Abstract

Background

The combination of coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) and myocardial CT perfusion (CTP) is gaining increasing acceptance, but a standardized approach to be implemented in the clinical setting is necessary.

Objectives

To investigate the accuracy of a combined coronary CTA and myocardial CTP comprehensive protocol compared to coronary CTA alone, using a combination of invasive coronary angiography (ICA) and Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) as reference.

Methods

Three-hundred eighty-one patients included in CORE320 trial were analyzed in this study. Flow-limiting stenosis was defined as the presence of ≥50% stenosis by ICA with a related perfusion deficit by SPECT. The combined CTA+CTP definition of disease was the presence of a ≥50% stenosis with a related perfusion deficit. All data sets were analyzed by two experienced readers, aligning anatomical findings by CTA with perfusion deficits by CTP.

Results

Mean patient age was 62±6 years (66% male), 27% with prior history of myocardial infarction. In a per-patient analysis, sensitivity for CTA alone was 93% specificity was 54%, positive predictive value (PPV) was 55%; negative predictive value (NPV) 93% and overall accuracy was 69%. After combining CTA and CTP, sensitivity was 78%, specificity 73%, NPV 64%; PPV 0.85% and overall accuracy was 75%. In a per-vessel analysis, overall accuracy of CTA alone was 73%as compared to 79% for the combination of CTA and CTP (p<0.0001 for difference).

Conclusions

Combining coronary CTA and myocardial CTP findings through a comprehensive protocol is feasible. While sensitivity is lower, specificity and overall accuracy are higher than assessment by coronary CTA when compared against a reference standard of stenosis with an associated perfusion deficit.

Keywords: Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography, Myocardial Computed Tomography Perfusion, Myocardial Perfusion Imaging, Multislice Computed Tomography, Hybrid Imaging

Introduction

The diagnosis and management of obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) has changed in recent years. While previous practice was supported by the results of invasive coronary angiography (ICA) alone to guide revascularization therapy, new guidelines recommend the assessment of related myocardial ischemia to proceed with percutaneous coronary intervention1.

Coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) is a well-established tool for the diagnosis of obstructive CAD, showing good accuracy to detect stenosis when compared to anatomical standards2-4. However, identification of epicardial obstructions related to flow limitations (and thus myocardial ischemia) is not an achievable goal using purely anatomical models5,6, and further tests are necessary to have this complementary information.

Recently, evaluation of myocardial computed tomography perfusion (myocardial CTP) has become feasible7. Prior studies have reported that CT perfusion imaging can help accurately diagnose CAD compared with various reference standards including single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), invasive coronary angiography, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, and fractional flow reserve8-13. These encouraging results stimulated the development of a multicenter, multinational trial to test the diagnostic performance of an integrated protocol of coronary angiography and myocardial perfusion by CT in a single exam, to detect stenoses related to perfusion deficits using SPECT-MPI and ICA as the reference14.

Combining anatomical and functional information provided by the same exam is a tremendous advance for the detection of stenosis related to abnormal myocardial perfusion. The ability to align coronary anatomy and myocardial territories by the same observer is an important goal to accomplish if we intent to make this promising technique available in the clinical setting.

The aim of this study was to test the diagnostic performance of a combined/comprehensive protocol to align the results of coronary CTA to myocardial CTP by the same reader, using the results of combined SPECT-MPI and ICA as the reference standard.

Material and Methods

Patient population

The CORE320 study (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00934037) is a multicenter prospective multinational study (16 centers, 8 countries) designed to evaluate the performance of coronary CTA and myocardial CTP in the diagnosis of obstructive CAD (>50% stenosis with a matching perfusion deficit), using the combination of ICA plus SPECT-MPI as the reference standard14-16. All 381 patients with complete imaging dataset reported in the main analysis were included in this secondary analysis.

Patients between 45 and 85 years of age clinically referred for ICA were included in the study. Exclusion criteria included: known allergy to iodinated contrast media, elevated serum creatinine (> 1.5mg/dl) or calculated creatinine clearance of <60ml/min, atrial fibrillation, second or third degree atrio-ventricular block, previous cardiac surgery, coronary intervention within the past 6 months, evidence of acute coronary syndrome with thrombolysis in myocardial infarction risk score ≥5 or elevated cardiac enzymes in the past 72 hours, high radiation exposure (≥5.0 rems) in the 18 months before consent and body mass index >40 m/kg2 among others16. The study design included coronary CTA, adenosine stress CTP, SPECT-MPI (in a validated CORE320 laboratory, within 60 days before invasive coronary angiography), and ICA.

CTA Image acquisition

CTA methods for CORE320 have been detailed elsewhere16. Briefly, rest imaging, including both coronary calcium scoring and coronary CTA, was performed before the stress CTP acquisition, all using a 320 × 0.5 mm row detector CT (Aquilion One, Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan). Prospectively ECG-triggered rest coronary angiography images were performed using iodinated contrast (Iopamidol 370 mg iodine/mL [50–70 mL] injected intravenously at 4.0-5.0 mL/sec) using bolus tracking in the descending aorta.

Myocardial CTP Image acquisition

The myocardial CTP acquisition protocol has also been described elsewhere16. After rest images were obtained, adenosine (140μg/kg/min) was infused continuously for 6 minutes, and a second bolus of iodinated contrast (Iopamidol 370 mg iodine/mL [50–70 mL] was injected intravenously at 4.0-5.0 mL/sec) using bolus tracking in the descending aorta, with a prospective ECG-triggered acquisition.

Coronary CTA and Myocardial CTP data analysis

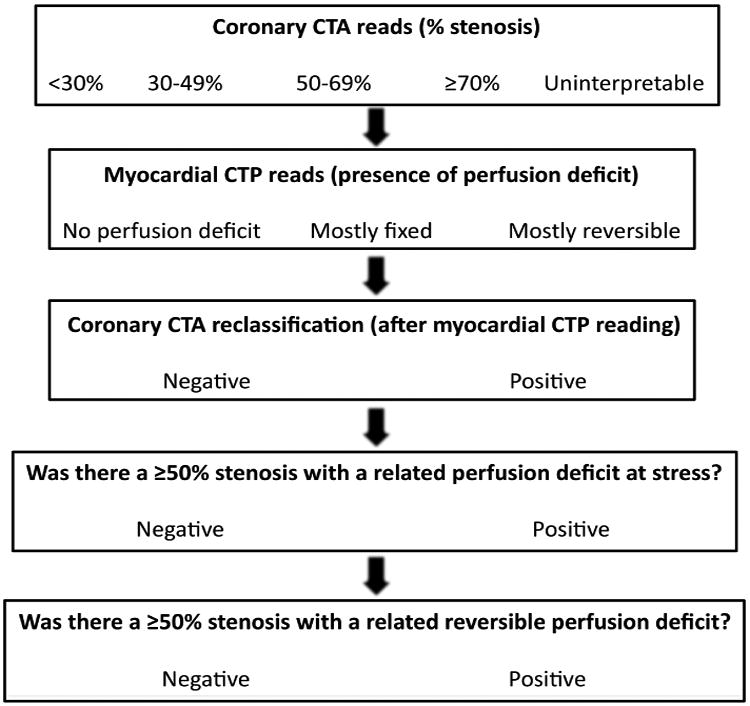

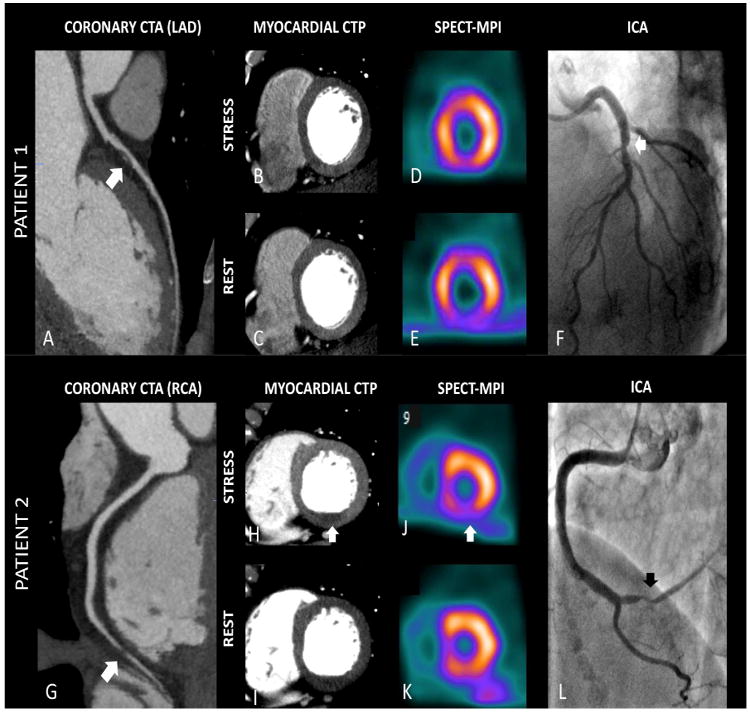

The raw data from calcium scoring, rest and stress scans were independently reconstructed and processed in a central laboratory. Two experienced readers analyzed both coronary CTA and myocardial CTP images using a Vitrea™ fX version 3.0 workstation (Vital Images, Minnetonka, MN, USA), through a stepwise approach (figure 1). The first step of the algorithm was coronary CTA interpretation, grading stenosis in main epicardial vessels and branches >1.5mm in diameter by visual assessment. When lumen analysis was compromised by artifacts, excessive calcification and/or stent with poor luminal assessment, the vessel was recorded as uninterpretable. Myocardial CTP assessment was performed using qualitative metrics, defined by presence of any perfusion deficit as well as its reversibility. Finally, the readers combined anatomical and perfusion information on a visual basis, according to individual anatomical variations, in order to match ≥50% stenosis with related fixed or reversible perfusion deficits (providing the definition of positivity for the combined analysis). Uninterpretable segments in coronary CTA that could be associated to reversible perfusion deficits were classified as “positive” for stenosis (≥50% stenosis). Additionally, readers were able to “reclassify” borderline or equivocal stenosis by CTA, upgrading or downgrading lesions according to the findings of the myocardial CTP analysis. Representative cases of combining CTA and CTP findings are displayed in figure 2.

Figure 1.

Workflow for interpretation of coronary CTA and myocardial CTP findings. CTA – Computed tomography angiography; CTP – Computed tomography perfusion

Figure 2.

Combining CTA and CTP data in diagnostic of flow-limiting stenosis. Patient 1 - (A) Left Anterior Descending (LAD) artery with a mixed plaque leading to an intermediate (50-69%) stenosis (CTA positive for ≥50% stenosis - arrow). (B, C) Stress/Rest images showing no evidence of perfusional deficits in anterior wall, with correspondent findings in SPECT-MPI (combined CTA + CTP negative for ≥50% stenosis with related perfusion deficit) (D, E). (F) Invasive angiography showing borderline stenosis in LAD (arrow), but with no relation to myocardial ischemia according to SPECT results (reference standard negative for ≥50% stenosis with related perfusion deficit). Patient 2 – (G) Significant stenosis in distal Right Coronary Artery (RCA) (CTA positive for ≥50% stenosis - arrow), with a corresponding perfusional deficit (most reversible) in left ventricle inferior wall ((H, I). Combined CTA and CTP was positive for ≥50% stenosis with related perfusion deficit. Reference standard images show similar reversible perfusion deficit in inferior wall by SPECT-MPI (J, K), and the related stenosis by ICA (L). CTA - Computed Tomography Angiography; CTP – Computed Tomography Perfusion; ICA – Invasive Coronary Angiography; SPECT –MPI – Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography – Myocardial Perfusion Imaging.

Reference Standard Imaging

The results of the combined assessment of ICA and SPECT-MPI (CORE320 reference standard) were independently evaluated in specific core laboratories, and have been previously described16. For ICA, coronary segmentation and quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) were performed using standard software (CAAS II QCA Research version 2.0.1 software, Pie Medical Imaging) for all lesions above 30% by visual assessment. Rest/stress 99mTc SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging was performed either using a treadmill exercise test or a pharmacological stress test (adenosine or dipyridamole) and the images were analyzed by two experienced readers. Flow limiting disease was defined on a per vessel-territory basis as ≥50% stenosis from ICA/QCA plus an associated myocardial perfusion deficit in SPECT-MPI (summed stress score [SSS]>0). Stenosis related to ischemia was defined as ≥50% stenosis by ICA/QCA with a related reversible perfusion deficit by SPECT-MPI (summed difference score [SDS]>0). A blinded adjudication was performed to align ICA and SPECT findings, using a dedicated algorithm17.

Statistical Analysis

Clinical and imaging databases were integrated and analyzed in the statistical core laboratory at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. The primary analysis compared the diagnostic accuracy of coronary CTA combined with myocardial CTP versus coronary CTA alone, using ICA/SPECT-MPI as the reference standard. The comparison was based on the parameters of sensitivity, specificity, predicted values and overall accuracy, using a cut-off of ≥50% stenosis for CTA alone, and ≥50% stenosis related to a perfusion deficit by myocardial CTP. All data are reported with 95% confidence intervals. For patient-level and individual vessel analyses, confidence intervals were calculated exactly by the binomial method. For simultaneous analysis of all vessels, GEE was used to account for repeated measurements within patients. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.2, Stata 11, and SPlus 8.0.

Results

Patient Population

All patients included in CORE320 study who had interpretable CTA and CTP scans were included in this analysis. Clinical and demographic characteristics of the 381 patients included in the analysis are displayed in Table 1. Additional data including patient flow, adverse events, radiation exposure and use of medications have been described in detail elsewhere14. The majority of the subjects was male (66%), with a previous history of coronary artery disease (confirmed by either history of documented myocardial infarction [27%] or percutaneous coronary intervention [30%]). Most of the patients were referred to ICA after presenting with anginal symptoms (83%).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | Median [IQR] or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 62 (56 – 68) |

| Male | 252 (66) |

| Body mass index (BMI), kg/m2 | 27 (24 – 30) |

| Race | |

| -White | 213 (56) |

| -Black | 40 (10) |

| -Asian | 123 (32) |

| -Other | 5 (1) |

| Diabetes | 131 (34) |

| Smoking | |

| -Current | 64 (18) |

| -Past | 133 (37) |

| -Never | 167 (46) |

| Dyslipidemia | 254 (68) |

| Hypertension | 297 (78) |

| Family history of CAD | 162 (45) |

| Prior history of myocardial infarction | 103 (27) |

| Prior history of revascularization (PCI) | 113 (30) |

| Asymptomatic | 26 (7) |

| Anginal Symptoms (typical or atypical) | 315 (83) |

| Non-Cardiac Chest Pain | 5 (2) |

BMI – Body Mass Index; CAD – Coronary Artery Disease; IQR – Interquartile Rage; PCI – Percutaneous Coronary Intervention.

Diagnostic performance of combined Coronary CTA and Myocardial CTP and Coronary CTA alone in the identification of flow-limiting stenosis

Diagnostic performance of coronary CTA alone to predict stenosis (QCA ≥ 50%), and myocardial CTP alone to predict perfusion deficits by SPECT (SSS ≥ 1) are displayed in table 2. At the patient level, diagnostic performance (overall accuracy) of combined CTA and CTP to detect flow-limiting stenosis was 0.75 (95%CI: 0.70–0.79), compared to 0.69 for CTA alone (95%CI: 0.64-0.75; p = 0.004 for difference) (table 3). In the group of patients with no prior history of CAD, combined CTA + CTP accuracy was 0.81 (95%CI: 0.76-0.86) while CTA alone was 0.72 (95%CI: 0.66-0.78; p<0.0001 for difference). These results were achieved mainly by a decrease in sensitivity (0.93 [95%CI: 0.88–0.97] vs. 0.78 [95%CI: 0.70–0.84]) and an increase in specificity (0.54 [95%CI: 0.47–0.60]) vs. 0.73 ([95%CI: 0.67– .79] comparing CTA alone to combined CTA and CTP, respectively for all patients) (table 3). Parameters of sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values at the patient level are also displayed in table 3.

Table 2.

Per-patient diagnostic performance of coronary CTA and myocardial CTP alone according to the respective gold-standard (n = 381).

| Group/Test | Gold Standard | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTA ≥ 50% or uninterpretable | QCA ≥ 50% | 93 (88-96) | 79 (72-85) | 87 (82-91) | 88 (81-93) |

| Any CTP perfusion deficit positive | Global SPECT ≥ 1 | 75 (68-81) | 54 (47-62) | 63 (56-69) | 68 (60-75) |

CTA – Computed Tomography Angiography; CTP – Computed Tomography Perfusion; PPV – Positive Predictive Value; NPV – Negative Predictive Value.

Table 3. Per-patient diagnostic performance of Combined Coronary CTA + myocardial CTP and coronary CTA alone for detection of flow-limiting stenosis*.

| Overall | Previous CAD | No previous CAD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| CTA | CTA+CTP | CTA | CTA+CTP | CTA | CTA+CTP | |

| Sensitivity, % | 93 (88-97) | 78† (70-84) | 89 (80-95) | 71† (60-80) | 98 (91-100) | 87† (76-94) |

| Specificity, % | 54 (47-60) | 73† (67-79) | 27 (17-40) | 57† (44-70) | 63 (56-70) | 79† (73-85) |

| PPV, % | 55 (48-61) | 64 (56-71) | 61 (52-70) | 68 (57-78) | 49 (40-58) | 60 (49-70) |

| NPV, % | 93 (87-96) | 85 (79-89) | 65 (44-83) | 60 (47-72) | 99 (95-100) | 95 (90-98) |

| Accuracy % | 69 (64-73) | 75† (70-79) | 62 (54-70) | 65 (56-73) | 72 (66-78) | 81† (76-86) |

Gold-standard definition for disease is a ≥50% stenosis by QCA with related SPECT SSS (Summed Stress Score) ≥ 1 in one of the three vessels: LAD, LCX, or RCA.

p<0.05 for difference from CTA alone by McNemar's test. Statistical comparisons of PPV and NPV were not performed.

CAD – Coronary Artery Disease; CTA – Computed Tomography Angiography; CTP – Computed Tomography Perfusion; PPV – Positive Predictive Value; NPV – Negative Predictive Value.

In a vessel-based analysis, the addition of CTP led to an improvement in the diagnostic accuracy of the combined analysis when compared to coronary CTA alone (0.79 [95%CI: 0.77-0.82] vs. 0.73 [95%CI: 0.70–0.76] respectively; p<0.0001 for difference) (table 4). The analysis of diagnostic performance of CTA and CTA + CTP in a specific vessel-territory approach showed non-significant increments in accuracies. Left anterior descending artery (LAD) was associated with higher sensitivity, but lower specificity values when evaluated with CTA + CTP. Combined CTA and CTP analysis in LCx and RCA territories showed low sensitivity, but high specificity for detection of flow-limiting stenosis (table 4).

Table 4. Per-vessel-territory diagnostic performance of Combined Coronary CTA + myocardial CTP and coronary CTA alone for detection of flow-limiting stenosis*.

| Overall | LAD | LCX | RCA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| CTA | CTA + CTP | CTA | CTA+CTP | CTA | CTA+CTP | CTA | CTA+CTP | |

| Sensitivity, % | 83 (77-88) | 58†† (51-64) | 86 (77-92) | 72† (62-81) | 81 (72-89) | 59† (48-70) | 81 (71-88) | 41† (31-52) |

| Specificity, % | 70 (66-74) | 86†† (83-88) | 60 (54-66) | 77† (72-82) | 78 (73-83) | 90† (85-93) | 72 (66-77) | 91† (87-94) |

| PPV, % | 45 (40-50) | 55 (48-61) | 40 (33-47) | 49 (40-58) | 52 (43-61) | 62 (51-73) | 46 (38-54) | 56 (43-69) |

| NPV, % | 93 (91-95) | 87 (84-90) | 93 (88-96) | 90 (86-93) | 94 (90-96) | 88 (84-92) | 93 (88-96) | 84 (79-88) |

| Accuracy % | 73 (70-76) | 79† (77-82) | 66 (61-71) | 76† (71-80) | 79 (74-83) | 83 (78-86) | 74 (69-78) | 79† (75-83) |

Gold-standard definition for disease is a ≥50% stenosis by QCA with related SPECT SSS (Summed Stress Score) ≥ 1.

p<0.05 for difference from CTA alone by Wald test (Overall) or McNemar's test (vessel-specific). Statistical comparisons of PPV and NPV were not performed.

indicates that statistical difference was also dependent on vessel.

CAD – Coronary Artery Disease; CTA – Computed Tomography Angiography; CTP – Computed Tomography Perfusion; PPV – Positive Predictive Value; NPV – Negative Predictive Value.

Discussion

The CORE320 study was designed to compare the performance of combined coronary CTA and myocardial CTP using as reference standard hemodynamically significant lesions defined as ≥50% stenosis by QCA related to perfusional deficits by SPECT-MPI. To minimize bias and consider CT under the most rigorous conditions, each of the four imaging modalities underwent blinded interpretation from independent core laboratories. This approach mandated a comprehensive mathematical strategy to correlate lesions between angiography and perfusion. However, for CT to be implemented in practice, CTP images will be used in conjunction with the CTA images by a single cardiovascular imager to improve management decisions. Thus, this study relaxes the methodology of the main paper to test a clinically realistic comprehensive protocol to integrate the anatomical and perfusion findings by the same reader.

The current methodology was design to validate a clinical workflow implementation, by integrating the CTA and CTP findings by the same reader (figure 1). On the other hand, the main CORE320 study performed independent coronary CTA and myocardial CTP analysis, and CTA and CTP readers independently recorded their findings in a database. In a second step, adjudication sessions were required to align coronary obstructions and perfusion deficits. This approach was imperative to avoid bias in both anatomy and perfusion interpretations, but it does not offer a straightforward algorithm to be implemented in the routine workflow.

In practice, we hypothesize that myocardial CTP can provide “tiebreaker” data when the CTA images reveal borderline lesions or when coronary segments are difficult to interpret because of dense calcium, stents, or other artifact. On the converse, CTA images can be useful to determine false-positive perfusion deficits related to artifacts (in those cases with no obstructions in the coronary CTA) or to help identify perfusion deficits related to microvascular disease. The rationale for integrating coronary CTA and myocardial CTP into a single read is based on the fact that the presence of coronary lumen obstruction identified by CT alone are not strongly related to ischemia18,19.

Smaller studies report combined coronary CTA and myocardial CTP interpretation. Rocha-Filho et al20 analyzed thirty-five high-risk patients referred to ICA with a stress-rest coronary CTA / myocardial CTP protocol. The high plaque burden likely limited the diagnostic accuracy for the coronary CTA alone; the positive predictive value increased substantially after inclusion of the myocardial CTP readings. Combined coronary CTA / myocardial CTP protocols were also applied in evaluation of patients with stents, using the same rationale – to overcome the limitation of luminal assessment by coronary CTA, with encouraging results21,22. Additionally, previous data highlighted the importance of myocardial perfusion deficits in prognosis, showing independent value to predict events in follow-up23,24.

Pilot data combining 320-detector-row coronary CTA plus myocardial CTP25, used the same reference standard and rest-stress CT protocol as CORE320 with an improved accuracy when CTP was added to CTA data. Overall, the accuracy assessed by the area under receiver-operator characteristics curve (AUC ROC) was better with the addition of myocardial perfusion assessed by CT (AUC ROC = 0.92 for coronary CTA alone vs 0.96 for coronary CTA + myocardial CTP, in both per patient and per-vessel analysis).

Using the CORE320 data myocardial CTP analysis when interpreted with coronary CTA substantially increased the specificity (with a drop in the sensitivity) to identify stenosis related to myocardial perfusion deficits. These findings were consistent among patients with and without previous CAD, both in per-patient and in per-vessel analyses. Unlike the original CORE 320 study, the same reader performed both coronary CTA and myocardial CTP reports in this analysis. The advantage of this approach is the simultaneous alignment between anatomy and perfusion. Notably, besides the increment in specificity in both per-patient and per-vessel levels, addition of CTP to standard CTA did not offer a substantial increase in positive predictive values.

The ability to detect rest and stress CT perfusion deficits with matched coronary stenosis using the same modality is promising. The ischemic burden related to coronary obstruction defines the best approach (either optimal medical treatment alone or combined with revascularization)26. This analysis showed that combined CTA+CTP is superior to CTA alone to detect stenoses matched to both rest and stress perfusion deficits (including non-viable infarcted areas) (table 4).

The results provided by this analysis support the implementation of a rest-stress coronary CT protocol in the clinical setting. After performing coronary CTA, if no evidence of obstructive lesion (≥50% stenosis) is found, the myocardial CTP could be aborted. Given the high negative predictive value of coronary CTA alone to identify stenosis related to myocardial perfusion deficits, the addition of myocardial CTP analysis in this scenario would not provide much useful information. However, if lesions above 50% (or uninterpretable segments) were identified, then myocardial CTP scan could be considered if clinical data (i.e., characteristics of symptoms, risk factors, etc.) and results of other tests (i.e, ECG, prior SPECT when available) were not enough to clarify the diagnosis of obstructive CAD.

We recognize some limitations in this study. The CORE 320 study protocol selected patients referred for invasive angiography (including patients with positive SPECT-MPI studies), which represent a selected population. Additionally, rest-stress CT protocols require intravenous administration of b-blockers before the perfusion images, which theoretically could interfere in the identification of ischemia27. However, given that CTA and CTP identified more false positives than false negatives, this effect was minimal14. Technical limitations related to the nature of the CTP exams, including artifacts related to motion and beam-hardening, were present in some scans, which contributed to false-positive results. The selection of SPECT-MPI as the perfusion reference standard was based on clinical availability and widespread acceptance. However, other modalities including MR perfusion or fractional flow reserve could offer better sensitivity. Finally, the addition of a stress phase for myocardial perfusion evaluation increases the exam duration.

Conclusions

Combined coronary CTA and myocardial CTP analysis is superior compared to coronary CTA alone in the identification of ≥50% stenosis by ICA related to myocardial perfusion deficits identified by SPECT-MPI. We also showed the feasibility of a comprehensive protocol to integrate the findings of both modalities by the same reader, in order to translate this novel approach to the clinical practice.

Highlights.

Combined coronary CT angiography and Myocardial CT perfusion is gaining acceptance.

Analysis of both methods by the same reader is feasible and superior to CTA alone.

A natural workflow is presented aiming the implementation in the clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

The study sponsor, Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation, was not involved in any stage of the study design, data acquisition, data analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Abbreviations list

- AUC ROC

Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristics Curve

- BMI

Body Mass Index (Kg/m2)

- CAD

Coronary Artery Disease

- CT

Computed Tomography

- CTA

Computed Tomography Angiography

- CTP

Computed Tomography Perfusion

- ECG

Eletrocardiogram

- GEE

Generalized Estimated Equations

- ICA

Invasive Coronary Angiography

- IQR

Inter-Quartile Range

- LAD

Left Anterior Descending Artery

- LCx

Left Circumflex Artery

- NPV

Negative Predictive Value

- PCI

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

- PPV

Positive Predictive Value

- QCA

Quantitative Coronary Angiography

- RCA

Right Coronary Artery

- SDS

Summed Difference Score

- SPECT-MPI

Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography – Myocardial Perfusion Imaging

- SSS

Summed Stress Score

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00934037.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:e44–e122. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.007. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG, et al. Diagnostic performance of 64-multidetector row coronary computed tomographic angiography for evaluation of coronary artery stenosis in individuals without known coronary artery disease: results from the prospective multicenter ACCURACY (Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography of Individuals Undergoing Invasive Coronary Angiography) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1724–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meijboom WB, Meijs MF, Schuijf JD, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography: a prospective, multicenter, multivendor study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:2135–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller JM, Rochitte CE, Dewey M, et al. Diagnostic performance of coronary angiography by 64-row CT. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2324–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rispler S, Keidar Z, Ghersin E, et al. Integrated single-photon emission computed tomography and computed tomography coronary angiography for the assessment of hemodynamically significant coronary artery lesions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1059–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meijboom WB, Van Mieghem CA, van Pelt N, et al. Comprehensive assessment of coronary artery stenoses: computed tomography coronary angiography versus conventional coronary angiography and correlation with fractional flow reserve in patients with stable angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:636–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi AD, Joly JM, Chen MY, et al. Physiologic evaluation of ischemia using cardiac CT: current status of CT myocardial perfusion and CT fractional flow reserve. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2014 Jul-Aug;8(4):272–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cury RC, Kitt TM, Feaheny K, et al. Regadenoson-stress myocardial CT perfusion and single-photon emission CT: rationale, design, and acquisition methods of a prospective, multicenter, multivendor comparison. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2014 Jan-Feb;8(1):2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blankstein R, Shturman LD, Rogers IS, et al. Adenosine-induced stress myocardial perfusion imaging using dual-source cardiac computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1072–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George RT, Arbab-Zadeh A, Miller JM, et al. Adenosine stress 64- and 256-row detector computed tomography angiography and perfusion imaging: a pilot study evaluating the transmural extent of perfusion abnormalities to predict atherosclerosis causing myocardial ischemia. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:174–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.813766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cury RC, Magalhaes TA, Borges AC, et al. Dipyridamole stress and rest myocardial perfusion by 64-detector row computed tomography in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:310–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.George RT, Arbab-Zadeh A, Miller JM, et al. Computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging with 320-row detector computed tomography accurately detects myocardial ischemia in patients with obstructive coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012 May 1;5(3):333–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.969303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bettencourt N, Chiribiri A, Schuster A, et al. Direct comparison of cardiac magnetic resonance and multidetector computed tomography stress-rest perfusion imaging for detection of coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Mar 12;61(10):1099–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rochitte CE, George RT, Chen MY, et al. Computed tomography angiography and perfusion to assess coronary artery stenosis causing perfusion defects by single photon emission computed tomography: the CORE320 study. Eur Heart J. 2013 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.George RT, Arbab-Zadeh A, Cerci RJ, et al. Diagnostic performance of combined noninvasive coronary angiography and myocardial perfusion imaging using 320-MDCT: the CT angiography and perfusion methods of the CORE320 multicenter multinational diagnostic study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:829–37. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vavere AL, Simon GG, George RT, et al. Diagnostic performance of combined noninvasive coronary angiography and myocardial perfusion imaging using 320 row detector computed tomography: design and implementation of the CORE320 multicenter, multinational diagnostic study. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2011;5:370–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerci RJ, Arbab-Zadeh A, George RT, et al. Aligning coronary anatomy and myocardial perfusion territories: an algorithm for the CORE320 multicenter study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:587–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.970608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Min JK, Leipsic J, Pencina MJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of fractional flow reserve from anatomic CT angiography. JAMA. 2012;308:1237–45. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuijf JD, Wijns W, Jukema JW, et al. Relationship between noninvasive coronary angiography with multi-slice computed tomography and myocardial perfusion imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2508–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocha-Filho JA, Blankstein R, Shturman LD, et al. Incremental value of adenosine-induced stress myocardial perfusion imaging with dual-source CT at cardiac CT angiography. Radiology. 2010;254:410–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09091014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magalhaes TA, Cury RC, Pereira AC, et al. Additional value of dipyridamole stress myocardial perfusion by 64-row computed tomography in patients with coronary stents. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2011;5:449–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rief M, Zimmermann E, Stenzel F, et al. Computed tomography angiography and myocardial computed tomography perfusion in patients with coronary stents: prospective intraindividual comparison with conventional coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1476–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Shaw LJ, et al. Incremental prognostic value of myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography for the prediction of cardiac death: differential stratification for risk of cardiac death and myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998;97:535–43. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.6.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Werkhoven JM, Schuijf JD, Gaemperli O, et al. Prognostic value of multislice computed tomography and gated single-photon emission computed tomography in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:623–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nasis A, Ko BS, Leung MC, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of combined coronary angiography and adenosine stress myocardial perfusion imaging using 320-detector computed tomography: pilot study. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:1812–21. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-2788-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden: results from the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial nuclear substudy. Circulation. 2008;117:1283–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zoghbi GJ, Dorfman TA, Iskandrian AE. The effects of medications on myocardial perfusion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:401–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]