Abstract

Purpose

To develop regression models for outcomes with truncated supports, such as health-related quality of life (HRQoL) data, and account for features typical of such data such as a skewed distribution, spikes at one or zero, and heteroskedasticity.

Methods

Regression estimators based on features of the Beta distribution. Firstly, we present both a single equation and a two-part model, along with estimation algorithms based on maximum-likelihood, quasi-likelihood and Bayesian Markov-chain Monte Carlo methods. A novel Bayesian quasi-likelihood estimator is proposed. Secondly, we present a simulation exercise to assess the performance of the proposed estimators against ordinary least squares (OLS) regression for a variety of HRQoL distributions that are encountered in practice. Finally, we assess the performance of the proposed estimators by using them to quantify the treatment effect on QALYs in the EVALUATE hysterectomy trial. Overall model fit is studied using several goodness-of-fit tests such as Pearson’s correlation test, Link and Reset tests and a modified Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

Results

Our simulation results indicate that the proposed methods are more robust in estimating covariate effects than OLS, especially when the effects are large or the HRQoL distribution has a large spike at one. Quasi-likelihood techniques are more robust than maximum likelihood estimators. When applied to the EVALUATE trial, all but the maximum likelihood estimators produce unbiased estimates of the treatment effect.

Conclusion

One and two-part Beta regression models provide flexible approaches to regress the outcomes with truncated supports, such as HRQoL, on covariates, after accounting for many idiosyncratic features of the outcomes distribution. This work will provide applied researchers with a practical set of tools to model outcomes in cost-effectiveness analysis.

Keywords: Regression, Quality of Life, QALYs, Beta distribution, Quasi-likelihood, Bayesian

1. Introduction

In cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), treatment effects on costs and health outcomes and the heterogeneity in these effects across observed patients’ characteristics are often estimated using regression estimators. A large literature exists on how to develop and identify appropriate regression models for cost data, primarily developed to deal with the idiosyncrasies in the distribution of costs (e.g. non-negative values, skewness to the right and heteroskedasticity) that make the use of additive models and ordinary least squares regression (OLS) inapplicable to such data.[1–5] However, less attention has been paid to the appropriate use of regression estimators on the health outcomes side of the cost-effectiveness equation, especially when dealing with generic Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs),a despite these sharing many of the idiosyncrasies observed in costs data.

HRQoL data are typically characterized by a truncated support at both ends of the distribution (usually ranging between 0 and 1). They are typically negatively skewed, with most of the sample’s HRQoL values lying at the higher end of the measurement scale and some observations displaying extremely low levels of HRQoL. In fact, much like costs data where there usually is a spike at zero, we often see a spike at one in HRQoL data. Examples of these are the EQ5D[6] and SF6D[7] instruments. Right-skewed distributions of HRQoL are occasionally observed among certain groups of patients (e.g. terminally ill patients or individuals with chronic conditions) where most of the individuals in the sample report poor health states. Spikes at zero in such cases are usually not observed. In any case, heteroskedasticity is an integral part of such limited dependent variables.

The primary goal of this paper is to develop a particular class of regression models based on Beta distribution (originally proposed by Mullahy [8] for such applications) to address the aforementioned characteristics of the HRQoL data.b While a wider range of regression models has been proposed to analyze HRQoL data, [9–13] we compare the performance of the proposed models only against ordinary least squares (OLS) 0regression. There are two main reasons for this. First, because OLS has been used in the majority of the applications that analyzed HRQoL and QALYs, and second because recent simulation studies[14] found OLS to be superior to many of the alternative approaches that have been proposed. The Beta distribution is a very flexible starting point in that it allows modeling left and right skewed (and heteroskedastic) distributed outcomes.

All our regression models fall under the purview of the generalized linear model (GLM),[15–17] although we often do not rely on full distributional assumption. For example, we study the quasi-likelihood estimator for a Beta-based mean-variance model that is similar to maximizing a Bernoulli likelihood function. Such regressions are also popular in the econometrics literature under the name of “fractional models”. [17] Our choice is dictated by the fact that a Beta regression model has been found to be superior to alternative regression strategies in comparative studies[18, 19] although full distributional assumptions for the Beta distribution have been found to be restrictive.[20]

The rationale for moving beyond a standard linear regression model, often estimated using least squares minimization, is that predictions from such a model are never guaranteed to lie within the unit interval even when non-linearity in responses may be addressed using added interaction terms. Consequently, these out-of-range predictions may yield inconsistent estimates of covariate effects. For binary data, similar limitations of the linear probability models have led to the development of the logit and the probit models.

We propose both a single equation and a two-part version of the Beta regression estimator, with the two-part model extension developed to address the challenges posed by the presence of a spike at one in the HRQoL distribution. This paper defines incremental and marginal effects of covariates on the mean HRQoL and shows how to estimate these effects and associated standard errors. Algorithms based on maximum-likelihood (MLE), quasi-likelihood (QMLE) and Bayesian Markov-chain Monte Carlo (McMC) estimation methods are developed in this paper. We also propose a novel Bayesian QMLE approach to model such data. Relevant codes to implement these methods are produced in STATA[21] (for the MLE and QMLE) and WinBUGs [22] (for McMC estimation) and reported in the appendix. Finally, we discuss choice among alternative estimators through a variety of goodness of fit measures.

In the next section, we motivate the readers by illustrating a typical HRQoL distribution that arises within a randomized controlled clinical trial context. We then build on this early example to compare the effect of alternative regression models in estimating treatment effects on HRQoL. We further motivate the reader by illustrating a variety of shapes that HRQoL distributions can take in real applications. Section 3 lays out the model’s definition, basic assumptions and estimation methods for model parameters and the marginal and incremental effects. Section 4 presents a simulation study comparing the performance of the proposed estimators under different data generating processes. In Section 5, we illustrate the application of the proposed method to the analysis of HRQoL data from the case study presented in Section 2.

2. Observed Distribution of HRQoL and QALYs in Real Applications

The EVALUATE trial is the largest comparison of laparoscopic-assisted hysterectomy with standard methods yet undertaken. Details of the results of the clinical and economic analyses from the trial have been published elsewhere.[23, 24] The time horizon for this initial analysis was one year. In this paper, we revisit the comparative effectiveness of abdominal laparoscopic assisted hysterectomy (ALH; n = 487) relative to abdominal hysterectomy (AH; n = 263) in women for whom the latter would be the conventional procedure of choice. QALYs were calculated, for each participant in the trial, on the basis of her responses to the EQ-5D[6] at baseline, and at up to three points post-operatively (six weeks, four months and one year). Given the time horizon of the analysis, total QALYs remained undiscounted. Administrative censoring will be ignored in the present application for simplicity.

Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics for the baseline characteristics of patients in the trial as well as their total QALY for the comparison of interest. Figure 1 shows the histogram of the QALY by treatment groups. Within each treatment group, QALYs were negatively skewed. The QALY distribution in the ALH group appears to have a greater skewness and kurtosis than the AH group (ALH: skewness = −1.9, kurtosis = 7.6; AH: skewness = −2.4, kurtosis = 12.0).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the EVALUATE trial (selected covariates)

| AH (N=263)

|

ALH (N=487)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| % or Mean (SD) | % or Mean (SD) | |

| Smoker (%) | 51 (19.4) | 58 (11.9) |

| Unexpected pathology (%) | 13 (4.9) | 22 (4.5) |

| Age (years): mean (sd) | 41.3 (7.65) | 41.6 (6.94) |

| BMI (Kg): Mean (sd) | 25.89 (5.49) | 26.57 (5.15) |

| QALYs = 1 (%) | 3 (1.1) | 8 (1.6) |

| Total QALYs at 1 year: Mean (sd) | 0.861 (0.138) | 0.870 (0.133) |

Figure 1.

Distribution of QALYs by treatment arms of Abdominal hysterectomy (AH) and Laparoscopic assisted hysterectomy (ALH) in the EVALUATE trial

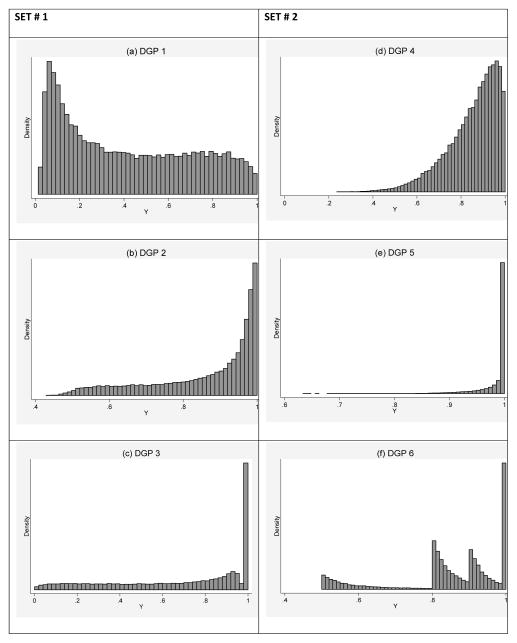

Other plausible HRQoL data distributions typically encountered in real practice are illustrated in Figure 2. These distributions jointly illustrate many of the idiosyncratic characteristics that we discussed in the introduction.

Figure 2.

Gallery of distributions for generic and disease-specific quality of life from selected clinical trials and observational studies.

3. Regression Estimators for Quality of Life Data

3.1. Model

Consider N iid observations (Yi, Xi), where Yi is a non-negative response variable with Y ∈ [0,1]d, and Xi = (Xi1, …, Xip)T is a vector of covariates that may include an intercept. Interest here is in modeling the mean function μ(x) ≡ E(Yi | Xi = x) and functionals thereof. Two particular models for the mean function are proposed: a single-equation and a two-part model.

3.1.1. Single-Equation Model

Letting μi = μ(Xi), we posit a generalized linear model (GLM) wherein and β is a p×1 vector of regression parameters. Here, the logit link function is selected due to the unit-support of the outcome variable.f The logit is a strictly monotone differentiable link function that relates μi to the linear predictor ηi.

A special case of a single equation model is the linear model where the link function is identity, .

3.1.2 Two-part Model

As discussed earlier, HRQoL distributions often carry a spike at 1 (e.g. Figure 2(a)).h In such cases, modeling the complement Y′ = (1 − Y) is most convenient, in that the spike is moved to zero and the overall expectation E(Y′) = (1 − E(Y)) is then given by:

| (1) |

For each individual i, can be modeled using a traditional logit or probit model, while can be modeled using the GLM described above.

3.2. Parameters estimation in the Single-Equation Model

For a linear model, the traditional estimation technique follows the least squares regression (LQ), which is semi-parametric in nature. Coefficient estimates are obtained by minimizing the sum of squares of residuals from the regression model, i.e. . Although it is not required that Y be normally distributed for such a least squares estimation method, the support of Y is not assumed to be restricted and therefore may not properly represent the distribution of Y that naturally has a [0,1] range.

As indicated in the introduction, the Beta distribution is a natural candidate for modeling the distribution of Y as it supports the (0,1) range, while handling both negatively and positively skewed distributions. Assuming that Yi ~ Beta(μi, φ), with mean μi = E(Yi), μi ∈ [0,1], and variance

| (2) |

with φ = 1/(1 + ξ) representing the over-dispersion term, one can write the Beta density function as e

| (3) |

One obvious caveat of the Beta distribution standard formulation is that by definition it excludes the values 0 and 1 from its support, i.e. Y ∈ (0,1). However, this limitation can be overcome using quasi-likelihood techniques that do not require the full distributional characteristics of the Beta but only its first and second moments (as described below).

It is interesting to contrast the likelihood function in (3) to that of a Bernoulli likelihood where . Although the maximum likelihood estimator for these two distributions may be dissimilar, quasi-likelihood estimators, as shown below, are identical as they share the same mean and variance function models.

3.2.1 Estimation using Maximum Likelihood (Beta-MLE)

Parameters estimation in the Beta regression can be carried out via maximum-likelihood (ML) techniques. The log likelihood function of the Beta, following equation (2), can be written as

| (4) |

One can solve for the parameter values using the first and the second derivatives of the log-likelihood function with respect to the parameters and follow a Newton-Raphson or a Fisher scoring algorithm for the maximum estimation procedure. As evident from (4), values of 0 and 1 cannot be supported by the distribution of Y. A computational solution to this problem often used in practice is to add a very small positive (negative) noise (~1.0E-06) to values of zero (one) to facilitate the MLE (this is automatically implemented in our STATA code). The same solution can be implemented for Bayesian estimation purposes as described in 3.2.3 below.

3.2.2. Estimation using Quasi-Likelihood (Beta-QMLE)

The quasi-likelihood approach can overcome the problems of excluding values of 0 and 1 in the Beta regression. It also relaxes dependence on the full distributional assumption as in the maximum likelihood-based estimator. In the quasi-likelihood approach, the regression parameters are estimated using the well-known quasi-score equations.[15]

| (5) |

McCullagh and Nelder showed that solving equations (5) is equivalent to maximizing a quasi-likelihood function that behaves in many ways as a likelihood function for the regression parameters.[16] Note that using the mean-variance relationship of a Beta distribution generates a quasi-score equation (given in (5)) that is identical to the maximum likelihood score equation under a Bernoulli likelihood function [17] with an additional over-dispersion parameter ξ.

We use estimating functions for the over-dispersion parameter ξ that is unbiased and therefore provide consistent estimators of ξ under the assumption that the mean model μi and the variance model h(μi; ξ) are correct.[25, 26] g,

| (6) |

Define and the extended estimating function for γ as . We estimate γ by solving for Gγ = 0, which yields the estimator γ̂N. Under mild regularity conditions, as N → ∞ and (γ̂N − γ0) is asymptotically normal with mean 0 and covariance matrix AN given by

| (7) |

Replacing γ by γ̂N and with in the above equation yields a sandwich estimator of the variance-covariance of γ̂N [27, 28].

3.2.3. Estimation using Bayesian McMC

There are several advantages (and some potential caveats) associated with estimating the proposed models within a Bayesian framework. These have been well rehearsed in various textbooks (see for instance [29]) and more recently by Luce and O’Hagan.[30] Briefly, compared to frequentist methods, a Bayesian approach (i) offers a more natural and intuitive framework for statistical inference; (ii) can make use of all existing evidence prior to the experiment by using prior distributions; (iii) can address more complex models (that sometimes cannot be examined under a standard classical framework); and (iv) it is ideal for decision making given the way we can interpret the output of Bayesian analyses. On the other hand, one may need to be very careful when using Bayesian methods in making sure that subjectivity is not an issue and the application of the methods is as transparent as it can possibly be.

Traditional Bayesian models usually assume parametric distributions for the outcomes of interest. For example, for modeling outcomes such as the generic HRQoL measure EQ5D, one can assume that the outcome follows a Beta distribution. On the other hand, following the quasi-likelihood principle, it is often more robust to relax such distribution assumptions. Since quasi-likelihood estimation based on Beta distribution corresponds to a Bernoulli likelihood model, one can “trick” the WinBUGS software to implement a quasi-likelihood estimator.[31] We present both versions here.

Bayesian Beta-MLE

The Bayesian Beta regression model can be expressed as

| (8) |

Following the likelihood function in (3), the posterior joint distribution for (β, ξ) is given as

| (9) |

For priors, we assume p(β, ξ) = p(β)p(ξ) and define vague priors on the unknown parameters. More specifically, the regression coefficients in β are assigned Normal distributions with mean zero and large variance (see the code in appendix). Similarly, instead of specifying a prior for ξ, one can directly specify a prior for the over-dispersion parameter φ = 1/(1 + ξ), which can be assumed to follow a Gamma or a Uniform distribution with large dispersion.

This model can be estimated in Bayesian terms using McMC simulation techniques,[32] via the freely available software WinBUGS 1.4.3,[22] by iterative sampling of the full conditional distributions p(β | ξ, y) ∝ L(β, ξ)p(β) and p(ξ | β, y) ∝ L(β, ξ)p(ξ). Posterior inference for the parameter β, ξ and the mean response μ(x) can be easily obtained in WinBUGS.

Bayesian Beta-QMLE

The idea behind Bayesian QMLE is to specify a Bernoulli-type likelihood for maximization. Since our outcome variable is not a 0/1 (binary) variable, we follow the zeros-trick in WinBUGS to implement this.

First, we create a new variable Zi that takes the value of zero for all observations; then we specify the following model:

| (10) |

Since the likelihood for the Poisson distribution when Zi = 0 is given by e−λi, maximizing the Poisson likelihood corresponds to maximizing the Bernoulli likelihood given by the second expression in (10).

All priors are specified the same way as in the Bayesian MLE estimation.

3.3. Parameters estimation in the Two-part Model

Estimation for the second part of the two-part model follows the same estimation methods described under two-part models (LQ, Beta-MLE, Beta-QMLE, Bayesian Beta-MLE and Bayesian Beta-QMLE).

For the first part of the two-part model, we can use a traditional logistic regression to model the 0/1 binary outcome. The logistic regression can be implemented either using a full maximum likelihood method, quasi-likelihood estimation technique or using Bayesian analogs of these methods. Details of estimating a logistic regression using these methods are standard practice and their details can be found elsewhere[33].

3.4. Estimation of Marginal and Incremental Effects

Since the regression coefficients from single and two-part models have different interpretations, it is useful to focus on a metric that would be comparable across models. The marginal and incremental effects of a covariate on outcomes on their original-scale are two such metrics. The estimation of marginal and incremental effects follows the procedures detailed in Basu and Rathouz.[26] The marginal effect, ψj of any continuous covariate Xj on Y is the estimated partial derivative of μ(xi) with respect to a covariate Xj, averaged over all i. For the model proposed in 3.1.1 (single-equation model), an estimator of the marginal effect is given by

| (11) |

Here the hat (ˆ) on μ̂ indicates that the β coefficients have been estimated and the hat on ÊX indicates that the sample expected value has replaced the population expected value. To estimate the incremental effect, Δj of an indicator variable Xj, we use the method of recycled predictions.[34] This method estimates Δj as

| (12) |

where Xi,−j represents the vector of all other X’s except for Xi,j. Robust variance estimators for the marginal and incremental effect estimators can be obtained using Taylor series approximations (formulas are given in the Appendix). Alternatively, variance estimators can be obtained using non-parametric methods such as bootstrap, or using McMC.

For a two-part model (section 3.1.2), the marginal effect is computed using the chain rule used in expressing the partial derivative of a product. Specifically, if μ̂1(X) and μ̂2(X) are the predicted means and α̂ and β̂ are the estimated coefficients from the two parts respectively, then an estimator of the marginal effect is given by

| (13) |

An estimate of the incremental effect in a two-part model is identical to that given in (12), where μ̂(Xi,−j, Xij = j) = μ̂1(Xi,−j, Xij = j)·μ̂2(Xi,−j, Xij = j), j = 0,1. Again, standard errors for these effects in two part models can be more conveniently estimated via simulation methods (e.g. bootstrap or McMC).

4. Simulations

4.1. Designs

Our primary goal is to estimate the effect of a continuous covariate X on the outcome Y ∈ [0,1]. We generate X using a uniform distribution between 0 and 1 and Y following a variety of distributions. The data generating mechanisms (DGPs) for Y are broadly grouped into two sets. In the first set, the true marginal effect of a standard-deviation change in X was designed to be much greater than 0.03. In the second set, the data were designed for a true marginal effect of a standard deviation change in X to be less than 0.03. The 0.03 cut-off was chosen arbitrarily, with the primary rationale being that in outcome distributions that are truncated at both sides, the effect of a covariate is usually small, in which case the biases due to model misspecification may not appear so obvious. Each of the DGP from either DGP set carries the typical idiosyncratic characteristics of HRQoL data described in the introduction.

Specifically, the following data generating processes were used:

SET 1

DGP 1: Y ~ Beta(α = exp(2), β = exp(5·X)), E(Y | X) = exp(2)/(exp(2) + exp(5·X))

DGP 2: Y ~ Beta(α = exp(5), β = exp(5·X)), E(Y | X) = exp(5)/(exp(5) + exp(5·X))

-

DGP 3: Y ~ (1 − p)·1 + p·(1 − Y1),

where Y1 ~ Beta(α = 2, β = 5·X)

and p = 1 − FU{0.20·exp(0.5·X)}, U ~ Uniform(0,1); FU = CDF

Interest lies in estimating the marginal effect of X on Y: Δ = EX{∂E(Y | X)/∂X}. The true values for this quantity are −0.833, −0.493, and 0.673 respectively and the corresponding values for a standard deviation change in X are −0.24, −0.14 and 0.19 respectively.

SET 2

DGP 4: Y ~ Beta(α = exp(2), β = exp(0.5·X)), E(Y | X) = exp(2)/(exp(2) + exp(0.5·X))

DGP 5: Y ~ Beta(α = exp(3), β = 0.01·exp(5·X)), E(Y | X) = exp(3)/(exp(3) + 0.01·exp(5·X))

-

DGP 6: Y ~ A mixture of

{1−0.01·Beta(α = exp(0.5·X), β = 1)} with probability 0.20,

{1−0.10·Beta(α = exp(2.0·X), β = 1)} with probability 0.20,

{1−0.20·Beta(α = exp(2.5·X), β = 1)} with probability 0.40, and

{1−0.50·Beta(α = exp(3.0·X), β = 1)} with probability 0.20.

Again, interest lies in estimating the marginal effect of X on Y: Δ = EX{∂E(Y | X)/∂X}. The true values for this quantity are −0.063, −0.068, and −0.087 respectively and the corresponding values for a standard deviation change in X are −0.02, −0.02 and 0.025 respectively.

4.2. Estimators

We compare the performance of five estimators using a single equation model under each DGP. These estimators are: 1) simple OLS regression with an identify link, 2) Beta MLE; 3) Beta QMLE; 4) Bayesian-Beta MLE and 5) Bayesian-Beta QMLE. These estimators are described in Section 3.2. Under DGPs 3 and 5, because of the spike at zero in the distribution of Y, we additionally run two estimators for a two part model: 6) 1st part Logistic regression & 2nd part Beta QMLE; 7) 1st part Bayesian Logistic regression & 2nd part Bayesian-Beta QMLE. These estimators are described under Section 3.3. We also study the use of Beta-MLE for the two-part model but do not present results for clarity as the results for Beta-MLE from the single equation models carry over to the two-part ones. Incremental effect from the two-part models were estimated using (11) and (13).

4.3. Evaluations

We generate 1,000 replicate samples of 500 each under each data generating mechanism. For each replicate data set and under each of five different estimators (k = 1,2,..5), we estimate the marginal effect, ψ̂k with respect to X that is computed using (11). For Bayesian estimations, we run three chains and discard the first 5000 iterations from each chain as burn-ins. We then compute the posterior mean of the parameters over the next 10000 replicates from each chain that were sampled with a thinning of 5.i We report the % mean bias (and 95% CI) in estimating ψ under each method that is given by (ψ̂k − ψTrue)·100/ψTrue. (95% central confidence interval (CCI) calculated using the empirical distribution of Δ̂k across replicates).

We also report and compare the root mean squared error (RMSE) for predictions, , under each model averaged over all replicates from a DGP. All work was done using Stata 10.0.[21] and WinBUGS 1.4.3.[22] Bayesian estimations were done on the same replicate data sets as other estimators. We use the winbugsfromstata package in Stata to iteratively call WinBUGS from within Stata 10.0, import the output from WinBUGS and produce graphics.[35]

4.4. Results

Typical distributions arising from each of the four DGPs are summarized in Figure 3. DGP 1 generates a Beta distribution that is positively skewed; all the remaining DGPs generate distributions that are negatively skewed; DGP 6 generates a categorical distribution with multiple modes and DGPs 3 and 5 generate modified Beta distributions with a large spike at one.

Figure 3.

Typical distributions for the data generating processes used in simulations.

Table 2 presents our simulation results for the SET # 1 DGPs where the true marginal effects of a standard deviation change in X were all much greater than 0.03. We find that linear OLS provides biased results for estimating the marginal effect under DGPs 1, 2 and 3. The (single equation) Beta MLE does well in terms of bias and RMSE on data from DGPs 1 and 2 given that it is the minimum variance unbiased estimator (MVUE) for these data. However, Beta MLE shows statistically significant bias under DGP 3 as this does not correspond to a Beta distribution. The (single equation) Beta QMLE does reasonably well under all DGPs. The Bayesian counterparts of the (single equation) MLE and QMLE estimators mirror the results from the frequentist (single equation) Beta MLE and QMLE estimators. One surprising exception is that we find the (single equation) Bayesian MLE to generate biased estimates under DGP 2, which itself is a Beta distribution. The biases were consistent across alternative specification of priors (e.g. we also tried the prior, exp(β)/(1 + exp(β)) ~ Uniform(0,1)). The (single equation) Beta QMLE again performs well and shows no sign of bias. The two-part models, both the frequentist and the Bayesian approach, perform better than any other estimator under DGP 3 where there was a large spike at one.

Table 2.

Simulation results for SET # 1 DGPs

| DATA: | DGP 1 | DGP 2 | DGP 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Model | Estimators | Mean % Bias (95% CCI) | Mean % Bias (95% CCI) | Mean % Bias (95% CCI) |

| Single-Equation | Linear OLS | 13.7 (9.9, 17.3) | −9.1 (−13.5, −4.7) | −12.3 (−22.9, −1.2) |

| Single-Equation | Beta MLE | −0.5 (−4.2, 3.5) | 0.4 (−7.4, 8) | 67.7 (53.1, 80.1) |

| Single-Equation | Beta QMLE | 0.01 (−3.9, 4.0) | 0.1 (−7.7, 7.7) | −5.1 (−14.0, 4.2) |

| Single-Equation | Bayesian MLE | −3.5 (−8.0, 0.9) | −12.4 (−18.0, −6.9) | 67.5 (56.2, 79.0) |

| Single-Equation | Bayesian QMLE | −0.1 (−4.8, 4.8) | −0.6 (−12.9, 7.7) | −5.2 (−13.7, 3.1) |

| Two-part | Two-part Beta QMLE | - | - | 0.2 (−9.2, 10.2) |

| Two-part | Two-part Bayesian QMLE | - | - | 0.05 (−8.4, 9.2) |

|

| ||||

| Model | Estimators | RMSE | RMSE | RMSE |

|

| ||||

| Single-Equation | Linear OLS | 0.1051 | 0.0592 | 0.2268 |

| Single-Equation | Beta MLE | 0.0989 | 0.0222 | 0.2838 |

| Single-Equation | Beta QMLE | 0.0982 | 0.0221 | 0.2249 |

| Single-Equation | Bayesian MLE | 0.1004 | 0.0421 | 0.2835 |

| Single-Equation | Bayesian QMLE | 0.1011 | 0.0312 | 0.2256 |

| Two-part | Two-part Beta QMLE | - | - | 0.2244 |

| Two-part | Two-part Bayesian QMLE | - | - | 0.2251 |

The true values for the marginal effect under DGPs 1–3 are −0.833, −0.493, and 0.673 respectively; Bold face indicates significant bias at the 5% level.

In terms of efficiency, the RMSE for predictions were fairly similar across all estimators. The Bayesian estimators showed slightly higher RMSEs. However, the dispersion in estimating the marginal effect varied widely across estimators as evident from the 95% CCI for the biases. In DGPs 1 and 2, Bayesian QMLE produces slightly wider 95% CCI while in DGPs 3 the Bayesian QMLE produced better results.

Table 3 presents our simulation results for the second set of DGPs where the true marginal effects of a standard deviation change in X were all less than 0.03. Here we find OLS to perform well and estimate the marginal effect without bias except under DGP 5, where there is a large spike at one. Under DGP 5, both OLS and the MLE methods show significant bias. All estimators perform well under DGP 4, given the additive nature of the data generation process. In terms of efficiency, the RMSE for predictions were again fairly similar across all estimators.

Table 3.

Simulation results for SET # 2 DGPs

| DATA: | DGP 4 | DGP 5 | DGP 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Model | Estimators | Mean % Bias (95% CCI) | Mean % Bias (95% CCI) | Mean % Bias (95% CCI) |

| Single-Equation | Linear OLS | −0.5 (−57.4, 59.4) | −24.3 (−38.1, −8.9) | −1.4 (−47.5, 46.7) |

| Single-Equation | Beta MLE | 4.1 (−47.4, 55.0) | −36.3 (−50.2, −21.7) | 30.5 (−13, 71) |

| Single-Equation | Beta QMLE | −0.4 (−57.4, 59.6) | 0.9 (−22.9, 27.8) | −1.6 (−47.4, 46.6) |

| Single-Equation | Bayesian MLE | 2.75 (−47.0, 53.3) | −14.0 (−26.7, −0.7) | 2.8 (−1.0, 5.7) |

| Single-Equation | Bayesian QMLE | −2.26 (−55.7, 55.3) | 8.85 (−17.9, 37.8) | −0.06 (−5.4, 4.0) |

| Two-part | Two-part Beta QMLE | - | −8.4 (−31.2, 17.2) | - |

| Two-part | Two-part Bayesian QMLE | - | 2.0 (−23.2, 30.3) | - |

|

| ||||

| Model | Estimators | RMSE | RMSE | RMSE |

|

| ||||

| Single-Equation | Linear OLS | 0.1138 | 0.0263 | 0.1409 |

| Single-Equation | Beta MLE | 0.1139 | 0.0256 | 0.1413 |

| Single-Equation | Beta QMLE | 0.1138 | 0.0248 | 0.1410 |

| Single-Equation | Bayesian MLE | 0.1139 | 0.0267 | 0.1415 |

| Single-Equation | Bayesian QMLE | 0.1158 | 0.0266 | 0.1429 |

| Two-part | Two-part Beta QMLE | - | 0.0249 | - |

| Two-part | Two-part Bayesian QMLE | - | 0.0266 | - |

The true values for the marginal effect under DGPs 4–6 are −0.063, −0.068, and −0.087 respectively; Bold face indicates significant bias at the 5% level.

4.5. Summary of results

Our simulations show that one and two-part Beta regression models, especially the quasi-likelihood estimators, provide flexible approaches to regress the mean of an outcome with truncated support such as HRQoL on a covariate. We find substantial benefits, both in terms of bias and efficiency, of these regression estimators over traditional OLS approaches.

The fact that (single equation) Beta-MLE and Beta-QMLE produces different results in DGPs 3 and 5 indicates that the issue is more than just misspecification of the logit mean function. Results from these DGPs highlight the advantage of QMLE over MLE methods.

Moreover, both the linear and the logit specifications only provide approximations to the conditional mean under DGP 6. However, both these approximations turn out to be good enough for estimating the marginal effect of X because the effect is small and the residual bias cannot be detected with any precision. On the other hand, in DGP3, where both the linear and the logit specifications provide again approximations to the true mean function, the linear approximation fails while the logit is successful. Here, the bias with linear approximation is larger than that with the logit specification, and this bias is detected because the overall effect is large.

One can conclude that when the marginal effects of covariates are small, the biases in estimating marginal effect using OLS may also be small, even if OLS does not provide the optimal fit to the data. However, this luxury for OLS no longer holds when there is a large spike at one. Overall, the Beta-based regression estimators and especially their quasi-likelihood based variants provide a flexible approach to model HRQoL data. In specific instances, it is quite possible that even the logit link employed by the Beta-based regression may provide poor fit to the data. Therefore, a rigorous set of goodness of fit test should always be applied to study the appropriateness of a model and to choose among alternative estimators. We present a variety of such tests in our empirical section.

5. Empirical Example

Let us now turn the attention to the case study introduced in section 2: the EVALUATE trial. While the two groups are well balanced in many baseline characteristics, Table 1 suggests that the laparoscopic assisted arm (ALH) includes a higher proportion of current smokers, and women who were found to have unexpected pathologies during surgery. In terms of QALYs which is the outcome of interest here a higher proportion of women in the ALH arm had a computed QALY of 1 at the end of the follow up period.

We applied the same regression methods used in our simulations and as discussed to the EVALUATE data. In addition to the treatment indicator, we adjusted for baseline values of smoking, unexpected pathology, age and BMI (Table 1). Specifically, we compare the performance of five estimators using a single equation model. These estimators are: 1) simple OLS regression, 2) Beta MLE; 3) Beta QMLE; 4) Bayesian-Beta MLE and 5) Bayesian-Beta QMLE. In addition we ran two estimators for a two part model: 6) 1st part Logistic regression and 2nd part Beta QMLE; 7) 1st part Bayesian Logistic regression and 2nd part Bayesian-Beta QMLE. These estimators are described under Section 3.3.

Table 4 reports the incremental (treatment effect) estimates together with the root mean squared error (RMSE) and the predicted QALYs (and related standard deviation) for each treatment group in the EVALUATE trial. In order to facilitate model comparison we evaluate the following goodness of fit criteria:

Table 4.

Predicted QALYs and Incremental (treatment effect) estimates in the EVALUATE trial.

| Model | Estimators | AH (N=263) Mean QALY [SD] |

ALH (N=487) Mean QALY [SD] |

Incremental effect [SD] | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Equation | Linear OLS | .862 [.008] | .870 [.006] | .008 [.016] | 0.1249 |

| Single-Equation | Beta MLE | .850 [.009] | .880 [.006] | .030* [.014] | 0.1300 |

| Single-Equation | Beta QMLE | .861 [.008] | .870 [.006] | .009 [.011] | 0.1260 |

| Single-Equation | Bayesian MLE | 0.850 [0.009] | 0.880 (0.006) | .030* [.009] | 0.1340 |

| Single-Equation | Bayesian QMLE | 0.862 [0.023] | 0.869 (0.015) | .007 [.028] | 0.1371 |

| Two-part | Two-part Beta QMLE | .864 [.008] | .871 [.006] | .007 [.016] | 0.1260 |

| Two-part | Two-part Bayesian QMLE | 0.863 [0.023] | 0.868 [0.015] | .005 [.150] | 0.1371 |

95% Central interval excludes zero.

The mean residuals across deciles of the corresponding linear predictor η̂ = xTβ̂. By looking at the pattern in the residuals as a function of η̂, we can determine whether there is a systematic pattern of misfits in the forecasts. A formal version of this test is provided by the test of goodness of fit proposed by Hosmer and Lemeshow,[36] and is implemented by using an F-test that the mean residuals across all 10 of the deciles are not significantly different from zero. Note that the original Hosmer and Lemeshow test was devised on a binary outcome whose mean possesses similar distributional characteristics as the mean of a fractional response. If the residual pattern is u-shaped then there is evidence for a more nonlinear response than was assumed.

We present the Pearson correlation between the raw-scale (y-scale) residual and μ̂(x). If this statistic is significantly different from zero, then the model is providing a poor prediction of μ(x).

A more parsimonious test for nonlinearity is Pregibon’s Link Test.[37] Based on the initial estimate of the regression coefficients, η̂ and its square are included as the only covariates in a second version of the model. If there is no additional non-linearity in the specification, then the coefficient on the square of the linear predictor should not be significantly different from zero.

Similar to the Link test, another test of misspecification is the Ramsey’s Reset Test.[38] We run a modified version of the Reset test where η̂, its square and its cube are included.j If there is no additional non-linearity in the specification, then the joint test for the coefficients on the higher-order terms should not be significantly different from zero.

For the two-part models, the Hosmer-Lemeshow and the Pearson correlation tests were run based on the overall predictions of QALYs generated after combining estimates from both parts of the two-part models.

Examining the incremental effects reported in Table 4 for the EVALUATE trial data, it appears that the frequentist and Bayesian Beta MLE produced identical results showing a significant improvement of 0.03 QALYs for patients receiving ALH versus AH. In contrast, OLS, frequentist and Bayesian Beta QMLE and their two-part extensions all estimated the incremental effect to lie between 0.004 – 0.007, which was not statistically significant under any of the estimators. To further understand the differences in results we look at the goodness of fit tests in Table 5 and Figure 4. We suppressed test results for the Bayesian estimators as they were identical to their frequentist counterparts. Table 5 shows that the all estimators passed all the tests with the exception of the Beta MLE which failed the Pearson correlation test showing significant correlation between residuals and prediction. This is evident from Figure 4 which plots the mean residuals over the deciles of the linear predictor. Beta MLE underestimated the mean at the lower end of the distribution while overestimating the mean at the higher end of the distribution. Our empirical results are consistent with the simulation results in that we found the Beta MLE to produce biased estimates of the incremental effect. This is probably due to the continuity correction implemented by subtracting a small noise to the observations with QALY=1 and the fact that the two treatment groups differ in the proportion of observations with QALY=1. Also, since the correct incremental effect appears to be small and insignificant in this example and the distribution of QALY did not have a spike at one, the OLS estimate of the effect is believed to be potentially unbiased.

Table 5.

Results for goodness-of-fit tests for alternative estimators.

| Model | Single-equation | Two-part | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Estimators | Linear OLS | Beta MLE | Beta QMLE | Beta QMLE |

| Hosmer and Lemeshow | ||||

|

| ||||

| F-stat (p-value) | 0.76 (0.67) | 1.14 (0.17) | 0.80 (0.63) | 0.94 (0.50) |

| Pearson correlation | ||||

| Rho (p-value) | .00000 (1.00) | −0.08 (0.03) | 0.001 (0.98) | −0.002 (0.96) |

| Link Test | ||||

| t-stat (p-value) | −1.09 (0.77) | 0.32 (0.41) | −0.08 (0.88) | - |

| Reset Test | ||||

| F-stat (p-value) | 1.14 (0.32) | 1.69 (0.43) | - | |

Figure 4. Mean residuals across deciles of linear predictors (or predictor) across alternative estimators.

*Deciles of linear predictor for OLS, MLE & QMLE;

Deciles of predictions for two-part QMLE

All models have the same root mean square error, which may indicate that this diagnostic is not of great help with limited dependent variables.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we discuss and compare the performance of a wide range of estimators that can be used to model an outcome variable with truncated support on both ends. Our focus was on modeling HRQoL and QALYs data, since these outcomes share the same features in their distributions. Our estimators are primarily based on the Beta distribution, although we also studied a quasi-likelihood estimation technique that relaxes the full distributional assumptions required by maximum likelihood based estimation methods. We present a novel Bayesian estimator that possesses the robustness of a quasi-likelihood technique. Our simulation results indicate that when the effect of a standard deviation change in covariate value is small (our rule of thumb is < 0.03) and there are no spikes at one, OLS provides an unbiased estimate of the covariate effect. When the covariate effect is large, OLS can produce substantially biased results. Although we think that such a cut-off is a conservative estimate of the threshold below which OLS may work fine, more work and simulations are needed to validate such a conclusion. When effects are large, Beta QMLE appears to be the most robust alternative. When there are large spikes at one, a two-part Beta QMLE can improve the fit and produce both unbiased and more efficient estimates of covariate effects compared to Beta QMLE. Both the Beta QMLE and the two-part Beta QMLE can be implemented using Bayesian methods, and our results still hold.

We provide detailed Stata and WinBUGS codes in the Appendix to implement each of the estimators that we studied. We hope these will provide researchers with the tools to apply and appropriately model quality of life outcomes and other data with similar features.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Basu acknowledges support from the Alan Williams Health Economics Fellowship from the University of York and research grants from the National Institute of Mental Health 1R01MH083706 and the National Cancer Institute 1RC4 CA155809-01. This work is produced by Dr Manca under the terms of a Career Development Fellowship issued by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). We are grateful for comments from two anonymous reviewers that have helped in our presentation of the scientific material. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Universities of York and Washington, NBER, the NHS, NIHR or the Department of Health in the UK.

7. Appendix

CODES: Outcome = Y, Covariate = X Stata command - betareg- can be downloaded from http://faculty.washington.edu/basua/ Full Stata code for implementing all estimators: // Linear OLS Regression reg y x, robust gen b_ols= _b[x] // Marginal effect predict mu, xb gen ols_rmse = (y-mu)^2 // Squared Error drop mu // Beta-MLE betareg y x, ml gen b_mle= _b[x] predict xb, xb gen mu = exp(xb)/(1 + exp(xb)) gen ml_rmse = (y-mu)^2 // Squared Error gen ml_me = mu*b_mle/(1+ exp(xb)) // Marginal effect drop xb mu // Beta-QMLE betareg y x gen b_qmle= _b[x] predict xb, xb gen mu = exp(xb)/(1 + exp(xb)) gen qml_rmse = (y-mu)^2 // Squared Error gen qml_me = mu*b_qmlw/(1+ exp(xb)) // Marginal effect drop xb mu // Two-part gen ind= (y > 0) * Part 1 - Logistic logit ind x, robust gen two_b1= _b[x] predict xb, xb gen mu1 = exp(xb)/(1 + exp(xb)) gen two_me1 = mu1*two_b1/(1+ exp(xb)) drop xb * Part 2 – Beta QMLE betareg y x if y > 0 gen two_b2= _b[x] predict xb, xb gen mu2 = exp(xb)/(1 + exp(xb)) gen two_me2 = mu2*two_b2/(1+ exp(xb)) drop xb gen two_me = mu1*two_me2 + mu2*two_me1 // Marginal effect gen two_mu = mu1*mu2 gen twormse = (p-two_mu)^2 // Squared Error // CALL WinBUGS from STATA count if y==0 scalar num=r(N)+1 // Identify obs. # where positive y starts sort y * Saving datasets for WinBUGS to read wbscalar, sca(num) format(%3.0f) /// saving(c:\projects\Econometrics\betareg\wbsimul4_data1.txt, replace) wbvector x y z ind, /// saving(c:\projects\Econometrics\betareg\wbsimul4_data.txt, replace) /// linesize(100) format(%-12.10f) noprint * Call WinBUGs using a script file capture shell “c:\Program Files\winbugs14\winbugs14” /par c:/projects/Econometrics/betareg/wbsimul4_script.txt * Retrieve Coda from WinBugs wbcoda, root(c:\projects\Econometrics\betareg\wbsimul4_out) /// clear chain(3) multichain collapse (mean) ml_* qml_* two_* WinBUGS Codes: // Script: Instructs WinBUGS with the sequence of commands to do MCMC display(‘log’) check(‘c:/Projects/Econometrics/betareg/wbsimul4.txt’) data(‘c:/Projects/Econometrics/betareg/wbsimul4_data1.txt’) data(‘c:/Projects/Econometrics/betareg/wbsimul4_data.txt’) compile(3) inits(1, ‘c:/Projects/Econometrics/betareg/wbsimul4_init1.txt’) inits(2, ‘c:/Projects/Econometrics/betareg/wbsimul4_init2.txt’) inits(3, ‘c:/Projects/Econometrics/betareg/wbsimul4_init3.txt’) update(5000) set(‘ml.marg’) set(‘qml.marg’) set(‘two.marg’) set(‘ml.rmse’) set(‘qml.rmse’) set(‘two.rmse’) thin.updater(50) update(500) coda(*,’c:/Projects/Econometrics/betareg/wbsimul4_out’) quit() // Main Program File: model { ## Priors for (j in 1:2) { b.mle[j] ~dnorm(0, 0.000001) b.qmle[j] ~dnorm(0, 0.000001) b.two1[j] ~dnorm(0, 0.000001) b.two2[j] ~dnorm(0, 0.000001) } si~ dunif(0.01, 10) ## Sort data by y, such that y=1 for obs #s 1 to (‘num’ -1) N <- 500 for (i in 1:N) { ## Beta- MLE y.noise[i]<- y[i] + (1- ind[i])*0.0000001 y.noise[i]~dbeta(a[i], b[i]) a[i]<-mu[i]*si b[i]<-(1-mu[i])*si logit(mu[i]) <- b.mle[1] + b.mle[2]*x[i] mle.marg[i]<- mu[i]*b.mle[2]/(1+ exp(b.mle[1] + b.mle[2]*x[i])) mle.mse[i]<- pow((y[i] - mu[i]), 2) ## Beta QMLE y.dupl[i] <- y[i] z[i]~dpois(lambda[i]) lambda[i]<- -(y.dupl[i]*log(m[i]) + (1-y.dupl[i])*log(1 - m[i])) logit(m[i]) <- b.qmle[1] + b.qmle[2]*x[i] qmle.marg[i]<- m[i]*b.qmle[2]/(1+ exp(b.qmle[1] + b.qmle[2]*x[i])) qmle.mse[i]<- pow((y.dupl[i] - m[i]), 2) ## Two-part Beta QMLE ## PART 1 y.dupl2[i]<-y[i] z.dupl[i]<-z[i] yind[i]~dbin(p.two[i], 1) logit(p.two[i]) <- b.two1[1] + b.two1[2]*x[i] } for (i in num:N) { ## PART 2 z.dupl[i]~dpois(lambda.two[i]) lambda.two[i]<- -(y.dupl2[i]*log(m.two[i]) + (1-y.dupl2[i])*log(1 - m.two[i])) logit(m.two[i]) <- b.two2[1] + b.two2[2]*x[i] } for (i in 1:N) { ## PREDICTIONS FOR TWO-PART MODEL, MADE FOR ALL OBS m.pred[i]<- exp(b.two2[1] + b.two2[2]*x[i])/(1+ exp(b.two2[1] + b.two2[2]*x[i])) mu.two[i]<-p.two[i]*m.pred[i] tw.marg[i]<- (p.two[i]*m.pred[i]*b.two2[2]/(1+ exp(b.two2[1] + b.two2[2]*x[i]))) + (m.pred[i]*p.two[i]*b.two1[2]/(1+ exp(b.two1[1] + b.two1[2]*x[i]))) tw.mse[i]<- pow((y.dupl[i] - mu.two[i]), 2) } ## Compute Marginal effects and RMSE ml.marg<-mean(mle.marg[]) qml.marg<-mean(qmle.marg[]) two.marg<-mean(tw.marg[]) ml.rmse<-sqrt(mean(mle.mse[])) qml.rmse<-sqrt(mean(qmle.mse[])) two.rmse<-sqrt(mean(tw.mse[])) }

ANALYTICAL VARIANCE ESTIMATORS

The analytical variance estimator for ψ̂j (equation (11)) will depend both on the variance of (β̂) and also on the variance of covariates X in the population of interest. The variance for the estimator in (11) is given by

| (A.1) |

In (A.1), the first term is the sample variance of ψ̂j due to using the empirical expected value over X−j, ÊX−j {Dj (μ; X−j)}, rather than the population expected value. Here X−j represent the vector of all other covariates besides Xj. The second term is due to the fact that γ is estimated. An estimator of the variance (A.1) is obtained by replacing γ with γ̂, and replacing the first term in (A.1) by

| (A.2) |

An estimator for Var(Δ̂j) analogous to (A.1) may be obtained through a similar approach.

Footnotes

We will only use the term quality of life to represent the effectiveness data. Quality adjusted life-years (QALYs) can be readily converted to a per year quality of life estimate by dividing by the number of years over which QALYs are calculated.

In this paper we focus on the analysis of HRQoL data collected alongside randomized controlled clinical trials and do not deal with the issues related to selection bias in non-randomized settings.

The methods presented here can be readily extended to outcomes with any truncated support Y ∈ [a, b] where b>a and b, a ∈ ℝ. One can scale the response variable so that Y′ = (Y − a)/(b − a). Since Y′ ∈ [0,1], one can model Y′ with the methods presented here. Note that in such cases, we can relax the assumption of nonnegativeness of Y, i.e Y ∈ ℝ.

This formulation is slightly different to the traditional formulation of a Beta density where f(Y) ∝ Yα−1(1−Y)β−1. The cross walk between these two formulae is straightforward: μ = α/(α+β) and ξ = (α+β). The formulation we use is usually suitable for a generalized linear model.

Alternative options (e.g. probit or complementary log-log link) may also be used.

The inclusion of ξ is not necessary for estimating the mean model parameters as it is just a constant scaling factor. However, its use serves two purposes: 1) a large estimated variance of ξ indicates that there might be residual heteroskedasticity that remains unaccounted for, and 2) it sets up the estimating algorithm to let ξ vary by X thereby accounting for the residual over dispersion in the variance model. We delegate these aspects to our future work.

If the spike is at zero instead, the two part model can be directly applied to Y.

In our dry-runs before the simulation, we assessed reasonable convergence of parameters values using these specifications.

We do not use the fourth power term as used in traditional Reset test due to small sample size.

Contributor Information

Anirban Basu, Departments of Health Services and Pharmacy, University of Washington, Seattle, WA and The National Bureau of Economic Research, MA, USA.

Andrea Manca, Centre for Health Economics, The University of York, York, UK

References

- 1.Manning WG. The logged dependent variable, heteroscedasticity, and the retransformation problem. Journal of Health Economics. 1998;17(3):283–95. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(98)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mullahy J. Much ado about two: reconsidering retransformation and the two-part model in health econometrics. J Health Econ. 1998 Jun;17(3):247–81. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(98)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manning WG, Basu A, Mullahy J. Generalized modeling approaches to risk adjustment of skewed outcomes data. Journal of Health Economics. 2005;24(3):465–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manning WG, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: To transform or not to transform? Journal of Health Economics. 2001;20(4):461–94. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manning W. Dealing with skewed data on costs and expenditures. In: Jones AM, editor. The Elgar companion to health economics. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd; 2006. pp. 439–46. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996 Jul;37(1):53–72. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ. 2002;21(2):271–92. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mullahy J. Department of Economics, Trinity College (mimeo) 1990. Regression models and transformations for beta-distributed outcomes. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Austin PC. A comparison of methods for analyzing health-related quality-of-life measures. Value in Health. 2002;5(4):329–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2002.54128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Austin PC. Bayesian extensions of the tobit model for analyzing measures of health status. Medical Decision Making. 2002;22(2):152–62. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0202200212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke P, Gray A, Holman R. Estimating utility values for health states of type 2 diabetic patients using the EQ-5D (UKPDS 62) Med Decis Making. 2002 Jul-Aug;22(4):340–9. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0202200412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grootendorst P. Censoring in statistical models of health status: what happens when one can do better than ‘1’. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(8):911–4. doi: 10.1023/a:1008938429316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang IC, Frangakis C, Atkinson MJ, Willke RJ, Leite WL, Vogel WB, et al. Addressing ceiling effects in health status measures: a comparison of techniques applied to measures for people with HIV disease. Health Serv Res. 2008 Feb;43(1 Pt 1):327–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pullenayegum EM, et al. Analysis of health utility data when some subjects attain the upper bound of 1: are Tobit and CLAD models appropriate? Value in Health. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00695.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wedderburn RWM. Quasi-likelihood functions, generalized linear models, and the Gauss-Newton method. Biometrika. 1974;61:439–47. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized Linear Model. 2. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papke LE, Wooldridge JM. Econometric Methods for Fractional Response Variables With an Application to 401 (K) Plan Participation Rates. Journal of Applied Econometrics. 1996;11(6):619–32. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kieschnick R, McCullough BD. Regression analysis of variates observed on (0,1): percentages, proportions and fractions. Statistical Modelling. 2003;3:193–213. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smithson M, Verkuilen J. A better lemon squeezer? Maximum-likelihood regression with beta-distributed dependent variables. Psychol Methods. 2006 Mar;11(1):54–71. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gourieroux C, Monfort A, Trognon A. Pseudo-maximum likelihood methods: theory. Econometrica. 1984;52(3):681–700. [Google Scholar]

- 21.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lunn DJ, Thomas T, Best N, Spiegelhalter DJ. WinBUGS - A Bayesian modelling framework: Concepts, structure, and extensibility. Statistics and Computing. 2000;10(4):325–37. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garry R, Hawe J, Abbott J, et al. The EVALUATE study: randomised trials comparing laparoscopic with abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy. British Medical Journal. 2004;328:129–33. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37984.623889.F6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sculpher MJ, Manca A, Abbott J, Fountain J, Mason S, Garry R. The Cost-Effectiveness of Laparoscopic-Assisted Hysterectomy In Comparison with Standard Hysterectomy: The EVALUATE Trial. British Medical Journal. 2004;328:134–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37942.601331.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall DB, Sevrini TA. Extended generalized estimating equations for clustered data. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1998;93(444):1365–75. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basu A, Rathouz PJ. Estimating marginal and incremental effects on health outcomes using flexible link and variance function models. Biostatistics. 2005 Jan;6(1):93–109. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxh020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huber PJ. Robust statistics: A review. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1972;43:1041–67. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Hagan A, Foster J. Kendall’s Advanced Theory of Statistics: Bayesian Inference. 2. London: Edward Arnold; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Hagan A, Luce BR. A Primer on Bayesian Statistics in Health Economics and Outcomes Research. Bethesda, Maryland: MEDTAP International Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spiegelhalter DJ, Thomas A, Best N, Lunn D. WinBUGS User Manual. Cambridge, UK: MRC Biostatistics Unit; 2003. Version 1.4 ed. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilks WR, Richardson S, Spiegelhalter DJ. Markov Chain Monte Carlo in practice. London: Chapman and Hall; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gelman A, Hill J. Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. 1. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oaxaca R. Male-female Wage Differentials in Urban Labor Markets. International Economic Review. 1973;14(3):693–709. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson J, Palmer T, Moreno S. Bayesian analysis in Stata with WinBUGS. The Stata Journal. 2006;6(4):530–49. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pregibon D. Goodness of link tests for generalized linear models. Applied Statistics. 1980;29:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramsey JB. Tests for specification error in classical linear least squares regression analysis. Journal of Royal Statistical Society-Series B. 1969;31:350–71. [Google Scholar]