Abstract

Both protein kinase B (Akt) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) are down-stream components of the insulin/insulin like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) signaling pathway. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is known to sensitize cells to insulin/IGF-1 signaling. The objective of this study was to assess the activity of AMPK and its role in the observed down-regulation of insulin/IGF-1 signaling in cotyledonary (COT) arteries supplying the placental component of the ewe placentome. Nonpregnant ewes were randomly assigned to a control (C, 100% of NRC recommendations) or obesogenic (OB, 150% of NRC) diet from 60 days before conception until necropsy on day 75 of gestation (n = 5/group) or until lambing (n = 5/group). At necropsy on day 75 of gestation, the smallest terminal arteries that entered the COT tissues (0.5–1.0 mm in diameter) were collected for analyses. Fetal weights were ~20% greater (P < 0.05) on OB than C ewes, but birth weights of lambs were similar across dietary groups. Fetal plasma concentrations of glucose, insulin and IGF-1 were higher (P < 0.05) in the blood of fetuses from OB than C ewes. Total AMPK and phosphorylated AMPK at Thr 172 (the active form) were reduced (P < 0.05) by 19.7 ± 8.4% and 25.9 ± 7.7%, respectively in the COT arterial tissues of OB ewes. Total acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), a down-stream target of AMPK, and its phosphorylated form were also reduced (P< 0.05) by 32.9 ± 9.2% and 45.4 ± 14.6%, respectively. The phosphorylation of IRS-1 at Ser 789, a site phosphorylated by AMPK, was 24.5 ± 9.0% lower (P< 0.05) in COT arteries of OB than C ewes. No alteration in total insulin receptor, total IGF-1 receptor or their phosphorylated forms was observed, down-stream insulin signaling was down-regulated in COT arteries of OB ewes, which may have resulted in the observed decrease in COT vascular development in OB ewes.

Keywords: Maternal obesity, Placentome, Vascularity, Insulin, Sheep, IGF-1

1. Introduction

In the sheep, there are 70-120 individual units of fetal:maternal exchange called placentomes [1]. Each placentome is composed of placental (cotyledonary; COT) and uterine (caruncular, CAR) components. Cotyledons are tufts of vascularized chorionic villi which develop adjacent to crypts on the CAR, which form button like protrusions on the uterine luminal surface. The COT and CAR then interdigitate to form the placentomal units [1]. Previously, we reported that COT vascularity increased in response to early gestational maternal under-nutrition in the cow and ewe [2,3], which would increase the ability of the fetus to acquire optimal delivery of maternal nutrients and oxygen [4]. We further demonstrated that the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK/ERK1/2) pathway and the phosphoinositide-3 kinase/protein kinase B (PIP3K/Akt) pathway were up-regulated in COT arteries under maternal nutrient restriction, in association with increased placentomal vascularity [2,3]. Adequate placental vascularity is essential for the extraction of maternal nutrients to maintain optimal growth and development of the rapidly growing fetus. Insulin/IGF-1 signaling exerts its biological effects mainly through activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway [5-10]. The binding of insulin to its receptor leads to phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), a key mediator of insulin signaling [6,7,11]. Phosphorylated IRS-1 recruits and activates PI3K/Akt signaling, which further activates mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling [12]. In addition, phosphorylation of IRS-1 also leads to the activation of MAPK [13,14]. Therefore, it is quite possible that insulin/IGF-1 signaling is involved in the overall regulation of PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK1/2 signaling in response to nutrient availability. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) has a central role in the control of energy metabolism, which sensitizes insulin signaling through phosphorylation of IRS-1 at Ser 789 [15]. Thus, AMPK may mediate the insulin/IGF-1 signaling in sheep placenta due to nutrient mediated changes in vascularity.

To date, the effects of maternal over-nutrition and obesity on modulating the insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway and placental vascular development have not been determined. The objective of the current study is to assess the temporal association between insulin/IGF-1 signaling, AMPK, and changes in placentomal vascularity occurring in response to maternal over-nutrition and obesity in the ewe.

2. Research design and methods

2.1. Care and use of animals

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Wyoming Animal Care and Use Committee. From 60 days before conception to day 75 of gestation (necropsy group) or lambing (lambing group), multiparous Rambouillet × Columbia ewes were placed in individual pens and fed either a highly palatable diet at 100% (control, C) of National Research Council (NRC) recommendations or 150% (obesogenic, OB) of NRC recommendations on a metabolic BW basis (BW0.75). Ewes were weighed at weekly intervals so that individual diets could be adjusted for changes in body weight, as previously described [16]. On day 45 of gestation, the number of fetuses carried by each ewe was determined by ultrasonography (Ausonics Microimager 1000 sector scanning instrument; Ausonics Pty Ltd, Sydney, Australia). Ten C ewes and 10 OB ewes carrying twin fetuses were utilized in this study. Though there was no difference in fetal weight and length between sexes, the sex of fetuses was balanced across dietary groups.

Maternal and fetal blood samples and fetal tissues were obtained at necropsy from C (n = 5) and OB (n = 5) ewes at 75 days of gestation. The remaining five pregnant ewes in each of the C and OB dietary groups were continued on their respective diets until term and were allowed to lamb unassisted. Birth weights and gestation lengths were then recorded. Immediately before necropsy on day 75, each ewe was weighed, and a sample of blood was collected via jugular venipuncture into a chilled nonheparinized vacutainer tube (no additives, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and serum frozen at −80 °C until assayed for insulin and IGF-I. A separate chilled tube (heparin plus sodium fluoride; 2.5 mg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was collected, and plasma frozen at −80 °C until assayed for glucose. Ewes were then sedated with Ketamine (22.2 mg/kg body wt, i.v.) and maintained under isoflurane inhalation general anesthesia (2.5%). Following midventral laparotomy, the gravid uterus was located and the umbilical cord supplying blood to each fetus was located. Umbilical venous blood was collected from each fetus via venipuncture and serum and plasma were collected and stored as described for maternal blood. Ewes and fetuses were euthanized by exsanguination while still under general anesthesia and the gravid uterus and fetuses quickly removed and placed on ice.

2.2. Tissue collection

Immediately after collection, each gravid uterine horn was opened from base to tip. For each conceptus, the smallest terminal arteries that entered the COT tissues (0.5-1.0 mm in diameter) were immediately collected from five similar size type A placentomes within 10 cm of the umbilical attachment and frozen in liquid nitrogen for later protein extraction and western blotting. Two additional type A placentomes of similar size and location were then dissected free of surrounding tissue and weighed and utilized for vascular area density analysis as described below. All remaining placentomes were then dissected from each gravid uterine horn and counted, then manually separated into their COT and CAR components and each component weighed. All placentomes present in the uteri of both C and OB ewes were found to be type A using the criteria described previously [17]. The fetus was then weighed, eviscerated, then weighed again.

2.3. Vascular area density measurement

COT arteriolar vascular density was determined by procedures previously published from our laboratory [18]. As described above, two placentomes were dissected from the surrounding tissue and weighed. A cross section of each placentome containing CAR and COT tissue was placed in a tissue cassette (Tissue Tek, Miles Labs, Elkhart, IN) and fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in a phosphate buffer (0.12 M; pH 7.4) and paraffin embedded. Twelve 5-μm sections evenly spaced over a 450-μm area of each placentome were evaluated for resistance arteriolar vascular area density (i.e., COT blood vessel area/COT area) via image analysis (Optimus Image Analysis Software, Bothell, WA) as previously described (see Vonnahme et al. [18] for tissue depiction and details). Briefly, maternal and fetal blood vessels were counted and traced within four fields for each of the twelve 5-μm section at points where the caruncular and adjacent cotyledonary tissue of the placentome could both be visualized. The blood vessel area per unit tissue area (i.e., cotyledonary blood vessel area/cotyledonary area) was calculated.

2.4. Antibodies

Antibodies against AMPK (Cat # 2532), phospho-AMPK at Thr 172 (Cat # 2535), ACC (Cat # 3662), phospho-ACC at Ser 79 (Cat # 3661), IRS-1 (Cat # 2382), phospho-IRS-1 at Ser 789 (Cat # 2389), Akt (Cat # 9272), phospho-Akt at Ser 473(Cat # 9271), mTOR (Cat # 2972), phospho-mTOR at Ser 2448 (Cat # 2971), ERK (extracellular regulated kinase)1/2 (Cat # 9102), phosphorylated ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204, Cat # 9101), insulin receptor beta (Cat # 3025), IGF-1 receptor (Cat # 3027) and phosphor-IGF-I receptor (Tyr1131)/insulin receptor (Tyr1146) (Cat # 3021) were purchased from cell signaling (Danvers, MA). Anti-β-actin (Cat # A1978) antibody was purchased from Sigma (Saint Louis, Missouri).

2.5. Immunoblot analysis

Cotyledonary arteries were pooled by gravid uterine horn for each ewe, and were powdered in liquid nitrogen, then 0.1 g powdered artery was homogenized in a polytron homogenizer (7-mm diam. generator) with 5 vol of ice-cold lysis buffer [20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 2% SDS, 1% NP-40, 100 mM NaF, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO)]. The homogenates were sonicated and clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Cat # 500-0116, Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd). The resulting supernatant was mixed with the same volume of 2× standard SDS sample loading buffer and heated at 95 °C for 5 min. Then, 30 μg protein extractions were separated by 5–15% SDS-PAGE gradient gels, using a Mini-Protean III™ Gel electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd). Following electrophoresis, the resolved proteins on the gel were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (0.45 μm pore size) (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd) using a Bio-Rad mini-transblot electrophoretic transfer cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd). Following transfer, membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk powder in TBST (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6,150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20) for 2 h. Blocked membranes were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibodies (1 to 1000 dilution in TBST with 5% BSA). At the end of the primary antibody incubation, the membranes were washed with TBST three times, for 15 min each. After that, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. After three 15 min washes, membranes were visualized using ECL™ Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham Bioscience) and exposure to film (MR, Kodak, Rochester, NY). The density of bands was quantified by using an Imager Scanner II (Amersham Bioscience) and ImageQuant TL software (Amersham Bioscience) [19]. Band density among different blots was normalized according to the density of a reference sample. Band density was also normalized according to the β-actin content [3].

2.6. Glucose, insulin and IGF-1 analyses

Glucose was analyzed using the Infinity™ (ThermoTrace Ltd, Cat. # TR15498; Melbourne, Australia) colorimetric assay modified in the following manner; plasma was diluted 1:5 in dH2O, and 10 μL of diluted plasma was added to 300 μL reagent mix. All samples were run in triplicate. The intra-assay and inter-assay CVs are 3% and 5%, respectively and the sensitivity was 10 mg/dL.

Insulin was measured by RIA in accordance with manufacturer recommendations (Coat-A-Count Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA) and completed in a single array. When using ovine serum, the intra-assay CV is <3% and sensitivity was 0.05 ng/ml. IGF-1 was run on fetal serum samples using Immulite test kits on an Immulite 1000 (Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA) in a single array, the intra-assay CV is <5% and sensitivity was 20 ng/ml.

2.7. Statistics

Data were analyzed as a complete randomized design using GLM (General Linear Model of Statistical Analysis System) [20]. The authors considered each conceptus (fetus and placenta) to be the appropriate experimental unit in this study even though 2 fetuses may reside in the same uterus in the situation of twins. This is especially pertinent when we consider that twins can be composed of 2 females, two males or a male and a female fetus. Further, each fetus is attached to variable numbers of placentomes in the horn in which it resides. In a careful examination of the data, it was determined that there were no more similarities between 2 conceptuses residing in separate horns of the same uterus than between fetuses residing in different uteri of other ewes within the same group. Since there was no significant difference between sexes in any measurement taken, data of both sexes were combined for analysis. Mean separation was performed using LSMEANS. Means ± SEM were considered different when P < 0.05.

3. Results

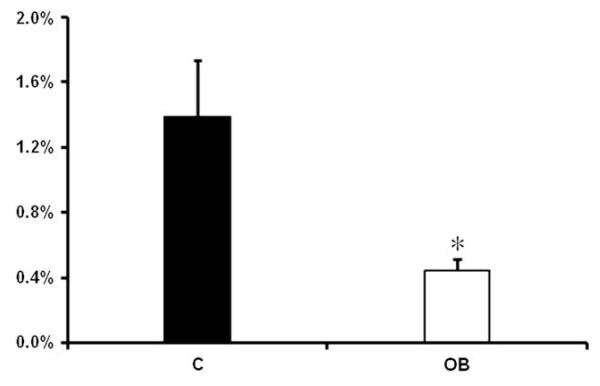

OB ewes increased (P < 0.05) their weight by approximately 48% from diet initiation to necropsy at day 75 (65 ± 2 kg and 96 ± 2 kg, respectively), while body weights of C ewes increased (P < 0.05) only approximately 8% over the same time period (64 ± 2 kg and 69 ± 2 kg, respectively). On day 75 of gestation, the body weight and empty carcass weight of OB fetuses were greater (P < 0.05) than that of C fetuses (Table 1). However, no differences were observed in total placentome weight or the total weight of CAR or COT tissues across dietary groups (Table 1). Further, neither placentome number nor average placentome weight of OB or C ewes differed (Table 1). At necropsy, plasma concentrations of glucose, insulin and IGF-1 were higher (P < 0.05) in the maternal and fetal blood streams from OB than C ewes (Table 2). Surprisingly, vascular density was observed to be lower (P < 0.05) in COT tissue of OB ewes compared to C ewes (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Fetal and placental measurements from C and OB ewes on day 75 of gestation.

| TRT | Fetal wt, g | Empty carcass wt, g | Total CAR wt, g | Total COT wt, g | Total plac. wt, g | Total plac. no | Avg. plac. wt, g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C (N = 10) | 185.72± 6.89 | 147.64 ±4.88 | 115.09 ± 9.76 | 541.85± 30.91 | 656.94 ±36.27 | 44.3± 2.7 | 15.04 ±0.83 |

| OB (N = 10) | 234.36 ± 6.61 | 166.34 ±2.97 | 108.93 ± 7.45 | 507.63± 33.82 | 616.55±36.57 | 46.7 ± 2.7 | 13.54±1.01 |

| P-value | * | * | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

Plac. = placentomes; and N = number of fetuses.

P< 0.05.

Table 2.

Fetal and maternal plasma glucose, insulin and IGF-1 concentration C and OB ewes on day 75 of gestation.

| Fetal plasma |

Maternal plasma |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | OB | P-value | C | OB | P-value | |

| Glucose (mg/dl) |

25.35±2.10 | 43.63 ± 5.58 | <0.05 | 52.12± 3.54 | 65.5 ± 6.67 | <0.05 |

| Insulin (IU/ml) |

1.14 ±0.35 | 7.29± 1.31 | <0.01 | 4.81 ± 1.60 | 25.01 ± 9.04 | <0.05 |

| IGF-1 (ng/ml) |

44.62 ±0.90 | 53.30 ± 1.76 | <0.05 | 38.36 ± 1.78 | 44.56 ± 2.29 | <0.05 |

Fig. 1.

Vascular area density of COT tissue on day 75 of gestation in C and OB ewes. Figure shows the mean ± SEM for the vascular area density of COT tissues from C and OB ewes. ■: control fed ewes; □: obese over-nourished ewes; mean ± SEM; and n = 10 in each group.

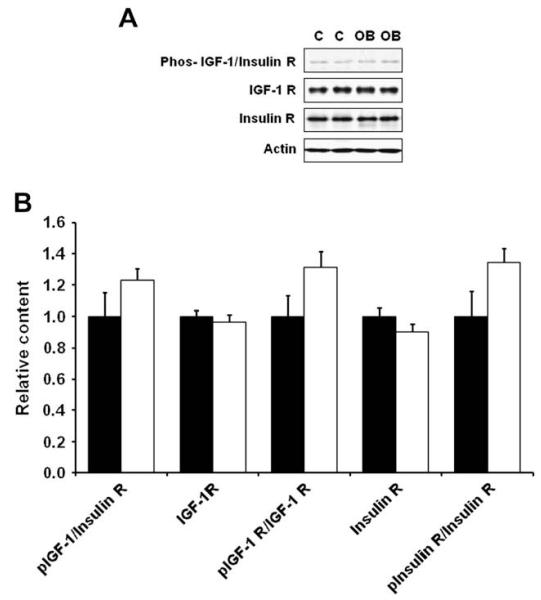

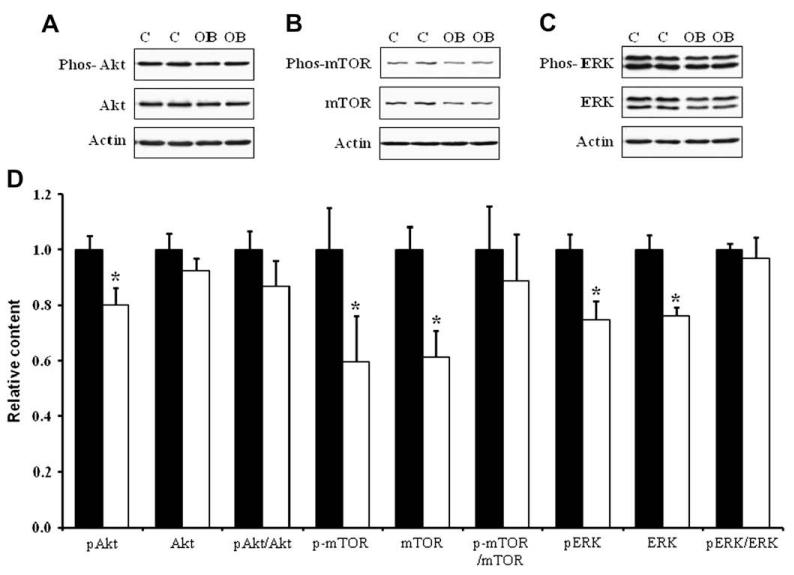

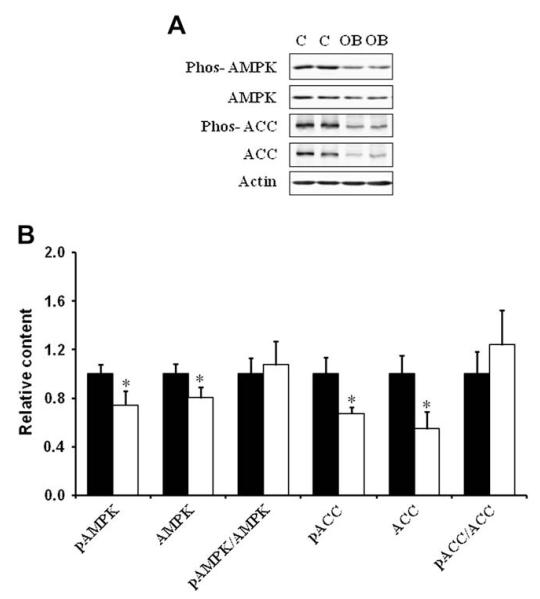

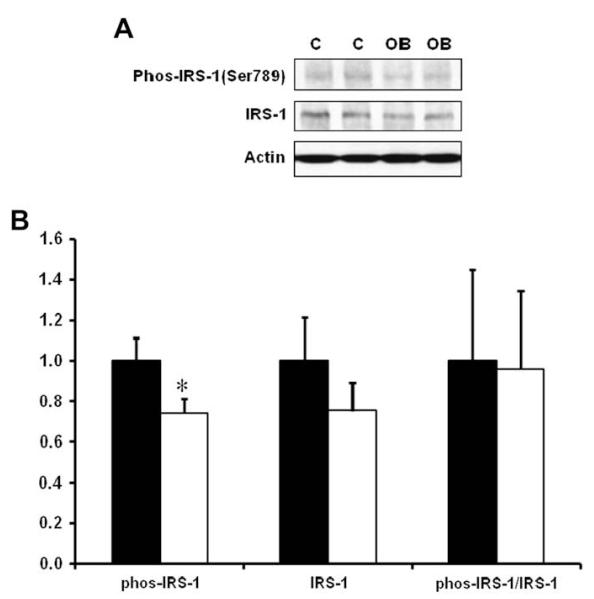

Western blotting analysis indicated that the content of total insulin receptor, total IGF-1 receptor and their phosphorylated form, phos-IGF-1 R (Tyr1131)/insulin R (Tyr 1146) in COT arterial tissues were similar across dietary groups (Fig. 2). There was, however, a reduction of the down-stream insulin signaling, as there were decreases in total mTOR and ERK1/2, and phosphorylated Akt, mTOR and ERK1/2 in COT arterial tissues of OB versus C ewes (P < 0.05; Fig. 3). Further, total AMPK and phosphorylated AMPK at Thr 172 (the active form) were reduced by 19.7 ± 8.4% (P < 0.05) and 25.9 ± 7.7% (P < 0.05) respectively in the COT arterial tissues of OB than C ewes (Fig. 4). Total acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), a down-stream target of AMPK, and its phosphorylated form were also reduced by 32.9 ± 9.2% (P < 0.05) and 45.4 ± 14.6% (P < 0.05) in the COT arterial tissue of OB versus C ewes, respectively (Fig. 4). Further, the phosphorylation of IRS-1 at Ser 789, a site phosphorylated by AMPK, was 24.5 ± 9.0% (P < 0.05) lower in COT arterial tissue of OB than C ewes (Fig. 5).

Fig. 2.

Phosphorylation of IGF-1/insulin receptors in COT arteries of day 75 of gestation in C and OB ewes. Panel A shows representative immunoblots of both phosphorylated IGF-1 and insulin receptors; Panel B shows statistical data. ■: control fed ewes; □: obese over-nourished ewes; mean ± SEM; and n = 10 in each group.

Fig. 3.

Total and phosphorylated Akt, mTOR, and ERK1/2 in COT arteries of day 75 of gestation in C and OB ewes. Panel A shows representative Akt and phospho-Akt immunoblots; Panel B shows representative mTOR and phospho-mTOR immunoblots; Panel C shows representative ERK1/2 and phospho-ERK1/2 immunoblots; and Panel D shows statistical data. ■: control fed ewes; □: obese over-nourished ewes; mean ± SEM; and n = 10 in each group.

Fig. 4.

Total and phosphorylated AMPK and ACC in COT arteries of day 75 of gestation in C and OB ewes. Panel A shows representative AMPK, ACC, phospho-AMPK and phospho-ACC immunoblots; and Panel B shows statistical data. ■: control fed ewes; □: obese over-nourished ewes; mean ± SEM; *: P < 0.05; and n = 10 in each group.

Fig. 5.

Total and phosphorylated IRS-1 (Ser 789) in COT arteries of day 75 of gestation in C and OB ewes. Panel A shows representative IRS-1 and phospho-IRS-1 immunoblots; Panel B shows statistical data. ■: control fed ewes; □: obese over-nourished ewes; mean ± SEM; and n = 10 in each group.

In the ewes allowed to lamb, OB ewes remained to be much higher weight than C ewes, similar to that observed on day 75 of gestation. Birth weights of lambs from both OB and C ewes were similar, averaging 6.00 ± 0.30 kg and 5.32 ± 0.47 kg, respectively. Interestingly, OB ewes had shorter (P < 0.05) gestation lengths than C ewes (OB versus C: 144.7 ± 0.7 versus 151.4 ± 0.5 days, P < 0.05).

4. Discussion

These data demonstrate that over-nutrition of ewes during early to midgestation was associated with a reduced vascularity of COT tissues of the placentome. This observation was consistent with our previous report showing that vascularity was increased in COT tissues of cows and ewes experienced maternal nutrient restricted during the first half of gestation [2,3]. Together, these data suggest that placental vascularity is negatively impacted by exposure to increasing levels of maternal nutrients. The reduction in COT vascular density in OB ewes in this study did not appear to be a result of increased nonvascular tissue growth, as there was no difference in average COT tissue weight across dietary group. The COT capillary beds grow primarily by branching angiogenesis over the last two-thirds of gestation in the sheep [21]. Consistent with the observed decrease in COT vascularity in this study, our laboratory recently reported that mRNA and protein levels of a group of potent placental angiogenic factors including VEGF, PLGF, FGF, angiopoietin 1 and 2, were markedly down-regulated in COT arteries of OB versus C ewes at midgestation (S.P. Ford, unpublished data). The decreased vascularity within the COT tissues of OB versus C ewes would be expected to reduce maternal to fetal nutrient transfer in OB versus C ewes. This is consistent with the observed lack of birth weight differences observed between OB and C ewes, even though significant fetal weight differences (OB > C) were observed at midgestation.

While it is expected that the reduced gestation lengths exhibited by OB ewes may have played a role in reducing lamb size at birth in this dietary group, recent observations in our laboratory (S.P. Ford, unpublished observations) demonstrated that fetal weights of OB and C ewes were similar as early as day 135 of gestation. While placental growth slows at midgestation in many mammalian species, placental transport capacity keeps pace with fetal growth throughout gestation in a variety of species [22]. Progressively increasing blood flow to the gravid uterus, and more specifically to the site of maternal: fetal nutrient exchange is vital for optimal fetal growth and development in all mammalian species studied to date [23]. Based on numerous studies, it appears that increased blood flow, rather than increased extraction of nutrient per ml of blood is the primary mechanism of increased transplacental exchange throughout gestation [24]. Based on these data, it would appear that adequate blood flow to the placenta is critical for normal fetal growth. In support of this concept, conditions associated with reduced rates of fetal and placental growth (e.g., maternal genotype, increased fetal numbers, environmental heat stress) are associated with reduced placental blood flows and reduced fetal oxygen and nutrient uptakes [25].

To investigate the underlying mechanism(s) associated with this reduced vascularity under our over-nutrient regimen, two key pathways associated with cell growth, proliferation and angiogenesis were evaluated in COT arteries of ewe placentomes. The phosphorylation of both Akt and ERK1/2, key intermediates in the PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways respectively, was decreased in day 75 COT arteries of OB versus C ewes. In contrast, previous reports from our laboratory demonstrated that PI3K/Akt and MAPK (ERK1/2) were up-regulated in placentomal arteries under nutrient deficiency [2,3]. The PI3K/Akt pathway promotes endothelial cell survival and protein synthesis [26,27], migration and capillary-like structure formation [28] and its down-regulation in COT arteries is expected to reduce angiogenesis. The PI3K/Akt pathway has also been previously reported to be important for placental growth [29]. The placenta of Akt knockout mice display significant hypotrophy and decreased vascularization [29]. The MAPK pathway is mainly involved in cell mitogenesis and very recently, MAPK/ERK1/2 has been shown to mediate the mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway and thus links to the control of protein synthesis [30]. ERK1/2 was also reported to be crucial for endothelial cell proliferation in sheep and human placental arteries during NO-mediated angiogenesis [31]. Similar to Akt, we found that ERK1/2 and its phosphorylated activated form were down-regulated in COT arteries of OB ewes compared to C ewes (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the reduction in Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation was mainly due to the reduction in total Akt and ERK1/2 content, which is consistent with the long-term effect of cell signaling pathways on gene expression. Cells change the level of phosphorylation as an acute response but change protein expression when subjected to long-term stimuli such as obesity.

Since both Akt and ERK1/2 signaling are down-stream events of insulin/IGF-1 signaling, we further investigated the upstream mediators of insulin/IGF-1 signaling in the COT arteries. Insulin stimulation of placental cells enhanced the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Akt by 286 ± 23% and 393 ± 17%, hinting the important role of insulin in placental development and, very possibly, angiogenesis [32]. Insulin exerts its biological effects mainly through activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway [5-10]. The binding of insulin to its receptor activates the receptor tyrosine kinase activity, leading to phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1). Phosphorylated IRS-1 serves as a docking center for recruitment and activation of down-stream pathways [33], including PI3K/Akt pathway [6,7,11,12] and MAPK (ERK1/2) pathway [13,14]. Thus, IRS-1 is a key site mediating insulin signaling [33].

AMPK is a heterotrimeric enzyme with α, β, and γ subunits [34,35]. AMPK is switched on by an increase in the AMP/ATP ratio, which leads to the phosphorylation of AMPK at Thr 172 by AMPK kinases [34,36,37]. Once activated, AMPK promotes glucose uptake and inhibits lipid synthesis in cells [38,39]. Activated AMPK phosphorylates IRS-1 at Ser 789 which enhances insulin signaling [15]. Thus, AMPK is a target for the prevention of type II diabetes [40]. Metformin, a common drug used to treat type II diabetes, exerts its anti-diabetic effect through activation of AMPK [41,42]. We observed a reduction in the phosphorylation of AMPK and its down-stream effector, ACC at Ser 79. Since ACC phosphorylation at Ser 79 was exclusively catalyzed by AMPK, phosphorylation of AMPK at Thr 172 coupling with ACC phosphorylation at Ser 79 was commonly used to measure AMPK activity. These data showed that AMPK activity was reduced in the COT arteries of OB ewes. This reduction was accompanied by a reduction in IRS-1 phosphorylation at Ser 789, a site phosphorylated by AMPK. To be a phosphorylation site beneficial to IRS-1 mediated signaling, this reduction in IRS-1 phosphorylation mitigates down-stream insulin/IGF-1 signaling, including Akt/mTOR and MAPK(ERK1/2) signaling. This notion is consistent with several very recent reports showing that AMPK inhibition was associated with insulin resistance in skeletal muscle [43-45].

Most previous studies regarding angiogenesis in the ovine placentome were focused on growth factors [46-48]. In the present study, despite the augmented insulin and IGF-1 levels in the fetal blood stream of OB mother, the Akt and ERK 1/2 signaling were down-regulated in OB COT arteries. These data suggest that in addition to growth factors, intracellular signaling events may be equally important in mediating angiogenesis in arteries.

5. Conclusion

These data show that the phosphorylation of AMPK and its down-stream target ACC was reduced in COT arterial tissue of OB mothers. This reduction in AMPK activity decreased the phosphorylation of IRS-1 at Ser 789, which is expected to reduce the PI3K activation mediated by IRS-1, mitigating down-stream insulin/IGF-1 signaling in OB ewes despite increased plasma glucose, insulin and IGF-1 concentrations. The mitigation of insulin/IGF-1 down-stream signaling in COT arteries was associated with a reduced vascular density in COT tissue.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Myrna Miller and Mr. Ryan Gustafson for assistance with animal care and tissue collection. This project was supported by University of Wyoming INBRE P20 RR016474-04 and by National Research Initiative Competitive Grant no. 2008-35203-19084 from the USDA Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service.

References

- [1].Ford SP. Cotyledonary placenta. In: Knobil E, Neil JD, editors. Encyclopedia of reproduction. Vol. 1. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. pp. R730–8. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zhu MJ, Du M, Hess BW, Nathanielsz PW, Ford SP. Periconceptional nutrient restriction in the ewe alters MAPK/ERK1/2 and PI3K/Akt growth signaling pathways and vascularity in the placentome. Placenta. 2007;28:R1192–9. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zhu MJ, Du M, Hess BW, Means WJ, Nathanielsz PW, Ford SP. Maternal nutrient restriction upregulates growth signaling pathways in the cotyledonary artery of cow placentomes. Placenta. 2007;28:R361–8. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Reynolds LP, Redmer DA. Angiogenesis in the placenta. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:1033–40. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.4.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Subramaniam S, Shahani N, Strelau J, Laliberte C, Brandt R, Kaplan D, et al. Insulin-like growth factor 1 inhibits extracellular signal-regulated kinase to promote neuronal survival via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase A/c-Raf pathway. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2838–52. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5060-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bush JA, Kimball SR, O’Connor PM, Suryawan A, Orellana RA, Nguyen HV, et al. Translational control of protein synthesis in muscle and liver of growth hormone-treated pigs. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1273–83. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Vary TC. IGF-I stimulates protein synthesis in skeletal muscle through multiple signaling pathways during sepsis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R313–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00333.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Park IH, Erbay E, Nuzzi P, Chen J. Skeletal myocyte hypertrophy requires mTOR kinase activity and S6K1. Exp Cell Res. 2005;309:211–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Song YH, Godard M, Li Y, Richmond SR, Rosenthal N, Delafontaine P. Insulin-like growth factor I-mediated skeletal muscle hypertrophy is characterized by increased mTOR–p70S6K signaling without increased Akt phosphorylation. J Investig Med. 2005;53:135–42. doi: 10.2310/6650.2005.00309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Latres E, Amini AR, Amini AA, Griffiths J, Martin FJ, Wei Y, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) inversely regulates atrophy-induced genes via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/Akt/mTOR) pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2737–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407517200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Anthony JC, Anthony TG, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. Signaling pathways involved in translational control of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle by leucine. J Nutr. 2001;131:856S–60S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.856S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chiang GG, Abraham RT. Phosphorylation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) at Ser-2448 is mediated by p70S6 kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25485–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501707200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hwang JJ, Hur KC. Insulin cannot activate extracellular-signal-related kinase due to inability to generate reactive oxygen species in SK-N-BE(2) human neuroblastoma cells. Mol Cells. 2005;20:280–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Choi WS, Sung CK. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase enhances insulin stimulation of insulin receptor substrate 1 tyrosine phosphorylation and extracellular signal-regulated kinases in mouse R-fibroblasts. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2004;24:67–83. doi: 10.1081/rrs-120034229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Jakobsen SN, Hardie DG, Morrice N, Tornqvist HE. 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylates IRS-1 on Ser-789 in mouse C2C12 myotubes in response to 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46912–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ford SP, Hess BW, Schwope MM, Nijland MJ, Gilbert JS, Vonnahme KA, et al. Maternal undernutrition during early to mid-gestation in the ewe results in altered growth, adiposity, and glucose tolerance in male offspring. J Anim Sci. 2007;85:1285–94. doi: 10.2527/jas.2005-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vonnahme KA, Hess BW, Nijland MJ, Nathanielsz PW, Ford SP. Placentomal differentiation may compensate for maternal nutrient restriction in ewes adapted to harsh range conditions. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:3451–9. doi: 10.2527/jas.2006-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vonnahme KA, Hess BW, Hansen TR, McCormick RJ, Rule DC, Moss GE, et al. Maternal undernutrition from early- to mid-gestation leads to growth retardation, cardiac ventricular hypertrophy, and increased liver weight in the fetal sheep. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:133–40. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.012120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhu MJ, Ford SP, Nathanielsz PW, Du M. Effect of maternal nutrient restriction in sheep on the development of fetal skeletal muscle. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:1968–73. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.034561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].SAS . SAS user’s guide. Version 8. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Reynolds LP, Borowicz PP, Vonnahme KA, Johnson ML, Grazul-Bilska AT, Redmer DA, et al. Placental angiogenesis in sheep models of compromised pregnancy. J Physiol. 2005;565:43–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.081745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Reynolds LP, Redmer DA. Utero-placental vascular development and placental function. J Anim Sci. 1995;73:1839–51. doi: 10.2527/1995.7361839x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ford SP, Christenson LK, Rosazza JP, Short RE. Effects of Ponderosa pine needle ingestion of uterine vascular function in late-gestation beef cows. J Anim Sci. 1992;70:1609–14. doi: 10.2527/1992.7051609x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Reynolds LP, Ferrell CL, Ford SP. Transplacental diffusion and blood flow of gravid bovine uterus. Am J Physiol. 1985;249:R539–43. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1985.249.5.R539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Regnault TR, Hay JrWW. In vivo techniques for studying fetoplacental nutrient uptake, metabolism, and transport. Methods Mol Med. 2006;122:207–24. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-989-3:205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gerber HP, McMurtrey A, Kowalski J, Yan M, Keyt BA, Dixit V, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates endothelial cell survival through the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/Akt signal transduction pathway. Requirement for Flk-1/KDR activation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30336–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Fujio Y, Walsh K. Akt mediates cytoprotection of endothelial cells by vascular endothelial growth factor in an anchorage-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16349–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Shiojima I, Walsh K. Role of Akt signaling in vascular homeostasis and angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2002;90:1243–50. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000022200.71892.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yang ZZ, Tschopp O, Hemmings-Mieszczak M, Feng J, Brodbeck D, Perentes E, et al. Protein kinase B alpha/Akt1 regulates placental development and fetal growth. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32124–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ma L, Chen Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Pandolfi PP. Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:179–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zheng J, Wen Y, Austin JL, Chen DB. Exogenous nitric oxide stimulates cell proliferation via activation of a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in ovine fetoplacental artery endothelial cells. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:375–82. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.043190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Boileau P, Cauzac M, Pereira MA, Girard J, Hauguel-De Mouzon S. Dissociation between insulin-mediated signaling pathways and biological effects in placental cells: role of protein kinase B and MAPK phosphorylation. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3974–9. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.9.8391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Shao J, Yamashita H, Qiao L, Draznin B, Friedman JE. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase redistribution is associated with skeletal muscle insulin resistance in gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2002;51:19–29. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kim J, Solis RS, Arias EB, Cartee GD. Postcontraction insulin sensitivity: relationship with contraction protocol, glycogen concentration, and 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:575–83. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00909.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: a key system mediating metabolic responses to exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:28–34. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000106171.38299.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hawley SA, Pan DA, Mustard KJ, Ross L, Bain J, Edelman AM, et al. Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta is an alternative upstream kinase for AMP-activated protein kinase. Cell Metab. 2005;2:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Woods A, Dickerson K, Heath R, Hong SP, Momcilovic M, Johnstone SR, et al. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta acts upstream of AMP-activated protein kinase in mammalian cells. Cell Metab. 2005;2:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hardie DG, Hawley SA. AMP-activated protein kinase: the energy charge hypothesis revisited. Bioessays. 2001;23:1112–9. doi: 10.1002/bies.10009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Fujii N, Jessen N, Goodyear LJ. AMP-activated protein kinase and the regulation of glucose transport. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E867–877. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00207.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Musi N, Goodyear LJ. Targeting the AMP-activated protein kinase for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord. 2002;2:119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zang M, Zuccollo A, Hou X, Nagata D, Walsh K, Herscovitz H, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase is required for the lipid-lowering effect of metformin in insulin-resistant human HepG2 cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:R47898–905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Musi N, Hirshman MF, Nygren J, Svanfeldt M, Bavenholm P, Rooyackers O, et al. Metformin increases AMP-activated protein kinase activity in skeletal muscle of subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:R2074–81. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.7.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Steinberg GR, Michell BJ, van Denderen BJ, Watt MJ, Carey AL, Fam BC, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced skeletal muscle insulin resistance involves suppression of AMP-kinase signaling. Cell Metab. 2006;4:465–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lee YS, Kim WS, Kim KH, Yoon MJ, Cho HJ, Shen Y, et al. Berberine, a natural plant product, activates AMP-activated protein kinase with beneficial metabolic effects in diabetic and insulin-resistant states. Diabetes. 2006;55:2256–64. doi: 10.2337/db06-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Watt MJ, Dzamko N, Thomas WG, Rose-John S, Ernst M, Carling D, et al. CNTF reverses obesity-induced insulin resistance by activating skeletal muscle AMPK. Nat Med. 2006;12:541–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Babischkin JS, Suresch DL, Pepe GJ, Albrecht ED. Differential expression of placental villous angiopoietin-1 and -2 during early, mid and late baboon pregnancy. Placenta. 2007;28:212–8. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Pfarrer CD, Ruziwa SD, Winther H, Callesen H, Leiser R, Schams D, et al. Localization of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 in bovine placentomes from implantation until term. Placenta. 2006;27:889–98. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Reynolds LP, Borowicz PP, Vonnahme KA, Johnson ML, Grazul-Bilska AT, Wallace JM, et al. Animal models of placental angiogenesis. Placenta. 2005;26:689–708. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]