Abstract

Using the parent-into-F1 model of induced lupus and (C57Bl/6xDBA2) F1 mice as hosts, we compared the inherent lupus-inducing properties of the two parental strain CD4 T cells. To control for donor CD4 recognition of alloantigen, we used H-2d identical DBA/2 and B10.D2 donor T cells. We demonstrate that these two normal, non-lupus prone parental strains exhibit two different T cell activation pathways in vivo. B10.D2 CD4 T cells induce a strong Th1/CMI pathway characterized by IL-2/IFN-g expression, help for CD8 CTL, skewing of DC subsets towards CD8a DC, coupled with reduced CD4Tfh cells and transient B cell help. By contrast, DBA/2 CD4 T cells exhibit a reciprocal, lupus-inducing pathway characterized by poor IL-2/IFN-g expression, poor help for CD8 CTL, skewing of DC subsets towards pDC coupled with greater CD4 Tfh cells, prolonged B cell activation, autoantibody formation, and lupus-like renal disease. Additionally, two distinct in vivo splenic gene expression signatures were induced. In vitro analysis of TCR signaling revealed defective DBA CD4 T cell induction of NF-κB, reduced degradation of IκBα and increased expression of the NF-κB regulator A20. Thus, attenuated NF-κB signaling may lead to diminished IL-2 production by DBA CD4 T cells. These results indicate that intrinsic differences in donor CD4 IL-2 production and subsequent immune skewing could contribute to lupus susceptibility in humans. Therapeutic efforts to skew immune function away from excessive help for B cells and towards help for CTL may be beneficial.

Keywords: graft-vs.-host disease, T cells, systemic lupus erythematosus, cytokines

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus) is an immune mediated, multi-system disease characterized by pathogenic autoantibodies against nuclear antigens (1). CD4 T cells are necessary and sufficient for lupus induction and are central in driving B cell production of autoantibodies in human and murine lupus. CD4 T follicular helper (Tfh) cells provide help (e.g., IL-21) to autoreactive B cells in the germinal center (GC) (2, 3) and the resulting pathogenic IgG autoantibodies exhibit the hallmarks of a normal T cell driven ag driven response e.g., class switching, somatic mutation and affinity maturation (4–8). Disease expression is modified by genetic, hormonal and environmental factors (9). A major gap in our knowledge is the mechanism by which T cell tolerance is lost and lupus ensues.

A useful model for studying the role of ag-specific T cells in lupus pathogenesis is the parent-into-F1 (p→F1) model of chronic graft-vs.-host disease (cGVHD) (reviewed in (10) in which an a loss of T cell tolerance is experimentally induced in normal mice and lupus ensues. Following the transfer of homozygous parental strain CD4 T cells into unirradiated semi-allogeneic non lupus-prone F1 mice, donor CD4 T cells recognize host allogeneic MHC II bearing cells resulting in the expansion of host DC, cognate help to B cells, autoantibody production and a lupus-like phenotype. Co-transfer of both parental CD4 and CD8 T cells results in an additional phase of donor CD4 help for donor CD8 T cells specific for host allogeneic MHC I, which then mature into CTL effectors and eliminate host lymphocytes. Thus, a selective loss of CD4 T cell tolerance results in an autoimmune, stimulatory, lupus-like phenotype. In contrast, a loss of both CD4 and CD8 T cell tolerance results in an acute GVHD phenotype manifested by a cytotoxic T cell (CTL) mediated immune deficiency (similar to human acute GVHD) that aborts the progression to lupus-like disease.

Interestingly, the degree of similarity between CD4 driven chronic GVHD in this model and human lupus varies with the donor and host strains used. Host genetics contribute to lupus severity in chronic GVHD (11). However, a role for donor strain genetics has not been fully evaluated. Studies using the B6D2F1 (BDF1) strain as host are consistent with this possibility. Specifically, transfer of parental strain DBA/2 (DBA) splenocytes into BDF1 mice induces a disease that strongly resembles human lupus, consisting of: 1) lupus-specific autoantibodies (anti-dsDNA, anti-PARP); 2) lupus-like renal disease progressing to nephrotic syndrome, 3) lupus-like Ig and C’ deposition in the skin, 4) positive Coombs test and 5) a female predilection (10, 12–16). As with human lupus, organ specific autoantibodies are not observed in chronic GVHD mice (15). By contrast, chronic GVHD induced in BDF1 hosts using the opposite parent i.e. C57BL/6 (B6) CD4 T cells results in transient CD4 T cell driven B cell hyperactivity with mild renal disease without sex differences (17). A similar mild transient lupus is seen with B6 donors transferred into MHC disparate non-F1 hosts (i.e. B6→Bm12) (16) suggesting that B6 CD4 T cells inherently induce only mild lupus.

Similarly, acute GVHD in BDF1 mice exhibits donor strain variability. Transfer of unfractionated B6 donor splenocytes into BDF1 mice (B6→F1) induces a strong Th1/CMI response at days 7–10 (10, 18–20) as evidenced by: 1) significant expansion of donor CD8 T cells with effector phenotype (pfp+, GrB+); 2) expansion of CTL-promoting CD11c+ DC; and 3) a 2–3 fold log increase in serum IFN-g. Engrafted B6 donor CD8 effector CTL are specific for host MHC I (H-2d) and use both pfp and FasL pathways to eliminate host lymphocytes. Host B cells are highly susceptible to elimination and by two weeks are profoundly reduced (~10% of control F1). By contrast, transfer of unfractionated DBA splenocytes into BDF1 mice (DBA→F1) is associated with a failure of donor DBA CD8 CTL maturation and of host CD11c DC expansion coupled with only modest elevations of serum IFN-g. In the absence of donor CD8 CTL effectors, host B cells are significantly expanded (~150–200% of control F1) by day 14 due to donor CD4 T cell cognate help to F1 B cells following recognition of host allogeneic MHC II (I-Ab)(10, 18–20).

Together, these observations support the idea that B6 and DBA CD4 T cells exhibit strain differences in their lupus-inducing proclivity, and that this difference may be reciprocally related to their ability to help CD8 CTL. To further explore this possibility, we compared the intrinsic CD8 promoting vs. lupus promoting properties of C57 black background or DBA background CD4 T cells. Our results indicate that these two otherwise normal (non-lupus prone) donor strains induce two completely different activation pathways consisting of either: a) a strong Th1/CMI promoting pathway characterized by strong help for CD8 CTL and transient help for B cells; or b) a lupus pathway characterized by a poor Th1/CMI response and poor help for CD8 CTL but strong and sustained help for B cells. These distinct phenotypic outcomes may be functionally related to inherent differences in TCR signaling pathways that drive IL-2 production in CD4 T cells. In particular, DBA T cells exhibit reduced TCR activation of NF-κB, which may be due to increased expression of the NF-κB modulator, A20, in TCR-stimulated DBA T cells.

Materials and Methods

Mice

6–8 week old female DBA/2J (H-2d), C57BL/6 J(H-2b), B10.D2-Hc0 H2d H2-T18c/oSnJ (B10.D2) (H-2d) donor mice and female B6D2F1J (BDF1) (H-2b/d) recipient host mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All animal procedures were pre-approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences.

Induction of GVHD

Single cell suspensions of donor strain splenocytes were prepared as described (21) and transferred into age matched BDF1 hosts by tail vein injection. The percentages of donor CD4 and CD8 T cells populations were analyzed by flow cytometry and donor inoculum adjusted prior to transfer to achieve the desired amount of donor CD4 and CD8 T cells as indicated in the text and/or respective figure legends. In some experiments, acute GVHD was induced using purified donor T cell subsets achieved through negative isolation using Dynal mouse CD4 or CD8 negative isolation kits (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) which deplete B cells, NK cells, monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, granulocytes, platelets, erythrocytes and either CD8 or CD4 respectively. Purity was confirmed by flow cytometry and was typically > 95%.

Host NK depletion

F1 mice were depleted of host NK cells as previously described (22). Briefly, mice received 200 µg of anti-NK1.1 mAb (PK136, Biolegend, San Diego, CA) i.p. 2 days prior to and 2 days following donor cell transfer. At day 7, splenic host NK1.1+, asialo-GM1+ cells in untreated mice averaged .3 ×106 but were below the limits of detection in anti-NK1.1 treated mice.

Flow cytometric analysis

Spleen cells were first incubated with anti-murine Fcγ receptor II/III mAb, 2.4G2 for 10 min and then stained with saturating concentrations of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated, APC-conjugated, biotin-conjugated, PE-conjugated, FITC-conjugated, PerCPCy5.5-conjugated, Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated and Pacific Blue-conjugated mAb against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, B220, H2-Kb, I-Ab, H-2Kd, I-Ad, CD11b and CD11c, CD44, CD62L, CXCR5, ICOS, PD1, CCR7, KLRG-1, GL-7 and mPDCA purchased from either BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA), BioLegend (San Diego, CA), eBioscience (San Diego, CA), or Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Biotinylated primary mAb were detected using PE-Texas Red-streptavidin (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cells were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde before reading.

Ex vivo intracellular staining for perforin (pfp), granzyme B (GrB), IFN-g, TNF and IL-2 were performed using antibodies and reagents purchased from BD Biosciences (San - Jose, CA) or Biolegend (San Diego, CA) and staining performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Importantly, as previously described (23) there was no in vitro re-stimulation or use of Golgi blocking agents. Following completion of the staining protocol, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry immediately. For donor cell division studies, CellTrace™ CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit was used for in vivo labeling of cells to trace multiple generations using dye dilution by flow cytometry. Donor cells were labeled according to the manufacturer’s instructions prior to transfer and host splenocytes analyzed 3 and 4 later by flow cytometry and ModFit (Verity Software). Intracellular staining for KI-67 was performed using PE mouse anti-human KI-67 set from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) and the Foxp3 Buffer Staining set from eBioscience (San Diego, CA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were permeabilized overnight in fixation/permeabilization solution, then washed in permeabilization buffer, stained with PE-conjugated mouse anti-human Ki-67 in permeabilization buffer for 30 minutes, washed, then analyzed by flow cytometry immediately.

Multi-color flow cytometric analyses were performed using a BD LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Gating strategy: lymphocytes were gated by forward and side scatter and fluorescence data were collected for a minimum of 10,000 gated cells. Studies of donor T cells were performed on a minimum of 5,000 cells collected using a lymphocyte gate that was positive for CD4 or CD8 and negative for MHC class I of the uninjected parent (H-2Kd negative). B cells were gated as positive for B220 and either positive (host origin) or negative (donor origin) for MHC Class II of the uninjected parent (I-Ad). Short lived effector CD8 CTL (SLEC) were assessed as KRLG-1 positive, CCR7 negative gated donor CD8 T cells. Host DC and macrophages were identified as I-Ad positive and CD11c or CD11b positive respectively using a broad forward and side scatter gate. In Fig. 7, DC were further gated as CD3/CD19 negative, CD11c positive and either CD8a positive or mPDCA positive.

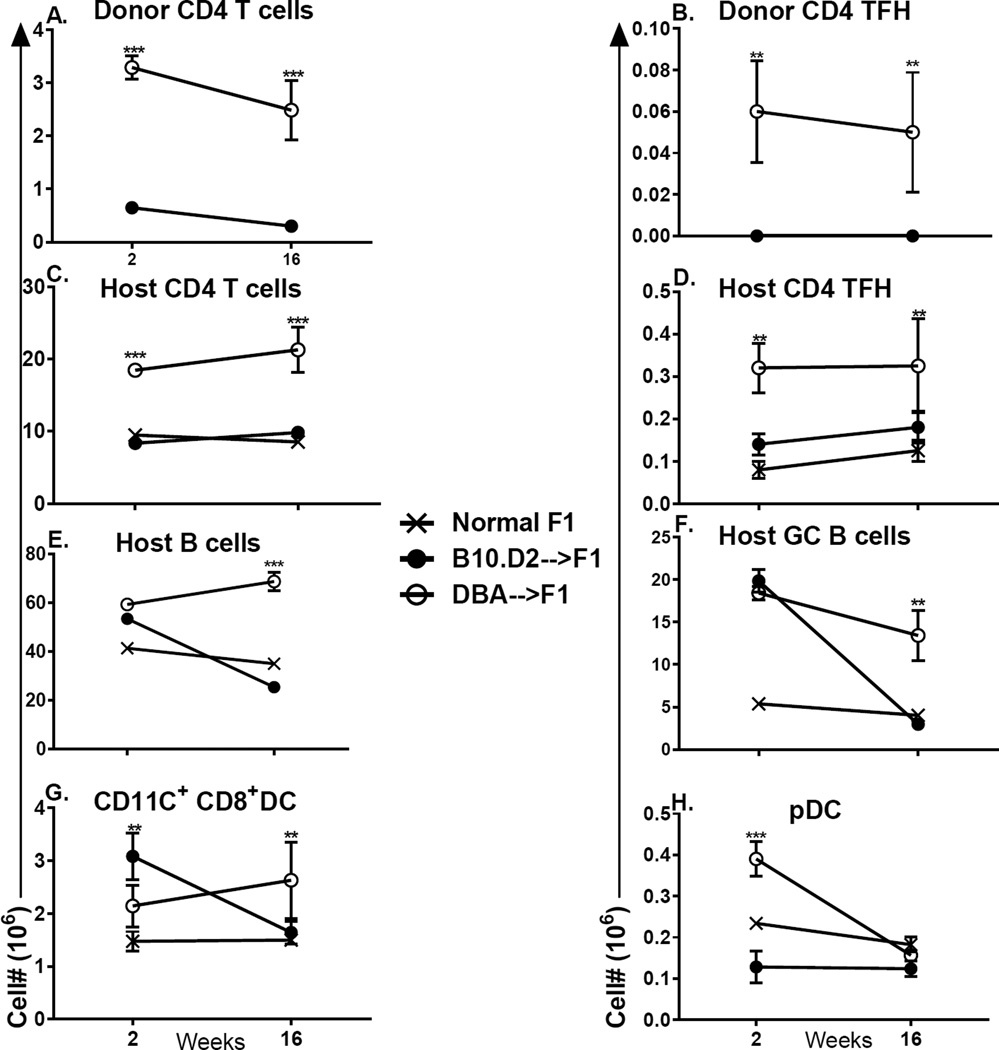

Fig. 7. Purified DBA CD4 T cells induce greater lupus-like parameters than do purified B10.D2 CD4 T cells.

F1 mice received 15 × 106 CD4 T cells negatively isolated from either DBA or B10.D2 donor spleens. In two separate experiments, mice were evaluated at either week 2 or week 16 for: (A) donor CD4 T cells (total); (B) donor CD4 Tfh cells (CXCR5+, PD-1+); (C) host CD4 T cells (total); (D) host CD4 Tfh cells; (E) host B cells (total); (F) host GC B cells (GL-7+); (G) host CD8a+, CD11c+ DC; (H) host pDC. Values represent group mean ±SE. n= 3– 5/group for week 2 and 5/group week 16.

Cytokine Expression by Real Time PCR

Real time PCR was performed as described (21). Briefly, splenocytes (1 × 107) were homogenized in 1 ml of RNA-STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX). cDNA was synthesized from mRNA using TaqMan® Reverse Transcription Reagents kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Real-time PCR was performed using pre-made primers and probes from TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays and TaqMan® Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) for the following targets: IFN-g, IL-10, IL-2, IL-21, IL-6, IL-4, OAS, MX-1 and IP10 with 18s rRNA as an internal control. The calculation of relative gene expression differences was done by comparative 2−ΔΔCT method. The result was expressed as fold change in the experimental groups compared to uninjected B6D2F1 control.

In vitro IL-2 studies

For studies using unfractionated splenocytes, B6 and DBA mice were tested individually (n=3–4/group). Splenocytes were first examined by flow cytometry for CD4 T cell percentage and 0.8 × 106 CD4 T cells (4–5 × 106 splenocytes) in 24 well flat bottom plates and stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb (0.25 µg/well) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). In a pilot experiment we observed that doses of either 0.25 µg or 0.50 µg of anti-CD3 gave roughly equivalent IL-2 responses for B6, DBA, MRL/+ and MRL/lpr splenocytes (data not shown). For studies of purified cells, CD4 T cells were purified by negative isolation using Dynal mouse beads as described above from pooled age and sex matched B6 or DBA donors, plated 4 ×106/well and stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 (0.5 µg/ml)(Biolegend, San Diego, CA). Purity of CD4 T cells was 98.5%. For both studies, supernatants were harvested at 48 hours and IL-2 content determined by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and arbitrary units calculated from a standard curve using the TITRI program as described (21). From separate wells, cells were harvested at 48 hours and assessed for IL-2 mRNA by RT-PCR as described above. Purified CD4 T cells were also examined for intracellular expression of IL-2 and for Foxp3 as described above.

Splenic gene expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated from individual subjects using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) after immediate stabilization of RNA in spleen tissue using RNAlater Reagent (Qiagen). Total RNA integrity was assessed using Experion RNA HighSens Chips on an Experion Automated Electrophoresis Station (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Samples with RNA integrity > 8.0 were labeled using the TotalPrep RNA Labeling Kit (Ambion, Grand Island, NY) before hybridization MouseRef-8 v2.0 Expression BeadChips (Illumina, San Diego, CA) and imaging on an iScan Microarray Scanner (Illuina) at the University of Chicago Genomics Core. Raw data output was generated from images using the GEX module of GenomeStudio (Illumina). Raw data was pre-processed by offset background correction and quantile normalization. Non-accurately detected BeadArray features were removed from pre-processed data for features with a detection p-value > 0.1 in at least 7% of subjects in all experimental groups. Differentially expressed transcripts were identified in the GenePattern 3.8 genomics analysis platform using the Comparative Marker Selection module (Broad Institute, MIT) (24, 25).

Intracellular Signaling studies

CD4 T cells were purified from DBA/2 and C57BL/6 mice using a negative isolation kit (Invitrogen). T cells were stimulated by plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28 for the indicated times, followed by harvest and preparation of whole cell lysates, as previously described (26–28). Lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with antibodies for IκBα, A20 and GAPDH.

Serological studies

Mice were bled at the times indicated and sera tested by ELISA for the presence of IgG antibodies to calf thymus DNA (Sigma-Aldrich, Atlanta, GA) as described (21)

Urine Protein

Urine protein was quantitated by dipstick (Albustix, Bayer Pittsburgh, PA).

Kidney Histopathology

Kidneys were processed, stained with periodic acid-Shiff stains and analyzed as previously described (12)

Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons (t test and Anova) were performed using Prism 5.0 (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

I. Results following transfer of unfractioned donor splenocytes

Defective in vivo Th1 cytokine expression by DBA T cells

To determine the mechanisms responsible for the failure of donor DBA CD8 T cells to mature into effector CTL in DBA→F1 mice, we examined donor and host populations at several early time points. To preclude the possibility that differences in B6 vs. DBA T cells reflect differences in host alloantigen recognition, we replaced B6 donors with B10.D2 donors, a strain in which the DBA/2 derived H-2 complex was introgressed onto the B57BL/10Sn background. The C57BL/10 strain has a background highly similar to C57BL/6 mice. Importantly, H-2d B10.D2 donors, like DBA donors, recognize F1 host H-2b. We have previously shown that acute GVHD in B10.D2 →BDF1 mice strongly resembles that of B6→F1 mice (20). Thus, the chronic GVHD phenotype in DBA→F1 is not a consequence of an H-2d donor recognizing a semi-allogeneic H-2b host. Importantly, the minor H-2 differences between C57BL/6 and C57BL/10 are not sufficient to cause a significant host vs. graft (HVG) response, a rejection of donor T cells or an alteration of acute GVHD phenotype (20).

F1 mice received unfractionated B10.D2 or DBA donor splenocytes adjusted to contain comparable numbers of CD4 T cells and comparable numbers of CD8 T cells. Significant differences between these two groups were seen at both day 5 and day 7 after transfer. Specifically, compared to DBA→F1 mice at either day 5 or day 7, donor CD4 and CD8 T cells from B10.D2 →F1 mice exhibit significantly greater numbers of total cells (Fig. 1A,1B), IFN-g expressing cells (Fig. 1C,1D) and KI-67 incorporating proliferating donor CD4 and CD8 T cells (data not shown). B10.D2→F1 mice also exhibit significantly greater numbers of activated donor CD4 and CD8 T cells i.e. CD44 upregulation or CD62L down regulation (data not shown), although the difference was not significant at day 5. Thus, compared to DBA→F1 mice, B10.D2 →F1 mice exhibit stronger donor T cell activation and a greater early Th1/CMI response similar to that reported for B6→F1 (22) whereas the early Th1 response in DBA→F1 mice is significantly impaired. The similarity between B10.D2→F1 and B6→F1 mice indicate that the defective Th1 response in DBA→F1 mice is not a consequence of H-2b host allorecognition by H-2d donor T cells.

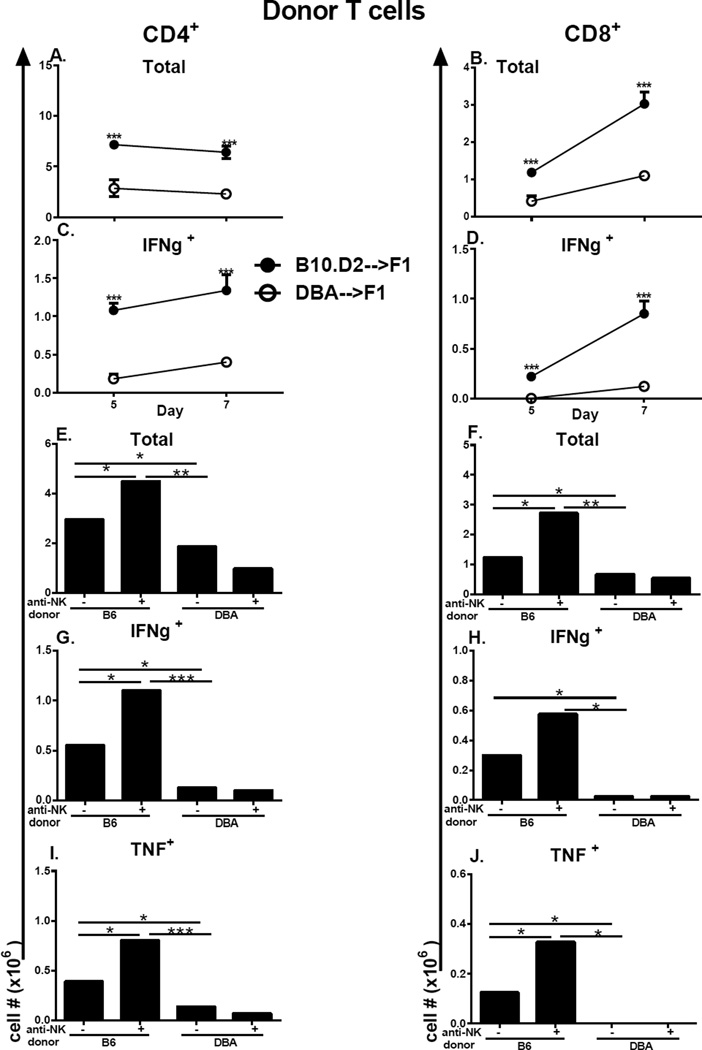

Figure 1. Defective in vivo Th1 cytokine expression by DBA T cells is not due to host NK function.

BDF1 mice received a single injection of unfractionated splenocytes from either B10.D2 or DBA donors. On day 5 and 7 after donor cell transfer, host spleens were evaluated by flow cytometry for donor T cell numbers of CD4 T cells (A, C) and CD8 T cells (B, D) to include total numbers (A, B) and intracellular IFN-g expression (C, D) as described in Methods. In panels (E–J), host F1 mice were either untreated or were depleted of NK cells prior to receiving unfractionated B6 or DBA splenocytes as described in Methods. Mice were assessed at day 7 by flow cytometry for total numbers of donor CD4 and CD8 T cells (E, F) and for intracellular expression of IFN-g (E–F) or TNF (G–H) in donor CD4 (E, G) and CD8 (F, H) T cells as described in Methods. Values represent group mean ± SE (n= 4–5/grp). Donor cells were examined by flow cytometry prior to transfer and the inocula adjusted so that each contained 5 × 106 CD8 T cells and 7.8–9.6 × 106 CD4 T cells. For all figures, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

It has been previously reported that host NK cells can alter lupus-like disease in DBA→F1 mice (29). To address whether the immune skewing of donor T cells seen in Figs. 1C–1D is a primary effect of donor T cells or a secondary consequence of differential host NK function, donor T cell skewing was assessed in B6→F1 and DBA→F1 mice depleted of host NK cells. NK depletion in B6→F1 mice enhanced total donor T cell engraftment and significantly boosted the numbers of donor CD4 and CD8 T cells expressing IFN-g and TNF (Figs. 1E–1J, columns 1 vs. 2,). NK depletion in DBA→F1 did not significantly alter donor T cell total numbers or numbers of IFN-g or TNF expressing donor T cells (Figs. 1E–1J, columns 3 vs. 4). Importantly, in NK-depleted groups, the disparity between for B6→F1 vs. DBA→F1 was even greater for total donor T cell engraftment and numbers of IFN-g and TNF expressing donor CD4 and CD8 T cells. Thus, host NK depletion does not reverse donor T cell immune skewing but instead exacerbates this effect supporting the conclusion that the early immune skewing of donor T cells is due to intrinsic differences in donor T cells rather than secondary to host NK cells. Moreover, these results are consistent with previously work, indicating that NK cells contribute to the counter regulatory host-vs. graft (HVG) response that impairs the donor T cell (particularly CD8) mediated GVH (22, 30). Because the donor CD8 GVH response is stronger in B6→F1 vs. DBA→F1 mice (22, 30), the boosting of donor T cell engraftment is significantly greater in the absence of host NK cells.

This differential Th1/CMI response in GVHD mice was not confined to donor T cells but also included host non-T cell populations as well. We examined a broad range of host non-T cell/APC populations (CD11c+ or CD11b+). No significant differences were seen at day 5 however by day 7 B10.D2 →F1 mice exhibit significantly greater numbers of: a) total CD11c+ or CD11b+ APC (Figs. 2A,B); b) IFN-g expressing APC (Figs. 2C, 2D); and c) TNF expressing APC (Figs. 2E, 2F) vs. DBA→F1 mice. Taken together with Fig. 1, these data confirm that B10.D2→F1 and B6→F1 exhibit a strong donor and host Th1/CMI response vs. DBA→F1 mice (22). Significant donor T cell differences are seen by day 5 whereas significant host differences are not seen until day 7 supporting the idea that host immune skewing is secondary to a primary intrinsic difference in donor T cells. Representative flow cytometry tracings from day 7 are shown in Supplemental Fig. 1.

Figure 2. Greater production IFN-g and TNF expression by host APC in B10.D2→F1 mice.

The cohort described in Fig.1A–1D was also analyzed for host DC subsets by flow cytometry. Gating strategy is as described in Methods. Shown are: CD11c+ cells (A, C, E) or CD11b+ cells (B, D, F) to include: total numbers (A, B); IFN-g expressing (C, D); TNF expressing (E, F). Values represent group mean ±SE.

Defective initial proliferation of DBA donor T cells

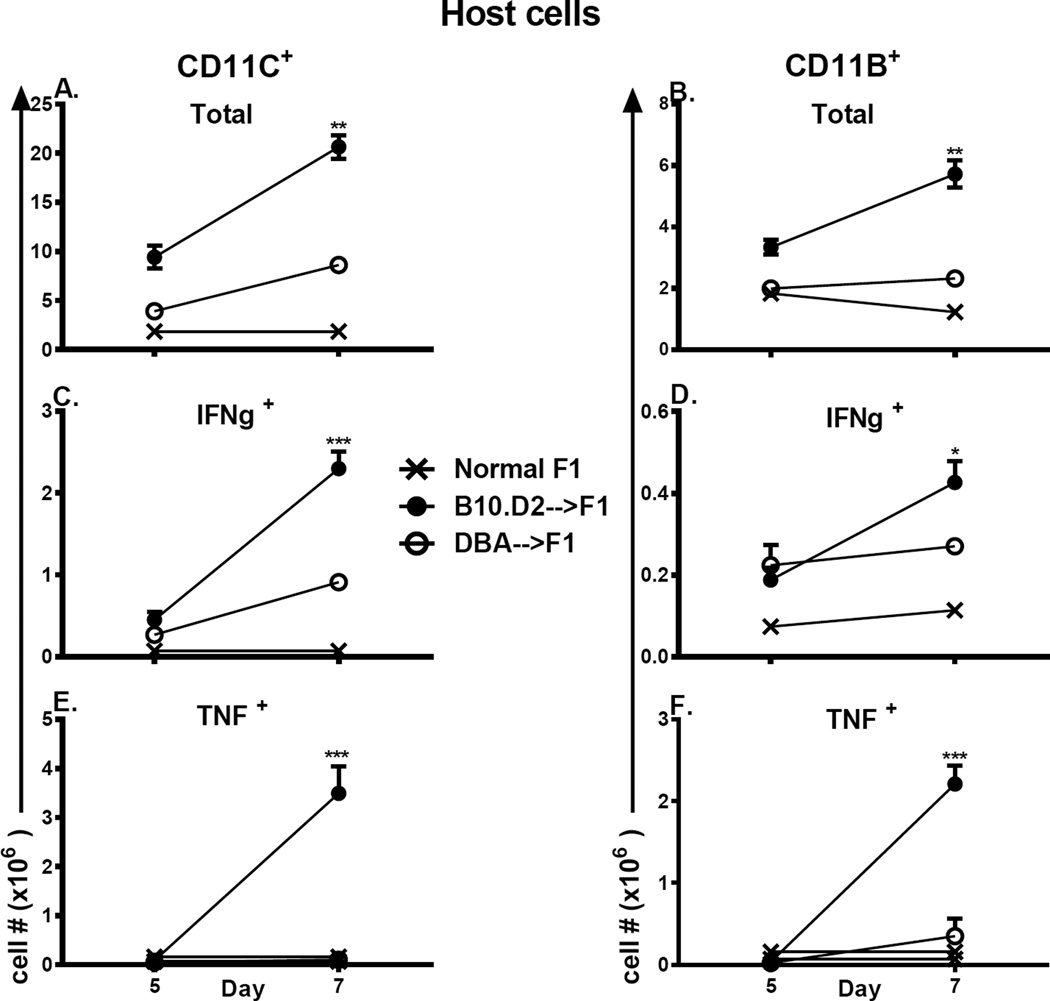

To determine whether the defects in DBA T cell expansion and maturation at days 5 −7 (Fig. 1) are preceded by even earlier defects, we examined initial donor T cell proliferation at days 3 and 4. Following transfer of CFSE-loaded, unfractionated donor splenocytes, we identified proliferating donor T cells by flow cytometry as Ki-67+,CFSE dull (at least one division). By day 3 after transfer, B10.D2 CD4 T cells exhibit a significantly greater percentage of dividing CD4 and CD8 T cells vs. DBA donors (Figs. 3A, 3B). By day 4, the percentage of dividing DBA T cells has increased for both CD4 and CD8 T cells but CD4 values are still significantly reduced for DBA vs. B10.D2 donors. A reciprocal analysis of undivided cells (Ki-67neg, CFSE bright) confirms these results and demonstrates that DBA→F1 have a significantly greater percentage of undivided CD4 (Fig. 3C) and CD8 T cells (Fig. 3D) at day 3. These differences persist at day 4 for CD4 T cells but narrow for CD8 T cells. These results support a defect in the initial activation kinetics of both DBA CD4 and DBA CD8 T cells vs. B10.D2 mice. Lastly, a kinetic analysis of splenic cytokine gene expression from the combined cohorts in Figs. 1–3 demonstrates a significant burst of IFN-g at day 7 for B10.D2→F1 mice that is not seen in DBA→F1 mice (Fig. 3E) replicating results comparing B6→F1 vs. DBA→F1 mice (20, 22). Thus, DBA→F1 mice exhibit impaired initial expansion of both DBA CD4 and CD8 T cells followed by impaired Th1 cytokine expression at days 5–7. The DBA CD8 expansion defect could be secondary to impaired DBA CD4 help as suggested by the defective day 3 DBA CD4 proliferation (Fig. 3A) however an intrinsic DBA CD8 defect cannot be excluded by these data.

Fig. 3. Initial DBA donor T cell proliferation is defective vs. B10.D2 T cells.

BDF1 mice received CFSE labeled DBA or B10.D2 (unfractionated) donor splenocytes and were assessed at day 3 and day 4 in separate experiments by flow cytometry expression of KI-67 and CFSE (see Methods). Proliferating donor CD4 (A) and CD8 (B) T cells are shown as the percent of KI-67 positive, CFSE-dull cells. Non proliferating CD4 (C) and CD8 (D) cells are shown as per cent of KI-67 negative, CFSE-bright cells. Donor cells were examined by flow cytometry prior to transfer and the inocula adjusted so that each contained 5 × 106 CD8 T cells and 7.8–9.6 × 106 CD4 T cells. Spleens from the cohorts in Figs. 1A–D and Fig. 3 were also examined by RT-PCR for IFN-g expression as a function of time after donor cell injection (E). Values represent group mean ±SE. n= 5 mice/group.

II. Results following transfer of purified donor CD4 and CD8 T cells

DBA CD4 T cell help for CD8 CTL is defective

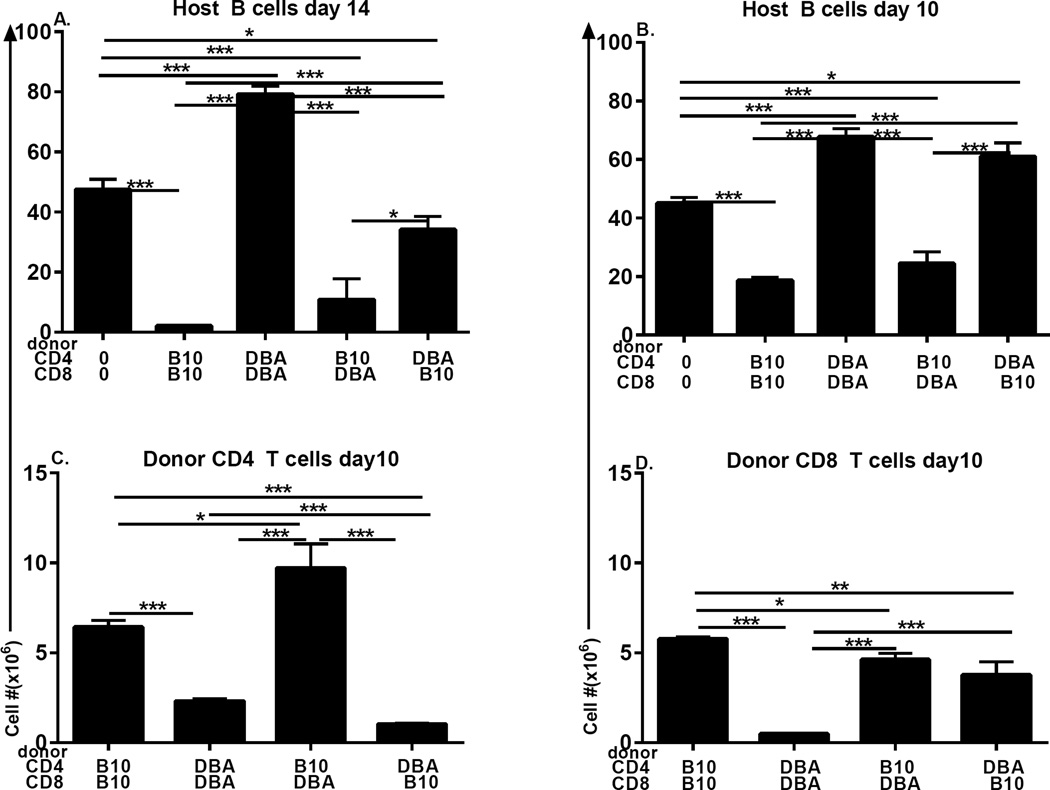

CD4 T cell help is critical for the maturation of naïve CD8 T cells into effector and memory CTL (31). The mechanism by which CD8 CTL maturation is defective in DBA→F1 mice (22) involves at least an intrinsic defect in DBA CD8 T cells (32), however the impaired proliferation of DBA CD4 T cells in Fig. 3 raises the possibility that a secondary defect in DBA CD4 T cell help for DBA CD8 CTL maturation may also be present. To address the individual roles of CD4 and CD8 T cells in generating in vivo CD8 effector CTL function, CD4 and CD8 T cells from B10.D2 and DBA donors were purified by negative isolation then re-paired in a mixed or matched manner prior to transfer into BDF1 hosts. To better detect a CD4 helper defect for CD8 CTL, donor inocula were equalized to contain an off-plateau dose of donor T cells at the lower limit of acute GVHD induction (7 × 106 CD4 and 4 × 106 CD8 T cells), as previously demonstrated (33, 34). Elimination of host B cells at days 10–14 has been shown to be a sensitive indicator of in vivo donor CTL killing in this model (22). Comparing day 14 host B cell numbers, control matched B10.D2 CD4 + B10.D2 CD8 (matched B10.D2→F1) donor cells induce significant and profound host B cell elimination compared to uninjected F1 mice (Fig. 4A, columns 1 & 2 from the left) typical of an acute GVHD cytotoxic phenotype and indicative of a strong B10.D2 CD8 CTL response (35). In contrast, matched DBA CD4 and DBA CD8 donor T cells (matched DBA→F1) induce significant host B cell expansion typical of the expected day 14 stimulatory chronic GVHD (Fig. 4A, columns 1 & 3 respectively) consistent with a failure of DBA CD8 CTL maturation. These positive controls for acute and chronic GVHD phenotype demonstrate that: a) purification and recombination of CD4 and CD8 T cell subsets does not alter the expected two week phenotypes observed in unfractionated donor splenocyte transfer experiments (35), and b) T cells are necessary and sufficient for GVHD induction.

Fig. 4. Defective DBA CD8 CTL reflects both an intrinsic CD8 defect and an extrinsic CD4 helper defect.

CD4 and CD8 T cells were each purified by negative isolation from DBA and B10.D2 spleens as described in Methods. BDF1 mice received either no donor cells or 7 × 106 CD4 T cells and 4 × 106 CD8 T cells from donor strains as designated on the x-axis. F1 mice were assessed by flow cytometry for (A) host B cells at day 14; (B) host B cells at day 10; and engraftment of donor CD4 (C) and CD8 (D) T cells at day 10. Values represent group mean ±SE. n= 3– 5 mice/group.

Mixing of donor T cell subsets further demonstrates the strain specific contribution for each subset. Strain differences in the strength of CD4 T cell help are seen by keeping the CD8 T cell strain constant and varying the source of CD4 T cells. For B10.D2 CD8 T cells, significant and profound killing of host B cells (vs. control F1) is seen when paired with B10.D2 CD4 T cells (Fig. 4A, columns 1 & 2) however killing is significantly reduced when paired with DBA CD4 T cells (Fig. 4A, column 5 vs. 2), indicative of a severe defect in DBA CD4 T cell help. Conversely, DBA CD8 T cell killing of B cells is profoundly impaired (vs. control F1) when paired with DBA CD4 T cells, but is significantly boosted by pairing with B10.D2 CD4 T cells (Fig. 4A, columns 1, 3 & 4) to levels comparable to matched B10.D2→F1 (Fig. 4A, column 2). Thus, regardless of the strain of CD8 T cell, CD4 T cell help is significantly reduced for DBA vs. B10.D2.

Conversely, an intrinsic CD8 T cell defect can be assessed by keeping the strain of CD4 T cell help constant and varying the strain of CD8 T cells. Using this approach, B10.D2 CD4 T cells promote profound and statistically comparable (p=n.s.) CD8 CTL elimination of host B cells (vs. control F1) regardless of the strain donor CD8 T cell pairing of (Fig. 4A, columns 1, 2 & 4). A different effect is seen with DBA CD4 T cells. The impaired host B cell killing observed when DBA CD4 T cells are paired with DBA CD8 T cells is significantly boosted (but not normalized) by pairing of DBA CD4 T cells with B10.D2 CD8 T cells (Fig. 4A, columns 1, 3 & 5). The difference in killing (i.e. B cell elimination) seen for mixed DBA CD4 + B10.D2 CD8 →F1 vs. matched DBA →F1 (Fig. 4A, columns 5 vs. 3) reflects an intrinsic DBA CD8 T cell defect that can also be significantly corrected with fully functional B10.D2 CD4 help (Fig. 4A, column 4) but is more pronounced when CD4 help is impaired.

Using this same approach of mixing or matching donor T cell subsets, a similar effect is seen at day 10 prior to maximal B cell elimination seen on day 14 (Fig. 4B). Keeping constant the strain of CD8 T cells, B10.D2 CD8 T cells induce significant host B cell killing when paired with B10.D2 CD4 T cells (Fig. 4B, columns 1 & 2) however, pairing with DBA CD4 T cells significantly abrogates B cell elimination to levels comparable to uninjected control F1 mice (Fig. 4B, columns 1, 2 and 5). Similarly, DBA CD8 T cells paired with B10.D2 CD4 T cells induce significant host B cell killing compared to uninjected F1 (Fig. 4B, columns 4 vs. 1) that is comparable to matched B10.D2→F1 mice (Fig. 4B, column 2 vs. 4, p=n.s.). This strong DBA CD8 T cell killing is completely abrogated when paired with DBA CD4 T cells (Fig. 4B, columns 3 vs. 4) confirming the CD4 helper defect demonstrated in Fig. 4A. Conversely, comparisons keeping constant the strain of CD4 T cells demonstrate that B10.D2 CD4 T cells induce efficient B cell killing whether paired with B10.D2 CD8 T cells or DBA CD8 T cells (Fig. 4B, columns 1, 2 and 4), whereas DBA CD4 T cells induce a statistically similar failure of CD8 CTL killing of B cells whether paired with DBA CD8 T cells or B10.D2 CD8 T cells (Fig. 4B, columns1, 3 and 5) indicative of a significant DBA CD4 T cell helper defect. The intrinsic DBA CD8 defect at day 14 (Fig. 4A, columns 3, 5) is not detectable at day 10 (Fig. 4B).

Thus, using host B cell elimination as a marker of in vivo donor CTL activity, at both days 10 and 14, DBA CD4 T cell help for normal B10.D2 CD8 T cells is defective, relative to the helper function of B10.D2 CD4 T cells. By contrast, defective DBA CD8 CTL function seen when paired with DBA CD4 T cells is significantly corrected and nearly normalized by pairing with B10.D2 CD4 T cells. A milder intrinsic DBA CD8 defect is seen only at day 14 and can be significantly boosted by B10.D2 CD4 T cell help. Moreover, at both day 10 and 14, mixed B10.D2 CD4 + DBA CD8 →F1 exhibit B cell killing comparable to control matched B10.D2→F1 (Figs. 4A and 4B, columns 2 & 4) and significantly greater than mixed DBA CD4 + B10.D2 CD8→F1 (Figs. 4A and 4B, column 5), indicating that B10.D2 CD4 T cell help compensates for an intrinsic DBA CD8 defect. Importantly, DBA CD4 T cell help cannot induce optimal CD8 CTL function in normal B10.D2 CD8 T cells (Figs 4A, 4B columns 2 vs. 5). Together, these results strongly support a model in which defective DBA CTL generation is the result of a profound defect in DBA CD4 T cell help in combination with a milder intrinsic DBA CD8 T cell defect.

CD4 T cell help for CD8 engraftment and maturation is defective in DBA mice

In the p→F1 model of acute GVHD, donor CD8 T cell engraftment peaks at ~day 10 and then undergoes homeostatic contraction (22). To further clarify the respective roles of DBA CD4 and CD8 T cells in defective CTL effector function, we examined peak (day 10) donor CD4 and CD8 engraftment in the cohort shown in Fig. 4B using mixed or matched donor T cell subsets. Despite injecting equal numbers of purified donor CD4 T cells, B10.D2 donors exhibited significantly greater CD4 engraftment than DBA donors regardless of their CD8 T cell pairing. Specifically, B10.D2 CD4 engraftment (Fig. 4C, columns 1 & 3) is significantly greater than DBA CD4 engraftment (Fig. 4C, columns 2 or 4), consistent with their greater B10.D2 CD4 proliferation and expansion shown in Figs. 1–3.

Regarding CD8 T cell engraftment (Fig. 4D), control matched B10.D2 →F1 mice exhibit the expected strong engraftment of CD8 T cells whereas control matched DBA →F1 mice exhibit the expected significantly impaired CD8 engraftment (Fig. 4D, columns 1 vs. 2) consistent with previous work (22). For experimental mixed groups, the defective DBA CD8 engraftment seen when DBA CD8 are paired with DBA CD4 T cells (Fig. 4D, column 2) is significantly boosted by pairing with B10.D2 CD4 T cells (Fig. 4D, column 3) consistent with defective DBA CD4 help. However, the level remains slightly but significantly less than that of matched control B10.D2 →F1 (Fig. 4D, column 1) consistent with an intrinsic DBA CD8 defect. Similarly, the robust B10.D2 CD8 engraftment seen when paired with B10.D2 CD4 T cells (Fig. 4D, column 1) is significantly reduced, but not abrogated, when B10.D2 CD8 T cells are paired with DBA CD4 T cells (Fig. 4D, column 4), consistent with a DBA CD4 helper defect. Importantly, B10.D2 CD8 engraftment in DBA CD4 + B10.D2 CD8→F1 mice (Fig. 4D, column 4) is significantly greater than that of DBA CD8 engraftment in matched control DBA→F1 mice (Fig. 4D, column 2) indicative of an intrinsic DBA CD8 T cell defect since both groups have the same source of CD4 T cell help.

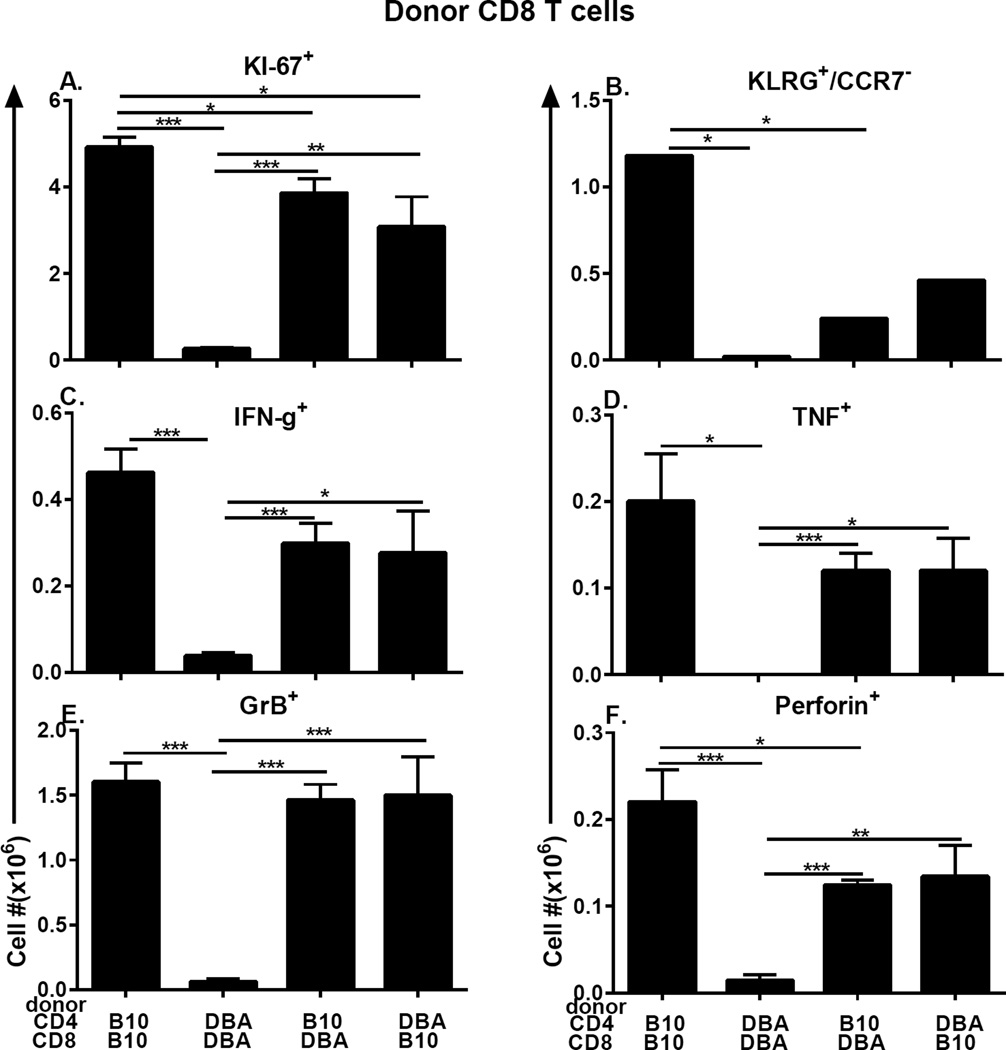

Engrafted donor CD8 T cells were further examined for markers of effector maturation and activation to include Ki-67, short lived effector cells (KLRG-1+, CCR7-), and intracellular IFN-g, TNF, pfp and GrB. Representative flow cytometry tracings are shown in Supplemental Fig. 2. All markers are readily detectable in matched B10.D2→F1 acute GVHD controls and are profoundly defective in matched DBA→F1 chronic GVHD controls as expected (Fig. 5, columns 1 & 2 for all panels). Experimental groups (Fig. 5, columns 3 & 4, all panels) receiving mixed donor strain T cells were largely intermediate between the two controls.

Fig. 5. Intracellular markers of CD8 CTL effector maturation are defective in DBA CD8 T cells due to an intrinsic defect and extrinsic DBA CD4 helper defect.

The cohort shown in Fig. 4B–4D was also examined by flow cytometry at day 10 for donor CD8 T cell: (A) KI-67+ proliferating cells; (B) SLEC (KLRG-1pos, CCR7neg) cells; and intracellular expression of (C) IFN-g, (D) TNF, (E) GrB, (F) perforin. Values represent group mean ±SE. n= 5 mice/group.

Comparisons keeping constant the CD8 T cell strain and varying the CD4 T cell strain demonstrate that for B10.D2 CD8 T cells, all markers are expressed at strong levels when paired with B10.D2 CD4 T cells (Fig. 5, all panels, column 1) however pairing with DBA CD4 T cells (Fig. 5, all panels, column 4) diminishes B10.D2 CD8 expression of all markers except GrB but reaches significance only for Ki-67. Similarly DBA CD8 T cells paired with DBA CD4 T cells exhibit profoundly impaired expression of all markers compared to matched B10.D2→F1 controls (Fig. 5, all panels, columns 1 vs. 2) however pairing DBA CD8 with B10.D2 CD4 improves (but does not normalize) the DBA CD8 defect (Fig. 5 all panels columns 2 vs. 3) for all markers and reaches significance for all but KLRG-1+ SLEC demonstrating that the intrinsic defect in DBA CD8 T cells can be significantly improved when defective DBA CD4 T cell help is replaced by functionally normal B10.D2 CD4 T cells.

Comparisons keeping constant the CD4 T cell strain and varying the CD8 T cell strain demonstrate that B10.D2 CD4 T cells induce strong expression of all markers in B10.D2 CD8 T cells (Fig. 5, all panels, column 1). However, pairing of B10.D2 CD4 T cells with DBA CD8 T cells (Fig. 5, all panels, column 3) yields intermediate to normal levels of analyzed markers, consistent with a DBA CD8 intrinsic defect. DBA CD4 T cells induce poor expression of all markers in DBA CD8 T cells (Fig. 5, all panels, column 2) but pairing with B10.D2 CD8 T cells (Fig. 5 all panels, column 4) results in significantly greater expression of all markers except KLRG-1+ SLEC, further supporting the conclusion that there is an intrinsic defect in DBA CD8 T cells.

Taken together, the results of Figs. 4 and 5 support the conclusion that DBA CD4 T cells are defective helpers for CD8 CTL maturation because: 1) defective DBA CD8 day 10 expansion/effector maturation and day 10–14 killing can be significantly corrected by B10.D2 CD4 T cell help; and 2) DBA CD4 T cells are unable to induce normal day 10 CTL parameters when paired with B10.D2 CD8 T cells. Conversely, evidence of an intrinsic DBA CD8 defect is seen by the failure of B10.D2 CD4 T cells to fully normalize DBA CD8 engraftment and effector marker expression.

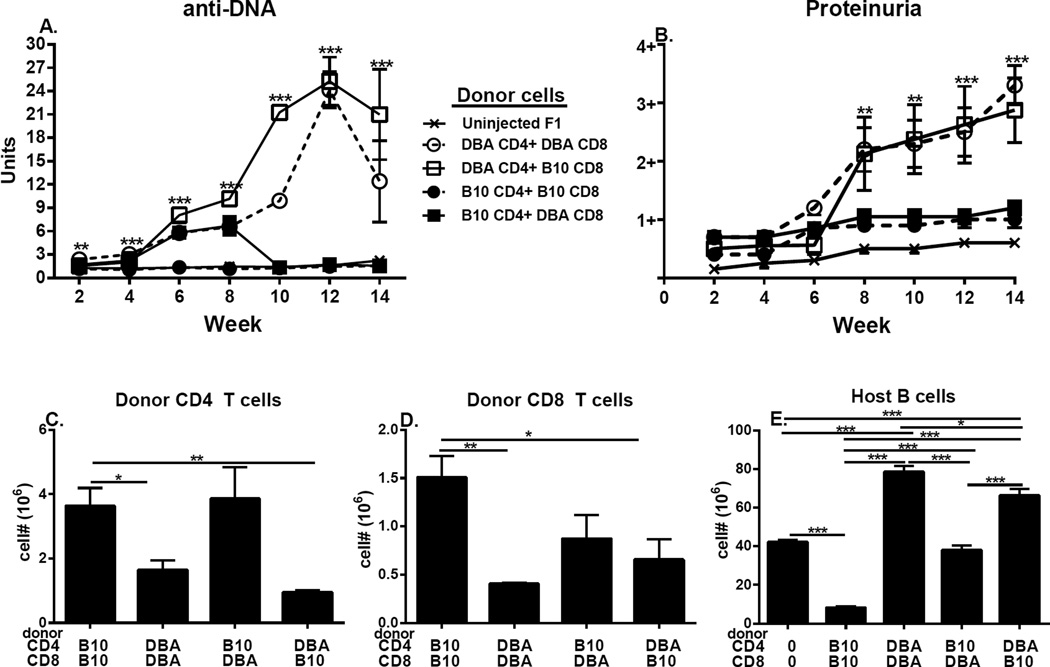

Long term effects: DBA CD4 T cells induce greater lupus-like renal disease regardless of CD8 T cell strain pairing

Using the same experimental protocol of mixing and matching donor T cell subsets described for Figs. 4 & 5, p→F1 mice were observed long term (14 weeks) for evidence of T cell driven-B cell hyperactivity as shown by serum anti-DNA Ab (Fig. 6A) and lupus-like renal disease as shown by proteinuria (Fig. 6B). Control, matched DBA→F1 mice exhibited significant elevations over control uninjected mice for: 1) anti-DNA Ab levels beginning at week 2 and peaking at week 12 and 2) proteinuria progressing to 3+ (Figs. 6A & B, open circles, dotted line), indicative of severe lupus-like nephritis and mimicking the severe lupus nephritis reported following the transfer of unfractionated DBA donor splenocytes into BDF1 mice (12). These results confirm that: 1) only T cells are required for disease (i.e. no donor APC or non-T cells were injected); and 2) negative isolation of donor cells does not alter the expected phenotype long term. By contrast, no sustained significant elevations over uninjected control F1 mice are seen in either parameter for matched B10.D2→F1 mice (Fig. 6 A & B, closed circles, dotted line), consistent with previous reports of B6→F1 acute GVHD long term survivors (36). For mice receiving mixed donor T cell subsets, sustained significant elevations in serum anti-DNA and in proteinuria are seen only in F1 mice receiving DBA CD4 T cells paired with B10.D2 CD8 T cells (Fig. 6A & B, open squares, solid line). Values did not differ significantly from control matched DBA→F1 mice. Conversely, F1 mice receiving mixed B10.D2 CD4 + DBA CD8 T cells (Fig. 6A & B, closed squares, solid line) exhibited an early significant increase in anti-DNA ab but after 8 weeks values returned to control levels. This transient increase in anti-DNA ab levels was not accompanied by significantly elevated proteinuria. Renal histological analysis revealed lupus-like nephritis only in groups receiving DBA CD4 T cells (i.e. DBA CD4 + DBA CD8→F1 and DBA CD4+ B10.D2 CD8→F1; data not shown).

Fig. 6. DBA CD4 T cells are lupus prone regardless of the strain of paired CD8 T cells.

Experimental protocol is as described in Fig. 4. F1 mice were assessed serially for: (A) serum anti-DNA ab and (B) proteinuria. At 14 weeks, F1 spleens were assessed by flow cytometry for: (C) donor CD4 T cells, (D) donor CD8 T cells and (E) host B cells. Values represent group mean ±SE. n=3–5/group.

Long term donor T cell engraftment results (Fig. 6 C & D) mirror the day 10 engraftment trends (Fig. 4 C & D) with DBA CD4 T cell engraftment (regardless of CD8 pairing) being significantly lower than matched B10.D2 control CD4 T cells (Fig. 6C, columns 2 & 4 vs. 1). Similarly, CD8 engraftment is significantly less for DBA matched controls vs. B10.D2 matched controls (Fig. 6D, columns 1 & 2) and mixed groups exhibit impaired long term CD8 engraftment vs. matched B10.D2→F1 (Fig. 6D, columns 3 & 4 vs. 1). Despite the reduced DBA CD4 engraftment, host B cell expansion is significantly greater in F1 mice receiving DBA CD4 T cells vs. B10.D2 CD4 T cells, regardless of the CD8 T cell pairing (Fig. 6E, columns 3 & 5 vs. 2 & 4). Taken together, the data in Fig. 6 support the conclusion that DBA CD4 T cells exhibit greater lupus inducing potential than do B10.D2 CD4 T cells despite their reduced long term engraftment vs. B10.D2 CD4 T cells. Furthermore, the lupus promoting effect of DBA CD4 T cells is not mitigated by the presence of intrinsically normal B10.D2 CD8 T cells, likely as a result of poor CD4 help for B10.D2 CD8 CTL.

III. Results following transfer of purified CD4 donor T cells alone

Qualitative differences in donor CD4 activation: B10.D2 CD4 T cells promote CD8aDC and CMI whereas DBA CD4 T cells promote pDC expansion and severe lupus

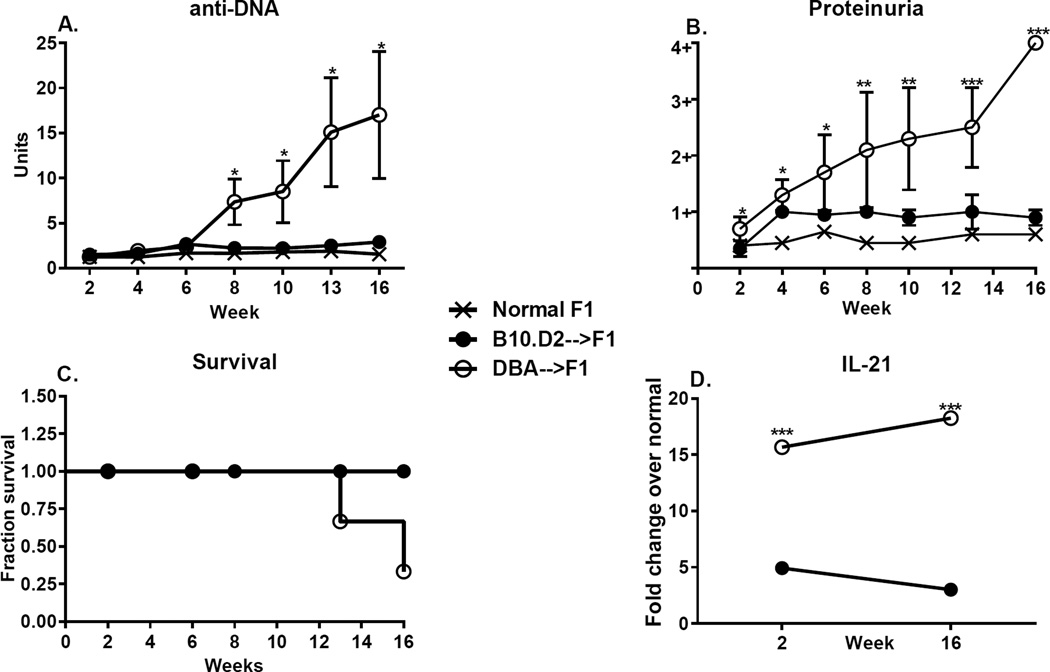

In the p→F1 model, transfer of parental CD4 T cells in the absence of CD8 T cells induces a lupus-like chronic GVHD however, the degree of resemblance to human lupus and severity of disease varies with the parent and F1 strain combinations used (14). Although host genetics have been shown to contribute to disease expression (11), the role of donor CD4 T cells in shaping disease outcome has not been fully addressed. The forgoing data strongly support the idea that DBA CD4 T cells exhibit qualitative differences in vivo compared to B10.D2 CD4 T cells and that these qualitative differences result in a differential lupus inducing proclivity. To address this possibility, we compared immunologic parameters in BDF1 mice at two weeks and twelve weeks after the transfer of purified DBA (DBA CD4→F1) or B10.D2 CD4 T cells (B10.D2 CD4→F1). In the absence of parental strain CD8 T cells, host splenocytes are not eliminated in either transfer at days 10–14 and mice develop a chronic GVHD phenotype both short and long term. (10, 33, 37)

Following transfer of equivalent numbers of donor CD4 T cells, DBA CD4→F1 mice exhibit significantly greater donor CD4 engraftment vs. B10.D2 CD4→F1 at both week 2 and week 16 (Fig. 7A). These results are in contrast to Figs. 3 & Fig. 6 where B10.D2 CD4 T cells are significantly greater than DBA CD4 T cells both short and long term, a difference that likely relates to the co-injection of donor CD8 T cells which have been reported to promote CD4 expansion (30). Greater DBA CD4 engraftment is associated with significantly greater DBA CD4 TfhCD4 cells both short and long term (Fig. 7B). Although these levels of CD4 Tfh cells are very low for DBA donors, they are nevertheless detectable, whereas values for B10.D2 donors are below the limits of detection. Regarding host CD4 T cells, DBA CD4→F1 mice also exhibit a significant increase over control F1 mice in the numbers of host total CD4 and Tfh CD4 cells both short and long term (Fig. 7C, 7D). No significant increase over control F1 for either of these host parameters is seen for B10.D2 CD4→F1 mice at either time. An increase in host CD4 T cell numbers is typical of chronic GVHD (12) and these results support the idea that chronic GVHD is severe in DBA CD4→F1 mice and mild in B10.D2 CD4→F1 mice.

Total host B cell numbers (Fig. 7E) and GC B cells (GL-7+)(Fig. 7F) were significantly elevated over control for both B10.D2 CD4→F1 and DBA CD4→F1 mice at 2 weeks. However, by 16 weeks, only DBA CD4→F1 continued to exhibit significant elevations over control in either parameter. These data support the conclusion that only DBA CD4→F1 mice exhibit sustained CD4 driven-B cell activation and auto Ab production. Lastly, striking differences in host APC subsets were observed. At 2 weeks, B10.D2 CD4→F1 mice exhibit a significant (~3.5 fold) increase in CD11c+, CD8a+ DC vs. DBACD4→F1 (Fig. 7G) whereas DBA CD4→F1 mice exhibited a significant (~2.5 fold) increase in pDC vs. B10.D2 CD4→F1 mice (Fig. 7H). Neither difference was maintained long term and DBA CD4→F1 mice had a slight but significant increase in CD11c CD8a+ DC vs. B10.D2→F1 at week 16. These results suggest that differential DC subpopulation expansion is an important early event in disease induction.

Taken together, the flow cytometry data in Fig. 7 indicate a more severe and sustained CD4 T cell driven, B cell activation DBA CD4→F1 mice than for B10.D2 CD4→F1. This conclusion is further supported by significantly greater serum anti-DNA Ab levels (Fig. 8A) and significantly greater proteinuria (Fig. 8B) in DBA CD4→F1 vs. B10.D2 CD4 → F1 mice. The greater renal disease was associated with earlier mortality in the DBA CD4 →F1 group (Fig. 8C) prompting termination of the experiment and assessment of the surviving mice. Lastly, splenic IL-21 gene expression was significantly greater for DBA CD4→F1 mice vs. B10CD4→F1 mice at both 2 and 16 weeks (Fig. 8D). Regarding gene expression of other cytokines, splenic IL-4 expression for DBA CD4→F1 was significantly elevated at two weeks vs. B10.D2 CD4→F1 but by 16 weeks, elevations were no longer significant (data not shown). Conversely, IFN-g levels were elevated at two weeks for B10.D2 CD4→F1 vs. DBA CD4→F1 but failed to reach statistical significance (data not shown). Expression of other splenic cytokines (IL-6, IL-10, Mx-1, OAS) were ≤3-fold increased vs. control F1 in both groups at both time points and were non-informative (data not shown).

Fig. 8. Purified DBA CD4 T cells induce greater lupus-like disease than do purified B10.D2 CD4 T cells.

The cohort described in Fig. 7 was serially evaluated for (A) serum anti-DNA ab, (B) proteinuria and (C) survival. Splenic IL-21 gene expression is shown in (D). Values represent group mean ±SE.

Two distinct gene expression signatures in DBA CD4→F1 vs. B10.D2 CD4→F1 mice

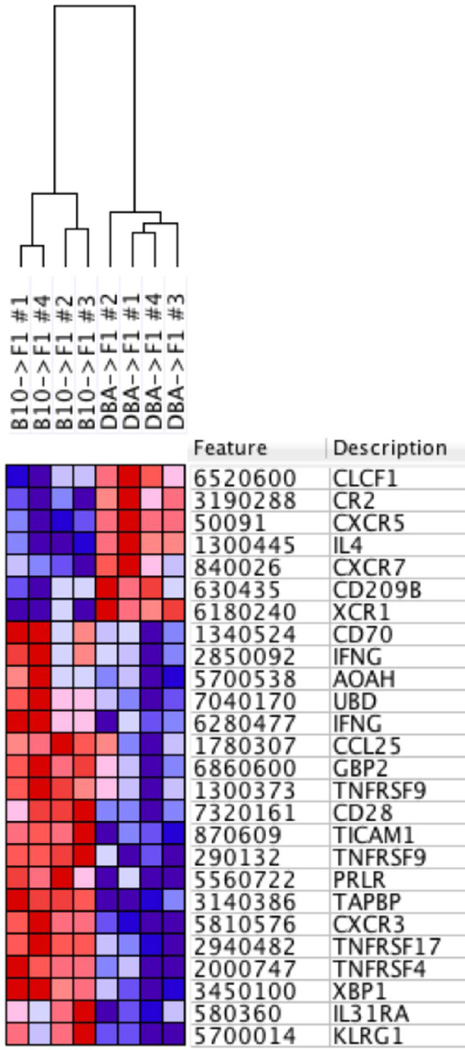

The foregoing results support the conclusion that DBA CD4 T cells exhibit an immune activation pathway in vivo that is significantly different from that of B10.D2 CD4 T cells, despite both p→F1 combinations exhibiting host B cell expansion and a chronic GVHD phenotype at two weeks. To determine whether these two pathways exhibit distinct gene expression signatures, spleens from B10.D2 CD4→F1, DBA CD4→F1, and uninjected control mice were profiled by genome-wide gene expression analysis at day 14, using Illumina BeadArray methodology (see Methods). The complete results are at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=sjkvggcovxsvvqx&acc=GSE71611; accession number: GSE71611. Differential expression analysis resulted in identification of more than 300 candidate genes with greater than 4-fold expression ratio and p-value < 0.05 between DBA CD4→F1 vs. B10.D2→F1 (Supplemental Fig. 3). Gene set enrichment analysis identified a significant subset of 24 high confidence immune response-associated candidate genes that completely stratifies the two conditions (Fig. 9). Previously reported elevations in IL-4 mRNA levels for DBA→F1 mice (20) and as also noted above for DBA CD4→F1 were confirmed in DBA CD4→F1 mice, whereas B10.D2→F1 mice exhibited an increase in IFN-g typical of acute GVHD (Fig. 9 rows 4, 9 & 12) (20). Moreover, CXCR5 (Fig. 9, row 3) was greater in DBA CD4→F1 consistent with greater CD4 Tfh activity and B cell help. An analysis of T cell activation and expansion related genes (Supplemental Fig. 4) indicated that B10.D2 CD4 T cells induce greater IL-31Ra, BCL2L11, CD28 and TNFRSF9 (4-1BB) whereas DBA CD4→F1 mice exhibit have greater BH3 Interacting Domain Death Agonist (BID), and protein kinase C alpha (PRKCA). Furthermore, control F1, DBA->F1 and B10.D2→F1 gene expression signatures are significantly stratified after unbiased hierarchical clustering (Figure 9). The three-fold increase in IL-21 mRNA for DBA CD4→F1 vs. B10.D2 CD4→V1 seen in Fig. 8D was not strong enough to be detected as significantly different by gene array. Because differences in IL-2 by protein or mRNA are best seen during days 1–3 (20, 38), we did not include IL-2 related genes in our analysis. Taken together, the disparate gene expression in these two p→F1 combinations further supports the conclusion that CD4 T cells from B6 and DBA mice induce two highly distinct lymphocyte activation pathways.

Fig. 9. DBA CD4→F1 vs. B10.D2→F1 exhibit two different pathways of immune gene activation.

Purified donor CD4 T cells were transferred into BDF1 mice as described for Figs. 7 & 8, and host spleens from B10.D2 CD4->F1 and DBA CD4->F1 mice (n=4/group) were profiled by whole-genome expression analysis at day 14 using Illumina BeadArray methodology (see Methods). Heat map of differentially expressed genes (red = higher, blue = lower expression) was generated by data output from GenomeStudio and analysis using GenePattern and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis.

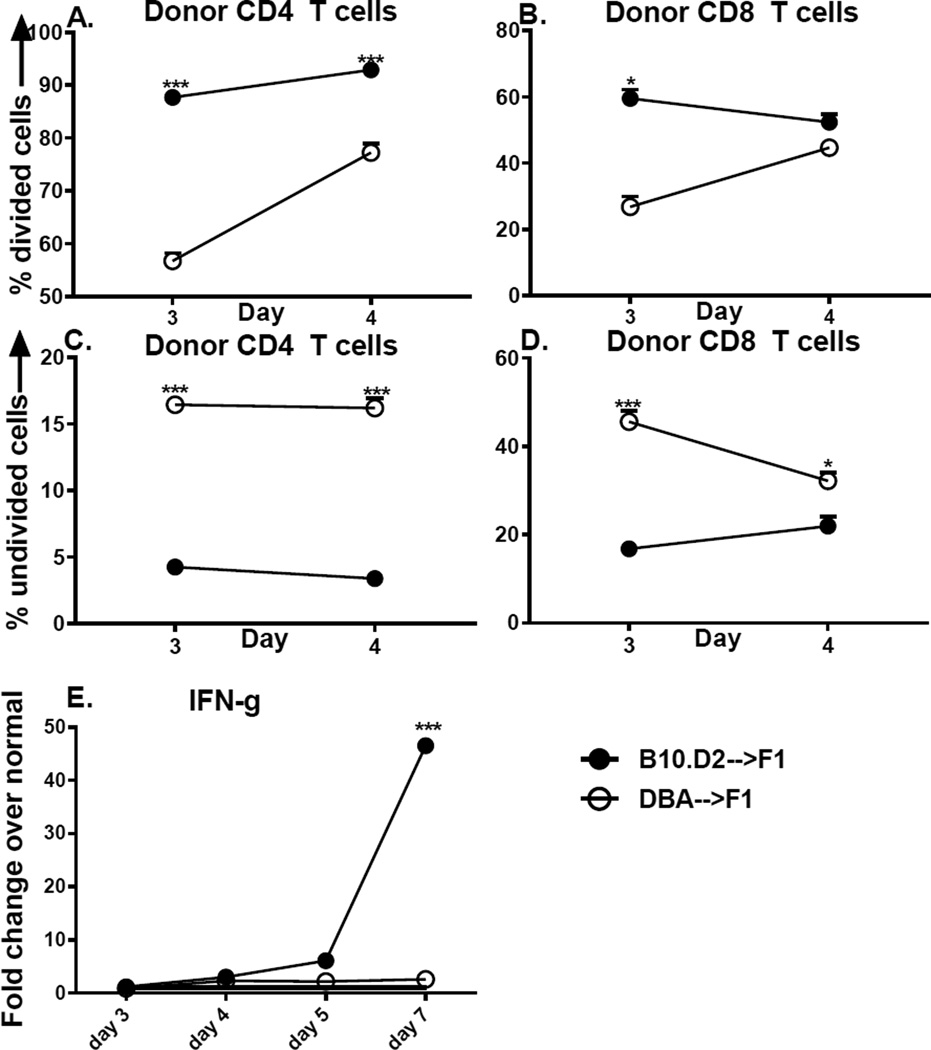

DBA CD4 T cells exhibit defective in vitro IL-2 production and intracellular signaling

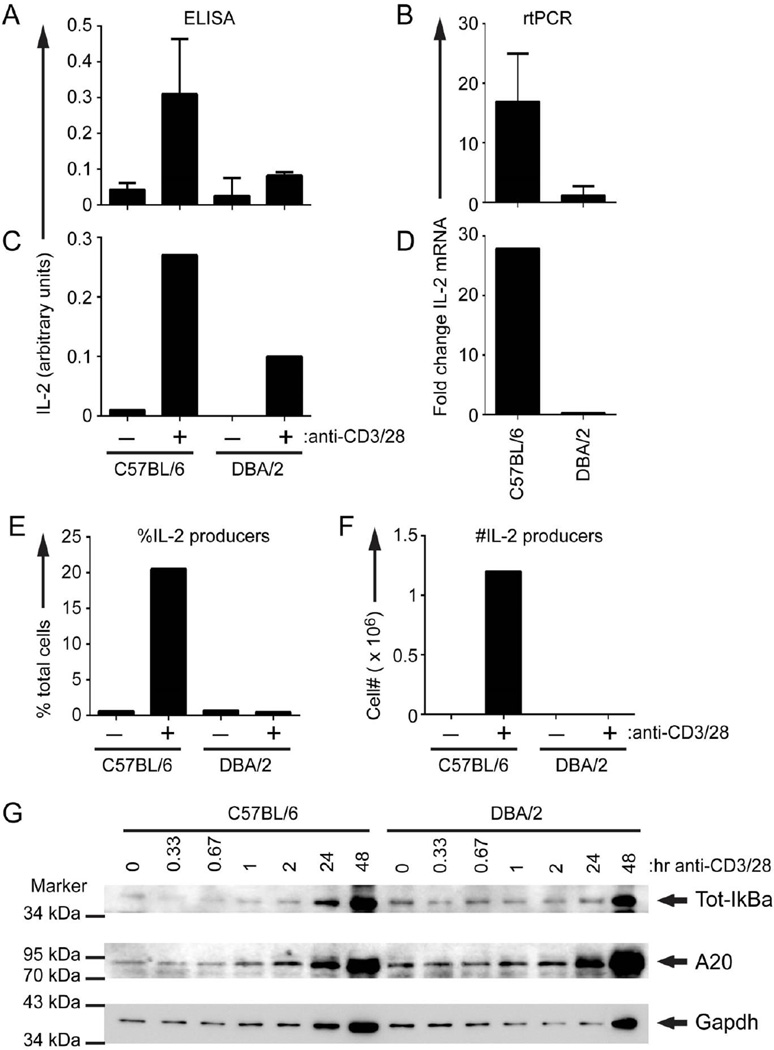

The foregoing results demonstrate two distinct lymphocyte activation pathways in B10.D2 CD4→F1 vs. DBA CD4→F1 mice. These observations suggest the existence of pre-existing intrinsic differences in the default activation pathways used by B10.D2 or DBA CD4 T cells, possibly due to intrinsic differences in TCR-stimulated IL-2 production. IL-2 has critical roles in naïve CD4 T cell proliferation, in CD4 help for CD8 CTL and in IFN-g expression (31, 39–41), all of which are defective in DBA CD4 T cells (Figs. 1, 3, 4 & 5). These results are consistent with previous work demonstrating a relative defect for in vivo and ex vivo IL-2 production in DBA →F1 vs. B6→F1 mice (20, 38). To address whether the in vivo functional defects in IL-2 reflect a pre-existing intrinsic defect in DBA T cells, we examined in vitro IL-2 parameters following maximal TCR stimulation. Because host alloantigen recognition is not a concern and B6 and B10.D2 behave similarly (i.e. strong Th1/CMI response), we compared anti-CD3/anti-CD28 stimulated DBA and B6 splenocytes and observed significantly impaired IL-2 protein and mRNA expression by DBA splenocytes (Figs. 10A, 10B).

Figure 10. Defective IL-2 production and intracellular IL-2 signaling in DBA CD4 T cells.

B6 or DBA mice were tested for maximal IL-2 production using unfractionated splenocytes (A, B) or purified CD4 T cells (C–F) as described in Methods. At 48 hours supernatants were harvested and tested for IL-2 content by ELISA (A, C) and cells were harvested for IL-2 mRNA expression by PCR shown as fold increase over unstimulated (B, D) or intracellular IL-2 expression by flow cytometry as shown by per cent positive (E) or total number of cells (F). For all wells, the number of plated DBA CD4 T cells and B10.D2 CD4 T cells was equal. In preliminary studies, we were unable to detect IL-2 by ELISA before 48 hours. For (A, B), values represent group means ± SE, n=4 mice/group. For (C – E), spleens were pooled from 12 mice/group. (G) The same population of purified CD4 T cells used in (C–F) was stimulated for the indicated times with plate-bound anti-CD3 (145-2C11, 100 µg/mL) and anti-CD28 (37.51, 10 µg/mL). Whole cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-IκBα (Cell Signaling Technology, 9246), anti-A20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-166692), and anti-GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-32233).

To confirm the CD4 specificity of the IL-2 defect, purified CD4 T cells pooled from age and sex matched donors were tested in parallel for in vitro IL-2 parameters and intracellular signaling. Defective in vitro IL-2 production and mRNA expression was seen for DBA vs. B6 pooled CD4 T cells (Figs. 10C, 10D). Intracellular IL-2 expression was also impaired in DBA CD4 T cells (Fig.10E, 10F) but was not associated with greater numbers or percentage of Foxp3+ CD4 T cells (data not shown). Thus, DBA CD4 T cells have a defect in IL-2 production at the level of transcription of the IL-2 gene.

The pooled CD4 T cells from B6 or DBA mice shown in Figs. 10C–10F were also examined for TCR-dependent activation of NF-kB, a key regulator of IL-2 transcription. To assess the kinetics of TCR-dependent NF-κB activation, we monitored degradation of IκBα. Prior to TCR stimulation, NF-κB is sequestered in an inactive state in the cytoplasm by IκBα. TCR activation triggers the proteasomal degradation of IκBα, leading to nuclear translocation of NF-κB. Thus, IκBα degradation is a measure of NF-κB activation. Stimulation of purified B6 CD4 T cells with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 caused degradation of IκBα at 20 and 40 min post-stimulation. CD4 DBA T cells had higher basal levels of IκBα and showed a more transient degradation of IκBα that was only apparent at 20 min post-TCR stimulation (Fig 10G). Additionally, we examined the glycolytic gene, GAPDH, which is induced by the autocrine action of IL-2 (42). By 24 hr post-stimulation, B6 CD4 T cells exhibited increased levels of IκBα and GAPDH protein (Fig. 10G), indicative of NF-κB-dependent IL-2 production (IκBα is resynthesized in an NF-κB-dependent manner). By contrast, these changes in protein expression in DBA CD4 T cells were delayed until 48 hr post-stimulation, consistent with the observed defect in IL-2 production by DBA T cells. Finally, western blotting showed that CD4 DBA T cells have higher basal levels of A20, a negative regulator of NF-κB activation (43, 44) linked to SLE (45), (Fig. 10G). Also, TCR induction of A20 was more robust in DBA T cells, particularly by 48 hr post-stimulation. It should be noted that these studies were performed on purified donor strain CD4 T cells at up to 48 hours of in vitro stimulation whereas the gene array studies in Fig. 9 were performed on F1 mice 14 days after donor cell transfer. Because of these differences, NF-κB related genes were not included in the gene array studies. Together, these data demonstrate that DBA CD4 T cells have a pre-existing defect in TCR activation of NF-κB, which likely contributes to the observed impairment of IL-2 transcription. Increased basal and TCR-induced production of A20 may contribute to the poor NF-κB response of DBA CD4 T cells.

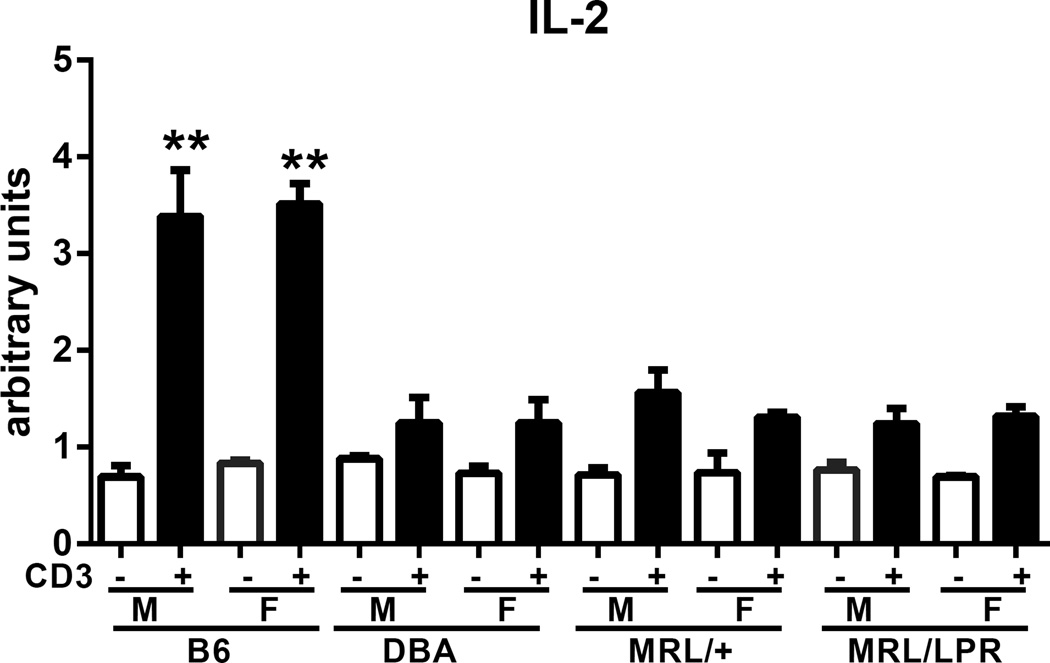

Defective in vitro IL-2 production by DBA T cells is comparable to that of lupus-prone MRL mice

Defective in vitro IL-2 production is a well reported in both human and murine lupus (46). To determine the relative severity of the DBA IL-2 defect, we compared in vitro IL-2 production from young (10 weeks) DBA splenocytes to that of young age matched lupus-prone MRL/+ and MRL/lpr splenocytes. Both sexes were tested and normal B6 splenocytes were the positive control. Confirming our results in Fig. 10A, DBA IL-2 production was significantly reduced compared to that of B6 mice but was not significantly different from MRL/lpr or MRL/+ mice (Fig.11). Within a given strain, there were no significant sex differences in IL-2 production. These results indicate that the severity of the DBA IL-2 defect is comparable to that of young autoimmune prone MRL mice.

Fig. 11. Defective in vitro DBA IL-2 production is comparable to that of MRL spontaneous lupus mice.

Splenocytes from 10-week-old male and female B6, DBA, MRL/+ and MRL/lpr were tested in vitro for anti-CD3 IL-2 production as described in Methods. Values represent the mean ± SE of 3 mice/group. Open bars are unstimulated and solid bars are stimulated.

Discussion

CD4 T cells play an essential role in lupus pathogenesis by providing help to autoreactive B cells that in turn produce the pathogenic autoantibodies mediating tissue injury (29, 47). This study advances our understanding of the critical role of CD4 T cells by demonstrating that pre-existing differences in the inherent strength of CD4 T cell help for B cells can shape the severity of lupus expression. Using MHC identical but background gene disparate strains, we observed that following an experimentally induced loss of tolerance, CD4 T cells from H-2d mice of the C57 black background induced transient autoantibodies without major lupus renal disease whereas equivalent numbers of CD4 T cells from H-2d DBA mice induced prolonged autoantibody elevations and severe lupus nephritis. These striking differences in the CD4 lupus-inducing potential were associated with two contrasting patterns of in vivo CD4 T cell activation. Naïve B10.D2 CD4 T cells induced a strong Th1/CMI response characterized by robust initial T cell proliferation, IL-2 and IFN-g expression, CD4 help for CD8 CTL effector maturation with skewing towards CTL-promoting CD8a+ DC expansion and away from pDC expansion. This pattern was seen in association with reduced CD4 Tfh cells, transient autoantibody production and mild lupus nephritis. By contrast, CD4 T cells from H-2d DBA mice exhibited weak initial proliferation, reduced IL-2 and IFN-g expression, poor help for CD8 CTL with skewing away from CD8a+ DC expansion and towards pDC expansion. This pattern was associated with greater CD4 Tfh cell numbers, sustained autoantibody production and severe lupus nephritis. These results are consistent with reports that Tfh cells are increased in lupus (48) and that strong T cell stimulation is needed for Th1 differentiation but is not needed for Tfh cell differentiation (49). Differential immune skewing of donor T cells was not secondary to host NK cell function.

An analysis of activated genes from whole spleens confirmed two different gene activation pathways are induced. Three hundred genes exhibited significant differences between the two p→F1 groups and 24 high confidence immune response gene differences were identified. B10.D2 CD4→F1 mice exhibited gene expression changes typical of acute GVHD in B6→F1 or B10.D2→F1; i.e. elevated IFN-g, KLRG-1 and TNFR related genes with reduced IL-4. The reverse was seen in DBA CD4→F1 mice. The full implications of these differentially expressed genes requires further study. However these results support our conclusion that CD4 T cells exhibit strain based differences in their default helper response as a consequence of differential initial IL-2 production. The mechanism by which a defect in CD4 T cell IL-2 production skews towards excessive help for B cells and the potential role of Tregs is currently under study.

These results also demonstrate that following an experimental loss of tolerance, the inherent lupus-inducing proclivity of CD4 T cells is a reciprocal relationship between the ability to provide help for B cells vs. the ability to provide help for CD8 CTL. Specifically, the striking lupus proclivity of DBA CD4 T cells relates to strong and sustained B cell help coupled with impaired help for CD8 CTL whereas the weak lupus proclivity of C57/black background B10.D2 CD4 T cells relates to strong help for CD8 CTL coupled with reduced help for B cells, an effect that is seen even in the absence of donor CD8 T cells. The pattern of strong Th1/CMI and weak B cell help by B10.D2 CD4 T cells is also seen in B6 CD4 T cells supporting a role for non-MHC genes (37). Because lupus related autoantibodies are produced by host (F1) B cells, our results demonstrate that autoreactive B cells are normally present and quiescent in non-lupus prone BDF1 mice however, these B cells can be readily induced to secrete pathogenic autoantibodies following a loss of CD4 T cell tolerance depending on the strength of CD4 T cell help for B cells.

Although an intrinsic CD8 defect in DBA CTL maturation has been demonstrated (20, 32), its effect on CTL maturation appears to be modest compared to the more extensive extrinsic defect in DBA CD4 T cell help. The intrinsic DBA CD8 defect could be largely, but not entirely, corrected by normal B10.D2 CD4 T cell help whereas the DBA CD4 helper defect strongly compromised the maturation of normal B10.D2 CD8 T cells. Importantly, pairing of DBA CD4 T cells with normal B10.D2 CD8 T cells did not mitigate the strong lupus inducing proclivity of DBA CD4 T cells indicating that despite the important role played by CD8 T cells in down regulating lupus both in the p→F1 model and other murine models (see below), the lupus down regulatory activity of CD8 T cells is critically dependent on CD4 T cell function.

The mechanisms by which CD4 T cells help CD8 T cells mature into effector CTL have been recently delineated (reviewed in (31, 39, 50–52). Briefly, following TcR engagement and CD28 mediated costimulation, CD8 T cells expand and express effector markers GrzB, pfp, IFN-g and TNF. CD4 T cells help CTL maturation by: 1) licensing CD11c+, CD8a DC through CD40:CD40 ligand interactions, and 2) providing IL-2 which drives both effector and memory CD8 development. Stimulation of CD8 T cells by licensed DC in the absence of IL-2 induces effector CTL but poor memory CD8 function. IL-2 signaling through the high-affinity IL-2R directly induces T-bet expression, STAT-1 signaling, grzB/pfp upregulation and effector expansion. These effects are directly proportional to the strength of the IL-2 signaling. Inflammatory cytokines IL-12 and IFN-a, termed signal 3, also promote effector and memory CTL in part by enhancing the sensitivity of CD8 T cells to IL-2 signaling. Thus, CD4 help for CD8 CTL includes both IL-2 production and licensing of CD11c+DC and possibly other, as yet undefined factors.

Our results demonstrating defective DBA CD4 T cell help for CTL raised the possibility that DBA CD4 T cells have a pre-existing defect in IL-2 production. Previous work in the p→F1 model using BDF1 mice as hosts has been consistent with defective IL-2 production in DBA vs. B6 donors. DBA→F1 mice have been reported to exhibit defective initial IL-2 dependent donor T cell proliferation, ex vivo IL-2 production and IL-2 gene expression compared to B6→F1 mice (20, 38). Because IFN-g production is largely IL-2 dependent (41), defective IFN-g expression in DBA T cells is likely a consequence of impaired initial IL-2 production. In those studies however, a direct comparison of IL-2 production by equal numbers of purified donor CD4 T cells was not performed. In the present study, equal numbers of donor CD4 T cells tested in vivo or in vitro revealed a striking defect in IL-2 production in DBA vs. B10.D2 CD4 T cells.

Follow up in vitro experiments were performed to show that DBA CD4 T cells have an intrinsic defect in TCR activation of NF-κB, which may underlie the observed defect in IL-2 transcription. Mechanistically, the impaired activation of IL-2 in DBA CD4 T cells may be due to high basal and TCR-induced levels of A20, an ubiquitin editing enzyme which negatively modulates cytoplasmic signaling to NF-kB (43, 44). Importantly, polymorphisms in the human A20 gene region are associated with lupus (45). Our data therefore suggest a possible mechanism connecting dysregulated expression of A20 in CD4 T cells with lupus. Thus, defective DBA CD4 help for CD8 CTL maturation is likely a combination of defective IL-2 production and defective licensing of CD8a+DC as demonstrated in Figs. 7 & 10 and previously (22). Conversely, pDC have been linked to lupus activity (53) and the excessive pDC activation seen in DBA→F1 mice (Fig. 7) may also inhibit CTL responses as excessive pDC activation has been reported to inhibit anti-viral CTL responses (54).

The reduced CD8 CTL function seen in DBA→F1 lupus mice is a common feature in human and murine lupus. In general, CD8 T cells are critical in limiting tolerance breaks in normal mice and they fail in lupus prone mice (55). Defects in CD8 mediated lupus down regulation have been reported in NZB/W (56–58), MRL/lpr (59, 60) and BxSB lupus mice (61, 62). Also, Qa-1 restricted CD8 T cells have been reported to down regulate Qa-1 expressing Tfh cells and prevent lupus (63). In p→F1 mice, donor CD8 CTL can prevent donor CD4-driven lupus (10, 64) and lupus develops when donor CD8 CTL fail to mature (10). However as our results demonstrate, the severity of the ensuing lupus in the absence of CD8 CTL relates to the intrinsic lupus-inducing proclivity of the CD4 T cell.

In human lupus, CD8 CTL function is reported as defective both in vitro and in vivo (reviewed in (46). CD8 CTL are absolutely required for control of EBV infection (65) and lupus patients exhibit impaired EBV CD8 CTL responses (66) and higher viral loads (67). As described above, IL-2 is important in CTL maturation and defective IL-2 production is a longstanding and robust finding in both human and murine lupus (46, 68). Although APC defects contribute, lupus T cells exhibit an intrinsic defect in IL-2 production due to an imbalance in the CREM/CREB ratio in the IL-2 promoter region (69). Despite the robustness of defective IL-2 in lupus, its meaning remains incompletely understood. Specifically, does defective IL-2 production represent a primary, pre-existing defect central to lupus pathogenesis or is it a secondary defect that is just one of many examples of the disordered immunoregulation characteristic of lupus? The two possibilities are not mutually exclusive and a secondary defect is well documented. In human lupus, defective in vitro IL-2 production varies with disease severity (70, 71). In spontaneous lupus mice, defective in vitro IL-2 production increases with age and disease severity (reviewed in (46, 68). In DBA->F1 mice, defective IL-2 production by normal BDF1 host splenocytes is observed as early as two weeks after donor transfer supporting the idea that defective IL-2 production can be induced and is an early marker of lupus activity (32). Lastly, imbalances in the CREM/CREB ratio in the IL-2 promoter region can be induced by lupus serum (69).

A primary, pre-existing defect in lupus T cell IL-2 production has been difficult to assess. The exact time of disease onset is unknown in spontaneous lupus mice and prospective identification of human lupus patients pre-disease is problematic. Additionally, the presence of a secondary IL-2 defect complicates detection of a primary defect. Nevertheless, supportive evidence is provided by Stohl et. al. (72–74) who, using a re-directed lysis assay and PBL from monozygotic twins discordant for SLE, demonstrated defective killing by both the affected twin and the unaffected twin. These results are consistent with a primary lupus cytolytic defect that is possibly IL-2 dependent. A primary pre-existing defect T cell in IL-2 is further supported by our data demonstrating that DBA CD4 T cells exhibit defective in vitro and in vivo IL-2 production that, following an experimental loss of tolerance results in immune skewing away from help for down regulatory CD8 CTL and towards excessive help for B cells and sustained lupus.

It is important to note that DBA mice do not develop lupus spontaneously despite exhibiting an IL-2 defect comparable to that of lupus prone MRL mice. Thus, the primary IL-2 defect in DBA CD4 T cells by itself is not sufficient for lupus expression however following and experimental loss of tolerance i.e. the transfer of DBA CD4 T cells into non-lupus prone BDF1 hosts, florid lupus ensues in F1 mice. By contrast, lupus seen following the transfer of high IL-2 producing donor CD4 T cells (B10.D2 CD4→F1 or B6 CD4→F1) is milder and tolerance is eventually restored. These strain dependent differences in CD4 activation pathways demonstrate that the same initiating Ag (allogeneic host MHC II, I-Ab) can induce either a CMI/CTL response or a lupus response depending on the pre-existing intrinsic response pattern of the responding donor CD4 T cell. Taken together, these results advance a novel paradigm in lupus pathogenesis. Currently, lupus is thought to result when a genetically predisposed individual encounters an environmental lupus trigger. Our results provide a mechanism by which environmental stimuli could induce lupus in a select group of individuals whose CD4 T cells exhibit a pre-existing DBA-like skewing towards prolonged help for B cells and away from IL-2 and help for CD8 CTL. Should such lupus prone individuals encounter a trigger requiring a strong CD8 CTL response for protective immunity (e.g., EBV), they will exhibit skewing towards a non protective Ab response resulting in persistence of antigen and immune stimulation rather than a protective CTL response with Ag clearance. Moreover, EBV is able to infect B cells in a non Ag-specific manner through its binding to CD21, thereby rendering potentially all B cells, regardless of their Ag specificity, as “foreign” and potential targets for help by an oligoclonal population of Ag-specific CD4 T cells. This situation is analogous to DBA→F1 mice where an oligoclonal population of donor CD4 T cells provides help to all host MHC II-disparate B cells resulting in lupus-specific Ab as previously described (10, 64). The link between EBV and human lupus is controversial and we are not proposing it is a causative trigger, but rather that it exemplifies the qualities a lupus trigger would require to induce disease in individuals with DBA like CD4 T cell skewing, i.e. the ability to render potentially all B cells as foreign. Regardless of EBV’s etiologic role in lupus, impaired CD8 CTL control of EBV in lupus patients discussed above is indicative not necessarily of EBV’s etiologic role but rather it is a manifestation of a lupus related IL-2 mediated CTL defect, most likely secondary to disease but in some instances possibly due to primary DBA-like CD4 T immune skewing with impaired IL-2 production.

Clearly, lupus expression is a final common pathway of a number of immune defects. Because DBA→F1 mice strongly mimic the human lupus subset of renal disease, lupus specific autoantibodies, reduced IL-2 and defective CD8 CTL, the immune skewing shown by DBA CD4 T cells likely illustrates an important mechanism applicable to at least a subset of human lupus. Specifically, humans may exhibit genetically predetermined DBA-like CD4 T cell skewing, which may itself be multifactorial to include individuals with a reduced intrinsic CD4 T cell IL-2 capacity. Such pre-existing, genetically determined non–adaptive immunologic skewing has been documented in murine Leishmania major infection where B6 mice make a protective CMI response and BALB/c make a non-protective Ab response (75, 76). Moreover, experimental CMI promotion with rIL-12 in BALB/c mice was curative, whereas Ab promotion in B6 mice exacerbated disease (77). Similarly, immunomodulation in DBA→F1 mice has also been effective with agents that either enhance CTL formation or inhibit their down regulation prevent lupus short term (22, 34, 78). These results raise the possibility of a novel therapeutic approach in humans. At present, standard lupus therapy is associated with global immunosuppression. A variety of immune molecules are being targeted for blockade, however, these will likely be accompanied by some level of immunodeficiency because targeted molecules are important in normal immune function. Our results support a new approach aimed at skewing CD4 T cells away from B cell help and towards help for CD8 CTL, i.e. promoting CMI at the expense of Ab responses. Such an approach could not only be beneficial but would also avoid the problems inherent in long-term immunosuppression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health AI047466 and R56 AI047466 (CSV) and GM109887 (BCS).

We thank Cara Olsen, Ph.D., Preventive Medicine and Biometrics, USUHS, for helpful discussions and advice regarding statistical approaches.

Abbreviations used

- BDF1

B6D2F1

- B6

C57Bl/6

- B10.D2

B10.D2-Hc0 H2d H2-T18c/oSnJ

- DBA

DBA/2J

- EBV

Epstein-Barr virus

- GC

germinal center

- GrB

granzyme B

- HVG

host-vs.-graft

- KO

knock out

- p→F1

parent-into-F1

- pfp

perforin

- Tfh

T follicular helper

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors, and are not necessarily representative of those of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), the Department of Defense (DOD); or, the United States Army, Navy, or Air Force.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mohan C, Adams S, Stanik V, Datta SK. Nucleosome: a major immunogen for pathogenic autoantibody-inducing T cells of lupus. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1367–1381. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linterman MA, Rigby RJ, Wong RK, Yu D, Brink R, Cannons JL, Schwartzberg PL, Cook MC, Walters GD, Vinuesa CG. Follicular helper T cells are required for systemic autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2009;206:561–576. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bubier JA, Sproule TJ, Foreman O, Spolski R, Shaffer DJ, Morse HC, 3rd, Leonard WJ, Roopenian DC. A critical role for IL-21 receptor signaling in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus in BXSB-Yaa mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1518–1523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807309106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shlomchik MJ, Aucoin AH, Pisetsky DS, Weigert MG. Structure and function of anti-DNA autoantibodies derived from a single autoimmune mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:9150–9154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shlomchik MJ, Marshak-Rothstein A, Wolfowicz CB, Rothstein TL, Weigert MG. The role of clonal selection and somatic mutation in autoimmunity. Nature. 1987;328:805–811. doi: 10.1038/328805a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burlingame RW, Rubin RL, Balderas RS, Theofilopoulos AN. Genesis and evolution of antichromatin autoantibodies in murine lupus implicates T-dependent immunization with self antigen. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:1687–1696. doi: 10.1172/JCI116378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shlomchik M, Mascelli M, Shan H, Radic MZ, Pisetsky D, Marshak-Rothstein A, Weigert M. Anti-DNA antibodies from autoimmune mice arise by clonal expansion and somatic mutation. J Exp Med. 1990;171:265–292. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radic MZ, Weigert M. Genetic and structural evidence for antigen selection of anti-DNA antibodies. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:487–520. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsokos GC. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2110–2121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1100359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Via CS. Advances in lupus stemming from the parent-into-F1 model. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:236–245. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Portanova JP, Ebling FM, Hammond WS, Hahn BH, Kotzin BL. Allogeneic MHC antigen requirements for lupus-like autoantibody production and nephritis in murine graft-vs-host disease. J Immunol. 1988;141:3370–3376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster AD, Haas M, Puliaeva I, Soloviova K, Puliaev R, Via CS. Donor CD8 T cell activation is critical for greater renal disease severity in female chronic graft-vs.-host mice and is associated with increased splenic ICOS(hi) host CD4 T cells and IL-21 expression. Clin Immunol. 2010;136:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grader-Beck T, Casciola-Rosen L, Lang TJ, Puliaev R, Rosen A, Via CS. Apoptotic splenocytes drive the autoimmune response to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 in a murine model of lupus. J Immunol. 2007;178:95–102. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gleichmann E, Gleichmann H. Pathogenesis of graft-versus-host reactions (GVHR) and GVH-like diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1985;85:115s–120s. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12275619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gleichmann E, Van Elven EH, Van der Veen JP. A systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)-like disease in mice induced by abnormal T-B cell cooperation. Preferential formation of autoantibodies characteristic of SLE. Eur J Immunol. 1982;12:152–159. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830120210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenberg RA, Via CS. T cells, murine chronic graft-versus-host disease and autoimmunity. Journal of autoimmunity. 2012;39:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris SC, Cohen PL, Eisenberg RA. Experimental induction of systemic lupus erythematosus by recognition of foreign Ia. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;57:263–273. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(90)90040-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puliaiev M, Puliaev R, Puliaeva I, Soloviova K, Via C. Both perforin (pfp) and Fas ligand (FasL) contribute to control of autoreactive B cells and retard lupus like disease in parent-into-F1 mice. The Journal of Immunology. 2010;184:143–145. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puliaev R, Nguyen P, Finkelman FD, Via CS. Differential requirement for IFN-gamma in CTL maturation in acute murine graft-versus-host disease. J Immunol. 2004;173:910–919. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rus V, Svetic A, Nguyen P, Gause WC, Via CS. Kinetics of Th1 and Th2 cytokine production during the early course of acute and chronic murine graft-versus-host disease. Regulatory role of donor CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 1995;155:2396–2406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soloviova K, Puliaiev M, Foster A, Via CS. The parent-into-F1 murine model in the study of lupus-like autoimmunity and CD8 cytotoxic T lymphocyte function. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;900:253–270. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-720-4_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puliaev R, Puliaeva I, Welniak LA, Ryan AE, Haas M, Murphy WJ, Via CS. CTL-promoting effects of CD40 stimulation outweigh B cell-stimulatory effects resulting in B cell elimination and disease improvement in a murine model of lupus. J Immunol. 2008;181:47–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]