Abstract

Introduction

Addressing maternal smoking and child secondhand smoke exposure is a public health priority. Standard care advice and self-help materials to help parents reduce child secondhand smoke exposure is not sufficient to promote change in underserved populations. We tested the efficacy of a behavioral counseling approach with underserved maternal smokers to reduce infant’s and preschooler’s secondhand smoke exposure.

Design

A two-arm randomized trial: experimental behavior counseling versus enhanced standard care (control). Assessment staff members were blinded.

Setting/participants

Three hundred randomized maternal smokers were recruited from low-income urban communities. Participants had a child aged <4 years exposed to two or more maternal cigarettes/day at baseline.

Intervention

Philadelphia Family Rules for Establishing Smokefree Homes (FRESH) included 16 weeks of counseling. Using a behavioral shaping approach within an individualized cognitive–behavioral therapy framework, counseling reinforced efforts to adopt increasingly challenging secondhand smoke exposure–protective behaviors with the eventual goal of establishing a smokefree home.

Main outcome measures

Primary outcomes were end-of-treatment child cotinine and reported secondhand smoke exposure (maternal cigarettes/day exposed). Secondary outcomes were end-of-treatment 7-day point-prevalence self-reported cigarettes smoked/day and bioverified quit status.

Results

Participation in FRESH behavioral counseling was associated with lower child cotinine (β= −0.18, p=0.03) and secondhand smoke exposure (β= −0.57, p=0.03) at end of treatment. Mothers in behavioral counseling smoked fewer cigarettes/day (β= –1.84, p=0.03) and had higher bioverified quit rates compared with controls (13.8% vs 1.9%, χ2=10.56, p<0.01). There was no moderating effect of other smokers living at home.

Conclusions

FRESH behavioral counseling reduces child secondhand smoke exposure and promotes smoking quit rates in a highly distressed and vulnerable population.

Introduction

Children’s secondhand smoke exposure (SHSe) is a leading preventable cause of pediatric morbidity and mortality.1,2 SHSe is causally related to a wide range of pediatric health problems, including sudden infant death syndrome, asthma, middle ear disease, pneumonia, and bronchitis, and is associated with behavioral disorders in preschoolers as well as elevated cardiovascular and cancer risk.2–17 More than 40% of children are exposed to SHS daily.4,18,19 The highest SHSe rates are observed in low-income, minority, and medically underserved communities,19–26 and younger children bear increased vulnerability to SHSe.27–30 Because maternal smoking is the primary source of infant and preschoolers’ SHSe,9,27,30 addressing maternal smoking in underserved populations remains a public health priority.31–34

Poverty relates to higher smoking rates among women of childbearing age,35,36 as well as greater smoking- and SHSe-related disease burden.4,31,37 Impoverished women are also less likely to quit smoking than those in higher socioeconomic groups.35,36,38 Public policies and pediatric clinic-level interventions39–41 to address these disparities have fallen short42,43; alone, these approaches are not sufficient to promote cessation or SHSe reduction in underserved groups of smokers that experience numerous barriers to health behavior change.40,44–48 More-intensive smoking interventions are necessary to help parents in underserved populations overcome barriers to child SHSe reduction.4,35,38,45,49–53 A recent meta-analysis54 and systematic reviews46,50 suggest that behavioral counseling (BC) to reduce residential child SHSe shows greater potential for impact than existing public policies, standard care brief advice, health education, and self-help materials. However, smokers from underserved populations are less likely to uptake intensive evidence-based counseling interventions55,56 and few BC programs address the specific challenges of underserved maternal smokers. Therefore, an opportunity exists to design and test intensive evidence-based interventions that are both acceptable and efficacious in this vulnerable population.

The purpose of this trial was to test the efficacy of a moderately intensive behavioral health promotion approach to SHSe reduction among underserved maternal smokers with SHS-exposed infants and preschoolers. Philadelphia Family Rules for Establishing Smokefree Homes (FRESH) used a combination of evidence-based, BC strategies (e.g.,57,58) with innovative emphases on child well-being and behavioral shaping methods. Shaping focuses initially on attainable, short-term SHSe-reduction goals (e.g., making children’s bedrooms smokefree). Counselors highlight and praise short-term efforts and accomplishments to motivate further goal setting and efforts toward more ambitious smoking behavior change (e.g., total home smoking ban). Such an approach capitalizes on parents’ receptivity to protect their children from SHSe59 and attempts to build confidence and maintain engagement in the smoking behavior change process. Thus, although the primary intervention focus and study outcome in FRESH was child SHSe reduction, treatment could also promote smoking cessation (an exploratory, secondary study outcome). Therefore, we hypothesized that: (1) children of mothers receiving FRESH BC would have lower post-intervention SHSe than children in a standard care control group whose mothers received brief advice and detailed self-help materials that paralleled BC content; and (2) that other residential smokers would attenuate counseling effects. This moderation analysis is important for determining the degree to which competing social contingencies among smokers in the home may affect child SHSe and maternal smoking.

Methods

Philadelphia FRESH was an RCT aimed to help underserved maternal smokers reduce infant and preschoolers’ SHSe. Participants were recruited from low-income neighborhoods in North and West Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After providing informed consent, participants completed a 45-minute in-home baseline interview and collected their child’s urine for cotinine assays. Participants were randomized to receive either: (1) FRESH BC delivered by master’s degree– level counselors (e.g., MA, MSW, MPH); or (2) an enhanced self-help control (SHC) intervention (no counseling). After a 16-week intervention period, participants completed an in-home, end-of-treatment (EOT) interview, collected child urine for cotinine assessment, and provided saliva to verify quit status. Data collection interviewers were blinded to treatment status. Interviewers and counselors received extensive training and attended separate weekly meetings for supervision and fidelity monitoring feedback from audiotaped assessment interviews and counseling sessions. Data collection and analyses were conducted from 2006 to 2013. All procedures were approved by Temple University’s IRB.

Study Sample

Eligible participants included light-to-moderate (five or more cigarettes/day) smoking mothers with a child aged <4 years who were exposed in the same room (four walls with a door) or car to two or more maternal cigarettes/day. Exclusion criteria were diagnosis or treatment for severe mental illness, pregnancy, and English as a secondary language.

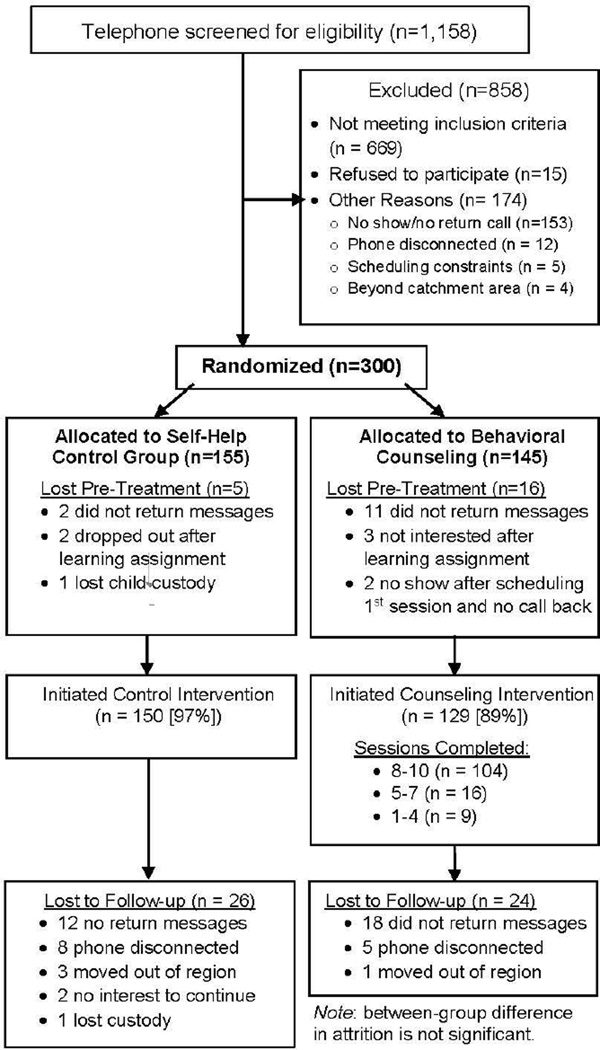

The project employed purposive sampling with recruitment and retention efforts described in detail elsewhere.60 Participants were recruited both actively from pediatric primary care and community clinics providing the Special Supplementary Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) as well as passively with advertisements in free community newspapers, on mass transit serving low-income neighborhoods, and on fliers in local stores. Participants were randomized with block randomization using small blocks of random length, stratified by child race, gender, and recruitment site (WIC, pediatrics, or advertisements). After baseline completion, the intervention manager obtained group assignment via a secured Internet interface. Figure 1 displays participant flow.

Figure 1.

Participant flow through procedures.

Interventions

Both intervention groups received evidence-based strategies that included health education about SHSe dangers, benefits of SHSe protection/reduction and a smokefree lifestyle, information about nicotine replacement and medications, as well as guidance for establishing a smokefree home, identifying triggers/cues for smoking, managing smoking urges, parenting stress, moods and weight concerns, and building support for smoking behavior change. Both groups received information about local cessation services and nicotine-replacement therapy (NRT) products (e.g., nicotine gum) available at low or no cost to low-income smokers.

Participants randomized to receive FRESH behavioral counseling were scheduled to complete two in-home and seven telephone sessions within 16 weeks. Home sessions were completed in the first 5 weeks and aimed to introduce key intervention elements. To enhance intervention tailoring to individuals, counselors identified contextual factors that functioned either as facilitators of or barriers to behavior change. During home sessions, counselors offered skills training and modeled support for SHSe-reduction efforts. Their advice emphasized how to: (1) establish and monitor short-term goals; (2) negotiate and develop family support for SHSe reduction; (3) develop smoking urge management skills; and (4) link SHSe-reduction efforts with preparation for smoking cessation. Phone sessions enabled ongoing support, problem solving and goal monitoring with behavioral shaping, skills training around mood and weight concerns management, and follow-up advice regarding family support for mothers’ SHSe-reduction efforts. Mothers also received four sections of written self-help materials mailed in 2-week intervals after treatment initiation that supplemented counseling content. Counselors encouraged mothers to share these materials, family contracts, worksheets, and goal “prescriptions” with family. Behavioral shaping was utilized within goal monitoring dialog to build confidence and facilitate adoption of more-ambitious goals without pressure for cessation.

Participants randomized to the self-help control intervention were mailed a single binder of written materials within a week of enrollment. The content of the binder was identical to the FRESH BC group’s four separate mailings. During telephone confirmation of receipt, staff provided a 5–10 minute program overview of the binder with brief advice, and encouraged mothers to share materials with family.

Measures

SHSe was measured by child cotinine and maternal self-report. Participants collected their child’s urine sample at baseline and EOT for cotinine assessment. Cotinine provides an accurate, objective means of assessing SHSe from all sources as well as change in SHSe across time points.54,61 Research staff followed standardized collection and storage protocols used effectively in previous studies.62,63 Cotinine assays were performed using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS).64 Cotinine values were log transformed to normalize the distribution.

Reported SHSe from maternal smoking and all sources were collected at baseline and EOT with interviewer-administered, 7-day timeline follow-back (TLFB) methods used in previous studies and demonstrated to be valid, reliable, sensitive, and correlated with child cotinine levels (r =0.50–0.63).65–67

Reported cigarettes smoked per day was collected during baseline and EOT with the aforementioned TLFB assessment methods.

Maternal smoking status at EOT was classified either as quit=1 (successful) or not quit=0 (no quit attempt, or an unsuccessful attempt) based on 7-day TLFB assessment. Quit success was determined by reported smoking abstinence for the 7 consecutive days prior to a follow-up assessment.68 Saliva cotinine was collected from participants and assayed using HPLC-MS to verify reported abstinence (<15 ng/mL).

Control variables included demographic factors, home environment, and theoretically relevant psychosocial factors. Marital status was collected at baseline and dummy coded for analyses as 0=single, 1=married or living with a partner because >80% of the sample was single. Child age was dichotomized for analysis as 0=<12 months and 1=12–48 months to differentiate mothers with older preschoolers from postpartum mothers with infants (potentially more proximal to maternal SHS than older children).

Participant-reported other smokers in home at EOT was dichotomized as 1=other smokers present or 0=mother is the only smoker. Home smoking ban at EOT was derived from a 4-point scale assessing home smoking rules (1=total indoor smoking ban, 4=no smoking restrictions) and dichotomized for analyses as 1=total indoor smoking ban in home and car or 0=no to some smoking restrictions.

Depressive symptoms at baseline were measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).69 Stressful life events at EOT represented the sum of events participants reported experiencing during treatment. This measure was described in a previous study.70 SHSe message dosage at EOT represented the number of non–program related SHS messages about SHSe harms and benefits of SHSe reduction that participants reported receiving from healthcare providers, members of the community, and media sources during treatment71,72 Nicotine dependence at EOT was measured by the Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence.73

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted in Stata, version 12. We generated descriptive statistics and bivariate analyses (e.g., Pearson r, chi-square, or t-test) to examine distributional assumptions and relationships of outcomes, predictors, and covariates. Intent-to-treat methods were employed. Multivariable models for each outcome were estimated using direct entry multiple linear regression. We planned to test the interaction between treatment and other smokers in home at p<0.05 when initial models demonstrated main effects of both variables. Although each of the predictors and outcome variables contained small numbers of missing values, an analysis of complete data only would have reduced our sample by about one third. To retain our sample and avoid the bias arising from missing data, we used multiple imputation methods, which also estimate SEs that incorporate the uncertainty due to imputation.74,75 We used the multiple imputation by chained-equations (MICE) algorithm76 implemented in the STATA language by Royston.77 We first examined the patterns of missingness, then generated series of 40 imputation replicates using the MICE algorithm and Rubin’s75 rules for combining the 40 analyses as implemented in Stata.77 We report a side-by-side comparison of the complete data analysis and multiple imputation analysis.

Results

Figure 1 displays participant flow. As planned, 300 participants were randomized. There were no significant differences in baseline demographics between participants completing the study and those lost to follow-up. There were no significant intervention group differences across baseline demographic characteristics except marital status, with fewer single mothers in the control group. Thus, marital status was included in the multivariable analyses. Table 1 reflects a sample including mostly single, African American, highly distressed mothers. For example, mean CES-D scores (19.46, SD=10.77) were within the significant depressive symptoms range (>16), and almost 90% of mothers reported experiencing two or more concurrent stressful life events.

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics by Group [n (%) or M (SD)]

| Variable |

FRESH Behavioral Counseling (n=145) |

Self-help Control (n=155) |

|---|---|---|

| Marital status (single) | 126 (86.9%) | 118 (76.1%) |

| Mother’s race | Mother’s race | Mother’s race |

| Black | 128 (88.3%) | 134 (86.5%) |

| White | 15 (10.3%) | 20 (12.9%) |

| Other | 2 (1.4%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| Unemployed | 104 (71.7%) | 99 (63.9%) |

| Completed HS education | 83 (57.2%) | 92 (59.4%) |

| Child age | ||

| Mean child age (months) | 19.72 (14.90) | 18.16 (14.05) |

| Children 0–12 months old (vs. older) | 55 (37.9%) | 63 (40.6%) |

| Other smokers in home | 78 (53.8%) | 91 (58.7%) |

| Home smoking ban | ||

| No restrictions | 48 (33.1%) | 51 (32.9%) |

| Some restrictions | 76 (52.4%) | 75 (48.4%) |

| Total indoor ban | 7 (4.83%) | 14 (9.03%) |

| Mother’s cigarettes smoked per day | 12.22 (6.17) | 12.28 (6.44) |

| Reported child SHSe from maternal smoking (cigs/day) |

5.42 (3.79) | 5.32 (4.02) |

| Reported child SHSe from all sources (cigs/day) | 9.29 (10.20) | 8.28 (7.42) |

| Nicotine dependence (FTND) | 4.66 (1.76) | 4.70 (1.87) |

| SHSe message dosage | 2.52 (1.76) | 2.34 (1.98) |

| Stressful Life Events | 9.08 (6.21) | 8.59 (6.00) |

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D) | 19.16 (10.15) | 19.75 (11.35) |

| Log child cotinine | 1.19 (0.49) | 1.26 (0.53) |

HS, high school; SHSe, secondhand smoke exposure; FTND, Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05). All other comparisons were p>0.05.

Participants randomized to FRESH BC could complete up to ten sessions (two home visits, seven phone sessions, and one quit day phone session if mother set a quit day). Overall, participants completed a mean of 7.93 (SD=3.11) sessions. One hundred four (71.7%) completed eight to ten sessions, 11% completed five to seven sessions, 6.3% completed two to four sessions, and 11% completed only one session. Mean contact time was 2.72 (SD=1.43) hours of counseling. Twelve (8.3%) participants reported obtaining additional self-help materials, 1.4% used withdrawal medications, and 2.8% reported NRT use in the 7 days prior to EOT assessment. Among SHC participants, 100% reported receiving their self-help binder, 0% used medications, 1.9% used NRT, and 9.0% reported using smoking-cessation services.

Comparison of intent-to-treat and complete case data analyses demonstrated moderate inflation of SEs by the multiple imputation procedures, but only small differences in the coefficient estimates. These comparisons suggest reliability of imputation methods and robustness of the relationships.

Intent-to-treat and complete case multivariable regression analyses generated similar, significant models accounting for approximately 28% of the variance in child urine cotinine at EOT (Table 2). FRESH BC was associated with lower cotinine compared with SHC group participation (β= −0.18, p=0.03, d=0.32). There was no significant association between other smokers in the home and cotinine (β=0.114, p=0.134). A residential smoking ban and fewer reported stressful life events were associated with lower cotinine compared with no ban and more life events endorsed. Because there was no effect of other smokers, we did not test for moderation.

Table 2.

Main Effect of Treatment on Child Secondhand Smoke Exposure

| Child cotinine | ||

|---|---|---|

| Complete data only (N=198) F(10, 187)=7.09, p<.001. R2=.28 |

Multiple imputation (N=300) F(10, 261.8)=5.84, p<.001 |

|

| Predictor | Coefficient (CI 95%) | Coefficient (CI 95%) |

| Treatment | −0.177 (−0.333 to −0.022)* | −0.183 (−0.346 to −0.021)* |

| Other smokers in home | 0.102 (−0.049 to 0.252) | 0.114 (−0.035 to 0.263) |

| Nicotine dependence | −0.023 (−0.060 to 0.015) | −0.024 (−0.059 to 0.011) |

| Home smoking ban | −0.283 (−0.455 to −0.110)** | −0.293 (−0.471 to −0.114)** |

| Stressful life events | 0.019 (0.006 to 0.033)** | 0.018 (0.005 to 0.031)** |

| SHSe message dosage | 0.016 (−0.021 to 0.053) | 0.017 (−0.020 to 0.053) |

| Child age | 0.132 (−0.023 to 0.288) | 0.101 (−0.054 to 0.255) |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.005 (−0.012 to 0.003) | −0.005 (−0.123 to 0.002) |

| Marital status | −0.001 (−0.193 to 0.191) | 0.020 (−0.172 to 0.211) |

| Log cotinine baseline | 0.419 (0.270 to 0.567)*** | 0.365 (0.221 to 0.510)*** |

| Reported child SHSe from maternal smoking (cigarettes/day). | ||

|---|---|---|

| Complete data only (N=226) F(10, 215)=12.45, p<.001. R2=.367 |

Multiple imputation (N=300) F(10, 277.18)=14.09, p<.001. |

|

| Predictor | Coefficient (CI 95%) | Coefficient (CI 95%) |

| Treatment | −0.585 (−1.136 to −0.034)* | −0.565 (−1.084 to −0.045)* |

| Other smokers in home | −0.543 (−1.080 to 0.008)* | −0.522 (−1.019 to −0.024)* |

| Nicotine dependence | 0.375 (0.246 to 0.510)** | 0.356 (0.226 to 0.487)** |

| Home smoking ban | −1.31 (−1.923 to −0.691)** | −1.579 (−2.183 to −0.974)*** |

| Stressful life events | 0.022 (−0.026 to 0.068) | 0.017 (−0.030 to 0.064) |

| SHSe message dosage | −0.023 (−0.155 to 0.109) | −0.028 (−0.157 to 0.101) |

| Child age | 0.070 (−0.471 to 0.610) | 0.129 (−0.367 to 0.625) |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.011 (−0.014 to 0.036) | 0.007 (−0.015 to 0.030) |

| Marital status | 0.610 (−0.075 to 1.293) | 0.601 (−0.046 to 1.248) |

| Cigs exposed at baseline | 0.116 (0.051 to 0.181)*** | 0.115 (0.052 to 0.179)*** |

Note: p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

Intent-to-treat and complete case multivariable regression analyses resulted in similar, significant models accounting for approximately 50% of the variance in reported SHSe to maternal cigarettes (Table 2). FRESH BC participation (β= −0.57, p=0.03, d=0.24) and residential smoking bans were associated with lower SHSe compared with SHC and no ban. There was a significant effect of other smokers in the home (β= −0.52, p=0.04, d=0.22), such that other smokers at home related to lower SHSe to maternal cigarettes at EOT compared with having no other smokers at home. Also, greater nicotine dependence related to higher reported SHSe to maternal cigarettes. Moderation analysis failed to yield a significant interaction, although a significant treatment effect remained in the model.

SHSe from all sources both inside and away from home significantly correlated with child cotinine (r =0.16, p=0.01). Complete case and intent-to-treat analyses resulted in similar, significant models accounting for approximately 37% of the variance in all-source SHSe. There was not a significant treatment effect; however, there was a trend related to other smokers in the home (β=1.930, p=0.057, d=0.27) such that mothers living with other smokers reported higher SHSe from all sources compared to mothers who were the only smokers at home. Lower nicotine dependence (β=0.666, p=0.006) was also related to lower all-source SHSe.

Similar complete case and intent-to-treat results suggested a significant model that accounted for approximately 50% of the variance in self-reported cigarettes smoked per day at EOT. Table 3 illustrates that participation in FRESH BC compared with SHC was associated with fewer cigarettes smoked per day (β= −1.837, p=0.033, d=032). There was no effect of other smokers. Lower nicotine dependence and fewer reported stressful life events were associated with fewer cigarettes smoked per day. Because other smokers were not a significant factor in the model, we did not conduct moderation analysis.

Table 3.

Main Effect of Treatment on Mother’s Cigarettes Smoked Per Day

| Complete data only (N=226) F(10, 215)=23.74, p<.001. R2=.503 |

Multiple imputation (N=300) F(10, 277.18)=22.59, p<.001. |

|

|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Coefficient (CI 95%) | Coefficient (CI 95%) |

| Treatment | −1.695 (−2.850 to −0.540)** | −1.837 (−3.006 to −0.669)* |

| Other smokers in home | −0.057 (−1.182 to 1.068) | −0.083 (−1.052 to 1.218) |

| Nicotine dependence | 1.439 (1.171 to 1.708)*** | 1.398 (1.116 to 1.680)*** |

| Home smoking ban | −0.596 (−1.890 to 0.699) | −0.898 (−2.218 to 0.422) |

| Stressful life events | 0.141 (0.042 to 0.240)** | 0.131 (0.032 to 0.230)* |

| SHSe message dosage | −0.039 (−0.315 to 0.237) | −0.061 (−0.363 to 0.242) |

| Child age | 0.107 (−1.028 to 1.242) | 0.180 (−0.940 to 1.301) |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.020 (−0.033 to 0.072) | 0.017 (−0.036 to 0.070) |

| Marital status | −0.887 (−0.545 to 2.319) | 0.894 (−0.584 to 2.373) |

| Cigs smoked at baseline | 0.217 (0.133 to 0.302)*** | 0.228 (0.144 to 0.311)** |

Note: p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

In the FRESH BC condition, 28 (19.3%) participants reported quitting smoking at EOT compared with five (3.2%) in the SHC condition (χ2=19.99, p<0.001, d=0.53). Twenty (13.8%) of the BC participants had bioverified quit status compared with three (1.9%) in the control group (χ2=10.56, p<0.01, d=0.38). Participants with missing cotinine data were classified as still smoking (not quit) at EOT.

Discussion

Compared with standard care with self-help materials (SHC), FRESH BC promoted lower self-reported SHSe to maternal cigarettes, cigarettes smoked per day, and child cotinine when statistically controlling for other factors known to influence maternal smoking. Our effect sizes are consistent with other interventions.54 Importantly, this study has demonstrated potential efficacy of FRESH BC in a high-risk, highly distressed sample of maternal smokers known to have greater challenges with smoking behavior change.

The moderation hypothesis was not supported. Interestingly, the reported SHSe data suggest that the presence of other smokers in the home facilitated the reduction of maternal SHS. We had expected that the presence of other smokers and their contribution to SHS and thirdhand smoke exposure in the home would undermine FRESH treatment effects and adversely effect cotinine outcomes. On the contrary, the FRESH approach may mitigate a key factor (other smokers at home) known to undermine smokers’ behavior change efforts. Perhaps these results highlight the importance of written materials and counselors’ coaching and follow-up with mothers around: (1) their discussions with family members about the importance of SHSe-protective behaviors; (2) developing positive family social support for mothers’ efforts; and (3) including family members in behavioral contracting and goal setting processes. These treatment strategies could help address and modify social contingencies that facilitate, rather than hinder, family-level support and behavior change. Other research reflects awareness of the importance of family involvement in the SHSe-reduction process.78,79

Our BC approach did not influence reported SHSe from all sources in all locations. Only lower nicotine dependence and absence of other smokers at home predicted lower all-source SHSe. Perhaps compared with less-dependent smokers, more-dependent maternal smokers are less resilient to confront pro-smoking social pressure, thereby limiting their ability to confront other smokers. Multilevel interventions blending community-level policies that foster social norms for SHSe protection with BC may be necessary to influence change in non-residential sources of SHS.40

It appears that FRESH BC facilitates short-term smoking cessation with results comparable to other SHSe-reduction trials (e.g.,80) and smoking-cessation interventions in similar populations.81 These quit rates are encouraging for two reasons. First, less than 3% of FRESH mothers used either NRT or cessation medications (consistent with evidence of low uptake of medications and NRT in underserved populations).55,56 Second, although cotinine remains the gold standard for verification of quit status (to reduce potential biases related to self-reported abstinence), our verified cessation results may actually underestimate mothers’ efforts to quit smoking (e.g., their cotinine could be elevated because of their exposure to other smokers’ SHS.)54 Future studies could consider functional analysis of the relative utility of adding NRT and cessation medications to SHSe counseling for maternal smokers. However, we caution that future behavioral health interventions for child SHSe reduction in underserved populations not focus exclusively on smoking cessation as opposed to shaping parents’ SHSe-protective behaviors in contexts where children are most likely exposed. Although cessation is the ideal long-term goal for maternal smokers, few can achieve and maintain cessation, whereas SHSe-protective behaviors are more easily adopted and maintained.

Limitations

Our results should be interpreted knowing the study limitations. For example, we chose to reduce assessment burden by excluding objective measures of child health, smoking outcomes of other smokers, and level of family involvement. Future studies designed to assess the effects of SHSe counseling interventions on objective child health outcomes (e.g., asthma) could bolster advocacy and funding for implementing interventions such as FRESH within the Affordable Care Act. Currently in medical practice, behavioral health interventions are stripped of necessary intensity in favor of brief (but ineffective) interventions. Also, understanding more about family involvement in the process could improve understanding of social prompts and reinforcing consequences that either support smoking behavior change or maintain current SHSe behaviors. Another study limitation: owing to limited resources, we did not measure household nicotine, thirdhand smoke,27,82 or specific sources of SHSe outside the home (e.g., multiunit dwellings, public spaces). Follow-up studies that assess the degree to which exposure to thirdhand smoke and nonresidential SHS changes as a function of behavioral health intervention, such as FRESH, could guide future interventions and policy. Our study did not track pediatric providers’ and WIC counselors’ SHSe advice. Such data could guide the development of multilevel approaches that capitalize on the influence and credibility of provider advice while offering the level of intervention intensity necessary to promote smoking behavior change in underserved populations. Multilevel interventions could maximize potential synergistic effects across interacting clinic and family levels of social contingencies that influence SHSe.40,83 Finally, we did not include a follow-up assessment. However, we argue that exploring whether smoking treatment effects are maintained once withdrawn (e.g., via follow-up assessment) is superfluous to determining potential impact of an intervention like FRESH. Clinicians should not arbitrarily withdraw effective behavioral treatment for maternal smoking and child SHSe reduction considering: (1) the severity of smoking and SHSe-related consequences; (2) the enormous challenges underserved maternal smokers face in changing smoking behavior; and (3) the chronic relapsing nature of nicotine dependence. On the contrary, and as best practices guidelines (“Ask, Advise, Refer”) suggest, evidence-based advice and counseling should always be available and encouraged. To empirically test questions about the maintenance of treatment effects in future work, behavioral scientists could test strategies to enhance sociocultural contingencies supporting sustained SHSe reduction or cessation before withdrawing clinical support.

Our study has many strengths. Our moderate-intensity BC model was feasible and acceptable in a public health priority population known to suffer elevated tobacco-related morbidity/mortality risks and bear greater challenges to health behavior change relative to the general population. Our behavioral health approach used an innovative combination of evidence-based counseling strategies within a behavioral shaping paradigm to promote child SHSe reduction. Although the intensity of FRESH may exceed what is necessary in the general population of parental smokers, our intervention contained program elements with an acceptable level of intensity necessary to promote SHSe reduction in this high-risk population.

Cost analyses were beyond the scope of this study. Future studies could replicate the FRESH approach, examine mechanisms of maternal smoking behavior change affected by FRESH, and test our strategy for optimal implementation and dissemination. If effects of FRESH are replicated, researchers could either conduct dismantling research to determine the most cost-effective number of sessions, or complete a comparative effectiveness analysis study to test the relative utility of the two home visits (followed by phone sessions) as opposed to a more cost effective, entirely telebased version of FRESH. A fully telebased version could be implemented via state quitlines, an emerging standard referral option in pediatrics. In its current format, the FRESH model promotes maternal and child health and fosters behavior change necessary to alter biological risk markers in mothers and children. Therefore, this behavioral health approach to disease prevention is appropriate for, and could be supported by, the Affordable Care Act.84 Medical care providers are not equipped to either deliver the necessary intensity of behavioral health intervention to promote SHSe reduction, or provide in-home services. However, our intervention structure is similar to other emerging community health models85,86 and could be implemented with behavioral health counselors. Such an approach could create large public health impact by providing an accessible, acceptable, and efficacious BC intervention in communities that have the highest smoking- and SHSe-related health burdens.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results suggest the potential efficacy of the FRESH behavioral health approach to reducing child SHSe in a vulnerable, high-risk population of smokers. The presence of other smokers in the home does not undermine maternal smokers’ efforts to reduce either their daily smoking or child’s exposure to their cigarettes; in fact, our counseling model may engage them to support mothers’ efforts in the intervention process. Our model may have limits in its capacity to facilitate reduction of SHSe in locations outside of home. However, its ability to potentially modify family-level behavior and facilitate smoking cessation in the absence of NRT or withdrawal medications suggests large potential for public health impact. Moreover, the FRESH model could be merged with existing community-based medical or behavioral health agencies (as we are testing in pediatric primary care40 and another group is testing in an urban Head Start program).87 Such programs can target high-risk populations, offering a cost-effective approach to establish and reinforce skills,88 and maintain motivation during the complex smoking behavior change process.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute at the NIH to B. Collins (CA105183 and CA93756). The authors thank the following staff and colleagues who contributed to the project: Linda Kilby, PhD, Jamie Dahm, MS, James Kingham, MS, Lauren Rider, MS, Darryl Meuller, MD, MPH, and Dawit Nehemia, BA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.U.S. DHHS. Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. DHHS CDC Coord Cent Heal Promot Natl Cent Chronic Dis Prev Heal Promot; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. DHHS. How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: 2010. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53017/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer NS, Anand V, Carroll AE, Downs SM. Secondhand Smoke Exposure, Parental Depressive Symptoms and Preschool Behavioral Outcomes. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(1):227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2014.06.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. DHHS. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: A report of the surgeon general. CDC; 2006. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44324/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.California Environmental Protection Agency. Health effects of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Final draft for scientific, public and SRP review. Tob Control. 1997;6(4):346–353. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.4.346. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tc.6.4.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson HR, Cook DG. Passive smoking and sudden infant death syndrome: review of the epidemiological evidence. Thorax. 1997;52(11):1003–1009. doi: 10.1136/thx.52.11.1003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.52.11.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gergen PJ, Fowler JA, Maurer KR, Davis WW, Overpeck MD. The burden of environmental tobacco smoke exposure on the respiratory health of children 2 months through 5 years of age in the United States: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988 to 1994. Pediatrics. 1998;101(2):E8. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.2.e8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.101.2.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blizzard L, Ponsonby A-L, Dwyer T, Venn A, Cochrane JA. Parental smoking and infant respiratory infection: how important is not smoking in the same room with the baby? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(3):482–488. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.3.482. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.3.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dwyer T, Ponsonby AL, Couper D. Tobacco smoke exposure at one month of age and subsequent risk of SIDS--a prospective study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(7):593–602. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009857. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. DHHS. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: 2004. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44324/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becklake MR, Ghezzo H, Ernst P. Childhood predictors of smoking in adolescence: a follow-up study of Montreal schoolchildren. CMAJ. 2005;173:377–379. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041428. http://dx.doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1041428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belanger M, O’Loughlin J, Okoli CTC, et al. Nicotine dependence symptoms among young never-smokers exposed to secondhand tobacco smoke. Addict Behav. 2008;33(12):1557–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Treyster Z, Gitterman B. Second hand smoke exposure in children: Environmental factors, physiological effects, and interventions within pediatrics. Rev Environ Health. 2011;26(3):187–195. doi: 10.1515/reveh.2011.026. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/reveh.2011.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burke H, Lornardi-Bee J, Hashim A, et al. Prenatal and passive smoke exposure and incidence of asthma and wheeze: systematic review and meta analysis. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):735–744. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell EA, Milerad J. Smoking and the sudden infant death syndrome. Rev Environ Health. 2006;21(2):81–103. doi: 10.1515/reveh.2006.21.2.81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/REVEH.2006.21.2.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones LL, Hassanien A, Cook DG, Britton J, Leonardi-Bee J. Parental smoking and the risk of middle ear disease in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(1):18–27. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.158. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones LL, Hashim A, McKeever T, Cook DG, Britton J, Leonardi-Bee J. Parental and household smoking and the increased risk of bronchitis, bronchiolitis and other lower respiratory infections in infancy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2011;12:5. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-12-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO. Tobacco Fact Sheet. 2014 www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/

- 19.Kum-Nji P, Meloy L, Herrod HG. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure: prevalence and mechanisms of causation of infections in children. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1745–1754. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1886. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, Fidler JA, Munafò M. Socioeconomic status and smoking: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1248:107–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06202.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CDC. Cigarette smoking among adults and trends in smoking cessation. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(44):1227–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Martinez-Donate AP, Kuo D, Jones NR, Palmersheim KA. Trends in home smoking bans in the U.S.A., 1995–2007: prevalence, discrepancies and disparities. Tob Control. 2012;21(3):330–336. doi: 10.1136/tc.2011.043802. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tc.2011.043802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muscat JE, Djordjevic MV, Colosimo S, Stellman SD, Richie JP. Racial differences in exposure and glucuronidation of the tobacco-specific carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) Cancer. 2005;103(7):1420–1426. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20953. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pew Charitable Trusts. Philadephia 2009: The state of the city. 2009 www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2009/03/30/philadelphia-2009-the-state-of-the-city.

- 25.Tsourtos G, O’Dwyer L. Stress, stress management, smoking prevalence and quit rates in a disadvantaged area: has anything changed? Health Promot J Austr. 2008;19(1):40–44. doi: 10.1071/he08040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CDC. Secondhand smoke (SHS) fact sheets. 2013;27 SRC -. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/secondhand_smoke/general_facts/index.htm#disparities. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matt GE, Quintana PJE, Hovell MF, et al. Households contaminated by environmental tobacco smoke: sources of infant exposures. Tob Control. 2004;13(1):29–37. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.003889. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tc.2003.003889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tyc VL, Hovell MF, Winickoff J. Reducing secondhand smoke exposure among children and adolescents: emerging issues for intervening with medically at-risk youth. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33(2):145–155. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsm135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klerman L. Protecting children: reducing their environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(Suppl 2):S239–S253. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669213. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14622200410001669213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stiby AI, Macleod J, Hickman M, Yip VL, Timpson NJ, Munafò MR. Association of maternal smoking with child cotinine levels. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(12):2029–2036. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt094. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntt094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.CDC. Women and Smoking: A Report from the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. DHHS. Maternal, infant, and child health. 2020 topics and objectives. 2014 http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=26.

- 33.WHO. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2009: implementing smoke-free environments. 2009 www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/2009/en/index.html.

- 34.WHO. Tobacco Fact Sheet. 2014 www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/

- 35.Tong VT, Jones JR, Dietz PM, D’Angelo D, Bombard JM CDC. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy - Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), United States, 31 sites, 2000–2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58(4):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kahn RS, Certain L, Whitaker RC. A reexamination of smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(11):1801–1808. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1801. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.92.11.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collins BN, Nair US, Spiers M, Gellar P, Kloss J. Women and smoking. In: Spiers M, Gellar P, Kloss J, editors. Womens health psychology. Vol. 2013. SRC. NY: Wiley; 2013. pp. 123–148. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melvin C, Gaffney C. Treating nicotine use and dependence of pregnant and parenting smokers: an update. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(Suppl 2):S107–S124. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669231. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14622200410001669231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. DHHS. Clinical Practice Guideline. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. 2008 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63952/

- 40.Lepore SJ, Winickoff JP, Moughan B, et al. Kids Safe and Smokefree (KiSS): a randomized controlled trial of a multilevel intervention to reduce secondhand tobacco smoke exposure in children. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:792. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-792. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winickoff JP, Park ER, Hipple BJ, et al. Clinical effort against secondhand smoke exposure: development of framework and intervention. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):e363–e375. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0478. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-0478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collins BN, Levin KP, Bryant-Stephens T. Pediatricians’ practices and attitudes about environmental tobacco smoke and parental smoking. J Pediatr. 2007;150(5):547–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.01.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mueller D, Collins BN. Pediatric otolayngologists’ actions regarding secondhand smoke exposure: Pilot data suggest an opportunity to enhance tobacco intervention. Otolary HN Surg. 2008;139(3):348–352. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.05.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collins BN, Ibrahim JK, Hovell M, et al. Residential smoking restrictions are not associated with reduced child SHS exposure in a baseline sample of low-income, urban African Americans. Health (Irvine Calif) 2010;2(11):1264–1271. doi: 10.4236/health.2010.211188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collins B, Ibrahim J. Pediatric Secondhand Smoke Exposure: Moving Toward Systematic Multi-Level Strategies to Improve Health. Glob Heart. 2012;7(2):161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2012.05.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gheart.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Priest N, Roseby R, Waters E, et al. Family and carer smoking control programmes for reducing children’s exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD001746. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001746.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.NIH Science of Behavior Change - Meeting Report. 2009:1–39. http://commonfund.nih.gov/behaviorchange/meetings/sobc061509/index.

- 48.Moore GF, Holliday JC, Moore LAR. Socioeconomic patterning in changes in child exposure to secondhand smoke after implementation of smoke-free legislation in Wales. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(10):903–910. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr093. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Max W, Sung H-Y, Shi Y. Who is exposed to secondhand smoke? Self-reported and serum cotinine measured exposure in the U.S., 1999–2006. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6(5):1633–1648. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6051633. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph6051633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh GK, Siahpush M, Kogan MD. Disparities in children’s exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in the United States, 2007. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):4–13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2744. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reus VI, Smith BJ. Multimodal techniques for smoking cessation: a review of their efficacy and utilisation and clinical practice guidelines. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(11):1753–1768. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01885.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hovell MF, Hughes SC. The behavioral ecology of secondhand smoke exposure: A pathway to complete tobacco control. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(11):1254–1264. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp133. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntp133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.NIH. Science of behavior change. Vol. 2009. SRC. Bethesda, MD: 2009. pp. 1–39. http://commonfund.nih.gov/behaviorchange/meetings/sobc061509/index. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosen LJ, Myers V, Hovell M, Zucker D, Ben Noach M. Meta-analysis of Parental Protection of Children From Tobacco Smoke Exposure. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):698–714. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0958. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cokkinides VE, Ward E, Jemal A, Thun MJ. Under-use of smoking-cessation treatments: results from the National Health Interview Survey, 2000. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(1):119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fu SS, Kodl MM, Joseph AM, et al. Racial/Ethnic disparities in the use of nicotine replacement therapy and quit ratios in lifetime smokers ages 25 to 44 years. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(7):1640–1647. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2726. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Emmons KM, Hammond SK, Fava JL, Velicer WF, Evans JL, Monroe AD. A randomized trial to reduce passive smoke exposure in low-income households with young children. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):18–24. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hovell MF, Meltzer SB, Wahlgren DR, et al. Asthma management and environmental tobacco smoke exposure reduction in Latino children: a controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2002;110(5):946–956. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.5.946. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.110.5.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mahabee-Gittens EM, Collins BN, Murphey SA, et al. The parent-child dyad and risk perceptions among parents who quit smoking. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(5):596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Collins BN, Wileyto EP, Hovell MF, et al. Proactive recruitment predicts participant retention to end of treatment in a secondhand smoke reduction trial with low-income maternal smokers. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(3):394–399. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0059-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13142-011-0059-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Benowitz NL. Cotinine as a biomarker of environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Epidemiol Rev. 1996;18(2):188–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017925. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hovell MF, Zakarian JM, Wahlgren DR, Matt GE, Emmons KM. Reported measures of environmental tobacco exposure: trials and tribulations. Tob Control. 2000;9(Suppl 3):22–28. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_3.iii22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tc.9.suppl_3.iii22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Niedbala RS, Haley N, Kardos S, Kardos K. Automated homogeneous immunoassay analysis of cotinine in urine. J Anal Toxicol. 2002;26(3):166–170. doi: 10.1093/jat/26.3.166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jat/26.3.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bernert JT, McGuffey JE, Morrison MA, Pirkle JL. Comparison of serum and salivary cotinine measurements by a sensitive high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method as an indicator of exposure to tobacco smoke among smokers and nonsmokers. J Anal Toxicol. 2000;24(5):333–339. doi: 10.1093/jat/24.5.333. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jat/24.5.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matt GE, Hovell MF, Zakarian JM, Bernert JT, Pirkle JL, Hammond SK. Measuring secondhand smoke exposure in babies: the reliability and validity of mother reports in a sample of low-income families. Health Psychol. 2000;19(3):232–241. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.3.232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.3.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hovell MF, Zakarian JM, Matt GE, et al. Counseling to reduce children’s secondhand smoke exposure and help parents quit smoking: A controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(12):1383–1394. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp148. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntp148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matt GE, Wahlgren DR, Hovell MF, et al. Measuring environmental tobacco smoke exposure in infants and young children through urine cotinine and memory-based parental reports: empirical findings and discussion. Tob Control. 1999;8(3):282–289. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.3.282. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tc.8.3.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(1):13–25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/5.1.13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Radloff LS. A CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Collins B, Nair U, Shwarz M, Jaffe K, Winickoff J. SHS-Related Pediatric Sick Visits are Linked to Maternal Depressive Symptoms Among Low-Income African American Smokers: Opportunity for Intervention in Pediatrics. J Child Fam Stud. 22(7) doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9663-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nair U, Collins B, Kwakye N, Ibrahim J, Jaffe K. Secondhand smoke messages: Dosage and different sources’ influence on postpartum smoking and baby exposure; Annual meeting of the American Public Health Association; Philadelphia, PA. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jaffe Tolley NM, Ibrahim J, Collins BNK. Health systems and policy implications related to dosage of advice about SHS reduction. Annu Int Conf Commun Med Ethics. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shafer JL. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall; 1997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1201/9781439821862. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1987. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470316696. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Van Buuren SHC, Knook DL. Multiple imputation of missing blood pressure covariates in survival analysis. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):681–694. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<681::aid-sim71>3.0.co;2-r. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<681::AID-SIM71>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: Update. Stata J. 2005;5(2):188–201. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stotts AL, Northrup TF, Schmitz JM, et al. Baby’s Breath II protocol development and design: A secondhand smoke exposure prevention program targeting infants discharged from a neonatal intensive care unit. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35(1):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.02.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kegler MC, Escoffery C, Bundy L, et al. Pilot study results from a brief intervention to create smokefree homes. J Environ Public Health. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/951426. Article ID 951426. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/951426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Hovell MF, Zakarian JM, Matt GE, et al. Counseling to reduce children’s secondhand smoke exposure and help parents quit smoking: a controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(12):1383–1394. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp148. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntp148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rosen LJ, Ben Noach M, Winickoff JP, Hovell MF. Parental smoking cessation to protect young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):141–152. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Matt GE. Thirdhand Tobacco Smoke: Emerging Evidence and Arguments for a Multidisciplinary Research Agenda. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;119(9):1218–1226. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103500. http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1103500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hovell MF, Hughes SC. The behavioral ecology of secondhand smoke exposure: A pathway to complete tobacco control. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(11):1254–1264. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp133. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntp133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Federal Register. 2013 www.hhs.gov/healthcare/rights/

- 85.Michalopoulos C, Duggan A, Knox V, et al. Revised Design for the Mother and Infant Home Visiting Program Evaluation: OPRE Report 2013-18. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shah MK, Heisler M, Davis MM. Community Health Workers and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: An Opportunity for a Research, Advocacy, and Policy Agenda. J Healthc Poor Underserved. 2014;25(1):17–24. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2014.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Eakin MN, Rand CS, Borrelli B, Bilderback A, Hovell M, Riekert KA. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing to reduce head start children’s secondhand smoke exposure: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(12):1530–1537. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201404-0618OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201404-0618OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cromwell J, Bartosch WJ, Fiore MC, Hasselblad V, Baker T. Cost-effectiveness of the clinical practice recommendations in the AHCPR guideline for smoking cessation. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. JAMA. 1997;278(21):1759–1766. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03550210057039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]