroxidation and nitric oxide (NO) levels. 18β-GA counteracted CP-induced oxidative stress and inflammation as assessed by restoration of the antioxidant defenses and diminishing of pro-inflammatory cytokines, lipid peroxidation, and NO production. These hepatoprotective effects appear to depend on activation of Nrf2 and PPARγ, and subsequent suppression of nuclear factor-kappa B. In conclusion, the present study provides evidence that 18β-GA exerts hepatoprotective effects against CP through induction of antioxidant defenses and suppression of inflammatory response. This report also confers new information that 18β-GA protects liver against the toxic effect of chemotherapeutic alkylating agents via activation of Nrf2 and PPARγ.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Hepatotoxicity, Inflammation, PPARs, Nrf2

Introduction

Hepatotoxicity represents the most important cause of the non-approval and withdrawal of drugs by the Food and Drug Administration (Mahmoud 2014). Cyclophosphamide (CP) is an alkylating agent used for treating a variety of cancers and as an immunosuppressive agent for organ transplantation (Shanafelt et al. 2007; Uber et al. 2007). The therapeutic uses of CP are often restricted due to its toxicity and wide adverse side effects (Papaldo et al. 2005). As a metabolically active organ, liver is particularly susceptible to reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced as by-products of normal metabolism and detoxification processes (Klaassen et al. 2008). CP-induced ROS generation and oxidative stress have been implicated in its hepatotoxic effects (Motawi et al. 2010). In addition, the cytochrome p450-mediated biotransformation of CP leads to formation of phosphoramide mustard and acrolein which are highly toxic (Kern and Kehrer 2002) and have the potential to generate superfluous ROS (Ahmadi et al. 2008).

Elevated ROS and electrophiles activate the antioxidant response element (ARE) leading to induction of antioxidant genes to protect cells against oxidative stress (Mathers et al. 2004). ARE-driven antioxidant gene expression is primarily regulated by NF-E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2; Copple et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2010). Nrf2 is a member of the cap ‘n’ collar family of basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors (Kobayashi and Yamamoto 2005). Nrf2 plays complex and multicellular roles in hepatic fibrosis, inflammation, hepatocarcinogenesis, and regeneration via its target gene induction (Shin et al. 2013). Upon cell stimulation, activated Nrf2 is translocated into the nucleus where it binds to the ARE and leads to expression of target genes (Farombi et al. 2008; Hong et al. 2010). Therefore, Nrf2 plays a role as multiorgan protector against oxidative stress through target gene induction (Lee et al. 2005).

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are proteins that belong to the nuclear receptor family of ligand-activated transcription factors. Upon ligand binding, they form heterodimers with retinoid X receptor (RXR) and result in modulation of gene transcription (Barish et al. 2006). There are three major isoforms of PPARs, including PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ (Michalik and Wahli 2008). In the liver, PPARs regulate inflammatory responses, cholesterol and bile acid homeostasis, carbohydrate/lipid metabolism, regenerative mechanisms, and cell differentiation/proliferation (Peyrou et al. 2012). Dysregulations of specific PPAR isoforms contribute to the development of a wide range of hepatic diseases (Peyrou et al. 2012). Also, several studies reported that PPARγ deficiency in hepatic stellate cells is associated with excessive formation of fibrotic tissue in the liver (Zhang et al. 2012) and activation of PPARγ signaling protects the liver against fibrosis (Nan et al. 2009) and drug-induced inflammation (Mahmoud 2014; Mahmoud et al. 2014). Thus, modulation of PPARγ might represent an important strategy for the treatment of liver diseases.

Glycyrrhiza glabra L. (Liquorice) root and its ingredients are widely used as a conditioning and flavoring agent and in herbal medicines for the treatment of various inflammatory diseases (Eisenbrand 2006). The major active ingredients of liquorice root are glycyrrhizin (GL), 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (18β-GA), and 18α-GA (Montoro et al. 2011). Studies have demonstrated several pharmacological effects of 18β-GA including anti-inflammatory, anti-ulcer, anti-viral, antioxidant, and hepatoprotective properties (Pezzuto 1997; Maitraie et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2011). Recently, 18β-GA was reported to attenuate 2-acetylaminofluorene-induced hepatotoxicity in Wistar rats (Hasan et al. 2015). Also, Chen et al. (2013) stated that upregulation of Nrf2 by glycyrrhetinic acid protected mice against carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced chronic liver fibrosis. However, the issues of an involvement of PPARγ and Nrf2 activation in the protective effects of 18β-GA against CP-induced hepatotoxicity have not been previously investigated. In this study, we have investigated whether 18β-GA, an active ingredient of G. glabra, might upregulate PPARγ and Nrf2, leading to protection against CP-induced hepatotoxicity in rats.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Cyclophosphamide (Endoxan) was supplied as vials from Baxter Oncology (Dusseldorf, Germany). 18β-GA, reduced glutathione (GSH), thiobarbituric acid (TBA), 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), pyrogallol, Tween 20, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were purchased from Sigma (USA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade and obtained from standard commercial supplies.

Animals and experimental design

Male Wistar rats weighing 130–150 g, obtained from the animal house of the National Research Centre (El-Giza, Egypt) were included in the present investigation. The animals were housed in plastic well-aerated cages (4 rats/cage) at normal atmospheric temperature (25 ± 2 °C) and normal 12-h light/dark cycle. Rats had free access to water and were supplied daily with laboratory standard diet of known composition. All animal procedures were undertaken with the approval of Institutional Animal Ethics Committee of Beni-Suef University (Egypt).

Rats were kept under observation for 1 week before the onset of the experiment for acclimatization and to exclude any intercurrent infection. To study the protective effects of 18β-GA against CP-induced hepatotoxicity, twenty-four male Wistar rats were randomly allocated into four groups having six in each as follows:

Group 1 (control): received the vehicle 0.5 % carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) by oral gavage for 15 days and a single intraperitoneal (ip) injection of saline at day 16.

Group 2 (CP): received 0.5 % CMC by oral gavage for 15 days and a single ip dose of 150 mg/kg CP at day 16.

Group 3 (CP + 25 mg GA): received 25 mg/kg GA suspended in 0.5 % CMC by oral gavage for 15 days and a single ip dose of 150 mg/kg CP at day 16.

Group 4 (CP + 50 mg GA): received 50 mg/kg GA suspended in 0.5 % CMC by oral gavage for 15 days and a single ip dose of 150 mg/kg CP at day 16.

The doses of 18β-GA were balanced consistently as indicated by any change in body weight to keep up comparable dosage for every kg body weight over the entire period of study.

Samples preparation

At the end of the experiment (5 days after CP administration), animals were sacrificed under ether anesthesia and blood samples were collected, left to coagulate, and centrifuged at 1000×g for 15 min to separate serum. Sera were then collected and kept at −20 °C as aliquots for subsequent biochemical assays. Liver samples were immediately excised and perfused with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Frozen samples (10 % w/v) were homogenized in chilled PBS, and the homogenates were centrifuged at 1500×g for 10 min. The clear homogenates were collected and used for subsequent assays. Samples from the liver were taken at the same time on RIPA buffer supplemented with proteinase inhibitors for western blotting analysis. Other liver samples were immediately excised, perfused with ice-cold PBS, and fixed in 10 % formalin for histological processing or kept frozen at −80 °C for gene expression analysis.

Biochemical assays

Assay of liver function markers

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) activities were determined according to the method of Schumann and Klauke (2003) using reagent kit purchased from Biosystems (Spain). Serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activities were measured using Spinreact (Spain) reagent kit according to the method of Wenger et al. (1984) and Teitz (1986), respectively. Serum gamma-glutamyl transferase (γGT) assay was performed according to Persijn and van der Slik (1976) using kits from Reactivos GPL (Spain). Concentration of albumin in serum was assayed following the methods of Webster (1974) using regent kits supplied by Spinreact (Spain).

Assay of serum cytokines

Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and IL-1β were determined using specific ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentrations of assayed cytokines were measured spectrophotometrically at 450 nm. Standard curves were constructed by using standard cytokines, and concentrations of the unknown samples were determined from the standard plots.

Assay of oxidative stress and antioxidant defense system

Lipid peroxidation content was assayed in liver homogenates by measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA) formation according to the method of Preuss et al. (1998). Nitric oxide (NO) was determined according to the method of Montgomery and Dymock (1961) using reagent kit purchased from Biodiagnostics (Egypt). Reduced glutathione (GSH) content and activities of the antioxidant enzymes, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT) were measured according to the methods of Beutler et al. (1963), Matkovics et al. (1998), Marklund and Marklund (1974), and Cohen et al. (1970), respectively.

Histopathological study

The liver samples were flushed with PBS and then fixed in 10 % buffered formalin for 24 h. After fixation, the specimens were dehydrated in ascending series of ethanol, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin wax. Blocks were made, and 4-μm-thick sections were cut by a sledge microtome. The paraffin-embedded liver sections were deparaffinized, washed with PBS, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The stained slides were examined under light microscope.

RNA isolation and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Gene expression analysis was performed as we previously described (Mahmoud 2014). In brief, total RNA was isolated from frozen liver samples using Fermentas RNA isolation kit and concentrations were quantified at 260 nm. RNA samples with A260/A280 ratios ≥1.7 were selected. Reverse transcription of RNA to cDNA was performed with 1 µg RNA using reverse transcription kit (Fermentas). Synthesized cDNA was amplified by SYBR Green master mix (Fermentas) in a total volume of 20 µL using the primer set described in Table 1. Reactions were seeded in a 96-well plate, and the PCR cycles included initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min and 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at Tm-5 for 60 s and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. The obtained amplification data were analyzed by the 2−∆∆Ct method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001), and the values were normalized to GAPDH.

Table 1.

Primer pairs used for qPCR

| Gene | GenBank accession number | Sequence 5′–3′ |

|---|---|---|

| SOD3 | NM_012880.1 | F: ACACCTATGCACTCCACAGAC R: ACATTCGACCTCTGGGGGTA |

| GPX2 | NM_183403.2 | F: GCATGGCTTACATCGCCAAG R: AGTCCCGGGTAGTTGTTCCT |

| CAT | M25670.1 | F: GCGGGAACCCAATAGGAGAT R: CAGGTTAGGTGTGAGGGACA |

| PPARγ | NM_001145367.1 | F: GGACGCTGAAGAAGAGACCTG R: CCGGGTCCTGTCTGAGTATG |

| Nrf2 | NM_031789.2 | F: TTGTAGATGACCATGAGTCGC R: TGTCCTGCTGTATGCTGCTT |

| iNOS | U03699.1 | F: ATTCCCAGCCCAACAACACA R: GCAGCTTGTCCAGGGATTCT |

| NF-κB | AF079314.1 | F: TCTCAGCTGCGACCCCG R: TGGGCTGCTCAATGATCTCC |

| β-Actin | NM_031144.3 | F: TACAACCTTCTTGCAGCTCCT R: CCTTCTGACCCATACCCACC |

Western blotting analysis

Western blotting for liver Nrf2, PPARγ, NF-κB, and iNOS was performed by using the standard method. Equal amounts of proteins were separated by 10 % SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electro-transferred to PVDF membrane. The membranes were blocked in 5 % w/v skimmed milk powder in Tris-buffered saline (TBS)/Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated with rabbit primary antibodies for Nrf2, PPARγ, NF-κB p65, iNOS, and GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. After washing with TBST, the membranes were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature and then washed and developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Scientific). The band intensity was quantified using ImageJ, normalized to GAPDH, and presented as % of control.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA), and all statistical comparisons were made by means of the one-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis. Results were articulated as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and a P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Effect of 18β-GA on liver function markers

The effects of CP-induced hepatotoxicity and the preventive effects of 18β-GA on serum markers of liver function are shown in Table 2. Serum activity of the liver function marker enzymes (AST, ALT, ALP, LDH, and γGT) was significantly (P < 0.001) increased in CP-administered rats in comparison with the control rats. Conversely, serum levels of albumin were significantly decreased in CP-administered rats compared with control rats. Oral administration of 18β-GA to CP-intoxicated rats significantly ameliorated the altered liver markers in a dose-dependent manner. The 25-mg dose of 18β-GA significantly ameliorated serum activities of all assayed enzymes, while its effect on serum albumin levels was nonsignificant (P > 0.05) compared to the CP-administered rats. On the other hand, the 50-mg dose of 18β-GA significantly ameliorated serum ALT, AST, LDH, and albumin when compared with the lower dose.

Table 2.

Serum markers of liver function in control, CP, and CP rats pretreated with 18β-GA

| Parameter | Control | CP | CP + 25 mg GA | CP + 50 mg GA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT (U/L) | 23.58 ± 4.51 | 85.44 ± 9.77*** | 49.22 ± 5.78### | 33.26 ± 5.02###$$ |

| AST (U/L) | 39.48 ± 8.03 | 106.51 ± 10.72*** | 65.18 ± 11.31### | 45.31 ± 8.69###$ |

| ALP (U/L) | 60.11 ± 6.29 | 149.43 ± 13.42*** | 81.55 ± 10.58### | 72.19 ± 15.70### |

| γGT (U/L) | 11.68 ± 4.07 | 31.42 ± 5.16*** | 17.44 ± 3.89## | 14.73 ± 4.26### |

| LDH (U/L) | 241.19 ± 18.81 | 467.22 ± 29.71*** | 317.55 ± 18.93### | 246.02 ± 21.82###$$ |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.09 ± 0.63 | 1.97 ± 0.31* | 2.80 ± 0.42 | 3.11 ± 0.53# |

Data are M ± SD (N = 6)

ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALP alkaline phosphatase, γGT gamma-glutamyl transferase, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, CP cyclophosphamide, GA glycyrrhetinic acid, SD standard deviation, vs versus

* P < 0.05 and *** P < 0.001 versus control, # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, and ### P < 0.001 versus CP, and $$ P < 0.01 versus CP + 25 mg GA group

Effect of 18β-GA on serum cytokines

Serum levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were significantly (P < 0.001) elevated in CP-administered rats when compared with the control group (Table 3). Both the 25- and 50-mg doses of 18β-GA significantly (P < 0.001) decreased the elevated cytokines level when supplemented prior to CP administration. The 50-mg dose of 18β-GA seemed to be more effective (P < 0.05) in reducing TNF-α when compared with the lower dose.

Table 3.

Serum levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in control, CP, and CP rats pretreated with 18β-GA

| Parameter | Control | CP | CP + 25 mg GA | CP + 50 mg GA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 34.17 ± 5.02 | 124.33 ± 14.32*** | 62.08 ± 8.79### | 40.19 ± 3.99###$ |

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | 26.75 ± 4.36 | 89.43 ± 13.76*** | 39.34 ± 7.76### | 32.11 ± 6.27### |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 39.29 ± 6.58 | 93.69 ± 7.81*** | 65.92 ± 8.94### | 47.01 ± 7.07### |

Data are M ± SD (N = 6)

TNF-α tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL interleukin, CP cyclophosphamide, GA glycyrrhetinic acid, SD standard deviation, vs versus

*** P < 0.001 versus control, ### P < 0.001 versus CP, and $ P < 0.05 versus CP + 25 mg GA group

Histopathological changes

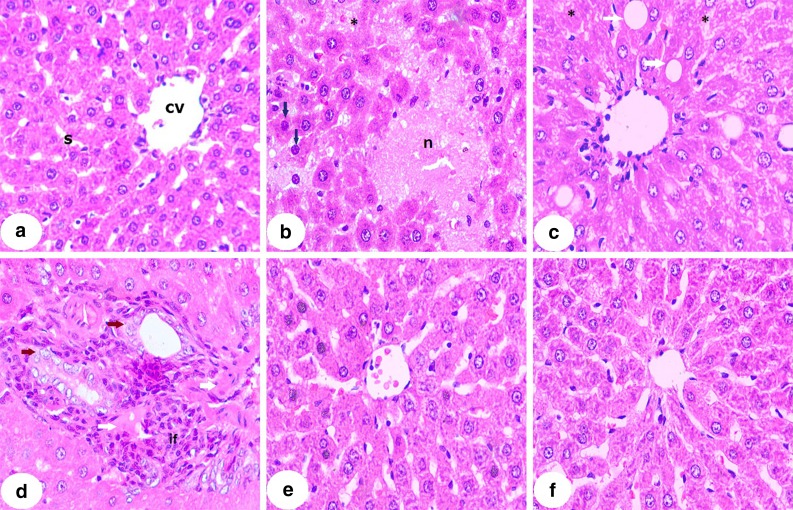

Microscopic investigation of H&E-stained liver section from control rats demonstrated normal hepatic strands, hepatocytes, and sinusoids (Fig. 1a). Liver sections from CP-induced rats showed hepatocellular focal degeneration and necrosis, hyperchromatic nuclei, hepatic cell karyolysis (Fig. 1b), fatty degeneration, cytoplasmic vacuolations, hydropic degeneration of hepatocytes (Fig. 1c), leukocytes infiltration and hyperproliferation around the deformed bile ducts, dysplasia, karyomegaly, nuclear atypia, and some fibrotic changes (Fig. 1d). On the contrary, 18β-GA-pretreated rats exhibited marked alleviation of the liver architecture with mild hepatocyte degenerations (Fig. 1e, f).

Fig. 1.

Photomicrographs of H&E-stained liver sections of control, CP, and CP rats pretreated with 18β-GA. a Liver section of control rat showing normal histological structure, b–d liver sections of CP-induced rats showing hepatocellular focal degeneration and necrosis (n), hyperchromatic nuclei (blue arrows), hepatic cell karyolysis (asterisk), fatty degeneration (white arrow), cytoplasmic vacuolations (v), hydropic degeneration of hepatocytes, leukocytes infiltration, and hyperproliferation around the deformed bile ducts, dysplasia, karyomegaly, nuclear atypia (brown arrows), and some fibrotic changes, e liver section of rats pretreated with 25 mg 18-β GA showing normal hepatocytes and mild central vain and sinusoid congestion, and f liver section of rats pretreated with 50 mg 18-β GA showing normal hepatocytes with mild degeneration (×400)

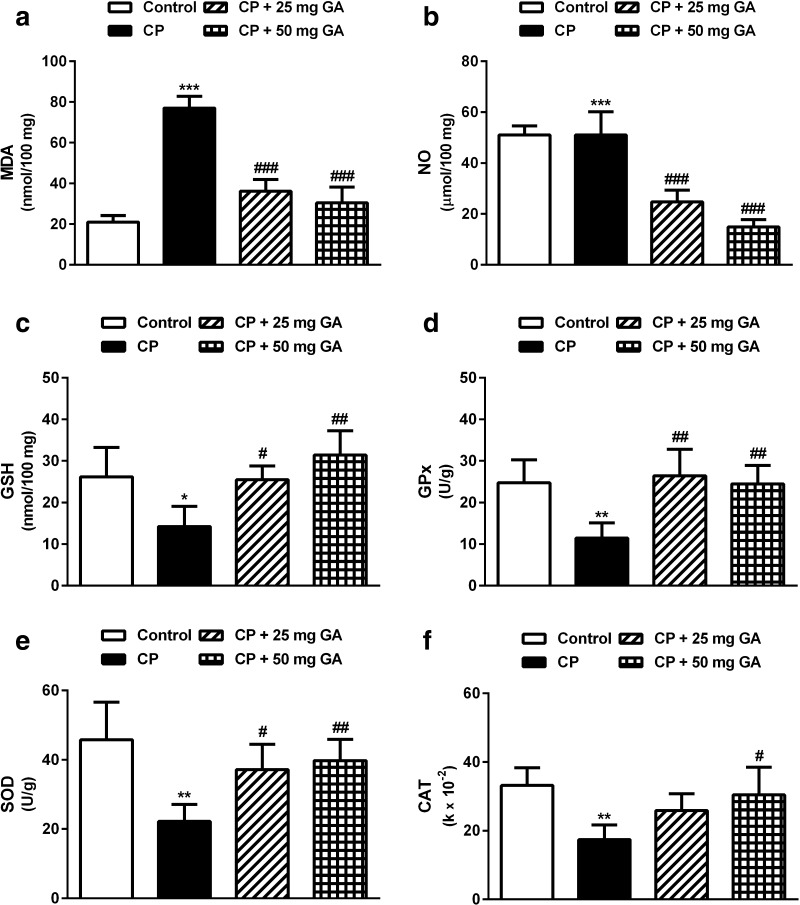

Effect of 18β-GA on hepatic oxidative stress and antioxidant markers

CP administration produced a significant (P < 0.001) increase in hepatic levels of the lipid peroxidation marker MDA and NO when compared with the corresponding control rats as depicted in Fig. 2a, b, respectively. Supplementation of CP-administered rats with either dose of 18β-GA potentially (P < 0.001) ameliorated the altered levels of MDA and NO. Although nonsignificant, the higher dose of 18β-GA was more effective in decreasing MDA and NO levels in the liver of CP-intoxicated rats when compared with the lower supplemented dose.

Fig. 2.

Effect of 18β-GA on liver oxidative stress and antioxidant defense system parameters. Data are M ± SD (N = 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 versus control, and # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, and ### P < 0.001 versus CP group. MDA malondialdehyde, NO nitric oxide, GSH glutathione, GPx glutathione peroxidase, SOD superoxide dismutase, CAT catalase, CP cyclophosphamide, GA glycyrrhetinic acid, SD standard deviation, vs versus

Conversely, GSH levels in the liver of CP-administered rats showed a significant (P < 0.05) decrease when compared with the control group (Fig. 2c). Oral supplementation of 25 mg 18β-GA significantly (P < 0.05) prevented the decline in GSH levels in liver tissue of the CP-administered rats. Administration of the higher 18β-GA dose produced a significant (P < 0.01) increase in hepatic GSH levels.

Similarly, activity of the antioxidant enzymes GPx, SOD, and CAT showed a significant (P < 0.01) decrease in liver of the CP-administered rats when compared with the control group (Fig. 2d–f). Oral supplementation of 25 mg 18β-GA increased the activity of GPx (P < 0.01) and SOD (P < 0.05); however, its effect on CAT activity was nonsignificant (P > 0.05) as compared with the CP-administered group. On the other hand, the 50-mg dose of 18β-GA significantly alleviated the activity of GPx (P < 0.01), SOD (P < 0.01), and CAT (P < 0.05) when compared with the CP control group of rats.

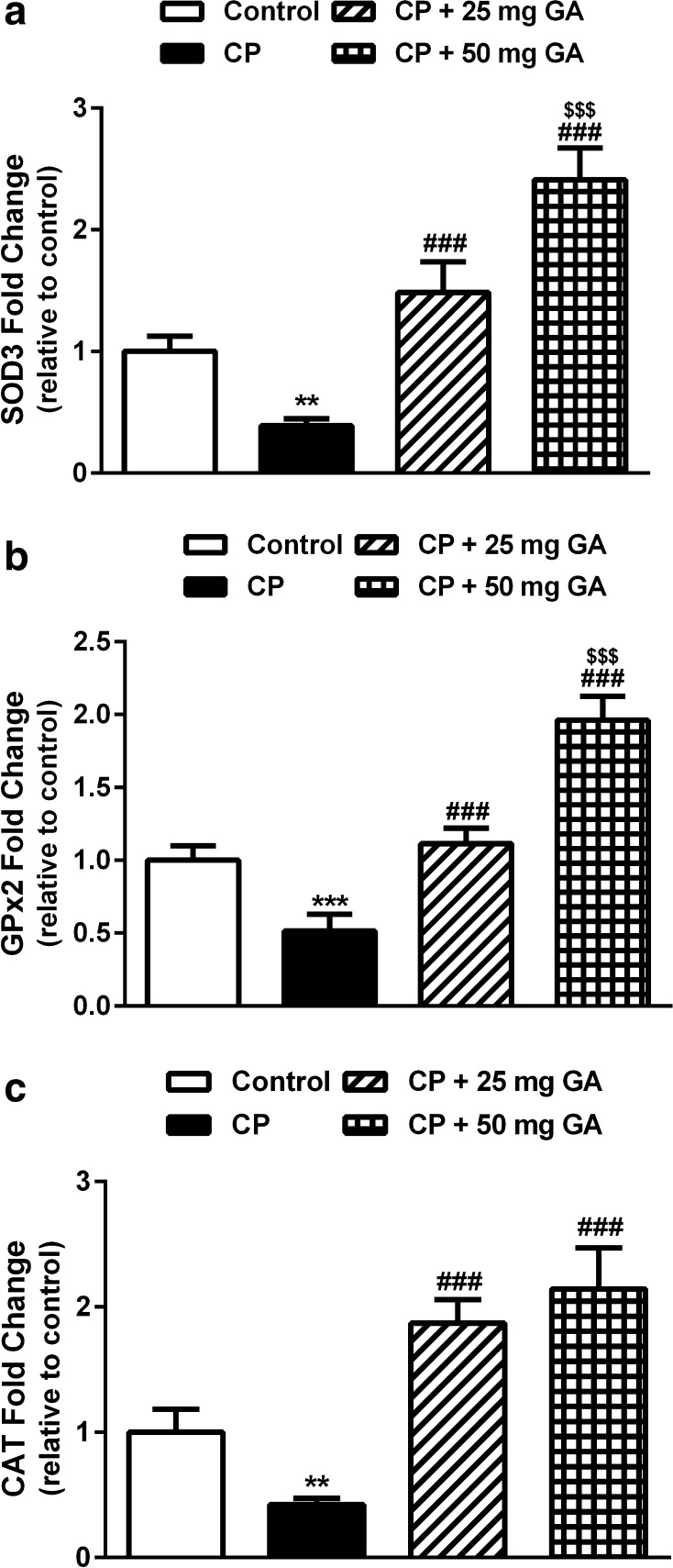

Effect of 18β-GA on SOD, GPx, and CAT gene expression

Gene expression analysis showed significant downregulation of hepatic SOD (P < 0.01), GPx (P < 0.001), and CAT (P < 0.01) in CP-intoxicated rats when compared with the corresponding controls (Fig. 3a–c). Pretreatment of the CP-induced rats with both doses of 18β-GA produced significant (P < 0.001) upregulation of the antioxidant enzymes mRNA. The 50 mg 18β-GA dosage seemed to be more effective in ameliorating the altered expression levels of SOD and GPx.

Fig. 3.

Liver SOD, GPx, and CAT mRNA expression in control, CP, and CP rats pretreated with 18β-GA. Data are M ± SD (N = 6). **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus control, ### P < 0.001 versus CP, and $$$ P < 0.001 versus CP + 25 mg GA group. SOD superoxide dismutase, GPx glutathione peroxidase, CAT catalase, CP cyclophosphamide, GA glycyrrhetinic acid, SD standard deviation, vs versus

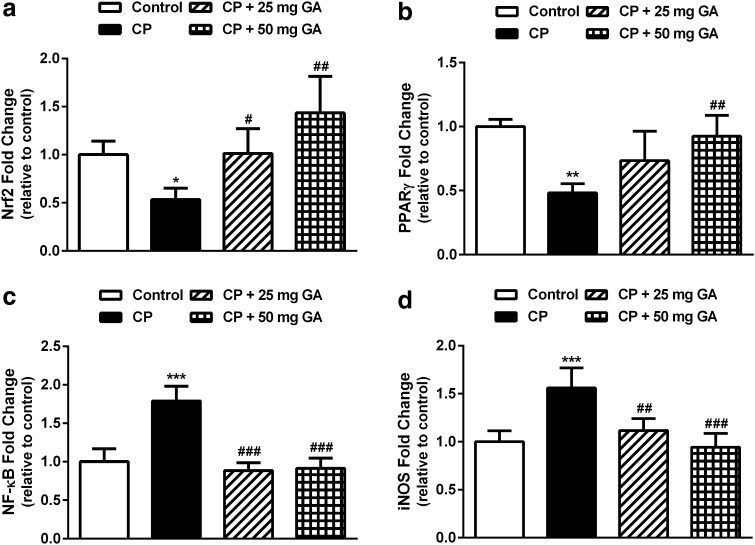

Effect of 18β-GA on Nrf2, PPARγ, NF-κB, and iNOS gene expression

qPCR analysis of gene expression showed a significant downregulation of both Nrf2 (P < 0.05) and PPARγ (P < 0.01) in the liver of CP-intoxicated rats when compared with the corresponding controls (Fig. 4a, b). Oral supplementation of 25 mg 18β-GA produced nonsignificant (P < 0.05) upregulation of PPARγ mRNA when compared with the CP-administered rats, while Nrf2 was significantly (P < 0.05) upregulated. The 50 mg 18β-GA dose was more effective where it produced significant (P < 0.01) upregulation of both Nrf2 and PPARγ in liver of CP-administered rats.

Fig. 4.

Liver Nrf2, PPARγ, NF-κB, and iNOS mRNA expression in control, CP, and CP rats pretreated with 18β-GA. Data are M ± SD (N = 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 versus control, and # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, and ### P < 0.001 versus CP group. Nrf2 NF-E2-related factor-2, PPARγ peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, NF-κB nuclear factor-kappa B, iNOS inducible nitric oxide synthase, CP cyclophosphamide, GA glycyrrhetinic acid, SD standard deviation, vs versus

On the other hand, CP-intoxicated rats exhibited significant (P < 0.001) upregulation of NF-κB and iNOS mRNA expression when compared with the control rats, as represented in Fig. 4c, d. Supplementation of either dose of 18β-GA potentially downregulated NF-κB and iNOS mRNA expression in liver of the CP-intoxicated rats.

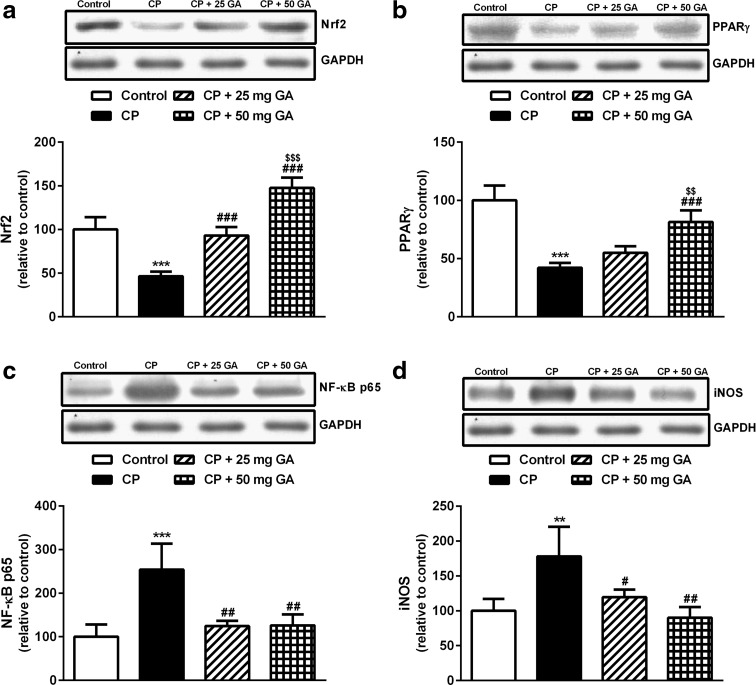

Effect of 18β-GA on Nrf2, PPARγ, NF-κB, and iNOS protein expression

CP-administered rats exhibited significant (P < 0.001) decrease in hepatic Nrf2 and PPARγ protein expression when compared with the corresponding control rats as shown by western blotting (Fig. 5a, b). While supplementation of CP-administered rats with the lower dose of 18β-GA produced a nonsignificant (P > 0.05) effect on hepatic PPARγ protein expression, it produced a significant (P < 0.001) increase in Nrf2 protein levels. On the other hand, oral supplementation of 50-mg dose of 18β-GA to CP-administered rats significantly (P < 0.001) increased the protein levels of both Nrf2 and PPARγ when compared with the CP control group. In addition, the higher 18β-GA dose significantly increased PPARγ (P < 0.01) and Nrf2 (P < 0.001) protein expression when compared with its lower dose.

Fig. 5.

Western blotting analysis of liver Nrf2, PPARγ, NF-κB, and iNOS protein expression in control, CP, and CP rats pretreated with 18β-GA. (Top) Gel photograph depicting representative proteins and (Bottom) corresponding densitometric analysis. Data are M ± SD (N = 6). **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus control, # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, and ### P < 0.001 versus CP, and $$$ P < 0.001 versus CP + 25 mg GA group. Nrf2 NF-E2-related factor-2, PPARγ peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, NF-κB nuclear factor-kappa B, iNOS inducible nitric oxide synthase, CP cyclophosphamide, GA glycyrrhetinic acid, SD standard deviation, vs versus

On the contrary, CP-intoxicated rats showed significant upregulation of NF-κB (P < 0.001) and iNOS (P < 0.01) protein expression when compared with the control rats, as represented in Fig. 5c, d. Pretreatment of the CP-induced rats with either dose of 18β-GA markedly downregulated NF-κB and iNOS expression. The higher 18β-GA produced a significant (P < 0.05) downregulation of iNOS when compared with the lower dose.

Discussion

The therapeutic uses of CP against various cancers are often restricted because of its toxicity and wide adverse side effects. CP-induced hepatotoxicity occurs at high chemotherapeutic dosage (de Jonge et al. 2006) and at lower doses attained during treating patients with autoimmune diseases (Akay et al. 2006; Martínez-Gabarrón et al. 2011). In the present study, CP-induced acute hepatotoxicity is evident by increased serum activities of ALT, AST, LDH, ALP, and γGT, along with the declined albumin levels. These findings are in consistent with our recent studies demonstrating increased liver marker enzymes in serum of CP-intoxicated rats (Mahmoud et al. 2013; Germoush and Mahmoud 2014; Mahmoud 2014). The elevated serum enzymes might be attributed to cell damage caused by CP-induced oxidative stress and inflammation (Dang et al. 2008). The assayed serum transaminases and other enzymes are sensitive markers of liver injury as they are found in the cytoplasm of liver cells and leak into blood circulation following cell damage (Ramaiah 2007). The induced hepatotoxicity due to CP administration was further confirmed by the histological alterations including fatty degeneration of hepatocytes, necrosis, karyolysis, inflammatory cell infiltrations, and other manifestations. Pretreatment of the CP-induced rats with either dose of 18β-GA significantly ameliorated serum levels of liver marker enzymes in a dose-dependent manner, proving the hepatoprotective and membrane stabilizing efficacies of 18β-GA. Accordingly, studies have demonstrated that 18β-GA decreased serum transaminases in 2-acetylaminofluorene-induced hepatotoxicity in rats (Hasan et al. 2015) and in CCl4-induced chronic liver fibrosis in mice (Chen et al. 2013).

The current findings showed that CP administration induced marked increase in the hepatic lipid peroxidation marker MDA. The studies of Fraiser et al. (1991) and Lameire et al. (2011) reported that CP produces highly reactive electrophiles with catastrophic effects on cell membranes. Also, CP-induced hepatotoxicity has been reported to involve lipid peroxidation due to excessive formation of ROS (Bhatia et al. 2008). Acrolein, a metabolite of CP, and MDA belong to the carbonyl compounds which can cause structural and functional changes in the enzymes (Tripathi and Jena 2009). CP-induced lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress has been previously reported in our studies (Mahmoud et al. 2013; Germoush and Mahmoud 2014; Mahmoud 2014). Interestingly, pretreatment with 18β-GA markedly protected rats against CP-induced lipid peroxidation, indicating its radical scavenging activity.

Similarly, CP-intoxicated rats exhibited significant increase in NO levels which could be explained by the induced upregulation of iNOS. The crucial role of NO in pathogenesis of the adverse effects of CP is quite well confirmed in several studies (Al-Yahya et al. 2009). In this context, we recently reported increased NO levels and upregulation of iNOS in liver of CP-induced rats (Mahmoud 2014). The produced NO could react with superoxide anions to produce the potent and versatile oxidant peroxynitrite (McKim et al. 2003), and stimulate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines through the activation of NF-κB in Kupffer cells (Matata and Galiñanes 2002). Supplementation of 18β-GA potentially decreased NO levels in the liver of CP-administered rats. These findings could be attributed to the ability of 18β-GA to downregulate iNOS expression.

The observed depletion of GSH in liver of CP-administered rats could be resulted by the direct conjugation of CP metabolites with GSH (Yousefipour et al. 2005). GSH plays a significant role against oxidative stress by neutralizing the hydroxyl radicals (Circu and Aw 2011) or as a substrate for GPx (Franco et al. 2007). GSH depletion leads to declined cellular defense against free radical-induced injury resulting in necrotic cell death (Srivastava and Shivanandappa 2010). Thus, prevention of GSH depletion could be a part of the hepatoprotective mechanism of 18β-GA. Accordingly, CP administration produced marked decrease in the hepatic activity as well as gene expression of SOD, CAT, and GPx. We have demonstrated decreased activity of the enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant defenses in the liver of CP-intoxicated rats which was associated with CP-induced oxidative stress (Mahmoud 2014). SOD, CAT, and GPx play a crucial role in protecting the body against the deleterious effects of ROS and free radicals (Wei et al. 2011). Therefore, 18β-GA seems to exert its protective effects against CP by enhancing the hepatic antioxidant defenses.

The increase in expression and activity of the antioxidant defense enzymes by 18β-GA in the current study could be directly linked to upregulation of the transcription factor Nrf2. Nrf2 is essential in tissue protection from oxidants through binding to cis-acting ARE and subsequent induction of antioxidant and defense gene expression (Kensler et al. 2007). Under normal physiological conditions, Nrf2 is located in the cytoplasm inactivated by forming a complex with its repressor Kelch-like ECH2-associated protein (Keap 1) (Kang et al. 2004). Upon stimulation, Nrf2 dissociates from Keap 1, translocates into the nucleus, binds to ARE, and induces expression of the antioxidant enzymes SOD, CAT, and GPx (Patel and Maru 2008; Bardag-Gorce et al. 2011). Therefore, upregulation of Nrf2 can result in a reduction in the level of reactive oxidants by increasing expression of the antioxidant defense enzymes and correspondingly, less cell injury. Our findings showed a dramatic downregulation of Nrf2 mRNA and protein expression in liver tissue of CP-administered rats which was reversed by 18β-GA pretreatment. The expression level of Nrf2 is strongly correlated with the expression levels of SOD, CAT, and GPx; however, the exact mechanism of 18β-GA-induced upregulation of Nrf2 needs further investigation.

During drug-induced toxicity, tissue damage leads to generation of inflammatory mediators by the immune cells as well as by injured cells (Akcay et al. 2009). Various inflammatory mediators produced during drug-induced hepatic injury have been reported to promote tissue damage (Ishida et al. 2002). The generated inflammatory mediators induce migration and infiltration of leukocytes into the site of injury and provoke the primary injury induced by the toxicant (Akcay et al. 2009). Also, hepatotoxicity-associated inflammatory cytokines were reported to mediate monocyte/Kupffer cell activation and increase vascular permeability and apoptosis of hepatocytes (Mohammed et al. 2004). In the present study, CP administration induced significant increase in serum levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. These findings are similar to those observed in our recent studies (Germoush and Mahmoud 2014; Mahmoud 2014) where we reported marked increase in circulatory levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in CP-treated rats. Through binding to their receptors, IL-1β and TNF-α elicit potent pro-inflammatory actions (Ishida et al. 2002) and activate the pro-apoptotic caspase cascade (Tacke et al. 2009), respectively. The elevated levels of circulatory inflammatory cytokines are in consistent with the recorded significant upregulation of NF-κB, induced by ROS, which is well known to regulate the expression of various genes including inflammatory cytokines and iNOS (Pikarsky et al. 2004). CP promoted upregulation of NF-κB and iNOS with subsequent production of NO, and pro-inflammatory cytokines reflect the degree of inflammation in the induced rats. Pretreatment of rats with both doses of 18β-GA potentially protected against CP-induced inflammation through downregulation of NF-κB and iNOS expression, and attenuation of pro-inflammatory cytokines production.

These interesting findings provide strong evidence on the anti-inflammatory efficacy of 18β-GA, which is one of the significant mechanisms for prevention of drug-induced hepatotoxicity. The anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective effects of 18β-GA may be explained, at least in part, via its ability to upregulate PPARγ expression in the liver. After interaction with ligands, PPARγ translocates into the nucleus and heterodimerizes with RXR. This complex binds to peroxisome proliferator response elements (PPREs), found in the promoters of PPAR responsive genes, and thereby controls their expression (Berger and Moller 2002). Activated PPARγ has been reported to decrease the activity of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STATs), NF-κB, and activator protein 1 (AP-1). This subsequently suppresses synthesis of iNOS (Pascual et al. 2005) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (De Bosscher et al. 2006). In this context, we recently reported that PPARγ activation protected against CP and isoniazid induced oxidative stress and inflammation in rats (Mahmoud 2014; Mahmoud et al. 2014). Also, studies have demonstrated that PPARγ activation reduces generation of ROS from leukocytes of obese subjects (Garg et al. 2000), decreases production of superoxide radicals from monocytes in diabetic patients (Marfella et al. 2006), and eliminates oxidative stress in rodents (Dobrian et al. 2004). Furthermore, PPARγ upregulated the expression of CAT (Okuno et al. 2008) and SOD (Gong et al. 2012) in rodents through binding to its elements in the promoters of their genes.

The hepatoprotective effects of 18β-GA in the present investigation could be attributed to co-activation and possible interaction between PPARγ and Nrf2. This interaction occurs through multiple mechanisms. First, ARE and PPRE coexist in the same genes such as CAT (Kwak et al. 2001; Girnun et al. 2002); second, a reciprocal transcriptional regulation exists between PPARγ and Nrf2 genes, PPARγ gene contains ARE (Cho et al. 2010), and conversely, Nrf2 gene appears to contain PPREs (Shih et al. 2005); third, the effect of Nrf2 in ameliorating oxidative stress was proposed to be through NF-κB inhibition (Bowie and O’Neill 2000). Hence, an interaction between Nrf2 and PPARγ may be through inhibition of NF-κB. However, a limitation of this study was to determine Nrf2 and PPARγ in nuclear extracts for achieving better results.

In conclusion, the present study confers new information on the protective mechanism of 18β-GA against CP-induced liver injury. 18β-GA has shown strong modulatory potential against CP-induced inflammation and oxidative stress via induction of antioxidant defenses and suppression of ROS production. These hepatoprotective effects appear to depend on the co-activation of Nrf2 and PPARγ, and subsequent suppression of NF-κB. It seems that the simultaneous activation of both PPARγ and Nrf2 may have a synergistic effect in protecting against CP-induced hepatotoxicity.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contribution

AMM designed and conceived the study, performed experiments (animal treatments, and biochemical, gene expression and histological analysis), analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript. HSA participated in western blotting. Both authors read and approved the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- 18β-GA

18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid

- CP

Cyclophosphamide

- PPARγ

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

- Nrf2

NF-E2-related factor-2

- NO

Nitric oxide

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor-kappa B

- iNOS

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- ARE

Antioxidant response element

- bZIP

Basic leucine zipper

- RXR

Retinoid X receptor

- GL

Glycyrrhizin

- CCl4

Carbon tetrachloride

- GSH

Reduced glutathione

- TBA

Thiobarbituric acid

- DTNB

5,5′-Dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid)

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- CMC

Carboxymethylcellulose

- ip

Intraperitoneal

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- ALP

Alkaline phosphatase

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- γGT

Gamma-glutamyl transferase

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- IL-6

Interleukin 6

- IL-1β

Interleukin 1beta

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- H&E

Hematoxylin and eosin

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- CAT

Catalase

- GPx

Glutathione peroxidase

- qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- SD

Standard deviation

- Keap 1

Kelch-like ECH2-associated protein

- PPREs

Peroxisome proliferator response elements

- STATs

Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- AP-1

Activator protein 1

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Ayman Mahmoud and Hussein Al-Dera declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed.

References

- Ahmadi A, Hosseinimehr S, Naghshvar F, Hajir E, Ghahremani M. Chemoprotective effects of hesperidin against genotoxicity induced by cyclophosphamide in mice bone marrow cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2008;31:794–797. doi: 10.1007/s12272-001-1228-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akay H, Akay T, Secilmis S, Kocak Z, Donderici O. Hepatotoxicity after low-dose cyclophosphamide therapy. South Med J. 2006;99:1399–1400. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000251467.62842.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akcay A, Nguyen Q, Edelstein CL. Mediators of inflammation in acute kidney injury. Mediators Inflamm. 2009;2009:137072. doi: 10.1155/2009/137072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Yahya AA, Al-Majed AA, Gado AM, Daba MH, Al-Shabanah OA, Abd-Allah AR. Acacia senegal gum exudate offers protection against cyclophosphamide-induced urinary bladder cytotoxicity. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2009;2:207–213. doi: 10.4161/oxim.2.4.8878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardag-Gorce F, Oliva J, Lin A, Li J, French BA, French SW. Proteasome inhibitor up regulates liver antioxidative enzymes in rat model of alcoholic liver disease. Exp Mol Pathol. 2011;90:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barish GD, Narkar VA, Evans RM. PPARδ: a dagger in the heart of the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Investig. 2006;116:590–597. doi: 10.1172/JCI27955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger J, Moller DE. The mechanisms of action of PPARs. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:409–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler E, Duron O, Kelly BM. Improved method for the determination of blood glutathione. J Lab Clin Med. 1963;61:882–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia K, Ahmad F, Rashid H, Raisuddin S. Protective effect of S-allylcysteine against cyclophosphamide-induced bladder hemorrhagic cystitis in mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:3368–3374. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie A, O’Neill LA. Oxidative stress and nuclear factor-kappa B activation: a reassessment of the evidence in the light of recent discoveries. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:13–23. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Zou L, Li L, Wu T, Uversky VN. The protective effect of glycyrrhetinic acid on carbon tetrachloride-induced chronic liver fibrosis in mice via upregulation of Nrf2. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e53662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HY, Gladwell W, Wang X, et al. Nrf2-regulated PPARγ expression is critical to protection against acute lung injury in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:170–182. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200907-1047OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Circu ML, Aw TY. Redox biology of the intestine. Free Radic Res. 2011;45:1245–1266. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2011.611509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G, Dembiec D, Marcus J. Measurement of catalase activity in tissue extracts. Anal Biochem. 1970;34:30–38. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copple IM, Goldring CE, Kitteringham NR, Park BK. The Keap1-Nrf2 cellular defense pathway: mechanisms of regulation and role in protection against drug-induced toxicity. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2010;196:233–266. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00663-0_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang K, Lamb K, Cohen M, Bielefeldt K, Gebhart GF. Cyclophosphamide-induced bladder inflammation sensitizes and enhances P2X receptor function in rat bladder sensory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:49–59. doi: 10.1152/jn.00211.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bosscher K, Vanden Berghe W, Haegeman G. Cross-talk between nuclear receptors and nuclear factor kappa B. Oncogene. 2006;25:6868–6886. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge ME, Huitema AD, Beijnen JH, Rodenhuis S. High exposures to bioactivated cyclophosphamide are related to the occurrence of veno-occlusive disease of the liver following high-dose chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1226–1230. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrian AD, Schriver SD, Khraibi AA, Prewitt RL. Pioglitazone prevents hypertension and reduces oxidative stress in diet-induced obesity. Hypertension. 2004;43:48–56. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000103629.01745.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbrand G. Glycyrrhizin. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2006;50:1087–1088. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farombi EO, Shrotriya S, Na H-K, Kim S-H, Surh Y-J. Curcumin attenuates dimethylnitrosamine-induced liver injury in rats through Nrf2-mediated induction of heme oxygenase-1. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:1279–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraiser LH, Kanekal S, Kehrer JP. Cyclophosphamide toxicity: characterising and avoiding the problem. Drugs. 1991;42:781–795. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199142050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco R, Schoneveld OJ, Pappa A, Panayiotidis MI. The central role of glutathione in the pathophysiology of human diseases. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2007;113:234–258. doi: 10.1080/13813450701661198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg R, Kumbkarni Y, Aljada A, et al. Troglitazone reduces reactive oxygen species generation by leukocytes and lipid peroxidation and improves flow-mediated vasodilatation in obese subjects. Hypertension. 2000;36:430–435. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.36.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germoush MO, Mahmoud AM. Berberine mitigates cyclophosphamide-induced hepatotoxicity by modulating antioxidant status and inflammatory cytokines. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:1103–1109. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1665-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girnun GD, Domann FE, Moore SA, Robbins ME. Identification of a functional peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor response element in the rat catalase promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:2793–2801. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong P, Xu H, Zhang J, Wang Z. PPAR expression and its association with SOD and NF-κB in rats with obstructive jaundice. Biomed Res India. 2012;23:551–560. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan S, Khan R, Ali N, et al. 18-β glycyrrhetinic acid alleviates 2-acetylaminofluorene-induced hepatotoxicity in Wistar rats: role in hyperproliferation, inflammation and oxidative stress. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2015;34:628–641. doi: 10.1177/0960327114554045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y, Yan W, Chen S, Cr Sun, Zhang JM. The role of Nrf2 signaling in the regulation of antioxidants and detoxifying enzymes after traumatic brain injury in rats and mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2010;31(11):1421–1430. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida Y, Kondo T, Ohshima T, Fujiwara H, Iwakura Y, Mukaida N. A pivotal involvement of IFN-γ in the pathogenesis of acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury. FASEB J. 2002;16:1227–1236. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0046com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MI, Kobayashi A, Wakabayashi N, Kim SG, Yamamoto M. Scaffolding of Keap1 to the actin cytoskeleton controls the function of Nrf2 as key regulator of cytoprotective phase 2 genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2046–2051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308347100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensler TW, Wakabayashi N, Biswal S. Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu Rev Pharmacol. 2007;47:89–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern JC, Kehrer JP. Acrolein-induced cell death: a caspase-influenced decision between apoptosis and oncosis/necrosis. Chem Biol Interact. 2002;139:79–95. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2797(01)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen CD, Casarett LJ, Doull J. Casarett and Doull’s toxicology: the basic science of poisons. 7. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Yamamoto M. Molecular mechanisms activating the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway of antioxidant gene regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:385–394. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak MK, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Sutter TR, Kensler TW. Role of transcription factor Nrf2 in the induction of hepatic phase 2 and antioxidative enzymes in vivo by the cancer chemoprotective agent, 3H-1, 2-dimethiole-3-thione. Mol Med. 2001;7:135–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lameire N, Kruse V, Rottey S. Nephrotoxicity of anticancer drugs—an underestimated problem? Acta Clin Belg. 2011;66:337–345. doi: 10.1179/ACB.2011.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JM, Li J, Johnson DA, Stein TD, Kraft AD, Calkins MJ, Jakel RJ, Johnson JA. Nrf2, a multi-organ protector? FASEB J. 2005;19:1061–1066. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2591hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud AM. Hesperidin protects against cyclophosphamide-induced hepatotoxicity by upregulation of PPARγ and abrogation of oxidative stress and inflammation. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;92:717–724. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2014-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud AM, Hussein OE, Ramadan SA. Amelioration of cyclophosphamide-induced hepatotoxicity by the brown seaweed Turbinaria ornata. Int J Clin Toxicol. 2013;1:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud AM, Germoush MO, Soliman AS. Berberine attenuates isoniazid-induced hepatotoxicity by modulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, oxidative stress and inflammation. Int J Pharmacol. 2014;10:451–460. doi: 10.3923/ijp.2014.451.460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maitraie D, Hung CF, Tu HY, et al. Synthesis, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activities of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid derivatives as chemical mediators and xanthine oxidase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:2785–2792. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marfella R, D’Amico M, Esposito K, et al. The ubiquitin-proteasome system and inflammatory activity in diabetic atherosclerotic plaques: effects of rosiglitazone treatment. Diabetes. 2006;55:622–632. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.03.06.db05-0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marklund S, Marklund G. Involvement of the superoxide anion radical in the autoxidation of pyrogallol and a convenient assay for superoxide dismutase. Eur J Biochem. 1974;47:469–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Gabarrón M, Enríquez R, Sirvent AE, García-Sepulcre M, Millán I, Amorós F. Hepatotoxicity following cyclophosphamide treatment in a patient with MPO-ANCA vasculitis. Nefrologia. 2011;31:496–498. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2011.May.10917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matata BM, Galiñanes M. Peroxynitrite is an essential component of cytokines production mechanism in human monocytes through modulation of nuclear factor-kappa B DNA binding activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2330–2335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers J, Fraser JA, McMahon M, Saunders RD, Hayes JD, McLellan LI. Antioxidant and cytoprotective responses to redox stress. Biochem Soc Symp. 2004;71:157–176. doi: 10.1042/bss0710157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matkovics B, Szabo L, Varga IS. Determination of enzyme activities in lipid peroxidation and glutathione pathways (in Hungarian) Lab Diagn. 1998;15:248–249. [Google Scholar]

- McKim SE, Gäbele E, Isayama F, et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase is required in alcohol-induced liver injury: studies with knockout mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1834–1844. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalik L, Wahli W. PPARs mediate lipid signaling in inflammation and cancer. PPAR Res. 2008;2008:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2008/134059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed NA, Abd El-Aleem SA, El-Hafiz HA, McMahon RF. Distribution of constitutive (COX-1) and inducible (COX-2) cyclooxygenase in postviral human liver cirrhosis: a possible role for COX-2 in the pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:350–354. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.012120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery HAC, Dymock JF. The determination of nitrite in water. Analyst. 1961;86:414–416. [Google Scholar]

- Montoro P, Maldini M, Russo M, Postorino S, Piacente S, Pizza C. Metabolic profiling of roots of liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) from different geographical areas by ESI/MS/MS and determination of major metabolites by LC-ESI/MS and LC-ESI/MS/MS. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2011;54:535–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motawi TMK, Sadik NAH, Refaat A. Cytoprotective effects of DL-alpha-lipoic acid or squalene on cyclophosphamide-induced oxidative injury: an experimental study on rat myocardium, testicles and urinary bladder. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:2326–2336. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.05.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan YM, Fu N, Wu WJ, et al. Rosiglitazone prevents nutritional fibrosis and steatohepatitis in mice. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:358–365. doi: 10.1080/00365520802530861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno Y, Matsuda M, Kobayashi H, et al. Adipose expression of catalase is regulated via a novel remote PPARγ-responsive region. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366:698–704. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaldo P, Lopez M, Marolla P, et al. Impact of five prophylactic filgrastim schedules on hematologic toxicity in early breast cancer patients treated with epirubicin and cyclophosphamide. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6908–6918. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual G, Fong AL, Ogawa S, et al. A SUMOylation-dependent pathway mediates transrepression of inflammatory response genes by PPAR-γ. Nature. 2005;437:759–763. doi: 10.1038/nature03988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R, Maru G. Polymeric black tea polyphenols induce phase II enzymes via Nrf2 in mouse liver and lungs. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:1897–1911. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persijn JP, van der Slik W. A new method for the determination of γ-glutamyltransferase in serum. Z Klin Chem Klin Biochem. 1976;14:421–427. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1976.14.1-12.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyrou M, Ramadori P, Bourgoin L, Foti M. PPARs in liver diseases and cancer: epigenetic regulation by microRNAs. PPAR Res. 2012;2012:757803. doi: 10.1155/2012/757803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezzuto JM. Plant-derived anticancer agents. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;53:121–133. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(96)00654-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikarsky E, Porat RM, Stein I, et al. NF-κB functions as a tumour promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature. 2004;431:461–466. doi: 10.1038/nature02924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss HG, Jarrell ST, Scheckenbach R, Lieberman S, Anderson RA. Comparative effects of chromium, vanadium and gymnema sylvestre on sugar-induced blood pressure elevations in SHR. J Am Coll Nutr. 1998;17:116–123. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1998.10718736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaiah SK. A toxicologist guide to the diagnostic interpretation of hepatic biochemical parameters. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:1551–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann G, Klauke R. New IFCC reference procedures for the determination of catalytic activity concentrations of five enzymes in serum: preliminary upper reference limits obtained in hospitalized subjects. Clin Chim Acta. 2003;327:69–79. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(02)00341-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt TD, Lin T, Geyer SM, et al. Pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab regimen in older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. CNCR Cancer. 2007;109:2291–2298. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih AY, Imbeault S, Barakauskas V, et al. Induction of the Nrf2-driven antioxidant response confers neuroprotection during mitochondrial stress in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22925–22936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414635200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SM, Yang JH, Ki SH. Role of the Nrf2-ARE pathway in liver diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:763257. doi: 10.1155/2013/763257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A, Shivanandappa T. Hepatoprotective effect of the root extract of Decalepis hamiltonii against carbon tetrachloride-induced oxidative stress in rats. Food Chem. 2010;118:411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tacke F, Luedde T, Trautwein C. Inflammatory pathways in liver homeostasis and liver injury. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2009;36:4–12. doi: 10.1007/s12016-008-8091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitz N. Fundamentals of clinical chemistry. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co.; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi DN, Jena GB. Intervention of astaxanthin against cyclophosphamide-induced oxidative stress and DNA damage: a study in mice. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;180:398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uber WE, Self SE, Van Bakel AB, Pereira NL. Acute antibody-mediated rejection following heart transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2064–2074. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YP, Cheng ML, Zhang BF, Mu M, Wu J. Effects of blueberry on hepatic fibrosis and transcription factor Nrf2 in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2657–2663. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i21.2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CY, Kao TC, Lo WH, Yen GC. Glycyrrhizic acid and 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid modulate lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response by suppression of NF-κB through PI3 K p110δ and p110γ inhibitions. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:7726–7733. doi: 10.1021/jf2013265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster D. A study of the interaction of bromocresol green with isolated serum globulin fractions. Clin Chim Acta. 1974;53:109–115. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(74)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei XJ, Hu TJ, Chen JR, Wei YY. Inhibitory effect of carboxymethylpachymaran on cyclophosphamide-induced oxidative stress in mice. Int J Biol Macromol. 2011;49:801–805. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger C, Kaplan A, Rubaltelli FF, Hammerman C (1984) Alkaline phosphatase. Clin Chem. The C.V. Mosby Co. St Louis, Toronto. Princeton. 1094–1098

- Yousefipour Z, Ranganna K, Newaz MA, Milton SG. Mechanism of acrolein-induced vascular toxicity. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;56:337–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Lu Y, Zheng S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ cross-regulation of signaling events implicated in liver fibrogenesis. Cell Signal. 2012;24(3):596–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]