Abstract

Background

Operating room (OR) to the intensive care unit (ICU) handoffs are known sources of medical error, yet little is known about the relationship between process failures and patient harm.

Materials and Methods

Interviews were conducted with clinicians involved in the OR-to-ICU handoff to characterize the relationship between handoff process failures and patient harm. Thematic analysis was used to inductively identify key themes.

Results

A total of 38 interviews were conducted. Dominant themes included early communication from the OR to the ICU, team member participation in the handoff, and relationships between clinicians; clinician perspectives varied depending substantially on role within the team.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that ambiguous roles and conflicting expectations of team members during the OR-to-ICU handoff can increase risk of patient harm. Future studies should investigate early postoperative ICU care as outcome markers of handoff quality and the effect of inter-professional education on clinician adherence to interventions.

Keywords: Critical care, patient handoff, qualitative methods, patient safety, quality improvement

Introduction

A patient handoff is defined as “the exchange between health professionals of information about a patient accompanying either a transfer of control over, or responsibility for, the patient.” Patient handoffs are ubiquitous in healthcare, and have been identified as significant contributors to medical error.(1–6) Intensive Care Units (ICUs) have a higher rate of adverse events as a result of medical error when compared to other hospital units, particularly in the case of patient handoffs from the operating room (OR) to ICU.(7) OR-to-ICU handoffs require (1) provision of acute care for a critically ill patient and (2) communication of essential clinical information to the accepting ICU clinicians, tasks that compete for attention.(8–10) The relative prioritization of either patient care or communication of clinical information often differs by type of clinician engaged in the handoff, which may lead to ineffective communication and breakdowns in the handoff process.

Prior interventions aimed at improving OR-to-ICU handoffs have predominately focused on protocols and tools for standardization. Although several interventions have led to increased clinician satisfaction, few studies have demonstrated reduced error or adverse event rates. The lack of evidence that handoff process improvements lead to improved patient outcomes has been, in part, attributed to a simplistic conceptualization of the handoff process and resulting uni-dimensional interventions.(1, 4, 7,11–13) Accordingly, qualitative research methods offer a unique ability to examine complex processes to generate new hypotheses. The goal of this study is to use qualitative research methods to describe clinician perceptions of OR-to-ICU handoffs, and to elucidate attributes of the handoff process associated with high quality, as well as with poor quality that can lead to patient harm.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a qualitative study using grounded theory methodology to explore clinician perceptions of the OR-to-ICU handoff. An email was sent to all clinicians who participate in the OR-to-ICU handoff of liver transplant recipients were eligible to be interviewed including all liver transplant surgeons, transplant fellows, trauma/critical care surgeons, transplant anesthesiologists, critical care fellows, surgical ICU nurses, and surgical residents who had rotated in the surgical ICU within the last year (a total of 45 eligible participants). Participants responded directly to the interviewer if they chose to participate.

Study Setting, Sample and Data Collection

The lead author (LMM) conducted in-person interviews in person after obtaining verbal consent. Two types of interviews were conducted: semi-structured cognitive interviews and unstructured critical incident interviews were conducted. The semi-structured, cognitive interview was part of a larger study in which a convenience sample of 2–3 participants/role in the team were asked to use the “think-aloud” method in the interviews to evaluate 38 attributes (e.g., team member presence, equipment functionality) of a handoff selected a priori from a review of the literature. Participant comments about handoff process failures were excerpted for qualitative analysis.(14) In the unstructured critical incident interviews, participants were asked to (1) describe their role, perceived responsibilities, and tasks performed during an OR-to-ICU handoff and (2) discuss potential failures in the handoff process based on their experience of participating in “problematic” handoffs. Handoff process failures were defined as any aspect of the OR-to-ICU handoff that “did not go as planned,” “presented a challenge to completion of the handoff,” or “placed the patient at risk of harm.” Participants were not compensated for study participation. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis by a professional transcription service. The study was approved by Northwestern University’s Institutional Review Board prior to collection of any data.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to identify recurrent themes about the OR-to-ICU handoff.(15) The analytic approach involved reading an initial group of transcripts, identifying possible themes through observation of patterns and repetitions, and then comparing and contrasting these themes within and across interviews to generate codes. Codes were then applied to a new group of transcripts, modified as needed, and any newly created codes were applied to the previous set of coded interview transcripts. Saturation of themes was determined when no new themes emerged from the interviews.

Results

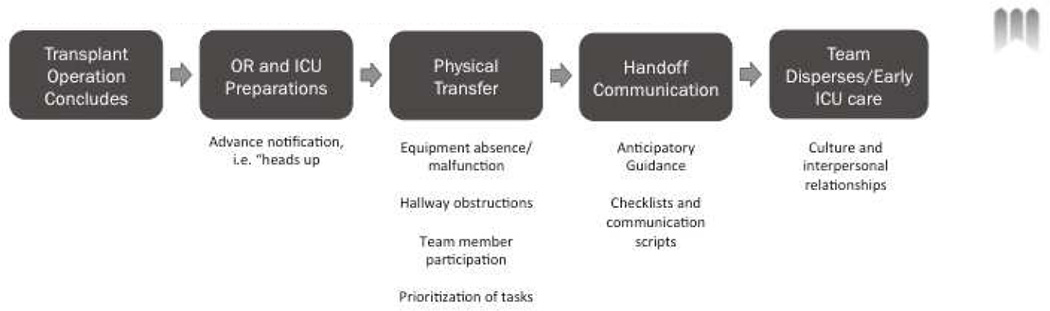

A total of 25 cognitive and 13 critical incident interviews were conducted and involved a total of 25 liver transplant surgeons and fellows, trauma/critical care surgeons and fellows, transplant anesthesiologists, anesthesia residents, surgical ICU nurses, and surgical residents. The identified themes are presented in chronological order, based on the stages of an OR-to-ICU handoff, which begins in the OR at the end of the transplant operation and ends with the initiation of postoperative care in the ICU (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

shows a schematic of the stages of an operating room to intensive care unit handoff.

Dominant Themes by Phase of the Operating Room to Intensive Care Unit Handoff

Phase I: Operating Room and Intensive Care Unit Preparations

ICU team members expressed the importance of getting a “heads-up” notification from the OR team and the need for early communication regarding the patient’s clinical stability and estimated time of transfer. ICU team members indicated that “advance notice” allows the ICU team to assemble, recruit assistance for handoff tasks, and prepare necessary equipment and supplies:

“A warning call from the operating room team…to the ICU can really help with communication and ease the transition once the patient arrives.” (ICU resident)

The value and purpose of a “heads-up” varied among team members. Surgical residents reported that a “heads-up” enabled them to better anticipate and balance the workload of receiving a new patient while providing ongoing care to other ICU patients, thereby avoiding the possibility of compromising the safety of either type of patient. Anesthesiologists and anesthesia residents focused on the content of information transferred at the time of the “heads-up.” For example, anesthesia providers described a lack of involvement in the communication between the OR and ICU that occurs at the end of the transplant operation. Despite this lack of involvement, they also acknowledged the importance of early OR-to-ICU communication, in order to facilitate ICU anesthesia-related preparations:

“I think the nurses in the OR don’t…seem to facilitate the transfer, at least in a way that I can understand very well.. I'm just not sure what goes on there.” (Anesthesia resident)

In contrast, ICU nurses described the “heads-up” as a process that enabled them to gather supplies and prepare equipment prior to the patient’s arrival. Not receiving a “heads-up” resulted in ICU staff feeling underprepared for the patient’s care needs or not having the proper equipment available for the transfer:

“The coordination, you know, how to start setting up the ICU…. it’s important because [the OR team] can really prep the nurse that’s taking over care… just to have the right equipment there… to make it more efficient because then they have [the equipment] ready and you’re not waiting for them upon transfer.” (ICU RN)

Phase II: Physical Transfer

Obstructions and Equipment Failure

Anesthesiologists elaborated on the challenges encountered during the physical transport of a patient from the OR to the ICU and the resulting potential for patient harm. These problems were perceived to be more common in surgeries occurring at night when the path from the operating room to the ICU can be obstructed by cleaning equipment and materials used for restocking supplies:

“There’s equipment in the hallway that makes it difficult to move [the patient] to the ICU…if you have a really unstable patient with a separate IV pole, the person carrying the IV pole gets tripped up and stops. If the bed doesn’t stop and the IV pole stops then you’re going to pull out some lines and I've seen that.” (Anesthesiologist)

“I know of [a] patient whose [pulmonary artery] catheter was pulled out during transfer to the ICU bed because something got caught because they were not really completely organized.” (Anesthesiologist)

Team Member Participation during a Handoff

Nearly all participants recognized the importance of the presence and participation of team members during a high-quality handoff. Attending surgeons listed the physical presence of the operative surgeon and anesthesiologist as critical for effective handoff communications:

“The surgeon, being the captain of the ship, should know all of the issues that anesthesia’s been having intraoperatively so…I think the importance and the onus is on the surgeon, not on anesthesia.” (Transplant Surgeon)

“Anesthesia has been handling the [vasopressor medications] and the vent and the airway… Surgeons will have to… throw in their two cents …so I think it’s a combined effort. Probably more so anesthesia than surgery but definitely both.” (Critical Care Surgeon)

In contrast to the surgeons, however, trainees focused more on the ICU nurse as the central team member whose presence is required for a high-quality handoff:

“I think as long as things are communicated to the RN, what needs to be done for the patient, whether on a whiteboard or verbally or somehow. I don’t think [OR team members] need to sit there for the whole thing…. ideally if the anesthesia, the surgeon, the RN and the ICU resident are all in the same room and heard everything, I mean, [it] just makes sense” (Critical Care Fellow)

Prioritization of Tasks: Clinical Care or Handoff Communication

Several participants discussed the issue of relative prioritization of tasks following arrival of the patient in the ICU. They identified a conflict between the initiation of clinical care including the exchange of transport equipment (e.g., IV poles, ventilator) to ICU equipment and initiation of vital sign monitoring and documentation with the need for ICU team members to participate in the handoff. Due to the often acute and complex clinical care needs of the patient, ICU nurses reported that initiation of ICU care was a higher priority task necessary to ensure patient safety than immediately initiating the handoff.

“I think the biggest thing is things that potentially get missed when we’re trying to settle the patient in and … [OR team members] just start talking … You see me crazy busy, …Just like give me like, even five minutes, like so I can see that their blood pressure is not [grossly abnormal]” (ICU RN)

On the other hand, OR team members felt that handoff communications should be a priority and were concerned that the tasks of initiating ICU care of the patient interfered with the handoff information exchange between OR and ICU team members. Most anesthesiologists and anesthesia residents expressed frustration with the delay in the handoff communication resulting from initial ICU care of the patient and discussed the difference in perspective between anesthesia and ICU nursing specifically in terms of what constitutes an “urgent” care task:

“What a nurse may consider…as an urgent patient care thing may be different from what we consider as urgent… If the patient is… unstable, the whole team, the anesthesia care provider and the nurse have to work on that before they can do the handoff… but …[unstable] is going to mean something very different to the ICU nurses than it means to us.” (Anesthesiologist)

“I understand the nurses have a job to do, I understand there’s a mess of wires that they want to organize quickly but often times I feel like the focus is on organizing the patient lines and not paying attention to the handoff by the anesthesia care provider. Sometimes they ask stuff that I might have already… gone over. If I know that it’s something I really want them to know for patient safety… I would get their attention and emphasize it, but it’s not as efficient to do it that way.” (Anesthesiologist)

Some team members specifically commented on the need for extra ICU nurse staffing during the handoff to allow the primary ICU nurse to participate in the handoff communication without being preoccupied with care of the patient:

“Having multiple nurses available and having the nurse that’s going to be taking care of the patient primarily there to communicate with the team and not be like running to get…blood from the blood bag or do whatever… that’s really important.” (ICU resident)

“[Ideally] the main nurse is there and like three of her [colleagues] come in who aren’t responsible for the patient and the three [colleagues] work very hard to hook up all the IVs, to put on the monitors to make sure that the monitor is working, to make sure the vent is working if they need it and the main nurse listens to the handoff and I think that’s what, that I see is ideal.” (Transplant surgeon)

Phase III: Handoff Communication

Anticipatory Guidance

Several participants noted the need for increased communication about potential patient risks and complications during the handoff was important to facilitate optimal response to these issues by the ICU team, as opposed to a communication focused on details of the operative procedure and presentation of data (e.g., estimated blood loss, fluid administration), documented in the Electronic Health Record (EHR):

“The biggest thing when I sign out to the nurses is my anticipatory guidance…Telling them the amount of fluids that we got, the position of the ET tube, even the vent settings, the position of the different lines for access, is not necessarily important… But… anticipatory guidance…[is] important.” (Anesthesia resident)

“I really believe communication is essential to avoid mistakes. When we have indirect communication or third-hand communication, I think it’s not safe or effective.” (Transplant surgeon)

However, when describing ideal communication patterns, ICU team members reflected that the ideal rarely occurred:

“’This is what we did during the case, this is what the patient came with, this is what we did, these were the complications, where we’re going from here, this is our plan,’ getting the anesthesia and the nurse in the conversation too I don’t think I ever did that.” (ICU fellow)

Distractions and Interruptions during the Handoff

Several ICU team members felt the ICU setting fits poorly into traditional patient safety paradigms, and noted that attempts to eliminate interruptions may compromise patient safety by inappropriately prohibiting ICU clinicians from responding to the needs of other critically ill ICU patients in the ICU.

“[No interruptions] just may not be realistic …if you get a page where there’s an emergency and you have to answer it … an interruption maybe sometimes cannot be avoided. I think there are times that something just happens, like…’ the patient next door just had a 27 beat run of VTAC and his pressure is 40’.” (ICU resident)

“People like to say patient safety is so paramount, and ‘If only we were more like the commercial aviation business.’ Well, yes, but if taking care of patients were the same as commercial aviation, I would never operate, because pilots don’t fly in [a] storm… The reality of being in an ICU is they get three admissions at once and they’re all really sick… So I don’t think [eliminating interruptions] should be mandated, because it could potentially not make things worse for that patient, but make things worse for two other patients who are also under your care.” (Critical Care Surgeon)

Using Checklists and Communication Scripts to Facilitate Handoff

While most participants acknowledged that a checklist could be valuable as a reminder of critically important handoff information, several participants expressed concern about the additional workload created by checklists and associated documentation.

“The last thing we need is… another note to write, because we already have to write the ICU H&P, and then make sure all the orders are correct, and then add in all the orders that the fellow didn’t order… and all of the little things that we put in there for the ICU… that the transplant team doesn’t… I understand why you want to document from a quality standpoint, but it’s just tough because the resident does not need another piece of paperwork” (ICU Resident)

ICU team members also commented on the high rates of errors within postoperative electronic order sets and the unintended consequences of the errors, and described how errors in electronic order sets were more likely to cause unintended consequences for patients who were being transferred during the night. The issue was exacerbated by inadequate nurse staffing or inexperienced nurses or residents:

“That [postoperative] order set will go away when there is a bad consequence, when something bad happens. I can see it happening. That future order set is the worst thing ever invented I think. Because it makes nobody accountable for their actions, not one person.” (ICU RN)

The Influence of Culture and Interpersonal Relationships on Handoff Quality

A dominant theme amongst participants was the effect of institutional culture and interdepartmental relationships on behavior during the handoff. Participants specifically noted the effect of interpersonal dynamics between team members and described how collegiality affects subsequent patient care. Attending ICU surgeons commented on the changing culture of surgery and its effect on improving patient safety through reduction of the hierarchy and increased transparency:

“I page the fellow…, but again why am I talking to a fellow? Why am I not talking to an attending? Because the attendings are not very responsive. [Their response is] usually delayed, it’s not very collegial” (Critical Care Surgeon)

“Somebody who is scared to talk to a transplant [surgeon] attending is going to be scared to talk to a transplant [surgeon] attending even if they say ‘Are there any questions?’….I see that in the OR all the time…clearly [in] some ORs [team members] are not going to say a word just because they can’t stand that vibe from the attending and I think that that’s probably true with the handoff too….” (Critical care surgeon)

Participants also resented the fact that interpersonal dynamics created inconsistencies in the handoff process. In particular, they mentioned the variation between different surgical team members and how, even one difficult team member can discourage communication and compromise patient safety. The influence of interpersonal team dynamics was acknowledged by critical care surgeons about communications with the transplant surgeons, and by anesthesia about communications with ICU residents:

“A relationship with [the attending] is critical to being able to… put yourself in a somewhat vulnerable position as a resident and provide your assessment… When you’re with a fellow it’s more likely that I'm able to at least say, ‘This is what I think is going on, what do you think?’….With an attending, depending on who…. I better keep my damn mouth shut, like, this guy doesn’t even want to hear about the data.” (Anesthesia resident)

“The [trauma] attendings here…try to empower the residents to contact the transplant fellow or page the attending…Technically I could page Dr. [transplant surgeon], but you know it’s not a reality. If you page an attending at night, it’s a failure, you have failed as a resident.” (ICU resident)

Discussion

Research evaluating the connection between patient handoffs and postoperative medical errors and adverse events is limited by several factors including a lack of universally accepted process and outcome metrics and a high rate of susceptibility to patient or treatment selection biases. Interventions are commonly evaluated based on handoff-related outcome measures such as clinician satisfaction or communication effectiveness.(11) It is challenging to determine causality using quantitative studies, specifically elucidating whether handoffs are of poorer quality for complex patients or whether poor quality handoffs lead to worse outcomes. Therefore, new metrics to assess the actual quality of a handoff are needed.

These findings illuminate several key elements of a handoff that appear to influence patient safety, including early OR-to-ICU communication, the relative prioritization of clinical care versus participation in the handoff communication, and the role of inter-personal relationships within and between OR and ICU teams. Participants highlighted the connection between handoff quality and the quality of early postoperative care, noting a decreased ability of the ICU team to rapidly triage early postoperative complications in the wake of a poor handoff, Furthermore, participants described the prominent role of technology, equipment, and the EHR in the handoff process, noting how technological problems and equipment malfunctions or absence can increase the risk of patient harm. New handoff themes such as importance of additional nursing staff to assist the primary RN, the need for handoff communication focused on anticipatory guidance rather than operative details, and the influence of culture on team communication were revealed.

The Joint Commission designated handoff standardization as a National Patient Safety goal, encouraging the use of checklists and protocols to guide communication and structure clinical activities. In addition, a recent review of the literature by Segall et al. summarized recommendations for postoperative handoffs including use of checklists and protocols, urgent task completion prior to information transfer, limiting conversations while performing tasks, and adopting the “sterile cockpit” approach (i.e., allowing only patient-specific discussions during the verbal handover).(13) However, participants in this study expressed concerns about the unintended consequences of such protocols, indicating that in some situations they may actually lead to harm.(16, 17) For example, electronic order sets, which are designed to minimize postoperative care errors, were perceived to be dangerous by ICU and OR team members due to poor design. Study participants also questioned whether traditional patient safety paradigms and analogies with other high-risk industries, such as aviation, are a good model for healthcare given the typical instable and unpredictable status of ICU patients. There was general agreement on the benefits of minimizing interruptions and distractions, but with agreement that neither can be fully avoided without increasing the risk of harm to other patients in the ICU. Clearly, there is a need for proactive, risk assessment of these recommendations prior to implementation on a wide scale. This study also points to the need for the development of new quantitative metrics to fully evaluate the quality and fidelity of a new hand-off process, including a measure of communication prior to the ICU transfer, documentation of equipment malfunction or absence, and ICU response to early postoperative complications.

Institutional culture and inter-departmental relationships were also reported to greatly influence behavior during a handoff. Members of the OR and ICU teams described different priorities for a high quality handoff process, including the optimal timing and content of handoff communication, as well as whether handoff communication should take priority over initiation of clinical care in the ICU. The varied opinions among participants demonstrate the potential success of interventions that clarify roles, responsibilities, and expectations. Finally, interpersonal dynamics between team members was reported to lead to inconsistency a handoff and there was general recognized that even a single “difficult” team member could compromise patient safety by discouraging open communication.

The need for consensus building among team members and addressing interpersonal conflicts among and within teams cannot be overstated. The findings underscore that differing expectations by members of a multidisciplinary team of the handoff process can potentially contribute to medical errors. Inter-professional education (IPE), or interactive cooperative learning by multidisciplinary team members for the purpose of improving inter-professional collaboration, may be a potential strategy. A recent Cochrane review identified 15 studies that measured the effect of IPE on process and clinical outcomes.(18) Seven of the studies reported improvement in patientcentered communication, reduced errors by emergency department teams, and improved team behaviors and information sharing for operating room teams. The OR-to-ICU handoff may prove a fertile setting for a randomized control trial to examine the effectiveness of IPE in improving handoff quality compared to separate clinical context, specialty or profession-specific interventions.

Despite the rich data obtained during interviews, this study has several methodological limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small and limited to transplant clinicians. Transplantation was chosen as a clinical context of care because of the complexity of transplant patients and the consistency with which they are transferred to the ICU from the OR. The findings from this study would need further evaluation to determine the degree to which they are generalizable to other contexts of surgical care, such as cardiothoracic surgery.

Clinicians perceive that handoff quality influences subsequent care and patient safety although they differ in perspective about which elements of the handoff are most closely tied to safe patient care. Future quantitative research should include metrics that capture the quality of initial OR-to-ICU handoff communication during the final phases of the operation, team member participation during the handoff, as well as metrics that capture patient outcomes such as ICU team response to early complications after transfer. Interventions should consider using IPE to clarify roles, responsibilities, and expectations among the members of multi-disciplinary hand-off teams.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work is funded by AHRQ and NIDDK T32 Training Grants (McElroy 5T32HS000078-15, T32DK077662).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Lisa M. McElroy, Email: lisa.mcelroy@northwestern.edu.

Kathryn R. Macapagal, Email: Kathryn.macapagal@northwestern.edu.

Kelly M. Collins, Email: collinsk@wudosis.wustl.edu.

Michael M. Abecassis, Email: mabecass@nmh.org.

Jane L. Holl, Email: j-holl@northwestern.edu.

Daniela P. Ladner, Email: dladner@nmh.org.

Elisa J. Gordon, Email: e-gordon@northwestern.edu.

References

- 1.Cohen MD, et al. The published literature on handoffs in hospitals: deficiencies identified in an extensive review. Quality & safety in health care. 2010;19(6):493–497. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.033480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arora VM, et al. Hospitalist handoffs: a systematic review and task force recommendations. Journal of hospital medicine : an official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2009;4(7):433–440. doi: 10.1002/jhm.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger JT, et al. Patient handoffs: Delivering content efficiently and effectively is not enough. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2012;24(4):201–205. doi: 10.3233/JRS-2012-0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster S, et al. The effects of patient handoff characteristics on subsequent care: a systematic review and areas for future research. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2012;87(8):1105–1124. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31825cfa69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitch BT, et al. Handoffs causing patient harm: a survey of medical and surgical house staff. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety / Joint Commission Resources. 2008;34(10):563–570. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ong MS, et al. A systematic review of failures in handoff communication during intrahospital transfers. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety / Joint Commission Resources. 2011;37(6):274–284. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothschild JM, et al. The Critical Care Safety Study: The incidence and nature of adverse events and serious medical errors in intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(8):1694–1700. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000171609.91035.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Vos ML, et al. Implementing quality indicators in intensive care units: exploring barriers to and facilitators of behaviour change. Implementation science : IS. 2010;5:52. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petrovic MA, et al. Pilot implementation of a perioperative protocol to guide operating room-to-intensive care unit patient handoffs. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2012;26(1):11–16. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pickering BW, et al. Identification of patient information corruption in the intensive care unit: using a scoring tool to direct quality improvements in handover. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(11):2905–2912. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a96267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abraham J, et al. Ensuring patient safety in care transitions: an empirical evaluation of a handoff intervention tool. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2012;2012:17–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McFetridge B, et al. An exploration of the handover process of critically ill patients between nursing staff from the emergency department and the intensive care unit. Nurs Crit Care. 2007;12(6):261–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2007.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Segall N, et al. Can we make postoperative patient handovers safer? A systematic review of the literature. Anesth Analg. 2012;115(1):102–115. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318253af4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis CH. IBM, editor. Using the "Thinking Aloud" Metod in Cognitive Interface Design. 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morse JaFP. Qualitative research methods for health professionals. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joy BF, et al. Standardized multidisciplinary protocol improves handover of cardiac surgery patients to the intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(3):304–308. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181fe25a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zavalkoff SR, et al. Handover after pediatric heart surgery: a simple tool improves information exchange. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(3):309–313. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181fe27b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reeves S, et al. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes (update) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD002213. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]