Living Donor Transplantation

Solid organ transplantation as a treatment for end stage organ failure has been an accepted treatment option for decades. As surgical techniques advance, new medications are developed to prevent rejection, and the management of side effects has improved (1). Patients are also living longer and have greater quality of life after transplantation (1). Currently patients can receive liver, kidney, pancreas, heart, lung and intestinal transplants in the United States. Additionally, other combinations of organs, such as liver/kidney, kidney/pancreas, lung/liver, and heart/kidney are performed in certain situations. Vascularized Composite Allografts (VCA) is among the recent advances in transplantation. This refers to a transplant composed of several different kinds of tissues (i.e., skin, muscle, bone), such as those in the hand, arm, or face, transferred from donor to recipient as a single functional unit (2). Living donors are currently being considered by the United Network for Organ Sharing as an option for VCA transplants.

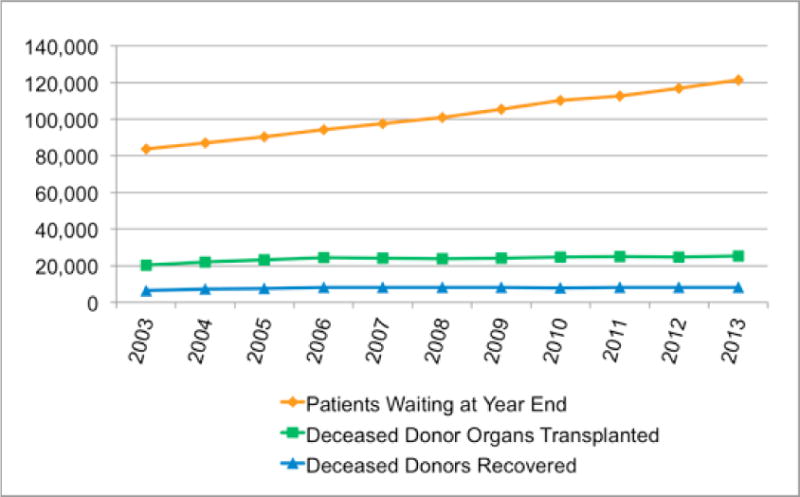

Regardless of the type of transplant performed the limiting factor is often the shortage of viable deceased organ donors of appropriate quality. Despite advances in medicine and technology, and increased awareness of organ donation and transplantation, the gap between supply and demand continues to widen (1). The number of people on the national waiting list continues to grow, but deceased organ donation rates and number of transplant surgeries performed remains stagnant (Figure 1). With the stagnation in deceased donor transplantation, we have seen a rise in living donor transplantation.

Figure 1.

Organ Donation and Transplantation in the United States

The first successful living donor transplant was performed in identical twins in 1954 with a kidney (3). Utilizing identical twins negated the need for immunosuppression. In fact some of the first live donor advocates were involved in early living donor transplantation ensuring that the interests of the donor were preserved while pursuing kidney transplantation in the recipient. Living donor kidney transplantation saves and improves the quality of life of those with kidney failure (4). Relative to deceased donor kidney transplantation, live donor kidney transplantation has superior graft and patient survival rates, lower acute rejection rates, avoids or reduces the need for dialysis, pre-empts rapidly deteriorating quality of life, and is more cost effective than deceased organ transplantation (1,4–5). Living kidney donor outcomes are generally favorable, with low mortality and morbidity, moderately high psychological benefit, and very low rates of regret, however there are not enough live donor surgeries to meet the demand of the large waitlist (6–9). The Renal and Lung Living Donors Evaluation Study (Relive) examined health related quality of life in kidney donors and 80% of the 2455 kidney donors in the study reported average or above average health for their age at follow up (10). Kidney donors with impaired health were more likely obese, have a history of psychiatric disorders and come from a racial minority background. One percent reported that kidney donation affected their health in a negative way. Predictors of depression post-kidney donation included, non-white race, younger age, longer recovery post-donation, greater financial burden and feelings of moral obligation (11).

Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) is most common with adults donating to children with biliary atresia utilizing the left lateral segment of the liver as this caries much less risk to the live donor than when the donation is to an adult because less liver volume (20%) is removed (12). The liver’s regenerative capacity ensures the liver grows to be adequate size in both the donor and recipient. Pediatric live liver donation, however, is psychosocially complex as a family is met in crisis as they have a child in need of a lifesaving transplant. Parents are faced with the decision as to whether they should put their own life at risk to save their child. Adult to adult LDLT, on the other hand, is only an option for a selective group of patients with end stage liver disease, especially in geographical regions of the country where the rates of a deceased donor transplant is lower and there is increased death on the waiting list (13). Done currently in only a few centers in the United States, right lobe living liver donor hepatectomy (lobe donated routinely in adult to adult LDLT) carries increased morbidity and mortality to the donor and recipient compared to kidney donation but is still believed to be an acceptable solution to the shortage of deceased donors at experienced centers (13,14). The NIH sponsored A2ALL study, concluded that selective recipients have good outcomes with LDLT; however increased donor and recipient age, elevated creatinine levels, a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatitis C, and recipient intensive care stay prior to transplant all increase the chance of recipient mortality (13,15). The liver donors experience complications as well, A2ALL reports a 40% liver donor morbidity rate with most not considered life threatening (16). Psychological complications occurred in only 3% of donors. Despite the high morbidity, living liver donors report psychological benefit and satisfaction with the donation experience (9,17). Long-term liver donors were found to have above average physical and mental components scores on the SF-36. (17,18) Although feasible, few lung, pancreas and intestine live donor transplants have been performed in the United States (1).

Types of Living Donors

Initially, living donors were genetically related to the recipient. As improved immunosuppression regimens were developed and transplant programs comfort with live donation evolved the living donor pool has expanded. Family, spouses, friends, and community members may be evaluated for living donation. Additionally non-biological or emotionally related donors often referred to as non-directed donors or altruistic donors, present to transplant programs to donate and a greater number of transplant programs are accepting these donors for both kidney and liver donations. At times transplant candidates or their families will utilize social media to solicit for live donors and there are certain groups that help a person find a living donor. This can create many challenges for the live donor team with regard to evaluation of the motivations for donation.

Donor Medical Evaluation

Increasing numbers of transplant programs have designated teams of professions involved in the living donor evaluation. This includes a donor surgeon, medical physicians (nephrologist/hepatologist), transplant coordinator, independent living donor advocate, fiscal/transplant credit analyst, social worker, dietitians, and psychologist/psychiatrist. If the team is devoted exclusively to the living donor’s evaluation, surgery, and post-surgical care and the health care professionals are not routinely involved with the transplant candidates, a Living Donor Team, rather than just an advocate, may provide an independent evaluation of the donor. An ethics consult may also be recommended for directed donations with those who have no emotional or biological relation to the candidate or “altruistic” donors. This ensures that donors receive the assessment and education needed to make an informed choice regarding living donation.

“The person who gives consent to be a live organ donor should be competent, willing to donate, free from coercion, medically and psychosocially suitable, fully informed of the risks and benefits as a donor, and fully informed of the risks, benefits, and alternative treatment available to the recipient” (19).

The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) policies have standardized the components of the live donor evaluation in the United States (20). The goal of the medical evaluation is to determine suitability by assessing immunological compatibility; general health of the donor; surgical risk for the donor; anatomy of and function of intended organ for donation; and identifying if there are any diseases present that may be transmitted from the donor to the recipient; and educating the donor on individual risks based on assessment and existing data.

Over sight of living donor transplantation

In the early 2000s live donor transplantation reached an all-time high (1). Most kidney transplant programs and many liver transplant programs in the United States were offering live donor transplants (1). There were also two liver donor deaths that reached the media and resulted in a consensus meeting in 2000 (21). As a result of this meeting, increased oversight of living donor transplantation has occurred (20–23). Both the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) developed regulations that transplant programs performing live donor transplantation were asked to comply with (20–23) These regulations involve the education, evaluation, informed consent process and donor follow-up required for living donor care. Transplant programs performing live donor transplants are routinely audited to ensure compliance with all living donor regulations. Two areas in which had significant changes included the psychosocial and the Independent Living Donor Advocate (ILDA) evaluation. The psychosocial evaluation has long been part of the medical evaluation of transplant candidates and more recently living donors. However, new components have been added to the evaluation process and are outlined below.

Furthermore, one of the new requirements was to have an ILDA who is not involved routinely in the care of the transplant candidate and assigned to each person considering live donation. The interpretation or the regulations surrounding the ILDA and the practical implementation of the role have been met with much controversy and varies across the country (24). Standardization of the role and clarification regarding the qualifications of the professionals implementing the role is warranted and recommendations have been suggested to standardize the practice of ILDAs (25, 26). The purpose of this paper will be to outline the current regulations and guidelines associated with the psychosocial and ILDA evaluation but also to provide additional recommendations with regard to the evaluation of living donors.

The Psychosocial Evaluation of Living Donors

Goals and Timing of the Living Donor Psychosocial Evaluation and Education

According to UNOS, the goals of the psychosocial evaluation are to: (1) identify and appraise any potential risks for poor psychosocial outcomes, including risks related to the individual’s psychiatric history or social stability; (2) ensure that the prospective donor comprehends the risks, benefits and potential outcome of the donation for herself or himself and the recipient, and that the donor understands that the data on long-term donor psychosocial outcomes continue to be sparse; (3) assess the donor’s capacity to make the decision to donate and ability to cope with the major surgery and related stress; (4) assess donor motives and the degree to which the donation decision is made free of guilt, undue pressure, enticements or impulsive response; (5) review lifestyle circumstances (e.g., employment, family relationships) that might be affected by donation; (6) determine that support systems are in place and ensure a realistic plan for donation and recovery, with adequate social, emotional and financial support and resources; and (7) identify any factors that warrant educational or therapeutic intervention before donation can proceed (22).

The psychosocial evaluation is conducted when the donor presents to the transplant center for a face to face evaluation. Depending on the center and the organ transplanted, the evaluation could be performed in one day or across several days. The ILDA and psychosocial evaluation at some centers are performed through the use of telemedicine; however some portion of the medical evaluation requires a face to face visit between the donor candidate and physicians. If the donor has a complex psychosocial history, the evaluation may be completed in multiple meetings to gather additional information. It may be beneficial to obtain collateral information from other health care professionals (e.g., therapist, psychiatrist) if the donor candidate is undergoing psychiatric treatment. While not mandated, some transplant centers use separate clinicians for the transplant recipient psychosocial evaluation and live donor evaluation to help decrease any conflict of interest.

The psychosocial evaluation should be conducted in a private area with no other persons present, including the transplant candidate or family members. However, it may be appropriate for family members to be present, at times, when discussing the care and transportation plan for post-donation care. If family or friends are not present at the time of the evaluation, it may be appropriate for the clinician to discuss by phone, information regarding post-donation care and transportation with the donor’s permission. The health care provider usually confirms that the friend or family member will provide support and transportation and this is then documented in the donor’s medical record. If the potential donor requires an interpreter, it should be a professional interpreter and not a family member, friend, or translator related to the candidate.

When the psychosocial evaluation results in recommendations for intervention prior to donation (e.g., drug or alcohol rehabilitation, treatment of depression, weight loss), the potential donor should have the option to return for a second evaluation to determine if s/he has met the recommendations proposed by the health care professional who completed the evaluation. If the potential donor has not completed the recommendations, subsequent treatment and evaluations may be recommended.

Health Care Professionals Performing the Psychosocial Evaluation and Education of Living Donors

The United Network of Organ Sharing recommends that the psychosocial evaluation to be completed by a licensed social worker, psychologist, and/or psychiatrist familiar with the transplant process (22). Whenever possible, the person conducting the evaluation should be independent from the care of the candidates and recipients at the transplant center. The UNOS requires that the social worker have the minimum of a Master’s degree and the evaluator themselves should have an understanding of the entire donation process. The three health care providers outlined in the UNOS guidelines were chosen as they have the necessary training and clinical skills to make a diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder which may impair the donor’s ability to make an informed decision, understand the risks, or cope with potential complications after surgery.

Components of the Psychosocial Evaluation

To meet these goals outlined by UNOS, the following areas to be assessed as part of the psychosocial evaluation include: the history and current status of the donor; capacity; psychological status; relationship with the transplant candidate; motivation for donation and other altruistic or voluntary behavior history; donor knowledge, understanding, and preparation; social support including education and availability of post-operative care and transportation; and financial suitability (22). Table 1 below provides the required areas recommended by UNOS as well as additional areas recommended by these authors to make a determination of the donor’s suitability for surgery from a psychosocial perspective.

Table 1.

| PSYCHOSOCIAL EVALUATION | ||

|---|---|---|

| Motivations* | Donor Knowledge and Understanding of Risks* | Relationship with Transplant Candidate* |

| Repair relationship | Short and long term risk for surgery for donor* | Duration of relationship |

| Self-esteem | Short and long term risk for surgery for candidate* | Type of relationship and closeness |

| Complicated Bereavement | Alternative treatments for candidate* | Expectations for change in the relationship |

| Recognition and publicity | Feelings of obligation/desire for forgiveness | |

| Social Support | Donation Consistent with Past Beliefs/Behaviors | Motivation to Donate* |

| Caregiver for assistance and transportation | Donor on Driver’s license | Request from candidate or family |

| Long-term plans in case of complications | History of Volunteering* | Decision for order of evaluation |

| Family support of donation | Values, beliefs, lifestyle* | Consistent with values/beliefs/behaviors |

| *Health Behaviors | *Psychiatric History | Legal |

| *Smoking (duration, frequency, amount)* | DMS V Disorders/Symptoms | Incarcerations (reason, duration) |

| *Alcohol (duration, frequency, amount)* | Past History of Trauma/Abuse/Neglect | DUIs (number, years) |

| Activities of Daily Living | Outpatient treatment | Propagation/House arrest |

| *Recreational drugs (type, frequency, duration)* | Inpatient treatment | Past and Current legal problems (e.g., probation) |

| Coping Strategies for Stress | Suicide or Homicidal Ideation or Attempts | |

| Adherence to recommendations | Psychiatric Medications | |

| Psychosocial History* | Family History* | Financial Information |

| Born and Raised | Mother and father | Primary insurance |

| Citizenship/Language(s) | Other caregivers | Need for secondary insurance |

| Development issues | Siblings | Insurance for medications |

| Race/Ethnicity/Culture* | Marital Status | Risks for obtaining short/long term disability |

| Religion Beliefs and Practices* | Children | Prescription drug coverage |

| Losses and Recovery | Current caretaker | Health/life insurance cancellation/premiums* |

| Highest grade completed* | Other significant relationships | Employer’s understanding and compensation* |

| Learning problems and literacy | Identified caregiver post-surgery* | Employment status if complications occur |

| Occupation(s) | ||

| Military experience | ||

| Past Surgeries/Complications | ||

| Competency* | ||

| Housing and Transportation* | Understanding and Preparation for Surgery* | Power of Attorney/Living Will |

| Persons in household* | Short- and long-term risks for donor a | Medical decision maker |

| Transportation to and from hospital | Short- and long-term risks for candidate | Advanced directives |

| Post-donation housing | Expectations for recovery | Pressure/Coercion* |

| Caregiver and recipient’s caregiver | Alternative treatments for candidate | Assistance with living expenses/college |

| Barriers to caregiver | Past surgeries and experiences | Employee-Employer |

| Family or candidate pressure | ||

| Medical team | ||

| *Health Behaviors | Capacity to Make Autonomous Decisions | National Kidney Registry/Paired Exchange |

| *Smoking (duration, frequency, amount)* | Interview or formal testing if warranted | Understanding of process and potential problems |

| *Alcohol (duration, frequency, amount)* | Losses and Past Experience with Bereavement | |

| Activities of Daily Living | ||

| *Recreational drugs (type, frequency, duration)* | *Additional Evaluation/Testing or Intervention | *High Risk Behaviorsb |

| Coping Strategies for Stress | ||

According to UNOS policy 14.0

Public Health Service (2013)

There are high risk behaviors that may increase the risk for transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), or hepatitis C virus (HCV). A screening of these behaviors has recently been added to the donor evaluation. Each of the eleven criteria below reflect increased risk of all three pathogens as an aggregate, as there is overlap of associated risk, even though each factor does not convey risk from all pathogens equally (23). The six risk factors addressing sexual contact include in the definition of “had sex” referring to any method of sexual contact, including vaginal, anal, and oral contact. The eleven risk factors include: (1) a child who has been breastfed within the preceding 12 months and the mother is known to be infected with, or at increased risk for, HIV infection; (2) people who have injected drugs by intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous route for nonmedical reasons in the preceding 12 months; (3) people who have been in lockup, jail, prison, or a juvenile correctional facility for more than 72 consecutive hours in the preceding 12 months; (4) people who have been newly diagnosed with, or have been treated for, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, or genital ulcers in the preceding 12 months; (5) people who have had sex with a person known or suspected to have HIV, HBV, or HCV infection in the preceding 12 months; (6) Men who have had sex with men (MSM) in the preceding 12 months; (7) women who have had sex with a man with a history of MSM behavior in the preceding 12 months; (8) people who have had sex in exchange for money or drugs in the preceding 12 months; (9) people who have had sex with a person who had sex in exchange for money or drugs in the preceding 12 months; (10) people who have had sex with a person who injected drugs by intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous route for nonmedical reasons in the preceding 12 months; and (11) people who have been on hemodialysis in the preceding 12 months (23). If the living donor meets any of these high risk behaviors, the transplant recipient may need to be made aware of the potential risks involved prior to accepting the live donor transplant. If the donor is not willing to share this information with the transplant candidate, s/he may need to be declined from donation.

Education

The psychosocial evaluation includes not only a thorough interview with the donor to evaluate their suitability but also providing the donor with educational information. The evaluator provides information regarding financial resources, access to Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA), potential risks to health and life insurance, Advance Directives and Living Wills, financial responsibility for medication and other expenses after surgery. It is recommended that the health care professional completing the evaluation may provide the donor with information in writing as well as verbally. However, evaluation of the donors’ literacy level is recommended if s/he did not graduate from high school nor has a GED. If needed, the clinician may assist the donor in completing the necessary paperwork needed for financial assistance and/or FMLA.

Documentation

Since a large percentage of ILDA’s also perform the psychosocial evaluation, it has recently been recommended that the documentation for the psychosocial evaluation is separate from the ILDA evaluation (11). The documentation of psychosocial evaluation should be included in the potential donor’s medical record. The donor should be informed that the information shared will be placed in their medical record and is not protected as other mental health information. This may also be included in the informed consent for the donor evaluation. If the health care professional performing the psychosocial evaluation finds that the donor requires further testing (e.g., neuropsychological testing for competency) or intervention prior to donation (e.g., drug or alcohol rehabilitation) prior to surgery this must be documented in the medical record and the donor should be informed of the specific goals in order to be considered to be suitable for surgery. The recommendations should be provided verbally and in writing and the donor should have the information and option to follow up with questions as s/he pursues recommended intervention. The psychosocial evaluation should also include whether the donor was suitable for surgery or if there are contraindications for surgery (e.g., active substance abuse, poor adherence to medical recommendations, unable to be absent from work to recover).

Each transplant center must include in their policy how long the psychosocial evaluation is valid (e.g., 6 months or one year). The psychosocial evaluation must be performed again if the surgery had not occurred within the time period specific in the policy. It is recommended that the health care professional’s documentation includes written assurances that the donor is “of free will” and acknowledges that they have not engaged in risk behaviors according to the PHS (see above).

Specifics regarding the Psychosocial Evaluation of Non-Directed Donors and Donors Entering the National Kidney Registry

The number of emotionally and/or biologically unrelated donors increases each year (4–5). The psychosocial evaluation of non-directed, or altruistic, donors often receive more consideration and in depth evaluation particularly with regard to the motivations for donating and in the case of non-directed donors, issues of valuable consideration should be addressed carefully. It is recommended that the donor and potential candidate do not meet prior to surgery and there are inconsistent guidelines across transplant centers regarding whether the donor and candidate should meet after surgery even if both parties agree. Similarly, those donors who may be part of the National Kidney Registry (NKR) or other paired exchange programs may require additional evaluation and education secondary to the specific issues that occur with donors who are involved in these exchange programs. In the case of both non-directed donation, directed with little biological or emotional connection, and those involved in exchanges of kidneys, assessment of whether the donor is comfortable with media attention and their wishes should be addressed prior to the surgery as these types of surgeries have a greater likelihood of receiving media attention, particularly with large chains of donors and recipients.

Multidisciplinary Selection Committee and Donor Confidentiality

The health care professional that performs the psychosocial evaluation of the living donors is recommended to attend the multidisciplinary selection committee meeting to provide the results of their evaluation. The individual who performed the psychosocial evaluation may explain to the team that there are contraindications for the surgery and make recommendations for treatment. The health care provider providing the psychosocial evaluation may also confirms if the donor has a post-operative caregiver that will provide assistance and transportation; adequate financial resources to be out of work while recovering, and if recommendations for behavior change (e.g., smoking cessation) that will improve the outcomes of surgery.

Post-Decline and Post-Surgical Psychosocial Care

The team member performing the psychosocial evaluation should also have at least one contact with the potential donor after s/he has been declined from surgery although this is not mandated at this time. The reasons for being declined from surgery can range from a new diagnosis of cancer or less serious medical problems that require medical intervention. Issues related to paternity may also be discovered which may result in significant distress to a donor. Furthermore, the donor may be the transplant candidate’s only living donor option and s/he may experience distress or anticipatory grief as the candidate may die while waiting for a deceased organ. At this time, it is recommended that the health care professional(s) performing the psychosocial evaluation also follow up with the donor at least once after surgery. However, if the donor develops psychiatric symptoms (e.g., depression, panic attacks) after surgery; the recipient has complications or dies; or the donor experiences medical complications after surgery; it may be recommended that the social worker, psychologist, or psychiatrist evaluate the donor and continue to follow the donor for several weeks or months after surgery. If the donor resides far from the transplant center, referrals of a mental health provider in the donors’ community may be recommended.

The Independent Living Donor Advocate Evaluation

Goals and Timing of the ILDA Evaluation

The role of the ILDA has been continuously evolving since 2007 when the CMS published new conditions of participation for transplant centers and included this as a program requirement for those centers performing live donor transplants. Specifically, the identification of an ILDA or independent living donor advocate team to ensure the protection of the rights of living donors and prospective living donors became a requirement. In addition, it was recommended that the individual(s) must not be involved in the routine evaluation of transplant candidates. The living donor advocate assures the prospective living donor possesses no knowledge of the transplant candidate. The knowledge of this by the donor candidate promotes the notion that the ILDA is advocating for the rights and safety of the potential living donor and ensuring that they receive and understand the information necessary to make an informed decision that is in their best interest, and may not necessarily be in the best interest of the intended recipient.

It is the responsibility of the ILDA to represent, advocate, protect, and promote the best interests of the living donor. In order to effectively fulfill this role, the partnership between the ILDA and the living donor candidate must begin early in the screening and evaluation process. Transplant centers vary in their processes for prospective donors as some centers involve the living donor advocate early in the screening of prospective donors while other centers the ILDA meets the donor candidate during the face to face evaluation. However, a face to face or evaluation using telemedicine evaluation is recommended whenever possible. Some centers utilize two ILDAs to assess the donor during the evaluation and post-evaluation and come to an agreement with regard to their suitability. One of the roles of the ILDA is to explain to the donor the evaluation process and risks associated with the evaluation. Prior to proceeding with the evaluation, the donor candidate must understand these risks, be free to ask questions without fear of bias, and acknowledge that they may learn of medical conditions and/or unexpected results of paternity. It is recommended that the ILDA have a second contact after the initial evaluation to allow for a cooling off period, and determine if s/he would still like to proceed after learning of the medical, psychosocial, and financial risks of donation and determine if all the donors’ questions were answered. The ILDA should have contact before and after meeting with the nephrologists/hepatologists and surgeon as the ILDA’s role includes explaining the evaluation process to the donor as well as assessing the donors’ understanding of the risks which can only after the meeting with the physicians.

Health Care Professionals Performing the ILDA Evaluation and Education of Living Donors

Centers across the county utilize various professionals as ILDAs including social workers, physicians, psychologists, registered nurses, clergy, and ethicists to fulfill this requirement (11). From whichever discipline the ILDA represents, the role evolves around protecting and promoting the rights of the living donors. The ILDA ensures that the donor candidate understands the evaluation process and is informed of the medical, psychosocial, and financial risks related to living donation and all components necessary for informed consent, including knowledge and understanding of the surgical procedure and risks. In addition, the living donor must understand the benefit of and need for follow-up requirements post-donation and make the commitment to follow through with these medical appointments.

Components of the ILDA Evaluation

The components of the ILDA evaluation are outlined in Table 2. The highlights of some of the components of the evaluation are provided below and including the donor’s willingness and competence to donate; understanding the motivations of the donor to undergo surgery for another person; assessment of potential pressure or coercion; the donor’s understanding of the medical, psychosocial, and financial risks of donation; assessment of valuable consideration, the donor’s experience with prior surgeries or the health care system, and education of the donor.

Table 2.

| IDLA EVALUATION | |

|---|---|

| Willingness to Donate | Understanding of how health affects ability to donate |

| Competence to Donate | Donor may be declined to donate at any time |

| Motivations to Donate | Informed of Alternatives for the candidate |

| Informed Consent for the Surgery | Risk of candidate’s morbidity and mortality |

| Motivations to Donate | Competence to Donate |

| Informed Consent for the Surgery | Informed Consent |

| Pressure or Coercion | Valuable Consideration |

| Candidate or candidate’s family | Money |

| Medical team Self (internal obligation/guilt) | Intangible goods or services |

| Education | |

| NOTA Law | Evaluation Process |

| Long-term follow up care after surgery | Medical Risks |

| Right to withdraw from surgery | Psychosocial Risks |

| Medical Out | Financial Risks |

Willingness and Competence

The ILDA must determine if the donor is willing to donate and competent to make an informed decision. The donor’s willingness to donate may be evaluated in several ways including their participation in the evaluation, continued interest in surgery after a cooling off period, and ongoing demonstration of wanting to undergo surgery (e.g., completion of tests, return the medical teams phone contacts). Living donor candidates must be assured that their decision to donate is completely voluntary and that they may withdraw from the process and decline to donate at any point up until receiving anesthesia. Should the donor candidate decide not to proceed, the living donor advocate must identify any anticipated implications and dispel any fear that relationships with the transplant candidate, family members, or mutual friends will be negatively impacted. The donor candidate must understand that a decision not to proceed with donation is confidential and will not be shared without the consent of the donor (24). While some transplant centers provide a letter to the prospective donor simply stating that they are a non-candidate for living donation, others provide a “medical out” for the donor candidate. Although most ILDAs do not formally assess competency of the donor, under certain circumstances the ILDA may want to refer the donor candidate for a formal evaluation of competence such as in instances where the donor has a history of traumatic brain injury or a developmental disorder.

Donor Motivations

Identifying the motivating factors of the prospective donor early plays a key role in highlighting willingness to donate. These factors are often more clearly identifiable for biologically or emotionally related living donor candidates than they are when the non-related directed or non-directed or altruistic donor candidate would like to donate an organ. Related living donor candidates are often driven by a sense of family and feelings of love and protection. Non-related living donation often requires further exploration of identification of the donors’ motives such as a desire to contribute to society, or simply acting out of love and compassion. Relationships that also may require further examination include, but are not limited to; employee/employer, members of common organizations, faith community members, or those established via internet or through social media (e.g., Facebook). It is the role of the ILDA to initiate discussions that allow the prospective donor to identify and understand these influencing factors that may drive their desire to donate (25–26).

The ILDA evaluation assesses the process by which the donor candidate arrived at the decision to be evaluated for living donation. The living donor advocate identifies whether this is a related or non-related living donor candidate. The living donor advocate asks questions that will disclose the quality of the relationship, the circumstances surrounding the knowledge of the need for a transplant, and how they personally came to the decision to be evaluated for living donation (e.g., did the transplant candidate ask the donor, did the family request consideration of donation, did the donor volunteer). Discussion should include the prospective donor’s understanding of the donation process, including recovery time. It is important to determine if s/he is aware of others having been evaluated as potential living donors; the length of time the prospective donor considered and researched donation prior to coming in for evaluation, and whether or not the intended recipient is aware of the evaluation and their reaction.

Pressure or Coercion

Prospective donors have the explicit right to make a voluntary decision to move forward with the evaluation and/or act of living donation. Their decision must be free of pressure or coercion and undue influence from the transplant candidate, family members, and the medical team(s). The ILDA must specifically ask if the donor is feeling any pressure to donate and, if so, from whom. Signs that there may be coercion and pressure that lead to further investigation can include a reluctance to answer questions freely, displaying ambivalence toward living donation, the candidate or family member insisting to be present during the evaluation, or voicing past or present conflict with the intended recipient [2,3]. Although not always a contraindication, exploration of whether other persons in the donor’s family or friends oppose the surgery and the reasons why may be discussed. Issues such as withholding a place to live, support for college, and other types of pressure (e.g., loss of livelihood if employer) may not be as clear without careful exploration.

Understanding the Risks of Donation

Assessment of the donors’ understanding of the medical, psychosocial, and financial risks may need to be performed after the donor has met all team members who provide this type of education during the evaluation. The ILDA is also recommended to provide donors with an understanding of the evaluation process which occurs early in the donors’ visit to the transplant center and then later an understanding of these risks after s/he has met all of the members of the transplant team. After the evaluation all of the risks should be reviewed by the ILDA with the donor that is included in the informed consent at the respective ILDA’s transplant center to make certain the donor was explained each of the risks and has another opportunity to ask questions.

Valuable Consideration

When evaluating motivation, the ILDA must also assess for any signs of monetary/financial gain or valuable consideration as a result of living donation as defined by the NOTA law (27). The living donor advocate must be certain that the donor candidate understands the unlawfulness of receiving valuable consideration in exchange for an organ, and that they have a clear understanding of what is classified as valuable consideration. Expenses of travel, housing, and lost wages incurred by the donor while recovering from surgery are not considered valuable consideration; therefore living donors may be compensated for these expenses by the transplant candidate, the transplant candidate’s family, through fund raising, or from organizations that assist donors (e.g., Casey Fund, the National Living Donor Assistance Center). A plan should be in place for donors or candidates who may raise more money than is needed to cover the out of pocket expenses (e.g., limits on web-based fundraising sites, monies being transferred to recipient for long-term medical expenses).

Prior Experience with Surgery and Health Care

The fact that the operative procedure associated with living donation carries with it inherent risk and yet provides no medical benefit to the potential donor must be disclosed to as well as understood. Questions during the evaluation regarding the prospective donor’s past experience with hospitalizations or surgeries can provide the ILDA with insight into fears and concerns the donor candidate may have regarding the donation. Discussion of the potential that the transplanted kidney may be rejected or that the candidate may die during or after the surgery is an important tool in assessing coping mechanisms. The risk to the donated kidney related to recipient compliance to the medical regimen as well as the intended recipient’s morbidity and mortality are also topics for discussion during the ILDA evaluation. Understanding the donor’s experience with loss may also be assessed to facilitate how they may manage if the recipient passes away during or after surgery.

Education of the Living Donor by the ILDA

The ILDA not only evaluates the donor but also provides education. One of the areas in which the ILDA is recommended to educate the donor is on the evaluation process including which they will be meeting with, the time line with regard to evaluation to being informed that they are a candidate for surgery or are being declined, and approximate time to having surgery. The ILDA also informs the donor that the testing that will be performed and that the medical evaluation may uncover a health condition that the donor candidate was previously unaware of or a medical condition that results in the requirement of a health care professional reporting to governmental health care agencies. The evaluation could uncover a benign finding or it could be as harmful as a potentially life threatening condition such as cancer or HIV. Prospective donors must be cognizant of this possibility, their readiness for this information, and the potential impact it may have on their future daily living (i.e., pre-diabetic, impaired renal function).

All potential donors should be informed of alternatives for the transplant candidate other than living donation including a deceased donor organ or other potential living donors. The ILDA must assess the prospective donor’s knowledge about whether or not the intended recipient is on the deceased donor waitlist, as well as their knowledge about the potential contributing factors to the transplant candidate’s end stage organ failure and in some cases the chance the transplant candidate may need another transplant or may become involved in behaviors that result in the need for another transplant (e.g., non-adherence to immunosuppressive medications, alcohol abuse disorder).

The ILDA may encourage the donor to discuss with their spouse or intimate partner support that donation carries with it an increased risk of mortality and morbidity, in addition to potential stressors related to childcare issues, care of pets, and assistance with transportation and post-surgery care, particularly if there are complications. If the donor candidate does not have in place a power of attorney and living will, the ILDA may make recommendations to have these completed before surgery.

Both future and current household finances can be impacted by living donation. The ILDA may ask questions about the employer’s knowledge and reaction regarding the potential living donation; the donor candidate’s knowledge about time off work policies; and any anticipated effect on employment or occupation with the possibility of complications requiring extended hospitalizations and time away from work. By ensuring that the potential donor understands and fully evaluates the impact that living donation may have on the spouse and family members, the living donor advocate is protecting and promoting the best interest of the potential living donor [8].

The ILDA may also supplement the verbal information about the medical, psychosocial, and financial risks with written materials from a reputable source (e.g., UNOS). In addition, a written copy of the NOTA law describing valuable consideration should be provided by the ILDA and in some cases, the ILDA may have the donor sign their acknowledgement of receiving the information and having a chance to ask questions. For donors who may have concerns about receiving compensation, the signing of the document may come with hesitation. Finally, the ILDA may want to provide a document stating they understand the recommendations for a minimum of two years of follow-up with a physical exam and laboratory tests. Information regarding where these tests can be performed, the tests, as well as a fax number where they can have the test information faxed to if they do not have the follow up completed at the transplant center.

Documentation and Donor Confidentiality

The ILDA is to document all meetings and discussions, face to face or by phone, with the living donor candidate to be included in the medical record. Specifically, the prospective donor’s receipt of information necessary for informed consent as defined by CMS, the evaluation process as it relates to living donation, the surgical procedure itself, as well as the benefit and need for follow-up post donation. It is also important to include the donor candidate’s understanding of the grievance process specific to the transplant center related to non-candidacy determination (28). It is recommended that this documentation include receipt of information related to the NOTA law; understanding of medical, psychosocial, and financial risks; and motivating factors for living donation (i.e. absence of coercion or pressure), and willingness to engage in the two year follow up recommended by UNOS. The ILDA should include the willingness of the donor candidate to proceed with evaluation and living donation or the decision not to move forward, including how to facilitate this so as not to impact any relationships that may be affected.

Donor confidentiality, as defined during the initial evaluation meeting, is maintained and protected by the ILDA. Information is only shared with and among the members of the multidisciplinary team as it relates to living donation. Specific information related to non-candidacy of living donors is not shared outside of the team members unless authorized or requested by the living donor candidate. The ILDAs who place the details of their evaluation in the medical record, should make the donor aware of this and that other health care providers may view the ILDA’s notes and for those donors who do not proceed with surgery the increased chance of breaching this confidentiality may occur with detailed notes in the medical record. The donor should be made aware of this through the informed consent process. Alternatively, the IDLA can include a brief note in the medical chart stating that the ILDA met with, evaluated, and provided educational information to the donor; and include more detailed notes in a private confidential location.

Non-Directed and Paired Exchange Programs

As with the psychosocial evaluation, the ILDA may want to provide more detailed assessment and education of donors who will be donating to a non-biological or emotionally related transplant candidate. Also, some donors prefer not to be involved in the paired exchange program. The ILDA should evaluate their understanding of the process and the donor’s concerns to assure that their decision is not based on misperceptions of the paired exchange program.

Post Evaluation Contact

Since the ILDA is recommended to provide donors with the understanding and risks of the evaluation process the ILDA often meets with the donor during the initial evaluation. The ILDA is also responsible for assessing the donors’ understanding of the risks of donation which can only be accomplished after the donor has met with the entire transplant team. Therefore, it is recommended that the ILDA have a second contact after the donor undergoes the face to face evaluation to assess the donor’s understanding of the risks of surgery. These include, but are not limited to; complications leading to another surgery; the impact on lifestyle; injury to the spleen, appendix, or pancreas; the loss of kidney function (in the case of kidney donation); the need for a transplant; scars, pain, fatigue, abdominal bloating, nausea, constipation, infection, excessive bleeding requiring a blood transfusion, blood clot; damage to nerves; sores from position during surgery; burning; damage to arteries or veins; burns from equipment; pneumonia; heart attack or stroke; and the risk of death (7).

The ILDA evaluation must also include the potential donor’s understanding of the psychosocial risks related to living donation. Potential psychosocial risks can include body image concerns; depression; anxiety; emotional distress; feelings of guilt; impact on lifestyle; and feelings of loss. There is the possibility that although living donation occurs, the transplant recipient may experience rejection of the organ, the need for re-transplantation, recurrence of disease, or even death. For informed decision making and consent to occur, the prospective donor must have an understanding of these risks, as well as the potential impact on the donor’s lifestyle as it relates to all risks associated with living donation (7). The donor candidate also needs to consider the psychological effects that they may experience related to the identification of a future health problem during the medical evaluation. In addition, should the multidisciplinary team deem the potential donor a non-candidate, this may have a negative emotional impact and they must be made aware of this possibility.

Understanding the financial risks is important and should be discussed with the living donor candidate. Living donors may incur personal costs that may not be reimbursed such as: transportation, flight and/or gas; lodging; meal; and child care. Household income may be impacted by time off work, the possible loss of employment, or the ability to obtain future employment. Additionally, health care conditions experienced by living donors following donation may not be covered by the recipient’s insurance. The living donor advocate must assure that the donor candidate is cognizant of all of these risks (7).

The ILDA should ask the potential donor if there is a possibility of financial hardship related to these financial risks should they proceed with donation. A thorough evaluation identifies those donors that may be at a higher financial risk. Prospective donors must also be aware of the potential for increased premium rates, or even denial, in relation to health, disability, and/or life insurance following living donation or evaluation [8]. When the donor, or the recipient, experiences complications or death; these financial risks are even greater and should be discussed with the donor.

Multidisciplinary Selection Committee Meeting

Although not consistent across transplant centers, the ILDA may attend the living donor portion of the selection committee meeting (11). Most multidisciplinary meetings include presentation of both the prospective donors and transplant candidates so the ILDA optimally would only be present for the discussion of living donor presentations (11). To maintain confidentiality, the ILDA may simply state whether there was a contraindication for living donation surgery or not from the ILDA perspective. Although the ILDA may want to provide information regarding the donor if there are contraindications for proceeding, the risk increases with regard to the information being disclosed to the transplant candidate if provided during the selection committee meeting despite HIPAA laws that each health care professional attending the meeting should adhere to with regard to the information presented.

Post-Decline or Post-Surgery Care

Post-operative recovery and discharge planning are in integral component of the initial evaluation. The impact of recovery time, plans for post-surgical assistance with daily activities, and driving assistance should be assessed. In addition, should recovery take longer than anticipated, there may be a need for additional support and resources (30). If the donor or recipient has complications or the recipient passes away during or after surgery, the ILDA may follow the donor for an extended period of time to assess ongoing distress and care. If needed, referrals to mental health professionals or patient relations within the medical center.

Living donor candidates must understand the importance of and commit to post-surgical follow up testing as coordinated by the recipient transplant center. Transplant centers must disclose to the donor candidate whom is responsible for the cost of the follow-up care. The ILDA must emphasize the importance and make certain that the donor candidate understands the government requirement that transplant centers report health information on living donors at 1 week post-discharge, 1 and 3-months (for living liver donors), 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years post-donation. Living donors should expect to be contacted by the transplant center regarding their current health status at these intervals and understand that this is the best method identified for collecting information on the health implications related to living donation (29). The ILDA may provide verbal and written information to the donor candidate regarding the required follow up by UNOS and CMS. It is also recommended that donors continue to have the same test performed annually for the rest of their lives to be able to detect problems early and provide medical intervention if warranted. The ILDA can gain insight into past and present behaviors by asking questions regarding current health care practices and lifestyle to identify if there is a need for further education. Optimally, if the resources were unlimited, the ILDA could continue to follow the donor for several years post-donation to assess their health and psychosocial functioning but this is not feasible at many centers due to time and financial constraints.

If the prospective donor is deemed a non-candidate for living donation by the multidisciplinary selection committee, a post-decline contact by the ILDA is recommended to determine if there are additional questions to be answered or information required to assist the patient with acceptance and understanding of the reasons for decline. Further, the ILDA can address any barriers to evaluation or treatment of the new diagnosis provided by the transplant team.

Limitations and Future Directions

Important limitations of this paper may include biases of the disciplines of the authors which included social workers, nurses, and psychologists. The biases may also be influenced by each of their discipline, experience with donor evaluations, their own transplant center’s operations, and experience with CMS and UNOS visits and audits. Furthermore, the recommendations provided here reflect the current guidelines and recommendations by UNOS and CMS. As with transplantation, the UNOS and CMS guidelines and regulations continually evolve. As a result, updates to the psychosocial and ILDA evaluation process will also evolve. Finally, due to the different disciplines involved in the psychosocial and ILDA evaluations and differences with regard to state laws; at this time no instruments or standardized or structured interview has been developed to assess the areas described above. The development of a structured evaluation process and screening tools to be used by health care professionals performing the psychosocial and/or ILDA evaluations may be recommended to improve consistency across transplant centers.

Contributor Information

Dianne LaPointe Rudow, Email: Dianne.LaPointeRudow@mountsinai.org, Recanati Miller Transplant Institute The Mount Sinai Medical Center One Gustave L. Levy Place; Box 1104, New York, NY 10029 212 659-9309.

Kathleen Swartz, Email: Kathleen.swartz@beautmont.edu, Department of Trauma Services, Beaumont Heath System, 3601 West 13 Mile Rd., Royal Oak, MI 4807 248-898-5024.

Chelsea Phillips, Email: steeljl@upmc.edu, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Surgery, 3471 Fifth Avenue, Pittsburgh PA 15213, 412-692-2041.

Jennifer Hollenberger, Email: Hollenbergerjc@upmc.edu, Department of Collaborative Care Management, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, 200 Lothrop Street, Pittsburgh PA 15213, 412 647-3255.

Taylor Schmick, Email: taylor.schmick@gmail.com, Department of Collaborative Care Management, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, 3471 Fifth Avenue, Pittsburgh PA 15213.

Jennifer Steel, Email: steeljl@upmc.edu, Department of Surgery, Psychiatry and Psychology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, 3471 Fifth Avenue, Pittsburgh PA 15213, 412-692-2041.

References

- 1.http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/

- 2.Murphy Blake D, Zuker Ronald M, Borschel Gregory H. Vascularized composite allotransplantation: An update on medical and surgical progress and remaining challenges. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive, and Aesthetic Surgeons. 2013;66(11):1449. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.06.037. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23867239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray JE, Merrill JP, Harrison JH. Kidney transplantation between seven pairs of identical twins. Ann Surg. 1958;148:343–359. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195809000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U S Renal Data System USRDS. 2013 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, National Institutes of Health. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Purnell TS, Auguste P, Crews DC, et al. Comparison of life participation activities among adults treated by hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:953–73. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibrahim HN, Foley R, Tan L, et al. Long term consequences of kidney donation. New England J Medicine. 2009;360(5):459–69. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segev DL, Muzzaale AD, Caffo BS, et al. Perioperative mortality and long term survival following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2010;303(10):959–966. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clemens KK, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Parikh CR, Yang RC, Karley ML, Boudville N, et al. Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network Psychosocial health of living kidney donors: A systematic review. American J of Transplantation. 2006;6:2965–2977. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaPointe Rudow D, Charlton M, Sanchez C, Chang S, Serur D, Brown RS. Kidney and liver living donors: a comparison of experiences. Progress in Transplantation. 2005;15(2):185–191. doi: 10.1177/152692480501500213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.10 Gross CR, Messersmith EE, Hong BA, Jowsey SG, Jacobs C, Gillespie BW, Taler SJ, Matas AJ, Leichtman A, Merion R, Ibrahim HN, the RELIVE Study Group Health-Related Quality of Life in Kidney Donors From the Last Five Decades: results from the RELIVE study. American Journal of Transplantation. 2013;13:2924–2934. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jowsey SG, Jacobs C, Gross CR, Hong BA, Messersmith EE, Gillespie BW, Beebe TJ, Kew C, Matas A, Yusen RD, Hill-Callahan M, Odim J, Taler SJ, the RELIVE Study Group Emotional Well-Being of Living Kidney Donors: Findings from the RELIVE Study. American Journal of Transplantation. 2014;14:2535–2544. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emre S. Living –donor Liver transplantation in children. Pediatric Transplantation. 2002;6:43–46. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3046.2002.1r072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olthoff KM, Merion RM, Ghobrial RM, et al. A2ALL Study Group Outcomes of 385 adult-to-adult living donor liver transplant recipients: a report from the A2ALL Consortium. Ann Surg. 2005;242(3):314–23. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000179646.37145.ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freise CE, Gillespie BW, Koffron AJ, Lok AS, Puett TL, Emond JC, Fair JH, Fisher RA, Olthoff KM, Trotter JF, Ghobrial RM, Everhart JE, A@ALL Study Group Recipient morbidity after living and deceased donor liver transplantation: findings from the A2AKK retrospective cohort study. American Journal of Transplantation. 2008;12(12):2569–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oltoff KM, Abecassis MM, Emond JC, Kam I, Merion RM, Gillespie BW, Tong L, the A2ALL Study group Outcomes of adult to adult living donor transplantation: Comparison of the adult-to adult living donor liver transplantation cohort study and national experience. Liver Transplantation. 2011;17:789–797. doi: 10.1002/lt.22288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abecasis MM, Fisher RA, Olthoff KM, Freise CE, Rodrigo DR, Samstein B, Kam I, Merion RM, A2ALL Study Group Complications of living donor hepatic lobectomy–a comprehensive report. American Journal of Transplantation. 2012;12(5):1208–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ladner DP, Dew MA, Forney S, Gillespie BW, Brown RS, Merion RM, Freise CE, Hayashi PH, Hong JC, Ashworth A, Berg CL, Burton JR, Shaked A, Butt Z. Long-term quality of life after liver donation in the adult to adult living donor livers transplantation cohort study (A2ALL) Journal of Hepatology. 2015;62:346–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim-Schluger L, Florman SS, Schiano T, et al. Quality of Life after lobectomy for adult liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;73(10):1593–1597. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200205270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abecassis M, Adams M, Adams P, Arnold RM, Atkins CR, Barr ML, Bennett WM, Bia M, Briscoe DM, Burdick J, Corry RJ, Davis J, Delmonico FL, Gaston RS, Harmon W, Jacobs CL, Kahn J, Leichtman A, Miller C, Moss D, Newmann JM, Rosen LS, Siminoff L, Spital A, Starnes VA, Thomas C, Tyler LS, Williams L, Wright FH, Youngner S, Liver Organ Donor Consensus Group Consensus statement on the live organ donor. JAMA. 2000 Dec 13;284(22):2919–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) OPTN/SRTR 2012 Annual Data Report. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medicare Program. Hospital Conditions of Participation: Requirements for Approval and Re-Approval of Transplant Centers to Perform Organ Transplants; Final Rule. Federal Register. 2007;72(61) www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-certification/CertificationandComplicance/downloads/trasnplantfinal.pdf Found online December 11, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CMS Survey and Certification Letter: Organ Transplant Interpretive Guidelines. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/downloads/SCLetter08-25.pdf Found online December 11, 2014.

- 23.Organ Transplantation and Procurement Network, Policy 14, Living Donation. http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/ContentDocuments/OPTN Policies.pdf Found online December 11, 2014.

- 24.Steel JL, Dunlavy A, Friday M, Kingsley K, Brower D, Unruh M, Tan H, Shapiro R, Peltz M, Hardoby M, McCloskey C, Sturdevant M, Humar A. A national survey of independent living donor advocates: the need for practice guidelines. Am J Transplant. 2012 Aug;12(8):2141–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04062.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hays RE, LaPointe Rudow D, Dew MA, Taler SJ, Spicer H, Mandelbrot DA. The Independent Living Donor Advocate: A Guidance Document from the American Society of Transplantation’s Living Donor Community of Practice. American Journal of Transplantation. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13001. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steel JL, Dunlavy A, Friday M, Kingsley K, Brower D, Unruh M, Tan H, Shapiro R, Peltz M, Hardoby M, McCloskey C, Sturdevant M, Humar A. The development of practice guidelines for ILDAs. Clinical Transplantation. 2013;27(2):178–184. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Organ Transplant Act, Public Law 98-507. 1984 Oct 19; Title III Sec. http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/ContentDocuments/Guidance_InformedConsentLiving_Donors.pdf. [PubMed]

- 28.Seem DL, Lee I, Umscheid CA, Kuehnert MJ. Public Health Reports. 2013;128(4) doi: 10.1177/003335491312800403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Federal Register. 2007 Mar 30;72(61) Section 482.98(d) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]